Abstract

HIV affects over 1.2 million people in the United States; a substantial number are men who have sex with men (MSM). Despite an abundance of literature evaluating numerous social/structural and individual risk factors associated with HIV for this population, relatively little is known regarding the individual-level role of masculinity in community-level HIV transmission risk. To address this gap, the current analysis systematically reviewed the masculinity and HIV literature for MSM. The findings of 31 sources were included. Seven themes were identified: 1) Number of partners, 2) Attitudes toward condoms, 3) Drug use, 4) Sexual positioning, 5) Condom decision-making, 6) Attitudes toward testing, and 7) Treatment compliance. These factors, representing the enactment of masculine norms, potentiate the spread of HIV. The current article aligns these factors into a Masculinity Model of Community HIV Transmission. Opportunities for counseling interventions include identifying how masculinity informs a client’s cognitions, emotions, and behaviors as well as adapting gender transformative interventions to help create new conceptualizations of masculinity for MSM clients. This approach could reduce community-level HIV incidence.

Keywords: Masculinity, HIV, intervention, MSM, transmission, gender-transformative

INTRODUCTION

There are approximately 1.2 million people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in the United States. There are roughly 50,000 new HIV infections every year. Though constituting less than 5% of the US male population, men who have sex with men (MSM) account for half of PLWHA. Latino and Black MSM have nearly three times and seven times the HIV incidence of White MSM respectively. MSM of all ethnic groups are the only population with significant increases in new HIV diagnoses (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010, 2011; Prejean, Song, An, & Hall, 2009; US Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2013).

The transmission of HIV between MSM has been the focus of a sizable body of literature. This research has indicated that HIV transmission is a function of two concurrent and interactive influences: 1) Social/Structural Factors and 2) Individual Factors (Poundstone, Strathdee, & Celentano, 2004; Remien & Mellins, 2007). The social/structural factors significantly related to HIV transmission include poverty, political policy, education, social norms, homelessness, stigma, social capital, and racial segregation (Latkin, German, Vlahov, & Galea, 2013; Molina, & Ramirez-Valles, 2013; Poundstone et al., 2004; Zeglin & Stein, 2014). These factors are considered to explain the disproportionate incidence among minority racial groups, as there is evidence that individual-level factors alone do not indicate increased risk among these populations (Friedman, Cooper, & Osborne, 2009; Millett, Flores, Peterson, & Bakeman, 2007). Structural interventions addressing these factors have been propagated in the HIV epidemiology literature. These include housing programs, increased access to health-care, better education, community empowerment, and improved transportation systems (Adimora & Auerbach, 2010; Cohen, 2012; Kegeles, Hays, & Coates, 1996; Prado, Lightfoot, & Brown, 2013).

There has also been a proliferation of theories and models examining HIV risk behavior of individuals (Noar, 2007). These models were informed by research identifying various individual-level risk factors including internalized homonegativity (Ross, Rosser, & Neumaier, 2008), sexual desire (Zea, Reisen, Poppen, & Bianchi, 2009), condom self-efficacy (Newcomb & Mustanski, 2013; Widman, Golin, Grodensky, & Suchindran, 2013), drug use (Mustanski, 2008; Mutchler et al., 2011), perceived social norms (Peterson, Rothenberg, Kraft, Beeker, & Trotter, 2009), sensation seeking (Newcomb, Clerkin, & Mustanski, 2011) and psychosocial stress (Deuba et al., 2013; Safren, Blashill, & O’Cleirigh, 2011). There are currently seven individual-level HIV risk reduction interventions for MSM identified by CDC (2013a) as good or best practices.

The current analysis contends that masculinity is also a mechanism of HIV transmission among MSM at the community-level, one that has been under-researched in the HIV/AIDS epidemiologic literature. Masculinity is a socially constructed concept but is individually enacted (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Mahalik et al., 2003; Scruton, 2001; Shively & de Cecco, 1977, 1993). The construct remains difficult to define, particularly in research, but is generally considered the typical enactment of behaviors, beliefs, values, feelings, and cognitions of male identity (e.g., Hergenrather, Zeglin, Ruda, Hoare, & Rhodes, 2014; Knight et al., 2012; Mahalik et al., 2003; Rothgerber, 2013; Seibert, & Gruenfeld, 1992; Wester & Vogel, 2012; Woodhill & Samuels, 2004). Mahalik (2014) noted that the study of masculinity is “conceptually and methodologically disjointed” (p. 367), thus creating a “sticky” understanding of masculinity (Berggren, 2014).

To ease in the investigation of masculinity, many validated scales have been created to measure this challenging construct. Mahalik et al. (2003), in a series of studies, developed and validated the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory (CMNI). The CMNI is a 132-item inventory that assesses an individual’s self-rated conformity to 11 psychometrically sound scales (e.g., Power of women, Dominance, Winning, Playboy). Similarly, the Male Role Norms Inventory (MRNI; Levant et al., 2007) assesses one’s level of masculine ideology, using 57 items, along eight scales (e.g., Hatred of homosexuals; Non-relational attitudes towards sexuality, Restrictive emotionality). Some scales have also been developed to assess an individual’s gender role strain (i.e., the distress resulting from challenges in meeting masculine ideals and/or in experiencing negative outcomes because of meeting them). The Gender Role Conflict Scale (GRCS), for exmaple, was devleoped by O’Neil, Helms, Gable, David, and Wrightsman (1986). This 37-item assessment measures the degree to which an individual reports negative consequences of navigating rigid gender norms. All of these scales share a common theme; they call attention to a need for a clearer understanding of masculine norms.

Hegermonic masculinity is broadly described as the configuration of dominant masucline norms that maginalize and suborinate women and other men (Connell, 1995; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). Discussion of hegemonic masculinity typically includes traits such as ambition, risk-taking, strength, success, heterosexuality, sexual adventurism, leadership, muscular physical features, and stoicism. Few men are able to achive this idealized form of masculinity, resulting in gender role strain. To compensate, some men enact hypermasculinity (i.e., engaging in amplified masculine norms including sexual promiscuity, body-building, and denying weakness or pain; Connell, 1995; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Eguchi, 2009; Reeser, 2010). This can have very real health consequences for men. For example, there are strong associations between masculinity and reduced help-seeking behaviors (Galdas, Cheater, & Marshall, 2005; O’brien, Hunt, & Hart, 2005). As Courtenay (2000) succinctly states, “To carry out any one positive health behaviour, a man may need to reject multiple constructions of masculinity” (p. 1389). Aligning with this, research has shown that men who are more conforming to masculine norms are significantly less likely to engage in positive health behaviors (Mahalik, Burns, & Syzdek, 2007) and are significantly more likely to endorse mental health symptoms (Mahalik et al., 2003). This relationship between masculinity and health behavior highlights the possible significance of investigating the role of masculinity in HIV-related health behaviors (e.g., condom use, testing, medication adherence).

Some suborinated masculinities, including that of MSM, cannot ipso facto achieve hegemonic masuclinity, therefore creating significant gender role strain and even further supporting the enactment of hypermasculinity (Eguchi, 2009; Fields et al., 2015). Further, masculine norms are influcned by the intersecting identities of race, sexual orientation, and masculinity. Racial/ethnic minority men face sociopolitical challenges to obtaining many hegemonic masculine norms (e.g., education, employment). This can result in significant gender role strain, motivating these men to, in turn, demonstrate masculine identity through other means (e.g., physical toughness or sexual prowess). For racial/ethinic minority MSM, these alternatives still do not alter sexual orientation, heterosexuality being a staple of hegemonic masculinity. This is thought to be responsible for the “down low” phenomenon in the black MSM community (Bowleg, 2013; Bowleg et al., 2011; Fields et al., 2012, 2015; Ford, Whetten, Hall, Kaufman, & Thrasher, 2006; Malebranche, 2003, 2008; Malebranche et al., 2009; Saez, Casado, & Wade, 2009). Non-heterosexuality remains an immutable barrier to hegemonic masculinity.

