Abstract

Introduction

Cross-sectional research suggests that neighborhood characteristics and transportation access shape unmet need for medical care. This longitudinal analysis explores relationships of changes in neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and transportation access to unmet need for medical care.

Methods

We analyzed seven waves of data from African American adults (N = 172) relocating from severely distressed public housing complexes in Atlanta, Georgia. Surveys yielded individual-level data and administrative data characterized census tracts. We used hierarchical generalized linear models to explore relationships.

Results

Unmet need declined from 25% pre-relocation to 12% at Wave 7. Post-relocation reductions in neighborhood disadvantage were inversely associated with reductions in unmet need over time (OR = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.51–0.99). More frequent transportation barriers predicted unmet need (OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.02–1.31).

Conclusion

These longitudinal findings support the importance of neighborhood environments and transportation access in shaping unmet need and suggest that improvements in these exposures reduce unmet need for medical care in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Public housing relocations, unmet need for medical care, transportation access, neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage

Access to health care is a critical component of achieving health equity in the United States (U.S.) and a major goal of Healthy People 2020 and of the Affordable Care Act.1,2 Unmet need for medical care (“unmet need”) results in increased morbidity, mortality, and long-term health care costs.1,3 Impoverished populations and racial/ethnic minorities bear a disproportionate burden of illness; these groups are also less likely to have adequate access to health care.2,4–6

An emerging line of research suggests that neighborhood poverty and transportation access shape unmet need for medical care among U.S. adults. Neighborhood poverty is associated with unmet need for medical care.7,8 Disadvantaged areas may face challenges attracting and maintaining health care resources, such as health care providers.9,10 However, the vast majority of studies that have explored relationships of neighborhood characteristics to unmet need for medical care use ecological7 or multilevel cross-sectional designs,8,9,11–13 which limit our ability to assess causality. Adequate transportation is fundamental to health care utilization.14–18 Individuals report poorer health when transportation problems impede their ability to reach care; individuals who report transportation barriers to care are more likely to be female, poor, less educated, and to belong to a racial/ethnic minority than those who were able to travel to care.16,19 Most studies that have explored the relationship of transportation access to unmet need for medical care use individual-level measures of transportation (e.g., self-reported transportation barriers).14–18 Neighborhood access to transportation (e.g., public transportation access, the density of privately-owned vehicles that could be borrowed) may be particularly important for impoverished populations. Poor people are less likely to own, or have access to, a personal vehicle to get to work than the population as a whole and are more likely to rely on public transportation, walk, or use other transportation modes.20 Perhaps as a result, natural experiments (e.g., mass transportation strikes) suggest that area-level changes in transportation access are associated with changes in health care utilization among impoverished populations.19,21,22

This longitudinal, multilevel study explores (1) trends in the odds of unmet need for medical care in the sample over time and (2) the extent to which neighborhood-level socioeconomic disadvantage and neighborhood- and individual-level transportation are associated with the odds of unmet need for medical care over time. We studied this topic in a predominately substance-misusing sample of African American adults who were being relocated from highly distressed public housing complexes in Atlanta, Georgia (GA).23,24 Between 1994 and 2013, 50,000 residents living in highly distressed public housing complexes in Atlanta were relocated under Housing Opportunities for Everyone (HOPEVI) and Section 18 of the 1937 Housing Act.25 Following the relocations, most residents moved to voucher-subsidized rental units scattered across the region, and the housing complexes were destroyed.24

People living in public housing have some of the poorest health profiles of any group in the U.S.26,27 In addition, residents may belong to highly stigmatized groups (e.g., substance users), which may affect health and make it difficult to access medical care.28–31 Research suggests that relocaters experienced post-relocation improvements in mental and physical health and had lower rates of substance use and sexual risk behaviors post-relocation.23,32–36 To our knowledge, no studies have explored the impact of relocations on unmet need for medical care over time. Our own research suggests that relocaters did not experience significant improvements in unmet need for medical care immediately following relocations.37 In addition, travel distance to safety-net primary health care clinics increased immediately following relocations, which may have resulted in greater barriers to medical care.38 However, relocations also brought people to qualitatively different neighborhoods, which in the main were less violent and less impoverished than the neighborhoods containing the complexes.24 These communities may have more resources and prosocial norms supporting health care seeking and preventative behaviors.13,35,36,39,40

The present analysis seeks to:

Evaluate temporal trends in the odds of unmet need for medical care, and explore whether trends vary by gender or drug/alcohol dependence. (Note: By design, the study oversampled substance misusers.32 Similarly, health care utilization varies by gender.41);

Investigate relationships of changes in exposure to neighborhood-level socioeconomic disadvantage and individual- and neighborhood-level transportation access to the odds of unmet need for medical care, and explore whether relationships vary by gender or drug/alcohol dependence.

This analysis (Figure 1) was guided by the Gelberg-Andersen Model for Vulnerable Populations (G-AMVP).42 The G-AMVP has been used successfully to describe predisposing, enabling, and need predictors of health care utilization among precariously housed populations and substance users in the U.S.43–46 Predisposing characteristics include individual-level factors that exist prior to the perception of illness, including sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., gender) and variables that reflect vulnerability, such as housing. Need includes factors that may initiate health care seeking, such as perceived health status. Enabling characteristics include factors that may serve as facilitators or barriers to care, such as neighborhood resources (e.g., transportation).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of relationships between neighborhood disadvantage, transportation access and unmet need for medical care.

Methods

This longitudinal multilevel study followed a predominately substance-misusing cohort of African American adults relocating from seven public housing complexes targeted for demolition in Atlanta, Georgia. All residents of these complexes were relocated to private market voucher-subsidized rental units, and the vacant complexes were demolished. Baseline (Wave 1) data captured pre-relocation conditions; Wave 2–7 captured post-relocation conditions in nine-month intervals. Institutional Review Board approval and a Certificate of Confidentiality were obtained prior to study implementation. Study methods have been described in detail elsewhere.23,32–34

Eligibility and sampling

Study eligibility criteria included: resident for >1 year in one of the seven public housing complexes targeted for demolition in the final wave of public housing relocations in Atlanta (2008–2010); self-identified as a non-Hispanic Black/African American adult (>18 years); sexually active in the past year; and not living with a current study participant. Because of the study’s overarching interest in understanding the impacts of relocations on drug use, we used quota sampling methods to construct a sample that varied with regard to baseline substance misuse: we sought to create a sample in which one-quarter of participants met criteria for drug/alcohol dependence; one-half misused substances but were not dependent (i.e., self-reported recent use of illicit drugs or alcohol misuse, including binge drinking), and one-quarter did not misuse substances (i.e., no illicit drug use in the past five years and no recent alcohol misuse).

