Abstract

Study design

Prospective

Objectives

To test whether provocative stimulation of the testes identifies men with chronic spinal cord injury (SCI), a population in which serum testosterone concentrations are often depressed, possibility due to gonadal dysfunction. To accomplish this objective, conventional and lower than the conventional doses of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) were administered.

Methods

Thirty men with chronic SCI [duration of injury >1 year; 18 and 65 years old; 16 eugonadal (>12.1 nmol/l) and 14 hypogonadal (≤12.1 nmol/l)] or able-bodied (AB) men [11 eugonadal and 27 hypogonadal] were recruited for the study. Stimulation tests were performed to quantify testicular responses to the intramuscular administration of hCG at three dose concentrations (i.e., 400 IU, 2000 IU, and 4000 IU). The hCG was administered on two consecutive days and blood was collected for serum testosterone in the early morning prior to each of two injections; subjects returned on day 3 for a final blood sample collection.

Results

The average gonadal response in the SCI and AB groups to each dose of hCG was not significantly different in the hypogonadal or eugonadal subjects, with the mean serum testosterone concentrations in all groups demonstrating an adequate response.

Conclusions

This work confirmed the absence of primary testicular dysfunction without additional benefit demonstrated of provocative stimulation of the testes with lower than conventional doses of hCG. Our findings support prior work that suggested a secondary testicular dysfunction occurs in a majority of those with SCI and depressed serum testosterone concentrations.

Keywords: testosterone, human chorionic gonadotropin, hypogonadism, tetraplegia, paraplegia

INTRODUCTION

Serum testosterone concentrations have been reported to be depressed in men with chronic spinal cord injury (SCI) (1–4). Depressed levels of testosterone may be associated with infertility but also have a profound effect on body composition, musculoskeletal function, and mood (5–8). The potential reasons for low levels of testosterone in the SCI population may include chronic illness, stress, nutritional factors, and use of centrally-acting medications (9–12). Primary testicular failure, regardless of the etiology, may be responsible for low levels of circulating testosterone. Determination of whether an appropriate response to gonadal stimulation occurs will provide an answer as to whether the hypogonadism, frequently observed in men with SCI, is primary in origin, or a secondary to pituitary-hypothalamic dysfunction.

In men with SCI, gonadal stimulation to a conventional dose of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG 4000 IU) has recently been reported to be associated with a normal gonadal response—that is, an appropriate rise in serum testosterone concentration to provocative stimulation, regardless of whether a subject was classified as being hypogonadal or eugonadal (13). Patron et al. reported that the magnitude of the testosterone response varies directly with the dose of hCG administered; circulating testosterone levels rise with a hCG dose of 375 IU and were maximally stimulated with a dose of 6,000 IU, the highest dose administered in this report (14). It is generally accepted that the dose of hCG to produce maximum testicular stimulation is between 6,000 and 10,000 IU (14–16). Of note, doses of hCG above approximately 2,000 IU are associated with pharmacological levels of plasma hCG and result in the Leydig cell being refractory to additional doses of hCG (14, 17). It may be speculated that the routine clinical test of Leydig cell function that serves to maximally stimulate the testes may not be sufficiently sensitive to identify more subtle forms of testicular dysfunction. In our previous report (13), the possibility was hypothesized that a lower dose of hCG would be able to differentiate between those who had lesser degrees of gonadal dysfunction from those who had responded adequately to a conventional dose of hCG. To address this possibility, stimulation of the testes was performed in a conventional manner, as well as with lower doses of hCG, in a cohort of men with chronic SCI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study cohort

Subjects were recruited from the James J. Peters VA Medical Center (JJP VAMC), Bronx, NY, and the Kessler Institute of Rehabilitation (KIR), West Orange, NJ. Otherwise healthy men, between the ages of 18 and 65 with chronic SCI (duration of injury >1 year) or healthy men who were neurologically intact [able-bodied (AB)] were considered for screening for study eligibility. Because the group with SCI was recruited from a convenience sample, and approximately half of the SCI participants were found to have serum testosterone concentrations below the normal range without an apparent etiology for this condition, an effort was made to recruit a similar distribution in the AB group by randomly screening a convenience sample of individuals for serum testosterone concentration to permit identification of a sufficient number of subjects with low values for enrollment. Exclusion criteria consisted of the following conditions: acute illness; active thyroid disease; medications for depression, mood changes or any nervous system condition; centrally acting high blood pressure medications (i.e., guanethidine, reserpine, methyldopa, β-adrenergic blockers, clonidine, etc.); medications for gastrointestinal disorders; medication for heart disease; medications for seizures (i.e., dilantin or barbiturates); epilepsy; congestive heart failure; anti-cancer medications; antibiotics; pain medications; hormones (other than replacement doses); history of pituitary or testicular surgery; and/or less than 18 or older than 65 years of age. Abstinence from alcohol containing beverages was required for 48 hours prior to study procedures. The research study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the JJP VAMC and the KIR. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject prior to study participation.