Though achieving hegeminic masculinity may be impossible, hegemonic masculine norms remain the only guidepost by which MSM can assess their behaviors and practices (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Demetriou, 2001; Fields et al., 2015), making masculinity a viable target of inquiry to better understand MSM’s behaviors. For exmaple, the influence of hegemonic masculinity plays a part in shaping the gay male body. The idealization of muscularity, size, and stamina within gay masculinities is a reification of hegemonic masculinity through hypermasculinity (Demetriou, 2001; Reeser, 2010). In fact, as Hennen (2005) suggests, this fit muscular physique can serve to subjugate the feminizing features of other body shapes within the gay community, affecting an intra-community hegemony. Halkitis (2001) and Halkitis, Green, and Wilton (2004) found that, for MSM living with HIV, maintaining a strong physical presence was a salient concern and noted that this was connected to an overall sense of virility. Tate and George (2001) revealed a poignant relationship between HIV and body image among MSM, with many participants feeling that HIV undermined their control of their body and negatively affected their social presence, challenging their ability to enact idealized physical masculinity.

Some researchers have used the link between HIV and masculinity to explore how the latter may be a risk factor for HIV/AIDS. Men may be vunerable to HIV infection because of their concpeutalization of and attempts at enacting masculinity (Barker & Ricardo, 2005; Gupta, 2000; Morrell, 2003). Enacting hegemonic masucline norms puts men at risk for HIV via reluctance to get tested, having multiple sexual partners, and having risky sexual encounters, highlighting a relevant place for men and their masculinity as agents of HIV prevention (Dworkin, Fullilove, & Peacock, 2009; Dworkin, Treves-Kagan, & Lippman, 2013; Higgins, Hoffman, & Dworkin, 2010; Verma et al., 2006). Malebranche, Gvetadze, Millett, and Sutton (2012) found that greater gender role strain among men was associated with an increased likelihood of unprotected sex with their female partners. Additionally, Bowleg et al. (2011) found, among a sample of black men, that the expectations surrounding masculinity do not permit them to ever decline sex. The bulk of this work has been done with heterosexual males and often outside of the United States. The only CDC (2013a) good or best practice to explicitly mention masculinity as a component of its intervention strategy, HoMBREeS (Rhodes, Hergenrather, Bloom, Leichliter, & Montaño, 2009), is targeted for heterosexual Latino males.

Though much of the literature investigating masculinity and HIV/AIDS risk has been done with heterosexual men, there is increasing awareness of this dynamic in the lives of MSM. Work being done by Fields and colleagues (2012; 2015), Malebranche (2008), and Malebranche et al. (2009) has consistently identified a significant relationship between the navigation of masculinity and HIV/AIDS risk. Their work has shown that, among black MSM, enactments of culturally accepted masculine norms is linked to increased HIV risk behavior including unprotected sex, partner concurrency, and negative attitudes toward gay communities and resources. In fact, Fields et al. (2012) found that participants reported using perceived masculinity to assess HIV status in partners.

Fields et al. (2015), perhaps in particular, demonstrated that black MSM accredited some of their HIV risk behavior to the effects of gender role strain. This supports the notion that the psychological processes and consequences of navigating masculinity can influence HIV risk behavior. Although most of the seven CDC (2013a) individual-level HIV risk reduction interventions for MSM are to be delivered in counseling, none directly address the construct of masculinity. The present analysis contends that, since masculinity is individually enacted, it is a viable target for counseling interventions which can then have an impact on reducing community-level HIV transmissions.

Fields et al. (2012; 2015) and Mays, Cochran, and Zamudio (2004) called for the inclusion of masculinity in HIV prevention strategies for MSM. The current analysis seeks to begin to answer this call by first establishing a model from which to conceptualize the role of masculinity in the spread of HIV at the community level, inspired by the aforementioned work being done with MSM at the individual level. By doing so, masculinity may be revealed as a bridge between the individual-level and social/structural-level factors discussed in Poundstone et al. (2007), and masculinity-focused counseling interventions may be one vehicle to cross that bridge. Counseling professionals (e.g., therapists, social workers, nurses) work with at-risk MSM before and after HIV seroconversion (i.e., becoming infected with HIV). By better understanding the role of masculinity in HIV transmission, they can begin to offer more holistic and culturally sensitive HIV risk reduction interventions. Halkitis et al. (2004) noted that it is important to understand how the navigation of masculinity for MSM has “an impact on the decisions these men make and the behaviors in which these men engage” (p. 40). To this end, the objective of this article is to support this understanding by: 1) presenting a review of relevant sources; 2) synthesizing the information into a masculinity model of community HIV transmission; and 3) identifying opportunities for masculinity-based counseling interventions with MSM.

METHOD

Theoretical Framework

Masculinity was the variable being explored. Because masculinity remains relatively undefined, and considering its inconsistent appearance in community-level HIV infection literature among MSM, the present analysis utilized a post-positivist methodological epistemology to conceptualize masculinity (Creswell 2007, 2013; Hergenrather et al., 2014; Martin, 1998; Spence & Buckner, 1995). This approach asserts that, although masculinity maintains a true quality, it can only be ascertained by examining its smaller, less accurate, and more imperfect parts. This creates a methodlogical pluralism wherein the variable of interest is allowed to vary across included sources. This may be particuallry important when investigating constructs that are still ill-defined, in flux, or for those whose definitions are still contested (Creswell, 2007, 2013; Mahalik, 2014). Masclunity among MSM, as discussed above, was felt to be reliably within this category. As such, the current analysis did not hold the definition of masculinity constant across sources, allowing the articles instead to present the largest possible picture of masculinity’s role in community HIV transmission. Operatonally, this means that sources were included regardless of their definition of masculinity (e.g., masculine norms, masculine idiology, gender role) or of their measure of masculinity.

Review Process

The literature review included a keyword search of online databases. The databases used were Google Scholar, ProQuest, PsychINFO, PubMed, and ScienceDirect and were searched from their inception through 2013. The keywords included: masculinity, masculine norms, HIV, MSM, men who have sex with men, gay men, homosexual, risk factors, and protective factors. Inclusion criteria were: 1) available in English 2) peer-reviewed articles; 3) books or book chapters; and 4) having sufficient discussion of results or themes for proper data abstraction.

The initial search yielded over 1,500 sources. Titles and abstracts not fitting within the scope of the review were immediately omitted, leaving 53 sources for review. Of these, 31 did not meet inclusion criteria and were removed, leaving 22 sources. A bibliography review yielded nine additional sources. Ultimately, the literature search identified 31 sources examining the relationship between masculinity and HIV transmission for MSM.

The author utilized a four-step review process to identify the salient themes in the literature. First, data from each source were abstracted using an instrument to document key features of each source. These included independent variable(s), dependent variable(s), and (depending on the type of source) statistically significant results, qualitatively identified themes, and/or applicable discussions with adequate research support. Then, the author reviewed the data abstraction instrument to qualitatively categorize the sources’ findings. Seven salient themes were identified. The author then, in the third step, used the list of seven themes to crosscheck all findings in the data abstraction instrument. Finally, an independent reviewer who is a professional in the field of HIV prevention assessed the final list of seven themes and considered them face valid with respect to masculinity and community HIV transmission risk.

