Abstract

Genome-wide association studies in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases (AID) have uncovered hundreds of loci mediating risk. These associations are preferentially located in non-coding DNA regions and in particular in tissue-specific DNase I hypersensitivity sites (DHSs). While these analyses clearly demonstrate the overall enrichment of disease risk alleles on gene regulatory regions, they are not designed to identify individual regulatory regions mediating risk or the genes under their control, and thus uncover the specific molecular events driving disease risk. To do so we have departed from standard practice by identifying regulatory regions which replicate across samples and connect them to the genes they control through robust re-analysis of public data. We find significant evidence of regulatory potential in 78/301 (26%) risk loci across nine autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, and we find that individual genes are targeted by these effects in 53/78 (68%) of these. Thus, we are able to generate testable mechanistic hypotheses of the molecular changes that drive disease risk.

Keywords: genome-wide association study, non-coding variation, DNase I hypersensitivity site, fine-mapping

Introduction

The autoimmune and inflammatory diseases (AIDs) are a group of more than 80 common, complex diseases driven by systemic or tissue-specific immunological attack. This pathology is driven by loss of tolerance to self-antigens or chronic inflammatory episodes leading to long-term organ and tissue damage. Risk variants identified by genome-wide association studies (GWASs1, 2) are preferentially located in non-coding regions with tissue-specific chromatin accessibility3, 4, 5, 6 and in transcriptional enhancer regions active after T cell stimulation.7 Formal analyses partitioning the heritability of disease risk across different genomic regions support this enrichment,8 with excess heritability localizing to tissue-specific DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHSs).9 Cumulatively, these results suggest that AID pathology is mediated by changes to gene regulation in specific cell populations but are not designed to identify individual regulatory regions mediating risk or the genes under their control. Several fine-mapping efforts have jointly considered genetic association and epigenetic modification data as a way to identify causal variants.10, 11, 12 However, these efforts use epigenetic mark information to assess whether associated variants are likely to be causal, rather than to identify the regulatory sequences that mediate risk and the genes they affect.

We have therefore developed a systematic approach to identify regulatory regions mediating disease risk and thereby generate testable mechanistic hypotheses of the molecular changes that drive disease risk (Figure S1). For each association, we first calculate posterior probabilities of association from GWAS data and thence the set of markers forming the 99% credible interval (CI).13, 14, 15 We then overlap CI SNPs with DHSs in the region to identify which regulatory regions may harbor risk, and from these SNPs calculate the fraction of posterior probability attributable to each DHS. We chose DHSs as they are general markers of chromatin accessibility and typically only 150–390 base pairs long, compared to other histone modifications that can span tens to hundreds of kilobasepairs. Next, we identify genes controlled by each DHS by correlating chromatin accessibility state to expression levels of nearby genes.6, 16, 17 We use the atlas of tissues available at NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium (REMC) data,18, 19 where both DHSs and gene expression have been measured in the same samples. Finally, we combine the posterior probability of disease association of each DHS and the correlation between that DHS and the expression levels of nearby genes to calculate the probability that each gene is affected by the disease-mediating regulatory effect. We can thus estimate the probability that a gene influences disease risk.

Material and Methods

DNase I Hypersensitivity Data Peak-Calling, Clustering, and Quality Control

We obtained processed DNase I hypersensitivity (BED format) sequencing reads for 350 NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium (REMC) samples18, 19 corresponding to 73 cell types (see Web Resources). For each sample, we called 150 bp DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHSs) passing a 1% FDR threshold.20 We found 56 tissues with at least two replicates, which our statistical replication design requires, and limited our analysis to these (Table S1). Where more than two replicates were available, we chose the two replicates with the smallest Jaccard distance between their DHS peaks positions on the genome.

To identify corresponding DHSs across samples, we calculated the overlap between neighboring peaks across the 112 replicate samples as:

where Oi,j is the number of base pairs shared by DHSs i and j and li and lj are the length of DHSs i and j, respectively. We then grouped DHSs with a graph-based approach, the Markov clustering algorithm21 (MCL), using the default parameters, and defined the coordinates of a DHS cluster as the extreme positions covered by DHS peaks included in that cluster. Finally, we define each cluster as accessible in a sample if we observe at least one DHS peak within its boundaries in that sample (Figure S2).

Both peak calling and MCL clustering are naive to sample labels, so we can test for evidence that DHS clusters replicate in this analysis. We expect that DHS clusters representing true regulatory regions should be consistently accessible or unaccessible in replicate samples. We can thus calculate a replication statistic for DHS cluster d as:

where n1 is the number of cell types where DHS cluster d is active in both replicates; n2 is the number of cell types where the cluster is active in only one of the two replicates; and n3 is the number of cell types where the cluster is inactive in both replicates. For N = 56 tissues in our data, a = n1 / N, b = n2 / N, and c = n3 / N. Further, if r is the number of samples where DHS cluster is active, then p = r / (2 × N) and q is 1 − p. Note that we distinguish between the number of cell types (N = 56) and number of samples considered (2 × N = 112). We expect Sd to follow a distribution, and we selected DHS clusters passing a nominal significance threshold of pd ≤ 0.05, which we term replicable DHS. Overall, we found that replicable clusters tend to be active in more cell types and show a much higher level of concordance across replicate samples than those that do not replicate (Figure S3). To assess whether replicable DHSs capture the majority of disease-relevant signal, we compared the proportion of disease heritability (h2g) explained by all DHS-detected peaks in a tissue to that explained by the active replicable DHSs we annotated.8 For this we used genome-wide association summary statistics for MS22 and IBD.23 We note that replicable DHSs active in immune tissues cover a smaller percentage of the autosomal genome than those active in other tissues (Figure S4).

Credible Interval Mapping for Immunochip Loci

We obtained publicly available summary association statistics from case/control cohorts profiled on the Immunochip (Immunobase, see Web Resources; accessed May 2015) for autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD),24 celiac disease (CEL),25 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD),26 juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA),27 multiple sclerosis (MS),14 primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC),10 psoriasis (PSO),28 rheumatoid arthritis (RA),29 and type 1 diabetes (T1D)30 (Table 1). For each of these nine diseases, we compiled a list of genome-wide significant associations from the largest published GWASs.14, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 We then pruned this list of lead SNPs to include only those that overlap densely genotyped regions of Immunochip data and were present in the 1000 Genomes European ancestry cohorts.32 We excluded the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region on chromosome 6, where fine-mapping has been previously reported.4 As summary statistics for conditional associations are not available, we limited our analyses to primary reported signals in each disease.

Table 1.