Procedures

This was a prospective, open-label, parallel group investigation to differentiate between normal and abnormal testicular function in men with SCI. Baseline screening blood samples were taken from eligible participants to assist in differentiating and grouping those with normal serum testosterone concentrations (eugonadal: >12.1 nmol/l) from those with low serum testosterone concentrations (hypogonadal: ≤12.1 nmol/l). To determine the differential secretion of testosterone to provocative stimulation, intramuscular hCG was administered at three dose concentrations (i.e., 400 IU, 2000 IU, and 4000 IU; Novarel, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Parsippany, NJ, USA). Serial blood draws permitted a dose response curve to be obtained for each of the three stimulation tests. One of the three dose concentrations was administered each week, with each subject completing 3 consecutive days of testing for each of the hCG doses; hCG was administered intramuscularly on two consecutive days with blood collected for serum testosterone between 8 and 9 am prior to each of two injections, with subjects returning on day 3 for a final blood sample collection. The visits between the respective dose administrations were separated by a minimum of one week. On average, the participants completed the three-dose visits within 3-month period. A randomized order was used to administer the dose concentrations. Blood samples from the study visits were centrifuged and the serum was separated for the determination of testosterone using a commercial kit assay (ICN Biomedicals, Inc., Costa Mesa, CA). Serum samples were frozen at −70°C until batch processing at the completion of all testing. The serum testosterone concentration was determined in duplicate by radioimmunoassay, in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. The sensitivity for the testosterone assay was 3 nmol/l; the intra-assay CV were 9.6, 8.1, and 7.8% for testosterone concentrations of 3, 24, and 69 nmol/l, respectively; the inter-assay CV were 8.6, 9.1, and 8.4% for testosterone concentrations of 2, 21, and 56 nmol/l, respectively; the 2 standard deviation normal range for adult males is 9.7–30.5 nmol/l.

Statistical Analyses

Values are expressed as group mean ± SD. Chi-square tests were performed to determine group differences for categorical variables. AB and SCI participants were designated as being Eugonadal or Hypogonadal from the baseline serum testosterone concentration. To aid in statistical comparisons, the primary (AB or SCI) and gonadal status (Eugonadal or Hypogonadal) group designations were combined to produce a concatenated variable to form four groups: AB-Eugonadal, AB-Hypogonadal, SCI-Eugonadal, and SCI-Hypogonadal. Factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to identify group differences for demographic [age, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), duration of injury] and baseline testosterone concentrations. To determine if group differences were present in the stimulated testosterone responses within (Day 1, 2 or 3) or between doses (hCG: 400 IU, 2000 IU and 4000 IU), a one-factor three level (dose) ANOVA with repeated measures on time (Day 1, 2 or 3) was performed. A separate repeated measures ANOVA was performed to determine if the serum testosterone concentrations were different at the respective Day 1 visits for each dose concentration. To further identify and describe significant main effects in the stimulated dose responses, Bonferoni post-hoc tests were applied to the respective time points and group comparisons. An a priori level of significance was set at p≤0.05. Statistical analyses were completed using IBM SPSS Statistics 21 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Demographic data for subjects in the AB-Eugonadal, AB-Hypogonadal, SCI-Eugonadal, and SCI-Hypogonadal groups are provided (Table 1). The groups were matched for demographic characteristics, but, by study design, differed for serum testosterone concentration with the SCI-Hypogonadal and AB-Hypogonadal groups having significantly reduced concentrations compared to their respective Eugonadal group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Groups

| Spinal Cord Injury | Able-Bodied | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eugonadal | Hypogonadal | Eugonadal | Hypogonadal | ||

