Summary

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is known to be associated with the development of malignant lymphoma and lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs) in immunocompromised patients. EBV, a B-lymphotropic gamma-herpesvirus, causes infectious mononucleosis and oral hairy leukoplakia, as well as various pathological types of lymphoid malignancy. Furthermore, EBV is associated with epithelial malignancies such as nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), salivary gland tumor, gastric carcinoma and breast carcinoma. In terms of oral disease, there have been several reports of EBV-related oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) worldwide. However, the role of EBV in tumorigenesis of human oral epithelial or lymphoid tissue is unclear. This review summarizes EBV-related epithelial and non-epithelial tumors or tumor-like lesions of the oral cavity. In addition, we describe EBV latent genes and their expression in normal epithelium, inflamed gingiva, epithelial dysplasia and SCC, as well as considering LPDs (MTX- and age-related) and DLBCLs of the oral cavity.

Keywords: Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), MTX- and age-related EBV + B-cell LPD, Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), Early growth transcription response-1 (Egr-1)

1. Introduction

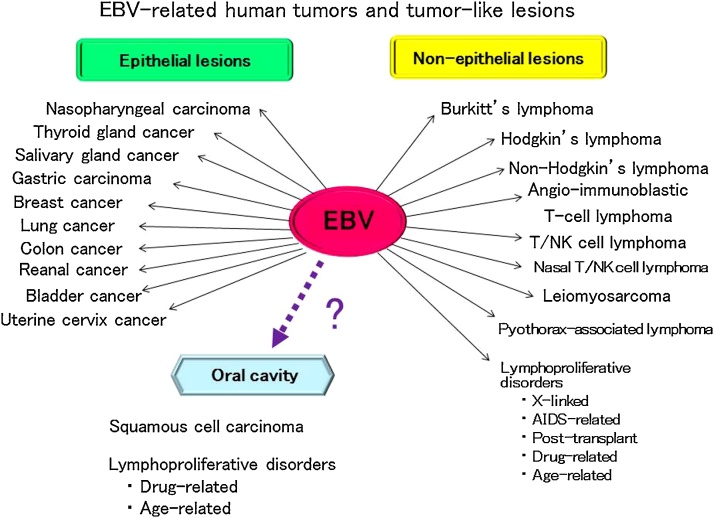

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) was first isolated by Epstein et al. [1] in 1964 from cultured cells of Burkitt’s lymphoma frequently found in children of equatorial Africa. EBV, human herpes virus-4 (HHV-4), is classified as one of the γ herpes subfamily of the HHVs [2]. It is a double-stranded DNA virus of about 170 kb, and encodes about 80 genes. EBV-determined nuclear antigen-1 (EBNA-1) is required for self-replication of the virus [3], [4], [5], and EBNA-2 and latent infection membrane protein-1 (LMP-1) are associated with immortalization of infectious cells in vitro [6], [7], [8]. EBV occurs almost universally, and about 90–95% of adults throughout the world become infected, usually in childhood or early adolescence [9], [10]. The oral cavity and pharyngolarynx is the main portal through which environmental pathogenes enter the human body. The oral cavity is located close to Waldeyer’s ring, which is rich in lymphoid tissue. Although EBV has been known to infect B cells of the pharyngeal tonsils via saliva, it has been shown that EBV also infects other cell types, including epithelial cells [2], [11]. Despite the close association of EBV with a range of lymphoid and epithelial malignancies, the virus does not cause major symptoms in the majority of lifelong carriers with EBV-infected memory B lymphocytes [12], [13]. The role of EBV in transformation in human malignancies remains unclear, particularly in epithelial cancer. EBV gene expression alters the biological properties of the infected cells in both latent and lytic infections, and may result in the development of cancer in humans [14]. EBV is associated with a variety of malignant lymphomas, such as Burkitt’s, Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in immunodeficiency, and lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the parotid gland, as well as epithelial malignancy of the thyroid, lung, nasopharynx, and stomach [10], [15], [16], [17], [18] (Fig. 1). Moreover, EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disorders (EBV-LPDs) are known to occur through EBV reactivation due to decreased immunity of the host in situations such as infectious diseases [19], organ transplantation [20], drug use [21] and aging [22]. In fact, we have previously reported EBV-associated B-cell LPDs arising in the oral cavity [23], [24]. Various EBV-associated epithelial carcinomas such as those of the nasopharynx [25], stomach [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], salivary gland [33], [34], [35], breast [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], bladder [44], kidney [45], uterine cervix [46], colon [47], and lung [48] have been described. Most oral carcinomas are squamous cell carcinomas that originate from outgrowth of the mucosal epithelium. The reported rate of positivity for latent EBV genes in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) has varied from 15% to 70% [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59]. Although there have been many reports on the association of EBV with OSCCs or LPDs in the oral cavity, the role of EBV in carcinogenesis and cancer development remains unclear. The recently reported EBV-associated epithelial and non-epithelial malignancies, OSCCs and LPDs, are herein reviewed.

Figure 1.

Human tumor associated EBV is related to a wide range of human epithelial and non-epithelial malignancies.

2. Interaction of EBV with host cell surface receptors and cell entry

Cell entry is a fundamental part of the infectivity process for any virus, and cell surface receptors are the critical molecules for target cell recognition determining cell tropism and species specificity [60], [61], [62] (Table 1). The EBV double-stranded linear DNA genome is packed inside a capsid which is surrounded by a tegument. This is further enclosed by a lipid envelope consisting of several conserved glycoproteins. These glycoproteins play important roles during initial attachment and subsequent viral entry through interaction with specific host cell surface receptors mediating micropinocytosis [62], [63] and lipid raft-dependent endocytosis [62], [63], [64]. The initial phase of EBV attachment to the cell surface of B cells occur via the viral envelope glycoprotein gp350/gp220, which interacts with the cellular receptor CD21 [65], and also with CD35 as an alternative EBV attachment receptor in certain CD21-negative cells [66]. EBV glycoprotein gp350 (or gp220) binds to CD21 (or CD35) inducing endocytosis, and the EBV is then captured by the B cell [67]. Interaction with B lymphocyte virus glycoprotein gB and a 3-part complex of glycoproteins, gH/gL/gp42, and human leukocyte antigen class II (HLA class II) eventually triggers fusion of the virus with the endosomal membrane, allowing entry of the tegumented capsid into the cytoplasm [68]. On the other hand, in epithelial cells, direct interaction between EBV gH/gL and integrins ɑvβ6 and ɑvβ8 can provide the trigger for fusion of EBV with an epithelial cell [69]. In addition, the EBV transmembrane envelope glycoprotein BMRF2 has been shown to interact with intwgrins β1 and ɑ5 on oral epithelial cells, but not on B cells [70], [71]. Recently it has been reported that in nasopharyngeal epithelial cells, neuropilin 1 (NRP1) interacts with EBV gB and promotes EBV infection of epithelial cells by coordinating the receptor tyrosin kinase (RTK) signaling pathway and macropinocytic events [72].

Table 1.

EBV glycoproteins and host cell surface receptors.

| Infected cell types of EBV | EBV glycoproteins [Gene name] | Role in virus entry | Attachment receptors/uptake or co-receptor | Uptake mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B cells | gp350 [BLLF1] | Attachment to B-cell | CD21 (CR2) CD35(CR1) |

Macropinocytosis and lipid raft-dependent endocytosis |

| gp42 [BZLF] | Attachment to B-cell |

HLA class II |

||

| Membrane fusion | ||||

| gp25 (gL) [BKRF2] | Chaperon for gH | Unknown | ||

| gp110 (gB) [BALF4] | Membrane fusion | Unknown | ||

| epithelial cells (oropharyngial) | gp85 (gH) (BDLF3) | Attachment to epithelial cells | Integrin β1, ɑ5 | Lipid raft-dependent endocytosis |

| Membrane fusion | ||||

| BMRF2 (BMRF2) | Attachment to epithelial cells | Integrin ɑvβ6, ɑvβ8 | ||

| gp25 (gL) [BKRF2] | Chaperon for gH | Unknown | ||

| gp110 (gB) [BALF4] | Membrane fusion | NRP1 |

3. Gene expression patterns in EBV latency

EBV shows primary tropism for B cells and epithelial cells, but can also infect NK, T and smooth muscle cells, with the ability to cause oncogenesis in all of these cell types [73]. EBV infection in epithelial cells exhibits an expression program distinct from that of B cells [74], [75]. EBV infection of primary B cells initiates a robust growth and proliferation program in which type III latency genes are expressed, including non-coding RNAs (EBV-encoded small RNA: EBERs), six nuclear proteins (EBNA1, 2, 3A, 3B, 3C and EBNA-LP) and three membrane proteins (LMP-1, 2A and 2B) [76]. In contrast, EBV infection dose not induce clonal expression in primary epithelial cells [77]. EBNA-LP, EBNA2 and EBNA3C, which play a crucial role in B cell immortalization and cell cycle progression, are not expressed in infected epithelial cells. A more restricted group of latent genes (type II latency) are expressed, including EBNA1, LMP1, LMP2A and EBERs [12], [77], [78], [79]. Notably, high level of BamHI A rightward transcripts (BARTs) are expressed in both nasopharyngeal carcinoma and gastric cancer, suggesting their involvement in epithelial malignancies [79], [80], [81]. EBV has a biphasic life cycle with two stages. The lytic cycle allows EBV to productively infect new cells and new hosts, whereas the latency cycle is vital to allow persistence of the virus within infected cells. Latency can be further divided into four types (Table 2) with restricted viral gene expression to avoid immune surveillance. Viral gene expression changes when EBV enters the lytic cycle [74], [75], [76].

