Abstract

Background

The use of genetically-encoded fluorescent reporters is essential for the identification and observation of cells that express transgenic modulatory proteins. Near-infrared (NIR) fluorescent proteins have superior light penetration through biological tissue, but are not yet widely adopted.

New Method

Using the near-infrared fluorescent protein, iRFP713, improves the imaging resolution in thick tissue sections or the intact brain due to the reduced light-scattering at the longer, NIR wavelengths used to image the protein. Additionally, iRFP713 can be used to identify transgenic cells without photobleaching other fluorescent reporters or affecting opsin function. We have generated a set of adeno-associated vectors in which iRFP713 has been fused to optogenetic channels, and can be expressed constitutively or Cre-dependently.

Results

iRFP713 is detectable when expressed in neurons both in vitro and in vivo without exogenously supplied chromophore biliverdin. Neuronally-expressed iRFP713 has similar properties to GFP-like fluorescent proteins, including the ability to be translationally fused to channelrhodopsin or halorhodopsin, however, it shows superior photostability compared to EYFP. Furthermore, electrophysiological recordings from iRFP713-labeled cells compared to cells labeled with mCherry suggest that iRFP713 cells are healthier and therefore more stable and reliable in an ex vivo preparation. Lastly, we have generated a transgenic rat that expresses iRFP713 in a Cre-dependent manner.

Conclusions

Overall, we have demonstrated that iRFP713 can be used as a reporter in neurons without the use of exogenous biliverdin, with minimal impact on viability and function thereby making it feasible to extend the capabilities for imaging genetically-tagged neurons in slices and in vivo.

Keywords: iRFP713, near infrared, transgene, AAV, optogenetics

1. Introduction

Green fluorescent protein-like fluorescent proteins (GFP-like FPs) that operate in the visible spectrum have been adapted for extensive biological applications and are invaluable transgenic tools for examining cell populations, subcellular components, and second messenger signaling events such as calcium flux1,2. These reporter proteins have limited use in vivo due to restraints on light penetration through the surrounding biological tissue3. Near-infrared (NIR) light penetrates tissue better than visible light because the wavelengths in the NIR range have minimal absorption by hemoglobin and are less scattered by water and lipid-containing cell structures4,5, thus enabling the excitation and detection of signals at greater depths. Fluorescent reporter proteins with excitation/emission spectra in the NIR range can therefore be preferable to visible spectrum reporters for in vivo and ex vivo imaging applications6.

The first reported near-infrared fluorescent protein used for in vivo imaging, IFP1.47, was derived from Deinococcus radiodurans and required exogenously supplied biliverdin (its chromophore, BV) or heme oxidase (HO1), the enzyme that produces BV from the metabolic breakdown of heme8, in order to produce detectable fluorescence in E. coli or mammalian cell culture. Although the initial in vivo experiments with IFP1.4 and its descendant IFP2.09 were successful, other studies have shown that the overexpression of HO1 in neurons reduces their sensitivity to oxidative stress10 and causes changes in ERK signaling pathways11. These factors have likely prevented the widespread adoption of these reporters in neuroscience.

In 2011, Filonov et al. described the construction and characterization of iRFP713 (originally called iRFP) derived from Rhodopseudomonas palustris12. This protein also required BV, but exhibited robust fluorescence in transfected HeLa cells without the exogenous supply of BV or the overexpression of HO112. Virally-transduced iRFP713-expressing mouse liver and spleen, as well as transplanted xenografts, can be tracked in vivo by whole animal imaging3,12–14. When iRFP713 is expressed under a CAG promoter in transgenic mice, homogenous expression was observed throughout the body, including the anatomical brain, but specific observation of neurons was not discussed15. The repertoire of iRFP713-derived tools has since expanded to include monomeric versions with organelle-localization tags, blue- and red-shifted variants for two-channel imaging16,17, and conditional variants that exhibit protein-association dependent fluorescence16.

The use of an iRFP-based reporter in neurons has been described with mouse and rat models16,18,19. While these studies have shown that iRFPs are fluorescent in this cell type without exogenous BV, little has been done to characterize the side-effects that may arise from its ectopic expression, in terms of cytotoxicity or changes in cell signaling. Specifically, the detectability of iRFP713 fluorescence within different compartments of different neuronal subtypes, as well as its cytotoxicity, photostability, and functional impact when fused to optogenetic proteins. These effects must be evaluated both in vitro and in vivo.

Cellular functions are compartmentalized into organelles, and fluorescent reporter proteins can be trafficked into specific organelles by fusing them to endogenous proteins (or their domains) that normally traffic to such organelles. This capability has been a critical feature for identifying changes in the morphology, distribution and overall size of various organelles. In addition, organelle-specific expression is a common method for demonstrating overlapping expression of proteins or processes of interest in each cell by using different reporters. By visually identifying the boundaries of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or mitochondria, researchers have shown mechanistic and correlative relationships between changes in organelle size and distribution that relate to energetic and metabolic changes in the cell20. Although some fluorescent proteins have a natural affinity for specific cellular compartments, they can also be directed by conjugation with known localization domains.

In addition to being compatible with these localization domains, iRFPs have the additional requirement of accessing BV within the destination compartment, or the capability to bind and retain BV while en route. Shcherbakova et al. have tagged iRFP713 and its variants with many of these various domains and shown they function as expected in HeLa cells16,17. Whether this holds true in the context of neurons has yet to be determined.

Fluorescent proteins are commonly used in species that did not evolve with comparable proteins. Cells expressing foreign genes are not always healthy and viable, particularly when used in vivo. This issue becomes relevant when the reporter protein is present in high concentrations or produces a cytotoxic metabolite21. Expression of iRFP713 or its variants in HeLa and MTLn3 cell lines did not produce any notable disadvantage to survival over many generations12,17, however defining the cytotoxicity profile of this protein in neurons is a critical component to successfully implementing it as a reporter for optogenetic or electrophysiological experiments.

Another key element of modern reporter proteins is its resistance to photobleaching (photostability) caused by photon-induced inactivation of the fluorophore. Photostability can be extended with the limited use of light sources for excitation, but there are constraints placed on long term or repetitive imaging that are defined by the choice of fluorescent reporter. Decades of engineering and discovery efforts have extended photostability of GFP-like fluorescent reporters and led to catalogues of robust fluorophores. When expressed in HeLa cells, the one-photon photostability (t1/2) of iRFP713 was at least 15 minutes12,16,17, but this has not yet been addressed in neurons. Optogenetic approaches for manipulating neuronal circuits typically use opsins whose ion transport function is activated by light in the visible spectrum (450 – 650 nm), with bioengineering efforts underway to shift into longer wavelengths22. Visualization of cells expressing an opsin is possible by fusing a fluorescent protein that can be detected within the same, or different, wavelength range as used for opsin activation. Ideally, iRFPs would enable a translational fusion that could be detected in the near infrared (>650 nm) without activating or altering the function of the fused opsin.

To demonstrate that neuronally-expressed iRFP713 has a performance that is preferable to that of visible spectrum fluorescent proteins, we report the results of a wide range of detailed comparisons between iRFP713 and GFP-like FPs in cell culture, virally-transduced rodents and transgenic rats. We also describe the development of a transgenic rat that expresses iRFP713 in a Cre-dependent manner.

2. Methods

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for animal research and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the IACUC at the Janelia Research Campus, Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

2.1 Vector and BAC Construction

All plasmids produced in this study were constructed using ligation-independent cloning. The iRFP plasmid (Addgene #31857) was used as a template for PCR with linkered oligos, and the resulting amplicon was recombined with various linearized plasmid backbones using In-Fusion cloning mix (Clontech 638909). The AAV packaging plasmid backbones pAAV-EF1a-double floxed-hChR2(H134R)-mCherry-WPRE-hGHpA (Addgene #20297), pAAV-CaMKIIa-hChR2(H134R)-EYFP (Addgene #26969), pAAV-CaMKIIa-eNpHR 3.0-EYFP (Addgene #26971), and pAAV-CaMKII-EYFP were generously provided by Dr. Karl Deisseroth (Stanford University). The murine c-fos promoter was adapted for use with AAV by amplifying the first 1.7 kb from the c-fos-GFP and using it to replace the CaMKII promoter in pAAV-CaMKII-EYFP. The c-fos-GFP plasmid was generously provided by Alison Barth23. A double-stranded AAV backbone using the CMV promoter was used to express IFP1.4 (pOTTC169) and iRFP713 (pOTTC342) in the initial experiments comparing baseline fluorescence. iRFP713 was also used to replace the original fluorescent proteins in the Clontech Living Colors expression vectors as translational fusions with the respective targeting domains for localization to the endoplasmic reticulum (Addgene #59136), cell membrane (Addgene #59134) and mitochondria (Addgene #59135). For nuclear localization, iRFP713 was appended with a nuclear localization signal, and driven by the c-fos promotor (Addgene #59132). An equivalent vector was created for EYFP (Addgene #59133). iRFP713 and EYFP were also put under the c-fos promoter without a nuclear trafficking element (Addgene #47906 and #47907, respectively). In optogenetic studies, iRFP713 was put under a CaMKIIa promotor (Addgene #47903) and conjugated to halorhodopsin (Addgene #47904) and channelrhodopsin (Addgene #47905). Cre-dependent constructs driven by the EF1a promoter were also created for mCherry (Addgene #47636), EYFP (Addgene #27056), iRFP713 (Addgene #47626), iRFP713 conjugated to halorhodopsin (Addgene #47631) and iRFP713 conjugated to channelrhodopsin (Addgene #47633). Additional information on the DNA constructs used in this study can be found in Supplementary Figure 1.

