Abstract

Many recent studies have emphasized the importance of genetic variants and mutations in cancer and other complex human diseases. The overwhelming majority of these variants occur in non-coding portions of the genome, where they can have a functional impact by disrupting regulatory interactions between transcription factors (TFs) and DNA. Here, we present a method for assessing the impact of non-coding mutations on TF-DNA interactions, based on regression models of DNA-binding specificity trained on high-throughput in vitro data. We use ordinary least squares (OLS) to estimate the parameters of the binding model for each TF, and we show that our predictions of TF-binding changes due to DNA mutations correlate well with measured changes in gene expression. In addition, by leveraging distributional results associated with OLS estimation, for each predicted change in TF binding we also compute a normalized score (z-score) and a significance value (p-value) reflecting our confidence that the mutation affects TF binding. We use this approach to analyze a large set of pathogenic non-coding variants, and we show that these variants lead to significant differences in TF binding between alleles, compared to a control set of common variants. Thus, our results indicate that there is a strong regulatory component to the pathogenic non-coding variants identified thus far.

Keywords: TF-DNA binding, non-coding variants, regression models

1 Introduction

Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) play important roles in the pathogenesis of many complex diseases [16]. For mutations that occur within protein-coding genes, there are established metrics (e.g. SIFT [29] and PolyPhen [1]) that attempt to quantify the effect of a variant on gene function. However, coding variants are only a small fraction of all genetic variants: recent studies estimate that ~93% of disease- and trait-associated human genetic variants fall within non-coding genomic regions [24], and their functional impact is difficult to assess and quantify.

Non-coding variants can play a functional role in the cell by disrupting interactions between transcription factors (TFs) and their genomic target sites [16]. TFs are regulatory proteins that bind short DNA sites, typically in the neighborhood of the regulated genes, and promote or repress gene expression. Predicting the effect of SNVs on TF binding is an important area of research still lacking good solutions. Binding models for many human TFs are currently available [14, 22, 31, 41] in the form of position weight matrices (PWMs). A PWM is a matrix of scores (or weights) for each nucleotide at each position in a TF binding site. Although they are easy to use and visualize, PWMs make the assumption that individual base pairs in a TF binding site (TFBS) contribute independently to the binding affinity. This assumption does not always hold [5, 11, 37, 38, 42]. Nevertheless, although it is now recognized that PWMs cannot accurately capture TF-DNA binding affinity [20,33,35], current methods for determining whether a SNV is likely to affect TF-DNA binding are based on differences in PWM scores [2, 26, 36, 39]. Such methods are generally able to detect large changes in TF binding affinity (from high affinity to non-specific binding), but they ignore less drastic changes, which can have important phenotypic effects (e.g. [32]).

Another drawback of using PWM models to predict the effect of SNVs is the fact that many mammalian TFs have several PWMs available in the literature, oftentimes from databases such as Transfac [23], Jaspar [21], UniPROBE [28], or Cis-BP [41]. Different PWMs can result in different predictions on whether or not a SNV will affect binding of the TF of interest, and there is no objective method to choose the best PWM to use, as quality metrics are not reported for these models. Ideally, a method for characterizing the effect of non-coding SNVs on TF binding should be able to capture both large and small changes in binding, as long as the changes are ‘significant’ given the quality/precision of the model.

Here, we present a new method for assessing the impact of non-coding variants/mutations on TF-DNA binding. Based on high-throughput data from protein-binding microarray (PBM) experiments [8,9], we build k-mer-based models of TF binding specificity, estimating the model parameters with ordinary least squares (OLS). We use the estimated regression coefficients, as well as the variance-covariance matrix, to compute for any given mutation: 1) a quantitative prediction of the change in TF binding due to the mutation, and 2) a z-score and p-value indicating the significance of the predicted change, given the model properties. Our approach is novel compared to previous regression models trained on PBM data [3, 40] because, by using OLS, we obtain not only estimates of the regression coefficient for each k-mer, but also the variance of the coefficient estimates. Thus, our predictions of the effects of mutations on TF-DNA binding implicitly take into account the quality of the training data and model, such that in the case of poor predictive models we require a larger change in binding for a mutation to be called significant. In addition, the computed variance in the estimates of the model parameters allows us to make objective choices between different models corresponding to the same TF. We validate our models using gene expression data from high-throughput reporter assays [15,27], and we apply them to predict the effects of pathogenic SNVs [34] on TF binding.