Table 2.

Gene expression pattern in EBV latency.

| Types | EBERs | EBNA1 | LMP1, 2 | EBNA2, 3, LP | Examples (related disease) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latency III | + | + | + | + | Transformed B cells in vitro (lymphoblastoid cell line; LCL) |

| Immunodeficiency-associated lymphoproliferative disorders | |||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Latency II | + | + | + | Hodgkin’s lymphoma | |

| Extranodal T/NK cell lymphoma | |||||

| Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, nasal type | |||||

| Aggressive NK cell leukemia | |||||

| Pyothorax-associated lymphoma | |||||

| Lymphomatoid granulomatosis | |||||

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | |||||

| Latency I | + | + | Burkitt’s lymphoma | ||

| Gastric carcinoma | |||||

| Latency 0 | + | Resting memory B cell (Healthy carriers) | |||

4. Roles of EBV-encoded latent genes in carcinogenesis

The oncogenic capacity and properties of EBV are recognized through its in vitro transforming effects. Following infection of primary human B cells in vitro, EBV induces their proliferation resulting in the development of lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs). The genes of six EBV nucler antigens (EBNA1, 2, 3A, 3B, 3C and EBNA-LP) as well as three latent membrane proteins (LMP-1, 2A and 2B) are expressed in these cells. Likewise, these proteins are expressed in the early phases of natural infection [82], [83]. EBNA2 is regarded as the central transcription factor for both viral and cellular gene expression. It is responsible for B cell proliferation and expressed in LCLs [84]. LMP-1 expression, in turn, is regulated by EBNA2 and serves as an active receptor for tumor necrosis factor (TNF-ɑ), which is essential for apoptosis [85]. LMP-1 has also been reported to signal in the B cell similarly to CD40- CD40 ligand interaction, showing functional properties similar to those of activated CD40 [86]. However, in the absence of EBNA2 in EBV-proliferating B lymphocytes, CD40 activation and LMP1 expression confer a similar phenotypic characteristic, i.e. the continuous survival of the cell [87]. Interestingly, however, both CD40 activation and LMP1 expression also prevent apoptosis of B cells [88], [89]. Additionally, experiments with transgenic mice have revealed that LMP1 mimics CD40 signaling for B-cell differentiation during natural infection [90]. The roles of different EBV-encoded latent genes in tumor formation have been confirmed [91], [92] and these are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

| Latent genes | Role of latent genes |

|---|---|

| EBNA-1 | Transactivator of viral latent genes and host genes; responsible for episome replication, segregation and persistence of viral genome; involved in p53 degradation and oncogenesis. |

| EBNA-LP | Transcriptional co-activator of EBNA-2-dependent viral and cellular gene transcription; It is essential for EBV-mediated B-cell transformation. |

| EBNA-2 | Activates viral and cellular gene transcription for transformation. It is critical for EBV-mediated B-cell transformation. |

| EBNA-3A | A co-activator of EBNA-2, downregulate c-Myc transcription and block EBNA-2 activation effects; and induce CDKN2 and chemokines. It is essential for EBV-mediated B-cell transformation. |

| EBNA-3B | A co-activator of EBNA-2; dispensable for B-cell transformation; viral tumor suppressor; and up regulates CXCL10. EBNA-3B-knockout induces DLBCL-like tumors. |

| EBNA-3C | Co-activaters with EBNA-2 host CXCR4 and CXCL12; overcomes EBV-infection-mediated DNA damage response; promotes cell proliferation; induces G1 arrests; It is essential for EBV-mediated B-cell transformation. |

| LMP-1 | Mimics the consistutively active form of CD40, activates NF-κB, JNK and p38 pathways; is critical for EBV-mediated B-cell transformation, a major EBV-encoded oncogene; activates NF-κB, JNK and p38 pathways; and induces EMT of NPC and acquisition of cancer stem cell-like properties. |

| LMP-2A | Mimics constitutively active, antigen-independent BCR signaling through constitutive activation of the ERK/MAPK pathway224; blocks antigen-dependent BCR signaling; induces B-cell lymphoma in transgenic condition; it is important but not essential for in vitro primary B-lymphocyte growth transformation; rescues the LMP-1-generated impairment in germinal center in the response to antigen in animals; confers resting B cells sensitive to NF-κB inhibition and apoptosis; suppresses differentiation and promots epithelial cell spreading and motility in epithelial cells; and enriches cancer stem cell-like population. |

| EBER | Most abundant EBV-encoded non-coding RNAs; augments colony formation and induces growth; confers cells resistance to PKR-dependent apoptosis; induces cytokines and modulates innate immune response; binds to La, PKR, L22, PRR and RIG-I; and EBER-mediated RIG-I activation likely contributes to EBV oncogenesis. EBER blockades of PKR-mediated phosphorylation of eIF2ɑ results in blockage of eIF2ɑ-mediated inhibition of protein synthesis and resistance to IFNɑ-induced apoptosis. |

| miRNAs | Has a role sustaining latently infected cells. BHRF1 miRNA and BART miRNAs interfere with apoptosis. |

5. Detection of EBV gene and latent infection gene expression in normal epithelia, epithelial dysplasia, and OSCC of the oral cavity

5.1. Detection of EBV genes by PCR

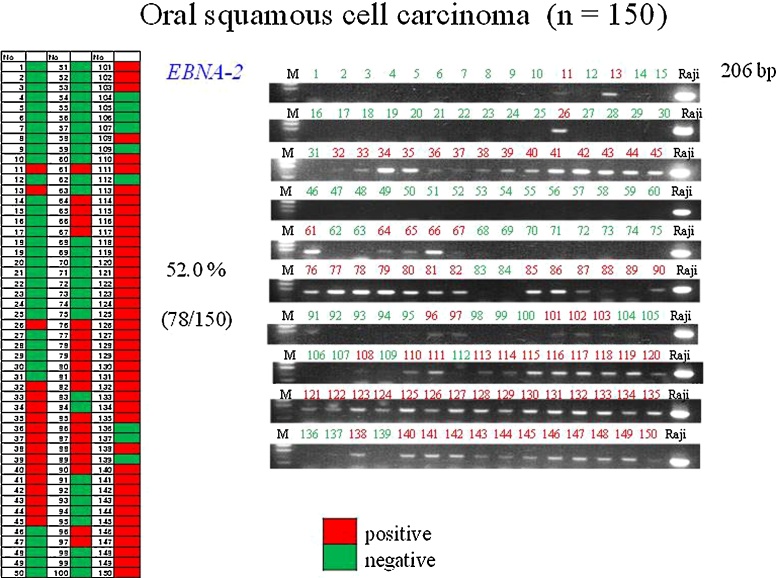

Previous reports have indicated that the average rate of detection of EBNA-2 in OSCC tissue by PCR is about 42.8% [49], [50], [51], [52]. This is similar to the rate (52.0%) we found in 150 cases of OSCC (Fig. 2), but the rate of LMP-1 detection by PCR was low. The rate of detection of EBV genes in OSCC (EBNA-2: 52.0%, LMP-1: 10.7%) tends to be low in comparison with NPC (EBNA-2: 66.7%, LMP-1: 33.3%) [93]. It has been reported that the positivity rate for EBNA-2 and LMP-1 in Japan is 70% in Okinawa (in the south) and 30% in Hokkaido (in the north) [52], [53]. Some authors have reported that LMP-1 is detectable vy PCR in 95.6% of NPC tissues, whereas it was not detectable in OSCC, pharyngeal carcinoma or tonsil tissue [94]. Moreover, Horiuchi et al. have reported that EBV infection in OSCCs was detected in 52.8% of cases by PCR and that EBER was detected 27.5% of cases by in-situ hybridization (ISH), whereas LMP-1 was not detectable [54]. These reports indicated a low level of LMP-1 among the EBV genes in OSCCs. A research group in Thailand has indicated that EBV is not a risk factor for OSCC, as they found that EBER was not detectable in 24 such cases [95]. A more recent PCR study has reported positivity for EBV infection in all of 36 (100%) OSCCs, 7 of 9 (77.8%) pre-cancerous lesions and 1of 12 (8.3%) normal mucosa samples [96]. Furthermore, a research group in Taiwan using EBV genomic microarray (EBV-chip) has reported a high rate of EBV infection (82.5%) in biopsy specimens from 57 cases of OSCC [94]. Using PCR, we have confirmed the presence of EBV latent infection genes in normal epithelia, gingivitis, epithelial dysplasia, and OSCC. The expression of EBV latent infection genes was significantly higher in severe epithelial dysplasia (EBNA-2: 66.7%, LMP-1: 44.4%) than in OSCC (EBNA-2: 52.0%, LMP-1: 10.7%), which is a finding not reported previously. EBV genes were also detectable in normal mucosa (EBNA-2:83.3% and LMP-1:23.3%) and gingivitis (EBNA-2:78.1% and LMP-1:21.9%) [93]. Similarly, it has been reported that the EBV detection rate was 0–7% [49], [55], [56] or 92% [57] in normal oral mucosa, and 19–27% in gingivitis [97], thus supporting our PCR data for non-tumorous lesions. These findings suggest that the oral cavity is an environment that favors latent EBV infection (Figure 3, Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Detection of the EBNA-2 genes in oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCCs) by PCR.