Recruitment and retention

Study staff recruited onsite in each complex; community- and faith-based organizations near each complex distributed flyers; and participants could refer individuals for screening. Intensive retention methods, including calling participants monthly to maintain relationships and update contact information, incentives to remain in contact, and contacting network members when participants were difficult to reach, were implemented to keep attrition low and random.

Data collection

Individual-level data were gathered via Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI) survey at each wave. Participants received $20 for the baseline interview; incentives increased by $5 at each subsequent wave. Participant home addresses were geocoded to census tracts at each wave (2010 tract boundaries were used throughout), and administrative data were analyzed to describe characteristics of these tracts at each wave.

Measures

All individual-level measures were time-varying (reflecting the six-month reporting period prior to the interview) and binary unless otherwise specified. Baseline data described census tract characteristics pre-location. Tract-level data for Waves 2–7 was time-varying, and reflected the time period of data collection for that wave or the most proximate year for which data were available.

Outcome

Unmet need for medical care, the binary outcome of interest, was measured as a “yes” response to the question “During the past six months, was there a time that you wanted medical care but could not get it at that time?”47 When individuals were HIV-positive, survey questions assessing unmet need for medical care captured HIV-related care specifically. Given the small proportion of study participants with diagnosed HIV infection (fewer than 10%), this measure includes both HIV-uninfected participants reporting unmet need for general medical care and HIV-infected participants reporting unmet need for HIV-related medical care.

Exposures

Enabling exposure variables included census tract-level socioeconomic disadvantage and census tract- and individual-level transportation access.

Tract-level percent poverty, percent unemployed, percent adults older than 25 years without a high school diploma/GED, median household income, and the percent of residents who were Black were constructed using data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Longitudinal Tract Database, which maps 2000 tract data to 2010 boundaries.48 The locations of violent crimes were obtained from law enforcement agencies, geocoded to census tracts, and used to calculate the violent crime rate per 1,000 residents for each tract. Offenses within a 100-foot buffer of the tract boundary were included in the tract’s calculation.

Several tract-level predictors were correlated. To avoid multicollinearity in multivariable models, we used principal components analyses (PCA) to condense these correlated variables into components. The resulting component captured “tract-level socioeconomic disadvantage” (median household income, poverty rate, percent residents older than 25 without a high school diploma or GED, violent crime rate, and percent of residents who are Black; tracts with higher percentages of Black residents may be more disadvantaged due to historic, persistent structural discrimination in the U.S.49).

Tract-level transportation access was created using data from the U.S. Census Bureau. “Tract private vehicle access” was defined as the percent of employed Black residents (aged 16 and older) with access to at least one vehicle for transportation to work, as reported in the Census. “Tract public transportation access” was defined as the percent of employed Black residents (aged 16 and older) without access to a vehicle who reported using public transportation to get to work in the census. In addition to exploring the independent relationships of these two variables to unmet need for medical care, we also combined them to form a tract-level measure of “any transportation access,” which was the sum of the percentages of residents with private vehicle access and residents without access to a vehicle who used public transportation to get to work.

We created four measures of enabling individual-level transportation characteristics. These variables were “individual transportation barriers,” which captured the frequency that lack of transportation “caused problems” (ordinal); typical travel time to usual source of care in minutes (continuous); typical one-way travel cost to usual source of care in dollars (continuous); and typical mode of transportation to usual source of care (categorical).

Effect modifiers

Effect modifiers included self-identification as a woman and sub-stance (drug or alcohol) dependence, as measured by the Texas Christian University Drug Screen II.50

Other covariates

Covariates capturing other individual-level enabling characteristics included: perceived community violence (continuous),51 proportion of social network providing actual support;52 and baseline lifetime experience of discrimination in a medical setting.53 Predisposing characteristics included: age in years (continuous); married or living as married at baseline; any employment; less than a high school education at baseline; homeless; and number of months living in neighborhood (continuous). Need was measured as self-rated health (ordinal), using the SF-12 scale,54 and being HIV-infected.

Analysis

Distributions of all variables were assessed across waves. Plots were used to visualize proportion of unmet need for medical care over time, and whether trajectories varied by gender and substance dependence status.

We modeled relationships with hierarchical generalized linear models (HGLM) using a logit link in three stages to: 1) assess temporal trajectories in unmet need for medical care, and whether trajectories varied by gender or drug/alcohol dependence; 2) assess the relationship of each individual- and tract-level variable to unmet need for medical care, controlling for time (“bivariate analysis”); and 3) describe multivariable relationships. All HGLMs had three levels: level 1 was time, level 2 was the individual participant, and level 3 was the baseline tract. All HGLMs included a subject-specific intercept, a slope for time, and an interaction term for time and substance dependence. Time was measured as the number of months since Wave 2, the first post-relocation interview.

Continuous variables were centered at their baseline values, resulting in a baseline variable and a “change since baseline” measure for Waves 2–7. We determined a priori that the following variables were theoretically relevant and should be included in multivariable models, regardless of statistical significance in bivariate analyses: all tract-level variables, all individual-level transportation measures, age, gender, substance use, self-rated health, and length of stay in the neighborhood. Tract-level variables, individual-level transportation measures, gender, and substance use were included in multivariable models in order to assess the study aims. Similarly, length of stay in the neighborhood was retained in order to capture the potential disruption caused by relocations.25,27 Age and self-rated health were retained in multivariable models to control for health care utilization and need.1,26 Remaining variables with p-values < .05 were retained in the final model. Tract-level transportation variables (i.e., private vehicle, public transportation, and overall access) were correlated and as a result, modeled separately. We ran three multivariable models, each model included all individual-level variables, tract-level socioeconomic disadvantage, and one of the tract-level transportation variables.