RESULTS

Seven themes were identified: 1) number of partners, 2) attitudes toward condoms, 3) drug use, 4) sexual positioning, 5) condom decision-making, 6) attitudes toward testing, and 7) treatment compliance. Each theme is significantly associated with increased risk for community-level HIV transmission and is therefore considered a risk factor. The present analysis identified zero community-level protective factors associated with masculinity in the literature, though occasional non-significant findings were reported and are included where appropriate.

Pre-Exposure

Pre-exposure factors are conceptualized as those that are present before and/or that facilitate seroconversion. These factors are further divided into two sub-groups. General risk factors are those that potentiate risky sexual encounters and include a) number of partners; b) attitudes toward condoms; and c) drug use. Intradyadic risk factors are those that are salient in the course of a particular sexual encounter and include a) condom decision-making; and b) sexual positioning. The distinction between general and intradyadic factors is highlighted in Zea et al., (2009).

Number of partners

Demonstrations of sexual prowess through high partner concurrency has been identified as a masculine behavior (Halkitis et al., 2004; Malebranche et al., 2009; Sánchez, Greenberg, Liu, & Vilain, 2009). Halkitis (2001) notes that masculinity for MSM is “often associated with both the frequency of the sexual behaviors as well as the adventurism associated with sexual encounters” (p. 420). Parent, Torrey, & Michaels (2012) found that, among 170 MSM, number of sexual partners was positively correlated to masculinity. In a longitudinal study of over 4,000 MSM, Koblin et al. (2006) reported that high numbers of sexual partners was positively associated with HIV infection. CDC (2013b), The National AIDS Trust (NAT; 2010), and USDHHS (2013) identify multiple partners and partner concurrency as an HIV risk factor.

Attitudes toward condoms

Shernoff (2006) and Halkitis (2001) detail the dynamic influences on MSM’s negative attitudes toward condom use, citing masculinity as a possible factor. In a detailed literature review, Berg (2009) presented masculinity as a factor associated with identifying as a “barebacker” (i.e., not using condoms during sex). This has been consistently demonstrated, as MSM report that not using condoms is more masculine (Dowsett, Williams, Ventuneac, & Carballo-Diéguez, 2008; Halkitis & Parsons, 2003; Halkitis, Parsons, & Wilton, 2003; Ridge, 2004). Hamilton & Mahalik (2009) found that masculinity was correlated to frequency of unprotected sex and to the belief that unprotected sex was normative. Notably, Malebranche et al. (2009) did not find this association in their sample of MSM. Unprotected anal sex is a substantial risk factor for HIV (CDC, 2013b; Koblin et al., 2006; NAT, 2010; USDHHS, 2013).

Drug use

Masculinity has been associated with drug use in the MSM community (Halkitis, 1999). Shernoff (2006) discussed drugs’ role in gay culture, highlighting the connection between substance use and sex. Halkitis et al. (2008b) reported a similar theme, finding that MSM who reported higher rates of drug use were more likely to conceptualize masculinity in sexual terms. The study also found that nearly 25% of the MSM they sampled reported methamphetamine (meth) use. Masculinity is also associated with steroid and alcohol use among MSM (Halkitis, Moeller, & DeRaleau, 2008a; Hamilton & Mahalik, 2009). MSM who self-identified as “barebackers” (an identity associated with masculinity) were more likely to report both injection and non-injection drug use (Halkitis et al., 2005). However, Hamilton & Mahalik (2009) did not find a correlation between masculinity and drug use. Koblin et al. (2006) found that 29% of HIV infections in their sample were attributable to alcohol or drug use prior to sex.

Sexual positioning

Literature indicated that masculinity was also related to sexual positioning within a dyad (i.e., whether the person is insertive [top] or receptive [bottom]; Carballo-Diéguez et al., 2004; Fields et al., 2012; Jarama, Kennamer, Poppen, Hendricks, & Bradford, 2005; Johns, Pingel, Eisenberg, Santana, & Bauermeister, 2012; Malebranche et al., 2009). In a sample of 1,065 MSM, men with above average penises (a social proxy for masculinity) were more likely to identify as tops (Grov, Parsons, & Bimbi, 2010). Moskowitz and Hart (2011), in their sample of 429 MSM, found that masculinity and penis size were significant predictors of sexual position. Zheng, Hart, and Zheng, (2012) found that, among 220 MSM, self-identified tops had significantly higher masculinity scores than self-identified bottoms and men identifying as versatile. Conversely, some interviews presented in Ridge (2004), suggest that positioning as a bottom is perceived as the more masculine role. Zheng, Hart, and Zheng, (2013) found that self-identified tops preferred men with feminine facial features, particularly if the participant was less restricted in their sociosexual orientation (i.e., accepting brief sexual relationships). Similarly, they found that self-identified bottoms preferred men with masculine facial features, particularly for less sociosexually restricted participants. MSM identifying as bottoms are over twice as likely as others to be HIV-positive (Wei & Raymond, 2011).

Condom decision-making

Within a dyad, there is reference to the more masculine partner making the condom-use decision (Fields et al., 2012). The decision-making power is deferred in this way because masculine partners are considered safe partners (Fields et al., 2012; Kippax & Smith, 2001; Malebranche et al., 2009; Shernoff, 2006). This dynamic is confounded by the fact that penis size is positively correlated to difficulty finding appropriately fitting condoms, frequency of condom breakage and slippage, and contraction of sexually transmitted infections (STIs; Grov et al., 2010; Gov, Wells, & Parsons, 2013). Nearly 20% of MSM report condom malfunction, increasing STI risk (CDC, 2013b; D’Anna et al., 2012; USDHHS, 2013).

Post-Exposure

Post-exposure factors are conceptualized as those present after potential seroconversion. These risk factors include a) attitudes toward testing and b) treatment compliance. Both of these factors are general risk factors; no post-exposure intradyadic factors were identified.

Attitudes toward testing

Masculinity has been associated with a reluctance to seek help. Parent et al. (2012), in their article titled “‘HIV Testing is so Gay’,” noted that the masculine norm of preserving a heterosexual presentation predicted lower HIV testing. This is congruent with research indicating that a common barrier to testing is perceived homophobia (Santos et al., 2013; Scott et al., 2013; Sullivan et al., 2012). Infrequent testing is a considerable risk factor for the transmission of HIV (CDC, 2013b; NAT, 2010; USDHHS, 2013). Literature suggests that men who receive testing and are HIV-positive are less likely to have unprotected anal intercourse with HIV-negative or HIV-unknown men (Poppen, Reisen, Zea, Bianchi, & Echeverry, 2005; Zablotska et al., 2009).

Treatment compliance

There is an association between masculinity and medication non-adherence among HIV+ men (Nieves-Lugo & Toro-Alfonso, 2012). Blashill and Vander Wal (2010) noted that the pressure to appear in shape and to project physical masculinity could facilitate HAART non-compliance. Galvan, Bogart, Wagner, and Klein (2012) found that, among 208 HIV+ Latino MSM, men endorsing traditional machismo (i.e., a cultural conceptualization of masculinity) were half as likely as others to report 100% adherence to medication. The side effects of HIV medication can reduce libido, virility, and erectile tumescence; these are perceived threats to masculinity and could be barriers to adherence (Halkitis, 2001). Non-adherence to antiretroviral medication increases viral load, leading to higher infectivity (CDC, 2013b; USDHHS, 2013; Dieffenbach & Fauci, 2009; Kalichman et al., 2011).