PCR analysis of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) genes in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues.

The detection rate of EBNA-2 (206 bp) in OSCC specimens was 52.0%. Positive and negative cases are marked red and green, respectively. EBNA-2 bands showed the same level as those in Raji cells used as a positive control.

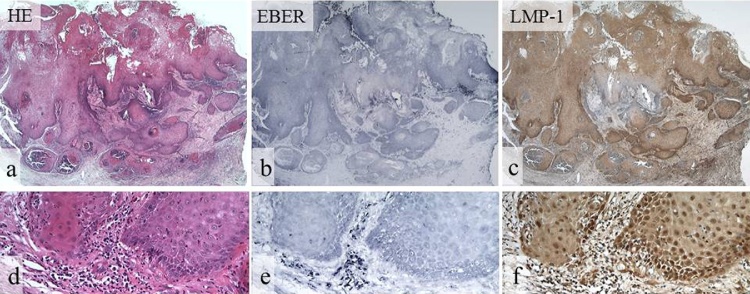

Figure 3.

EBER and LMP-1 expression in OSCCs detected by ISH and IHC.

HE staining (a, d), EBER (b, e), and LMP-1 (c, f). Positive reaction for EBER and LMP-1 shows a similar distribution in OSCC (b, c). Reaction for EBER is weakly positive in SCC, and inflammatory cells are strongly positive in the stroma (e). Reaction for LMP-1 is strongly positive in SCC and inflammatory cells in the stroma (f). (a–c, original magnification, ×12.5, d–f, original magnification, ×200).

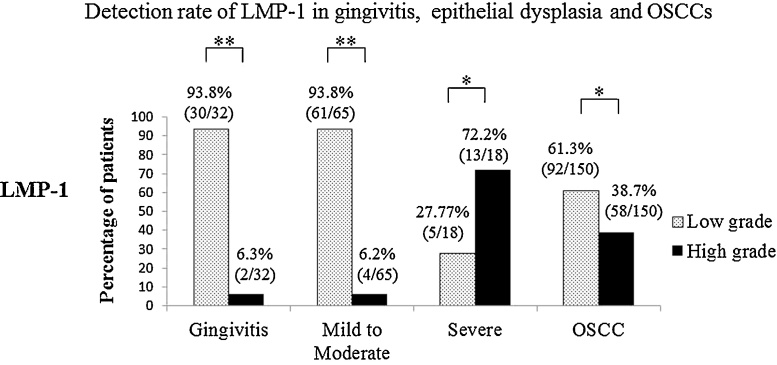

Figure 4.

Expression of LMP-1 in gingivitis, epithelial dysplasia and OSCC.

LMP-1 expression was greater in severe epithelial dysplasia than in inflamed gingiva, mild to moderate epithelial dysplasia and OSCC. P values were determined by Mann–Whitney U test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

5.2. Detection of EBER by in-situ hybridization (ISH)

As EBER is detected in healthy adults with a history of EBV infection, there is a need for caution with evaluation. In EBV-infected cells EBER is localized primarily in the nucleus, but may also be present in the cytoplasm [98]. Therefore, there is a need to evaluate both of these sites. We found a positive reaction for EBER in the nucleus or cytoplasm in each of the lesions we tested. High-grade EBER expression was more evident in NPC (61.9%) than in SCC (34.7%). Here we newly demonstrated that high-grade EBER expression was significantly more frequent in severe epithelial dysplasia (94.4%) than in OSCC (34.7%), mild to moderate epithelial dysplasia (21.5%), and gingivitis (65.6%) [93]. EBER was highly expressed in severe epithelial dysplasia and was related to carcinogenesis in pre-cancerous tissue. Gene expression indicative of EBV infection is considered to be reduced over time after a cancerous change occurs. In Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines, EBV clones become reduced during long-term passage [3].

5.3. Detection of LMP-1 by immunohistochemistry (IHC)

LMP-1 is known to be an oncogene [7], [8] essential for immortalization of B cells developing into B-cell lymphoma in transgenic mice [99], [100]. Furthermore, it has been reported that LMP-1 inhibits the differentiation of human epithelial cells [101], being also related to cancer development, growth, invasion, metastasis and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition [102]. However, there have been few reports of LMP-1 expression in OSCC. Using IHC, Gonzalez-Moles et al. showed that LMP-1 protein was positively expressed in 31 out of 78 (39.7%) OSCCs, 19% of which showed EBV-positivity by PCR [58]. Similarly, Kobayashi et al. found expression of LMP-1 protein in 6 out of 46 (13.0%) OSCCs [51]. In contrast to these reports, Kis et al. [103] and Cruz et al. [104] detected no expression of LMP-1 protein in OSCC. In a recent study, however, high-grade expression of LMP-1 was observed in NPC (52.4%), OSCC (38.7%), severe epithelial dysplasia (72.2%), mild to moderate epithelial dysplasia (6.2%), and gingivitis (6.3%) [93]. Although LMP-1 expression was most commonly seen in NPC, its expression was also significant in OSCC. Of note was that the rate of high-grade LMP-1 expression was higher in severe epithelial dysplasia (72.2%) than in OSCC (38.7%) [93], a new finding that had not been reported previously. It has been reported that LMP-1 expression is related to the activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation (STAT3) [105], [106]. An important role of LMP-1 expression is activation of STAT3, and also the signaling pathway that includes Janus kinase 3 (JAK3)/STAT3, inhibitor of kappa B kinase (IκB kinase: IKK)/nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/activator protein 1 (AP-1), and MAPK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) [106], [107]. Fang et al. have reported that LMP-1 has a double activation mechanism due to an increase in the NPC cell membrane programmed cell death protein 1 ligand (PD-L1), and induction of PD-L1 in the JAK/STAT pathway through the interferon-γ (IFN-γ) receptor by production of IFN-γ from T-cells [107]. Furthermore, Chen et al. have reported that LMP-1 expression increased the levels of STAT3 and c-MYC protein in NPC cell lines [108]. Expression of LMP-1 in oral precancerous lesions and OSCC suggests the involvement of STAT3 activation in the dysplasia-carcinoma sequence in the oral cavity.

6. EBV-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs) of the oral cavity

6.1. MTX- related EBV-associated B cell LPDs

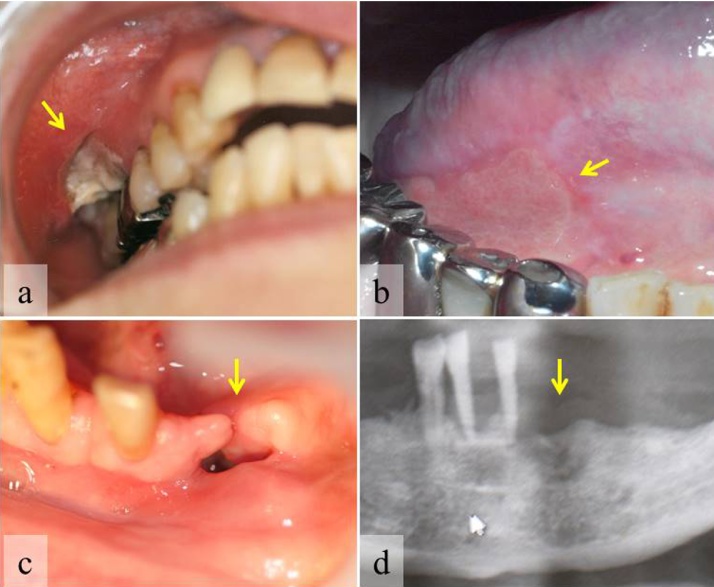

In recent years, reports of EBV-associated B-cell LPD of the oral cavity have increased [23], [24], [109], [110]. EBV associated B-cell LPDs occurring in the oral cavity are often seen as intractable mucosal ulcers (Fig. 5a,b) or as failure of extraction sockets to heal (Fig. 5c,d) [23], [24], [109]. The affected patients are believed to be immunosuppressed, a condition that causes reactivation of EBV. EBV-driven B cell LPDs can be age-related or can occur in patients who are immunosuppressed due to primary immune deficiency, HIV infection, organ transplantation, and treatment with methotrexate (MTX) or tumor necrosis factor-ɑ (TNF-ɑ) antagonist for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [111], [112]. MTX is regarded as an effective immunosuppressive agent for treatment of autoimmune diseases, especially RA, and is therapeutically effective in many cases that are resistant to some anti-rheumatic drugs [113]. Recently, it has been shown that patients with RA and other rheumatic diseases treated with MTX have an increased risk of developing LPDs or lymphomas [114]. Patients with immunodeficiency have a higher risk of LPDs than immunocompetent individuals. Approximately 50% of LPDs are EBV-positive [114]. Overall, approximately 40% of reported cases have involved extranodal sites, including the gastrointestinal tract, skin, lung, kidney, and soft tissues [114], [115], including the oral cavity [23], [109], [110]. Overall, however, approximately 60% of reported cases have shown at least partial regression in response to withdrawal of MTX, the majority being EBV positive cases [114]. The mechanism by which MTX increases the propensity of RA patients for development of lymphomas is not entirely clear. Menke et al. [115] have reported that cell dysregulation as measured by p53 protein expression and EBV-related transformation play important roles in the pathogenesis of lymphomas arising in patients with connective tissue disease who are immunosuppressed with MTX.

