Abstract

PURPOSE

Harms of prostate cancer (PCa) treatment on urinary HRQOL have been amply studied. We sought to evaluate not only harms, but also potential benefits of PCa treatment on relieving pre-treatment urinary symptom burden.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In American (n = 1021) and Spanish (n = 539) multicenter prospective cohorts of men with localized PCa, we evaluated effects of radical prostatectomy (RP), external radiotherapy (XRT), or brachytherapy (BT), on relieving pre-treatment urinary symptoms, and on inducing urinary symptoms de novo, measured by changes in urinary medication usage and patient-reported urinary bother.

RESULTS

Urinary symptom burden improved in 23%, and worsened in 28% of subjects after PCa treatment in the American cohort. Pre- and 2 years post-treatment urinary medication usage rates were 15% and 6% for RP, 22% and 26% for XRT, and 19% and 46% for BT. Pre-treatment urinary medication usage (OR 1.4 [95% CI 1.0–2.0], p=0.04) and pre-treatment moderate LUTS (OR 2.8 [95% CI 2.2–3.6]) predicted PCa treatment-associated relief of baseline urinary symptom burden. Subjects with pre-treatment LUTS who underwent RP experienced the greatest relief of pre-treatment symptoms (OR 4.3 [95% CI 3.0–6.1]), despite deleterious de novo urinary incontinence in some men. The magnitude of pre-treatment urinary symptom burden and benefit of cancer treatment on those symptoms were verified in the Spanish cohort.

CONCLUSIONS

Men with pre-treatment LUTS may experience benefit, rather than harm, in overall urinary outcome from primary PCa treatment. Practitioners should consider the full spectrum of urinary symptom burden evident before PCa treatment in treatment decisions.

INTRODUCTION

Definitive treatment for localized prostate cancer often occurs in an age distribution of men in whom pre-existing lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) from benign prostatic hyperplasia or the local effects of prostate cancer are already a significant health problem1–3. Most analyses, however, do not account for baseline urinary health-related quality of life (HRQOL), and focus purely on the negative effects of treatment, failing to consider the full spectrum of potential post-treatment changes in urinary symptom burden, including the possibility of symptom relief.

While several prospective multicenter studies have investigated the effects of prostate cancer treatment on urinary HRQOL4–10, few have examined urinary medication usage and/or urinary procedural interventions, and most have focused on urinary incontinence as their primary outcome. The relative degree to which patients are bothered by urinary incontinence and LUTS is unclear. Outcomes are often reported as changes in mean HRQOL scores across treatment groups, which favors a “one size fits all” approach that obscures the diversity of individual changes within treatment groups, i.e., who is getting worse, staying the same, or getting better. Achievement of patient-centered care and individualized adjustment of urinary outcome expectations require an understanding of how a patient’s pre-treatment HRQOL and other factors may influence his potential for symptom worsening or symptom relief after treatment11.

We previously described a multicenter, prospective study evaluating HRQOL outcomes after RP, XRT, and BT12. In order to better understand which patients experience a worsened, unchanged, or improved urinary symptom burden after prostate cancer treatment, and the relative impact of urinary incontinence and LUTS, we re-evaluated this cohort after all participants had completed at least 2 years of follow-up and described urinary medication usage, urinary procedural interventions, and changes in overall urinary symptom burden, using ordinal logistic regression to identify significant predictors of urinary outcome changes after prostate cancer treatment.

METHODS

Study Subjects

The Prostate Cancer Outcomes and Satisfaction with Treatment Assessment (PROST-QA) cohort consists of 1,201 men with previously untreated stage T1 to T2 prostate cancer and were enrolled from 2003–2006 at 9 university-affiliated hospitals into an institutional review board-approved protocol after providing written informed consent. We analyzed the 1,021 cohort participants that had complete 2-year urinary HRQOL follow-up, which included 522 RP, 239 XRT, and 260 BT subjects.

Treatment

RP was performed with the use of open retropubic (n=335) or laparoscopic/robotic techniques (n=187)13–15; 92% of patients received unilateral or bilateral nerve-sparing. Among men who underwent XRT, 84% had intensity-modulated RT (remainder had conformal beam) and 31% had neoadjuvant hormonal therapy. BT was performed transperineally with permanent low-dose rate isotopes (typically I-125)12. Adjuvant/salvage hormonal therapy rates within 2 years were low (<5%).

Outcome Measures

Patient-reported outcomes were collected prospectively by a third-party phone-survey facility before treatment through 2 years post-treatment. We measured urinary incontinence using the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26)16 and LUTS using both EPIC-26 and the AUA Symptom Index (AUA-SI1). We measured subjects’ global urinary symptom burden with the EPIC-26 overall urinary bother question: “Overall, how much of a problem has your urinary function been for you?” measured on a five-point Likert scale (no problem to big problem).