Regulatory Fine-Mapping Resolves 78/301 Genome-Wide Significant Associations to Replicable DHSs and 53/78 to Single Genes across Nine Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases

| Disease |

Risk Loci |

Regulatory Potential ρ at 10% (5%) FDR |

Gene Pathogenicity γ at 10% (5%) FDR |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-wide Significant Association | ≥1 Credible SNP in a Replicable DHS | Loci with Significant ρ in ≥1 Cell Type | Number of DHSs Explaining ρ | Loci with Significant γ in ≥1 Cell Type | Genes with Significant γ in ≥1 Cell Type | |

| Autoimmune thyroid disease | 8 | 6 | 3 (1) | 10 (3) | 3 (0) | 8 (0) |

| Celiac disease | 31 | 28 | 2 (2) | 7 (7) | 2 (1) | 8 (4) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 125 | 97 | 19 (13) | 102 (76) | 12 (8) | 38 (18) |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | 22 | 17 | 9 (4) | 118 (58) | 5 (2) | 5 (2) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 54 | 48 | 25 (17) | 177 (118) | 17 (8) | 49 (15) |

| Primary biliary sclerosis | 15 | 12 | 2 (1) | 8 (6) | 2 (1) | 7 (2) |

| Psoriasis | 24 | 19 | 3 (1) | 26 (4) | 3 (1) | 7 (1) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 47 | 40 | 10 (8) | 158 (113) | 7 (5) | 20 (11) |

| Type 1 diabetes | 45 | 34 | 5 (4) | 18 (14) | 2 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Total | 371 | 301 | 78 (51) | 555 (350) | 53 (27) | 125 (45) |

We tabulated 371 previously reported genome-wide associations in loci densely covered by the Immunochip across nine diseases. From publicly available Immunochip summary statistics, we calculated credible interval SNP sets explaining 99% of the posterior probability of association. In 301/371 cases, we found at least one CI SNP overlapping a replicable DHS, and significant excess of posterior probability on replicable DHSs (regulatory potential ρ) in at least one of 22 Roadmap Epigenomics Project tissues in 78/301 cases. We were able to find significant evidence for individual genes in 53/78 loci. Overall, we prioritize 555 unique replicable DHS and 125 genes across 78 risk loci as likely to mediate disease risk.

We identified credible interval SNPs explaining 99% of the posterior probability of association for the remaining lead SNPs.13, 15 For each lead SNP, we identified SNPs within 2 Mb in linkage disequilibrium r2 ≥ 0.1 in the non-Finnish European 1000 Genomes reference panels.32 For each set S of these SNPs, we calculated posterior probabilities of association as

where is the Immunochip association chi-square test statistics of SNP i. We then selected the smallest number of SNPs required to explain 99% of the posterior probability. We note that this approach assumes that a single causal variant underlies the association and that it has been genotyped or imputed in the samples.

Calculating Regulatory Potential of Disease Loci

We first overlapped credible interval (CI) SNPs with our replicable DHSs, then computed the posterior probability of association attributable to each replicable DHS d in tissue t as

where PPs is the posterior probability of association for SNP s. Od(s) is equal to 1 if SNP s is located on replicable DHS d or the 100 bp flanking region each side of replicable DHS d, and it is 0 otherwise. Ad,t is 1 if DHS d is active in tissue t or 0 otherwise. For SNPs overlapping two or more replicable DHSs or their 100 bp flanking regions, we divided its posterior probability PPs between those replicable DHSs equally.

We then calculated the tissue-specific regulatory potential of each disease risk locus over D, the set of replicable DHSs active in tissue t as , and used a coordinate-shifting approach to assess significance empirically.3 In each of 40,000 permutations, we randomly re-assigned genomic coordinates to each replicable DHS within the locus, preserving its size and recalculated ρd,t, and calculated significance as the proportion of permutations that give values of ρd,t greater than the observed. We corrected for multiple testing in each disease using the false discovery rate.33

Finally, we then calculated the overall regulatory potential of each disease locus over all tissues as

To assess the statistical power of our framework, we performed a series of simulations where we specified either one or two causal variants in a locus (as previously described in Chun et al.34). In brief, we selected one REMC cell type, fetal kidney, from which to draw replicable DHS data for these simulations. We performed positive simulations where the causal variant is on a replicable DHS, and negative simulations where it is not. For two variants, we performed positive simulations where the first causal variant is on a replicable DHS and the second is not, and negative simulations where neither is on a replicable DHS (Figure S5).

Calculating Pathogenicity Factors of Association for Each Gene in a Risk Locus

There are 88 NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium (REMC) samples corresponding to 27 cell types profiled on the Affymetrix HuEx-1_0-st-v2 exon array, which we downloaded as raw CEL files (see Web Resources; accessed September 2013). We processed these data using standard methods available from the BioConductor project.35 In brief, we filtered cross-hybridizing probe sets, corrected background intensities with RMA, and quantile normalized the remaining probe set intensities across samples. We then collapsed probe sets to transcript-level intensities and mapped transcripts to genes using the current Gencode annotations for human genes (v.12), removing any transcripts without a single exact match to a gene annotation. We then identified the 22 tissues with matched DHS data (Table S1), averaged measurements over all replicates of each tissue, and quantile normalized the resulting dataset, comprising 13,822 transcripts mapping to 13,771 unique gene IDs.

We identified all genes within 1 Mb of the lead SNP for each locus, and for all replicable DHSs with (ρd > 0), computed the correlation between transcript levels and DHS accessibility across the 22 REMC tissues with a two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test w. To account for the correlation between gene expression levels, we assessed the significance of the rank sum test empirically. We removed the correlation induced both between genes and across tissues from the matrix of gene expression levels to (WPCA) using PCA whitening, which results in random variables with the same distributional characteristics as the original data. We then re-imposed the correlation structure due to related tissues on these random data by multiplying by the Cholesky decomposition of the gene expression covariance matrix (L), such that . GNull thus reflects the expected values of gene expression in the REMC tissues we analyzed if no replicable DHS affects expression. We then computed the Wilcoxon rank sum test statistic between each replicable DHS d and all genes of GNull. This formed our null Wilcoxon rank sum test statistics . From this null, we computed empirical p values as

where is the Wilcoxon rank sum test statistic between replicable DHS d and gene g, and denotes the number of events satisfying the enclosed criterion. This formulation accounts for the two-sided test and corrects for the inflation in caused by the correlation between tissues (Figure S6).

We next calculated per-gene g pathogenicity factor in tissue t as

where is the chi-square test statistic corresponding to the empirical correlation p value for replicable DHS d and gene g.

We assess the significance of by random permutation. In each locus, we establish how many replicable DHSs harbor CI SNPs, then construct the null distribution of by randomly selecting that number of replicable DHSs across the locus and recomputing . We calculated significance as the proportion of 50,000 permutations that give values of greater than the observed value, correcting for the number of genes within each locus with FDR.

Enrichment of Allele-Specific Accessibility, Tissue Specificity, and Functional Class for Replicable DHSs

We obtained a list of 362,284 SNPs overlapping DHS peaks in the Roadmap Epigenome Project data, which Maurano et al.36 tested for allele-specific DHS accessibility (ASA). Those authors found that 64,597/362,284 (18%) SNPs showed significant differences in accessibility at 5% FDR, giving us a genome-wide expectation for ASA. We then calculated whether credible interval SNPs overlapping DHSs from our analysis are more likely to show ASA than the genome-wide expectation, using Fisher’s exact test. Because some diseases have only a small number of loci associated at genome-wide significance, we pooled results across all nine AIDs for this analysis.

To test whether replicable DHSs harboring credible interval SNPs (burdened replicable DHSs) are preferentially active in each tissue, we compared the proportion of active burdened replicable DHSs to the proportion of all replicable DHSs active in that tissue with Fisher’s exact test. We used the same approach to determine enrichment for functional categories defined by ChromHMM37 and identified genomic functions of replicable DHSs through overlapping them with annotated ChromHMM regions (Figure S7).

