Abstract

Background

Infantile hemangiomas (IHs) are vascular tumors with potential for significant morbidities. There is a lack of validated objective tools to assess IH severity and response to treatment. Diffuse Optical Spectroscopy (DOS), a non-invasive, non-ionizing imaging modality can measure total hemoglobin concentration [THb] and tissue oxygen saturation (%StO2) to assess IH vascularity and response to treatment.

Objective

Our objective is to evaluate the utility of a wireless, handheld DOS system to assess IH characteristics at selected points during their clinical course.

Methods

Thirteen subjects (initial age 5.8±2.0 months) with fifteen IHs were enrolled. IHs were classified as proliferative, plateau-phase, or involuting. Nine patients with 11 IHs were untreated; four patients (with 4 IHs) were treated with timolol or propranolol. Each IH was evaluated by placing the DOS system directly on the lesion and a normal contralateral skin site. IH vascularity and oxygenation were scored by a newly defined Normalized Hypoxia Fraction coefficient. Measurements were recorded at intervals from initial visit to 1–2 years of age.

Results

For the 9 untreated IHs the NHF was highest at 6 months of age, during proliferation. Differences in NHFs between the proliferation and the plateau and involuting stages were statistically significant (p=0.02, p=0.0005). In treated patients, the NHF normalize up to 60% after 2 months. One treated IH came within 5% of the NHF for normal skin after 12 months.

Conclusions

Evidence is provided that DOS can be used to assess the vascularity and tissue oxygenation of IHs and monitor their progression and response to treatment.

Keywords: Laser, Hemangiomas, Vascular malformation

1. INTRODUCTION

Infantile hemangiomas (IHs) are the most common pediatric vascular tumors, affecting ~5% of infants (1, 2). Complications include ulceration, visual or airway obstruction, and potential for disfigurement (3). IH progression is documented using relatively subjective techniques relying upon physical examination, visual analog scale (VAS), and review of photographs (4–10). However, lesional measurements and color assessment can be inexact as the angle and lighting of photographs, and measurements are largely operator-dependent (5, 10). The lack of an objective and quantifiable tool to assess IH makes it difficult to decide on the correct course of lesion management and to compare the efficacies of different treatments. Additionally, it has been suggested that IHs are brought on by hypoxic stress of local skin tissue (1, 11) and a method of quantifying IH biology and severity could be useful in understanding the pathophysiological processes of IH, such as hypoxia or other mechanisms that may contribute to risk for ulceration (2, 12). Thus, it is of great interest to clinicians to develop and validate means for evidence based diagnostics (4, 13). Doppler ultrasound has been used to measure IH size, growth, blood flow, and vessel density (14, 15). However, its everyday clinical use is limited by the need for an experienced ultrasonographer and operator variability. The temperature difference between IH and surrounding or contralateral skin commonly observed makes infrared thermography (IRT) a viable solution for monitoring IH (16). However, results showed that IRT is less sensitive to deep IH.

To address this clinical need, we have developed a wireless handheld diffuse optical spectroscopy (WH-DOS) system. The system uses near-infrared (NIR) light to illuminate the IH and normal skin tissue and measures the light intensity that is re-emitted from the tissue. Since NIR light absorption is primarily affected by the concentration of oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin ([HbO2], [Hb]), these measurements can be used to derive the total-hemoglobin concentration ([THb]= [HbO2] + [Hb]), and oxygen saturation (StO2) within the microvasculature of superficial tissue. NIR light has no adverse health effects allowing for frequent measurements in patient monitoring, including pediatrics (17–19).

We employed our WH-DOS system in a longitudinal pilot study to evaluate its utility in IH vascularity assessment. We monitored changes in [THb] and StO2 over several timepoints up to 18 months in patients that were untreated or treated with propranolol or topical timolol. The DOS characteristics of IH in different stages (proliferation, plateau and involuting) and IH receiving treatment was correlated with clinical features.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Introduction and Clinical Examination

IRB approval was obtained from Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) IRB, and patients were recruited from the Pediatric Dermatology practices at CUMC. Infants were eligible if they were younger than 9 months at the time of initial visit and had at least one cutaneous IH greater than 2 cm in diameter in an area accessible by our probe’s 3×1cm measurement head. Frontal facial lesions were excluded. Patient’s eyes were shielded from the light using an NIR light absorbing material. Infants were scheduled to be assessed with the WH-DOS at the initial visit, at 2–4 months, and at 1–2 years follow-up visits.