Case report forms collected pre- and post-treatment urinary medication usage and the incidence of urinary procedural interventions. Urinary procedural interventions were categorized as: 1) urinary reconstruction, e.g., artificial urinary sphincter, male urinary sling, urethroplasty, 2) hospitalization for urinary complication, 3) endoscopic/minimally invasive intervention with intent to repair/diagnose a urinary complication, 4) any urinary catheterization, and 5) diagnostic cystoscopy. An adjudication panel comprised of a non-treating urologist and radiation oncologist blinded to treatment type determined procedural category. The principal investigator resolved lack of consensus. Subjects with multiple interventions of the same category were counted once; those with interventions in different categories were counted once per category. We classified urinary medications as alpha-blockers, 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, and anti-cholinergics; pre-treatment medications excluded prophylactic initiation of alpha-blockers immediately prior to BT.

Statistical Considerations

We used longitudinal logistic regression with generalized estimating equations (GEE) to compare use of urinary medications among groups over time, and logistic regression to compare incidence of urinary interventions among groups.

Within each treatment group, we examined how each individual subject’s overall symptom burden changed from pre-treatment to 2-years post-treatment. To capture both the magnitude and direction of change, we categorized this bother change into a five-item ordinal scale: “−2”: major worsening, “−1”: minor worsening, “0”: no change, “1”: minor improvement, and “2”: major improvement, where “minor” = 1 point and “major” = 2 or greater point change. We used ordinal logistic regression to identify factors that predicted a higher ordinal score across all levels of urinary bother change (i.e., a “more favorable” or “less unfavorable” change in urinary symptom burden). The following covariates were considered: age, race, cohabitation, education level, comorbidities, body mass index, D’Amico risk group17, prostate size, pre-treatment use of urinary medications, pre-treatment LUTS, and pre-treatment incontinence. We used backward elimination to identify the variables retained in the multivariable model, with an inclusion threshold of p<0.10. We tested for interaction between treatment group and the strongest outcome predictor.

External Validation

The Multicentric Spanish Group of Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer10, henceforth referred to as the “Spanish cohort,” served as an external validation cohort. Of the 614 subjects that completed 2 year follow-up and met the Spanish cohort’s original inclusion and exclusion criteria, 539 had the equivalent demographic and HRQOL information from pre-treatment to 2 years post-treatment that was examined in the PROST-QA analysis. Several covariates, including medication use, were not available for comparison. To determine whether the factors predictive of urinary outcome change would replicate in an independent cohort, we performed ordinal logistic regression as described above.

RESULTS

We describe treatment group characteristics in Table 1, and previously described detailed trends in urinary HRQOL between pre-treatment to 2-years post-treatment12. Pre-treatment incontinence was rare (Table 2). Pre-treatment moderate to severe LUTS was common throughout the cohort (37%), least common in BT subjects (29%).

Table 1.

Pre-treatment Patient and Disease Characteristics in the PROST-QA Cohort

| RP (n=522) | XRT (n=239) | BT (n=260) | All (n=1021) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment – median (IQR)* | 60 (56–65) | 69 (63–74) | 66 (61–71) | 63 (58–69) |

| Race – no. (%)* | ||||

| African-American | 25 (5) | 34 (14) | 28 (11) | 87 (9) |

| Other | 497 (95) | 205 (86) | 232 (89) | 934 (91) |

| BMI (kg/m2) – median (IQR) | 27 (25–30) | 28 (25–31) | 28 (25–31) | 28 (25–31) |

| Cohabitation – no. (%)* | 456 (87) | 187 (78) | 207 (80) | 850 (83) |

| Number of comorbidities – no. (%)* | ||||

| 0–1 | 402 (77) | 144 (60) | 172 (66) | 718 (70) |

| 2 | 82 (16) | 58 (24) | 59 (23) | 199 (19) |

| 3+ | 38 (7) | 37 (15) | 29 (11) | 104 (10) |

| Prostate volume (mL) -- median (IQR)* | 40 (30–52) | 42 (30–59) | 36 (28–47) | 39 (30–53) |

| PSA (ng/mL) – median (IQR)* | 5.5 (4.2 – 7.5) | 6.3 (4.3 – 9.7) | 5.2 (4.2 – 6.8) | 5.5 (4.2 – 7.8) |

| Clinical T-stage – no. (%)* | ||||

| cT1 | 374 (72) | 164 (69) | 214 (82) | 752 (74) |

| cT2 | 148 (28) | 75 (31) | 46 (18) | 269 (26) |

| Gleason Score on initial biopsy– no. (%)* | ||||

| 6 or less | 316 (61) | 105 (44) | 199 (77) | 620 (61) |

| 7 | 181 (35) | 100 (42) | 60 (23) | 341 (33) |

| 8–10 | 25 (5) | 34 (14) | 1 (0) | 60 (6) |

| D’Amico risk17 group* | ||||

| Low | 275 (53) | 84 (35) | 184 (71) | 543 (53) |

| Intermediate | 205 (39) | 106 (44) | 72 (28) | 383 (38) |

| High | 42 (8) | 49 (21) | 4 (2) | 95 (9) |

RP=radical prostatectomy; XRT=external beam radiation; BT=brachytherapy; IQR=interquartile range; BMI=body mass index; PSA=prostate-specific antigen