Figure 5.

Intractable mucosal ulcers or healing failure of extraction sockets.

Buccal ulcer (a) and ongue ulcer (b) in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with MTX. Failure of gingival mucosa (c) and bone (d) healing in a senile patient after tooth extraction [24].

6.2. Age-related EBV-associated B cell LPDs

Age-related EBV-associated B cell LPD is a group of clinicopathologic entities, originally described by Oyama et al. [116], that differs from immunodeficiency-associated LPDs in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification [117], occurring predominantly in elderly patients over the age of 50 years (median age 71 years) and sharing features of EBV-positive B cell neoplasms seen in patients with immunologic impairment despite absence of any predisposing immunodeficiency [116], [118]. Age-related EBV positive B cell LPD may be associated with immune senescence in the elderly, and is now incorporated into the 2008 WHO lymphoma classification as EBV-positive diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) of the elderly [119]. Approximately 70% of reported cases of this newly described disease have involved extranodal sites, such as the skin, lung, tonsil and stomach [119], and been characterized by proliferation of atypical large B cells including Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg-like cells with reactive inflammatory components. Age-related EBV-associated B cell LPD is rare in the oral cavity [24] (Fig. 5c, d).

6.3. Roles of LMP-1 protein in B cell lymphomagenesis

The products of viral genes upregulate a variety of cellular antigens and expression of genes in B cells. Key molecular pathways controlling the cell cycle, such as nuclear factor-kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B-cells (NF-κB), are activated and virus-induced cytokines exert paracrine proliferative effects [12], [120], [121], [122]. The major EBV-encoded LMP-1 is an integral membrane protein, which activates signaling pathways such as that involving NF-κB, which increases B-cell survival and facilitates transformation [85], [123], [124], [125], [126] by induction of anti-apoptotic protein. LMP-1 is a 63-kDa integral membrane protein with three domains, and contains two distinct functional regions within its C-terminus, designated C-terminal activating regions 1 and 2 (CTAR1 and CTAR2). The protein also protects cancer cells from apoptosis, by inducing anti-apoptotic proteins, including BCL-2, MCL-1, A20, early growth response transcription factor-1(Egr-1) and SNARK [127], [128], [129]. An in vitro study has shown that EBV-infected cells undergo hypermutation or switching of recombination via up-regulation of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) [130], and EBV-induced AID is also associated with oncogene mutations that contribute to lymphomagenesis [131]. In a mouse bone marrow transplantation model, AID overexpression was reported to promote B-cell lymphomagenesis [132]. Although the relationship between LMP-1 and lymphomagenesis has been relatively well established, the molecular mechanisms underlying AID induction remain to be fully clarified.

6.4. Roles of AID in B-cell lymphomagenesis

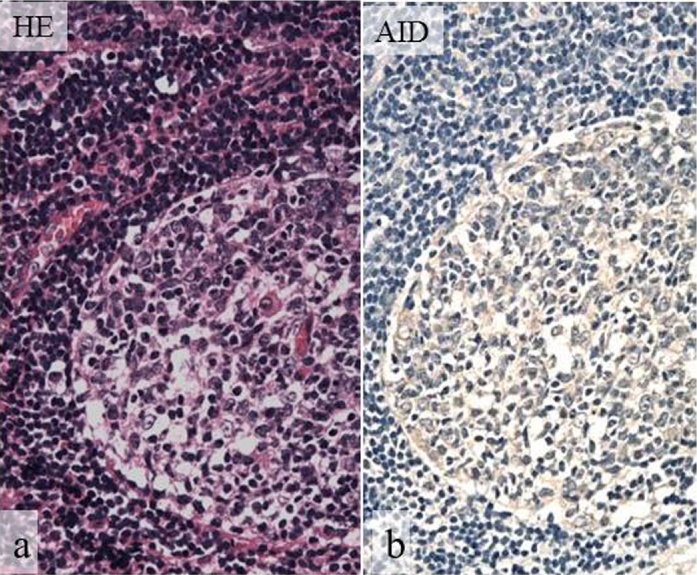

Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) is normally expressed in germinal center (GC) B-cells [110], [133] (Fig. 6), where it plays a central role in both somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination in humans and mice [134], [135]. AID converts single-stranded genomic cytidine to uracil, with pronounced activity in the immunoglobulin variable and switch regions [136], [137], [138], [139]. Aberrant expression of AID and abnormal targeting of AID activation in both B- and non-B-cells causes DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) and DNA point mutations in both Ig and non-Ig genes, inducing tumorigenesis [140]. AID is required for chromosomal DSBs at the c-myc and IgH loci, leading to reciprocal c-myc/IgH translocations and resulting in the development of B-cell lymphomas, such as Burkitt lymphoma in humans and plasmacytoma in mice [141]. AID protein is localized more in the cytoplasm than in the nucleus in normal and neoplastic B-cells, and cytoplasmic AID protein relocates to the nucleus when pathological change occurs in B-cells [142], [143]. A recent in vitro study by Kim et al. [144] has shown that LMP-1 increases genomic instability through Egr-1-mediated up regulation of AID in B-cell lymphoma cell lines.

Figure 6.

Normal expression of AID in lymphoid tissue.

HE staining (a), AID (b). Normal expression of AID is evident in germinal centers of lymph nodes with reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. (a, b, original magnification, ×100).

6.5. Roles of Egr-1 in B-cell lymphomagenesis

The early growth transcription response-1 (Egr-1) gene (also named zif268, NGFI-A, or Krox24) encodes an 80-kDa DNA-binding transcription factor [145]. Egr-1 is an exceptionally multi-functional transcription factor. In response to growth factors and cytokine signaling, Egr-1 regulates cell growth, differentiation and apoptosis [146]. Egr-1 has been associated with EBV infection [147]. First, Egr-1 is upregulated when EBV interacts with B lymphocytes at the initial infection stage, and constitutive expression of Egr-1 correlates with certain types of EBV latency in B-lymphoid cell lines [148]. EBV reactivation is associated with up-regulation of Egr-1, and Egr-1 can be induced as an EBV lytic transactivator [149].