DISCUSSION

Masculinity Model of Community HIV Transmission

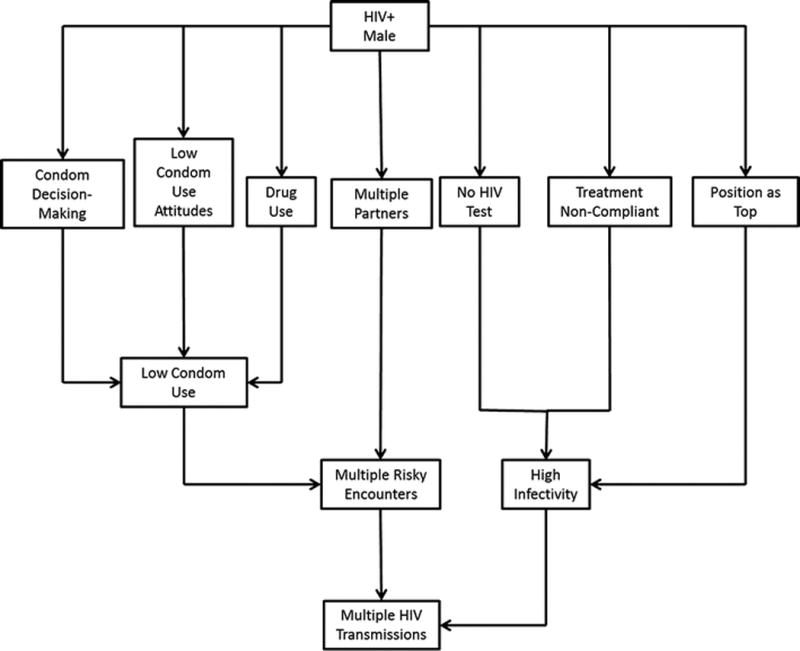

The present review suggests that, taken together, the identified factors produce a Masculinity Model of Community HIV Transmission (MMCHT). This model (see Figure 1) demonstrates how masculinity can be one factor responsible for the rapid proliferation of HIV within the MSM community. The seven risk factors culminate in three intermediary risk scenarios; the confluence of these ultimately leads to multiple community HIV transmissions.

Figure 1.

Masculinity Model of Community HIV Transmission. This figure outlines the process by which the enactment of masculine norms can facilitate rapid community-level HIV transmission.

Low condom use

Figure one demonstrates how three of the MMCHT risk factors may lead to low condom use. The model suggests that men who enact these masculine norms not only have poor attitudes toward condoms but are also the ones ultimately making the decision whether condoms will be used during a particular sexual encounter. Individuals with negative attitudes toward a behavior that they also feel in control of are unlikely to engage in that behavior (Ajzen, 2012; Conner & McMillan, 1999). Moreover, the MMCHT notes that this decision-making process may be clouded by drug use prior to the sexual encounter. The confluence of these factors is a decreased chance that condoms will be used during a particular sexual encounter, qualifying such an encounter as a risk for possible transmission.

Multiple risky encounters

The MMCHT also notes the influence of the masculine norm of multiple partners and partner concurrency. As such, the risk of community-level transmission is a function of the risk present within a single risky encounter (see above) being multiplied several times over by having multiple partners and partner concurrency. As the number of sexual partners increases, the number of possible community transmissions increases correspondingly.

Increased infectivity

Finally, the model outlines how masculine attitudes toward testing, treatment, and sexual positioning increase the infectivity of a male who conforms to these normative attitudes. Even within an unprotected sexual encounter, the risk of transmission is relatively low if the infected partner has been tested, is adherent to treatment, and is the receptive partner (Beyrer et al., 2012; Granich, Gilks, Dye, De Cock, & Williams, 2009). Otherwise, infectivity is high. If this increased infectivity is present across the multiple risky encounters mentioned above, there is a significant risk of multiple rapid community-level HIV transmissions.

Individual Risk vs. Community Risk

It is important to note that some of the aforementioned factors may be protective for an individual while also increasing the risk of community-level transmission, aligning with the MMCHT. For example, sexual position as a top is protective for an individual within a particular sexual dyad. However, if a top rather than a bottom is HIV+ there is a heightened community-level risk of transmission due to the increased infectivity of the insertive partner to the receptive partner. As discussed above and as displayed in Figure 1, this infectivity is amplified by several other masculine norms that may also be expressed by the individual (e.g., multiple partners). For this reason, the seven identified risk factors are contributors to the MMCHT, regardless of their status as protective factors for an individual. The Masculinity Model of Community HIV Transmission indicates that masculinity is an important component to consider, among many others, within the social epidemiology of HIV.

Implications for Counseling Interventions

The treatment triangle, often utilized by counseling professionals, represents the interaction between an individual’s cognitions, emotions, and behaviors (Izard, Kagan, & Zajonc, 1985; Walen, DiGiuseppe, & Dryden, 1992). Theories of psychotherapy and counseling target at least one of these components in their conceptualization of distress and/or in their planning of interventions. Hergenrather et al. (2014) noted that the qualities traditionally associated with masculinity could be organized within the components of the treatment triangle. Counseling professionals, guided by CDC (2013a) good and best practices for HIV risk reduction, can begin to assess how a client conceptualizes masculinity within their culture and how this conceptualization informs each of these three components of the treatment triangle, paying particular attention to the seven themes from the Masculinity Model of Community HIV Transmission. This could include the use of standardized assessments (Mahalik, Talmadge, Locke, & Scott, 2005). Psychotherapy and counseling theories and interventions that are sensitive to the role of masculinity for the client and the client’s culture can then be selected and implemented (Addis & Cohane, 2005; Liu, 2005). Considering that masculinity is often a salient issue for MSM, this approach leads to more culturally competent and productive treatment (Dunn, 2012; Halkitis, 2001; Sánchez & Vilain, 2012; Sánchez, Westefeld, Liu, & Vilain, 2010). Because of the aforementioned myriad ways in which masculinity influences community HIV transmission risk, interventions targeting masculinity can have dynamic and widespread ameliorative effects.

Additionally, interventions that transform negative components of masculinity by highlighting the positive components could mitigate the catalytic influence of masculinity on community HIV transmission among MSM. Men who are presented with information demonstrating that traditional conceptualizations of masculinity may be harmful and who are provided support and safety in exploring alternative conceptualizations of masculinity are likely to reevaluate and alter their beliefs and behaviors relating to masculinity (Barker & Ricardo, 2005; Lynch, Brouard, & Visser, 2010). Gupta (2000) noted that these interventions conceptualize masculinity as a set of changeable social norms, seeking to create new behaviors that facilitate healthier lifestyles. These are described as gender-transformative interventions (Barker, Ricardo, Nascimento, Olukoya, & Santos, 2010; Dunkle & Jewkes, 2007; Dworkin et al., 2009; Gupta, 2000) and have been shown to have positive health-related results among heterosexual men, including reducing HIV risk behavior. Dworkin et al. (2013), in a review of literature from across the globe, detailed 15 gender-transformative interventions. They found that, in general, these interventions reduce sexual risk behaviors including unprotected sex, purchasing of sex, and concurrent partners.