2 Data and Methods

2.1 Universal protein-binding microarray (PBM) data

Accurate methods for predicting the effect of SNVs on TF binding require accurate models of TF-DNA binding specificity. Here, to train such models we use high-throughput in vitro data from universal PBM assays [9]. Each universal PBM data set is specific to one TF, and it contains quantitative measurements of the binding specificity of that TF for ~40,000 DNA sequences. The PBM protocol is described in detail in [8]. Briefly, double-stranded DNA molecules attached to a glass slide (microarray) are incubated with an epitope-tagged TF. To detect the amount of TF bound to each DNA spot, the microarray is labeled with a uorophore-conjugated antibody specific to the epitope tag, and scanned using a microarray scanner. The uorecence intensity of each DNA spot provides a quantitative measurement of the TF specificity for the DNA sequence in that spot.

PBM experiments are typically performed using Agilent microarrays printed with custom 60-bp DNA sequences [8]. For a ‘universal’ PBM array design, the DNA sequences printed on the array are computationally designed according to a deBruijn sequence of order 10 over the {A,C,G,T} alphabet, which, by definition, is guaranteed to contain all possible 10-bp DNA sequences, with each 10-mer occurring once and only once. To computationally generate the DNA library, the deBruijn sequence is split into sequences of 35 or 36 bases, depending on the design [9, 41], and the remaining 25 or 24 bases, respectively, are set to the complement of a primer used to double-strand the DNA molecules. Table 1 shows as example one of the 973 PBM data sets [6,41] used in our analysis of pathogenic non-coding variants (Sect. 3.4). The PBM data sets used in Sects. 3.2 and 3.3 are: pTH5080_HK and pTH5080_ME for Creb [41], Tcf1_2666.2 for Hnf1 [7], Foxa2_2830.2_v1 for Foxa, Hnf4a_2640.2_v1 for Hnf4, and Gata3_1024.3_v1 for Gata [5].

Table 1.

Example of universal PBM data set for transcription factor Arid5a [5].

| DNA sequences of length L=60 | TF binding intensity |

|---|---|

| TTGAATCAAT……GTCCGTGCTG | 74573.8653 |

| CCAAGACAGT……GTCCGTGCTG | 45399.3011 |

| CGCAAATATT……GTCCGTGCTG | 40440.2397 |

| …… | …… |

| ACTTCCGATA……GTCCGTGCTG | 39895.9250 |

2.2 Massively parallel reporter assay (MPRA) data

To validate that the quantitative predictions of TF-binding changes made using our OLS k-mer models (Sect. 2.3) are biologically relevant, we leveraged high-throughput gene expression data from massively parallel reporter assays (MPRA) [27]. Briefly, in an MPRA experiment one first synthesizes tens of thousands of oligonucleotides that contain a library of regulatory elements (enhancers), each coupled to a short DNA tag. The oligonucleotides are used to generate a pool of plasmids, where each plasmid contains one of the regulatory elements of interest upstream of an open reading frame followed by the sequence tag corresponding to that regulatory element. The pool of plasmids is co-transfected into cells, where the regulatory elements drive transcription of mRNA molecules containing the tags. The tags in the reporter mRNAs, as well as the original plasmid pool, are sequenced and counted. The ratio of these counts, or the logarithm of the ratio, is taken as a measurement of the gene expression driven by each regulatory element [27].

Here, we use MPRA data from two recent studies. Melnikov et al. [27] reported the expression levels of a reporter gene (an inert open reading frame) downstream of variants of a synthetic, 87-nt cAMP-regulated enhancer. The mutants were either generated by single nucleotide substitutions (for a total of 87 × 3 = 261 variants) or by random multiple 1-bp nucleotide substitutions, introduced at a rate of 10% per position (~27,000 variants). The expression level of each variant was reported as the median of the mRNA-based counts normalized by the DNA-based counts, taken over multiple tags. In our analyses, we used the natural logarithm of the ratios of the expression levels of mutants to the expression level of the wild-type sequence.

Kheradpour et al. [15] reported the expression levels of a small number of enhancer variants for four TFs: Hnf1, Foxa, Hnf4 and Gata. Selected wild-type enhancer regions were centered on motif matches and the mutants were generated by multiple approaches such as motif removal, maximum 1-bp decrease, least 1-bp change, etc. The expression level was expressed as the binary logarithm of the mean value of the ratio of the mRNA to plasmid counts. In our analyses, we used the proportion of change in gene expression due to the mutations, relative to the expression of the wild-type sequence.

2.3 Training k-mer regression models of TF binding specificity using ordinary least squares (OLS)

In a universal PBM experiment, TF binding to each of the ~40,000 pre-designed L-bp DNA sequence is measured as fluorescent signal (Table 1). We apply a logarithmic transformation to the fluorescent signal, which makes the experimental noise uncorrelated with the signal, and we use the natural log-transformed fluorescence intensities as the dependent variable Y. As independent variables X, we use the counts of each k-mer within the L-bp DNA sequences, with the value of k decided based on validation experiments (Sect. 3.1). Since the DNA is double-stranded, and binding of TFs is not strand-specific, we regard each sequence and its reverse complement as the same feature. Thus, the number of features nk for a k-mer model is 4k/2 when k is an odd number, and (4k − 2k)/2 + 2k when k is even.