Results

A total of 172 participants were enrolled at baseline, 86.2% of participants were retained at Wave 7. At Wave 1 (Table 1), participants were, on average, 43 years old (standard deviation [SD] = 14). Fifty-six percent (n = 96) were women. Sixty percent (n = 92) of participants reported having health insurance at baseline; this increased to 73% (n = 110) by Wave 7. Baseline characteristics of participants who completed Wave 7 (n = 149) were comparable to those of participants who did not complete Wave 7 (n =18) (data not shown).

Table 1.

DISTRIBUTIONS OF INDIVIDUAL- AND CENSUS-TRACT LEVEL CHARACTERISTICS AMONG 172 AFRICAN AMERICAN ADULTS RELOCATED FROM SEVEN PUBLIC HOUSING COMPLEXES IN ATLANTA, GEORGIA ACROSS 7 WAVES OF FOLLOW-UPa

| Characteristics of participants and census tracts | Wave 1 n (%) or Mean (SD) N = 171b |

Wave 2 n (%) or Mean (SD) N = 163 |

Wave 3 n (%) or Mean (SD) N = 160 |

Wave 4 n (%) or Mean (SD) N = 156 |

Wave 5 n (%) or Mean (SD) N = 158 |

Wave 6 n (%) or Mean (SD) N = 154 |

Wave 7 n (%) or Mean (SD) N = 149 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmet need for medical care | 42 (25.00) | 34 (21.79) | 27 (18.00) | 32 (21.48) | 19 (13.01) | 19 (12.58) | 18 (12.33) |

| Census tract level | |||||||

| Enabling characteristics | |||||||

| Socioeconomic disadvantage componentc | 0.97 (0.66) | −0.23 (0.92) | −0.26 (0.93) | −0.19 (0.96) | −0.20 (0.97) | −0.10 (0.98) | −0.10 (0.92) |

| Percent poverty | 46.03 (9.53) | 30.24 (11.85) | 30.17 (12.03) | 31.77 (12.78) | 30.88 (12.66) | 32.69 (13.72) | 32.78 (12.66) |

| Percent unemployment | 21.60 (5.51) | 17.01 (7.83) | 16.68 (7.56) | 18.12 (7.79) | 18.01 (7.80) | 19.61 (8.35) | 19.57 (7.93) |

| Percent residents >25 with less than high school education | 39.04 (10.38) | 19.10 (8.56) | 19.20 (8.76) | 18.42 (8.26) | 18.26 (8.01) | 17.97 (7.71) | 18.44 (7.86) |

| Median household income | 15,831.93 (4,472.43) | 33,476.02 (15,788.31) | 33,735.55 (15,928.69) | 33,530.83 (17094.31) | 34,408.44 (16,516.81) | 33,868.15 (16,616.57) | 33337.14 (16207.40) |

| Percent residents who are Non-Hispanic Black | 81.33 (17.48) | 74.01 (28.01) | 72.24 (28.72) | 73.79 (27.51) | 71.80 (29.66) | 73.26 (29.14) | 75.52 (27.35) |

| Violent crime rate (per 1,000) | 35.59 (15.78) | 20.73 (14.68) | 20.95 (14.44) | 20.71 (14.84) | 21.35 (15.14) | 21.38 (14.34) | 20.55 (13.59) |

| Percent employed Black workers 16+ with access to vehicle | 81.02 (9.17) | 84.63 (10.34) | 84.22 (11.45) | 84.44 (11.07) | 84.99 (11.54) | 85.07 (10.81) | 85.76 (10.49) |

| Percent employed Black workers 16+ without access to a vehicle who take public transport to work | 12.69 (7.75) | 10.04 (8.54) | 10.40 (9.44) | 9.65 (9.19) | 9.54 (9.43) | 9.36 (8.50) | 8.78 (8.36) |

| Percent employed workers 16+ with access to a vehicle or public transport | 93.71 (4.67) | 94.67 (4.41) | 94.62 (4.80) | 94.09 (4.52) | 94.53 (4.28) | 94.43 (4.62) | 94.55 (4.55) |

| Individual-level | |||||||

| Enabling characteristics | |||||||

| Frequency of barriers to transportationd | 3.14 (2.69) | 2.33 (2.62) | 1.71 (2.11) | 1.85 (2.22) | 1.76 (2.32) | 1.21 (1.97) | 1.64 (2.29) |

| Transportation time in minutes to usual source of care | 36.44 (23.78) | 38.82 (26.71) | 36.98 (27.48) | 39.71 (28.44) | 40.50 (32.91) | 35.95 (27.02) | 33.92 (26.30) |

| Transportation cost in dollars to usual source of care | 2.11 (2.56) | 12.21 (63.17) | 6.14 (37.52) | 9.37 (79.39) | 10.08 (74.77) | 2.57 (4.51) | 9.33 (70.86) |

| Transportation mode to usual source of care | |||||||

| Public transport | 105 (62.87) | 101 (65.58) | 77 (54.61) | 89 (60.96) | 82 (58.57) | 86 (60.14) | 66 (50.77) |

| Drive self or walk | 38 (22.75) | 32 (20.78) | 33 (23.40) | 29 (19.86) | 28 (20.00) | 31 (21.68) | 37 (28.46) |

| Someone else drives | 16 (9.58) | 7 (4.55) | 18 (12.77) | 16 (10.96) | 13 (9.29) | 16 (11.19) | 14 (10.77) |

| Taxi, ambulance, or other transport | 8 (4.79) | 14 (9.09) | 13 (9.22) | 12 (8.22) | 17 (12.14) | 10 (6.99) | 13 (10.00) |

| Perceived community violencee | 2.73 (2.20) | 0.61 (1.11) | 0.67 (1.22) | 0.58 (1.00) | 0.76 (1.28) | 0.88 (1.39) | 0.82 (1.45) |

| Proportion of social network providing support | 0.71 (0.26) | 0.67 (0.29) | 0.66 (0.32) | 0.62 (0.31) | 0.61 (0.32) | 0.62 (0.31) | 0.60 (0.31) |

| Lifetime experience of discrimination related to medical care | 28 (16.67) | 10 (6.33) | 9 (5.73) | 6 (3.97) | 9 (5.84) | 8 (5.30) | 1 (0.67) |

| Health insurance (Medicaid, Medicare, Private Insurance, Other) | 92 (59.74) | 115 (72.33) | 108 (68.79) | 105 (69.08) | 109 (70.78) | 111 (73.51) | 110 (72.85) |