Results

DHS peaks, as all epigenetic marks, are called in each sample separately.20 We therefore clustered DHS peaks to identify those corresponding to the same underlying regulatory site, so we could correlate accessibility state of the same site to gene expression data (Figure S2). In 56 REMC tissues with at least two replicate DHS sequencing runs, we called 22,060,505 narrow-sense 150 bp peaks at a false discovery rate FDR < 1%, which fell into 1,994,675 DHS clusters of 150–390 bp each, covering 14.8% of the autosomal genome (Figure S8). Of these, 1,079,138 (54.1%) covering 8.5% of the genome passed nominal significance in a statistical replication test ( test, p < 0.05). We found that common variants on this subset of peaks explains essentially all the heritability of both multiple sclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease that is captured by variants residing in the full set of DHS peaks, indicating that they represent the majority of regulatory regions relevant to AID risk (Figure S9). Of these 56 REMC tissues, 22 also have gene expression measurements, from which we calculated the correlation between accessibility state of 796,747 replicable DHSs active in at least one of these tissues, and transcript levels for 13,771 genes. As these represent a diverse sampling of organ systems, we avoid limiting our hypotheses to tissues previously suspected of driving pathogenesis while maximizing the sources of data we can utilize. We note our framework can be used with any regulatory feature and expression dataset and is publicly available (see Web Resources).

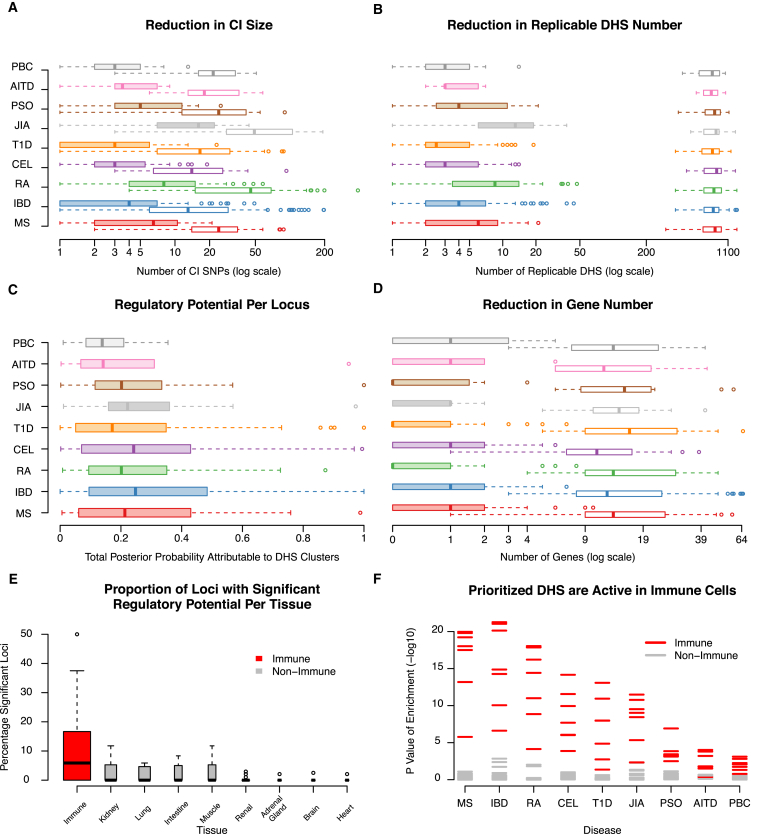

With this framework, we dissected 301 associations to one of nine AIDs, using publicly available summary association statistics from samples genotyped on the Immunochip, a targeted genotyping array from Immunobase38, 39 (see Web Resources; Table 1). These associations reside in loci genotyped at high density on the Immunochip so that common variants are completely ascertained, and have been previously reported at genome-wide significance.13, 14 We excluded the major histocompatibility locus, where complex LD patterns make credible interval mapping challenging.40 For each association, we calculated posterior probabilities of association for all markers and defined credible interval SNP sets.13, 15 We find a median of 4 (standard deviation, SD = 7.8) replicable DHSs overlap CI SNPs, out of a median 822 (SD = 205.2) replicable DHSs in each 2 Mb window around an association, indicating that this data integration step alone vastly reduces the number of potentially disease-relevant regulatory regions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Regulatory Fine-Mapping Identifies Specific Genes and Regulatory Regions Driving Risk in 301 Loci Associated to One of Nine Autoimmune Diseases

We combined credible interval (CI) mapping and DNase I hypersensitivity site (DHS) clustering in a statistical framework to identify GWAS loci where risk is likely to be mediated by variants in gene regulatory regions across nine autoimmune diseases (denoted by different colors). In those loci we then correlate the accessibility state of replicable DHSs with the expression of nearby genes to identify pathogenic genes.

(A) Only a subset of CI SNPs in each risk locus (open boxplots) are located on DHSs (filled boxplots).

(B) Only a small fraction of DHSs in each risk locus (open boxplots) harbor CI SNPs (filled boxplots).

(C) Most of the posterior probability of disease risk association (regulatory potential) is located on replicable DHSs, with 78/301 (26%) of loci showing significant enrichment of risk on DHSs (FDR 10%).

(D) By correlating DHS accessibility and gene expression, we find that only a subset of all genes in each locus (open boxplots) show significant probability of being regulated by risk variants (filled boxplots), with individual genes reaching significance in 53/78 (68%) of loci (FDR 10%).

(E) Immune cell subpopulations have a higher proportion of loci with risk localizing to active DHSs compared to tissues from other organ systems.

(F) DHSs harboring CI SNPs are more likely to be accessible in immune cell subpopulations than in other tissues. Overall, we find that 78/301 (26%) of loci associated to one of nine autoimmune diseases show significant evidence that risk is mediated by genetic variants on specific regulatory sequences.

To establish how likely each association is to be mediated by variation in regulatory regions, we compute their regulatory potential ρ, as the proportion of the posterior probability of association localizing to replicable DHSs. We then assess the significance of ρ by permutation, randomly reassigning the positions of all replicable DHSs in the locus.3 As most regulatory regions are active in only a subset of tissues, we do this for each REMC tissue independently, only considering the replicable DHSs active in that tissue. We find that 78/301 (26%) of loci show significant ρ in at least one REMC tissue at a false discovery rate (FDR) of 10% (51/301 at FDR 5%; Table 1). From simulations, we find that our method has good power to detect true cases of such regulatory potential, even in cases where two independent causal variants exist in a locus (Figure S5). Consistent with previous observations,4, 7, 41 we find that risk often localizes to replicable DHSs active in immune cell subpopulations (Figure 1), though the number of replicable DHSs active in these subpopulations is small (Figure S10). We reasoned that if replicable DHSs harboring CI SNPs actually mediate risk, their accessibility state should be perturbed by the variants they harbor36 and they should be accessible in disease-relevant cell populations. We find that, as a group, CI SNPs on DHSs are more likely to be associated to allele-specific accessibility than non-CI SNPs on replicable DHSs (Fisher exact test p = 7 × 10−6) and that this enrichment is consistent across minor allele frequency bins (Figure S11). We also found that replicable DHSs harboring CI SNPs are more likely to be accessible in immune cell subpopulations (Figure 1). These results show that our approach identifies regulatory regions affected by variants likely to influence disease risk, supporting the view that alteration of gene regulatory region accessibility is a major mechanism of disease risk.