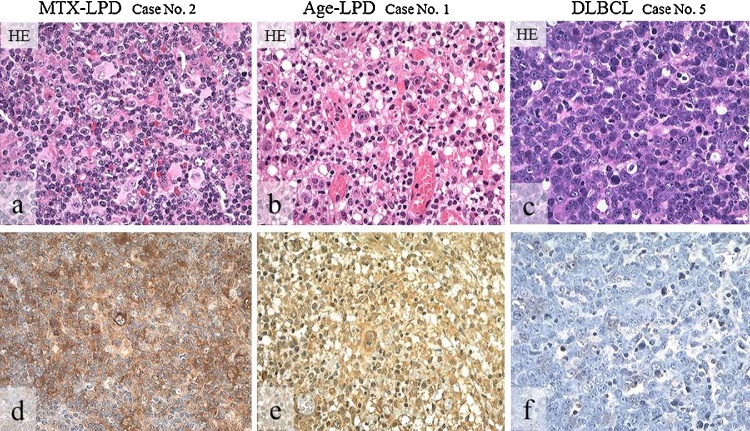

6.6. Comparison of DLBCLs with MTX- and age-related EBV-associated B-cell LPDs

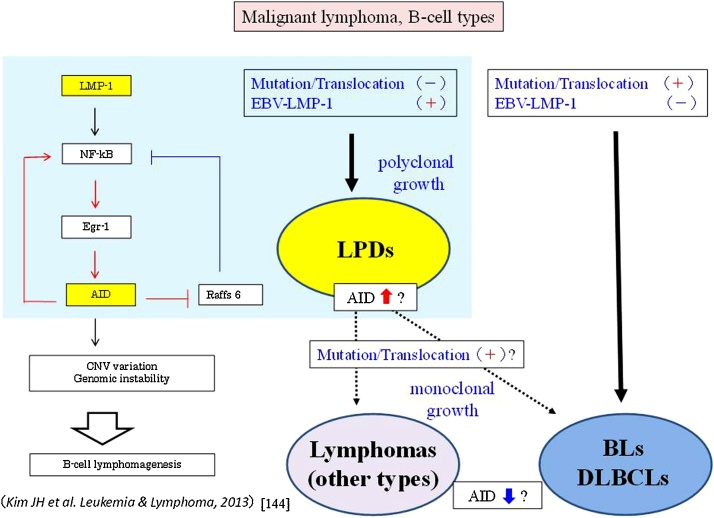

AID triggers somatic hypermutation and recombination, in turn contributing to lymphomagenesis. Such aberrant AID expression is seen in B-cell leukemia/lymphomas, including Burkitt lymphoma which is associated with c-myc translocation. Moreover, LMP-1 increases genomic instability through Egr-1 mediated upregulation of AID in B-cell lymphoma. We conducted an immunohistochemical study to investigate the relationship between AID and LMP-1 expression in 19 cases of LPD (MTX-/age-related EBV-associated), including 10 cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL) [110]. Immunoreactivity for AID was stronger in LPDs than in DLBCLs (Fig. 7). More intense AID expression was detected in LPDs (89.5%) than in DLBCLs (20.0%), and the expression of LMP-1 and EBER was more intense in LPDs (68.4% and 94.7%) than in DLBCLs (10.0% and 20.0%) [110]. Furthermore, stronger Egr-1 expression was found in MTX/age-related EBV-associated LPDs (83.3%) than in DLBCLs (30.0%). AID expression was significantly and constitutively overexpressed in LPDs relative to DLBCLs. These results suggest that increased AID expression in LPDs may be one of the processes involved in lymphomagenesis, thereby further increasing the survival of genetically destabilized B-cells (Fig. 8). AID expression may be a useful indicator for differentiation between LPDs and DLBCLs.

Figure 7.

Distribution and intensity of AID expression in biopsy specimens of MTX-/age-related EBV-LPDs and DLBCLs.

HE stain (a–c), and AID (d–f) detected by IHC (brownish color). AID-positive atypical lymphoid cells show diffuse in MTX-LPD (d) and age-related LPD (e), but are few in DLBCL (f). AID positive cells show strong intensity in MTX-LPD (d) and Age-related LPD (e), and weak or moderate intensity in DLBCL (f). (a–f, original magnification, ×200).

Figure 8.

A recent in vitro study by Kim et al. [144] has shown that LMP-1 increases genomic instability through Egr-1-mediated upregulation of AID in B-cell lymphoma cell lines. A recent in vivo study [110] has demonstrated overexpression of AID, including LMP-1 and Egr-1, in LPDs (MTX- and age- related) associated with pre-cancerous states due to immunosuppression in the head and neck. In LPDs that occur in patients who are immunosuppressed due to MTX administration or ageing, memory B-cells without mutation/translocation first express LMP-1 by reactivation of EBV latent genes. Secondly, LPDs with polyclonal growth show an increase AID expression through the LMP-1/NF-kB/Egr-1 signaling pathway, and LPDs with monoclonal proliferation undergo gene mutation or gene translocation throuugh the effect of increased AID. Abnormal long-term expression of AID in LPDs leads to development of true malignant lymphoma, and the changed malignant B-cell lymphomas show an increase of AID expression through acquired monoclonal growth. On the other hand, lymphoma caused by a gene mutation will develop when the expression of AID is absent or low involved.

7. Conclusion

EBV infection is relate to cancers of lymphoid and epithelial tissues such as Burkitt’s lymphoma, Hodgkin’s disease, NPC, gastric carcinoma and OSCC. However, it has remained uncertain whether EBV plays a role in lymphomagenesis and carcinogenesis of the oral cavity. Using PCR and ISH, we have found that EBV latent genes are present in B-cell-type lesions (LPDs) as well as in oral epithelial lesions (inflamed gingiva, severe epithelial dysplasia and OSCC). In particular, it was suggested that LMP-1 expression may play an important role in lymphomagenesis and carcinogenesis in the oral cavity. In the dysplasia-carcinoma sequence, LMP-1 expression was mostly higher in severe epithelial dysplasia than in OSCC. In LPDs, expression of LMP-1, Egr-1 and AID was higher than in DLBCLs. Both LPDs and severe epithelial dysplasia are considered to be precancerous conditions. Increased AID expression in LPDs of the oral cavity may be part of the process of lymphomagenesis, thereby further increasing the survival of genetically destabilized B-cells. Likewise, the LMP-1/Egr-1/AID signaling pathway may be related to the dysplasia-carcinoma sequence in the oral cavity. Further study is needed to clarify the role of EBV latent genes and their reactivation mechanisms for malignant transformation in oral disease.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest associated with this review.

Acknowledgements

Part of this work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) No. 25463118.