| Predisposing Characteristics | |||||||

| Age (years) | 42.92 (13.96) | 43.91 (13.87) | 45.10 (13.98) | 46.24 (13.79) | 46.53 (13.79) | 46.91 (13.75) | 47.28 (13.82) |

| Married or living as married | 16 (9.47) | 14 (11.11) | 14 (8.92) | 13 (7.56) | 17 (11.04) | 15 (9.93) | 14 (9.27) |

| Employed (part, full, self-employed) | 19 (10.98) | 20 (12.50) | 30 (19.11) | 24 (15.89) | 30 (19.74) | 23 (15.23) | 30 (19.87) |

| Less than high school education | 65 (38.46) | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Homeless | 0 (0) | 7 (4.57) | 7 (4.67) | 3 (2.11) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.07) | 8 (5.88) |

| Months in the neighborhood | 111.80 (115.12) | 14.38 (44.39) | 65.67 (131.84) | 51.35 (107.06) | 49.85 (92.21) | 69.17 (106.71) | 58.11 (87.03) |

| Need | |||||||

| Self-rated healthf | 1.85 (1.01) | 1.86 (1.04) | 1.71 (1.08) | 1.95 (1.04) | 1.80 (1.12) | 1.74 (1.09) | 1.87 (1.07) |

| HIV-infectedg | 15 (8.88) | 16 (10.06) | 15 (9.55) | 17 (11.11) | 18 (11.61) | 16 (10.60) | 17 (11.26) |

| Effect Modifiers | |||||||

| Genderh | |||||||

| Woman | 96 (56.47) | 93 (58.13) | 90 (57.32) | 87 (56.86) | 88 (56.77) | 86 (56.95) | 87 (57.62) |

| Man | 74 (43.53) | 67 (41.88) | 67 (42.68) | 66 (43.14) | 67 (43.23) | 65 (43.05) | 64 (42.38) |

| Substance (drug or alcohol) dependenti | 33 (19.53) | 11 (6.88) | 18 (11.46) | 11 (7.19) | 10 (6.45) | 9 (5.96) | 11 (7.28) |

Variables capture behaviors/conditions in the previous 6 months unless otherwise noted.

172 participants were enrolled, however, baseline data were lost for one participant.

Includes median household income, percent poverty, percent residents >25 with less than high school education, percent unemployed, violent crime rate, and percent of residents who are non-Hispanic Black.

Self-reported frequency of transportation causing problems ranged from 0 to 8 where 0 represents no transportation problems and 8 represents almost daily transportation problems.

Perceived violence average of 5-items with 5 point likert scale, mean scores range from 0 to 5 with higher scores indicative of more frequent, severe community violence.

5-point likert scale ranging from 0 to 4, with lower scores indicative of better health.

Defined as a positive OraQuick ADVANCE Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test and confirmatory Westernblot.

Women included 3 individuals who were transgender (male to female).

Defined as a score of 3 or greater out of 9.

Participants dispersed from the seven census tracts where the public housing complexes were located at baseline to 94 tracts by Wave 7. Participants had moved an average of 7.33 miles (SD = 5.53) from their original housing complexes by Wave 7. On average, relocations brought participants to tracts with improved socioeconomic conditions, with the greatest improvements experienced between Waves 1 and 2. For example, prior to relocating, on average participants lived in tracts where 46% of households lived in poverty and where there were 35.6 violent crimes per 1,000 residents. By Wave 2, on average participants lived in tracts where a third of the households were living in poverty and there were 20.7 violent crimes per 1,000 residents. These improvements were sustained over time.

Travel-time to usual source of care remained relatively stable over time, though average travel costs increased by $7 from Wave 1 to 7, from $2.11 to $9.33. The majority of participants used public transportation to travel to their medical care provider at each wave, this proportion declined over time. Prior to relocations, 63% (n = 105) of participants used public transportation to travel to their medical provider, this decreased to 51% (n = 66) by Wave 7. Tract-level use of public transportation among workers without cars decreased (13% at Wave 1 to 9% at Wave 7), suggesting that participants moved to tracts with less access to public transportation than the tracts containing their public housing complex. In contrast, tract-level vehicle access tended to increase over time, ranging from 81% at Wave 1 to 86% at Wave 7.

Temporal trajectories in reported unmet need for medical care

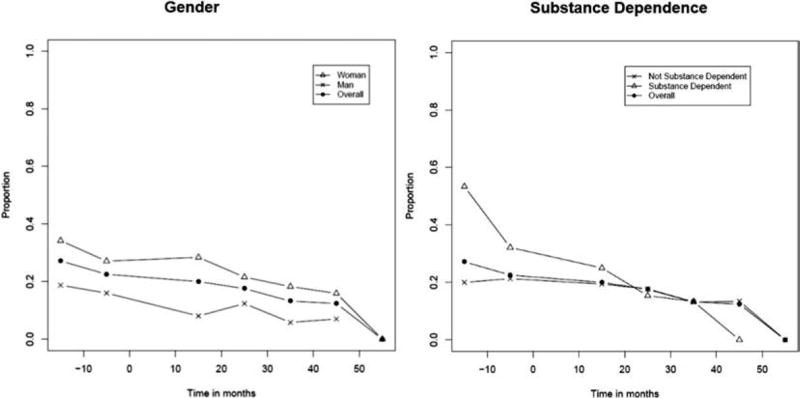

At baseline, 25% of participants reported unmet need for medical care, in the last six months. Unmet need for medical care, declined over time, with 12% reporting unmet needs for medical care at Wave 7. The proportion of unmet need for medical care declined linearly over time (Figure 2), with rates of decline similar for women and men. Although women consistently reported slightly higher unmet need for medical care across waves, these differences were not statistically significant. Substance-dependent participants reported higher proportion of unmet needs for medical care both prior to and immediately following relocations, but experienced steeper declines over time (Model 1: OR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.90–0.97).

Figure 2.

Proportion of African-American adults relocating from severely distressed public housing complexes in Atlanta, GA reporting unmet medical care needs over time, overall, by gender, and by substance dependence status.

Relationships of changes in exposure to neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and transportation access to unmet need for medical care

Change in tract-level socioeconomic disadvantage was not statistically significant in bivariate models (0.84, 95% CI = 0.63–1.10). Reductions in tract-level socioeconomic disadvantage were inversely associated with a lower odds of unmet need for medical care. Specifically, a one SD reduction in tract-level socioeconomic disadvantage was associated with an approximately 29% reduction in the odds of unmet needs for medical care (OR = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.51–0.99).