Suppose there are a total of N L-bp sequences. We convert each sequence into the counts of all nk k-mers in an overlapping fashion, generating a N × nk covariate matrix X. There is an inherent restriction for the rows of the matrix. For any row i, the sum of the counts is xi1 + … + xink = L − k + 1, which is due to the fact that every L-bp sequence contains L − k + 1 overlapping k-mers. The linear dependency of the nk features renders the intercept term redundant, and we therefore train our models without the intercept term:

| (1) |

After the intercept term is removed from the model, multicollinearity among the covariates is no longer a problem and we can compute the ordinary least square (OLS) estimates for the β’s, as well as the covariance matrix Σ̂, whose diagonal contains the variance in the coefficient estimates:

| (2) |

| (3) |

2.4 Statistical testing using OLS k-mer models of TF binding specificity

By assuming normality on the error vector ε ~ N(0, σ2I) in (1), we can perform statistical tests on β’s as well as linear combination of β’s. Given a vector c of length nk, the null and alternative hypotheses to test a linear combination of β’s are the following:

A t-statistic can be built using the estimated covariance matrix:

| (4) |

In fact, since we have a large number of observations, the distribution of the test statistics is approximately normal, and we can thus compute a z-score for c′ β̂.

2.5 Using OLS k-mer models to predict the effect of SNVs on TF-DNA binding

The method above can be directly applied to predict the effect of single base-pair variants on TF binding. To illustrate this, we provide an example for a mutation (A to C) that affects a binding site for TF Creb1 (Table 2). We used 6-mer features to train a regression model from universal PBM data for Creb1, available from [41]. In a 6-mer model, there are a total of 2080 features. From the modeling step, we can derive the estimates of coefficients β̂ for all 6-mers, as well as the covariance matrix estimate Σ̂.

Table 2.

Single base-pair mutation overlapping a binding site for TF Creb1. The wild-type and mutated binding sites are shown in bold. The mutated position is underlined. (The 6-mers in parentheses are the reverse complements of 6-mers in the original sequence. In these cases the reverse complement 6-mers were used as features because they are alphabetically ranked lower that the corresponding 6-mers on the forward strand.)

| Wild-Type | Mutant |

|---|---|

| CCCATTGACGTCAATGGG | CCCATTGCCGTCAATGGG |

| CATTGA | CATTGC |

| ATTGAC | ATTGCC |

| TTGACG (CGTCAA) | TTGCCG (CGGCAA) |

| TGACGT (ACGTCA) | TGCCGT (ACGGCA) |

| GACGTC | GCCGTC (GACGGC) |

| ACGTCA | CCGTCA |

Given a k-mer model, a single base-pair mutation leads to a change in every k-mer in a 2k − 1 bp region centered at the mutated base (Table 2). Thus, the total change is:

where jp is the index of the pth k-mer in the mutated sequence, and ip is the index of the corresponding k-mer in the original sequence.

For the example in Table 2, the mutation causes a change in 6 consecutive 6-mers, and the total effect of the mutation is:

In vector notation, this effect can be written in terms of 6-mer coefficients as:

where the coefficients are null for all 6-mers that do not contribute to the total effect.

Next, we use (4) to compute the test statistic t for the difference in predicted binding affinity (c′ β̂) between the mutant and the wild-type sequences. For the specific mutation in our example, the difference in binding affinity is −1.69. After normalization, the z-score for this mutation is −42.07 (p-value < 10−10), indicating a significant decrease in Creb1 binding affinity.

3 Results

3.1 OLS 6-mer models can accurately predict TF binding intensity

To check the accuracy of the k-mer models and determine the best value for k, we used 115 TFs from the Cis-BP database [41] for which universal PBM data is available from two distinct array designs. We learned OLS k-mer models from one array design, and tested them on the independent data obtained using the second array design. The Pearson correlation coefficient (R) between our predicted TF binding intensities and the measured intensities from both the training and the test data sets are summarized in Fig. 1. We note that PBM experiments performed on different arrays are not replicate experiments, as the array designs contain different DNA sequences. In addition, data quality is highly variable across the PBM data sets, so we expect the performance of any model trained on these data sets to also vary. Importantly though, our 6-mer OLS models are designed to implicitly take data quality into account when predicting changes in TF binding due to mutations, as described in Sect. 2.5.

Fig. 1.

Performance of OLS k-mer models for k = 5, 6, and 7. Box plots show Pearson correlation coefficients between predicted and measured TF binding intensities, for 115 TFs [41] with data available from two universal PBM designs. Left: predictions compared to binding data from the PBM design used for training. Right: predictions compared to binding data from an independent PBM design.