2.2 AAV packaging and purification

All AAV vectors were packaged as serotype 1 using triple transfection method as previously described24. AAV vectors were purified using affinity chromatography and titered by qPCR as described previously25.

2.3 Promoter-dependent expression

SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were maintained as previously described26. For primary cortical neurons, cells were prepared as previously described24. Cells were plated at 6×104 cells/well in 96 well polyethyleneimine(PEI)-coated plates. Half-medium exchanges were performed on days 4, 6, 8, 11, and 13. Viral transductions were performed on day 6. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) at 1 μM for 24 hours was used to induce c-fos expression.

2.4 Subcellular Localization of iRFP713

To verify that iRFP713 could be localized and detected to subcellular compartments, the trafficking signals commercially available for GFP-like FPs were conjugated to iRFP713. The iRFP713 versions were directly compared to the commercial products targeting four organelles: Nucleus27,28 (Clontech 632408); Endoplasmic reticulum lumen29 (Clontech 632409); Inner plasma membrane surface30 (Clontech 632511); Mitochondria31 (Clontech 632421). The iRFP713 plasmids were electroporated along with the corresponding commercial vectors into rat primary neurons prepared from E15–E16 Sprague-Dawley rat embryos24 to evaluate similarity of expression profiles. Briefly, 12 mm round glass coverslips were coated with PEI solution on the day before seeding cells. The coating solution was prepared by diluting a 50% (w/v) solution of PEI 1:500 in 150 mM borate buffer (pH 8.5). Coating solution was added to coverslips for 6h, washed 3 times with deionized water, and allowed to dry overnight. Rat primary cortical neurons were isolated and cultured under conditions described above. For DNA transfections, 9.0×105 cells were transfected with 2 μg of DNA (1.2 μg of the tagged iRFP plasmid and 0.8 μg for the corresponding commercial plasmid) using the Neon Transfection System (Invitrogen). Following electroporation, cells were plated to 24-well plates containing PEI-coated 12 mm glass coverslips. Cells were fixed with fresh 4% PFA (prepared in 1x PBS, pH 7.4) 15 days after plating. Coverslips were mounted to glass slides with MOWIOL, and imaged using an Olympus Fluoview FV100 BX61WI upright confocal laser scanning microscope using Olympus Fluoview 3.1 software with lasers: LD405/440nm (Laser Diode) for DAPI, Ar488nm (Argon) for GFP/YFP, LD559nm for DsRed, and LD635nm for iRFP713. Images were prepared for figures using NIH ImageJ.

2.5 Photostability, cytotoxicity and phototoxicity assay

Primary rat cortical neurons in 96 well plates were transduced with AAV vectors expressing iRFP713 or EYFP (4.4×1012 viral genomes (vg)/mL and 4.2×1012 vg/mL, respectively) on DIV6 by removing 100 μL of media from wells and adding 5 μL of virus for 2 hrs. Feeding protocol of 50% media exchange was repeated on DIV8 and DIV11. On DIV13 cells were fed and subjected to fluorescent light. Using a 40x magnification, cells transduced with AAV1-CamKIIa-EYFP were continuously exposed to FITC filtered light for 30 min at an intensity of 5.1mW (n=3). Similarly, cells transduced with AAV1-CaMKII-iRFP were exposed to CY5.5 filtered light with a light intensity of 12.5 mW for 30min (n=3). After light exposure, the cells were placed back into the incubator overnight. On DIV14, under sterile conditions, 100 μL of media was removed and 15 μL of CellTiter Aqueous One Solution Reagent (Promega) was added to each well to assess viability. Cells were placed back into the 37°C incubator for 1 hr. Using a plate reader, absorbance was read at 490nm.

2.6 In vivo two photon imaging

Mice (C57BL/6Crl, Charles River) were anaesthetized with isoflurane (1–2% by volume in O2). A small craniotomy was opened above the mouse primary visual cortex (V1) and 30 nL of AAV1-CaMKII-iRFP (4.4×1012 vg/mL) was injected into V1 (left hemisphere, 3.4 mm posterior to Bregma; 2.7 mm lateral from midline; 0.4 mm below pia) using a glass pipette with a 15–20 μm opening. A cranial window made of a single 170 μm-thick coverslip (Fisher Scientific no. 1) was installed, followed by the attachment of a titanium headpost to the skull with cyanoacrylate glue and dental acrylic. 3–4 weeks after surgery, in vivo two-photon images of iRFP713-expressing neurons were collected with a two-photon fluorescence microscope as described previously18, at pixel sizes of 0.25–1 μm and frame rates of 1–2 Hz. 920nm output of a femtosecond laser (Coherent, Chameleon Ultra II) was found to effectively excite iRFP713 two-photon fluorescence at post-objective powers of 8–30 mW (50–200 μm depth), 60 mW (300–400 μm depth), 100 mW (450–500 μm depth) and 130 mW (550 μm depth). A photomultiplier tube (Hamamatsu, H7422-40) was used to detect the fluorescence.

2.7 Transgenic rat lines

The individual animal founders of the transgene were outcrossed to wildtype rats of the same background, and used to found the following lines: LE-Tg(DIO-iRFP)3Ottc (RGD ID 9588559, RRRC #747, Long Evans), SD-Tg(DIO-iRFP)9Ottc (RGD ID 9588562, RRRC #748, Sprague Dawley) and LE-Tg(DAT::iCre)1Ottc (RGD 9588572, RRRC#730, Long Evans). These animals are available from the Rat Resource and Research Center (RRRC), although the LE-Tg(DAT::iCre) line has been replaced by RRRC758 since this data was collected. Description of the production of these lines is included in the supplemental methods section.

2.8 Cre-dependent expression of AAV-iRFP in vivo

Ten-week old male Long Evans DAT-iCre L1 transgenic rats received a unilateral injection of AAV-EF1a-DIO-iRFP in the substantia nigra region of the midbrain. Each rat was anesthetized with 80 mg/kg of ketamine and 8 mg/kg of xylazine following isoflurane administration before being placed in the stereotaxic apparatus. A total of 1 μL of virus (4.4×1012 vg/mL) was injected at a rate of 0.25 μL/min using a Nanofil 10 μL syringe and 33 G blunt needle (World Precision Instruments). The needle was left in place for two minutes after each injection to allow for dripping. Coordinates, measured from bregma, used were AP = −5.8 mm, ML = 1.9 mm, and DV = −7.3. Seven weeks following injections, rats were transcardially perfused using 0.9% saline followed by 4% PFA. Brains were subjected to a three-day sucrose gradient of 18% followed by 30% sucrose before being flash frozen on dry ice. 30 μm coronal sections were obtained with a cryostat. Perfused sections were visualized with epifluorescence, laser confocal microscopy or Li-Cor. For immunohistochemistry, sections were blocked for approximately one hour in 4% goat serum, 0.3% Triton-X in 0.1M phosphate buffered saline before overnight, 4°C incubation in primary antibody. Coronal sections were immunostained with anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (rabbit, Millipore, AB152 at 1:1000) primary antibody and Alexa-Fluor 568 (Goat anti-rabbit, Invitrogen #A11004 at 1:500) secondary antibody.