Treatment groups differed in distributions of age, race, marital/living status, number of comorbidities, prostate volume, PSA, clinical stage, Gleason score, and D’Amico risk group (each P<0.01)12

Table 2.

Pre-treatment and 2-year Post-treatment Urinary HRQOL, Urinary Medication Usage, and Post-treatment Urinary Procedural Intervention in the PROST-QA Cohort

| RP (n=522) | XRT (n=239) | BT (n=260) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatment | 2 years | Pre-treatment | 2 years | Pre-treatment | 2 years | |

| EPIC-2616 Urinary incontinence score – mean ± SD | 94 ± 13 | 80 ± 23 | 93 ± 13 | 89 ± 16 | 94 ± 11 | 88 ± 19 |

| No/very small problem with leakage of urine – no. (%) | 490 (94) | 384 (73) | 222 (93) | 198 (83) | 248 (95) | 214 (82) |

| Small problem with leakage of urine – no. (%) | 23 (4) | 98 (19) | 13 (5) | 32 (13) | 10 (4) | 29 (11) |

| Moderate-big problem with leakage of urine – no. (%) | 9 (2) | 40 (8) | 4 (2) | 9 (4) | 2 (1) | 17 (7) |

| EPIC-26 Urinary irritation/obstruction score–mean±SD | 87 ± 15 | 92 ± 11 | 87 ± 13 | 89 ± 14 | 90 ± 12 | 84 ± 17 |

| AUA Symptom Index (AUA-SI) score1 – no. (%)* | ||||||

| Mild (0–7) | 314 (60) | 145 (61) | 186 (72) | |||

| Moderate (8–19) | 173 (33) | 87 (36) | 70 (27) | |||

| Severe (20–35) | 35 (7) | 7 (3) | 4 (1) | |||

| Patients requiring urinary medications – no. (%) | ||||||

| Any urinary medication** | 76 (15) | 32 (6) | 52 (22) | 55 (26) | 50 (19) | 109 (46) |

| Alpha-blocker | 66 (13) | 9 (2) | 38 (16) | 50 (23) | 38 (15) | 103 (43) |

| 5-AR inhibitor | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 3 (1) | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Anticholinergic | 4 (1) | 23 (5) | 3 (1) | 10 (5) | 1 (0) | 22 (9) |

| Need for urinary procedural intervention† – no. (%) | ||||||

| All urinary procedural interventions‡ | -- | 36 (7) | -- | 13 (5) | -- | 25 (10) |

| Urinary reconstructive procedures | 8 (2) | 2 (1) | 1 (0) | |||

| Hospitalization for urinary complication | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | |||

| Endo/perc intervention/stricture diagnosis | 18 (3) | 3 (1) | 6 (2) | |||

| Unplanned urinary catheterization | 11 (2) | 2 (1) | 15 (6) | |||

| Diagnostic cystoscopy without stricture | 11 (2) | 7 (3) | 12 (5) | |||

| Overall urinary bother - no. (%) | ||||||

| No problem | 296 (56) | 290 (55) | 120 (50) | 128 (53) | 158 (60) | 117 (45) |

| Very small problem | 95 (18) | 121 (23) | 62 (26) | 51 (21) | 58 (22) | 54 (21) |

| Small problem | 74 (14) | 75 (14) | 33 (14) | 37 (15) | 24 (9) | 52 (20) |

| Moderate problem | 49 (9) | 27 (5) | 24 (10) | 20 (8) | 16 (6) | 28 (11) |

| Big problem | 8 (2) | 9 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 4 (2) | 9 (3) |

RP = Radical Prostatectomy, XRT = External Radiotherapy, BT = Brachytherapy

Pre-treatment LUTS as measured by AUA-SI was significantly different between treatment groups (p < 0.01)

Changes between pre-treatment and 2 years were significant for RP and BT (each p < 0.001). Differences in 2-year medication usage at 2 years was significant between groups (p < 0.001)

Between 6 months and 2-years post-treatment, except for urinary reconstructive procedure, which was assessed between treatment start and 2-years. Patients listed only once in each category

No statistically significant differences in procedural intervention between treatment groups (p = 0.20)

RP subjects had a clinically significant18 decrease (worsening) in mean EPIC-26 incontinence score (−14±24 points; p<0.001), and a clinically significant increase in mean EPIC-26 irritation/obstruction score (improved LUTS) 2 years post-treatment (5±15; p<0.001). BT subjects had clinically significant worsening of both mean incontinence (−6±19 points; p<0.001) and irritation/obstruction (−6±18; p<0.001) scores between pre- and 2-years post-treatment.