Figure 1 shows the performance of 5-mer, 6-mer, and 7-mer OLS models, which have 512, 2080, and 8192 features, respectively. For k = 8, the models have a total of 32,896 features. Since we only have ~40,000 observations, models with k ≥ 8 run into dimensionality problems and we cannot get OLS estimates for the parameters. Among 5-mer, 6-mer, and 7-mer models, we found that 7-mers models perform best on the training data (Fig. 1, left panel). However, on independent test data from a different array design, 7-mer models perform worse than 6-mers models (Fig. 1, right panel), indicating that they are likely over-fitting the data. Thus, our results indicate that k = 6 results in models that have the best accuracy in predicting TF binding intensity for new DNA sequences. All results presented below use 6-mer OLS models.

The main goal of our method is to predict changes in TF binding, not absolute TF binding levels. Nevertheless, to ensure that our 6-mer OLS models are accurate in predicting TF binding levels, we compared them to previous models trained and tested on PBM data from different array designs. For this comparison, we used the PBM data from the DREAM5 TF-DNA Motif Recognition Challenge [40], which includes independent data sets obtained using two different array designs, for 66 mouse TFs. In the challenge, PBM intensity data were provided only for one array design, and the performance of each algorithm was evaluated by assessing the prediction accuracy on the other array design, using the Pearson correlation coefficient (R). Weirauch et al. [40] used several normalization techniques to transform the PBM data before using it for training and testing, and for each algorithm they selected the combination of normalization steps that resulted in the best prediction accuracy on the test data. In contrast to their approach, we use the PBM data directly in our algorithm, applying only a logarithmic transformation to all PBM intensities, and thus keeping the test PBM data completely independent from the training step. The performance of our 6-mer OLS method was above average compared to the 15 methods tested in [40]. Thus, we conclude that the accuracy of our method in predicting TF binding intensity is comparable to existing algorithms, with our method having the unique advantage that it implicitly incorporates data quality into the TF binding models.

3.2 TF binding change predictions based on OLS 6-mer models correlate well with gene expression changes

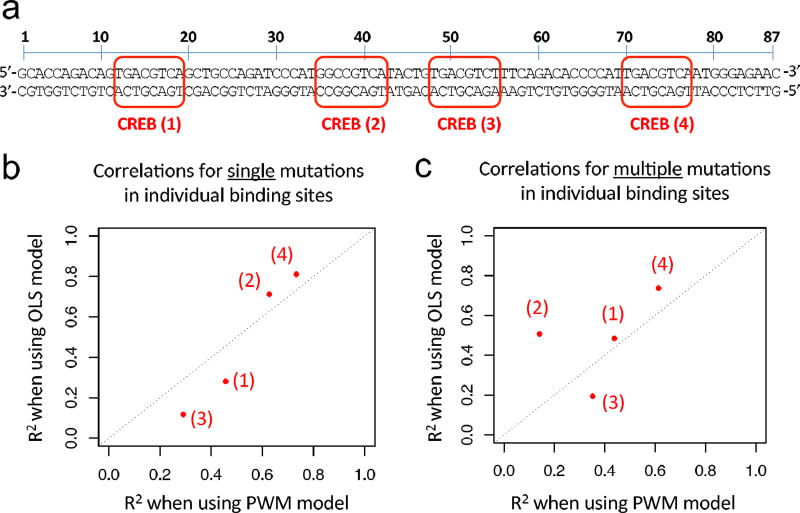

To validate that our OLS 6-mer models are able to quantitatively predict the effect of nucleotide mutations, we leveraged high-throughput reporter expression data generated using massively parallel reporter assays (MPRA) [15, 27]. First, we focused on MRPA data for an 87-bp synthetic enhancer that contains four binding sites for transcription factor Creb1 [27]. Melnikov et al. [27] reported expression measurements for the wild-type enhancer (Fig. 2a), for all possible single base pair mutations, as well as a large number of enhancer variants with multiple mutations randomly distributed across the enhancer region. The expression values are reported as ratios of tag counts in the reporter mRNA versus tag counts in the plasmid pool (see Sect. 2.2). Based on the expression values reported in [27], we computed for each mutant enhancer the natural logarithm of the ratio between the expression of the mutant and the expression of the wild-type enhancer. We asked whether these changes in gene expression can be explained, at least in part, by changes in Creb1-DNA binding predicted according to: 1) our OLS 6-mer model for TF Creb1; and 2) the mouse Creb1 PWM reported in the Cis-BP database (motif identifier M0297_1.02) [41]). To score DNA sites according to the PWM we used the log-likelihood (LLR) score, i.e. we computed the base 2 logarithm of the ratio between the probability of the site according to the PWM model, and the probability of the site according to a uniform background model over the four nucleotides.