2.9 Electrophysiological studies

DAT-iCre Long Evans transgenic rats (LE-Tg(DAT-iCre)6Ottc) of both sexes (8–16 weeks of age) were used for brain slice electrophysiology experiments. Injections were performed as described above. The viral injections DIO-EYFP (Addgene #27056, 1.9×1012 vg/mL or 2.3×1012 vg/mL) or DIO-iRFP (Addgene #47626, 4.4×1012 vg/mL), as well as the DIO-ChR2-iRFP (Addgene #47633, 1.4×1012 vg/mL), DIO-ChR2-EYFP (Addgene #20298, 6.3×1012 vg/mL or 1.9×1012 vg/mL), DIO-eNpHR3.0-iRFP (Addgene #47631, 8.5×1011 vg/mL) and DIO-eNpHR3.0-EYFP (Addgene #26966, 4.3×1011 vg/mL). For each, undiluted virus was injected unilaterally in the substantia nigra, using the coordinates AP = −5.8 mm, ML = ±1.9 mm, and DV = −7.3 mm, measured from bregma. In addition, DIO-mCherry (Addgene #47636, 1.0×1012 vg/mL) injections utilized the stereotaxic coordinates AP: −6.0 mm, ML = ±1.9 mm, DV = −7.1 mm)

Brain slice electrophysiology experiments were performed 2–4 weeks after viral injection into the midbrain. Animals were first deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and then transcardially perfused with an ice-cold solution containing (in mM) 93 NMDG, 93 HCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 30 NaHCO3, 20 HEPES, 25 Glucose, 5 Na-ascorbate, 2 Thiourea, 3 Na-pyruvate, 10 MgSO4, 0.5 CaCl2. Brains were rapidly removed, and horizontal midbrain slices (200–220 μm) were made using a vibratome (Leica VT-1000S). Slices were then incubated in a holding solution containing (mM) 92 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 30 NaHCO3, 20 HEPES, 25 Glucose, 5 Na-ascorbate, 2 Thiourea, 3 Na-pyruvate, 2 MgSO4, 0.5 CaCl2 (32–34°C) for 15–30 minutes. Following this, the holding chamber was kept at room temperature for the duration of the experiment. Slices were then transferred to a recording chamber and superfused (2–3 mL/min) with artificial cerebrospinal fluid containing 126 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 2.4 CaCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 21.4 NaHCO3, 11.1 glucose maintained at 32–34°C. All solutions were continually oxygenated (95% oxygen, 5% carbon dioxide). Glass pipettes (tip resistance 2–4 MΩ) were used for whole cell recordings and were filled with an intracellular solution containing (mM) 115 K-gluconate, 20 KCl, 1.5 MgCl2, .025 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 Mg-ATP, 0.2 Na-GTP, 10 Na2-phosphocreatine (pH 7.2–7.3, ~290 mOsm/kg).

Cells were identified using an upright microscope with differential interference optics (Olympus BX61WI) equipped with a scanning confocal system (Olympus Fluoview F1000). Confocal imaging of midbrain dopamine neurons expressing mCherry, EYFP or iRFP713 was conducted with 515 nm or 635 nm laser light. Images were acquired using Olympus Fluoview software (version 3.0).

Electrophysiology data were acquired using an Axopatch 200B amplifier in either voltage clamp or current clamp mode. Data were filtered at 5 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz using a National Instruments USB-6221 digitizer. Win WCP software (University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK) was used to collect electrophysiological data. Firing recordings were performed in cell-attached configuration. All whole cell voltage clamp recordings were performed using a holding potential of −60 mV. Holding currents reported represent the amount of current injected to maintain the cell at −60 mV. Input resistance was calculated using −10 mV steps during voltage clamp recordings. Ih amplitude was measured by taking the difference between peak and steady state current values following a −50 mV step under voltage clamp. For optogenetic experiments, a 473 nm laser was used (150 mW). The optic fiber was placed near the recorded cell, and all experiments were conducted using a light intensity of 5–10 mW.

Data are expressed as mean +/− SEM. Prism software was used for data analysis (Graphpad software, San Diego, CA). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. A one-way ANOVA was used for analysis of mCherry, EYFP and iRFP713 data. A Student’s T-test was used to compare groups in optogenetic experiments.

2.10 Characterization of DIO-iRFP transgenic rats

For evaluating the DIO-iRFP transgenic rats, six to twelve weeks old male and female “LE-Tg(DIO-iRFP)3Ottc” and “SD Tg(DIO-iRFP)9Ottc” rats of approximately 5–6 months of age (300–600 grams) received unilateral injections of AAV1-GFP-Cre (6.0×1010 vg/mL) in the pre-frontal cortex (PFC; AP = 2.5 mm, ML = 0.9 mm, and DV = −3.5 mm), striatum (STR; AP = 0.0, ML = −3.0 mm, DV = −6.5 to −5.5 mm, and midbrain (MB; AP = −5.8 mm, ML = 1.9 mm, DV = −7.3 mm). The volumes were either 1 μL (PFC, MB), or 2 μL (STR). The ssAAV1-GFP-Cre plasmid expresses a GFP-Cre recombinase fusion protein from a CMV promoter. Each rat was anesthetized with 80 mg/kg of Ketamine and 8 mg/kg of Xylazine following isoflurane administration before being placed in the stereotaxic apparatus. Two to three weeks post-surgery (unless noted otherwise), rats were transcardially perfused and brains prepared as described above (Section 2.8). Thirty micron cryosections were obtained and immunostained for tyrosine hydroxylase (rabbit, Millipore, AB152 at 1:1000) or NeuN (mouse anti-NeuN Millipore AB377 at 1:500) at 4°C. The next day, sections were incubated for one hour at room temperature with secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488, Invitrogen #A11034 at 1:500 for anti-TH staining, or AlexaFlour568 Invitrogen #A11004 at 1:500 for anti-NeuN staining). Stained sections were imaged with epifluorescence and laser confocal microscopy.

DAT::iCre and DIO-iRFP double positive rats, produced by crossing two transgenic lines LE-Tg(DIO-iRFP)3Ottc and LE-Tg(DAT::iCre)1Ottc, were perfused at 12 weeks of age and their brains prepared as described above (Section 2.8). Midbrain sections were directly mounted to gelatin-coated slides and scanned at 700 nm excitation with Li-Cor Odyssey near-infrared (NIR) scanner. Another set of midbrain sections were immunostained with antibodies to tyrosine hydroxylase (TH;1:1000, cat# AB152 EMD Millipore) and Cre recombinase (1:1000, cat#MAB3120, EMD Millipore). The secondary antibodies were goat-anti rabbit-Alexa Fluor 488 (Life Technologies) for TH, goat-anti-mouse-Alexa Fluor 568 for Cre protein. Stained sections were observed and photographed with laser confocal microscopy. iRFP713-positive dopaminergic neurons were counted in three sections for each of three rats.

3. Results

iRFP713 has features and characteristics that are comparable to GFP-like FPs when expressed in neurons.

3.1 iRFP713 expression

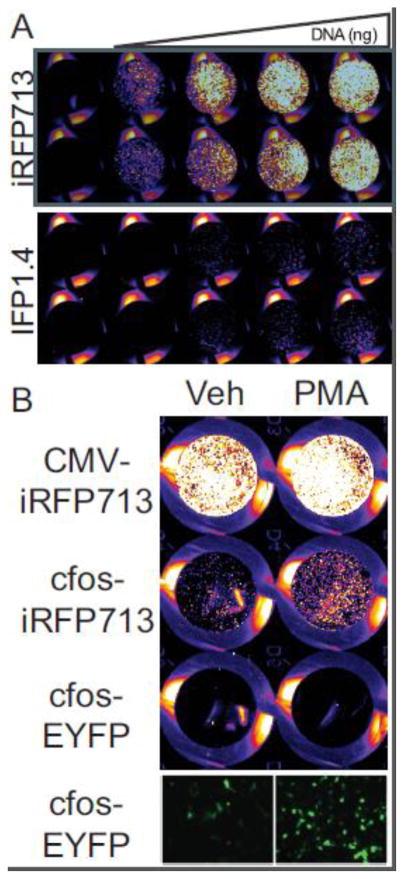

Under normal growth conditions, iRFP713 expression was detectable in SH-SY5Y cells, an immortalized human neuroblastoma cell line, and the fluorescence intensity increased in a dose-dependent manner with the amount of transfected plasmid, whereas IFP1.4 fluorescence remained near the lower limit of detection even at the highest dose of plasmid tested (Figure 1A). In addition, iRFP expression driven by the c-Fos promoter, a neuronal activity-dependent promoter, is inducible by PMA in SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Ectopically expressed iRFP713 does not require exogenously-supplied BV for fluorescence.