Patients were assigned to the “natural history” cohort if no medical intervention was clinically indicated. Patients were enrolled in a “treatment” cohort when medical intervention was indicated with either oral propranolol or topical timolol. Prior to DOS measurements, subjects underwent clinical examination and photographic documentation. IH staging (proliferating, plateau, or involuting) and classification (superficial, deep, or mixed) was determined based on parental history of IH appearance, clinical and parental photos, patient age, and IH characteristics (e.g. color, texture) on physical exam at the time of assessment. The assessments were made at routine clinic visits by the same treating physician for continuity.

2.2. Study Device

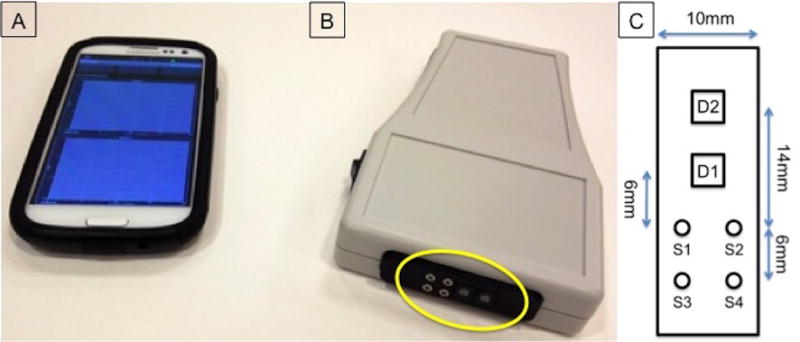

All patients were scanned with our enhanced WH-DOS system (Figure 1A,B), which is an optimized version of a previously presented device (20). The WH-DOS (Figure 1C) illuminates tissue using four near-infrared wavelengths of light and detects the re-emitted light intensities, which were entered into a reconstruction algorithm (20) to determine the functional parameters [HbO2] [Hb], [THb] and StO2 of the underlying tissue. The measurement probe was controlled via Bluetooth by a custom designed Android phone application.

Figure 1.

System for performing DOS measurements for infantile hemangiomas. (A) Smartphone with a custom-built phone application for system control. (B) Wireless handheld diffuse optical spectroscopy (WH-DOS) device with measurement head circled in yellow. (C) Diagram of measurement head with dimensions. S1–S4 represents light sources at 780, 905, 850, and 808nm. D1 and D2 represent the two detectors with a sensing area of 5.7mm2 used to capture back-reflected light from skin tissue.

The WH-DOS probe head was placed on the IH and on contralateral normal skin for measurements. If the IH lay in the center of the body, a normal skin measurement was performed a minimum of 5cm above or below the IH. Multiple measurements at different probe orientations were taken to ensure consistency of the measurement area. Individual measurements take only seconds; and the entire measurement procedure, including placement of the probe at multiple sites, can be performed in less than a minute. Functional parameters from multiple measurements were averaged prior to analysis.

2.3. Data Analysis

Since [THb] and StO2 may differ at different skin sites around the body, each IH measurement was normalized to the measurement performed at the contralateral normal tissue site to produce [THb] and %StO2 ratios:

| (1) |

The ratio rTHb provides a metric for volume measurement based on overall vascularity observed. For example, in bulkier, deep IHs compared to superficial IHs, one would expect higher values of rTHb. The ratio rStO2 provides a relative measure of the oxygen supply within the microvasculature between involved and uninvolved tissue.