For example, ‘Stepping Stones’ is a program encouraging discussions on the role of gender in community leadership, death, substance use, love and intimacy, sex, violence, and more (Welbourn, 2009). A systematic review of ‘Stepping Stone’ literature (Skevington, Sovetkina, & Gillison, 2013) found that the program increased HIV testing, increased condom use, reduced multiple partnering, and reduced substance abuse. Similar programs in Nicaragua, supported by USAID, report success reducing HIV transmission by highlighting prosocial self-esteem and self-care qualities of masculinity (Tallada, 2011). Farrimond (2012) noted that men who created a positive-focused model of masculinity perceived themselves as active and responsible participants in their healthcare. These men were more likely to seek medical help, going against traditional masculine norms. Additionally, Galvan et al. (2012), found that “caballerismo,” a culture-specific conceptualization of masculinity that stresses collaboration, family values, and respect, was significantly correlated to an increased likelihood of reporting 100% compliance with HIV medication. Many of these gender-transformative interventions were designed for heterosexual men in countries outside of the United States; the present analysis calls attention to the need for exploration of their effectiveness with MSM in the US as well.

Future Research

Although the current analysis identified several factors directly linking masculinity to HIV risk behavior, there are still opportunities for research to better clarify this relationship. Future inquiry can begin to uncover the ways in which masculinity is a component of other behaviors of interest, ones that may be less direct HIV risk factors. For example, masculinity has been included in research regarding disclosure of sexual orientation, HIV-status disclosure, community formation, and partner selection among MSM (Bianchi et al., 2010; Clark et al., 2013; García, Lechuga, & Zea, 2012; Knox, Reddy, Kaighobadi, Nel, & Sandfort, 2013). Though these studies offer inconsistent findings, they indicate a continued need to evaluate the role of masculinity in these and other constructs.

Similarly, as this analysis was a systematic literature review and not a meta-analysis, all sources were given equal weight in the discussion of their findings regardless of their limitations. Future studies should consider approaching the question of masculine ideology and community HIV transmission using a meta-analytic methodology. This may prove difficult at this juncture however, as there is still a paucity of quantitative studies investigating this issue with standardized and validated measures within the MSM population. Still, as more studies are conducted in this arena, there will be an opportunity to assess the true impact of masculine ideology on community HIV transmission, an impact that the current analysis suggests may not be insignificant.

Additionally, though the aforementioned gender-transformative approach to masculinity provides a proven foundation from which to start, it has not yet been widely applied to MSM populations. Its inclusion in the present article is a call for future examination of the theory’s applicability to this population. The efficacy and effectiveness of gender-transformative interventions for MSM should first begin with a rigorous evaluation of and possible revision to existing intervention curricula. Furthermore, it will be important to supplement these curricula with information that is particularly appropriate for masculinity-related topics within the MSM community. This should include participation by and input from MSM. Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) is a possible first step in this endeavor, prioritizing the role of MSM community members in the research process, data analysis, and dissemination of results (Rhodes, Malow, & Jolly, 2010). A CBPR approach also facilitates the creation of interventions that are sensitive to the intersections of race and class with masculinity (Hill, & McNeely, 2013; Rhodes, 2014; Rhodes et al., 2011). This line of inquiry can lead the way to evidence-based masculinity-focused interventions for MSM.

There is a sizable body of literature identifying the influential role of medical professionals in the lives of MSM (Hays, Turner, & Coates, 1992; Hergenrather, Rhodes, & Clark, 2005; Preau, 2004). Taylor and Robertson (1994) called for the nurses to become more familiar with the health care needs of MSM. Future research is needed to assess how medical professionals, particularly perhaps nurses, could employ the Masculinity Model of Community HIV Transmission during the course of their contact with patients. Doing so can lead to a collaborative interdisciplinary approach to reducing HIV transmission within a community.

Limitations

Evaluation of the concepts presented in this paper must be reviewed with due consideration of its limitations. First, based solely on a literature review, the model presented in Figure 1 requires quantitative validation, possibly through meta-analysis as mentioned above. This represents a necessary area of future study, particularly if subsequent interventions are to be explored. A second limitation is the measurement of masculinity. There is a paucity of studies validating common masculinity measures with MSM populations. As such, the conclusions drawn in the present article may be approximations. This is additionally confounded by the aggregation of masculinity across cultures. Masculinity and masculine norms can be expressed radically differently between, for example, racially diverse populations (Fields et al., 2012, 2015; Galvan et al., 2012; Hergenrather et al., 2014). Finally, this review is subject to the same publication bias inherent in any literature review. Though future empirical work can address these limitations, the present analysis achieved its objectives.

CONCLUSION

Masculinity is associated with seven risk factors for HIV transmission. These ultimately produce a complex masculinity model of community HIV transmission. From a social-epidemiologic perspective, masculinity seems to play an integral role in the spread of HIV within a community of MSM. Counseling professionals ought to explore masculinity with their clients, highlighting positive and prosocial components thereof. There is a clear need for developing interventions targeting masculinity among the MSM community, creating new prosocial conceptualizations of masculinity. This can empower MSM to enact masculinity in healthier ways, reducing HIV transmission risk. Positive results of such interventions could be advantageous for individual MSM and for the MSM community.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author received support from the District of Columbia Developmental Center for AIDS Research (P30AI087714).

References

- Addis ME, Cohane GH. Social scientific paradigms of masculinity and their implications for research and practice in men’s mental health. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61(6):633–647. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, Auerbach JD. Structural interventions for HIV prevention in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;55(Suppl 2):S132–S135. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fbcb38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. In: Van Lange PM, Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, editors. Handbook of theories of social psychology. Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Ltd.; 2012. pp. 438–459. [Google Scholar]

- Barker G, Ricardo C. Young men and the construction of masculinity in sub-Saharan Africa: implications for HIV/AIDS, conflict, and violence. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barker G, Ricardo C, Nascimento M, Olukoya A, Santos C. Questioning gender norms with men to improve health outcomes: Evidence of impact. Global Public Health. 2010;5(5):539–553. doi: 10.1080/17441690902942464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg RC. Barebacking: A review of the literature. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38(5):754–764. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berggren K. Sticky masculinity: Post-structuralism, phenomenology and subjectivity in critical studies on men. Men and Masculinities. 2014;17(3):231–252. doi: 10.1177/1097184X14539510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beyrer C, Baral SD, van Griensven F, Goodreau SM, Chariyalertsak S, Wirtz AL, Brookmeyer R. Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. The Lancet. 2012;380(9839):367–377. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi FT, Shedlin MG, Brooks KD, Penha MM, Reisen CA, Zea MC, Poppen PJ. Partner selection among Latino immigrant men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39(6):1321–1330. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9510-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashill AJ, Vander Wal J. The role of body image dissatisfaction and depression on HAART adherence in HIV positive men: Tests of mediation models. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(2):280–288. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9630-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. “Once you’ve blended the cake, you can’t take the parts back to the main ingredients”: Black gay and bisexual men’s descriptions and experiences of intersectionality. Sex Roles. 2013;68(11–12):754–767. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Teti M, Massie JS, Patel A, Malebranche DJ, Tschann JM. ‘What does it take to be a man? What is a real man?’: Ideologies of masculinity and HIV sexual risk among Black heterosexual men. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2011;13(05):545–559. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.556201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Diéguez A, Dolezal C, Nieves L, Díaz F, Decena C, Balan I. Looking for a tall, dark, macho man… sexual-role behaviour variations in Latino gay and bisexual men. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2004;6(2):159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC analysis provides new look at disproportionate impact of HIV and Syphilis among U.S. gay and bisexual men. 2010 Retrieved November 15, 2013 from http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/Newsroom/msmpressrelease.html.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, 2009. HIV Surveillance Report. 2011;21 Retrieved November 13, 2013 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Listing of all risk reduction intervention, by characteristic. Compendium of Evidence-Based HIV Behavioral Interventions. 2013a Retrieved November 12 2013 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/research/compendium/rr/characteristics.html.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Risk behavior. HIV/AIDS. 2013b Retrieved November 22, 2013 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/behavior/index.html.