Urinary medication usage and urinary procedural intervention

The pre-treatment rate of urinary medication use differed among groups (p=0.03), lowest among RP subjects. The proportion of RP subjects requiring urinary medications decreased significantly from pre- (15%) to post-treatment (6%). Of the 76 RP subjects taking a pre-treatment urinary medication, 84% were able to discontinue the medication; 28% started a new medication, most commonly an anticholinergic (Supplemental Table 1). Urinary medication usage was unchanged after XRT (26% vs. 22% pre-treatment). After BT, urinary medication usage increased significantly (46% vs. 19% pre-treatment; p<0.001), with 43% of patients taking alpha-blockers at 2 years compared to 14% pre-treatment. 75 (36%) of the BT subjects who were not taking urinary medications pre-BT started and remained on a new urinary medication at 2 years post-BT (Supplemental Table 1).

The rate of procedural intervention for post-treatment urinary complications was not statistically significantly different between treatment groups (p=0.20; Table 2). Most urinary reconstructive procedures were performed in the RP group; the BT group had the highest proportion of men receiving unplanned urethral catheterizations and diagnostic cystoscopies.

Changes in overall urinary symptom burden

We examined how subjects’ global perception of their urinary symptom burden (overall urinary bother), changed from pre- to 2 years post-treatment (Supplemental Tables 2 through 5). For the entire cohort, 23% reported improvement and 28% reported worsening of urinary problems. The RP and XRT treatment groups each had approximately equal proportions of subjects perceiving urinary improvement and worsening (28% and 27% for RP; 25% and 24% for XRT, respectively). The proportion of RP subjects with moderate to severe urinary bother decreased from 11% to 7% after treatment (p = 0.01) despite worse overall incontinence. This proportion was unchanged in XRT subjects, and significantly increased in BT subjects (8% pre-BT vs 14% post-BT; p = 0.005), who were more likely to have worsened urinary problems 2 years post-treatment (37% worsened, 12% improved).

We then performed multivariable ordinal logistic regression to identify pre-treatment factors predictive of favorable pre- to post-treatment change in overall urinary symptom burden over a five-point ordinal scale from major worsening to major improvement (Table 3). For all treatment groups, the most powerful positive predictor of favorable (or less unfavorable) change in urinary bother was the presence of moderate to severe (AUA-SI ≥ 8) pre-treatment LUTS (OR 2.8; 95% CI 2.2 – 3.6; p < 0.001). Pre-treatment urinary medication usage was also a significant positive predictor (OR 1.4; 95% CI 1.0 – 2.0; p = 0.04). Baseline incontinence was not significant (p = 0.4).

Table 3.

Association of Individual Patient Factors with Odds of Favorable Change in Overall Urinary Bother from Pre- to 2 years Post-Treatment after Primary Prostate Cancer Treatment*

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatment urinary medication usage | 1.4 | 1.0 – 2.0 | 0.04 |

| Moderate to severe pre-treatment LUTS† | 2.8 | 2.2 – 3.6 | <0.001 |

| In RP subjects | 4.3 | 3.0 – 6.1 | <0.001 |

| In XRT subjects | 1.9 | 1.1 – 3.0 | 0.01 |

| In BT subjects | 1.9 | 1.1 – 3.1 | 0.01 |

| Pre-treatment urinary incontinence†† | 1.2 | 0.8 – 1.7 | 0.39 |

| Cohabitation | 0.8 | 0.6 – 1.0 | 0.07 |

| 2 or more comorbidities | 0.8 | 0.6 – 1.1 | 0.13 |

| Body mass index > 35 | 0.7 | 0.5 – 1.0 | 0.08 |

The Odds Ratios were computed based by the multivariable ordinal logistic regression model as described in Methods. The following covariates were also assessed, but were not statistically significant, nor suspected to be confounders: age, cohabitation, race, education, D’Amico risk group, prostate size, and use of hormonal therapy. Potential confounders were retained the model, even if not statistically significant.

Defined as AUA-SI1 score ≥ 8. Effect modification was present between moderate-severe pre-treatment LUTS and treatment group (p = 0.003). The reported odds ratio of 2.8 is without an interaction term present.