A) Increasing amounts of plasmid DNA encoding iRFP713 (top) or IFP1.4 (bottom) were transfected into SH-SY5Y cells and imaged 48 hours later using the 700nm excitation channel of a Li-Cor Odyssey near-infrared scanner. B) SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with plasmids expressing fluorescent proteins driven by the c-fos promoter or the CMV promoter, and then treated with 1 μM PMA for 24 hours. Fluorescence was measured by Li-Cor Odyssey scanning (top three rows) or epifluorescence using “GFP filter set” (bottom row). The observed increase in infrared fluorescence is specific to the c-fos-iRFP construct.

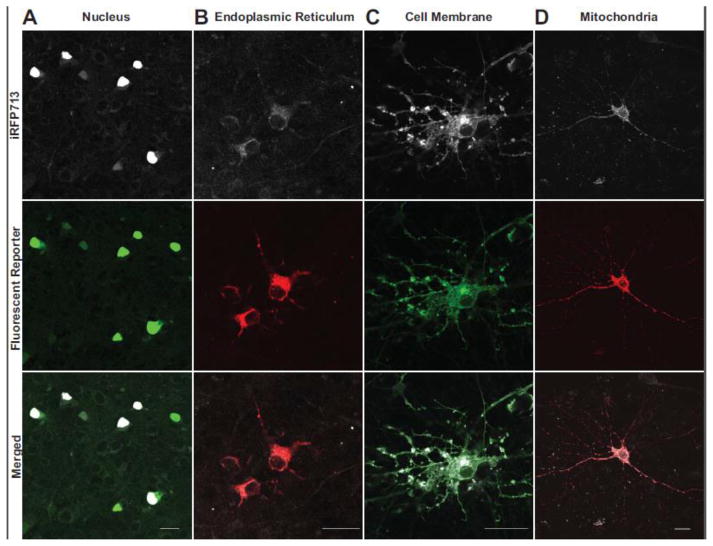

3.2 Subcellular trafficking of iRFP713

Rat primary cortical neuron cultures co-transfected with EYFP and iRFP713 conjugated to nuclear-localization domains (the NLS from SV40 large T antigen) showed patterns consistent with nuclear trafficking (Figure 2A). Co-transfection of DsRed and iRFP713 plasmids conjugated to endoplasmic reticulum trafficking domains (a N-terminal signal peptide and C-termal KDEL tag) resulted in fluorescence patterns consistent with the ER lumen (Figure 2B). Co-transfection of DsRed and iRFP713 each conjugated to trafficking domains for the inner membrane surface (palmitylation signal) resulted in fluorescence patterns consistent with the cell membrane (Figure 2C). Co-transfection of DsRed and iRFP713 conjugated to a mitochondrial trafficking signal (MARKCK) resulted in fluorescent patterns consistent with mitochondria (Figure 2D). Similar results were observed in SH-SY5Y cells (Supplemental Figure 2) and have already been shown with color-shifted iRFP variants in HeLa cells17. These findings indicate that rat primary neurons produce enough bioavailable BV to allow iRFP713 fluorescence and are similar to those previously reported for rat hippocampal cells expressing monomeric variants derived from iRFP71316.

Figure 2. Subcellular targeting of iRFP713 reporters in rat primary cortical neurons.

Protein trafficking signals were appended to iRFP to target its localization to the (A) nucleus, (B) endoplasmic reticulum, (C) plasma membrane, or (D) mitochondria of rat primary cortical neurons. Similarly-targeted EYFP, DsRed, or AcGFP proteins were co-expressed to compare localization patterns of fluorescent proteins with the corresponding trafficking signals. Scale bar represents 20 microns.

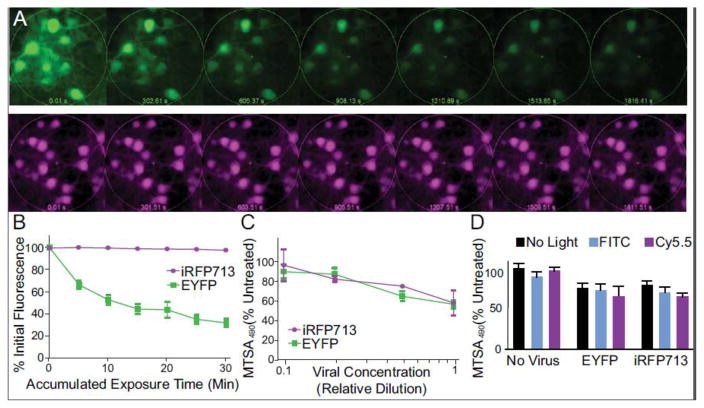

3.3 Photostability, cytotoxicity, and phototoxicity in neurons

After 5 minutes of exposure to a constant light source through a FITC filter, EYFP exhibited a 33% decrease in fluorescence whereas iRFP713 retained 99% of its fluorescence after 30 minutes of continuous illumination through a Cy5.5 filter (Figure 3A and B). As expected, no significant reduction in fluorescence was observed when each fluorescent protein was exposed to the converse filter for 30 minutes (data not shown). Although we observed some evidence of cytotoxicity that was dependent on viral dose in primary neurons transduced with either AAV1-CaMKII-EYFP or AAV1-CaMKII-iRFP, there was no difference in the effect that could be attributed to either transgene (Figure 3C). This indicates that ectopic expression of iRFP713 is not more toxic than EYFP in cultured rat neurons, and agrees with previous reports17. No signs of acute phototoxicity (light-dependent cytotoxicity) were observed with either transgene after similarly transduced cells were exposed to 30 minutes of constant illumination with either the FITC or Cy5.5 filters (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Photostability and toxicity of iRFP713 compared to EYFP.

A) Time lapse montage of primary neurons transduced with AAV-CaMKII-EYFP and imaged continuously for 30 minutes with a FITC filter (top row). A similar montage of cells transduced with AAV-CaMKII-iRFP and imaged with a Cy5.5 filter set for 30 minutes (bottom row). B) Densitometry of the fluorescent signals at 5 minute intervals during continuous exposure (n=3). (C) Cell viability was measured using MTS assay at various concentrations of virus. (D) Exposure to 30 minutes of constant light (either Cy5.5 or FITC filtered) did not significantly alter cell viability as measured by MTS assay.

3.4 In-vivo expression of iRFP713 in rodent brain

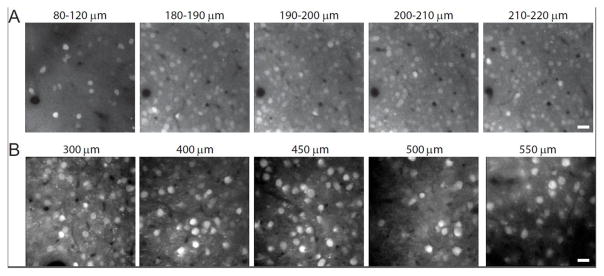

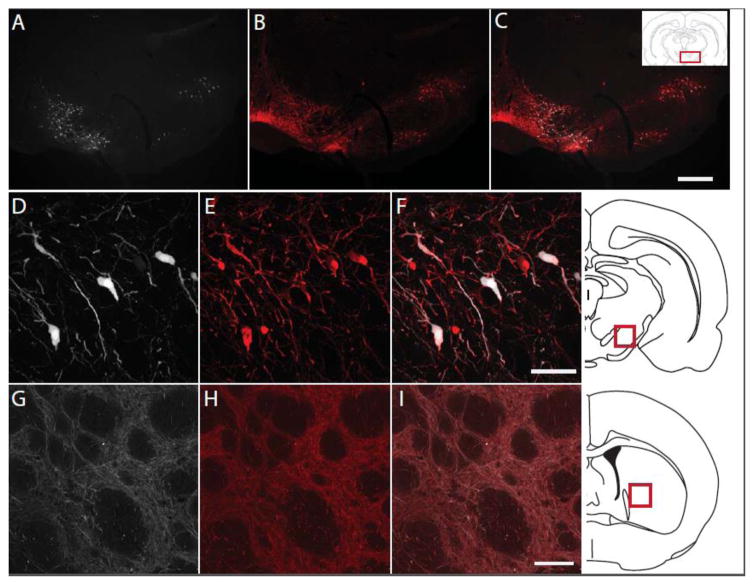

Four weeks after intracranial injection of an AAV vector encoding iRFP713, a fluorescent signal was detected in mouse cortical neurons using two-photon microscopy (Figure 4A,B). iRFP713 expression could also be detected in midbrain dopaminergic neurons of DAT-Cre transgenic rats seven weeks after midbrain injection of Cre-dependent AAV vector expressing iRFP713 (Figure 5A–C). Tyrosine hydroxylase-positive cells expressed iRFP713 in the soma of cells in the midbrain (Figure 5D–F) and filled their processes that project to the striatum (Figure 5G–I).