Fig. 2.

Correlations between measured gene expression changes and TF binding changes predicted by OLS and PWM models, for individual TF binding sites. (a) Creb1-regulated enhancer. Red rectangles mark the four annotated Creb1 binding sites. (b) Correlations for variant enhancers with single 1-bp mutations in individual binding sites. (c) Correlations for variant enhancers with multiple 1-bp mutations in individual binding sites. R2 represents the squared Pearson correlation coefficient between measured change in gene expression and predicted change in TF binding.

Before applying our approach to predict the effect of mutations on Creb1-DNA binding, we verified the accuracy of Creb1 OLS 6-mer models trained on PBM data, and we selected the most accurate model. There are two universal PBM datasets available for mammalian Creb1, from two distinct universal designs, denoted HK and ME [41] (Sect. 2.1). We trained OLS 6-mer models on each array design, and we compared the models according to their predicted variance for the parameter estimates, i.e. the diagonal of the covariance matrix Σ̂ (see (3)). The parameter estimates for the model trained on the ME data set showed lower variances (Mann-Whitney U test p-value < 2.2 × 10−16), and thus it was selected as the final Creb1 OLS 6-mer model.

We first compared the OLS and PWM models on variant enhancers with single bp mutations in each of the four Creb1 binding sites (defined as shown in Fig. 2a). For each binding site, we asked how well the measured gene expression changes due to 1-bp mutations within the binding site correlate with the predicted changes in TF binding. The OLS model performed better than the PWM for mutations in sites 2 and 4 (where both models have good prediction) and worse than the PWM for mutations in sites 1 and 3 (where both models performed poorly) (Fig. 2b).

Next, we compared the OLS and PWM models on enhancers with multiple 1-bp mutations in each of the four Creb1 binding sites. The OLS model outperformed the PWM on three of the four binding sites (Fig. 2c). This result was somewhat expected. Unlike our OLS k-mer models, PWM models cannot capture dependencies between positions within TF binding sites, and this short-coming can lead to poor predictions when multiple mutations are introduced in a site.

Finally, we compared the OLS and PWM models on enhancers with multiple 1-bp mutations in regions that cover several of the Creb1 binding sites (Fig. 3). For such regions, using the OLS 6-mer model is straightforward, since the model can be applied to predict TF binding for sequences of any width. In contrast, PWM models have a fixed width. To apply the PWM model to longer regions, we used a sliding window of size 8 (the same size as the Creb1 PWM), we scored each window according to the PWM, and we summed up the scores above a certain cutoff, expressed in terms of the maximum LLR score that can be obtained using the PWM model (e.g. 20% the maximum score, 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, etc.). We also tested other approaches to score long DNA regions using PWMs, such as the GOMER model [13], but the thresholding approach described above worked best. We found that a cutoff of 60% leads to the best performance of the PWM model, so we used this cutoff in our comparisons. Figure 3 shows that as we include more binding sites in our analysis, the performance of the PWM decreases, reaching an R2 of 0.27 when all four binding sites are included (Fig. 3c, left panel). In contrast, the OLS model continues to perform well regardless of the number of binding sites included in the analysis, and it constantly achieves correlations of 0.49 or higher (Fig. 3, right panels). We also tested additional Creb1 PWM models, including the curated human Creb1 motif from the HocoMoco database [17] (downloaded from Cis-BP [41], motif identifier M6180_1.02), which achieved correlations < 0.1 in all analyses of mutations in multiple binding sites. Overall, the Cis-BP motif M0297 1.02 resulted in the highest correlations with the gene expression data. Thus, we focused on this motif for all comparisons described in this section.

Fig. 3.

Correlations between gene expression changes and TF binding changes predicted by OLS and PWM models, for regions containing multiple TF binding sites and multiple mutations. (a) Correlations for variant enhancers with multiple 1-bp mutations at positions 35–55 in the Creb1-regulated enhancer (see Fig. 2a), covering two Creb1 binding sites. (b) Similar to panel (a), but for mutations at positions 35–77 in the Creb1-regulated enhancer, covering 3 binding sites. (c) Similar to panel (a), but for mutations at positions 12–77 in the Creb1-regulated enhancer, covering 4 binding sites. Gray lines show the linear fit obtained using the R lm function. R2 represents the squared Pearson correlation coefficient.

Our results show that changes in TF binding, predicted using the OLS 6-mer model, can explain ~50% of the change in gene expression due to DNA mutations. This fraction is remarkable, given the complexity of gene regulation. We do not expect TF binding changes to completely explain gene expression changes, nor to correlate linearly with expression changes observed in the cell. The large correlation between changes predicted by the OLS model and measured changes in gene expression demonstrate that our predictions are quantitative and biologically relevant.