Having validated that our analysis was identifying genuine regulatory risk effects, we next turned to identifying specific disease-mediating replicable DHSs and the genes they control in the 78 loci with significant ρ (FDR < 0.1; Tables 1, S2, and S3). We found that a median of three replicable DHSs (SD = 4.6) account for >90% of the total association posterior attributable to all replicable DHSs in these loci, a phenomenon independent of the total regulatory potential in a locus (Figure S12). This indicates that we can resolve most loci to a small number of candidate regulators. To identify the genes likely to mediate pathogenesis in each locus, we correlated the accessibility state (open or closed) of each replicable DHS to the expression levels of nearby genes. As we found wide-spread correlation between replicable DHS accessibility and gene expression (a median of 353/822 replicable DHSs per locus, at a correlation p < 0.05, Figure S13), we explicitly tested the evidence that each gene is excessively correlated to risk-mediating replicable DHSs as the pathogenicity factor γ. As with ρ, we establish the significance of γ in each tissue by permutation. We find at least one significant gene in at least one tissue in 53/78 loci (FDR < 0.1), indicating that we can identify the likely targets of the regulatory regions represented by these replicable DHSs (summarized in Figure 1 and Table 1, with detailed entries in Table S3). Surprisingly, these genes are not the closest to the most associated variant in 38/53 (72%) of cases, and in 45/53 (85%) were not the closest gene to the replicable DHS with the highest regulatory potential, suggesting that risk-relevant regulatory regions exert influence over genes at considerable distances (Table S3). The replicable DHSs with significant ρ values are more likely to be marked as active enhancers of transcription, further supporting this conclusion (Figure S7). In the 25/73 loci where we could not identify a gene target, we found that the replicable DHSs with the highest ρ are not correlated to any gene in the REMC data (Figure S14), suggesting they either affect genes not captured there or represent regulatory regions with different functions.

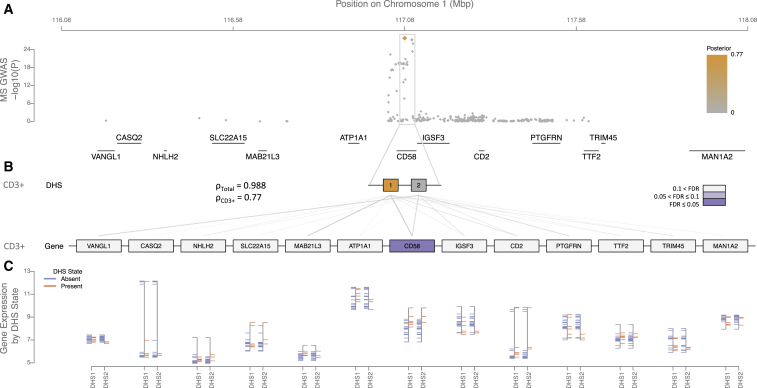

In several cases, we found evidence supporting a previous hypothesis for a causal gene in a locus. For example, an association to multiple sclerosis (MS) risk on chromosome 1 shows significant regulatory potential in T cells and macrophages. This is driven by CI SNPs on two replicable DHSs, both of which implicate CD58 (Figure 2). CD58 encodes lymophocyte-function associated antigen 3 (LFA3), a co-stimulatory molecule expressed by antigen-presenting cells, mediating their interaction with circulating T cells by binding lymophocyte-function associated antigen 2 (LFA2).42 The latter is encoded by the CD2 immediately proximal to CD58 but does not show strong evidence of control by risk-mediating replicable DHSs. The protective MS effect in this region is associated with an increase in CD58 expression, leading to an up-regulation of the transcription factor FoxP3 via CD2. This results in enhanced functioning of CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells, thought to be defective in MS-affected individuals.42 Similarly, we find significant evidence for EOMES and SLC4A7 regulation in CD3+ T cells for another MS association on chromosome 3 (Figure S15) and IRF8 regulation across immune cell subpopulations for a rheumatoid arthritis (RA) association on chromosome 16 (Figure S16).

Figure 2.

Regulatory Fine-Mapping Identifies Two Replicable DHSs and Changes to CD58 Regulation in CD3+ T Cells as Mediating Multiple Sclerosis Risk on Chromosome 1

A genome-wide significant association on chromosome 1 localizes to the CD58 locus (A), and 98.8% of the posterior probability of association (orange) localizes to replicable DHSs in the locus (B). Different combinations of replicable DHSs are active in each of the Roadmap Epigenomics Project tissues we examined; the enrichment is most significant in replicable DHSs active in CD3+ T cells (77% of the overall posterior probability; FDR < 0.1). The expression levels of each gene in the locus can be correlated to the accessibility state of each replicable DHS (gray lines). By partitioning the posterior probability of association attributable to each replicable DHS by the strength of this correlation, we find that CD58 shows significant enrichment (purple, FDR < 0.05). The expression level of CD58 is markedly higher in tissues where the replicable DHSs we identify are accessible (orange) than in tissues where they are inaccessible (blue; C).