Defined as EPIC-26 urinary incontinence score ≤ 70

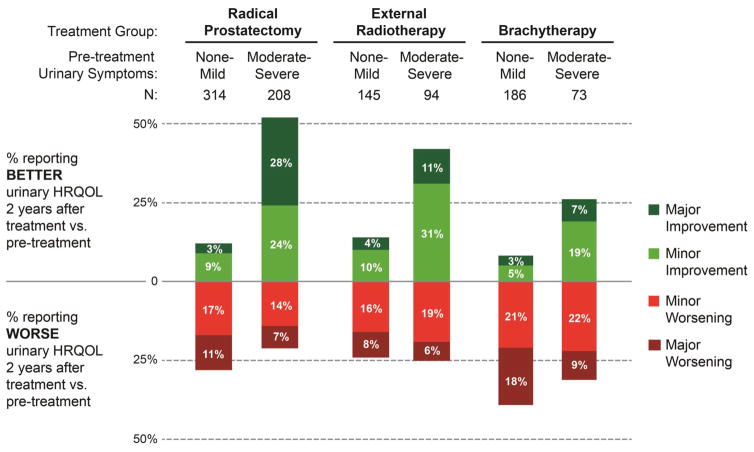

There was significant effect modification between the most powerful outcome predictor (baseline LUTS) and treatment group (p = 0.003; Table 3). This was especially pronounced in RP subjects, in whom having pre-treatment LUTS conferred a greater than four times higher odds of urinary symptom relief from pre- to post-treatment (OR 4.3, 95% CI 3.0 – 6.1; p < 0.001). This interaction between treatment group and pre-treatment LUTS is illustrated in Figure 1. 52% of RP subjects with pre-treatment LUTS reported improvement in their urinary bother post-treatment; 21% reported worsening. Of the 52 (10%) RP subjects with both pre-treatment LUTS and urinary medication usage, 76% (48% major, 28% minor) reported improvement after RP (Supplemental Table 6). In BT subjects, more patients with pre-existing LUTS worsened than improved after treatment (31% and 26%, respectively).

Figure 1. Ordinal Change in Overall Urinary Bother from Pre-Treatment to 2 Years Post-Treatment in the PROST-QA Cohort.

Ordinal change in overall urinary bother was measured as change in subject response to the overall urinary bother item (originally from the UCLA-Prostate Cancer Index and conserved in the EPIC-26 HRQOL instrument16) from pre-treatment to 2 years post-treatment, because this item reflects burden of obstructive urinary symptoms as well as urinary incontinence. Pre-treatment obstructive urinary symptoms were measured using the AUA Symptom Index1 (0–7 = mild symptoms, 8–14 = moderate symptoms, and 15–35 = severe symptoms. “Minor” refers to a one point change on the UCLA-PCI overall urinary bother item likert response scale (e.g. patient response as having “small problem” changed to “moderate problem”, or “moderate problem” to “big problem,” or vice versa), and “Major” refers to a two or more point change in overall urinary bother. Percentages in each bar do not add up to 100% because the remaining subjects in each category had no change in urinary symptom burden between pre-treatment and 2-years post-treatment.

We found similar findings on analysis of a separate, previously described Spanish cohort (Supplemental Table 7). On ordinal logistic regression, pre-treatment LUTS was the most significant predictor of favorable change in overall urinary bother (OR = 1.7; p = 0.01), and there was significant interaction between this effect and treatment group (p = 0.01). The effect of pre-treatment LUTS on favorable urinary bother change was again most prominent in RP subjects (OR = 4.15; p < 0.001), but non-significant for XRT and BT subjects (OR = 0.85 and 1.66, respectively; p > 0.05).

Relative impact of urinary incontinence and irritation/obstruction

We then investigated the relative effects of incontinence and irritation/obstruction on overall urinary bother by further evaluating the RP subjects who reported pre-treatment moderate to severe LUTS (Table 4). Most subjects whose post-RP urinary incontinence was mild (0–1 pads/day) preferred their post-treatment urinary state to their pre-treatment state (63% of patients reported improvement, 10% worsened), while severe incontinence (3+ pads/day) negated any relief gained from LUTS improvement. Overall urinary bother for all subjects was more closely correlated with urinary irritation/obstruction score (Spearman correlation = 0.70) than urinary incontinence score (Spearman correlation = 0.55).

Table 4.

Effect of Post-Treatment Urinary Incontinence Severity on Ordinal Change in Overall Urinary Bother in Radical Prostatectomy Subjects with Moderate to Severe Pre-treatment LUTS (AUA-SI1 ≥ 8; n = 207)

| −2 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | N (% of total) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Incontinence Pads/Day | ||||||

| 0 | 2% | 1% | 27% | 26% | 44% | 82 (40) |

| 1 | 8% | 11% | 28% | 25% | 28% | 53 (26) |

| 2 | 6% | 32% | 25% | 25% | 13% | 53 (26) |

| 3+ | 32% | 26% | 21% | 16% | 5% | 19 (10) |

“−2” = Major (2 or more point) worsening, “−1” = Minor (1 point) worsening, 0 = no change, “1” = Minor (1 point) improvement, “2” = Major (2 or more point) improvement in overall urinary bother from pre- to 2 years post-treatment.