Figure 4. In vivo two-photon imaging of iRFP713-expressing neurons in mouse cortex.

(A) in vivo two-photon fluorescence images of neurons in supragranular layer 1 and layer 2/3. (B) in vivo two-photon fluorescence images of neurons in granular layer 4 and infragranular layer 5. Scale bars are 20 μm.

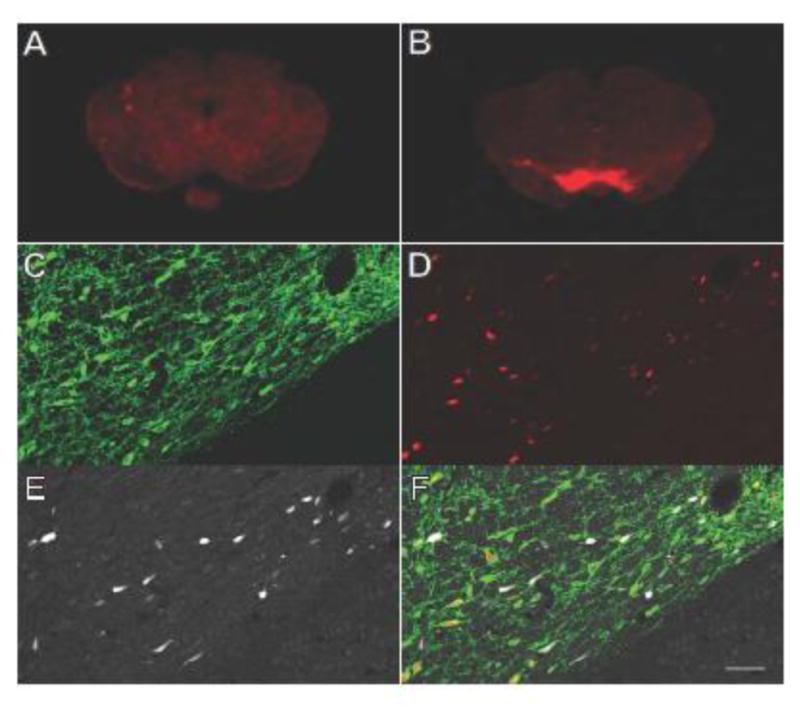

Figure 5. Cre-dependent iRFP713 selectively transduces dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal pathway of a DAT-iCre rat.

AAV-DIO-iRFP was injected into the midbrain of a DAT-Cre transgenic rat. After 7 weeks, coronal sections of the midbrain (A–F) and striatum (G–I) were immunostained for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH). The iRFP713 signal (white) colocalizes with TH immunoreactivity (red) in cell bodies of the midbrain shown at low magnification (A–C) and high magnification (D–F). The iRFP713 signal is also present in TH-immunoreactive fibers of the striatum (G–I). Representative images of striatal and midbrain brain locations are shown for reference. Scale bars are 250 μm (C) and 50 μm (F and I).

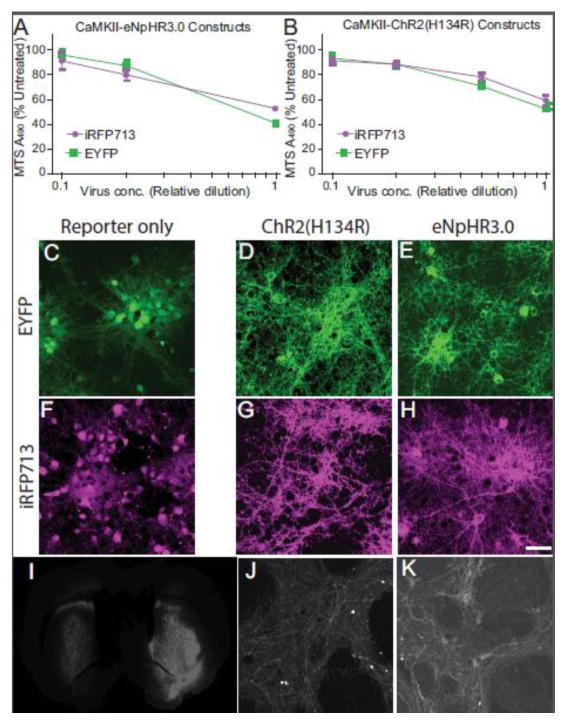

3.5 Functional compatibility of iRFP713 fusion with opsins used for optogenetics

Given that iRFP713 fluorescence was detectable in neurons in vivo, we created AAV vectors that expressed channelrhodopsin (ChR2(H134R)) or halorhodopsin (eNpHR3.0) translationally fused to iRFP713. These two prominently used optogenetic proteins are commonly fused EYFP. Therefore, we first compared the toxicity of EYFP to iRFP713 as fusion proteins. Rat primary neurons were transduced with AAV vectors containing a CaMKII promoter driving the expression of the FP fused to ChR2 (H134R) or fused to eNpHR3.0. As seen with overexpression of each of the fusion proteins alone (Figure 3C), all vectors caused a dose-dependent decrease in viability that was independent of the protein being expressed (Figure 6A–B). When used to transduce primary neurons, AAV expressing iRFP713 alone, iRFP713 fused to ChR2(H134R) or fused to eNpHR3.0 exhibited similar localization patterns compared to the analogous EYFP expressing vectors (Figure 6 C–H). The opsin- fused iRFPs produced a fluorescent signal consistent with membrane localization. This expression pattern differed from unmodified iRFP713, which appeared to be distributed throughout the cytoplasm. Intra-striatal injection of AAV expressing ChR2(H134R)-iRFP or eNpHR3.0-iRFP resulted in detectable fluorescence by an NIR scanner and microscopy with Cy5.5 filter (Figure 6 I–K). The cellular distribution pattern of the iRFP713 fluorescence appeared to extend into the processes of neurons of the striatum (Figure 6 J–K).

Figure 6. Toxicity of iRFP713 conjugates compared to EYFP.

The viability of rat primary cortical cultures transduced with iRFP713 compared to those transduced with EYFP was compared for (A) the fusion to eNpHR3.0 or (B) the fusion to ChR2(H134R). There was a significant negative effect of viral dose but not the particular fluorescent protein (2-way ANOVA) for all vectors tested. C) “Untagged” EYFP exhibits a cytosolic and nuclear pattern of expression. D) When fused to channelrhodopsin (ChR2(H134R)-EYFP), the EYFP signal is present in the processes of neurons. E) Fusion to halorhodopsin (eNpHR3.0-EYFP) results in a distribution pattern like that of ChR2-fusions, but with appearance of perinuclear protein aggregates. The distinct patterns of fluorescent signal are reproduced after EYFP was replaced with iRFP713: “untagged iRFP” (F), ChR2(H134R)-iRFP (G), and eNpHR3.0-iRFP (H, Scale bar is 50 μm). For in vivo testing, AAV vectors expressing ChR2(H134R)-iRFP (I, left side and J) and eNpHR3.0-iRFP (I, right side and K) were injected in the striatum and brains imaged 3 weeks later with an Odyssey NIR scanner (Li-Cor; I) and microscopy (J, K).