References

- 1.Epstein M.A., Achong B.G., Barr Y.M. Virus particles in cultured lymphoblasts from Burkitt’s lymphoma. Lancet. 1964;1:702–703. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(64)91524-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okano M., Gross T.G. Advanced therapeutic and prophylactic strategies for Epstein–Barr virus infection in immunocompromised patients. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2007;5:403–413. doi: 10.1586/14787210.5.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimizu N., Tanabe-Tochikura A., Kuroiwa Y., Takada K. Isolation of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-negative cell clones from the EBV-positive Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) line Akata: malignant phenotypes of BL cells are dependent on EBV. J Virol. 1994;68:6069–6073. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6069-6073.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yates J.L., Warren N., Sugden B. Stable replication of plasmids derived from Epstein–Barr virus in various mammalian cells. Nature. 1985;313:812–815. doi: 10.1038/313812a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shirakata M., Imadome K.I., Hirai K. Requirement of replication licensing for the dyad symmetry element-dependent replication of the Epstein–Barr virus oriP minichromosome. Virology. 1999;263:42–54. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang F., Gregory C.D., Rowe M., Rickinson A.B., Wang D., Birkenbach M. Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 specifically induces expression of the B-cell activation antigen CD23. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:3452–3456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D., Leibowitz D., Kieff E. An EBV membrane protein expressed in immortalized lymphocytes transforms established rodentcells. Cell. 1985;43:831–840. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang D., Liebowitz D., Wang F., Gregory C., Rickinson A., Larson R. Epstein–Barr virus latent infection membrane protein alters the human B-lymphocyte phenotype: deletion of the amino terminus abolishes activity. J Virol. 1988;62:4173–4184. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.11.4173-4184.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luzuriaqa K., Sullivan J.L. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1993–2000. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1001116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houldcroft C.J., Kellam P. Host genetics of Epstein–Barr virus infection, latency and disease. Rev Med Virol. 2015;25:71–84. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paydas S., Ergin M., Erdogan S., Seydaoglu G. Prognostic significance of EBV-LMP1 and VEGF—a expressions in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Leuk Res. 2008;32:1424–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yong L.S., Rickinson A.B. Epstein–Barr virus: 40 years on. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:757–768. doi: 10.1038/nrc1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vockerodt M., Yap L.-F., Shannon-Lowe C., Curley H., Wei W., Vizalikova K. The Epstein–Barr virus and the pathogenesis of lymphoma. J Pathol. 2015;235:312–322. doi: 10.1002/path.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsao S.W., Tsang C.M., Pang P.S., Zhang G., Chen H., Lo K.W. The biology of EBV infection in human epithelial cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012;22:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J., Mookerjee B., Wagner J., Flomenberg N. In vitro methods for generating highly purified EBV associated tumor antigen-specific T cells by using solid phase T cell selection system for immunotherapy. J Immunol Methods. 2007;328:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young L.S., Rowe M. Epstein–Barr virus, lymphomas and Hodgikin’s disease. Semin Cancer Biol. 1992;3:273–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ambinder R.F., Mann R.B. Detection and characterization of Epstein–Barr virus in clinical specimens. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:239–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jha H.C., Banerjiee S., Robertson E.S. The role of gammaherpesviruses in cancer pathogenesis. Pathogenes. 2016;5(18):1–43. doi: 10.3390/pathogens5010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raphaël M., Said J., Borisch B., Cesarman E., Harris N.L. Lymphomas associated with HIV infection. In: Swerdlow S.H., Campo E., Harris N.L., Jaff E.S., Pileri S.A., Stein H., Thiele J., Vardiman J.W., editors. WHO classification of tumors of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. IARC; Lyon: 2008. pp. 340–342. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swerdlow S.H., Webber S.A., Chadburn A., Ferry J.A. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders. In: Swerdlow S.H., Campo E., Harris N.L., Jaff E.S., Pileri S.A., Stein H., Thiele J., Vardiman J.W., editors. WHO classification of tumors of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. IARC; Lyon: 2008. pp. 343–349. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaulard P., Swerdlow S.H., Harris N.L., Jaffe E.S., Sundström C. Other iatrogenic immunodeficiency-associated lymphoproliferative disorders. In: Swerdlow S.H., Campo E., Harris N.L., Jaff E.S., Pileri S.A., Stein H., Thiele J., Vardiman J.W., editors. WHO classification of tumors of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. IARC; Lyon: 2008. pp. 350–351. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura S., Jaffe E.S., Swerdlow S.H. EBV positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly. In: Swerdlow S.H., Campo E., Harris L.N., Jaff E.S., Pileri S.A., Stein H., Thiele J., Vardiman J.W., editors. WHO classification of tumors of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. IARC; Lyon: 2008. pp. 243–244. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kikuchi K., Miyazaki Y., Tanaka A., Shigematu H., Kojima M., Sakashita H. Methotrexate-related Epstein–Barr Virus (EBV)-associated lymphoproliferative disorder–so-called Hodgkin-like lesion–of the oral cavity in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Head Neck Pathol. 2010;4:305–311. doi: 10.1007/s12105-010-0202-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kikuchi K., Fukunaga S., Inoue H., Miyazaki Y., Kojima M., Ide F. A case of age-related Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-associated B cell lymphoproliferative disorder, so-called polymorphous subtype, of the mandible, with a review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7:178–187. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0392-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan J.K.C., Bray F., McCarron P., Foo W., Lee A.W.M., Yip T. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. In: Barnes L., Eveson J.W., Reichart P., Sidransky D., editors. WHO classification of tumors, pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. IARC; Lyon: 2005. pp. 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burke A.P., Yen T.S., Shekitka K.M., Sobin L.H. Lymphoepithelial carcinoma of the stomach with Epstein–Barr virus demonstrated by polymerase chain reaction. Mod Pathol. 1990;3:377–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shibata D., Weiss L.M. Epstein–Barr virus-associated gastric adenocarcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:769–774. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tokunaga M., Land C.E., Uemura Y., Tokudome T., Tanaka S., Sato E. Epstein–Barr virus in gastric carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:1250–1254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imai S., Koizumi S., Sugiura M., Tokunaga M., Uemura Y., Yamamoto N. Gastric carcinoma: monoclonal epithelial malignant cells expressing Epstein–Barr virus latent infection protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:9131–9135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fukayama M., Hayashi Y., Iwasaki Y., Chong J., Ooba T., Takizawa T. Epstein–Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma and Epstein–Barr virus infection of the stomach. Lab Investig. 1994;71:73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iizasa H., Nanbo A., Nishikawa J., Jinushi M., Yoshiyama H. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-associated gastric carcinoma. Viruses. 2012;4:3420–3436. doi: 10.3390/v4123420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishikawa J., Yoshiyama H., Iizasa H., Kanehiro Y., Nakamura M., Nishimura J. Epstein–Barr virus in gastric carcinoma. Cancers. 2014;6:2259–2274. doi: 10.3390/cancers6042259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamilton-Dutoit S.J., Hamilton-Therkildsen M., Nielsen N.H., Jensen H., Hensen J.P.H., Pallesen G. Undifferentiated carcinoma of the salivary gland in Greenland Eskimos: demonstration of Epstein–Barr virus DNA by in situ hybridization. Hum Pathol. 1991;22:811–815. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(91)90210-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kotsianti A., Costopoulos J., Morgello S., Papadimitriou C. Undifferentiated carcinoma of the parotid gland in a white patient: detection of Epstein–Barr virus by in situ hybridization. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:87–90. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herbst H., Niedobitek G. Sporadic EBV-associated lymphoepithelial salivary gland carcinoma with EBV-positive low-grade myoepithelial component. Virchows Arch. 2006;448:648–654. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-0109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Labrecque L.G., Barnes D.M., Fentiman I.S., Griffin B.E. Epstein–Barr virus in epithelial cell tumors: a breast carcinoma study. Carcinoma Res. 2001;55:39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fawzy S., Sallam M., Awad N.M. Detection of Epstein–Barr virus in breast carcinoma in Egyptian women. Clin Biochem. 2008;41:486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arbach H., Viglasky V., Lefeu F., Guinebretière J.M., Ramirez V., Bride N. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) genome and expression in breast carcinoma tissue: effect of EBV infection of breast carcinoma cells on resistance to paclitaxel (Taxol) J Virol. 2006;80:845–853. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.845-853.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Preciado M.V., Chabay P.A., De Matteo E.N., Gonzalez P., Grinstein S., Actis A. Epstein–Barr virus in breast carcinoma in Argentina. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:377–381. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-377-EVIBCI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khabaz M.N. Association of Epstein–Barr virus infection and breast carcinoma. Arch Med Sci. 2013;30:745–751. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.37274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perrigoue J.G., den Boon J.A., Friedl A., Newton M.A., Ahlquist P., Sugden B. Lack of association between EBV and breast carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2005;14:809–814. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herrmann K., Niedobitek G. Lack of evidence for an association of Epstein–Barr virus infection with breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res. 2003;5:13–17. doi: 10.1186/bcr561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deshpande C.G., Badve S., Kidwai N., Longnecker R. Lack of expression of the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) gene products, EBERs, EBNA1, LMP1, and LMP2A, in breast cancer cells. Lab Investig. 2002;82:1193–1199. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000029150.90532.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gazzaniga P., Vercillo R., Gradilone A., Silvestri I., Gandini O., Napolitano M. Prevalence of papillomavirus, Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus type 2 in urinary bladder cancer. J Med Virol. 1998;55:262–267. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199808)55:4<262::aid-jmv2>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimakage M., Kawahara K., Harada S., Sasagawa T., Shinka T., Oka T. Expression of Epstein–Barr virus in renal cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2007;18:41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sasagawa T., Shimakage M., Nakamura M., Sakaike J., Ishikawa H., Inoue M. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) genes expression in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive cervical cancer: a comparative study with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:318–326. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(00)80245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu H.X., Ding Y.Q., Sun Y.O., Liang L., Yang Y.F., Qi Z.L. Detection of Epstein–Barr virus in human colorectal cancer by in situ hybridazition. Di Yi Jun Yi Da Xue Xue Bao. 2002;22:915–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Castro C.Y., Ostrowski M.L., Barrios R., Green L.K., Popper H.H., Powell S. Relationship between Epstein–Barr virus and lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung: a clinicopathologic study of 6 cases and review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:863–872. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.26457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.D’Costa J., Saranath D., Sanghvi V., Mehta A.R. Epstein–Barr virus in tobacco-induced oral cancers and oral lesions in patients from India. J Oral Pathol Med. 1998;27:78–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1998.tb02098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.González-Moles M., Gutiérrez J., Ruiz I., Fernández J.A., Rodriguez M., Aneiros J. Epstein–Barr virus and oral squamous cell carcinoma in patients without HIV infection: viral detection by polymerase chain reaction. Microbios. 