Abstract

Background

Genome-wide association studies have revealed a link between essential tremor (ET) and the gene SLC1A2, which encodes excitatory amino acid transporter type 2 (EAAT2). We explored EAAT biology in ET by quantifying EAAT2 and EAAT1 levels in the cerebellar dentate nucleus, and expanded our prior analysis of EAAT2 levels in the cerebellar cortex.

Objective

To quantify EAAT2 and EAAT1 levels in the cerebellar dentate nucleus and cerebellar cortex of ET cases vs. controls.

Methods

We used immunohistochemistry to quantify EAAT2 and EAAT1 levels in the dentate nucleus of a discovery cohort of 16 ET cases and 16 controls. Furthermore, we quantified EAAT2 levels in the dentate nucleus in a replicate cohort (61 ET cases, 25 controls). Cortical EAAT2 levels in all 77 ET cases and 41 controls were quantified.

Results

In the discovery cohort, dentate EAAT2 levels were 1.5-fold higher in 16 ET cases vs. 16 controls (p = 0.007), but EAAT1 levels did not differ significantly (p = 0.279). Dentate EAAT2 levels were 1.3-fold higher in 61 ET cases vs. 25 controls in the replicate cohort (p = 0.022). Cerebellar cortical EAAT2 levels were 20% and 40% lower in ET cases vs. controls in the discovery and the replicate cohorts (respective p values = 0.045 and < 0.001).

Conclusion

EAAT2 expression is enhanced in the ET dentate nucleus, in contrast to differentially reduced EAAT2 levels in the ET cerebellar cortex, which might reflect a compensatory mechanism to maintain excitation-inhibition balance in cerebellar nuclei.

Keywords: Essential tremor, Cerebellum, Neurodegenerative, GFAP, EAAT2, Excitotoxicitiy

1. Introduction

Essential tremor (ET) is one of the most common neurological disorders; disease prevalence increases with advancing age, reaching values in excess of 20% among persons in their 90s [1]. A growing body of clinical, physiological and postmortem evidence now links it with an abnormal cerebellum [2]. Indeed, a number of postmortem features distinguish ET from similarly-aged control brains, including (1) increased numbers of torpedoes and related Purkinje cell (PC) axonal pathologies [3,4], (2) increased heterotopic displacement of PCs [5], (3) abnormal climbing fiber (CF)-PC connections [6,7], and (4) a dense and elongated basket cell plexus surrounding the PCs [8,9]. In addition, there is a loss of PCs in several [3,10] although not all studies [11,12].

A polymorphism in the gene solute carrier family 1, member 2 (SLC1A2) has recently been associated in many [13–15] although not all studies with ET [16]. Hence, the biological links between SLC1A2 and ET are of significant current interest. The SLC1A2 gene encodes excitatory amino acid transporter 2 (EAAT2), which belongs to a family of excitatory amino-acid transporters (EAATs) [17]. Astrocytes express both EAAT1 and EAAT2, and these transporters regulate extracellular glutamate levels in the brain. Excessive excitatory neurotransmission has been postulated as a mechanism for tremor in animal models of tremor, although there is no empiric evidence that this occurs in ET [18]. We previously reported that the levels of EAAT2, but not EAAT1, were reduced in the cerebellar cortex in 16 ET cases vs. 13 controls [19]. In theory, this reduction could be associated with a decreased capacity of astrocytes to clear extracellular glutamate, thereby enhancing the vulnerability of PCs to excitotoxic injury.

Aside from the cerebellar cortex, another brain region implicated in ET is the dentate nucleus. Structural and functional changes of the dentate nucleus in ET have been reported in imaging studies [20]. The dentate nucleus receives strong inhibitory input from PCs, which provide the sole neuronal output from the cerebellar cortex; it also receives excitatory inputs from collateral branches of mossy fibers and CF collaterals [21]. Long-standing rhythmic firing of CF excitatory inputs on PCs and, to a lesser degree, on dentate nuclei via CF collaterals, has been postulated as a pathogenic mechanism in animal models of tremor [22]. In vivo analyses in animal studies have demonstrated that intrinsic firing rates of cerebellar nuclear cells are modulated during movements [21], with effectiveness of inhibitory versus excitatory inputs varying during specific motor behaviors. Therefore, the proper timing of excitatory neurotransmission regulated by EAATs in the dentate nucleus could be important in ET. Extending our previous study [19], we now assess the expression levels of EAAT2 and EAAT1 in the dentate nucleus of ET cases vs. controls, and significantly expand and replicate our analysis of EAAT2 in the cerebellar cortex in a far larger cohort of ET cases and controls.

2. Methods

2.1. Brain repository and study subjects

All ET brains were from the Essential Tremor Centralized Brain Repository (ETCBR), New York Brain Bank (NYBB), Columbia University, New York. The clinical diagnosis of ET was initially assigned by treating neurologists. Cases were assessed by a series of semi-structured clinical questionnaires, including Archimedes spirals and the information regarding family history and tremor characteristics. Finally, the diagnosis of ET was confirmed by an ETCBR study neurologist (EDL) using medical records, a detailed, videotaped, neurological assessment, and ETCBR diagnostic criteria [3]. The severity of tremor was rated using the total tremor score, based on the severity of postural and kinetic arm tremors (range = 0–36).