In bivariate models (Table 2, Model 2), post-relocation increases in the reported frequency of transportation barriers (OR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.00–1.22), and baseline cost of (OR = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.00–1.28) and travel time to medical provider (OR = 1.02, CI = 1.00–1.03) were significantly associated with greater odds of unmet need for medical care. In contrast, walking or driving to the health care provider was significantly associated with lower odds of unmet need for medical care (OR = 0.43, 95% CI = 0.21–0.90; Table 2, Model 2). In multivariable models, post-relocation increases in the frequency of self-reported barriers to transportation were associated with greater odds of unmet need for medical care (OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.02–1.31; Table 2, Model 3). All other individual-level transportation variables lost significance once potential confounders were included in the model (Table 2, Models 2 and 3).

Table 2.

BIVARIATE AND MULTIVARIABLE RELATIONSHIPS OF INDIVIDUAL- AND TRACT-LEVEL CHARACTERISTICS TO UNMET NEEDS AMONG A SAMPLE OF 172 AFRICAN AMERICAN ADULTS RELOCATED FROM SEVEN PUBLIC HOUSING COMPLEXES IN ATLANTA, GEORGIAa

| Characteristics of participants and census tracts |

Model 1: Growth Curve Model OR (95% CI) |

Model 2: Bivariate Modelsb OR (95% CI) |

Model 3: Multivariable Model AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time for not substance dependent | 0.98 (0.96–0.97) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | |

| Time for substance dependent | 0.93 (0.90–0.97) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | |

| Substance dependent | 1.03 (0.42–2.54) | 0.82 (0.24–2.73) | |

| Census tract-level | |||

| Enabling characteristics | |||

| Socioeconomic disadvantage component | |||

| Baseline | 0.84 (0.49–1.46) | 0.64 (0.39–1.06) | |

| Change since baseline | 0.84 (0.63–1.10) | 0.71 (0.56–0.99) | |

| Percent employed Black workers 16+ with access to vehicle | |||

| Baseline | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | — | |

| Change since baseline | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | — | |

| Percent employed Black workers 16+ without access to a vehicle who take public transport to work | |||

| Baseline | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) | — | |

| Change since baseline | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | — | |

| Percent employed Black workers 16+ with access to a vehicle or public transport | |||

| Baseline | 1.02 (0.94–1.11) | 0.97 (0.90–1.06) | |

| Change since baseline | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | 0.97 (0.91–1.04) | |

| Individual-level | |||

| Enabling characteristics | |||

| Frequency of barriers to transportation | |||

| Baseline | 1.27 (1.11–1.45) | 1.02 (0.89–1.17) | |

| Change since baseline | 1.11 (1.00–1.22) | 1.16 (1.02–1.31) | |

| Transportation time in minutes to provider | |||

| Baseline | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | |

| Change since baseline | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | |

| Transportation cost in dollars to provider | |||

| Baseline | 1.13 (1.00–1.28) | 1.02 (0.91–1.15) | |

| Change since baseline | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | |

| Transportation mode to provider (ref = public transport) | |||

| Drive self or walk | 0.43 (0.21–0.90) | 1.17 (0.55–3.64) | |

| Someone else drives | 1.44 (0.64–3.23) | 1.70 (0.52–2.62) | |

| Taxi, ambulance, or other transport | 1.55 (0.68–3.52) | 1.33 (0.38–4.68) | |

| Perceived community violence | |||

| Baseline | 1.15 (0.96–1.38) | 1.08 (0.89–1.29) | |

| Change since baseline | 1.02 (0.89–1.18) | 1.10 (0.91–1.31) | |

| Proportion of social network providing support | |||

| Baseline | 1.34 (0.32–5.25) | 1.08 (0.28–4.15) | |

| Change since baseline | 1.02 (0.46–2.24) | 1.03 (0.41–2.62) | |

| Lifetime experience of discrimination in a medical setting (baseline) | 3.74 (1.59–8.82) | 2.61 (1.20–5.69) | |

| Health insurance | 0.38 (0.22–0.64) | 0.50 (0.27–0.92) | |

| Predisposing characteristics | |||

| Age in years | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) | |

| Man | 0.26 (0.13–0.54) | 0.23 (0.11–0.50) | |

| Married or living as married (baseline) | 0.51 (0.20, 1.28) | — | |

| Employed (baseline) | 0.94 (0.47–1.91) | — | |

| Less than high school education (baseline) | 2.43 (1.19–4.98) | 1.80 (0.94–3.46) | |

| Homeless | 2.36 (1.15–4.88) | 1.42 (0.55–3.64) | |

| Number of months in the neighborhood | |||

| Baseline | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | |

| Change since baseline | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | |

| Need | |||

| Self-rated health | |||

| Baseline | 1.29 (0.86–1.93) | 1.12 (0.73–1.70) | |

| Change since baseline | 0.99 (0.74–1.32) | 0.94 (0.64–1.37) | |

| HIV-infected | 0.08 (0.02–0.40) | 0.21 (0.04–1.03) | |

Relationships were modeled using hierarchical generalized linear models. Covariates captured behaviors/conditions in the past 6 months and were treated as time-varying unless noted otherwise.

Bivariate models included time and the interaction with substance dependence.

Measures of tract-level neighborhood transportation access were not associated with the outcome in bivariate or multivariable models (Table 2, Models 2 and 3).

The magnitudes and directions of tract-level socioeconomic disadvantage, and individual- and tract-level transportation were comparable across the three multivariable models (available from the first author upon request), though the relationship between socioeconomic disadvantage and unmet need for medical care was borderline statistically significant for models including tract-private vehicle ownership (OR = 0.60, 95 CI: 0.36–1.00) and not statistically significant for models including tract-level public transportation access (OR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.54–1.10).] Relationships were not moderated by gender or substance misuse status.

Notably, baseline lifetime experience of discrimination in a medical setting was associated with greater odds of unmet need for medical care. Participants that experienced prior medically-related discrimination had nearly three times the odds of reporting unmet need for medical care as compared to those that did not (OR = 2.61, 95% CI = 1.20–5.69).