The rTHb and rStO2 features may vary greatly depending on the subtype and staging, which could make it difficult to interpret the overall state of the IH. To quantify the overall state of the IH, we derived a third index that combines the two features with equal weight, which we call the Normalized Hypoxia Fraction (NHF):

| (2) |

This unitless index equally combines information about [THb] and StO2 into one number, since rTHb and rStO2 may change independently over time. This index, as we found, provides the best distinction between the proliferation, plateau, and involuting stages. As the IH evolves through these stages, rTHb and rStO2 will trend towards 1— suggesting that the vascular properties of the IH site is equivalent to that of the normal skin site. The three DOS derived parameters (rTHb, rStO2, and NHF) were correlated to the results of the clinical examination.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between patients in different stages of IH were made using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Holm-Sidak t-test was used to determine individual inter-group significance. Boxplots were generated for visualization of the range, shape, and skewness of data. Scatterplots showing normalization of NHF over time were produced. Repeatability of the system measurements was computed by measuring the coefficient of variance of [THb] and StO2 for each patient.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographics

Thirteen infants with fifteen hemangiomas were enrolled. All subjects were female. A summary of the enrolled patients is found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic features and clinical classifications for all subjects.

| Age (Months) | Classification (N) | Location (N) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial | Deep | Mixed | Trunk | Extremities | Head | ||

| All IH (N=15) | 5.8 ± 2.0 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 3 | 2 |

| Untreated IH (N=11) | 6 ± 11.9 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| Treated IH (N=4) | 3.8 ± 1.9 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

3.2. Untreated Infants with IH

We performed a total of 23 measurements on 13 untreated IHs including two pre-treatment measurements from two of the four treated infants for our analysis of untreated patients. Three IHs were scanned three times, five were scanned twice, and four were scanned once. Three measurements from two subjects were excluded due to user-error of the WH-DOS, which was discovered after the scans had been made. At time of measurements, the IHs were classified as being in the proliferation (N=6), plateau (N=12), or involuting stage (N=5) and correlated with patient age: the mean (SD) ages of subjects were 5.1 (±2.2), 9.1 (±2.3), and 14.0 (±7.9) months respectively.

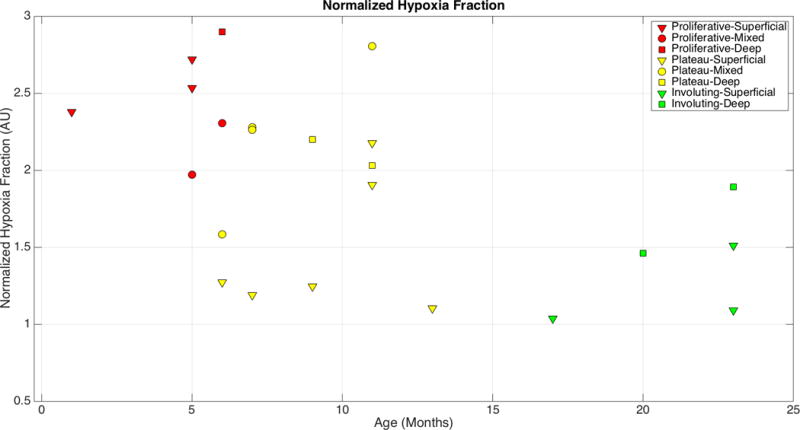

The NHF index peaked at 6 months of age (2.9) (Figure 2). NHF index decreased and trended towards normal skin over time. The NHF index for IHs with a deep component (deep or mixed IH) reached a minimum value of 1.46, while the NHF index of superficial IH reached a minimum value of 1.03, showing that no deep or mixed IH was fully involuted before the age of 23 months.

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of Normalized Hypoxia Fraction measurements of untreated subjects

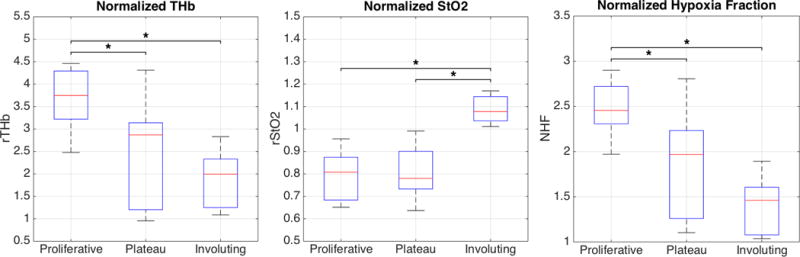

Overall, mean NHF indices decreased significantly as IHs progressed from proliferative to involuting (Figure 3, ANOVA, p = 0.002). Using the Holm-Sidak t-test, the NHF index during the proliferative stage was significantly higher than during the plateau and involuting stages (p=0.020, p=0.001 respectively). There was no significant difference in the NHF index between plateau and involuting stage IHs (p=0.121). A summary of the statistical results can be found in Table 2, which shows that NHF yields a better distinction than the measures of vascularity or oxygenation by themselves.