Most of the control brains were obtained from the NYBB (n = 28, 10 in the discovery cohort and 18 in the replicate cohort) and were from individuals followed at the Alzheimer disease (AD) Research Center or the Washington Heights Inwood Columbia Aging Project at Columbia University. They were followed prospectively with serial neurological examinations, and were clinically free of AD, ET, Parkinson's disease (PD), Lewy body dementia, or progressive supranuclear palsy. Thirteen controls were from the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center (McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA) (6 in the discovery cohort and 7 in the replicate cohort). EAAT2 immunostaining intensity in the cerebellar cortex of 8 of the current controls and 10 of the current ET cases was reported previously [19].

All study subjects signed informed consent approved by these University Ethics Boards. We performed a power analysis, using data collected in our prior study of cerebellar cortical EAAT2 levels by immunohistochemistry [19]. We found that, with the sample size of 13 in each group, we had a power of 0.90 to detect case-control differences of the magnitude detected previously. To be conservative, we chose 16. We chose controls who had available paraffin-embedded sections of the dentate nucleus and were >70 years old at the time of death, thereby allowing us to frequency-match them to ET cases by age at death. For our replicate cohort, we identified all of the remaining ET cases and controls in the brain bank with available dentate nucleus in paraffin-embedded sections; there were 61 such ET cases and 25 controls.

2.2. Neuropathological assessment

All ET and control brains had a complete neuropathological assessment at the NYBB and Harvard Brain Bank, as described previously [2]. The postmortem interval (PMI), the time from death to the time of brain placed in −80 °C, in each case was recorded. We did not include ET cases with Lewy body pathology (α-synuclein staining) or dentate nucleus degeneration [2].

A standard 3 × 20 × 25 mm parasagittal neocerebellar block, including dentate nucleus, was obtained from a 0.3-cm-thick parasagittal slice located 1 cm from the cerebellar midline. Paraffin sections (7 μm thick) were stained with Luxol fast blue hematoxylin and eosin (LH&E), and PC counts and torpedo counts were quantified as described previously [2].

2.3. Dentate nucleus immunohistochemistry

Seven-μm-thick paraffin-embedded cerebellar sections were incubated with guinea pig anti-EAAT2 antibody (Millipore, ab1783, 1:200) or mouse anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody (Sigma, G3893, 1:100) at 4 °C for 24 h after antigen retrieval in Trilogy (Cell Marque) for 60 min, 100 °C. The sections were incubated with goat anti-mouse (Fisher Scientific, 1:200) or anti-guinea pig IgG biotin-conjugated secondary antibody (Millipore, 1:200), respectively, followed by 3,3′ -diaminobenzidine (DAB) precipitation. These antibodies have been validated previously [19].

Whole slide scanning was performed with a 20× lens (Leica SCN400 scanner) and a trained and clinically-blinded technician (GCK) traced the outline of the dentate nucleus and measured the average intensity of EAATs immunoreactivity/μm2 of dentate area with Leica Biosystems Tissue IA Software, version 2.0. EAAT2 immunoreactivity was similarly quantified in the cerebellar cortex, as previously described [19]. The EAAT immunoreactivity was normalized to controls, for which EAAT immunoreactivity was set to be 1.00.

GFAP immunohistochemistry was used to assess whether increased astrocytes in the dentate nucleus could account for increases in EAAT2 levels. Due to the lack of a distinctive border between white matter and the dentate nucleus in many cases and dense astrocyte processes normally present in white matter, the GFAP immunostained sections were not suitable for quantitative image analysis as performed for EAAT proteins. Therefore, we developed a semi-quantitative GFAP rating scale. A senior neuropathologist (PLF), blinded to clinical information, evaluated the GFAP-positive process and cell body densities in the dentate nucleus in each ET case and control. The following semi-quantitative scale was used: 1 (few discernible processes, paler overall staining than adjacent white matter); 2 (mild to moderate processes, rare to sparse cell body staining); 3 (moderate number of processes, mild cell body staining), 4 (dense processes and moderate to severe cell body staining). For each ET case and control, eight microscopic images (4 each at 50× and 100 × magnification) were acquired in randomly selected areas spanning the dentate nucleus, and each image was assigned a 1–4 rating.

For dual immunofluorescence studies, we immunostained paraffin-embedded sections with anti-EAAT2 antibodies and mouse anti-glutamine synthetase (BD Transduction, 610518, 1:300) or mouse anti-GFAP. The secondary antibodies were goat anti-guinea pig antibodies conjugated with Alexa fluorophore 488 or goat anti-mouse antibodies conjugated with Alexa fluorophore 594 (All Invitrogen, 1:100).

2.4. Genotyping of rs3794087

We obtained genomic DNA from frozen human brain tissue in 69 available ET cases and 24 controls using QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen) and we amplified the genetic fragment containing rs3794087, an intronic variant of SLC1A2, by polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) as previously described [15]. We sent the PCR fragments for commercial sequencing for the genotype of rs3794087.