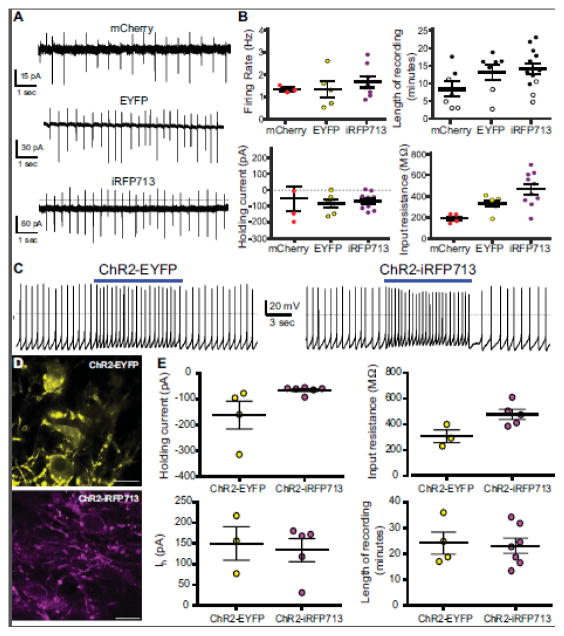

3.6 Electrophysiological characterization of dopamine neurons expressing iRFP713 and ChR2(H134R)-iRFP fusion protein

We demonstrated that iRFP713 can be specifically targeted to dopaminergic neurons (Figure 5), but whether neurons expressing iRFP713 maintain their functionality is a critical question in determining the usefulness of using iRFP713 with ex vivo brain slice preparations. Thus, ex vivo brain slice electrophysiology was used to measure electrical properties of dopamine neurons. Dopamine neurons expressing mCherry and EYFP were used for purposes of comparison as these FPs are frequently used to label cells for in vitro electrophysiology experiments. Dopamine neurons alternate between two firing modes in vivo: intrinsically driven tonic, pacemaker firing (0.5–5 Hz) and phasic burst firing (10–20 Hz) that is initiated by activation of glutamatergic inputs. Dopamine neurons typically maintain tonic firing in the in vitro slice preparation, thus we measured firing frequency in cells that maintained firing activity in each group. Example firing traces are shown in Figure 7A. We found 38% of mCherry+ cells recorded were tonically firing at the time of patching whereas 67% of recorded iRFP713 + cells and 72% of recorded EYFP cells were firing at the time of patching. We measured the firing rate of all cells that maintained tonic firing during our recordings, and found no difference in firing frequency between mCherry+, EYFP+ or iRFP713+ neurons (one-way ANOVA, n=3–8 cells/group, F=0.43, df=2, p=0.66) (Figure 7B, upper left panel). Using whole-cell voltage clamp, we measured basic cellular properties of dopamine neurons expressing various FPs. While there was no significant difference in holding current between any group, variability was much greater in the mCherry+ cells, whereas EYFP+ cells and iRFP713+ cells required a similar amount of current to maintain a holding potential of −60 mV, and the data were distributed similarly (one-way ANOVA, n=4–11 cells/group, F=0.21, df=2, p=0.81) (Figure 7B, bottom left panel). There was a significant effect of FP type on input resistance (one-way ANOVA, n=4–10 cells/group, F=7.69, df=2, p=0.004) primarily driven by a difference between mCherry+ and iRFP713+ cells (Bonferroni post-test, p < 0.005) (Figure 7B, bottom right panel). Input resistance provides a measurement of membrane integrity and excitability. While there was no difference in the overall length of recording (n=7–12 cells/group, F=2.37, df=2, p=0.12), only 43% of mCherry+ cells remained stable and healthy enough to provide a complete dataset, while complete data sets were obtained from 71% of EYFP+ cells and 75% of iRFP713+ cells (Figure 7B, upper right panel).

Figure 7. Electrophysiological characterization of dopamine neurons expressing fluorescent proteins.

A) Example traces from cell-attached recordings performed in tonically firing dopamine neurons. B) Summary graphs for all dopamine neurons recorded. Length of recording data includes cells for which a complete data set was collected prior to terminating the experiment (filled) and cells that provided some data but died or became unstable prior to collecting a full data set (empty). Holding current represents the amount of current that is required to maintain the cell at a holding potential of −60 mV. Input resistance measures membrane integrity and electrical leakiness. C) Example traces from cells expressing ChR2-EYFP and ChR2-iRFP713. Exposure to blue light-induced the expected increases in firing frequency. Blue line indicates the presence of 473 nm light. D) Confocal images of dopamine neurons expression ChR2-EYFP (top) and ChR2-iRFP713 (bottom). Scale bars = 30 um. E) Summary graphs as described above for all recorded dopamine neurons expression ChR2-EYFP or ChR2-iRFP713.

To determine if ChR2 remains functional when translationally fused with iRFP713, whole cell recordings were performed in ChR2-EYFP+ or ChR2-iRFP713+ dopamine neurons. Both ChR2-EYFP+ and ChR2-iRFP713+ cells consistently showed light-activated responses. ChR2-EYFP+ and ChR2-iRFP+ cells increased their frequency of firing when exposed to blue light stimulation, as shown in Figure 7C. Confocal images of the expression pattern of ChR2-EYFP and ChR2-iRFP713 in dopamine neurons are also shown (Figure 7D). There are no significant differences in holding current (Unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, n=4–6 cells/group, t=1.78, df=3, p=0.17), H-current (Unpaired t-test, n=3–5 cells/group, t=0.34, df=6, p=0.74), or length of recording between ChR2-EYFP+ and ChR2-iRFP713+ cells (Unpaired t-test, n=4–7 cells/group, t=0.2, df=9, p=0.84). However, input resistance was significantly higher in ChR2-iRFP713+ cells (Unpaired t-test, n=3–5 cells/group, t=2.66, df=6, p=0.04) (Figure 7E). Taken together, these data suggest that iRFP713 does not negatively impact the health or integrity of dopamine neurons. Additionally, iRFP713 can be translationally fused with optogenetic constructs such as channelrhodopsin without any loss of functionality.

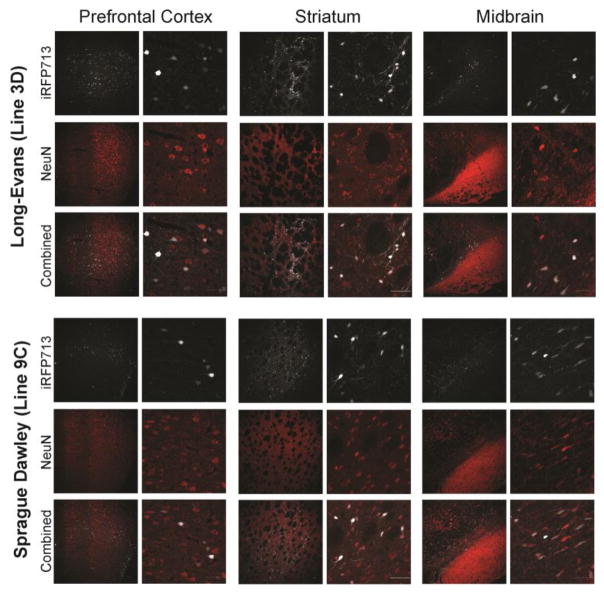

3.7 Characterization of Cre-dependent iRFP713 (DIO-iRFP) transgenic rat

LE-Tg(DIO-iRFP)3Ottc and SD Tg(DIO-iRFP)9Ottc were phenotyped for neuronal iRFP713 expression following AAV1-GFP-Cre delivery to striatum, cortex and midbrain. Coronal brain sections from AAV1-GFP-Cre injected animals were immunostained for NeuN (Figure 8). AAV serotype 1 primarily transduces neurons when delivered to the adult rat brain. AAV1-GFP-Cre transduction resulted in iRFP713 expression in neuronal cell bodies and processes in all three regions tested. Additionally, a subset of cells that expressed iRFP713 were negative for NeuN (Figure 8 panels).

Figure 8. DIO-iRFP transgenic rats express iRFP713 in a Cre-dependent manner in three different brain regions.

Representative images of the iRFP expression in phenotypically positive Long-Evans (top panel) and Sprague-Dawley (bottom panel) DIO-iRFP transgenic rats. DIO-iRFP line 3D (Long-Evans) and 9C (Sprague-Dawley) rats were injected in the prefrontal cortex (left), striatum (middle), and midbrain (right) with AAV1-GFP-Cre. Immunohistochemistry for NeuN was used to indicate neurons, which colocalized with iRFP expression. Scale bars are 50 μm.

Offspring of crosses between lines LE-Tg(DIO-iRFP)3Ottc and LE-Tg(DAT::iCre)1Ottc that were genotyped positive for both the iRFP713 and Cre transgenes were analyzed for co-expression. Confocal analysis of anti-Cre and anti-TH immunostained midbrain sections showed that Cre localized to TH+ cells >99%, but not all Cre positive cells were also positive for iRFP713 (Figure 9). However, nearly all iRFP713 expressing cells co-localized with TH (95.9±0.2%).

Figure 9. Progeny of DAT-iCre and DIO-iRFP rat cross selectively express iRFP713 in dopaminergic neurons in midbrain.

Fixed coronal brain sections containing the midbrain of (A) DIO-iRFP rat without Cre or (B) double transgenic rat brain (DIO-iRFP x DAT-iCre) were scanned using an NIR scanner at 700 nm. Confocal images of ventral tegmental area (VTA) of a double transgenic rat brain stained for anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (C, FITC, green) and anti-Cre recombinase (D, TRITC, red) as well as the intrinsic iRFP fluorescence (E, Cy5, white). All three channels were merged to create (F). Scale bar for confocal images is equivalent to 50 μm.