- Clark J, Salvatierra J, Segura E, Salazar X, Konda K, Perez-Brumer A, Coates T. Moderno love: Sexual role-based identities and HIV/STI prevention among men who have sex with men in Lima, Peru. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(4):1313–1328. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0210-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. The many states of HIV in America. Science. 2012;337(6091):168–171. doi: 10.1126/science.337.6091.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW. Masculinities. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW, Messerschmidt JW. Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society. 2005;19(6):829–859. doi: 10.1177/0891243205278639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conner M, McMillan B. Interaction effects in the theory of planned behaviour: Studying cannabis use. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1999;38(2):195–222. doi: 10.1348/014466699164121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50(10):1385–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. 3rd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- D’Anna LH, Margolis AD, Warner LL, Korosteleva OA, O’Donnell LL, Rietmeijer CA, Malotte CK. Condom use problems during anal sex among men who have sex with men (MSM): Findings from the safe in the city study. AIDS Care. 2012;24(8):1028–1038. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.668285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetriou DZ. Connell’s concept of hegemonic masculinity: A critique. Theory and Society. 2001;30(3):337–361. [Google Scholar]

- Deuba K, Ekström A, Shrestha R, Ionita G, Bhatta L, Karki D. Psychosocial health problems associated with increased HIV risk behavior among men who have sex with men in Nepal: A cross-sectional survey. Plos ONE. 2013;8(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. Universal voluntary testing and treatment for prevention of HIV transmission. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301(22):2380–2382. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowsett GW, Williams H, Ventuneac A, Carballo-Diéguez A. ‘Taking it like a man’: Masculinity and barebacking online. Sexualities. 2008;11(1–2):121–141. doi: 10.1177/1363460707085467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes R. Effective HIV prevention requires gender-transformative work with men. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2007;83(3):173–174. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.024950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn P. Men as victims: ‘Victim’ identities, gay identities, and masculinities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27(17):3442–3467. doi: 10.1177/0886260512445378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Fullilove RE, Peacock D. Are HIV/AIDS prevention interventions for heterosexually active men in the United States gender-specific? American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(6):981–984. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Treves-Kagan S, Lippman SA. Gender-transformative interventions to reduce HIV risks and violence with heterosexually-active men: A review of the global evidence. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(9):2845–2863. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0565-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi S. Negotiating hegemonic masculinity: The rhetorical strategy of “straight -acting” among gay men. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research. 2009;38(3):193–209. [Google Scholar]