2.5. Data analyses

Data were analyzed in Prism (v6.0a) and SPSS (v22). Demographic and clinical characteristics of ET cases and controls were compared using Student's t–tests, chi-square tests, or Fisher's exact tests. All the continuous measures were tested for normal distributions (Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests). For the normally distributed continuous measures, we used Student t-tests. For non-normally distributed continuous measures, we used Mann-Whitney U tests. Pearson's correlation coefficients were used to assess correlations between normally-distributed variables. For the non-normally distributed variables, we assessed the correlations using Spearman's rank correlation coefficients. In two different linear regression models, we assessed whether cerebellar cortical EAAT2 levels and dentate EAAT2 levels differed by diagnosis, after adjusting for torpedo count and PC count.

3. Results

The 16 ET cases and 16 controls in the discovery cohort did not differ to a significant degree by age, gender, brain weight, Braak AD score, or Consortium to Establish a Registry for AD (CERAD) plaque score (Table 1). ET cases had a longer PMI than controls. Consistent with our previous studies, ET cases had a lower PC count and a higher torpedo count (marginally) than controls.

Table 1.

Clinical and pathological features of controls and essential tremor cases in the discovery and replicate cohorts.

| Discovery cohort | p-value | Replicate cohort | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Controls | Essential tremor cases | Controls | Essential tremor cases | |||

| n | 16 | 16 | 25 | 61 | ||

| Age at death (years) | 82.5 ± 6.8 | 83.7 ± 7.4 | 0.638a | 67.2 ± 22.7 Median = 73.0 | 88.8 ± 5.9 Median = 90.0 | <0.001b |

| Gender | 0.716c | <0.001c | ||||

| Men | 7 (43.8%) | 5 (31.2%) | 20 (80.0%) | 22 (36.1%) | ||

| Women | 9 (56.2%) | 11 (68.8%) | 5 (20.0%) | 39 (63.9%) | ||

| Age of tremor onset (years) | NA | 32.5 ± 23.5 | NA | NA | 47.9 ± 20.6 Median = 55.0 | NA |

| Disease duration (years) | NA | 50.9 ± 23.4 | NA | NA | 40.8 ± 21.1 Median = 35.0 | NA |

| Total tremor score | NA | 24.0 ± 5.8 | NA | NA | 24.3 ± 6.6 | NA |

| Brain weight (grams) | 1190 ± 153 | 1214 ± 180 | 0.690 a | 1310 ± 178 | 1187 ± 124 | <0.001a |

| Postmortem interval (frozen, hours) | 18.4 ± 10.4 | 28.3 ± 8.1 | 0.005a | 20.3 ± 11.7 | 27.7 ± 12.5 | 0.019a |

| Braak AD score | 1.6 ± 1.0 Median = 2.0 | 2.1 ± 1.3 Median = 1.5 | 0.539b | 1.2 ± 1.4 Median = 1.0 | 2.4 ± 1.2 Median = 2.0 | <0.001b |

| CERAD plaque score d | 0.880c | 0.002c | ||||

| 0 | 6 (60.0%) | 10 (62.5%) | 16 (84.2%) | 20 (33.9%) | ||

| A | 4 (40.0%) | 4 (25.0%) | 1 (5.3%) | 18 (30.5%) | ||

| B | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (6.2%) | 2 (10.5%) | 15 (25.4%) | ||

| C | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (6.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (10.2%) | ||

| Purkinje cell counts | 11.2 ± 1.6 Median = 11.6 | 8.6 ± 1.8 Median = 8.6 | <0.001b | 11.4 ± 2.9 | 8.8 ± 1.5 | <0.001 a |

| Torpedo counts | 6.8 ± 9.2 Median = 3.0 | 12.9 ± 13.4 Median = 6.0 | 0.102b | 5.0 ± 3.9 Median = 4.0 | 16.5 ± 13.8 Median = 13.0 | <0.001 b |

| Dentate EAAT1 levels | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.279a | |||

| Dentate EAAT2 levels | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 0.007a | 1.0 ± 0.6 Median = 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.8 Median = 1.1 | 0.022b |

| Cerebellar cortical EAAT2 levels | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.045a | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | <0.001a |

| Dentate GFAP score | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 2.6 ± 1.0 | 0.668a | |||

Values represent mean ± standard deviation or number (percentage), and for variables that are not normally distributed, and the median is reported as well.

All the continuous measures were tested for normal distributions (Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests). For the normally distributed continuous measures, we used Student t-tests.

For non-normally distributed continuous measures, we used Mann-Whitney U tests.

Mean number of Purkinje cells (PCs) per 100× microscopic field, among 15 sampled fields.

NA = not applicable.

Values in bold are statistically significant.

Independent samples t-test.

Independent samples Mann-Whitney U test.

Chi-square test.

CERAD plaque scores of 6 controls in the discovery cohort and 12 controls and 11 ET cases in the replicate cohort were not available.