|

| |||||

| n | 16 | 14 | 11 | 27 | - |

| Age (years) | 33 ± 7 | 41 ± 10 | 36 ± 7 | 36 ± 9 | 0.06 |

| Height (m) | 1.79 ± 0.08 | 1.78 ± 0.07 | 1.82 ± 0.10 | 1.76 ± 0.08 | NS |

| Weight (kg) | 88.1 ± 20.1 | 81.7 ± 15.2 | 87.6 ± 11.3 | 83.6 ± 14.0 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.3 ± 4.5 | 25.4 ± 4.0 | 26.4 ± 3.3 | 26.8 ± 3.8 | NS |

| DOI (years) | 11 ± 7 | 12 ± 10 | - | - | NS |

| Paraplegia/Tetraplegia (n) | 11/5 | 10/4 | - | - | NS |

| Total Testosterone (nmol/l) | 17.4 ± 4.4 | 7.4 ± 3.8 *,† | 16.7 ± 4.3 | 7.7 ± 2.3 ‡,¶ | <0.0001 |

Data are presented as group mean ± SD.

Abbreviations: BMI=body mass index; DOI= duration of injury; NS= not significant; SCI- spinal cord injury; AB= able-bodied.

p<0.0001: SCI-Eugonadal vs. SCI-Hypogonadal;

p<0.0001: AB-Eugonadal vs. SCI-Hypogonadal;

p<0.0001: AB-Eugonadal vs. SCI-Hypogonadal;

p<0.0001: AB-Eugonadal vs AB-Hypogonadal.

hCG Provocative Stimulation

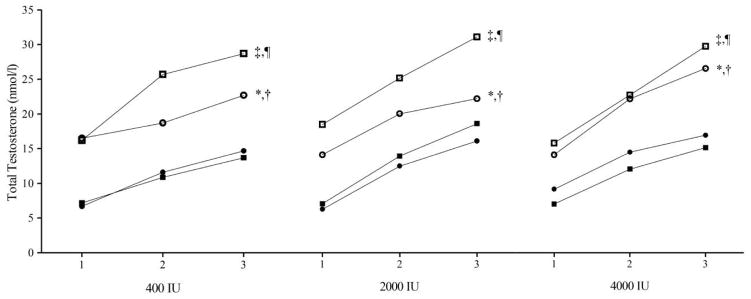

Provocative stimulation with hCG was performed at 3 doses; each dose of hCG was administered twice with blood collection over 3 consecutive days (Figure 1). Day 1 serum testosterone concentrations—that is, prior to each of the three hCG doses— were not significantly different within the eugonadal and hypogonadal groups. The serum testosterone concentration increased significantly for each group regardless of the dose of hCG (i.e., 400 IU, 2000 IU and 4000 IU). Within each group, the magnitude of the response of the serum testosterone concentration across the doses of hCG was similar. In all groups, the highest serum testosterone concentrations were observed by Day 3 of each hCG dose. Whereas the AB-Eugonadal and SCI-Eugonadal groups had statistically greater absolute serum testosterone responses than each of the Hypogonadal groups (Figure 1), the average serum testosterone response above baseline for each of the three doses of hCG within and between the Eugonadal groups and the Hypogonadal groups was not significantly different. The mean serum testosterone concentration post-stimulation in both hypogonadal groups exceeded the lower limit of normal (e.g., >12.1 nmol/l). Of note, not all subjects in the hypogonadal groups exceeded the lower limit of normal for the response of serum testosterone concentration at each one of the three doses of hCG: at the 400 IU dose, 3 of 14 SCI-Hypogonadal subjects had values less than the lower limit of normal for testosterone, as did 11 of 27 AB-Hypogonadal subjects; at the 2000 IU dose, 5 of 27 SCI-Hypogonadal subjects had values less than the lower limit of normal for testosterone, as did 5 of 27 AB-Hypogonadal subjects; at the 4000 IU dose, 3 of 14 SCI-Hypogonadal subjects had values less than the lower limit of normal for testosterone, as did 7 of 27 AB-Hypogonadal subjects. All subjects, in all groups responded with an adequate rise in serum testosterone concentration to one or more of the three doses of hCG. An exploratory post-hoc analysis failed to identify a demographic characteristic (i.e., age, weight, BMI, or in SCI, duration of injury) associated with subjects who failed to raise serum testosterone levels into the normal range after provocative stimulation.

Figure 1. Serum Testosterone Responses to Stimulation by hCG at 400 IU, 2000 IU and 4000 IU.