- Farrimond H. Beyond the caveman: Rethinking masculinity in relation to men’s help -seeking. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine. 2012;16(2):208–225. doi: 10.1177/1363459311403943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields EL, Bogart LM, Smith KC, Malebranche DJ, Ellen J, Schuster MA. HIV risk and perceptions of masculinity among young Black men who have sex with men. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50(3):296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields EL, Bogart LM, Smith KC, Malebranche DJ, Ellen J, Schuster MA. “I always felt I had to prove my manhood”: Homosexuality, masculinity, gender role strain, and HIV risk among young black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(1):122–131. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CL, Whetten KD, Hall SA, Kaufman JS, Thrasher AD. Black sexuality, social construction, and research targeting the “down low” (the “DL”) Annals of Epidemiology. 2006;17:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Cooper HF, Osborne AH. Structural and social contexts of HIV risk among African Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(6):1002–1008. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galdas P, Cheater F, Marshall P. Men and health help-seeking behaviour: literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;49(6):616–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan FH, Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Klein DJ. Conceptualization of masculinity and medication adherence among HIV-positive Latino men in Los Angeles, California. Poster presented at the 19th International AIDS Conference; Washington, DC. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia LI, Lechuga J, Zea MC. Testing comprehensive models of disclosure of sexual orientation in HIV-positive Latino men who have sex with men (MSM) AIDS Care. 2012;24(9):1087–1091. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.690507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. The Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Parsons JT, Bimbi DS. The association between penis size and sexual health among men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39(3):788–797. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9439-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Wells BE, Parsons JT. Self-reported penis size and experiences with condoms among gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;42(2):313–322. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9952-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta GR. Gender, sexuality, and HIV/AIDS: The what, the why, and the how. Can HIV AIDS Policy Law Rev. 2000;5(4):86–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN. Redefining masculinity in the age of AIDS: Seropositive gay men and the “buff agenda”. In: Nardi P, editor. Gay masculinities. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1999. pp. 130–151. [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN. An exploration of perceptions of masculinity among gay men living with HIV. The Journal of Men’s Studies. 2001;9(3):413–429. doi: 10.3149/jms.0903.413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Green KA, Wilton L. Masculinity, body image, and sexual behavior in HIV-seropositive gay men: A two-phase formative behavioral investigation using the internet. International Journal of Men’s Health. 2004;3(1):27–42. doi: 10.3149/jmh.0301.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Moeller RW, DeRaleau LB. Steroid use in gay, bisexual, and nonidentified men-who-have-sex-with-men: Relations to masculinity, physical, and mental health. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2008a;9(2):106–115. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.9.2.106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Moeller RW, Siconolfi DE, Jerome RC, Rogers M, Schillinger J. Methamphetamine and poly-substance use among gym-attending men who have sex with men in New York City. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008b;35(1):41–48. doi: 10.1007/s12160-007-9005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Parsons JT. Intentional unsafe sex (barebacking) among HIV-positive gay men who seek sexual partners on the Internet. AIDS Care. 2003;15(3):367–378. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000105423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Parsons JT, Wilton L. Barebacking among gay and bisexual men in New York City: Explanations for the emergence of intentional unsafe behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2003;32(4):351–357. doi: 10.1023/A:1024095016181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Wilton L, Wolitski RJ, Parsons JT, Hoff CC, Bimbi DS. Barebacking identity among HIV-positive gay and bisexual men: Demographic, psychological, and behavioral correlates. AIDS. 2005;19(Suppl1):S27–S35. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000167349.23374.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton CJ, Mahalik JR. Minority stress, masculinity, and social norms predicting gay men’s health risk behaviors. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56(1):132–141. doi: 10.1037/a0014440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RB, Turner H, Coates TJ. Social support, AIDS-related symptoms, and depression among gay men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60(3):463–469. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.3.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennen P. Bear bodies, bear masculinity: Recuperation, resistance, or retreat? Gender & Society. 2005;19(1):25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hergenrather KC, Rhodes SD, Clark G. The employment perspectives study: Identifying factors influencing the job-seeking behavior of persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2005;17(2):131–142. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.3.131.62905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hergenrather KC, Zeglin RJ, Ruda D, Hoare C, Rhodes SD. Masculinity across culture: Implications for counseling male clients. Poster presented at the 14th annual conference of the National Council on Rehabilitation Education; Manhattan Beach, CA. 2014. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JA, Hoffman S, Dworkin SL. Rethinking gender, heterosexual men, and women’s vulnerability to HIV/AIDS. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(3):435–445. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill WA, McNeely C. HIV/AIDS disparity between African-American and caucasian men who have sex with men: intervention strategies for the black church. Journal of Religion and Health. 2013;52(2):475–487. doi: 10.1007/s10943-011-9496-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE, Kagan J, Zajonc RB. Emotions, cognition, and behavior. New York, NY US: Cambridge University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Jarama S, Kennamer J, Poppen PJ, Hendricks M, Bradford J. Psychosocial, behavioral, and cultural predictors of sexual risk for HIV infection among Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2005;9(4):513–523. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns M, Pingel E, Eisenberg A, Santana M, Bauermeister J. Butch tops and femme bottoms? Sexual positioning, sexual decision making, and gender roles among young gay men. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2012;6(6):505–518. doi: 10.1177/1557988312455214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Cherry C, Kalichman MO, Amaral CM, White D, Pope H, Cain D. Integrated behavioral intervention to improve HIV/AIDS treatment adherence and reduce HIV transmission. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(3):531–538. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.197608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegeles SM, Hays RB, Coates TJ. The Mpowerment Project: A community-level HIV prevention intervention for young gay men. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(8):1129–1136. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.86.8_Pt_1.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippax S, Smith G. Anal intercourse and power in sex between men. Sexualities. 2001;4(4):413–434. doi: 10.1177/136346001004004002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight R, Shoveller JA, Oliffe JL, Gilbert M, Frank B, Ogilvie G. Masculinities, ‘guy talk’ and ‘manning up’: A discourse analysis of how young men talk about sexual health. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2012;34(8):1246–1261. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2012.01471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox J, Reddy V, Kaighobadi F, Nel D, Sandfort T. Communicating HIV status in sexual interactions: assessing social cognitive constructs, situational factors, and individual characteristics among South African MSM. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(1):350–359. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0337-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblin BA, Husnik MJ, Colfax G, Huang Y, Madison M, Mayer K, Buchbinder S. Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2006;20(5):731–739. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216374.61442.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, German D, Vlahov D, Galea S. Neighborhoods and HIV: A social ecological approach to prevention and care. American Psychologist. 2013;68(4):210–224. doi: 10.1037/a0032704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant RF, Smalley KB, Aupont M, House AT, Richmond K, Noronha D. Initial validation of the male role norms inventory-revised (MRNI-R) The Journal of Men’s Studies. 2007;15(1):83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Liu WM. The study of men and masculinity as an important multicultural competency consideration. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61(6):685–697. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch I, Brouard PW, Visser MJ. Constructions of masculinity among a group of South African men living with HIV/AIDS: Reflections on resistance and change. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2010;12(1):15–27. doi: 10.1080/13691050903082461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR. Both/and, not either/or: A call for methodological pluralism in research on masculinity. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2014;15(4):365–368. doi: 10.1037/a0037308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Burns SM, Syzdek M. Masculinity and perceived normative health behaviors as predictors of men’s health behaviors. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64(11):2201–2209. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Talmadge WT, Locke BD, Scott RJ. Using the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory to work with men in a clinical setting. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61(6):661–674. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Locke BD, Ludlow LH, Diemer MA, Scott RJ, Gottfried M, Freitas G. Development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2003;4(1):3–25. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.4.1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ. Black men who have sex with men and the HIV epidemic: Next steps for public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(6):862–865. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ. Bisexually active Black men in the United States and HIV: Acknowledging more than the “down low”. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37(5):810–816. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ, Fields EL, Bryant LO, Harper SR. Masculine socialization and sexual risk behaviors among Black men who have sex with men: A qualitative exploration. Men and Masculinities. 2009;12(1):90–112. doi: 10.1177/1097184X07309504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ, Gvetadze R, Millett GA, Sutton MY. The relationship between gender role conflict and condom use among Black MSM. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(7):2051–2061. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PY. Why can’t a man be more like a woman? Reflections on Connell’s masculinities. Gender & Society. 1998;12(4):472–474. [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD, Zamudio A. HIV prevention research: Are we meeting the needs of African American men who have sex with men? Journal of Black Psychology. 2004;30(1):78–105. doi: 10.1177/0095798403260265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett G, Flores S, Peterson J, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS. 2007;21:2083–2091. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina Y, Ramirez-Valles J. HIV/AIDS stigma: Measurement and relationships to psycho-behavioral factors in Latino gay/bisexual men and transgender women. AIDS care. 2013;25(12):1559–68. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.793268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell R. Silence, sexuality and HIV/AIDS in South African schools. The Australian Educational Researcher. 2003;30(1):41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz DA, Hart TA. The influence of physical body traits and masculinity on anal sex roles in gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40(4):835–841. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9754-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B. Moderating effects of age on the alcohol and sexual risk taking association: An online daily diary study of men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:118–126. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutchler MG, McKay T, Candelario N, Liu H, Stackhouse B, Bingham T, Ayala G. Sex drugs, peer connections, and HIV: Use and risk among African American, Latino, and Multiracial young men who have sex with men (YMSM) in Los Angeles and New York. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2011;23(2):271–295. doi: 10.1080/10538720.2011.560100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS Trust. Partnership patterns and HIV prevention amongst men who have sex with men (MSM) London: Author; 2010. Retrieved November 24 2013 from http://www.nat.org.uk/media/Files/Publications/July-2010-Parternship-Patterns-and-HIV-Prevention.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Clerkin EM, Mustanski B. Sensation seeking moderates the effects of alcohol and drug use prior to sex on sexual risk in young men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(3):565–575. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9832-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Cognitive influences on sexual risk and risk appraisals in men who have sex with men. Health Psychology. 2013 doi: 10.1037/hea0000010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieves-Lugo K, Toro-Alfonso J. Challenges to antiretroviral adherence: Health beliefs, social support and gender roles in non-adherent men living with HIV in Puerto Rico. In: Cadena CHG, Lopez JAP, editors. Chonic diseases and adherence behaviors. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers; 2012. pp. 153–173. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM. An interventionist’s guide to AIDS behavioral theories. AIDS Care. 2007;19(3):392–402. doi: 10.1080/09540120600708469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’brien R, Hunt K, Hart G. ‘It’s caveman stuff, but that is to a certain extent how guys still operate’: men’s accounts of masculinity and help seeking. Social science & Medicine. 2005;61(3):503–516. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil JM, Helms BJ, Gable RK, David L, Wrightsman LS. Gender-role conflict scale: College men’s fear of femininity. Sex Roles. 1986;14(5–6):335–350. [Google Scholar]

- Parent MC, Torrey C, Michaels MS. “HIV testing is so gay”: The role of masculine gender role conformity in HIV testing among men who have sex with men. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2012;59(3):465–470. doi: 10.1037/a0028067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL, Rothenberg RR, Kraft JM, Beeker CC, Trotter RR. Perceived condom norms and HIV risks among social and sexual networks of young African American men who have sex with men. Health Education Research. 2009;24(1):119–127. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppen PJ, Reisen CA, Zea M, Bianchi FT, Echeverry JJ. Serostatus disclosure, seroconcordance, partner relationship, and unprotected anal intercourse among HIV-positive Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2005;17(3):227–237. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.4.227.66530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poundstone KE, Strathdee SA, Celentano DD. The social epidemiology of Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency S yndrome. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2004;26:22–35. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Lightfoot M, Brown C. Macro-level approaches to HIV prevention among ethnic minority youth: State of the science, opportunities, and challenges. American Psychologist. 2013;68(4):286–299. doi: 10.1037/a0032917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Préau MM, Leport CC, Salmon-Ceron DD, Carrieri PP, Portier HH, Chene GG, Morin MM. Health-related quality of life and patient-provider relationships in HIV-infected patients during the first three years after starting PI-containing antiretroviral treatment. AIDS Care. 2004;16(5):649–661. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001716441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prejean J, Song R, An Q, Hall H. Subpopulation estimates from HIV incidence surveillance system – United States 2006. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301(2):155–156. [Google Scholar]