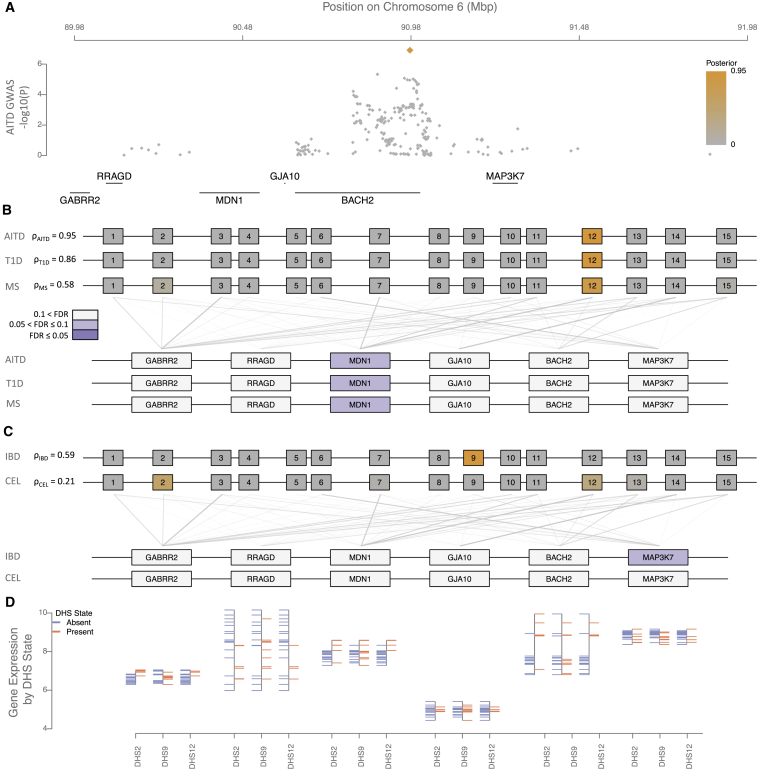

Many Immunochip loci harbor associations to multiple diseases, suggesting that a portion of risk is shared.43, 44 Consistent with this observation, we found that 42 Immunochip loci had nominally significant ρ for at least one cell type for more than one disease, representing 107 of the 301 initially considered associations. Of these, 25/42 loci showed regulatory potential in two AIDs, and twelve, four, and a single locus showed regulatory potential in three, four, and five AIDs, respectively. Due to the correlation imposed by linkage disequilibrium, it remains challenging to conclude that associations to different traits in the same locus represent a true shared effect, where the same underlying causal variant drives risk for multiple diseases.45 We therefore sought to establish whether associations to different diseases in these 42 loci identify the same replicable DHSs and prioritize the same genes, and we found striking examples of shared and distinct effects across these 42 loci. For example, five diseases show genetic association to a region of chromosome 6, with the most significant SNPs residing in the coding region of BACH2 (Figure 3). We found significant regulatory potential in T cell subsets for autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD), MS, and type 1 diabetes (T1D), which independently localize to the same replicable DHS in the three diseases. We found weaker evidence for regulatory potential in both celiac disease (CEL) and IBD across most immune tissues, with the IBD evidence also supporting a role for major organs including the intestine. These results are nominally significant but do not pass our FDR threshold in either disease. In the first three diseases, we can independently prioritize a single gene, MDN1, as the most likely target gene for these effects, with no significant evidence for BACH2. In contrast, we found no significant evidence for any gene in either CEL or IBD, despite the credible intervals for these diseases essentially overlapping those for AITD, MS, and T1D (Figure 3). We note that the most associated SNPs for MS, AITD, and T1D are the same (rs72928038), and the r2 between this SNP and the most associated SNPs of IBD (rs1847472) and CEL (rs7753008) are 0.34 and 0.25, respectively. Similarly, a region on chromosome 1 harbors associations to both IBD and T1D. We found significant regulatory potential in CD3+ T cells for both diseases, and independently prioritize a single gene, IL19, as the most likely target for these effects (Figure S17).We are thus able to begin resolving associations across multiple diseases into shared and distinct effects in the same locus.

Figure 3.

Regulatory Fine-Mapping on Chromosome 6 Identifies a Single Replicable DHS and Changes to MDN1 Regulations, not BACH2, in CD3+ T Cells, as Driving Risk to Autoimmune Thyroid Disease, Multiple Sclerosis, and Type 1 Diabetes

Association to five autoimmune diseases localizes to the coding region of BACH2 (autoimmune thyroid disease in A; others are shown in Figure S19). We found significant regulatory potential in CD3+ T cell subsets for autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD), multiple sclerosis (MS), and type 1 diabetes (T1D), which independently localize to the same replicable DHS in the three diseases (B). In each case, we can independently prioritize a single gene, MDN1, as most likely target gene for these effects, with no significant evidence for BACH2. We found weaker evidence for regulatory potential in both celiac disease (CEL) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) across most immune tissues, including CD3+ T cells (C), which stems from two different replicable DHSs than the signal in AITD, MS, and T1D. This evidence does not pass our FDR threshold in either disease. In neither case do we find any evidence to support either MDN1 or BACH2 in these diseases. The expression level of MDN1 is markedly higher in tissues where the three replicable DHSs we identify are accessible (orange) than in tissues where they are inaccessible (blue; D).

To more generally assess how our approach resolves shared associations, we compared the overlaps between most associated markers, credible interval sets, replicable DHSs harboring CI variants, and genes identified across the 42 loci (Table 2). We found more overlap than expected by chance for each comparison (hypergeometric p ≪ 0.001), indicating that both genetic association data and regulatory region data point toward shared effects. Furthermore, we found that the extent of this overlap increased as we moved from comparing lead SNPs to prioritized replicable DHSs and genes (Fisher exact test between proportion of lead SNPs and prioritized genes p = 5 × 10−6). This increase in concordance holds true when we consider only the 25 loci harboring two disease associations, indicating that our conclusions are not based on biases in a minority of loci harboring many associations (Table S4). We found that the rate of prioritized gene overlap is correlated to linkage disequilibrium between lead variants, suggesting that though GWASs may not identify precisely the same variant in two separate diseases, shared effects can clearly be identified by considering the likely functional effects in a locus (Figure S18). Overall, we find significant evidence for at least one gene across multiple diseases in 17/42 loci, and these are the same genes in 12/17. We find that this is due to overlapping replicable DHSs identified across diseases in 11/12 of these cases, suggesting that the same mechanistic effect drives risk to multiple diseases. Thus, our approach can uncover biological pleiotropy46 across diseases even when the identity of the causal variant remains unknown, beyond the comparison of credible interval sets.

Table 2.

Regulatory Fine-Mapping Indicates Risk Variants for Multiple Diseases in the Same Loci Affect the Same Genes

| Concordance | Discordance | Jaccard Coefficient | Disease Overlap (Fisher’s Exact p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of most associated SNPs | 9 | 86 | 0.09 | – (p = NA) |

| Number of CI SNPs (mean) | 9.26 | 41.14 | 0.2 | 2.15 (p = 0.0134) |

| Number of prioritized CI SNPs (mean) | 2.67 | 11.37 | 0.23 | 2.25 (p = 0.0104) |

| Number of prioritized replicable DHSs (mean) | 2.62 | 9.84 | 0.24 | 2.54 (p = 0.0031) |

| Number of prioritized genes (mean) | 1.29 | 2.32 | 0.46 | 5.27 (p = 5 × 10−6) |

In loci harboring associations to multiple diseases, we find that the most associated variants are often different (top row). However, the credible interval sets in these loci overlap significantly (hypergeometric p < 0.001, second row), and this overlap is greater than that of the most associated variants alone (Fisher’s exact test p shown in the last column). This overlap is also true when comparing the subset of CI SNPs on DHSs and for the number of DHSs harboring a CI SNP across diseases (third and fourth rows). When we compare prioritized genes, we see further increase in overlap relative to most associated variants and to prioritized DHSs (bottom row, Fisher’s exact test p = 5 × 10−6 and p = 4.9 × 10−4, respectively). Thus, identifying risk-mediating genes partially overcomes the limited resolution of analyses only focusing on genetic association data.

Discussion

We have described an approach to detect gene regulatory regions driving disease risk and through them, the genes likely to mediate pathogenesis, through robust re-analysis of public data. We find substantial evidence of regulatory potential in a substantial proportion of loci across nine AIDs and we resolve these to individual genes in 53/78 (68%) controlled by regulatory regions active in immune cells. In loci with no substantial evidence of regulatory potential, we suggest that the risk effect is mediated either by coding variation47 or by regulatory regions in immune cell subpopulations and physiological contexts not adequately represented in the REMC datasets. Thus, as profiles for more cell types and physiological contexts are collected, we expect not only that more AID loci may yield to such dissection, but that traits and diseases for which data on the relevant tissues are not presently available may also be interrogated. Some portion of these loci may also harbor multiple independent causal variants with equivalent effect sizes, which erode our power to detect regulatory potential even when one of these causal variants is located on a regulatory region. We note that our approach will also apply to summary statistics from densely imputed genome-wide genotyping platforms, though care should be taken when comparing results across studies as we do in the present report, as differences in imputation strategies may induce false positives and negatives to such comparisons.