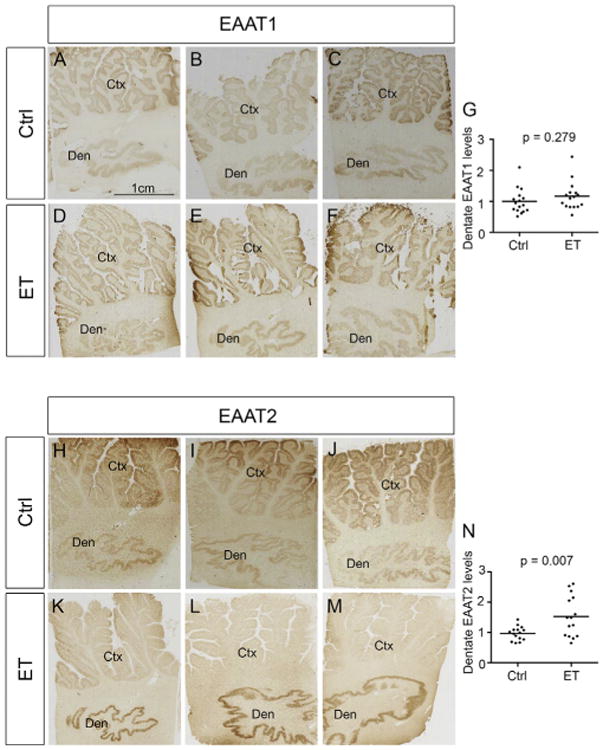

In the discovery cohort, dentate EAAT1 levels were similar between ET cases and controls (1.2 ± 0.5 vs. 1.0 ± 0.4, p = 0.279) whereas dentate EAAT2 levels were 50% higher in ET cases vs. controls (1.5 ± 0.6 vs. 1.0 ± 0.2, p = 0.007) (Fig. 1). Dentate EAAT1 and EAAT2 levels did not correlate with age of death, brain weight, Braak AD score or CERAD plaque score in either the ET group or the control group, nor did they differ by gender (discovery cohort, all p values > 0.05). Cases and controls did not differ with respect to age at death, brain weight, Braak AD score, CERAD plaque score or gender either. Hence, these five variables could not have been confounding factors in the observed case-control difference in the dentate EAAT2 levels. While PMI did differ in cases vs. controls, it did not correlate with EAAT2 levels (p value > 0.05), indicating that it was not a confounding factor either. We further found that cerebellar cortical EAAT2 levels were decreased by 20% in ET cases vs. controls (0.8 ± 0.2 vs. 1.0 ± 0.2, p = 0.045) (Table 1), consistent with our previous study [19].

Fig. 1.

Increased EAAT2 immunoreactivity in the ET dentate nucleus in the discovery cohort. Paraffin-embedded sections immunolabeled with anti-EAAT1 or anti-EAAT2 antibodies were digitally scanned and the intensity of immunostaining in the dentate nucleus was quantified by tissue image analysis software. EAAT1 levels in ET cases were similar to those in controls (immunostains from 3 ET cases and 3 controls are shown, A - F) whereas EAAT2 levels in ET cases were higher than those in controls (immunostains from 3 ET cases and 3 controls are shown, H - M). Quantification of dentate EAAT1 and EAAT2 levels are shown (G, N). Ctx: cerebellar cortex, Den: dentate nucleus. Ctrl: controls, ET: essential tremor.

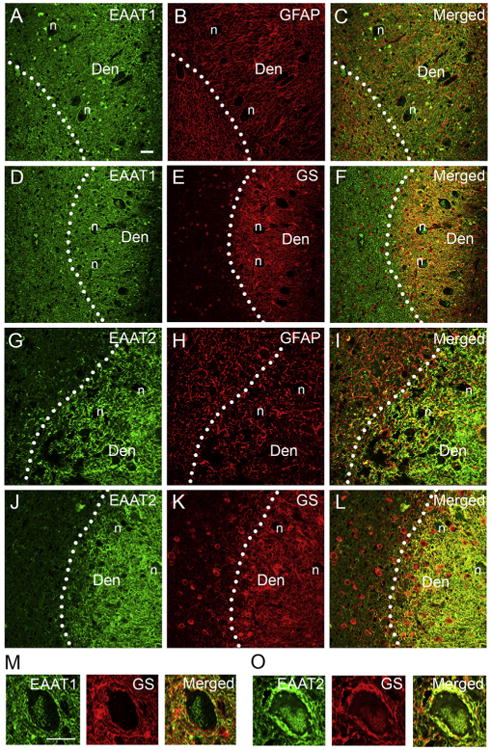

EAATs in the dentate nucleus partially colocalized with astrocytic markers, GFAP and glutamine synthetase, consistent with previous reports that GFAP and glutamine synthetase are expressed predominantly in the cell bodies and proximal processes of astrocytes whereas EAATs are expressed in the end feet of the astrocytic processes (Fig. 2A-L) [19,23]. In addition, there was a dense rim of astrocytic processes surrounding dentate neurons expressing predominantly EAAT2, which colocalized with glutamine synthetase (Fig. 2M,O). These results indicate that the enhanced EAAT2 expression in ET is predominantly in astrocytes in the dentate nucleus.

Fig. 2.