3.3 Making binary predictions of TF binding changes using OLS 6-mer models

Another application of our 6-mer OLS models is binary classification of mutations into those that affect TF binding (and thus are likely to affect gene expression) versus those that do not affect TF binding (and thus are less likely to affect gene expression). To illustrate this application of our models, we used MRPA data generated by Kheradpour et al. [15] for putative regulatory regions centered at binding sites for four TFs (Hnf1, Foxa, Hnf4 and Gata), and variants of these regions where the TFBSs are mutated. Several types of mutants were tested for each regulatory region: scrambled binding site, removal of binding sites, 1-bp mutations that caused the maximum increase or decrease in PWM score, 1-bp mutation that caused the minimum change in PWM score, and a random 1-bp change. Thus, compared to the MPRA data used in Sect. 3.2, the data used here does not comprehensively cover all possible single-bp mutations. In addition, unlike the well-characterized Creb1-regulated enhancer used in Sect. 3.2, the genomic regions included in this MPRA data set [15] are putative enhancers. Thus, some of the enhancers may not be active, or they may not be regulated through the TFBSs in the tested genomic regions. For this reason, we filtered out the wild-type regulatory sequences with expression levels lower than 0.5, as suggested by the authors [15]. In addition, for both wild-type and mutant sequences, we used the replicate MPRA data sets to filter out sequences for which the replicates did not agree (p-value < 0.05 according to a Mann-Whitney U test applied to the reporter expression data for the two replicates, over the 10 different tags used for each sequence).

After the filtering steps described above, the number of sequences for each TF was: 27 (wild-type,mutant) pair sequences for Hnf1, 53 pairs for Hnf4, 29 pairs for Gata, and 20 pairs for Foxa. For each TF, the set of (wild-type,mutant) pairs was dichotomized into pairs for which the wild-type and mutant sequences have either similar or distinct expression values. The calls were made using a Mann-Whitney U test that compared the expression values of the two sequences, over all tags used in the MPRA experiment. The U test p-value cutoff was set individually for each TF, as the 5% quantile of the empirical distribution of p-values obtained by testing the differences between replicate experiments. Thus, for each TF we obtained a ’positive’ set of (wild-type,mutant) pairs, for which the mutation significantly affected gene expression, and a ’negative’ set of (wild-type,mutant) pairs, for which the mutation did not have an effect on gene expression.

Next, using the dichotomized expression data for (wild-type,mutant) pairs, we asked whether differences in TF binding, as predicted by our 6-mer OLS models or by PWMs of the four TFs (Hnf1, Foxa, Hnf4 and Gata), are predictive of changes in gene expression. To evaluate each binding model we used the area under the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve for low false positive rates (<0.2). For each mutation, we predicted that it either has or does not have an effect on TF binding and gene expression, according to whether the predicted TF-binding change is above a cutoff. For PWM models we used cutoffs for the LLR score. For OLS 6-mer models we used cutoffs according to the z-score. As shown in Table 3, for three of the four TFs our OLS models outperformed the PWM models.

Table 3.

Comparison between 6-mer OLS models and PWM models for four TFs with MPRA data available from [15]. The numbers represent areas under the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve, for false positive rates between 0 and 0.2. The maximum value for the area under the curve is 0.2. The expected value for random models is 0.02. Results show that 6-mer OLS models outperform PWM models for 3 out of the 4 TFs tested.

| Hnf1 | Hnf4 | Gata | Foxa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PWM models | 0.04556 | 0.02082 | 0.07014 | 0.04835 |

| 6-mer OLS models | 0.06667 | 0.04868 | 0.05046 | 0.05275 |

3.4 Analysis of pathogenic non-coding variants

To further illustrate how OLS models can be used to analyze non-coding variants, we performed a broad analysis of all non-coding pathogenic SNVs annotated in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD®) [34] and ClinVar [18]. Starting with 101,833 SNVs, we excluded any variants that overlapped with consensus coding sequences, leaving 4,655 unique variants. Next, we removed variants considered to reside within coding/canonical splice of any Ensembl coding transcript. We also excluded the variants on sex chromosomes or mitochondrial chromosomes, leaving a total of 3,422 unique non-coding pathogenic autosomal variants for analysis.

We also selected a set of control variants among the common variants annotated in the 1000 Genomes Project [4], following similar filtering steps. We first downloaded all SNVs from phase 3 of the 1000 Genomes Project, and excluded all rare variants (i.e. variants with minor allele frequency < 0.01). To obtain non-coding variants, we annotated the filtered variants using the Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) tool [25], and we excluded variants annotated to reside in a coding region. After this process, a total of 11.9 million non-coding SNVs were retained from 84.4 million 1000 Genomes variants. Finally, we randomly selected 3,422 non-coding autosomal variants that followed a similar genomic distribution as the pathogenic variants.