DISCUSSION

The deleterious effects of prostate cancer treatment on urinary function have been studied extensively5, 19–22. Our study highlights the prevalence and importance of burdensome pre-treatment urinary problems in men with prostate cancer, and further examines how treatment-induced changes affect patients’ urinary quality of life, an inherently subjective concept that incorporates patients’ individual perceptions of their problems and the efforts required to mitigate them.

LUTS were a substantial pre-treatment problem in this cohort: 37% had AUA-SI scores that indicated moderate to severe symptoms, and 17% were on pre-treatment urinary medications. This prevalence is comparable to that seen in similarly aged men without prostate cancer in population-based cohorts2,3, and is less than men undergoing observation for early-stage prostate cancer, in which 49% reported moderate to severe symptoms23.

To our knowledge, this is the first multicenter prospective study to report the pre- and post-treatment rate of urinary medication usage. Urinary medications may not only influence the urinary HRQOL domain scores, but themselves constitutes an often unmeasured quality of life and cost burden, as medications being taken two years post-treatment are likely needed lifelong. Our findings suggest those studies which report urinary problems after BT occurring primarily in the acute setting24–26 may fail to account for the increase in alpha blocker use from pre- (14%) to post-treatment (43%), and likely underestimating the long-term effects of treatment.

A Swedish randomized trial comparing RP to watchful waiting found in a cross-sectional analysis that a smaller proportion of men experienced post-treatment obstructive LUTS after RP than watchful waiting, but was limited by the lack of pre-treatment urinary HRQOL assessment23. Several other studies have suggested urinary obstruction relief after RP27–29, but neither identified individual characteristics predisposing to favorable outcome, nor assessed urinary medication usage. Most studies report outcomes as changes in mean function scores, which can mask changes for individual subjects within treatment groups. Stratification by pre-treatment function can help elucidate individual changes, as suggested in a single-center study11.

We chose to further investigate changes in subjects’ global perceptions of their urinary symptom burden by examining overall urinary bother, which encompasses both urinary incontinence and irritation/obstruction. By analyzing this outcome in a novel, ordinal fashion, we captured the full spectrum of potential changes in urinary quality of life, including the direction (worsening vs improved) and degree (major vs minor) of HRQOL change. Our use of ordinal logistic regression allowed us to identify pre-treatment LUTS as a factor that should not be ignored when counseling patients on what to expect for their urination after treatment.

Urinary incontinence was a substantial enough problem after RP that over 20% of subjects with pre-treatment LUTS reported worse overall urinary problems after surgery despite the potential for LUTS relief. Previous urinary HRQOL studies that have examined both urinary function and bother have suggested that subjects may find LUTS more bothersome than incontinence20,30. Our data is consistent with this finding: RP subjects reported the lowest rate of post-treatment moderate to severe urinary problems, and those with pre-treatment LUTS mostly found their post-treatment incontinence less bothersome than their pre-treatment symptoms, as long as incontinence was mild.

This study has several limitations. As a non-randomized study, selection bias makes comparisons between treatment groups challenging. However, such comparisons were not a goal of this analysis, as we focused on outcome changes from pre- and post-treatment within each treatment group and aimed to identify subject characteristics that may predict a more favorable post-treatment outcome. While our results may be affected by floor/ceiling effects, we do not believe they account for the magnitude of interaction between pre-treatment LUTS and treatment group, especially for RP. Overall urinary bother is a complex entity that may not only represent a global assessment of urinary status and function, but may also encompass more abstract notions such as perceived cancer cure, coping mechanisms, and patient expectations; however, a patient’s experience and perception of their urinary status may be the ultimate measure of his urinary quality of life, an inherently subjective concept.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients’ pre-existing urinary problems heavily influence the wide spectrum of changes in urinary symptom burden seen after prostate cancer treatment. In a setting where adverse urinary consequences are common, the possibility of identifying those who may experience urinary symptom improvement should not be ignored. The impact of individualized assessment of pre-treatment urinary symptoms and its potential effect on prostate cancer treatment decision making warrants further study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding:

PROST-QA Consortium Funded by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 CA95662, RC1 CA146596, and RC1 EB011001. The Multicentric Spanish Group of Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer was supported by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III FEDER: Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (PI13/00412). Dr. Chang is supported by a Urology Care Foundation Research Scholar Award and the Martin and Diane Trust Career Development Chair in Surgery.