Our approach generates specific hypotheses about pathobiology that are often beyond what is currently known. Our dissection of the BACH2 locus, for instance, implicates MDN1 as the likely causal gene. MDN1 encodes midasin AAA ATPase 1, a nuclear chaperone required for maturation and export of pre-60S ribosome units. It is widely expressed in the immune and hematopoietic systems and elsewhere. Homozygous knockout mice do not survive, but heterozygote animals have not been screened for immune-relevant phenotypes.48 Variation at the MDN1 locus across inbred mouse strains is associated with total lymphocyte count, CD4+ T cell viability in response to doxycycline E, and CD4+ T cell levels as a proportion of total lymphocyte count, suggesting an overall effect on CD4+ T cell viability.49, 50 In humans, the gene is highly intolerant to mutation51 and particularly to loss-of-function mutations,52 suggesting a fundamental role. We therefore suggest that MDN1 may drive pathogenesis by altering CD4+ T cell homeostasis and viability in adults. We note that, despite the experimental evidence supporting this role, this gene has not yet received significant consideration in human disease studies, highlighting the importance of unbiased, data-driven approaches in gene prioritization.

Another gene we prioritize, IL19, encodes the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin 19, a member of the IL10 family. IL19 activates STAT3 signaling in monocytes and through this drives the production of IL6 and TNFα to induce apoptosis in T cells. Decreased IL19 expression exacerbates disease in murine experimental colitis, a model for human IBD where pathology is driven by T helper cell-mediated immune responses,53, 54 and IL19 is overexpressed in IBD-affected individuals with active disease.55 Thus, IL19 appears to mediate pathogenesis by decreasing innate immune dampening of adaptive responses and is of significant therapeutic interest.56

In the majority of the 53 loci in which we are able to resolve to a gene, we do not prioritize the gene closest to the maximally associated marker. This suggests that risk-mediating regulatory elements act at considerable distances, either by influencing the overall transcriptional landscape of the region or by acting on individual genes at a distance.57 These competing explanations make different predictions: the former implies that many genes will be controlled by the risk-mediating regulator, whereas the latter predicts a limited number of targets. As we find only a single significant gene in the majority of cases, our results support the latter scenario, where risk is mediated by changes to specific gene regulatory programs affecting particular genes.

More broadly, the observation that most common, complex disease risk aggregates in gene regulatory regions4, 7, 9 has made the translation of genetic association results into molecular and cellular mechanisms challenging. Fine-mapping is limited in resolution by linkage disequilibrium, making association data alone insufficient to identify a causal variant driving risk in a locus. For example, in a recent Immunochip study of multiple sclerosis,14 we were able to reduce 14/66 (21%) Immunochip regions to 90% credible interval sets of fewer than 15 variants, and 5/66 to fewer than 5 variants, though increases in sample size will raise the resolution of these approaches.15 These fine-mapping strategies assume that a single causal variant drives risk in the locus, which conditional analyses in both the MS and IBD data suggest holds true.14, 15 Unlike coding variants, inferring function of non-coding polymorphisms remains challenging, though efforts to integrate functional genomics and population genetics data into composite functional scores58, 59 or integrating genetic and epigenetic data11 are gaining some traction on this problem. Our own work complements these efforts by focusing on identifying individual regulators and the genes they control to generate testable hypotheses of the molecular basis of disease mechanism.

Acknowledgments

C.C. and P.S. were partly supported by a shared research agreement with Biogen, which had no role in designing or interpreting this study. We are grateful to the International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium and the International Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics Consortium, and specifically to Mark Daly and Stephan Ripke, for access to GWAS summary statistics from their respective meta-analyses. We are also grateful to Benjamin Neale and Hillary Finucane for assistance with heritability calculations, and to Sung Chun for assistance with simulations.

Published: July 6, 2017

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include 19 figures and 4 tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.06.001.

Web Resources

Immunobase, https://www.immunobase.org/

Roadmap chromatin accessibility data, https://www.genboree.org/EdaccData/Current-Release/experiment-sample/Chromatin_Accessibility/

Roadmap exon array data, http://www.genboree.org/EdaccData/Current-Release/experiment-sample/Expression_Array/

Supplemental Data

A total of 1954 replicable DHS (1470 unique) harbor at least one credible interval SNP. The last column gives the total posterior probability attributable to all SNPs on each replicable DHS (though the vast majority have exactly one SNP).

For each disease, we give the most associated SNP, the exact coordinates of each locus, the number of replicable DHS, credible interval (CI) SNPs, and genes in the locus, the total number of DHS harboring a CI SNP, and the total regulatory potential (ρ) attributable to all these replicable DHS. Then, for each locus, we show each Roadmap Epigenome Mapping Consortium tissue with significant excess of regulatory potential (FDR < 0.1), indicating the total number of replicable DHS in the locus active in the tissue, the number of these harboring CI SNPs, the sum of ρ they account for, and the p value of the enrichment test. Finally, within each of these tissues, we show each gene with significant pathogenicity factor (FDR < 0.1) with the accompanying p value.