EAATs partially colocalize with astrocytic markers. Dual immunofluorescence labeling of ET dentate nucleus with anti-EAAT1 or anti-EAAT2 (Alexa 488, green, A, D, G, J), anti-GFAP (Alexa 594, red, B, H), and anti-glutamate synthetase (GS) (Alexa 594, red, E, K). Both EAAT1 and EAAT2 partially colocalized with GFAP or GS in the dentate nucleus (C, F, I, L). EAAT1 and EAAT2 was also expressed in the astrocytic processes surrounding dentate neuronal bodies, but EAAT2 was the predominant transporter in these regions (M, O). Den: dentate nucleus, n: dentate neuron cell body. Scale bar: 10 μm.

We used GFAP immunostaining and a semi-quantitative GFAP rating scale in the dentate nucleus to investigate whether ET cases had a general up-regulation of astrocytic markers. Supplemental Fig. 1A-D illustrates examples of semi-quantitative GFAP rating scores (range 1–4) for the determination of GFAP-positive astrocytic process and cell body densities. We found that ET cases and controls had similar dentate GFAP rating scores (2.6 ± 1. 0 vs. 2.4 ± 0.9, p = 0.668) (Supplemental Fig. 1E). Dentate GFAP rating scores did not correlate with either dentate EAAT1 or EAAT2 levels (EAAT1: Spearman's r = 0.156, p = 0.394; EAAT2: r = 0.253, p = 0.162). These data suggest a selective up-regulation of EAAT2 in the ET dentate nucleus.

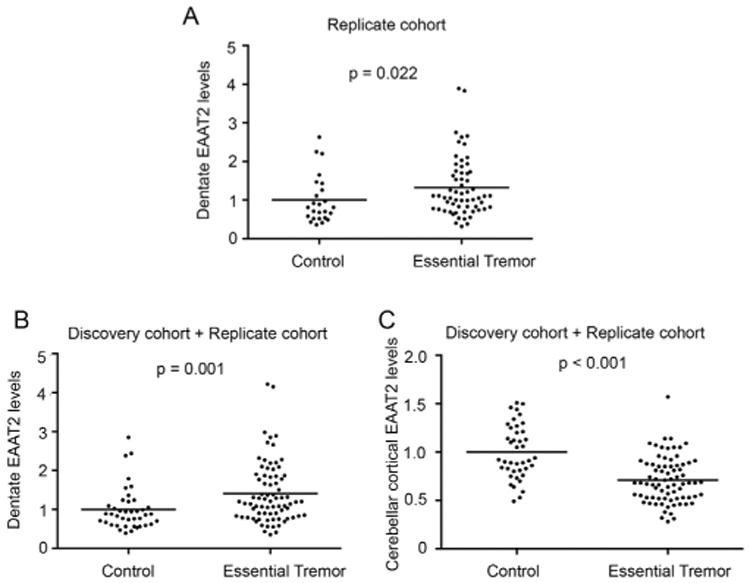

We further studied dentate EAAT2 levels in a replicate cohort of 25 controls and 61 ET cases. In this cohort, ET cases had an older age at death than controls, and more were women. As expected, ET cases had a lower brain weight, a longer PMI, a higher Braak AD stage, a higher CERAD score, a lower PC count, and a higher torpedo count (Table 1). In this replicate cohort, ET cases had 30% higher dentate EAAT2 levels vs. controls (1.3 ± 0.8 vs. 1.0 ± 0.6, p = 0.022) (Fig. 3A). Despite the presence of case-control differences in several variables in the replicate cohort (e.g., age, gender, brain weight, PMI, Braak AD score, CERAD plaque score), dentate EAAT2 level did not correlate with any of these variables in either the ET group or the control group, nor did it differ by gender (replicate cohort, all p values > 0.05), demonstrating that by definition these variables could not have been confounding factors in the observed case-control difference in the dentate EAAT2 levels. Consistent with the discovery cohort, we also found that the EAAT2 levels in the cerebellar cortex were lower in ET cases vs. those in controls in the replicate cohort (0.6 ± 0.2 vs. 1.0 ± 0.2, p < 0.001). We then combined our data from the discovery and replicate cohorts. ET cases had a 40% increase in the dentate EAAT2 levels and a 30% decrease in the cerebellar cortical EAAT2 levels when compared to controls (dentate: 1.4 ± 0.8 vs. 1.0 ± 0.5, p = 0.001; cerebellar cortex: 0.7 ± 0.2 vs. 1.0 ± 0.3, p < 0.001, both by Mann-Whitney U test) (Fig. 3B, C).

Fig. 3.

Differential regulation of EAAT2 levels in the dentate nucleus and cerebellar cortex. Paraffin-embedded sections immunolabeled with anti-EAAT2 antibodies were digitally scanned and the intensity of immunostaining in the dentate nucleus was quantified by tissue image analysis software. The intensity was normalized to the neighboring white matter regions. EAAT2 levels in ET cases (n = 61) were higher than controls (n = 25) in the replicate cohort (A). When combining the discovery and the replicate cohorts, ET cases had higher dentate EAAT2 levels and lower cerebellar cortical EAAT2 levels when compared to controls (B, C).