Discussion

This multilevel, longitudinal analysis suggests that African American adults relocating from severely distressed public housing complexes in Atlanta, Georgia experienced reductions in unmet need for medical care over time, and that these changes were associated with post-relocation changes in the neighborhoods where these adults lived and in their transportation access. Specifically, in this sample post-relocation improvements in neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and post-relocation declines in individual-level transportation barriers predicted reductions in unmet need for medical care over time.

In contrast to past studies that have found immediate improvements in depression and substance use following relocations,23,32 improvements in unmet need for medical care were gradual: 25% of participants reported unmet need for medical care at Wave 1, 21% reported unmet need for medical care by Wave 4, and 12% reported unmet need for medical care by Wave 7. During the months following the relocations, participants may have been unable to prioritize seeking needed medical care because of immediate competing demands (e.g., procuring housing).25,27,55

Although there is a notable literature supporting the association of transportation barriers to unmet needs for medical care, particularly for impoverished populations, evidence regarding the contribution of specific transportation barriers (e.g., distance) is mixed.14 In our study, post-relocation declines in the frequency of self-reported barriers to transportation were associated with lower odds of unmet need for medical care. The majority of participants relied on public transportation to travel to their usual source of care and relocations brought participants to census tracts with lower access to public transportation. However, tract-level transportation access variables were not statistically significantly related to unmet need for medical care. Atlanta is an automobile-centric area that lacks a strong, integrated public transportation system.17,56 Mode of transportation to work may not reflect mode of transportation to health care. Additionally, patterns of transportation use may vary for employed and unemployed individuals, and many study participants were unemployed. Alternative measures of neighborhood transportation access, such as density and frequency of public transport, may more accurately capture area-level transportation access. However, these measures are not readily available for public use. One interpretation of our results is that, over time, participants either identified alternative modes of travel (e.g., borrowing a car from a new neighbor) to pre-relocation providers or found a new source of care that was closer to their new home.

Neighborhood poverty has been associated with unmet need for medical care in ecologic and cross-sectional studies.7,8 In our longitudinal study, a one SD improvement in the tract socioeconomic disadvantage component was associated with an approximately 29% reduction in the odds of unmet need for medical care. Participants relocating to less socioeconomically disadvantaged communities may have experienced more resourced and cohesive communities;35,36 these communities may have more prosocial norms around health care seeking and greater trust in providers.13,39,40 Community collective efficacy (i.e., the capacity of a community to work together towards a common good)51 is associated with fewer barriers to accessing health care and greater trust in providers.11,13

Notably, participants who experienced discrimination in a medical setting in their lifetime had nearly three times the odds of reporting unmet need for medical care as compared to those who did not. Past experiences of discrimination may serve as a significant barrier to seeking care, particularly for groups with multiple stigmatizing behaviors or conditions (e.g., substance users, public housing residents).28–31 Public housing recipients have been refused care due to their Medicaid status.57 Experiences of discrimination are associated with greater unmet need for medical care and lower quality of care and trust in providers.29 Notably, spatial access to safety-net clinics declined as a result of relocation,58 suggesting that relocaters may require extra support in identifying and linking to culturally relevant care accepting public insurance.

Limitations

These findings should be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. We could not randomly select residents from the complexes because no sampling frame of substance misusers in the complexes existed. Additionally, we could not use targeted sampling or respondent-driven sampling, which rely on network-based recruiting,59,60 because relocations were underway when recruitment began and so networks had been disrupted. However, our sample’s sociodemographic composition was similar to those of the underlying populations of residents in each of the seven complexes.32 Similarly, we could not create a control group of non-relocaters for this study: no severely distressed complexes remained in Atlanta at the time of data collection, and the non-distressed complexes that remained had very different resident demographics and were located in qualitatively different neighborhoods. It is possible that the reductions in unmet need for medical care observed here were driven by historical changes in Georgia, though the Affordable Care Act was not implemented until 2014 (after the vast majority of data collection) and Georgia elected not expand Medicaid.61 It is possible that improvements in unmet needs for medical care may have also been associated with improvements in health more generally. However, self-rated health remained stable across waves and was not associated with unmet need for medical care in multivariable models.

Conclusion

This study has multiple strengths. Its retention rate was high, despite the inclusion of active substance users and a highly mobile cohort. This high retention rate supports the internal validity of our findings. It is also the first to examine multilevel, longitudinal relationships of neighborhood characteristics to unmet need for medical care among U.S. adults and among relocaters specifically. Collectively, these findings, generated by a longitudinal, multilevel analysis, support the importance of neighborhood environments and transportation access in shaping unmet need for medical care in vulnerable populations, and suggest that improvements in these exposures reduce unmet need for medical care in a highly vulnerable population. Screening for transportation access and neighborhood conditions may help to identify populations at risk for unmet need for medical care. Similarly, addressing transportation-related barriers to care and helping individuals identify accessible, culturally relevant providers may help to reduce unmet need for medical care in this highly vulnerable population.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by three grants: a CFAR03 grant awarded by the Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409); a NIDA grant entitled “Public Housing Relocations: Impact on Healthcare Access, Drug Use & Sexual Health” (R21DA027072); and a NIDA grant entitled “Public Housing Relocations: Impact on HIV and Drug Use” (R01DA029513). Ms. Haley’s time was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number F31MH105238 and the George W. Woodruff Fellowship of the Laney Graduate School. We would like to thank our NIDA Project Officer, Dr. Bethany Deeds, for her excellent help with this project; Atlanta Housing Authority for permitting us to recruit participants on site; and study participants for sharing their time and experiences with the study. We would also like to thank Drs. Erin Ruel and Deidre Oakley for their insights into serial displacement and relocaters’ health and Dr. Janet Cummings for her insights on health care access. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Danielle F. Haley, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University, Atlanta, GA.

Sabriya Linton, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University, Atlanta, GA.

Ruiyan Luo, Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health at Georgia State University in Atlanta.

Josalin Hunter-Jones, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University, Atlanta, GA.

Adaora A. Adimora, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, UNC School of Medicine and Department of Epidemiology, UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

Gina M. Wingood, Department of Sociomedical Sciences, Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion, Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University in New York City.

Loida Bonney, Division of General Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

Zev Ross, ZevRoss Spatial Analysis in Ithaca, NY.