References

- 1.Zhernakova A., van Diemen C.C., Wijmenga C. Detecting shared pathogenesis from the shared genetics of immune-related diseases. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:43–55. doi: 10.1038/nrg2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zenewicz L.A., Abraham C., Flavell R.A., Cho J.H. Unraveling the genetics of autoimmunity. Cell. 2010;140:791–797. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trynka G., Sandor C., Han B., Xu H., Stranger B.E., Liu X.S., Raychaudhuri S. Chromatin marks identify critical cell types for fine mapping complex trait variants. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:124–130. doi: 10.1038/ng.2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maurano M.T., Humbert R., Rynes E., Thurman R.E., Haugen E., Wang H., Reynolds A.P., Sandstrom R., Qu H., Brody J. Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science. 2012;337:1190–1195. doi: 10.1126/science.1222794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karczewski K.J., Dudley J.T., Kukurba K.R., Chen R., Butte A.J., Montgomery S.B., Snyder M. Systematic functional regulatory assessment of disease-associated variants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:9607–9612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219099110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corradin O., Saiakhova A., Akhtar-Zaidi B., Myeroff L., Willis J., Cowper-Sal lari R., Lupien M., Markowitz S., Scacheri P.C. Combinatorial effects of multiple enhancer variants in linkage disequilibrium dictate levels of gene expression to confer susceptibility to common traits. Genome Res. 2014;24:1–13. doi: 10.1101/gr.164079.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farh K.K., Marson A., Zhu J., Kleinewietfeld M., Housley W.J., Beik S., Shoresh N., Whitton H., Ryan R.J., Shishkin A.A. Genetic and epigenetic fine mapping of causal autoimmune disease variants. Nature. 2015;518:337–343. doi: 10.1038/nature13835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finucane H.K., Bulik-Sullivan B., Gusev A., Trynka G., Reshef Y., Loh P.R., Anttila V., Xu H., Zang C., Farh K., ReproGen Consortium. Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. RACI Consortium Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:1228–1235. doi: 10.1038/ng.3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gusev A., Lee S.H., Trynka G., Finucane H., Vilhjálmsson B.J., Xu H., Zang C., Ripke S., Bulik-Sullivan B., Stahl E., Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. SWE-SCZ Consortium. Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. SWE-SCZ Consortium Partitioning heritability of regulatory and cell-type-specific variants across 11 common diseases. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;95:535–552. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J.Z., Almarri M.A., Gaffney D.J., Mells G.F., Jostins L., Cordell H.J., Ducker S.J., Day D.B., Heneghan M.A., Neuberger J.M., UK Primary Biliary Cirrhosis (PBC) Consortium. Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 3 Dense fine-mapping study identifies new susceptibility loci for primary biliary cirrhosis. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:1137–1141. doi: 10.1038/ng.2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kichaev G., Pasaniuc B. Leveraging functional-annotation data in trans-ethnic fine-mapping studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;97:260–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaub M.A., Boyle A.P., Kundaje A., Batzoglou S., Snyder M. Linking disease associations with regulatory information in the human genome. Genome Res. 2012;22:1748–1759. doi: 10.1101/gr.136127.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maller J.B., McVean G., Byrnes J., Vukcevic D., Palin K., Su Z., Howson J.M., Auton A., Myers S., Morris A., Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Bayesian refinement of association signals for 14 loci in 3 common diseases. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:1294–1301. doi: 10.1038/ng.2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beecham A.H., Patsopoulos N.A., Xifara D.K., Davis M.F., Kemppinen A., Cotsapas C., Shah T.S., Spencer C., Booth D., Goris A., International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium (IMSGC) Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 (WTCCC2) International IBD Genetics Consortium (IIBDGC) Analysis of immune-related loci identifies 48 new susceptibility variants for multiple sclerosis. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1353–1360. doi: 10.1038/ng.2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang H., Fang M., Jostins L., Mirkov M.U., Boucher G., Anderson C.A., Andersen V., Cleynen I., Cortes A., Crins F. Association mapping of inflammatory bowel disease loci to single variant resolution. bioRxiv. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nature22969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheffield N.C., Thurman R.E., Song L., Safi A., Stamatoyannopoulos J.A., Lenhard B., Crawford G.E., Furey T.S. Patterns of regulatory activity across diverse human cell types predict tissue identity, transcription factor binding, and long-range interactions. Genome Res. 2013;23:777–788. doi: 10.1101/gr.152140.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thurman R.E., Rynes E., Humbert R., Vierstra J., Maurano M.T., Haugen E., Sheffield N.C., Stergachis A.B., Wang H., Vernot B. The accessible chromatin landscape of the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:75–82. doi: 10.1038/nature11232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernstein B.E., Stamatoyannopoulos J.A., Costello J.F., Ren B., Milosavljevic A., Meissner A., Kellis M., Marra M.A., Beaudet A.L., Ecker J.R. The NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:1045–1048. doi: 10.1038/nbt1010-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kundaje A., Meuleman W., Ernst J., Bilenky M., Yen A., Heravi-Moussavi A., Kheradpour P., Zhang Z., Wang J., Ziller M.J., Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 2015;518:317–330. doi: 10.1038/nature14248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.John S., Sabo P.J., Thurman R.E., Sung M.H., Biddie S.C., Johnson T.A., Hager G.L., Stamatoyannopoulos J.A. Chromatin accessibility pre-determines glucocorticoid receptor binding patterns. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:264–268. doi: 10.1038/ng.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enright A.J., Van Dongen S., Ouzounis C.A. An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1575–1584. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patsopoulos N.A., Esposito F., Reischl J., Lehr S., Bauer D., Heubach J., Sandbrink R., Pohl C., Edan G., Kappos L., Bayer Pharma MS Genetics Working Group. Steering Committees of Studies Evaluating IFNβ-1b and a CCR1-Antagonist. ANZgene Consortium. GeneMSA. International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies novel multiple sclerosis susceptibility loci. Ann. Neurol. 2011;70:897–912. doi: 10.1002/ana.22609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J.Z., van Sommeren S., Huang H., Ng S.C., Alberts R., Takahashi A., Ripke S., Lee J.C., Jostins L., Shah T., International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium. International IBD Genetics Consortium Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:979–986. doi: 10.1038/ng.3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper J.D., Simmonds M.J., Walker N.M., Burren O., Brand O.J., Guo H., Wallace C., Stevens H., Coleman G., Franklyn J.A., Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Seven newly identified loci for autoimmune thyroid disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:5202–5208. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trynka G., Hunt K.A., Bockett N.A., Romanos J., Mistry V., Szperl A., Bakker S.F., Bardella M.T., Bhaw-Rosun L., Castillejo G., Spanish Consortium on the Genetics of Coeliac Disease (CEGEC) PreventCD Study Group. Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium (WTCCC) Dense genotyping identifies and localizes multiple common and rare variant association signals in celiac disease. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:1193–1201. doi: 10.1038/ng.998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jostins L., Ripke S., Weersma R.K., Duerr R.H., McGovern D.P., Hui K.Y., Lee J.C., Schumm L.P., Sharma Y., Anderson C.A., International IBD Genetics Consortium (IIBDGC) Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491:119–124. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hinks A., Cobb J., Marion M.C., Prahalad S., Sudman M., Bowes J., Martin P., Comeau M.E., Sajuthi S., Andrews R., Boston Children’s JIA Registry. British Society of Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology (BSPAR) Study Group. Childhood Arthritis Prospective Study (CAPS) Childhood Arthritis Response to Medication Study (CHARMS) German Society for Pediatric Rheumatology (GKJR) JIA Gene Expression Study. NIAMS JIA Genetic Registry. TREAT Study. United Kingdom Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Genetics Consortium (UKJIAGC) Dense genotyping of immune-related disease regions identifies 14 new susceptibility loci for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:664–669. doi: 10.1038/ng.2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsoi L.C., Spain S.L., Knight J., Ellinghaus E., Stuart P.E., Capon F., Ding J., Li Y., Tejasvi T., Gudjonsson J.E., Collaborative Association Study of Psoriasis (CASP) Genetic Analysis of Psoriasis Consortium. Psoriasis Association Genetics Extension. Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 Identification of 15 new psoriasis susceptibility loci highlights the role of innate immunity. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:1341–1348. doi: 10.1038/ng.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okada Y., Wu D., Trynka G., Raj T., Terao C., Ikari K., Kochi Y., Ohmura K., Suzuki A., Yoshida S., RACI consortium. GARNET consortium Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis contributes to biology and drug discovery. Nature. 