We trained 6-mer regression models for all 973 PBM data sets avaialble for human and mouse TFs [6, 41], and applied our models to predict the binding changes due to SNVs in the pathogenic and control data sets. For each SNV, we took the maximum absolute value of the 973 predicted z-scores as the measure of the binding change due to the SNV. Figure 4 displays the empirical cumulative density functions of the predicted binding changes for the 3,422 variants in each data set. Our result shows that the binding changes caused by the pathogenic variants are significantly larger than the changes caused by the control variants (Mann-Whitney U test p-value < 2.2 × 10−16), indicating that there is a strong regulatory component for the annotated pathogenic variants.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of predicted TF binding changes between pathogenic SNVs (red line) and control SNVs (blue line). Overall, pathogenic SNVs have a larger effect on TF binding, as predicted by our OLS 6-mer models.

4 Discussion

We developed a new method to assess the impact of non-coding mutations on TF-DNA binding, using high-throughput PBM data. Such data is currently available for almost 1,000 mammalian TFs [6, 41] covering a broad range of TF families. Each PBM data set contains binding measurements for ~40,000 short DNA sequences. We utilize the data to build k-mer linear regression models, estimating the model parameters with OLS. The novelty of our approach, compared to previous work [3, 40], is that we can use the estimated regression coefficients together with the estimated covariance matrix to compute not only the change in TF binding due to a mutation (or set of mutations), but also a z-score and a p-value indicating the significance of the change.

Importantly, for any given mutation, the z-scores and p-values obtained for different TFs are directly comparable and can be combined to assess the broad regulatory effects of mutations, as illustrated in Sect. 3.4. In contrast, given that PWM scores are not directly comparable across different models, combining differences in PWM scores for large sets of TFs is not straightforward. As another advantage of OLS k-mer models over PWMs, we note that our k-mer models can be used to assess the effect of mutations over long regions containing multiple mutations and binding sites, without the need to call binding sites according to some score cutoff. As shown in Sect. 3.2 for mutations in an enhancer regulated by Creb1, our OLS model was able to quantitatively capture the effects of DNA mutations over long regions, explaining ~50% of the change in gene expression. Thus, we we expect any method that uses PWM models to assess the functional effects of non-coding variants (e.g. [10, 12, 25,30]) to benefit from using our OLS models instead of PWMs.

We note that individual k-mer features in our models are not independent, so their estimated coefficients (β̂) should not be interpreted individually. Overall, though, the change in binding score and the corresponding z-scores and p-values, computed as described in Sect. 2.5, can be interpreted directly because they take into account all overlapping k-mers affected by the mutation of interest, and the z-scores and p-values also take into consideration the correlation between features through the estimated variance-covariance matrix. One concern about the z-scores and p-values is their dependence on the normality of the random error, which can be approximately achieved by exploring the transformation of the raw intensity score. In our study we did not elaborate on finding the optimal transformation, since we have a sufficiently large sample size for the statistical tests to be applicable even in cases of non-normality [19]. The main limitation of our OLS approach is that the number of features cannot exceed the number of observations. In future work we will focus on Bayesian methods that can be applied to higher dimensional data, while at the same time providing posterior distributions that allow us to make inferences about the model parameters.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by awards number P01CA142538 from the National Cancer Institute, and R01GM117106 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (to RG). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health.