Data are presented as group mean with standard deviation bars redacted for enhanced visualization of group serum testosterone responses. Standard deviation is provided by dose (i.e., 400 IU, 2000 IU and 4000 IU) and Day (i.e., 1, 2, and 3) in each group for serum testosterone concentrations (400 IU- AB-Eugonadal: 9.0, 8.6, 6.7 nmol/l; AB- Hypogonadal: 3.3, 4.5, 6.5 nmol/l; SCI-Eugonadal: 6.2, 8.6, 9.5 nmol/l; SCI-Hypogonadal: 3.8, 6.8, 6.1 nmol/l); (2000 IU- AB-Eugonadal: 4.5, 5.2, 7.5 nmol/l; AB- Hypogonadal: 3.0, 4.5, 6.6 nmol/l; SCI-Eugonadal: 7.7, 8.2, 12.4 nmol/l; SCI-Hypogonadal: 5.2, 6.2, 10.4 nmol/l); and (4000 IU- AB-Eugonadal: 6.8, 8.6, 10.5 nmol/l; AB- Hypogonadal: 5.1, 8.6, 8.6 nmol/l; SCI-Eugonadal: 8.7, 7.2, 8.3 nmol/l; SCI-Hypogonadal: 5.2, 5.7, 7.7 nmol/l). The omnibus statistical models at each dose were statistically significant for group and time main effects, but no group by time interaction was observed. *p<0.01: SCI-Eugonadal vs. SCI-Hypogonadal; †p<0.01: SCI-Eugonadal vs. AB-Hypogonadal; ‡p<0.01: AB-Eugonadal vs. SCI-Hypogonadal; p<0.01: AB-Eugonadal vs AB-Hypogonadal.

DISCUSSION

Circulating testosterone concentrations have long been of interest to physicians caring for men with SCI because of well appreciated problems with fertility and impotence (5, 18–25), as well as the global effects on function and quality of life. Primary testicular and/or central dysfunction may lead to impaired spermatogenesis and infertility (26–30). In the general population, primary testicular failure is responsible for the majority of patients with male infertility; about half of these cases have no apparent etiology (30). Testosterone is also the major anabolic hormone in adult men. A deficiency of testosterone may be expected to have adverse effects on bone, soft tissue body composition, exercise tolerance, and psychological well-being (6–8, 31).

Serum testosterone concentrations have been reported to be depressed in persons with chronic SCI (1–4). Testicular failure of primary or secondary origin may be due to one or more etiologies (e.g., chronic illness, emotional stress, nutritional factors, medications, and local thermal gonadal conditions) (9–11, 32–38). In this study we hypothesized that by performing graded stimulation of the testes, a more subtle dysfunction of the Leydig cell, if present, may be revealed. Of note, the average response of SCI and AB participants, regardless of group affiliation by baseline testicular function (e.g., eugonadal or hypogonadal), was not significantly different. This finding supports and extends an earlier finding by our group that the testicular response to stimulation with a standard dose of hCG was generally appropriate. It should be mentioned that a minority of participants in each of the hypogonadal and eugonadal groups, regardless of whether SCI or AB, failed to raise serum testosterone concentrations into the normal range after administration of each of the three doses of hCG. As such, not all subjects with SCI can unequivocally be stated to have an absence of end organ dysfunction. The finding that hCG did not stimulate the testes to release testosterone into the normal range after each dose of hCG in those with SCI may merely represent chronic hypo-stimulation of the end organ by gonadotropins with the testes lacking the ability to respond adequately to a relatively short course of provocative stimulation. However, a mild primary end organ disorder may also be considered.

Gonadal release of testosterone by Leydig cells is under the regulation of the pituitary gland, and, more specifically, the episodic, pulsatile release of luteinizing hormone. In the classic feedback loop, if an individual has primary testicular failure, serum testosterone levels are depressed and plasma luteinizing hormone levels are elevated. Indeed, some investigators have reported elevated basal or stimulated levels of plasma luteinizing hormone when serum testosterone levels are low in cohorts of subjects with SCI (39–41). However, as in our report herein, other investigators have reported in persons with SCI that the basal levels of plasma luteinizing hormone were not elevated despite the presence of depressed serum testosterone concentrations (12, 42, 43). As previously discussed, a subset of our hypogonadal subjects with SCI did not have adequate responses to one or more doses of hCG. Indeed, individuals with such a hormonal picture (e.g., hypogonadal with normal basal plasma luteinizing hormone levels) may represent a heterogeneous group of individuals with a mixture of central and/or peripheral dysfunction, as determined by a variety of pituitary and gonadal stimulation tests in an AB population (44).