4. Discussion

iRFP713 has properties that are equivalent or superior to the GFP-like FPs used as reporters in neuroscience research, with the additional benefit of utilizing wavelengths that are minimally absorbed by water, hemoglobin and melanin. GFP and its derivatives use an intrinsic chromophore formed through interactions of its constituent amino acids, however, the chromophore for iRFP713 is product of heme metabolism, biliverdin (BV). Although this requirement for an extrinsic chromophore presented a major obstacle for the visualization of IFP1.4 and IFP2.0, we demonstrate that the amount of endogenous BV that is available in neurons is adequate for iRFP713 fluorescence. This was true for cultured human SH-SY5Y cells and rat primary cortical neurons, as well as in vivo when iRFP713 was expressed in the rodent brain, and has also been demonstrated in other cell and tissue types12,16–18. iRFP713 is readily detectable when trafficked to the cytosol, nucleus, plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria in our neuronal cell culture models. Although we did not determine whether BV is present in those subcellular compartments per se, or that iRFP713 conjugates to BV while en route to a subcellular compartment, we demonstrate that iRFP713 can fluoresce when partitioned into these subcellular compartments without the addition of exogenous BV.

When optogenetic effectors channelrhodopsin or halorhodopsin were translationally fused to iRFP713, the iRFP713 fluorescence remained detectable in rat neuronal cultures and in rat and mouse brains18. This included the labeling of processes in primary cortical neurons in vitro and the striatal fibers from dopaminergic neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway in vivo. The expression of iRFP713 was also detected in a live, anesthetized mouse using two-photon imaging, where labeled neurons were observable in the cortex up to a depth of 200–300 μm. These data demonstrate the successful expression and detection of iRFP713 in neurons from the mouse and rat brain.

The optimal two-photon excitation peak for iRFP713 is at ~1280 nm12, and lies beyond the output range of conventional Ti:Sapphire-based femtosecond lasers. To excite iRFP713 most efficiently, a two-photon source incorporating an optical parametric oscillator (e.g., InSight® from Spectra-Physics or Chameleon Discovery from Coherent, up to 1300nm output) is preferred. We chose to excite iRFP713 at 920nm to utilize the shorter-wavelength output of the more commonly used Ti:Sapphire laser, where the observed two-photon excitation is likely mediated by the blue-shifted minor transitions17. The fact that iRFP713-positive neurons can be detected under the nonoptimal excitation condition suggests that even better imaging quality and depth would be achieved, if 1280nm excitation were used.

The detection of fluorescence and proper localization of the translational fusions is somewhat surprising given that iRFP713 predominantly exists as a dimer in its purified form12. It is unclear whether the various translational fusion proteins with iRFP713 are forming dimers in vivo or in vitro, but if dimerization occurred, it did not remove the activity of channelrhodopsin (Figure 7). The aggregation observed with the halorhodopsin-iRFP713 suggests that this fusion causes to a disruption in the synthetic trafficking signals32, and may be alleviated by upgrading the reporter to one of the newly developed monomeric variants16.

The benefit of using an opsin-iRFP fusion protein over an opsin-EYFP fusion protein is that it allows one to safely identify or image the labeled neurons in a living sample using a wavelength that will not trigger the opsin channel to open. For example, an opsin fused to EYFP may be activated when searching for a EYFP-positive cell but the wavelength of light used to excite iRFP713 does not fall in the excitation spectrum of most blue and green light opsins.

Based on the electrophysiological properties that we examined, iRFP713- and EYFP-expressing dopamine neurons in the midbrain functioned similarly. mCherry-expressing dopamine neurons, however, had lower input resistance than EYFP- or iRFP713-expressing neurons and exhibited a wide variability in the amount of current required to hold the cell at a steady membrane potential. Low input resistance and large or variable holding current are often indicators of poor or unstable cell health. We obtained data from fewer mCherry-expressing neurons overall due to the difficulty of recording from this population, despite that a similar number of attempts were made to record from these neurons. Although it is possible that some of the variability in holding current and input resistance could be due to low sample size, the fact that fewer successful recordings were obtained per number of attempts provides additional support for the idea that poor cell health in the mCherry-expressing neurons contributes to variability in cell properties. Thus, it is possible that prolonged expression of the fluorescent reporter mCherry may have cytotoxic effects, and represents a major confound in studies of living cells. This is not unexpected, as previous in vivo and in vitro studies have noted alterations in protein stability and development following expression of mCherry33,34. Properties of neurons expressing EYFP or iRFP713 did not differ from dopamine neurons not expressing any fluorescent reporter, confirming that expression of these proteins does not significantly impact the functional properties of dopamine neurons. The influence of expression on electrophysiological parameters for other neuronal types was not tested.

In addition to examining the electrophysiological properties of dopamine neurons as a measure of iRFP-related toxicity, we used an MTS assay to measure viability of cultured primary cortical neurons transduced with AAV vectors expressing iRFP713 and EYFP alone or as translation fusions to opsins. We did observe a virus dose-dependent decrease in viability which we have previously reported24, but there was no difference whether iRFP713 or EYFP was present. We also saw no signs of phototoxicity using 30 min of constant light exposure (FITC or Cy5.5 filtered) for cells expressing iRFP713, EYFP or no fluorescent protein. In contrast, the photostability of iRFP713 was far superior to that of EYFP, with iRFP713 fluorescent signal decreasing less than 2% decrease after 30 minutes of constant light and EYFP signal decreasing 60%. The relatively low toxicity and high photostability make iRFP713 a useful fluorescent tag for neuronal studies.

Using an NIR scanner, iRFP713 expression can be measured in 96-well plates or microscopy slides containing cells or tissue, respectively. This provides a relatively “high throughput” method to assess reporter expression intensity or location at the cellular or tissue level. For example, to verify the injection site of a viral vector encoding iRFP713 in the rodent brain, multiple slides and brain sections can be examined with subsequent high resolution imaging using a properly equipped microscope. Using a 96-well plate of neuronal cells, we chemically induced an increase in expression of iRFP713 driven by a c-fos promoter which is used as a marker for neuronal activity35. Such an approach could be adapted to screen for drugs or genes that alter neuronal activation. Additionally, whole-animal scanners have been used to monitor iRFP in the whole body but not the brain36,37. Further studies are needed to evaluate the potential for in vivo monitoring of c-fos expression by brain region or longitudinally monitoring the loss of neuronal populations in models of neurodegeneration.

Here, we described the generation and characterization of Cre-dependent transgenic rats on two different background strains, Long Evans and Sprague-Dawley. Injection of AAV-Cre to the striatum, cortex, and midbrain of both lines of DIO-iRFP transgenic rats yielded widespread iRFP713 expression near the site of injection. Additionally, we demonstrate iRFP713 expression in TH+ cells in progeny resulting from the cross of the LE-Tg(DIO-iRFP)3Ottc and LE-Tg(DAT::iCre)1Ottc transgenic animals. A small subset of iRFP+ cells did not demonstrate NeuN immunoreactivity, perhaps suggesting the ability of other cell types in the CNS of DIO-iRFP transgenic animals to express iRFP713. It is possible, however, that these iRFP+/NeuN- cells are indeed neurons, as NeuN is not a reliable marker for all neural subtypes in different physiological conditions38–40, and has been shown to have especially inconsistent labelling of dopaminergic neurons in the rat substantia nigra41, which we have examined in the present study. When examining iRFP713 expression in TH+ cells in the midbrain of double transgenic rats, we also observed a subset of neurons that were Cre-positive but iRFP713-negative. These data suggested that either the location of the integrated transgene(s) do not allow recombination in all Cre-expressing cells, or cellular levels of BV vary and are not adequate for detection of iRFP713 in all dopamine neurons.

However, the lack of fluorescent reporter activity could be a result of Cre toxicity reducing the health of cell to support iRFP expression42–44. The two novel Cre-dependent transgenic rats described herein can be useful as fluorescent reporter animals, taking advantage of the previously described advantages of iRFP713 as an appropriate fluorophore to be utilized in the central nervous system. The DIO-iRFP rat lines can be used in conjunction with exogenously delivered Cre recombinase, or crossed with a Cre-driver transgenic line, as demonstrated in the present study. Fluorescent reporter activity can be easily assessed using an NIR scanner.