PROSTQA Consortium Study Group (Study Investigators, DCC and Coordinators):

The PROSTQA Consortium includes contributions in cohort design, patient accrual and follow-up from the following investigators: Meredith Regan (Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA); Larry Hembroff (Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI); John T. Wei, Dan Hamstra, Rodney Dunn, Laurel Northouse and David Wood (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI); Eric A Klein and Jay Ciezki (Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH); Jeff Michalski and Gerald Andriole (Washington University, St. Louis, MO); Mark Litwin and Chris Saigal (University of California—Los Angeles Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA); Thomas Greenfield, PhD (Eneryville, CA), Louis Pisters and Deborah Kuban (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX); Howard Sandler (Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA); Jim Hu and Adam Kibel (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA); Douglas Dahl and Anthony Zietman (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA); Peter Chang, Andrew Wagner, and Irving Kaplan (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA) and Martin G. Sanda (Emory, Atlanta, GA).

We acknowledge PROSTQA Data Coordinating Center Project Management by Jill Hardy, MS (Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI), Erin Najuch and Jonathan Chipman (Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA) and Catrina Crociani, MPH (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA), grant administration by Beth Doiron, BA (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA), and technical support from coordinators at each clinical site. We would like to thank the study participants. Without them this study would not be possible.

Multicentric Spanish Group of Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer

The following investigators are members of the Multicentric Spanish Group of Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: Monica Avila, Montse Ferrer, Olatz Garín, Yolanda Pardo, Angels Pont (IMIM - Institut Hospital del Mar d’Investigacions Mèdiques); Ana Boladeras, Ferran Ferrer, Ferran Guedea, Evelyn Martínez, Joan Pera, Montse Ventura (Institut Català d’Oncologia); Manel Castells-Esteve, José Francisco Suárez (Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge); Javier Ponce de León, Humberto Villavicencio (Fundación Puigvert); Jordi Craven-Bratle, Gemma Sancho (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau); Pablo Fernández (Instituto Oncológico de Guipúzcoa); Ismael Herruzo (Hospital Regional Carlos Haya); Helena Hernández, Víctor Muñoz (Hospital Meixoeiro- Complejo CHUVI); Asunción Hervas, Alfredo Ramos (Hospital Ramon y Cajal); Víctor Macias (Hospital Cínico Universitario de Salamaca); Josep Solé, Marta Bonet (Institut Oncologic del Valles -IOV); Alfonso Mariño (Centro Oncológico de Galicia); María José Ortiz (Hospital Virgen del Rocío); Pedro J. Prada (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias).

Attestation: Dr. Chang had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest/Disclosures:

Peter Chang: none

Meredith Regan: none

Montserrat Ferrer: none

Ferran Guedea: none

John Wei: none

Larry Hembroff: none

Jeff Michalski: none

Chris Saigal: none

Mark Litwin: none

Daniel Hamstra: none

Irving Kaplan: none

Jay Ciezki: none

Eric Klein: none

Adam Kibel consults for Dendreon and Sanofi.

Howard Sandler consults for Bayer, Medivation, Janssen, Sanofi, AstraZeneca. He is a medical advisory board member for Eviti. He has a research application pending with Myriad.

Rodney Dunn: none

Catrina Crociani: none

Martin Sanda: none

Abbreviations

- PCa

prostate cancer

- HRQOL

health related quality of life

- LUTS

lower urinary tract symptoms

- RP

radical prostatectomy

- XRT

external radiotherapy

- BT

brachytherapy

Footnotes

Work presented at the American Urological Association Annual Meeting in 5/2014 at Orlando, FL.