We assessed the relationship between dentate EAAT2 levels and several clinical and pathological variables in all 77 ET cases and 41 controls in this study. In ET cases, we did not find any correlation between dentate EAAT2 levels with either disease duration or total tremor scores (Spearman's r = 0.162, p = 0.170 and r = 0.068, p = 0.609, respectively). In all control and ET cases, we assessed the correlation between the dentate EAAT2 levels and cerebellar cortical EAAT2 levels. We found that dentate EAAT2 levels were marginally and inversely correlated with cerebellar cortical EAAT2 levels (Spearman's r = −0.177, p = 0.055). Dentate EAAT2 levels were associated with torpedo counts (Spearman's r = 0.195, p = 0.034), but not significantly with PC counts (Spearman's r = −0.123, p = 0.184). In a linear regression model, dentate EAAT2 levels differed by diagnosis, even after adjusting for torpedo count and PC count (beta = 0.30, p = 0.002). Interestingly, cerebellar cortical EAAT2 levels were correlated with PC counts (Pearson's r = 0.231, p = 0.012) and torpedo counts (Spearman's r = −0.325, p < 0.001) (Supplemental Table 1). In a linear regression model, cerebellar cortical EAAT2 levels differed by diagnosis, even after adjusting for torpedo count and PC count (beta = −0.10, p < 0.001).

Finally, we studied the relationship between EAAT2 expression and rs3794087 genotypes, which have been associated with ET [13–16]. We performed rs3794087 genotyping on 69 available ET cases and 24 controls, and we found that rs3794087 genotype frequency did not differ in ET cases and controls (p = 0.626, chi-square analysis) (Supplemental Fig. 2A). Because very few subjects (1 control and 2 ET cases) had the AA genotype, we pooled CA and AA genotypes for the further analysis. Subjects with CC genotype, when compared to those with CA and AA genotype combined, trended towards lower cerebellar cortical EAAT2 levels in controls (p = 0.134), higher cerebellar cortical EAAT2 levels in ET cases (p = 0.150), and lower dentate EAAT2 levels in ET cases (p = 0.181). However, none of these comparisons was statistically significant (Supplemental Fig. 2B-E). When ET cases and controls were combined, there were no associations between EAAT2 levels and rs3794087 genotypes either in the cerebellar cortex or in the dentate nucleus (Supplemental Fig. 2F, G).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we report an increased EAAT2 level in the ET dentate nucleus, in sharp contrast to the decreased EAAT2 levels in ET cerebellar cortex. The mechanism behind this differential expression pattern of EAAT2 in the ET cerebellar cortex vs. dentate nucleus remains to be investigated, but several possibilities will be discussed below.

The cell somata and proximal dendrites of neurons in the dentate nuclei receive dense inhibitory inputs from multiple PCs. The distal dendrite segments of the same neurons also receive excitatory inputs from the collaterals of mossy fibers and CFs. The balance between excitatory and inhibitory inputs to the dentate nucleus are critical in modulating dentate neuron spike frequency, and thus are important for cerebellar function and for proper motor control [21]. It is not known whether increased EAAT2 in the ET dentate nucleus is associated with diminished extracellular glutamate levels, but this possible physiological correlate of our findings should be explored.

In animal models with experimentally-induced brain hyperexcitability, EAAT2 levels have been shown to be up-regulated. This could reflect a compensatory protective response to excessive extracellular glutamate levels [24,25]. Therefore, the observed up-regulation of EAAT2 levels in ET dentate nucleus could also in theory be a compensatory response to long-standing excessive excitatory inputs. It is possible that astrocytes in the cerebellar cortex and those in the dentate nucleus react differently to hyperexcitability, and that the astrocytes in the ET cerebellar cortex fail to mount proper up-regulation of EAAT2, and this leads to a selective vulnerability of PCs to excitotoxic damage in ET. We found that dentate EAAT2 levels marginally and inversely correlated with cerebellar cortical EAAT2 levels, demonstrating the differential regulation of EAAT2 levels in these two brain regions. In addition, lower cerebellar cortical EAAT2 levels strongly associated with a lower PC counts and higher torpedo counts, indicating that cerebellar cortical EAAT2 levels might be directly regulating PC vulnerability to hyperexcitability whereas dentate EAAT2 levels might be a compensatory alteration. Nonetheless, these patterned changes of EAAT2 expressions in the ET cerebellum indicate that glutamatergic synaptic transmission might be disturbed at both the cerebellar cortex and the dentate nucleus.

Alternatively, increased EAAT2 levels in the ET dentate nucleus might not be the result of excessive hyperexcitability. β-alkaloids are a group of tremorogenic compounds that have been found to be elevated in ET brains [26]. Harmine exposure results in up-regulation of EAAT2 expression in astrocytes [27]. Whether an elevation in these compounds in the ET brain would differentially affect EAAT2 levels in dentate nucleus and cerebellar cortex in ET is not known.