In summary, we have created a collection of tools in the form of viral vectors and transgenic rats to facilitate the use of iRFP713 as a superior alternative to GFP-like FPs for the tagging of opsins in the optogenetic manipulation of neurons.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Characterization of novel rat strains with Cre-dependent iRFP713 expression

iRFP713 can be expressed and detected within the neurons of the brain without exogenous biliverdin

iRFP713 can be conjugated to channelrhodopsin for detection without activation in optogenetic experiments

iRFP713 performance is consistent with conventional fluorescent reporter proteins

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute on Neurological Disease and Stroke, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and National Institute of Mental Health. KWW was supported by the US Army Research Laboratory, through DRI16-HR-023. We acknowledge Dr. Francois Vautier, Dr. Mark Verdecia, Mrs. Jeanne Pieper, Dr. Nick Edwards, and Ms. Grace Yeh for their technical contributions and Ms. Janette Lebron for editing and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rodriguez EA, et al. The Growing and Glowing Toolbox of Fluorescent and Photoactive Proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2017;42:111–129. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shcherbakova DM, Subach OM, Verkhusha VV. Red Fluorescent Proteins: Advanced Imaging Applications and Future Design. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:10724–10738. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filonov GS, et al. Deep-Tissue Photoacoustic Tomography of a Genetically Encoded Near-Infrared Fluorescent Probe. Angew Chem. 2012;51(6):1448–1451. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaberniuk AA, Shemetov AA, Verkhusha VV. A bacterial phytochrome-based optogenetic system controllable with near-infrared light. Nat Methods. 2016;13:591–597. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shcherbakova DM, Baloban M, Verkhusha VV. Near-infrared fluorescent proteins engineered from bacterial phytochromes. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2015;27:52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weissleder R. A clearer vision for in vivo imaging. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:316–317. doi: 10.1038/86684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shu X, et al. Mammalian Expression of Infrared Fluorescent Proteins Engineered from a Bacterial Phytochrome. Science. 2009;324:804–807. doi: 10.1126/science.1168683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maines MD. Heme oxygenase: function, multiplicity, regulatory mechanisms, and clinical applications. FASEB J. 1988;2:2557–2568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu D, et al. An improved monomeric infrared fluorescent protein for neuronal and tumour brain imaging. Nat Commun. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen K, Gunter K, Maines MD. Neurons Overexpressing Heme Oxygenase-1 Resist Oxidative Stress-Mediated Cell Death. J Neurochem. 2001;75:304–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeda A. Overexpression of Heme Oxygenase in Neuronal Cells, the Possible Interaction with Tau. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5395–5399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filonov GS, et al. Bright and stable near-infrared fluorescent protein for in vivo imaging. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:757–761. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deliolanis NC, et al. Deep-Tissue Reporter-Gene Imaging with Fluorescence and Optoacoustic Tomography: A Performance Overview. Mol Imaging Biol. 2014;16:652–660. doi: 10.1007/s11307-014-0728-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiguet-Jiglaire C, et al. Noninvasive near-infrared fluorescent protein-based imaging of tumor progression and metastases in deep organs and intraosseous tissues. J Biomed Opt. 2014;19:016019. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.19.1.016019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran MTN, et al. In Vivo image Analysis Using iRFP Transgenic Mice. Exp Anim. 2014;63:311–319. doi: 10.1538/expanim.63.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shcherbakova DM, et al. Bright monomeric near-infrared fluorescent proteins as tags and biosensors for multiscale imaging. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12405. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shcherbakova DM, Verkhusha VV. Near-infrared fluorescent proteins for multicolor in vivo imaging. Nat Methods. 2013;10:751–754. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang K, et al. Direct wavefront sensing for high-resolution in vivo imaging in scattering tissue. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7276. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fyk-Kolodziej B, Hellmer CB, Ichinose T. Marking cells with infrared fluorescent proteins to preserve photoresponsiveness in the retina. BioTechniques. 2014;57 doi: 10.2144/000114228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollander JM, Thapa D, Shepherd DL. Physiological and structural differences in spatially distinct subpopulations of cardiac mitochondria: influence of cardiac pathologies. AJP Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307:H1–H14. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00747.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein R, et al. Efficient Neuronal Gene Transfer with AAV8 Leads to Neurotoxic Levels of Tau or Green Fluorescent Proteins. Mol Ther. 2006;13:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chuong AS, et al. Noninvasive optical inhibition with a red-shifted microbial rhodopsin. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1123–1129. doi: 10.1038/nn.3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barth AL. Alteration of Neuronal Firing Properties after In Vivo Experience in a FosGFP Transgenic Mouse. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6466–6475. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4737-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howard DB, Powers K, Wang Y, Harvey BK. Tropism and toxicity of adeno-associated viral vector serotypes 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 in rat neurons and glia in vitro. Virology. 2008;372:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson MJ, Wires ES, Trychta KA, Richie CT, Harvey BK. SERCaMP: a carboxy-terminal protein modification that enables monitoring of ER calcium homeostasis. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25:2828–2839. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-06-1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henderson MJ, Richie CT, Airavaara M, Wang Y, Harvey BK. Mesencephalic Astrocyte-derived Neurotrophic Factor (MANF) Secretion and Cell Surface Binding Are Modulated by KDEL Receptors. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:4209–4225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.400648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalderon D, Roberts BL, Richardson WD, Smith AE. A short amino acid sequence able to specify nuclear location. Cell. 1984;39:499–509. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90457-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanford RE, Kanda P, Kennedy RC. Induction of nuclear transport with a synthetic peptide homologous to the SV40 T antigen transport signal. Cell. 1986;46:575–582. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90883-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roderick HL, Campbell AK, Llewellyn DH. Nuclear localisation of calreticulin in vivo is enhanced by its interaction with glucocorticoid receptors. FEBS Lett. 1997;405:181–185. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moriyoshi K, Richards LJ, Akazawa C, O’Leary DD, Nakanishi S. Labeling Neural Cells Using Adenoviral Gene Transfer of Membrane-Targeted GFP. Neuron. 1996;16:255–260. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rizzuto R, Brini M, Pizzo P, Murgia M, Pozzan T. Chimeric green fluorescent protein as a tool for visualizing subcellular organelles in living cells. Curr Biol. 1995;5:635–642. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gradinaru V, Thompson KR, Deisseroth K. eNpHR: a Natronomonas halorhodopsin enhanced for optogenetic applications. Brain Cell Biol. 2008;36:129–139. doi: 10.1007/s11068-008-9027-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snaith HA, Anders A, Samejima I, Sawin KE. Methods in Cell Biology. Vol. 97. Elsevier; 2010. pp. 147–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shemiakina II, et al. A monomeric red fluorescent protein with low cytotoxicity. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1204. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgan JI, Curran T. Stimulus-Transcription Coupling in the Nervous System: Involvement of the Inducible Proto-Oncogenes fos and jun. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1991;14:421–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.14.030191.002225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Filonov GS, Verkhusha VV. A Near-Infrared BiFC Reporter for In Vivo Imaging of Protein-Protein Interactions. Chem Biol. 2013;20:1078–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rice WL, Shcherbakova DM, Verkhusha VV, Kumar ATN. In Vivo Tomographic Imaging of Deep-Seated Cancer Using Fluorescence Lifetime Contrast. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1236–1243. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mullen RJ, Buck CR, Smith AM. NeuN, a neuronal specific nuclear protein in vertebrates. Development. 1992;116:201–211. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gusel’nikova VV, Korzhevskiy DE. NeuN as a neuronal nuclear antigen and neuron differentiation marker. Acta Naturae Англоязычная Версия. 2015;7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ünal-Çevik I, Kılınç M, Gürsoy-özdemir Y, Gurer G, Dalkara T. Loss of NeuN immunoreactivity after cerebral ischemia does not indicate neuronal cell loss: a cautionary note. Brain Res. 2004;1015:169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cannon JR, Greenamyre JT. NeuN is not a reliable marker of dopamine neurons in rat substantia nigra. Neurosci Lett. 2009;464:14–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loonstra A, et al. Growth inhibition and DNA damage induced by Cre recombinase in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:9209–9214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161269798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pfeifer A, Brandon EP, Kootstra N, Gage FH, Verma IM. Delivery of the Cre recombinase by a self-deleting lentiviral vector: efficient gene targeting in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:11450–11455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201415498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gangoda L, et al. Cre transgene results in global attenuation of the cAMP/PKA pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e365. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.