2014;506:376–381. doi: 10.1038/nature12873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onengut-Gumuscu S., Chen W.M., Burren O., Cooper N.J., Quinlan A.R., Mychaleckyj J.C., Farber E., Bonnie J.K., Szpak M., Schofield E., Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium Fine mapping of type 1 diabetes susceptibility loci and evidence for colocalization of causal variants with lymphoid gene enhancers. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:381–386. doi: 10.1038/ng.3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cordell H.J., Han Y., Mells G.F., Li Y., Hirschfield G.M., Greene C.S., Xie G., Juran B.D., Zhu D., Qian D.C., Canadian-US PBC Consortium. Italian PBC Genetics Study Group. UK-PBC Consortium International genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new primary biliary cirrhosis risk loci and targetable pathogenic pathways. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8019. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abecasis G.R., Altshuler D., Auton A., Brooks L.D., Durbin R.M., Gibbs R.A., Hurles M.E., McVean G.A., 1000 Genomes Project Consortium A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. Royal Stat. Soc. B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chun S., Casparino A., Patsopoulos N.A., Croteau-Chonka D.C., Raby B.A., De Jager P.L., Sunyaev S.R., Cotsapas C. Limited statistical evidence for shared genetic effects of eQTLs and autoimmune-disease-associated loci in three major immune-cell types. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:600–605. doi: 10.1038/ng.3795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huber W., Carey V.J., Gentleman R., Anders S., Carlson M., Carvalho B.S., Bravo H.C., Davis S., Gatto L., Girke T. Orchestrating high-throughput genomic analysis with Bioconductor. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:115–121. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maurano M.T., Haugen E., Sandstrom R., Vierstra J., Shafer A., Kaul R., Stamatoyannopoulos J.A. Large-scale identification of sequence variants influencing human transcription factor occupancy in vivo. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:1393–1401. doi: 10.1038/ng.3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ernst J., Kellis M. ChromHMM: automating chromatin-state discovery and characterization. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:215–216. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cortes A., Brown M.A. Promise and pitfalls of the Immunochip. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011;13:101. doi: 10.1186/ar3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parkes M., Cortes A., van Heel D.A., Brown M.A. Genetic insights into common pathways and complex relationships among immune-mediated diseases. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14:661–673. doi: 10.1038/nrg3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moutsianas L., Jostins L., Beecham A.H., Dilthey A.T., Xifara D.K., Ban M., Shah T.S., Patsopoulos N.A., Alfredsson L., Anderson C.A., International IBD Genetics Consortium (IIBDGC) International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium Class II HLA interactions modulate genetic risk for multiple sclerosis. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:1107–1113. doi: 10.1038/ng.3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trynka G., Westra H.J., Slowikowski K., Hu X., Xu H., Stranger B.E., Klein R.J., Han B., Raychaudhuri S. Disentangling the effects of colocalizing genomic annotations to functionally prioritize non-coding variants within complex-trait loci. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;97:139–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Jager P.L., Baecher-Allan C., Maier L.M., Arthur A.T., Ottoboni L., Barcellos L., McCauley J.L., Sawcer S., Goris A., Saarela J. The role of the CD58 locus in multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:5264–5269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813310106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ellinghaus D., Jostins L., Spain S.L., Cortes A., Bethune J., Han B., Park Y.R., Raychaudhuri S., Pouget J.G., Hübenthal M., International IBD Genetics Consortium (IIBDGC) International Genetics of Ankylosing Spondylitis Consortium (IGAS) International PSC Study Group (IPSCSG) Genetic Analysis of Psoriasis Consortium (GAPC) Psoriasis Association Genetics Extension (PAGE) Analysis of five chronic inflammatory diseases identifies 27 new associations and highlights disease-specific patterns at shared loci. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:510–518. doi: 10.1038/ng.3528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cotsapas C., Voight B.F., Rossin E., Lage K., Neale B.M., Wallace C., Abecasis G.R., Barrett J.C., Behrens T., Cho J., FOCiS Network of Consortia Pervasive sharing of genetic effects in autoimmune disease. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bulik-Sullivan B.K., Loh P.R., Finucane H.K., Ripke S., Yang J., Patterson N., Daly M.J., Price A.L., Neale B.M., Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:291–295. doi: 10.1038/ng.3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Solovieff N., Cotsapas C., Lee P.H., Purcell S.M., Smoller J.W. Pleiotropy in complex traits: challenges and strategies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14:483–495. doi: 10.1038/nrg3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dendrou C.A., Cortes A., Shipman L., Evans H.G., Attfield K.E., Jostins L., Barber T., Kaur G., Kuttikkatte S.B., Leach O.A. Resolving TYK2 locus genotype-to-phenotype differences in autoimmunity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016;8:363ra149. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skarnes W.C., Rosen B., West A.P., Koutsourakis M., Bushell W., Iyer V., Mujica A.O., Thomas M., Harrow J., Cox T. A conditional knockout resource for the genome-wide study of mouse gene function. Nature. 2011;474:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petkova S.B., Yuan R., Tsaih S.W., Schott W., Roopenian D.C., Paigen B. Genetic influence on immune phenotype revealed strain-specific variations in peripheral blood lineages. Physiol. Genomics. 2008;34:304–314. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00185.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frick A., Fedoriw Y., Richards K., Damania B., Parks B., Suzuki O., Benton C.S., Chan E., Thomas R.S., Wiltshire T. Immune cell-based screening assay for response to anticancer agents: applications in pharmacogenomics. Pharm. Genomics Pers. Med. 2015;8:81–98. doi: 10.2147/PGPM.S73312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petrovski S., Wang Q., Heinzen E.L., Allen A.S., Goldstein D.B. Genic intolerance to functional variation and the interpretation of personal genomes. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lek M., Karczewski K.J., Minikel E.V., Samocha K.E., Banks E., Fennell T., O’Donnell-Luria A.H., Ware J.S., Hill A.J., Cummings B.B., Exome Aggregation Consortium Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matsuo Y., Azuma Y.T., Kuwamura M., Kuramoto N., Nishiyama K., Yoshida N., Ikeda Y., Fujimoto Y., Nakajima H., Takeuchi T. Interleukin 19 reduces inflammation in chemically induced experimental colitis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015;29:468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Azuma Y.T., Matsuo Y., Kuwamura M., Yancopoulos G.D., Valenzuela D.M., Murphy A.J., Nakajima H., Karow M., Takeuchi T. Interleukin-19 protects mice from innate-mediated colonic inflammation. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1017–1028. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fonseca-Camarillo G., Furuzawa-Carballeda J., Granados J., Yamamoto-Furusho J.K. Expression of interleukin (IL)-19 and IL-24 in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a cross-sectional study. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2014;177:64–75. doi: 10.1111/cei.12285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Azuma Y.T., Nakajima H., Takeuchi T. IL-19 as a potential therapeutic in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011;17:3776–3780. doi: 10.2174/138161211798357845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davison L.J., Wallace C., Cooper J.D., Cope N.F., Wilson N.K., Smyth D.J., Howson J.M., Saleh N., Al-Jeffery A., Angus K.L., Cardiogenics Consortium Long-range DNA looping and gene expression analyses identify DEXI as an autoimmune disease candidate gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:322–333. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kircher M., Witten D.M., Jain P., O’Roak B.J., Cooper G.M., Shendure J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:310–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Petrovski S., Gussow A.B., Wang Q., Halvorsen M., Han Y., Weir W.H., Allen A.S., Goldstein D.B. The intolerance of regulatory sequence to genetic variation predicts gene dosage sensitivity. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A total of 1954 replicable DHS (1470 unique) harbor at least one credible interval SNP. The last column gives the total posterior probability attributable to all SNPs on each replicable DHS (though the vast majority have exactly one SNP).

For each disease, we give the most associated SNP, the exact coordinates of each locus, the number of replicable DHS, credible interval (CI) SNPs, and genes in the locus, the total number of DHS harboring a CI SNP, and the total regulatory potential (ρ) attributable to all these replicable DHS. Then, for each locus, we show each Roadmap Epigenome Mapping Consortium tissue with significant excess of regulatory potential (FDR < 0.1), indicating the total number of replicable DHS in the locus active in the tissue, the number of these harboring CI SNPs, the sum of ρ they account for, and the p value of the enrichment test. Finally, within each of these tissues, we show each gene with significant pathogenicity factor (FDR < 0.1) with the accompanying p value.