- Remien RH, Mellins CA. Long-term psychosocial challenges for people living with HIV: Let’s not forget the individual in our global response to the pandemic AIDS. 2007;21(SUPP/5):S55–S64. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000298104.02356.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeser TW. Masculinities in theory. Oxford, England: Wiley Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD. Innovations in HIV prevention research and practice through community engagement. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Bloom FR, Leichliter JS, Montaño J. Outcomes from a community-based, participatory lay health adviser HIV/STD prevention intervention for recently arrived immigrant Latino men in rural North Carolina. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2009;21(Suppl B):103–108. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Malow RM, Jolly C. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): A new and not-so-new approach to HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2010;22(3):173–183. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.3.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Vissman AT, Stowers J, Miller C, McCoy TP, Hergenrather KC, Eng E. A CBPR partnership increases HIV testing among men who have sex with men (MSM): outcome findings from a pilot test of the CyBER/testing internet intervention. Health Education & Behavior. 2011;38(3):311–320. doi: 10.1177/1090198110379572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridge DT. ‘It was an incredible thrill’: The social meanings and dynamics of younger gay men’s experiences of barebacking in Melbourne. Sexualities. 2004;7(3):259–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Rosser B, Neumaier ER. The relationship of internalized homonegativity to unsafe sexual behavior in HIV-seropositive men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2008;20(6):547–557. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.6.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothgerber H. Real men don’t eat (vegetable) quiche: Masculinity and the justification of meat consumption. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2013;14(4):363–375. doi: 10.1037/a0030379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saez PA, Casado A, Wade JC. Factors influencing masculinity ideology among Latino men. Journal of Men’s Studies. 2009;17(2):116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Blashill AJ, O’Cleirigh CM. Promoting the sexual health of MSM in the context of comorbid mental health problems. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(Suppl 1):S30–S34. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9898-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez FJ, Greenberg ST, Liu W, Vilain E. Reported effects of masculine ideals on gay men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2009;10(1):73–87. doi: 10.1037/a0013513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez FJ, Vilain E. “Straight-Acting Gays”: The relationship between masculine consciousness, anti-effeminacy, and negative gay identity. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012;41(1):111–119. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9912-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez FJ, Westefeld JS, Liu W, Vilain E. Masculine gender role conflict and negative feelings about being gay. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2010;41(2):104–111. doi: 10.1037/a0015805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos G, Beck J, Wilson PA, Hebert P, Makofane K, Pyun T, Ayala G. Homophobia as a barrier to HIV prevention service access for young men who have sex with men. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2013;63(5):e167–e170. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318294de80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott HM, Pollack L, Rebchook GM, Huebner DM, Peterson J, Kegeles SM. Peer social support is associated with recent HIV testing among young black men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0608-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scruton R. Modern manhood. In: Magnet M, editor. Modern sex. Chicago, IL: Ivan R. Dee; 2001. pp. 166–178. [Google Scholar]

- Seibert S, Gruenfeld L. Masculinity, femininity, and behavior in groups. Small Group Research. 1992;23(1):95–112. doi: 10.1177/1046496492231006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shernoff M. Without condoms: Unprotected sex, gay men and barebacking. New York, NY US: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shively MG, de Cecco JP. Components of sexual identity. Journal of Homosexuality. 1977;3(1):41–48. doi: 10.1300/J082v03n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shively MG, de Cecco JP. Components of sexual identity. In: Garnets LD, Kimmel DC, editors. Psychological perspectives on lesbian and gay male experiences. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1993. pp. 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Spence JT, Buckner C. Masculinity and femininity: Defining the undefinable. Gender, power, and communication in human relationships. 1995:105–138. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, Carballo-Diéguez A, Coates T, Goodreau SM, McGowan I, Sanders EJ, Sanchez J. Successes and challenges of HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. The Lancet. 2012;380(9839):388–399. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60955-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skevington SM, Sovetkina EC, Gillison FB. A systematic review to quantitatively evaluate ‘Stepping Stones’: A participatory community-based HIV/AIDS prevention intervention. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(3):1025–1039. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallada J. Promoting new models of masculinity to prevent HIV among men who have sex with men in Nicaragua. Arlington, VA: AIDSTAR-One; 2011. Retrieved November 22 2013 from http://www.aidstar-one.com/sites/default/files/AIDSTAR-One_case_study_msm_nicaragua_fs_lac.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Tate H, George R. The effect of weight loss on body image in HIV-positive gay men. AIDS Care. 2001;13(2):163–169. doi: 10.1080/09540120020027323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor I, Robertson A. The health needs of gay men: a discussion of the literature and implications for nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1994;20(3):560–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb02396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. HIV/AIDS basics. AIDS.org. 2013 Retrieved November 13 2013 from http://aids.gov/hiv-aids-basics/

- Verma RK, Pulerwitz J, Mahendra V, Khandekar S, Barker G, Fulpagare P, Singh SK. Challenging and changing gender attitudes among young men in Mumbai, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 2006;14(28):135–143. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)28261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walen SR, DiGiuseppe R, Dryden W. A practitioner’s guide to rational-emotive therapy. 2nd. New York, NY US: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wei C, Raymond H. Preference for and maintenance of anal sex roles among men who have sex with men: Sociodemographic and behavioral correlates. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40(4):829–834. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9623-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welbourn A. Stepping Stones: A Training Package on HIV/AIDS, Communication, and Relationship Skills. London: ActionAid International; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wester SR, Vogel DL. The psychology of men: Historical developments, current research, and future directions. In: Fouad NA, Carter JA, Subich LM, editors. APA handbook of counseling psychology, vol. 1: Theories, research, and methods. Washington, DC US: American Psychological Association; 2012. pp. 371–396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Widman L, Golin CE, Grodensky CA, Suchindran C. Do safer sex self-efficacy, attitudes toward condoms, and HIV transmission risk beliefs differ among men who have sex with men, heterosexual men, and women living with HIV? AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(5):1873–1882. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0108-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhill B, Samuels CA. Desirable and undesirable androgyny: A prescription for the twenty-first century. Journal of Gender Studies. 2004;13(1):15–28. doi: 10.1080/0958923032000184943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zablotska IB, Imrie J, Prestage G, Crawford J, Rawstorne P, Grulich A, Kippax S. Gay men’s current practice of HIV seroconcordant unprotected anal intercourse: Serosorting or seroguessing? AIDS Care. 2009;21(4):501–510. doi: 10.1080/09540120802270292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zea M, Reisen CA, Poppen PJ, Bianchi FT. Unprotected anal intercourse among immigrant Latino MSM: The role of charcteristics of the person and the sexual encounter. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(4):700–715. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9488-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeglin RJ, Stein JP. Social determinants of health predict state incidence of HIV and AIDS: A short report. AIDS Care. 2014:1–5. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.954983. ahead-of-print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Hart TA, Zheng Y. The relationship between intercourse preference positions and personality traits among gay men in china. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012;41(3):683–689. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9819-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Hart TA, Zheng Y. Attraction to male facial masculinity in gay men in China: Relationship to intercourse preference positions and sociosexual behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;42(7):1223–1232. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]