Hannah L.F. Cooper, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University, Atlanta, GA.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Leading health indicators for healthy people 2020: letter report. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. Committee on Leading Health Indicators for Healthy People 2020. Available at: https://www.nap.edu/read/13088/chapter/2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) National healthcare disparities report. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; 2014. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bittoni MA, Wexler R, Spees CK, et al. Lack of private health insurance is associated with higher mortality from cancer and other chronic diseases, poor diet quality, and inflammatory biomarkers in the United States. Prev Med. 2015 Dec;81:420–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.09.016. Epub 2015 Oct 9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.09.016 PMid:26453984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2015. Trends in health insurance and unmet medical need for persons under 65 years of age, in the United States and selected states from 2004-June 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/health_policy/StateTrendsinAccess04to10q1q2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayes SL, Riley P, Radley DC. Closing the gap: past performance of health insurance in reducing racial and ethnic disparities in access to care could be an indication of future results. Washington, DC: The Commonwealth Fund; 2015. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/files/publications/issue-brief/2015/mar/1805_hayes_closing_the_gap_reducing_access_disparities_ib_v2.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peterson LE, Litaker DG. County-level poverty is equally associated with unmet health care needs in rural and urban settings. J Rural Health. 2010 Fall;26(4):373–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00309.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00309.x PMid:21029173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirby JB, Kaneda T. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and access to health care. J Health Soc Behav. 2005 Mar;46(1):15–31. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600103. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650504600103 PMid:15869118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirby JB, Kaneda T. Access to health care: does neighborhood residential instability matter? J Health Soc Behav. 2006 Jun;47(2):142–55. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700204. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650604700204 PMid:16821508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahern MM, Hendryx MS. Community characteristics as predictors of perceived HMO quality. Health Place. 1998 Jun;4(2):151–60. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(98)00007-0. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1353-8292(98)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendryx MS, Ahern MM, Lovrich NP, et al. Access to health care and community social capital. Health Serv Res. 2002 Feb;37(1):87–103. PMid:11949928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pagán JA, Pauly MV. Community-level uninsurance and the unmet medical needs of insured and uninsured adults. Health Serv Res. 2006 Jun;41(3 Pt 1):788–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00506.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00506.x PMid:16704512 PMCid:PMC1713201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahern MM, Hendryx MS. Social capital and trust in providers. Soc Sci Med. 2003 Oct;57(7):1195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00494-x. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00494-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Traveling towards disease: transportation barriers to health care access. J Community Health. 2013 Oct;38(5):976–93. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9681-1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-013-9681-1 PMid:23543372 PMCid:PMC4265215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arcury TA, Preisser JS, Gesler WM, et al. Access to transportation and health care utilization in a rural region. J Rural Health. 2005 Winter;21(1):31–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00059.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00059.x PMid:15667007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace R, Hughes-Cromwick P, Mull H, et al. Access to health care and nonemergency medical transportation: two missing links. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transporation Research Board; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rask KJ, Williams MV, Parker RM, et al. Obstacles predicting lack of a regular provider and delays in seeking care for patients at an urban public hospital. JAMA. 1994 Jun 22–29;271(24):1931–3. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.271.24.1931 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1994.03510480055034 PMid:8201737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silver D, Blustein J, Weitzman BC. Transportation to clinic: findings from a pilot clinic-based survey of low-income suburbanites. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012 Apr;14(2):350–5. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9410-0. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-010-9410-0 PMid:22512007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pheley AM. Mass transit strike effects on access to medical care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1999 Nov;10(4):389–96. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0677. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2010.0677 PMid:10581883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Transportation Statistics Annual Report 2013. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation; 2014. Available at: https://www.rita.dot.gov/bts/sites/rita.dot.gov.bts/files/TSAR_2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tierney WM, Harris LE, Gaskins DL, et al. Restricting Medicaid payments for transportation: effects on inner-city patients’ health care. Am J Med Sci. 2000 May;319(5):326–33. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200005000-00010. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9629(15)40760-8 https://doi.org/10.1097/00000441-200005000-00010 PMid:10830557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J, Norton EC, Stearns SC. Transportation brokerage services and Medicaid beneficiaries’ access to care. Health Serv Res. 2009 Feb;44(1):145–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00907.x. Epub 2008 Sep 17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00907.x PMid:18823447 PMCid:PMC2669622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper HL, Hunter-Jones J, Kelley ME, et al. The aftermath of public housing relocations: relationships between changes in local socioeconomic conditions and depressive symptoms in a cohort of adult relocaters. J Urban Health. 2014 Apr;91(2):223–41. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9844-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-013-9844-5 PMid:24311024 PMCid:PMC3978147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popkin SJ, Levy DK, Harris LE, et al. HOPE VI panel study: baseline report. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2002. Available at: http://webarchive.urban.org/UploadedPDF/410590_HOPEVI_PanelStudy.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oakley D, Ruel E, Reid L. “It was really hard.… It was alright.… It was easy” Public housing relocation experiences and destination satisfaction in Atlanta. Cityscape. 2013;15(2):173–92. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruel E, Oakley D, Wilson GE, et al. Is public housing the cause of poor health or a safety net for the unhealthy poor? J Urban Health. 2010 Sep;87(5):827–38. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9484-y. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-010-9484-y PMid:20585883 PMCid:PMC2937128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keene DE, Geronimus AT. “Weathering” HOPE VI: the importance of evaluating the population health impact of public housing demolition and displacement. J Urban Health. 2011 Jun;88(3):417–35. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9582-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-011-9582-5 PMid:21607787 PMCid:PMC3126923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmed AT, Mohammed SA, Williams DR. Racial discrimination & health: pathways & evidence. Indian J Med Res. 2007 Oct;126(4):318–27. PMid:18032807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009 Feb;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. Epub 2008 Nov 22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0 PMid:19030981 PMCid:PMC2821669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Racism and health I: pathways and scientific evidence. Am Behav Sci. 2013 Aug 1;57(8) doi: 10.1177/0002764213487340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213487340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keene DE, Padilla MB. Race, class and the stigma of place: moving to “opportunity” in Eastern Iowa. Health Place. 2010 Nov;16(6):1216–23. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.08.006. Epub 2010 Aug 10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.08.006 PMid:20800532 PMCid:PMC2964645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper HL, Bonney LE, Ross Z, et al. The aftermath of public housing relocation: relationship to substance misuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013 Nov 1;133(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.06.003. Epub 2013 Jul 10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.06.003 PMid:23850372 PMCid:PMC3786035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper HL, Linton S, Haley DF, et al. Changes in exposure to neighborhood characteristics are associated with sexual network characteristics in a cohort of adults relocating from public housing. AIDS Behav. 2015 Jun;19(6):1016–30. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0883-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0883-z PMid:25150728 PMCid:PMC4339671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper HL, Haley DF, Linton S, et al. Impact of public housing relocations: are changes in neighborhood conditions related to STIs among relocaters? Sex Transm Dis. 2014 Oct;41(10):573–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000172. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000172 PMid:25211249 PMCid:PMC4163933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fauth RC, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Short-term effects of moving from public housing in poor to middle-class neighborhoods on low-income, minority adults’ outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 2004 Dec;59(11):2271–84. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.020 PMid:15450703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fauth RC, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Seven years later: effects of a neighborhood mobility program on poor Black and Latino adults’ well-being. J Health Soc Behav. 2008 Jun;49(2):119–30. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900201. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650804900201 PMid:18649497 PMCid:PMC3117324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cummings J, Ko M, Allen L, et al. Public housing relocations and changes in access to health care. Boston, MA: American Public Health Association, Academy Health Annual Meeting Disparities Interest Group; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper HL, Wodarski S, Cummings J, et al. Public housing relocations in Atlanta, Georgia, and declines in spatial access to safety net primary care. Health Place. 2012 Nov;18(6):1255–60. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.08.007. Epub 2012 Sep 8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.08.007 PMid:23060002 PMCid:PMC3501556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andrews JO, Mueller M, Newman SD, et al. The association of individual and neighborhood social cohesion, stressors, and crime on smoking status among African-American women in southeastern US subsidized housing neighborhoods. J Urban Health. 2014 Dec;91(6):1158–74. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9911-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-014-9911-6 PMid:25316192 PMCid:PMC4242849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pollack CE, Green HD, Kennedy DP, et al. The impact of public housing on social networks: a natural experiment. Am J Public Health. 2014 Sep;104(9):1642–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301949. Epub 2014 Jul 17. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.301949 PMid:25033153 PMCid:PMC4151944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.James CV, Salganicoff A, Thomas M, et al. Putting women’s health care disparities on the map: examining racial and ethnic disparities at the state level. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2009. Available at: http://kff.org/disparities-policy/report/putting-womens-health-care-disparities-on-the/ [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000 Feb;34(6):1273–302. PMid:10654830 PMCid:PMC1089079. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doran KM, Shumway M, Hoff RA, et al. Correlates of hospital use in homeless and unstably housed women: the role of physical health and pain. Womens Health Issues. 2014 Sep-Oct;24(5):535–41. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.06.003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2014.06.003 PMid:25213745 PMCid:PMC4163010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gelberg L, Robertson MJ, Arangua L, et al. Prevalence, distribution, and correlates of hepatitis C virus infection among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Public Health Rep. 2012 Jul-Aug;127(4):407–21. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700409. PMid:22753984 PMCid:PMC3366378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stein JA, Andersen R, Gelberg L. Applying the Gelberg-Andersen behavioral model for vulnerable populations to health services utilization in homeless women. J Health Psychol. 2007 Sep;12(5):791–804. doi: 10.1177/1359105307080612. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105307080612 PMid:17855463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stein JA, Andersen RM, Robertson M, et al. Impact of hepatitis B and C infection on health services utilization in homeless adults: a test of the Gelberg-Andersen Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations. Health Psychol. 2012 Jan;31(1):20–30. doi: 10.1037/a0023643. Epub 2011 May 16. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023643 PMid:21574705 PMCid:PMC3235541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berk ML, Schur CL, Cantor JC. Ability to obtain health care: recent estimates from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation National Access to Care Survey. Health Aff (Millwood) 1995 Fall;14(3):139–46. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.3.139. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.14.3.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Logan JR, Xu Z, Stults BJ. Longitudinal Tract Data Base. Providence, RI: Spatial Strucures in the Social Sciences, Brown University; 2012. Available at: https://s4.ad.brown.edu/projects/diversity/Researcher/Bridging.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oliver ML, Shapiro TM. Black wealth/White wealth: a new perspective on racial inequality. 2. New York, NY: Routledge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peters RH, Greenbaum PE, Steinberg ML, et al. Effectiveness of screening instruments in detecting substance use disorders among prisoners. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000 Jun;18(4):349–58. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00081-1. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-5472(99)00081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997 Aug 15;277(5328):918–24. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.277.5328.918 PMid:9252316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barrera M, Jr, Ainlay SL. The structure of social support: a conceptual and empirical analysis. J Community Psychol. 1983 Apr;11(2):133–43. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(198304)11:2<133::aid-jcop2290110207>3.0.co;2-l. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(198304)11:2<133::AID-JCOP2290110207>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, et al. Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med. 2005 Oct;61(7):1576–96. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. Epub 2005 Apr 21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006 PMid:16005789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996 Mar;34(3):220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 PMid:8628042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ruel E, Oakley DA, Ward C, et al. Public housing relocations in Atlanta: documenting residents’ attitudes, concerns and experiences. Cities. 2013;35:349–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.07.010. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fujii T, Hartshorni TA. The changing metropolitan structure of Atlanta, Georgia: locations of functions and regional structure in a multinucleated urban area. Urban Geogr. 1995;16(8):680–707. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.16.8.680. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malmgren JA, Martin ML, Nicola RM. Health care access of poverty-level older adults in subsidized public housing. Public Health Rep. 1996;111(3):260–3. PMid:8643819 PMCid:PMC1381770. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bonney LE, Cooper HL, Caliendo AM, et al. Access to health services and sexually transmitted infections in a cohort of relocating African American public housing residents: an association between travel time and infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2012 Feb;39(2):116–21. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318235b673. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318235b673 PMid:22249300 PMCid:PMC3261426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 1997;44(2):174–99. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.1997.44.2.03x0221m https://doi.org/10.2307/3096941. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Watters JK, Biernacki P. Targeted sampling: options for the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 1989;36(4):416–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/800824 https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.1989.36.4.03a00070. [Google Scholar]

- 61.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. The Georgia health care landscape. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2014. Available at: http://kff.org/health-reform/fact-sheet/the-georgia-health-care-landscape/ [Google Scholar]