Figure 3.

Boxplots show the distribution of NHF measurements according to the stage classification: Proliferation (N=6), Plateau (N=12), and Involuting (N=5). One star (*) indicates statistical significance based on the Holm-Sidak t-test.

Table 2.

P-values of features comparing the three stages of IH (Proliferative, Plateau, and Involuting).

| Comparison (p-value) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature | Proliferative vs. Plateau | Plateau vs. Involuting | Proliferative vs. Involuting |

| rTHb | 0.0236* | 0.3355 | 0.0027* |

| rStO2 | 0.9343 | 0.0001* | 0.0010* |

| NHF | 0.0204* | 0.1206 | 0.0005* |

3.3. Treated Infants with IHs

Within the treatment subjects (N=4), 3 IHs were classified superficial and 1 as mixed. All subjects demonstrated response to propranolol treatment according to clinical criteria or size, volume, and color. Of the four infants, two did not have complete measurement data and were omitted from the analysis. From the remaining two subjects, one showed an improvement in the NHF index by 39.2% over a 3-month span of treatment with topical timolol.

The final subject (Figure 4) presented at 1 month of age with a large segmental superficial proliferative IH of the left lower extremity and was started on oral propranolol. Pre-treatment (1 month) and post-treatment (3 and 13 months) measurements were obtained from the IH and the contralateral, unaffected leg.

Figure 4.

Photographs of a subject classified with a large segmental superficial IH. Top, subject at 1 month of age, just prior to treatment. Middle, subject after 2 months of treatment. Bottom, subject after 12 months of treatment.

The baseline DOS measurements demonstrated hypoxia in the IH (NHF 2.38), which normalized to normal skin oxygenation (NHF 0.96) after 2 months of propranolol treatment. This correlated to clinical observations of decreased red discoloration and papules (Fig. 4, Table 1). After propranolol discontinuation at 13 months, NHF continued to be normal (0.97). These parameters suggest that total hemoglobin content was reduced while oxygen saturation in the IH increased towards normal skin values during propranolol treatment.

4. DISCUSSION

We have developed a WH-DOS device that provides an objective, reproducible, non-ionizing, non-invasive and portable tool to measure hemoglobin content and oxygen saturation in IHs of all stages without the need for sedation. By using these measures, DOS can tell us more about IH in its different stages and how the vascular information could be applicable towards understanding the pathophysiology.

Employing the WH-DOS, we have defined an NHF index as a measure of tissue hypoxia and vascularity that correlates well to clinical appearances and stages of IHs. NHF peaks at 6 months of age, correlating with the end of the most active proliferative period. By 13 months of age, a period of plateau phase, the NHF is steadily decreasing. This demonstrates the IH become more like normal skin as they mature and become less hypoxic. This might explain why IH become more likely to ulcerate during rapid growth periods (21). Furthermore, propranolol treatment normalized NHF at timepoints earlier than untreated IHs, suggesting that propranolol may target IHs in part by correction of the hypoxic state. This demonstrates that with successful treatment of IH, DOS may be able to track accelerating involution or movement towards normalization.

There are limits to this study. Although this system can be used for facial IH, we decided to take a conservative approach for ease of recruiting subjects given that greater ocular protection would be required to use the device on lesions closer to the eye. Use of protective goggles caused infants to become more active, and a result, repeatability measures faltered for these measurements. We did not use a formal visual analog scale (VAS) to assess patients at time points. US was only performed as clinically indicated and we do not have data for all patients. In cases in which US was performed the clinical classification (superficial versus having a deeper component) correlated with our clinical impression. Ulcerated IHs were excluded because the WH-DOS interface requires contact with the skin. Future versions of the WH-DOS could have a non-contact interface for measuring ulcerated lesions and improving repeatability.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that DOS has the potential to aid in monitoring IH growth and involuting stages, which may aid in management decision and quantify treatment efficacy. The high variability in the size and classification of IHs require more subjects for a more complete analysis. The treatment cohort was small and anecdotal and our findings need to be confirmed in a larger study. Future studies are required to evaluate DOS in relation to other objective measures of IH growth such as VAS and US, as well as to assess its applicability in complicated IHs.