1998;96:23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kobayashi I., Shima K., Saito I., Kiyoshima T., Matsuo K., Ozeki S. Prevalence of Epstein–Barr virus in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Pathol. 1999;189:34–39. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<34::AID-PATH391>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsuhako K., Nakazato I., Miyagi J., Iwamasa T., Arasaki A., Hiratsuka H. Comparative study of oral squamous cell carcinoma in Okinawa, Southern Japan and Sapporo in Hokkaido, Northern Japan; with special reference to human papillomavirus and Epstein–Barr virus infection. J Oral Pathol Med. 2000;29:70–79. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2000.290204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Higa M., Kinjo T., Kamiyama K., Chinen K., Iwamasa T., Arasaki A. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-related oral squamous cell carcinoma in Okinawa, a subtropical island, in southern Japan-simultaneously infected with human papillomavirus (HPV) Oral Oncol. 2003;39:405–414. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(02)00164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Horiuchi K., Mishima K., Ichijima K., Sugimura M., Ishida T., Kirita T. Epstein–Barr virus in the proliferative diseases of squamous epithelium in the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79:57–63. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sand L.P., Jalouli J., Larsson P.A., Hirsch J.M. Prevalence of Epstein–Barr virus in oral squamous cell carcinoma, oral lichen planus, and normal oral mucosa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:586–592. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.124462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bagan J.V., Jiménez Y., Murillo J., Poveda R., Díaz J.M., Gavaldá C. Epstein–Barr virus in oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and squamous cell carcinoma: a preliminary study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:110–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jang H.S., Cho J.O., Yoon C.Y., Kim H.J., Park J.C. Demonstration of Epstein–Barr virus in odontogenic and nonodontogenic tumors by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30:603–610. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.301005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gonzalez-Moles M.A., Gutierrez J., Rodriguez M.J., Ruiz-Avila I., Rodriguez-Archilla A. Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 (LMP-1) expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:482–487. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200203000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shimakage M., Horii K., Tempaku A., Kakudo K., Shirasaka T., Sasagawa T. Association of Epstein–Barr virus with oral cancers. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:608–614. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.129786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marsh M., Helenius A. Virus entry. Cell. 2006;124:729–740. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sieczkarski A.B., Whittaker G.R. Viral entry. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;280:1–23. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26764-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sxhäfer G., Blumenthal M.J., Katz A.A. Interaction of human tumor virus with host cell surface receptors and cell entry. Viruses. 2015;7:2592–2617. doi: 10.3390/v7052592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang H.B., Zhang H., Zhang J.P., Li Y., Zhao B., Feng G.K. Neuropilolin 1 is an entry factor that promotes EBV infection of nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6240. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Katzman R.B., Longnecker R. Cholesterol-dependent infection of Burkitt’s lymphoma cell lines by Epstein–Barr virus. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:2987–2992. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fingeroth J.D., Weis J.J., Tedder T.F., Strominger J.L., Biro P.A., Fearon D.T. Epstein–Barr virus receptor of human B lymphocytes is the C3d receptor CR2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:4510–4514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.14.4510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ogembo J.G., Kannan L., Ghiran I., Nicholson-Weller A., Finberg R.W., Tsokos G.C. Human complement receptor type 1/CD35 is an Epstein–Barr virus receptor. Cell Rep. 2013;3:371–385. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tanner J., Weis J., Fearon D., Whang Y., Kieff E. Epstein–Barr virus gp350/220 binding to the B lymphocyte C3d receptor mediates adsorption, capping, and endocytosis. Cell. 1987;50:203–213. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li Q., Spriggs M.K., Kovats S., Turk S.M., Comeau M.R., Nepom B. Epstein–Barr virus uses HLA class II as a cofactor for infection of B lymphocytes. J Virol. 1997;71:4657–4662. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4657-4662.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chesnokova L.S., Nishimura S.L., Hutt-Fletcher L.M. Fusion of epithelial cells by Epstein–Barr virus proteins is triggered by binding of viral glycoproteins gHgL to integrins ɑvβ6 and ɑvβ8. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20464–20469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907508106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xiao J., Palefsky J.M., Herrera R., Berline J., Tugizov S.M. The Epstein–Barr virus BMRF-2 protein facilitates virus attachment to oral epithelial cells. Virology. 2008;370:430–442. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xiao J., Palefsky J.M., Herrera R., Berline J., Tugizov S.M. EBV BMRF-2 facilitates cell-to cell spread of virus within polarized oral epithelial cells. Virology. 2009;388:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang H.B., Zhang H., Zhang J.P., Li Y., Zhao B., Feng G.K. Neuropilin 1 is an entry factor that promotes EBV infection of nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6240. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hutt-Fletcher L.M. Epstein–Barr virus entry. J Virol. 2007;81:7825–7832. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00445-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vockerodt M., Yap L.F., Shannon-Lowe C., Curley H., Wei W., Vrzalikova K. The Epstein–Barr virus and pathogenesis of lymphoma. J Pathol. 2015;235:312–322. doi: 10.1002/path.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tsao S.W., Tsang C.M., To K.F., Lo K.W. The role of Epstein–Barr virus in epithelial malignancies. J Pathol. 2015;235:323–333. doi: 10.1002/path.4448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Houldcroft C.J., Kellam P. Host genetics of Epstein–Barr virus infection, latency and disease. Rev Med Virol. 2015;25:71–84. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tsao S.W., Tsang C.M., Pang P.S., Zhang G., Chen H., Lo K.W. The biology of EBV infection in human epithelial cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012;22:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tsang C.M., Zhang G., Seto E., Takada K., Deng W., Yip Y.L. Epstein–Barr virus infection in immortalized nasopharyngeal epithelial cells: regulation of infection and phenotypic characterization. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:1570–1583. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marquitz A.R., Mathur A., Chugh P.E., Dittmer D.P., Raab-Traub N. Expression profile of microRNAs in Epstein–Barr virus-infected AGS gastric carcinoma cells. J Virol. 2014;88:1389–1393. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02662-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Strong M.J., Xu G., Coco J., Baribault C., Vinay D.S., Lacey M.R. Differences in gastric carcinoma microenvironment stratify according to EBV infection intensity: implications for possible immune adjuvant therapy. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003341. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lung R.W., Tong J.H., To K.F. Emerging roles of small Epstein–Barr virus-derived non-coding RNAs in epithelial malignancy. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:17378–17409. doi: 10.3390/ijms140917378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Falk K., Ernberg I., Sakthivel R., Davis J., Christensson B., Luka J. Expression of Epstein–Barr virus-encoded proteins and B-cell markers in fatal infectious mononucleosis. Int J Cancer. 1990;46:976–984. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910460605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tierney R.J., Steven N., Young L.S., Rickinson A.B. Epstein–Barr virus latency in blood mononuclear cells: analysis of viral gene transcription during primary infection and in the carrier state. J Virol. 1994;68:7374–7385. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7374-7385.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gordadze A.V., Poston D., Ling P.D. The EBNA2 polyproline region is dispensable for Epstein–Barr virus-mediated immortalization maintenance. J Virol. 2002;76:7349–7355. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.14.7349-7355.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gires O., Zimber-Strobl U., Gonnella R., Ueffing M., Marschall G., Zeidler R. Latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein–Barr virus mimics a constitutively active receptor molecule. EMBO J. 1997;16:6131–6140. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.20.6131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Farrell P.J. Signal transduction from the Epstein–Barr virus LMP-1 transforming protein. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:175–177. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zimber-Strobl U., Kempkes B., Marschall G., Zeidler R., Van Kooten C., Banchereau J. Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein (LMP1) is not sufficient to maintain proliferation of B cells but both it and activated CD40 can prolong their survival. EMBO J. 1996;15:7070–7078. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gregory C.D., Dive C., Henderson S., Smith C.A., Williams G.T., Gordon J. Activation of Epstein–Barr virus latent genes protects human B cells from death by apoptosis. Nature. 1991;349:612–614. doi: 10.1038/349612a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Henderson S., Rowe M., Gregory C., Croom-Carter D., Wang F., Longnecker R. Induction of bcl-2 expression by Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 protects infected B cells from programmed cell death. Cell. 1991;65:1107–1115. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90007-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Uchida J., Yasui T., Takaoka-Shichijo Y., Muraoka M., Kulwichit W., Raab-Traub N. Mimicry of CD40 signals by Epstein–Barr virus LMP1 in B lymphocyte responses. Science. 1999;286:300–303. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kang M.S., Kieff E. Epstein–Barr virus latent genes. Exp Mol Med. 2015;47:e131. doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ali A.S., Al-Shraim M., Al-Hakami A.M., Jones I.M. Epstein–Barr virus: clinical and epidemiological revisits and genetic basis of oncogenesis. Open Virol J. 2015;9:7–28. doi: 10.2174/1874357901509010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kikuchi K., Noguchi Y., de Rivera M.W., Hoshino M., Sakashita H., Yamada T. Detection of Epstein–Barr virus genome and latent infection gene expression in normal epithelia, epithelial dysplasia, and squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:3389–3404. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tsang N.M., Chang K.P., Lin S.Y., Hao S.P., Tseng C.K., Kuo T.T. Detection of Epstein–Barr virus-derived latent membrane protein-1 gene in various head and neck cancers: is it specific for nasopharyngeal carcinoma? Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1050–1054. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200306000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Iamaroon A., Khemaleelakul U., Pongsiriwet S., Pintong J. Co-expression of p53 and Ki67 and lack of EBV expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33:30–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2004.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cruz I., Van den Brule A.J., Steenbergen R.D., Snijders P.J., Meijer C.J., Walboomers J.M. Prevalence of Epstein–Barr virus in oral squamous cell carcinomas, premalignant lesions and normal mucosa—a study using the polymerase chain reaction. Oral Oncol. 1997;33:182–188. doi: 10.1016/s0964-1955(96)00054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Slot J., Saygun I., Sabeti M., Kubar A. Epstein–Barr virus in oral diseases. J Periodontal Res. 2006;41:235–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2006.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Iwakiri D. Epstein–Barr virus-encoded RNAs: key molecules in viral pathogenesis. Cancers. 2014;6:1615–1630. doi: 10.3390/cancers6031615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kulwichit W., Edwards R.H., Davenport E.M., Baskar J.F., Godfrey V., Raab-Traub N. Expression of the Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces B cell lymphoma in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11963–11968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Thornburg N.J., Kulwichit W., Edwards R.H., Shair K.H., Bendt K.M., Raab-Traub N. LMP1 signaling and activation of NF-kappaB in LMP1 transgenic mice. Oncogene. 