Lastly, studies of mutant mice with PC degeneration demonstrate that multiple changes also occur at the level of cerebellar nuclei to compensate for reduced inhibitory input, including enlargement of remaining inhibitory synaptic boutons and increased aggregates of gephyrin protein that cluster GABAA receptors at synapses [28]. In essence, lower levels of inhibition of the dentate nucleus from PC loss in ET could trigger multiple compensatory responses that increase sensitivity to inhibitory inputs in order to restore the homeostatic level of inhibition. The effect of altered excitatory inputs in homeostatic responses in cerebellar nuclei is unknown. The marginally inverse correlation of higher dentate EAAT2 levels (i.e., potentially lower glutamate levels) and lower PC counts or higher PC torpedo counts (i.e., less inhibitory input due to PC loss) demonstrated in this study raises the possibility that increased EAAT2 expression in the ET dentate reflects an alternate compensatory mechanism towards maintaining excitation-inhibition balance in cerebellar nuclei.

A limitation of current study is that we did not use Western blot to quantify the EAAT2 levels due to the lack of available frozen tissue of dentate nuclei. Nonetheless, we have previously shown in the cerebellar cortex that EAAT2 levels on Western blot correlate highly with EAAT2 levels from the quantitative immunohistochemistry [19]. The present study has several strengths. First, the dentate nucleus is postulated to be an anatomical structure of importance in ET, but few pathological studies have investigated this area. Second, we attempt to link a genetic discovery to postmortem findings to better understand the pathomechanisms of ET.

In summary, EAAT2 levels are increased in the ET dentate nucleus, in contrast to the decreased EAAT2 levels in ET cerebellar cortex. Our studies reveal a differential regulation of EAAT2 in two cerebellar structures with highly differing anatomic organization and admixtures of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic influences. It is not known whether this contributes to a selective vulnerability of PCs to excitotoxic injury in this disease or how this may reflect physiologic function and/or pathologic changes in the dentate nucleus. Further studies are warranted to examine the role of dentate EAAT2 expression in ET and other cerebellar degenerative disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Kuo has received funding from the National Institutes of Health: NINDS #K08 NS083738 (principal investigator), and the Louis V. Gerstner Jr. Scholar Award,Parkinson's Disease Foundation, and International Essential Tremor Foundation, and NIEHS Pilot Grant ES009089 (principal investigator). Dr. Wang has received funding from the Jiangsu Government Scholarship for Overseas Studies, Qing Lan Project supported by the Jiangsu Provincial Department of Education, China and the Key Discipline Development Project of Jiangsu Province, China:JX10617801 (principal investigator). Dr. Louis has received research support from the National Institutes of Health: NINDS #R01 NS042859 (principal investigator), NINDS #R01 NS39422 (co-principal investigator), NINDS #R01 NS086736 (principal investigator), NINDS #R01 NS073872 (principal investigator), NINDS #R01 NS085136 (principal investigator) and NINDS #R01 NS088257(principal investigator). He has also received support from the Claire O'Neil Essential Tremor Research Fund (Yale University). Dr. Faust has received funding from the National Institutes of Health: NINDS #R21 NS077094 (principal investigator) and NINDS #R01 NS39422(co-principal investigator).

Abbreviation

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- CERAD

the Consortium to establish a Registry for Alzheimer's disease

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: Authors reported no financial conflicts.

Authors' roles: List all authors along with their specific roles in the project and preparation of the manuscript. These may include but are not restricted to: 1. Research project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; 2. Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; 3. Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the first draft, B. Review and Critique.

Jie Wang: 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 3B.

Geoffrey Kelly: 1C, 3B.

William Tate: 1C, 3B.

Michelle Lee: 1C, 3B.

Jesus Gutierrez: 1C, 3B.

Elan Louis: 1A, 1B, 2A, 2C, 3B.

Phyllis Faust: 1A, 1B, 1C, 3B.

Sheng-Han Kuo: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 3A.

Appendix A. Supplementary data: Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.09.003.