Table 3.

Normalized [THb] StO2 and NHF results from the treated case subject. Measurements were made at 1 month of age just prior to treatment, and at 3 month and 13 months of age where propranolol was administered.

| Response to Propranolol: DOS Measurements | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month | 3 months | 13 months | |

| rTHb | 3.22 | 0.85 | 0.98 |

| rStO2 | 0.65 | 0.94 | 1.04 |

| NHF | 2.38 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Christopher Fong is supported by the National Science Foundation Integrative (NSF) Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship (IGERT) and a T32 grant (1T32AR059038-01A1) on Multidisciplinary Engineering Training in Musculoskeletal Research from National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01673971

Footnotes

COI: None declared

References

- 1.Drolet BA, Esterly NB, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas in Children. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:173–181. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907153410307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen TS, Eichenfield LF, Friedlander SF. Infantile Hemangiomas: An Update on Pathogenesis and Therapy. Pediatrics. 2013;131:99–108. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, Baselga E, Chamlin SL, Garzon MC, Horii KA, et al. Prospective Study of Infantile Hemangiomas: Demographic, Prenatal, and Perinatal Characteristics. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2007;150:291–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang LC, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, Baselga E, Chamlin SL, Garzon MC, et al. Growth Characteristics of Infantile Hemangiomas: Implications for Management. Pediatrics. 2008;122:360–367. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon JJ, James D, Fleming PJ, Kennedy CTC. A novel method for estimating the volume of capillary haemangioma to determine response to treatment. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:20–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.1997.2040617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haggstrom AN, Beaumont JL, Lai J, et al. Measuring the severity of infantile hemangiomas: Instrument development and reliability. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:197–202. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGrath PA, Seifert CE, Speechley KN, Booth JC, Stitt L, Gibson MC. A new analogue scale for assessing children’s pain: an initial validation study. Pain. 1996;64:435–443. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tollefson MM, Frieden IJ. Early Growth of Infantile Hemangiomas: What Parents’ Photographs Tell Us. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e314–e320. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tollefson MM, Frieden IJ. Early growth of infantile hemangiomas: what parents’ photographs tell us. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e314–320. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsang MW, Garzon MC, Frieden IJ. How to Measure a Growing Hemangioma and Assess Response to Therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:187–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleinman ME, Greives MR, Churgin SS, Blechman KM, Chang EI, Ceradini DJ, et al. Hypoxia-Induced Mediators of Stem/Progenitor Cell Trafficking Are Increased in Children With Hemangioma. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2664–2670. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.150284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drolet Ba FIJ. Characteristics of infantile hemangiomas as clues to pathogenesis: Does hypoxia connect the dots? Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1295–1299. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruckner AL, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:477–496. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drolet BA, Chamlin SL, Garzon MC, Adams D, Baselga E, Haggstrom AN, et al. Prospective Study of Spinal Anomalies in Children with Infantile Hemangiomas of the Lumbosacral Skin. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2010;157:789–794. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thoumazet F, Léauté-Labrèze C, Colin J, Mortemousque B. Efficacy of systemic propranolol for severe infantile haemangioma of the orbit and eyelid: a case study of eight patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:370–374. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohammed JA, Balma-Mena A, Chakkittakandiyil A, Matea F, Pope E. Infrared thermography to assess proliferation and involution of infantile hemangiomas: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:964–969. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toet MC, Lemmers PM. Brain monitoring in neonates. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Austin T, Gibson AP, Branco G, Yusof RM, Arridge SR, Meek JH, et al. Three dimensional optical imaging of blood volume and oxygenation in the neonatal brain. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1426–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ginther R, Sebastian VA, Huang R, Leonard SR, Gorney R, Guleserian KJ, et al. Cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy during cardiopulmonary bypass predicts superior vena cava oxygen saturation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142:359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flexman ML, Kim HK, Stoll R, Khalil MA, Fong CJ, Hielscher AH. A wireless handheld probe with spectrally constrained evolution strategies for diffuse optical imaging of tissue. Rev Sci Instrum. 2012;83:033108–033108. doi: 10.1063/1.3694494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, Nopper AJ, Antaya RJ, Cohen B, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Infantile Hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e1060–e1104. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]