2006;25:288–297. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dawson C.W., Rickinson A.B., Young L.S. Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein inhibits human epithelial cell differentiation. Nature. 1990;344:777–780. doi: 10.1038/344777a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yoshizaki T. Promotion of metastasis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein-1. Histol Histopathol. 2002;17:845–850. doi: 10.14670/HH-17.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kis A., Fehér E., Gál T., Tar I., Boda R., Tóth E.D. Epstein–Barr virus prevalence in oral squamous cell cancer and in potentially malignant oral disorders in an eastern Hungarian population. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;117:536–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cruz I., Van Den Brule A.J., Brink A.A., Snijiders P.J., Walboomers J.M., Van Der Waal I. No direct role for Epstein–Barr virus in oral carcinogenesis: a study at the DNA, RNA and protein levels. Int J Cancer. 2000;86:356–361. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000501)86:3<356::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lui V.W., Wong E.Y., Ho Y., Hong B., Wong S.C., Tao Q. STAT3 activation contributes directly to Epstein–Barr virus-mediated invasiveness of nasopharyngeal cancer cells in vitro. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1884–1893. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Liu Y.P., Tan Y.N., Wang Z.L., Zeng L., Lu Z.X., Li L.L. Phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of STAT3 regulated by the Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Mol Med. 2008;21:153–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fang W., Zhang J., Hong S., Zhan J., Chen N., Qin T. EBV-driven LMP1 and IFN-γ up-regulate PD-L1 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: implications for oncotargeted therapy. Oncotarget. 2014;5:12189–12202. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chen H., Hutt-Fletcher L., Cao L., Hayward S.D. A positive autoregulatory loop of LMP1 expression and STAT activation in epithelial cells latently infected with Epstein–Barr virus. J Virol. 2003;77:4139–4148. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.7.4139-4148.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dojcinov S.D., Venkataraman G., Raffeld M., Pittaluga S., Jaffe E.S. EBV positive mucocutaneous ulcer—a study of 26 cases associated with various sources of immunosuppression. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(March (3)):405–417. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181cf8622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kikuchi K., Ishige T., Ide F., Ito Y., Saito I., Hoshino M. Overexpression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase in MTX- and age-related Epstein–Barr virus-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders of the head and neck. J Oncol. 2015;2015:605750. doi: 10.1155/2015/605750. Epub 2015 Mar 5. PubMed PMID: 25834572; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4365324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jaffe E.S., Harris N.L., Swerdlow S.J. Immunodeficiency-associated lymphoproliferative disorder. In: Swerdlow S.J., Campo E., Harris N.L., Jaffe E.S., Pileri S.A., Stein H., Thiele J., Vardiman J.W., editors. World Health Organization classification of tumors of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. IARC; Lyon: 2008. pp. 335–351. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Oyama T., Ichimura K., Suzuki R., Suzumiya J., Ohshima K., Yatabe Y. Senile EBV+ B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a clinicopathological study of 22 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:16–26. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tishler M., Caspi D., Yaron M. Long-term experience with low dose methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 1993;13:103–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00290296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Salloum E., Cooper D.L., Howe G., Lacy J., Tallini G., Crouch J. Spontaneous regression of lymphoproliferative disorders in patients treated with methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis and other rheumatic diseases. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1943–1949. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.6.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Menke D.M., Griesser H., Moder K.G., Tefferi A., Luthra H.S., Cohen M.D. Lymphomas in patients with connective tissue disease. Comparison of p53 protein expression and latent EBV infection in patients immunosuppressed and not immunosuppressed with methotrexate. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:212–218. doi: 10.1309/VF28-E64G-1DND-LF94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Oyama T., Ichimura K., Suzuki R., Suzumiya J., Ohshima K., Yatabe Y. Senile EBV+ B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a clinicopathologic study of 22 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:16–26. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Borisch B., Raphael M., Swerdlow S.H., Jaffe E.S. Immunodeficiency associated lymphoproliferative disorders. In: Harris N.L., Stein H., Vardiman J.W., Jaffe E.S., editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. IARC Press; Lyon: 2001. pp. 255–271. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Oyama T., Yamamoto K., Asano N., Oshiro A., Suzuki R., Kagami Y. Age-related EBV-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders constitute a distinct clinicopathologic group: a study of 96 patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5124–5132. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nakamura S., Jaffe E.S., Swerdlow S.H. EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly. In: Swerdlow S.J., Campo E., Harris N.L., Jaff E.S., Pileri S.A., Stein H., Thiele J., Vardiman J.W., editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. IARC Press; Lyon: 2008. pp. 243–244. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kanegane H., Wakiguchi H., Kanegane C., Kurashige T., Tosato G. Viral interleukin-10 in chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:254–257. doi: 10.1086/517260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kojima M., Kashimura M., Itoh H., Noro A., Akikusa B., Iijima M. Epstein–Barr virus-related reactive lymphoproliferative disorders in middle-age or elderly patients presenting with atypical features. A clinicopathological study of six cases. Pathol Res Pract. 2007;203:587–591. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kutok J.L., Wang F. Spectrum of Epstein–Barr virus-associated diseases. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:375–404. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Murray P.G., Young L.S., Rowe M., Crocker J. Immunohistochemical demonstration of the Epstein–Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein in paraffin sections of Hodgkin’s disease. J Pathol. 1992;166:1–5. doi: 10.1002/path.1711660102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Peng M., Lundgren E. Transient expression of the Epstein–Barr virus LMP1 gene in human primary B cells induces cellular activation and DNA synthesis. Oncogene. 1992;7(September):1775–1782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Huen D.S., Henderson S.A., Croom-Carter D., Rowe M. The Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 (LMP1) mediates activation of NF-kappa B and cell surface phenotype via two effector regions in its carboxy-terminal cytoplasmic domain. Oncogene. 1995;10:549–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cahir McFarland E.D., Izumi K.M., Mosialos G. Epstein–Barr virus transformation: involvement of latent membrane protein 1-mediated activation of NF-kappaB. Oncogene. 1999;18:6959–6964. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Baumforth K.R., Young L.S., Flavell K.J., Constandinou C., Murray P.G. The Epstein–Barr virus and its association with human cancers. Mol Pathol. 1999;52:307–322. doi: 10.1136/mp.52.6.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kim J.H., Kim W.S., Kang J.H., Lim H.Y., Ko Y.H., Park C. Egr-1, a new downstream molecule of Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein 1. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:623–628. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kim J.H., Kim W.S., Park C. SNARK, a novel downstream molecule of EBV latent membrane protein 1, is associated with resistance to cancer cell death. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:1392–1398. doi: 10.1080/10428190802087454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.He B., Raab-Traub N., Casali P., Cerutti A. EBV-encoded latent membrane protein 1 cooperates with BAFF/BLyS and APRIL to induce T cell-independent Ig heavy chain class switching. J Immunol. 2003;171:5215–5224. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Epeldegui M., Hung Y.P., McQuay A., Ambinder R.F., Martínez-Maza O. Infection of human B cells with Epstein–Barr virus results in the expression of somatic hypermutation-inducing molecules and in the accrual of oncogene mutations. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:934–942. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Komeno Y., Kitaura J., Watanabe-Okochi N., Kato N., Oki T., Nakahara F. AID-induced T-lymphoma or B-leukemia/lymphoma in a mouse BMT model. Leukemia. 2010;24:1018–1024. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Muramatsu M., Sankaranand V.S., Anant S., Sugai M., Kinoshita K., Davidson N.O. Specific expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a novel member of the RNA-editing deaminase family in germinal center B cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18470–18476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Revy P., Muto T., Levy Y., Geissmann F., Plebani A., Sanal O. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) deficiency causes the autosomal recessive form of the Hyper-IgM syndrome (HIGM2) Cell. 2000;102:565–575. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Muramatsu M., Kinoshita K., Fagarasan S., Yamada S., Shinkai Y., Honjo T. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000;102:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.de Yébenes V.G., Ramiro A.R. Activation-induced deaminase: light and dark sides. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:432–439. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Longerich S., Basu U., Alt F., Storb U. AID in somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Delker R.K., Fugmann S.D., Papavasiliou F.N. A coming-of-age story: activation-induced cytidine deaminase turns 10. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1147–1153. doi: 10.1038/ni.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Kuraoka M., McWilliams L., Kelsoe G. AID expression during B-cell development: searching for answers. Immunol Res. 2011;49:3–13. doi: 10.1007/s12026-010-8185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Park S.R. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase in B cell immunity and cancers. Immune Netw. 2012;12:230–239. doi: 10.4110/in.2012.12.6.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Robbiani D.F., Nussenzweig M.C. Chromosome translocation, B cell lymphoma, and activation-induced cytidine deaminase. Annu Rev Pathol. 2013;8:79–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-164004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Pasqualucci L., Guglielmino R., Houldsworth J., Mohr J., Aoufouchi S., Polakiewicz R. Expression of the AID protein in normal and neoplastic B cells. Blood. 2004;104:3318–3325. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Cattoretti G., Büttner M., Shaknovich R., Kremmer E., Alobeid B., Niedobitek G. Nuclear and cytoplasmic AID in extrafollicular and germinal center B cells. Blood. 2006;107:3967–3975. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kim J.H., Kim W.S., Park C. Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 increases genomic instability through Egr-1-mediated up-regulation of activation-induced cytidine deaminase in B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:2035–2040. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.769218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Milbrandt J. A nerve growth factor-induced gene encodes a possible transcriptional regulatory factor. Science. 1987;238:797–799. doi: 10.1126/science.3672127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Bhattacharyya S., Fang F., Tourtellotte W., Varga J. Egr-1: new conductor for the tissue repair orchestra directs harmony (regeneration) or cacophony (fibrosis) J Pathol. 2013;229:286–297. doi: 10.1002/path.4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Rickinson A.B., Kieff E. Epstein–Barr virus. In: Knipe D.M., Howley P.M., editors. Fields virology. 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2001. pp. 2575–2627. [Google Scholar]

- 148.Calogero A., Cuomo L., D’Onofrio M., de Grazia U., Spinsanti P., Mercola D. Expression of Egr-1 correlates with the transformed phenotype and the type of viral latency in EBV genome positive lymphoid cell lines. Oncogene. 1996;13:2105–2112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Chang Y., Lee H.H., Chen Y.T., Lu J., Wu S.Y., Chen C.W. Induction of the early growth response 1 gene by Epstein–Barr virus lytic transactivator Zta. J Virol. 2006;80:7748–7755. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02608-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]