References

- 1.Louis ED, Ottman R, Hauser WA. How common is the most common adult movement disorder? estimates of the prevalence of essential tremor throughout the world. Mov Disord. 1998;13:5–10. doi: 10.1002/mds.870130105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filip P, Lungu OV, Manto MU, Bareš M. Linking essential tremor to the cerebellum: physiological evidence. Cerebellum. 2015 Nov;3 doi: 10.1007/s12311-015-0740-2. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louis ED, Faust PL, Vonsattel JPG, Honig LS, Rajput A, Robinson CA, Rajput A, Pahwa R, Lyons KE, Ross GW, Borden S, Moskowitz CB, Lawton A, Hernandez N. Neuropathological changes in essential tremor: 33 cases compared with 21 controls. Brain. 2007;130:3297–3307. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babij R, Lee M, Cortes E, Vonsattel JPG, Faust PL, Louis ED. Purkinje cell axonal anatomy: quantifying morphometric changes in essential tremor versus control brains. Brain. 2013;136:3051–3061. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuo SH, Erickson-Davis C, Gillman A, Faust PL, Vonsattel JPG, Louis ED. Increased number of heterotopic Purkinje cells in essential tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:1038–1040. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.213330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin CY, Louis ED, Faust PL, Koeppen AH, Vonsattel JPG, Kuo SH. Abnormal climbing fibre-Purkinje cell synaptic connections in the essential tremor cerebellum. Brain. 2014;137:3149–3159. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Louis RJ, Lin CY, Faust PL, Koeppen AH, Kuo SH. Climbing fiber synaptic changes correlate with clinical features in essential tremor. Neurology. 2015;84:2284–2286. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erickson-Davis CR, Faust PL, Vonsattel JPG, Gupta S, Honig LS, Louis ED. Hairy baskets associated with degenerative Purkinje cell changes in essential tremor. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69:262–271. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181d1ad04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuo SH, Tang G, Louis ED, Ma K, Babji R, Balatbat M, Cortes E, Vonsattel JPG, Yamamoto A, Sulzer D, Faust PL. Lingo-1 expression is increased in essential tremor cerebellum and is present in the basket cell pinceau. Acta, Neuropathol. 2013;125:879–889. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1108-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choe M, Cortes E, Vonsattel JPG, Kuo SH, Faust PL, Louis ED. Purkinje cell loss in essential tremor: random sampling quantification and nearest neighbor analysis. Mov Disord. 2016;31:393–401. doi: 10.1002/mds.26490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Symanski C, Shill HA, Dugger B, Hentz JG, Adler CH, Jacobson SA, Driver-Dunckley E, Beach TG. Essential tremor is not associated with cerebellar Purkinje cell loss. Mov Disord. 2014;29:496–500. doi: 10.1002/mds.25845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajput AH, Robinson CA, Rajput ML, Robinson SL, Rajput A. Essential tremor is not dependent upon cerebellar Purkinje cell loss. Park Relat Disord. 2012;18:626–628. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thier S, Lorenz D, Nothnagel M, Poremba C, Papengut F, Appenzeller S, Paschen S, Hofschulte F, Hussl AC, Hering S, Poewe W, Asmus F, Gasser T, Schöls L, Christensen K, Nebel A, Schreiber S, Klebe S, Deuschl G, Kuhlenbäumer G. Polymorphisms in the glial glutamate transporter SLC1A2 are associated with essential tremor. Neurology. 2012;79:243–248. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825fdeed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan EK, Foo JN, Tan L, Au WL, Prakash KM, Ng E, Ikram MK, Wong TY, Liu JJ, Zhao Y. SLC1A2 variant associated with essential tremor but not Parkinson disease in Chinese subjects. Neurology. 2013;80:1618–1619. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828f1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu SW, Chen CM, Chen YC, Chang CW, Chang HS, Lyu RK, Ro LS, Wu YR. SLC1A2 variant is associated with essential tremor in Taiwanese population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross JP, Rayaprolu S, Bernales CQ, Soto-Ortolaza AI, van Gerpen J, Uitti RJ, Wszolek ZK, Rajput A, Rajput AH, Rajput ML, Ross OA, Vilariño-Güell C. SLC1A2 rs3794087 does not associate with essential tremor. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:935 e9–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanai Y, Hediger MA. The glutamate and neutral amino acid transporter family: physiological and pharmacological implications. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;479:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng MM, Tang G, Kuo SH. Harmaline-induced tremor in mice: videotape documentation and open questions about the model. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (New York) 2013;3 doi: 10.7916/D8H993W3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee M, Cheng MM, Lin CY, Louis ED, Faust PL, Kuo SH. Decreased EAAT2 protein expression in the essential tremor cerebellar cortex. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:157. doi: 10.1186/s40478-014-0157-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharifi S, Nederveen AJ, Booij J, van Rootselaar AF. Neuroimaging essentials in essential tremor: a systematic review. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;5:217–231. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng N, Raman IM. Synaptic inhibition, excitation, and plasticity in neurons of the cerebellar nuclei. Cerebellum. 2010;9:56–66. doi: 10.1007/s12311-009-0140-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miwa H. Rodent models of tremor. Cerebellum. 2007;6:66–72. doi: 10.1080/14734220601016080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furuta A, Martin LJ, Lin CL, Dykes-Hoberg M, Rothstein JD. Cellular and synaptic localization of the neuronal glutamate transporters excitatory amino acid transporter 3 and 4. Neuroscience. 1997;81:1031–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreira JD, de Siqueira LV, Lague VM, Porciúncula LO, Vinadé L, Souza DO. Short-term alterations in hippocampal glutamate transport system caused by one-single neonatal seizure episode: implications on behavioral performance in adulthood. Neurochem Int. 2011;59:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doi T, Ueda Y, Takaki M, Willmore LJ. Differential molecular regulation of glutamate in kindling resistant rats. Brain Res. 2011;1375:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Louis ED, Factor-Litvak P, Liu X, Vonsattel JPG, Galecki M, Jiang W, Zheng W. Elevated brain harmane (1-methyl-9H-pyrido[3,4-b]indole) in essential tremor cases vs, controls. Neurotoxicology. 2013;38:131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Sattler R, Yang EJ, Nunes A, Ayukawa Y, Akhtar S, Ji G, Zhang PW, Rothstein JD. Harmine, a natural beta-carboline alkaloid, upregulates astroglial glutamate transporter expression. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:1168–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garin N, Hornung JP, Escher G. Distribution of postsynaptic GABA(A) receptor aggregates in the deep cerebellar nuclei of normal and mutant mice. J Comp Neurol. 2002;447:210–217. doi: 10.1002/cne.10226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.