It is intriguing to consider the possibility that feedback from the testes could influence central gonadotropin function, and hence testicular function. Inhibin is a gonadal peptide that suppresses follicular stimulating hormone release and acts to regulate the function of the pituitary-gonadal axis (45, 46). Inhibin B is the predominant circulating and centrally active form that is also accepted as a marker of Sertoli cell function (47), and levels of inhibin have a diurnal variation in normal men, with a reduction of levels reported with advancing age (48, 49). With interruption of nervous innervation to the testes, it is likely that the normal diurnal patterns for both testosterone and inhibin are absent, with possible adverse central consequences on gonadotropin regulation. The hypothesized central dysregulation may result by interfering with the normal stimulatory effect of activins both on follicular stimulating hormone release, thus possibly decreasing hormone levels, and on gonadotropin releasing hormone receptor concentration in the basal and stimulated states (50, 51), decreasing receptor availability, and by doing so, modulating gonadotrope sensitivity to gonadotropin releasing hormone.

In an earlier article by our group, the pituitary-testicular axis was evaluated by the administration of conventional gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulation test of the pituitary and hCG stimulation test of the gonads (13). An exaggerated gonadotropin response of the pituitary gland to provocative stimulation may suggest end organ dysfunction, however in the majority of subjects, the testes responded normally to stimulation, regardless of whether the participants were eugonadal or hypogonadal; as such, the possibility of diminished hypothalamic drive to the pituitary was raised as the most likely alternative explanation (13). The authors concluded that a disorder of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis was indeed present, but it was suggested that a graded provocative stimulation of the testes may be worthwhile to perform in an effort to unmask a more subtle deficit in end organ function. The work presented herein suggests that, even after provocative testing at two lower doses of hCG, testicular function was generally normal in a cohort of men with SCI, regardless of baseline gonadal status.

CONCLUSION

Stimulation of the testes with hCG in an incremental fashion in men with SCI demonstrated a normal response of testosterone, regardless of baseline gonadal status. This finding adds support to the prior work that suggested a secondary testicular failure, likely hypothalamic in origin, is present in a majority of those with depressed serum testosterone concentrations. However, because not all subjects responded appropriately to gonadal stimulation at each dose of hCG administered, the SCI population may also have a minority of individuals with impaired testicular function that may be partially responsible for depressed levels of serum testosterone.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the James J. Peters VA Medical Center, Bronx, NY, the Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research & Development Service, and the Kessler Institute for Rehabilitation, West Orange, NJ for their support. This work was funded by the Veteran Affairs Rehabilitation Research & Development National Center for the Medical Consequences of Spinal Cord Injury (B2648-C, B4162-C & B9212-C).

Grant Sources: Veteran Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service (#B2468-C, #B4162-C, and #B9212-C) and the James J. Peters VA Medical Center.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None to declare