References

- 1.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committeee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148(5):1549–57. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sagnier PP, Girman CJ, Garraway M, Kumamoto Y, Lieber MM, Richard F, MacFarlane G, Guess HA, Jacobsen SJ, Tsukamoto T, Boyle P. International comparison of the community prevalence of symptoms of prostatism in four countries. Eur Urol. 1996;29(1):15–20. doi: 10.1159/000473711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kupelian V, Wei JT, O’Leary MP, et al. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms and effect on quality of life in a racially and ethnically diverse random sample: the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2381–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potosky AL, Davis WW, Hoffman RM, Stanford JL, Stephenson RA, Penson DF, Harlan LC. Five-year outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004 Sep 15;96(18):1358–67. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penson DF, Feng Z, Kuniyuki A, McClerran D, Albertsen PC, Deapen D, Gilliland F, Hoffman R, Stephenson RA, Potosky AL, Stanford JL. General quality of life 2 years following treatment for prostate cancer: what influences outcomes? Results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Mar 15;21(6):1147–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korfage IJ, Essink-Bot ML, Borsboom GJ, Madalinska JB, Kirkels WJ, Habbema JD, Schröder FH, de Koning HJ. Five-year follow-up of health-related quality of life after primary treatment of localized prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2005 Aug 20;116(2):291–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Downs TM, et al. Health related quality of life patterns in patients treated with interstitial prostate brachytherapy for localized prostate cancer--data from CaPSURE, prospective, multicenter. J Urol. 2003;170(5):1822–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000091426.55735.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith DP, et al. Quality of life three years after diagnosis of localised prostate cancer: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2009;339:b4817. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshimura K, Arai Y, Ichioka K, Matsui Y, Ogura K, Terai A. A 3-y prospective study of health-related and disease-specific quality of life in patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy or external beam radiotherapy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2004;7(2):144–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pardo Y, Guedea F, Aguiló F, et al. Quality-of-Life Impact of Primary Treatments for Localized Prostate Cancer in Patients Without Hormonal Treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Nov 1;28(31):4687–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen RC, Clark JA, Talcott JA. Individualizing quality-of-life outcomes reporting: how localized prostate cancer treatments affect patients with different levels of baseline urinary, bowel, and sexual function. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Aug 20;27(24):3916–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.6486. Epub 2009 Jul 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, Sandler HM, Northouse L, et al. Quality of Life and Satisfaction with Outcome among Prostate-Cancer Survivors. NEJM. 2008;358:1250–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh PC. Radical retropubic prostatectomy. In: Walsh PC, Gittes RE, Perlmutter AD, Stamey TA, editors. Campbell’s textbook of urology. 5. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1986. pp. 2754–75. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillonneau B, Vallancien G. Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: the Montsouris technique. J Urol. 2000;163:1643–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)67512-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menon M, Tewari A. Robotic radical prostatectomy and the Vattikuti Urology Institute technique: an interim analysis of results and technical points. Urology. 2003;61(Suppl 1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szymanski KM, Wei JT, Dunn RL, Sanda MG. Development and Validation of an Abbreviated Version of the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Instrument for Measuring Health-Related Quality of Life Among Prostate Cancer Survivors. Urology. 2010 Nov;76(5):1245–50. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malcowicz SB, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998 Sep 16;280(11):969–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skolarus TA, Dunn RL, Sanda MG, Chang P, Greenfield TK, Litwin MS, Wei JT PROSTQA Consortium. Minimally important difference for the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form. Urology. 2015 Jan;85(1):101–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fowler FJ, Barry MJ, Jr, Lu-Yao G, et al. Patient reported complications and follow-up treatment after radical prostatectomy. The National Medicare Experience: 1988–1990 (updated June 1993) Urology. 1993;42(6):622–9. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(93)90524-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Litwin MS, Pasta DJ, Yu J, et al. Urinary function and bother after radical prostatectomy or radiation for prostate cancer: a longitudinal, multivariate quality of life analysis from the Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor. J Urol. 2000;164:1973–1977. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)66931-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potosky AL, Legler J, Albertsen PC, et al. Health outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: results from the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(19):1582–92. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.19.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eastham JA, Kattan MW, Rogers E, Goad JR, Ohori M, Boone TB, Scardino PT. Risk Factors for urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 1996 Nov;156(5):1707–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steineck G, Helgesen F, Adolfsson J, et al. Quality of life after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:790–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Downs TM, et al. Health related quality of life patterns in patients treated with interstitial prostate brachytherapy for localized prostate cancer--data from CaPSURE, prospective, multicenter. J Urol. 2003;170(5):1822–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000091426.55735.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merrick GS, Butler WM, Wallner KE, Lief JH, Galbreath RW. Prophylactic versus therapeutic alpha-blockers after permanent prostate brachytherapy. Urology. 2002 Oct;60(4):650–5. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01840-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merrick GS, Butler WM, Wallner KE, Galbreath RW, Lief JH. Long-term urinary quality of life after permanent prostate brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003 Jun 1;56(2):454–61. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04600-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lepor H, Kaci L. The impact of open radical retropubic prostatectomy on continence and lower urinary tract symptoms: a prospective assessment using validated self-administered outcome instruments. J Urol. 2004 Mar;171(3):1216–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000113964.68020.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masters JG, Rice ML. Improvement in urinary symptoms after radical prostatectomy: a prospective evaluation of flow rates and symptom score. BJU Int. 2003;91:795–797. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slova D, Lepor H. The short-term and long-term effects of radical prostatectomy on lower urinary tract symptoms. J Urol. 2007 Dec;178(6):2397–400. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.004. discussion 2400–1. Epub 2007 Oct 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Litwin MS, Gore JL, Kwan L, et al. Quality of life after surgery, external beam irradiation, or brachytherapy for early-stage prostate cancer. Cancer. 2007;109( 11):2239– 2247. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.