References

- 1.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods. 2010;7(4):248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen MC, Engstrom PG, Lithwick S, et al. In silico detection of sequence variations modifying transcriptional regulation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008;4(1):e5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0040005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annala M, Laurila K, Lahdesmaki H, Nykter M. A linear model for transcription factor binding affinity prediction in protein binding microarrays. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(5):e20,059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526(7571):68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badis G, Berger MF, Philippakis AA, et al. Diversity and complexity in DNA recognition by transcription factors. Science. 2009;324(5935):1720–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.1162327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrera LA, Vedenko A, Kurland JV, et al. Survey of variation in human transcription factors reveals prevalent DNA binding changes. Science. 2016;351(6280):1450–1454. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger MF, Badis G, Gehrke AR, et al. Variation in homeodomain DNA binding revealed by high-resolution analysis of sequence preferences. Cell. 2008;133(7):1266–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger MF, Bulyk ML. Universal protein-binding microarrays for the comprehensive characterization of the DNA-binding specificities of transcription factors. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(3):393–411. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berger MF, Philippakis AA, Qureshi AM, et al. Compact, universal DNA microarrays to comprehensively determine transcription-factor binding site specificities. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24(11):1429–1435. doi: 10.1038/nbt1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyle AP, Hong EL, Hariharan M, et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012;22(9):1790–1797. doi: 10.1101/gr.137323.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bulyk ML, Johnson PL, Church GM. Nucleotides of transcription factor binding sites exert interdependent effects on the binding affinities of transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(5):1255–1261. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.5.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu Y, Liu Z, Lou S, et al. FunSeq2: a framework for prioritizing noncoding regulatory variants in cancer. Genome Biol. 2014;15(10):480. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0480-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granek JA, Clarke ND. Explicit equilibrium modeling of transcription-factor binding and gene regulation. Genome Biol. 2005;6(10):R87. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-10-r87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jolma A, Yan J, Whitington T, et al. DNA-binding specificities of human transcription factors. Cell. 2013;152(1–2):327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kheradpour P, Ernst J, Melnikov A, et al. Systematic dissection of regulatory motifs in 2000 predicted human enhancers using a massively parallel reporter assay. Genome Res. 2013;23(5):800–811. doi: 10.1101/gr.144899.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khurana E, Fu Y, Chakravarty, et al. Role of non-coding sequence variants in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016;17(2):93–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2015.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulakovskiy IV, Medvedeva YA, Schaefer U, et al. HOCOMOCO: a comprehensive collection of human transcription factor binding sites models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):195–202. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Benson M, et al. ClinVar: public archive of interpretations of clinically relevant variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D862–868. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lumley T, Diehr P, Emerson S, Chen L. The importance of the normality assumption in large public health data sets. Annu Rev Public Health. 2002;23:151–169. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maerkl SJ, Quake SR. A systems approach to measuring the binding energy landscapes of transcription factors. Science. 2007;315(5809):233–237. doi: 10.1126/science.1131007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathelier A, Fornes O, Arenillas DJ, et al. JASPAR 2016: a major expansion and update of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D110–115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathelier A, Zhao X, Zhang AW, et al. JASPAR 2014: an extensively expanded and updated open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D142–147. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matys V, Kel-Margoulis OV, Fricke E, et al. TRANSFAC and its module TRANSCompel: transcriptional gene regulation in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Database issue):D108–110. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maurano MT, Humbert R, Rynes E, et al. Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science. 2012;337(6099):1190–1195. doi: 10.1126/science.1222794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLaren W, Gil L, Hunt SE, et al. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):122. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0974-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McVicker G, van de Geijn B, Degner JF, et al. Identification of genetic variants that affect histone modifications in human cells. Science. 2013;342(6159):747–749. doi: 10.1126/science.1242429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melnikov A, Murugan A, Zhang X, et al. Systematic dissection and optimization of inducible enhancers in human cells using a massively parallel reporter assay. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30(3):271–277. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newburger DE, Bulyk ML. UniPROBE: an online database of protein binding microarray data on protein-DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):77–82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perera D, Chacon D, Thoms JA, et al. OncoCis: annotation of cis-regulatory mutations in cancer. Genome Biol. 2014;15(10):485. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0485-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robasky K, Bulyk ML. UniPROBE, update 2011: expanded content and search tools in the online database of protein-binding microarray data on protein-DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D124–128. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rowan S, Siggers T, Lachke SA, et al. Precise temporal control of the eye regulatory gene Pax6 via enhancer-binding site affinity. Genes Dev. 2010;24(10):980–985. doi: 10.1101/gad.1890410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siggers T, Gordan R. Protein-DNA binding: complexities and multi-protein codes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(4):2099–2111. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stenson PD, Mort M, Ball EV, et al. The Human Gene Mutation Database: building a comprehensive mutation repository for clinical and molecular genetics, diagnostic testing and personalized genomic medicine. Hum. Genet. 2014;133(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1358-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stormo GD. Modeling the specificity of protein-DNA interactions. Quant Biol. 2013;1(2):115–130. doi: 10.1007/s40484-013-0012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas-Chollier M, Defrance M, Medina-Rivera A, et al. RSAT 2011: regulatory sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Web Server issue):86–91. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomovic A, Oakeley EJ. Position dependencies in transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(8):933–941. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Udalova IA, Mott R, Field D, Kwiatkowski D. Quantitative prediction of NF-kappa B DNA-protein interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99(12):8167–8172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102674699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ward LD, Kellis M. Interpreting noncoding genetic variation in complex traits and human disease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30(11):1095–1106. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weirauch MT, Cote A, Norel R, et al. Evaluation of methods for modeling transcription factor sequence specificity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31(2):126–134. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weirauch MT, Yang A, Albu M, et al. Determination and inference of eukaryotic transcription factor sequence specificity. Cell. 2014;158(6):1431–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao Y, Ruan S, Pandey M, Stormo GD. Improved models for transcription factor binding site identification using nonindependent interactions. Genetics. 2012;191(3):781–790. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.138685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]