Clinical Trial Registration Number: NCT00223860

References

- 1.Bauman WA, La Fountaine MF, Spungen AM. Age-related prevalence of low testosterone in men with spinal cord injury. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 2014;37(1):32–9. doi: 10.1179/2045772313Y.0000000122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark MJ, Schopp LH, Mazurek MO, Zaniletti I, Lammy AB, Martin TA, et al. Testosterone levels among men with spinal cord injury: relationship between time since injury and laboratory values. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87(9):758–67. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181837f4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durga A, Sepahpanah F, Regozzi M, Hastings J, Crane DA. Prevalence of testosterone deficiency after spinal cord injury. PM R. 2011;3(10):929–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schopp LH, Clark M, Mazurek MO, Hagglund KJ, Acuff ME, Sherman AK, et al. Testosterone levels among men with spinal cord injury admitted to inpatient rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(8):678–84. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000228617.94079.4a. quiz 85–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naderi AR, Safarinejad MR. Endocrine profiles and semen quality in spinal cord injured men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2003;58(2):177–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tenover JL. Therapeutic perspective: Issues in testosterone replacement in older men. Can replacement doses of testosterone produce clinically meaningful changes in body composition in older men? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(10):3439–40. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.10.5060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auyeung TW, Lee JS, Kwok T, Leung J, Ohlsson C, Vandenput L, et al. Testosterone but not estradiol level is positively related to muscle strength and physical performance independent of muscle mass: a cross-sectional study in 1489 older men. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164(5):811–7. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hintikka J, Niskanen L, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Tolmunen T, Honkalampi K, Lehto SM, et al. Hypogonadism, decreased sexual desire, and long-term depression in middle-aged men. J Sex Med. 2009;6(7):2049–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray A, Feldman HA, McKinlay JB, Longcope C. Age, disease, and changing sex hormone levels in middle-aged men: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;73(5):1016–25. doi: 10.1210/jcem-73-5-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedl KE, Moore RJ, Hoyt RW, Marchitelli LJ, Martinez-Lopez LE, Askew EW. Endocrine markers of semistarvation in healthy lean men in a multistressor environment. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2000;88(5):1820–30. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.5.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isidori AM, Lenzi A. Risk factors for androgen decline in older males: lifestyle, chronic diseases and drugs. J Endocrinol Invest. 2005;28(3 Suppl):14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daniell HW. Hypogonadism in men consuming sustained-action oral opioids. J Pain. 2002;3(5):377–84. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2002.126790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bauman WA, La Fountaine MF, Cirnigliaro CM, Kirshblum SC, Spungen AM. Provocative stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis in men with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2016 doi: 10.1038/sc.2016.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padron RS, Wischusen J, Hudson B, Burger HG, de Kretser DM. Prolonged biphasic response of plasma testosterone to single intramuscular injections of human chorionic gonadotropin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1980;50(6):1100–4. doi: 10.1210/jcem-50-6-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smals AG, Pieters GF, Drayer JI, Benraad TJ, Kloppenborg PW. Leydig cell responsiveness to single and repeated human chorionic gonadotropin administration. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1979;49(1):12–4. doi: 10.1210/jcem-49-1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okuyama A, Namiki M, Koide T, Itatani H, Mizutani S, Sonoda T, et al. A simple hCG stimulation test for normal and hypogonadal males. Arch Androl. 1981;6(1):75–81. doi: 10.3109/01485018108987349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forest MG, Lecoq A, Saez JM. Kinetics of human chorionic gonadotropin-induced steroidogenic response of the human testis. II. Plasma 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone, delta4-androstenedione, estrone, and 17 beta-estradiol: evidence for the action of human chorionic gonadotropin on intermediate enzymes implicated in steroid biosynthesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1979;49(2):284–91. doi: 10.1210/jcem-49-2-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brackett NL, Lynne CM, Weizman MS, Bloch WE, Abae M. Endocrine profiles and semen quality of spinal cord injured men. J Urol. 1994;151(1):114–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34885-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munro D, Horne HW, Jr, Paull DP. The effect of injury to the spinal cord and cauda equina on the sexual potency of men. N Engl J Med. 1948;239(24):903–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM194812092392401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horne HW, Paull DP, Munro D. Fertility studies in the human male with traumatic injuries of the spinal cord and cauda equina. N Engl J Med. 1948;239(25):959–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM194812162392504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bors E, Engle ET, Rosenquist RC, Holliger VH. Fertility in paraplegic males; a preliminary report of endocrine studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1950;10(4):381–98. doi: 10.1210/jcem-10-4-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ver Voort SM. Infertility in spinal-cord injured male. Urology. 1987;29(2):157–65. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(87)90145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beretta G, Chelo E, Zanollo A. Reproductive aspects in spinal cord injured males. Paraplegia. 1989;27(2):113–8. doi: 10.1038/sc.1989.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linsenmeyer TA. Male infertility following spinal cord injury. J Am Paraplegia Soc. 1991;14(3):116–21. doi: 10.1080/01952307.1991.11735840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang HF, Li MT, Giglio W, Anesetti R, Ottenweller JE, Pogach LM. The detrimental effects of spinal cord injury on spermatogenesis in the rat is partially reversed by testosterone, but enhanced by follicle-stimulating hormone. Endocrinology. 1999;140(3):1349–55. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.3.6583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meeker JD, Godfrey-Bailey L, Hauser R. Relationships between serum hormone levels and semen quality among men from an infertility clinic. J Androl. 2007;28(3):397–406. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.106.001545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sina D, Schuhmann R, Abraham R, Taubert HD, Dericks-Tan JS. Increased serum FSH levels correlated with low and high sperm counts in male infertile patients. Andrologia. 1975;7(1):31–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1975.tb01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Subhan F, Tahir F, Ahmad R, Khan ZD. Oligospermia and its relation with hormonal profile. JPMA The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 1995;45(9):246–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen TK, Andersson AM, Jorgensen N, Andersen AG, Carlsen E, Petersen JH, et al. Body mass index in relation to semen quality and reproductive hormones among 1,558 Danish men. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(4):863–70. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krausz C. Male infertility: pathogenesis and clinical diagnosis. Best practice & research Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 2011;25(2):271–85. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Storer TW, Woodhouse L, Magliano L, Singh AB, Dzekov C, Dzekov J, et al. Changes in muscle mass, muscle strength, and power but not physical function are related to testosterone dose in healthy older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(11):1991–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01927.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tuck SP, Francis RM. Testosterone, bone and osteoporosis. Front Horm Res. 2009;37:123–32. doi: 10.1159/000176049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finkelstein JS, Yu EW, Burnett-Bowie SA. Gonadal steroids and body composition, strength, and sexual function in men. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(25):2457. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1313169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhasin S, Storer TW, Berman N, Callegari C, Clevenger B, Phillips J, et al. The effects of supraphysiologic doses of testosterone on muscle size and strength in normal men. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(1):1–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607043350101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snyder PJ, Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Matsumoto AM, Stephens-Shields AJ, Cauley JA, et al. Effects of Testosterone Treatment in Older Men. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):611–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cherrier MM, Anderson K, Shofer J, Millard S, Matsumoto AM. Testosterone treatment of men with mild cognitive impairment and low testosterone levels. American journal of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. 2015;30(4):421–30. doi: 10.1177/1533317514556874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith HS, Elliott JA. Opioid-induced androgen deficiency (OPIAD) Pain physician. 2012;15(3 Suppl):ES145–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubinstein A, Carpenter DM. Elucidating risk factors for androgen deficiency associated with daily opioid use. Am J Med. 2014;127(12):1195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perkash I, Martin DE, Warner H, Blank MS, Collins DC. Reproductive biology of paraplegics: results of semen collection, testicular biopsy and serum hormone evaluation. J Urol. 1985;134(2):284–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)47126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayes PJ, Krishnan KR, Diver MJ, Hipkin LJ, Davis JC. Testicular endocrine function in paraplegic men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1979;11(5):549–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1979.tb03107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang TS, Wang YH, Chiang HS, Lien YN. Pituitary-testicular and pituitary-thyroid axes in spinal cord-injured males. Metabolism. 1993;42(4):516–21. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(93)90112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kikuchi TA, Skowsky WR, El-Toraei I, Swerdloff R. The pituitary-gonadal axis in spinal cord injury. Fertil Steril. 1976;27(10):1142–5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)42130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morley JE, Distiller LA, Lissoos I, Lipschitz R, Kay G, Searle DL, et al. Testicular function in patients with spinal cord damage. Horm Metab Res. 1979;11(12):679–82. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1092799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glass AR. Pituitary-testicular reserve in men with low serum testosterone and normal serum luteinizing hormone. J Androl. 1988;9(3):224–30. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.1988.tb01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gregory SJ, Kaiser UB. Regulation of gonadotropins by inhibin and activin. Seminars in reproductive medicine. 2004;22(3):253–67. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-831901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bilezikjian LM, Blount AL, Donaldson CJ, Vale WW. Pituitary actions of ligands of the TGF-beta family: activins and inhibins. Reproduction. 2006;132(2):207–15. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.01073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iliadou PK, Tsametis C, Kaprara A, Papadimas I, Goulis DG. The Sertoli cell: Novel clinical potentiality. Hormones. 2015;14(4):504–14. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tenover JS, Bremner WJ. Circadian rhythm of serum immunoreactive inhibin in young and elderly men. J Gerontol. 1991;46(5):M181–4. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.5.m181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chong YH, Pankhurst MW, McLennan IS. The Daily Profiles of Circulating AMH and INSL3 in Men are Distinct from the Other Testicular Hormones, Inhibin B and Testosterone. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang QF, Farnworth PG, Findlay JK, Burger HG. Inhibitory effect of pure 31-kilodalton bovine inhibin on gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-induced up-regulation of GnRH binding sites in cultured rat anterior pituitary cells. Endocrinology. 1989;124(1):363–8. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-1-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Winters SJ, Pohl CR, Adedoyin A, Marshall GR. Effects of continuous inhibin administration on gonadotropin secretion and subunit gene expression in immature and adult male rats. Biology of reproduction. 1996;55(6):1377–82. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod55.6.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]