Abstract

BACKGROUND

Patients are frequently discharged with central venous catheters (CVCs) for home infusion therapy.

OBJECTIVE

To study a prospective cohort of patients receiving home infusion therapy to identify environmental and other risk factors for complications.

DESIGN

Prospective cohort study between March and December 2015.

SETTING

Home infusion therapy after discharge from academic medical centers.

PARTICIPANTS

Of 368 eligible patients discharged from 2 academic hospitals to home with peripherally inserted central catheters and tunneled CVCs, 222 consented. Patients remained in the study until 30 days after CVC removal.

METHODS

Patients underwent chart abstraction and monthly telephone surveys while the CVC was in place, focusing on complications and environmental exposures. Multivariable analyses estimated adjusted odds ratios and adjusted incident rate ratios between clinical, demographic, and environmental risk factors and 30-day readmissions or CVC complications.

RESULTS

Of 222 patients, total parenteral nutrition was associated with increased 30-day readmissions (adjusted odds ratio, 4.80 [95% CI, 1.51–15.21) and CVC complications (adjusted odds ratio, 2.41 [95% CI, 1.09–5.33]). Exposure to soil through gardening or yard work was associated with a decreased likelihood of readmissions (adjusted odds ratio, 0.09 [95% CI, 0.01–0.74]). Other environmental exposures were not associated with CVC complications.

CONCLUSIONS

complications and readmissions were common and associated with the use of total parenteral nutrition. Common environmental exposures (well water, cooking with raw meat, or pets) did not increase the rate of CVC complications, whereas soil exposures were associated with decreased readmissions. Interventions to decrease home CVC complications should focus on total parenteral nutrition patients.

Complications of central venous catheters (CVCs) such as central line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) have been increasingly recognized over the past 3 decades and are reportable as a quality indicator in inpatient settings.1 However, patients needing long-term CVCs for chemotherapy, total parenteral nutrition (TPN), parenteral antimicrobials, and other indications often maintain CVCs at home, with support from home nursing and home infusion agencies.2 The advantages of maintaining CVCs in the home are clear: patients can remain in their usual environments and maintain their independence. More than 1.2 million courses of home infusion therapy are delivered in the United States yearly.3 Despite this, complications associated with CVCs in the home have not been a focus of research or regulation.

Patients with home CVCs are at risk for CLABSI as well as catheter-associated venous thromboembolism (CA-VTE), phlebitis, and occlusion. Criteria for defining home healthcare-associated infections have been published,4 but their implementation varies among home infusion agencies.5 Reported rates of home CLABSI range from 0 to 36 CLABSI per 1,000 CVC-days.6–23 CA-VTEs are another increasingly recognized complication of CVCs,22,24 but rates of home CA-VTEs have not been well described. Risk factors for CVC complications occurring at home have also not been well characterized. In particular, the role of environmental risk factors unique to the home setting, such as exposures to well water, uncooked meats, pets, or soil, has not been explored.

We describe outcomes in a prospective cohort of patients with CVCs discharged from the hospital to the home. We hypothesize that environmental exposures will increase the risk of CVC complications.

METHODS

Cohort

In this prospective cohort, eligible patients were at least 18 years of age and discharged between March and December 2015 with peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) or tunneled CVCs. Patients were ineligible if they were in hospice care, did not speak English, or were unable to verbally consent. Eligible patients were contacted via telephone to consent for the study 2 weeks after hospital discharge, to allow patients time to settle into a routine after hospital discharge. Three attempts were made to contact each patient during business hours.

Setting

We included patients requiring home infusion therapy who were discharged from 2 large tertiary-care academic medical centers affiliated with 1 urban American medical school (Johns Hopkins Hospital and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, Maryland). Home infusion agencies provided medication and supplies, and home nursing agencies provided training and support in CVC care. Patients could have used any home infusion or home nursing agency.

Instrument

Consenting patients underwent an initial 20-minute telephone survey focusing on environmental exposures, readmissions and emergency department visits, and CVC complications. Surveys were repeated monthly while the CVC was in place (Supplemental Table 1). The survey instrument was piloted among 10 patients before the study, with changes made on the basis of their feedback.

Medical charts were abstracted for demographic information, CVC characteristics, CVC indication, clinical data, readmissions, emergency department visits, and CVC complications through 1 month after CVC removal. Interrater reliability for 2 reviewers (S.C.K. and D.W.) was calculated on the basis of CVC complications and readmissions on a subset of 20 patients. On cases reviewed independently where concerns over ascertainment of variable categorization was raised by either reviewer, the reviewers conferred to reach consensus.

Variables

Because few enrolled patients were Asian American, Hispanic, or other racial/ethnic groups, racial/ethnic group was categorized as white, black, or other race. Insurer was characterized as Medicare, Medicaid, private, or self-pay/uninsured. Distance from discharging hospital was calculated from the center of the patient’s home zip code. Patients could have more than 1 indication for CVC. The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI)25 was calculated and dichotomized at 2 on the basis of its distribution with the outcome. CVC-days were calculated as the number of days between hospital discharge and CVC removal.

Environmental exposures (persons doing CVC care, and exposure to well water, pets, soil, or uncooked meats) were considered present if patients had acknowledged these exposures during any of the telephone surveys. Patients could have listed more than 1 person assisting with CVC care. Water source was categorized as well or reservoir/municipal source. Exposure to pets was definedd as a pet in the home. Exposure to soil was definedd as gardening or outdoor yard work. Exposure to raw meats was definedd as handling uncooked poultry, pork, beef, seafood, or other meats.

Outcomes were based on patient self-report and medical chart review. The primary outcome was any CVC complication. CVC complication was having any of the following: CLABSI, CA-VTE, bloodstream infection, tunnel infection, or CVC occlusion, dislodgement, accidental removal, kinking, coiling, breaking, phlebitis, or linking. CA-VTE was definedd as a venous thromboembolism on imaging in any location, because PICCs may be risk factors for upper and lower venous thromboembolisms.22 CLABSI were definedd on the basis of Association for Professionals in Infection Control criteria for CLABSI in home infusion4 (adapted from National Healthcare Safety Network CLABSI definitions26). Bloodstream infection was at least 2 positive cultures of blood samples within 48 hours of CVC removal that did not meet CLABSI criteria.26 CVC occlusion was definedd as a blockage in at least 1 CVC lumen necessitating the medication alteplase to clear the occlusion. CVC complications were measured per 1,000 home CVC-days. The secondary outcome was all-cause admissions within 30 days of hospital discharge. We additionally reported all-cause readmissions throughout the study—that is, within 30 days of CVC removal.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for demographic, clinical, CVC, environmental exposure, and outcome data; the software was Stata, version 14.0 (StataCorp). Predictors included demographic and clinical variables and environmental exposures. Univariate and multivariate Poisson regression was used to estimate predictors of overall CVC complications. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression was used to determine predictors of all-cause 30-day readmissions. Covariates were considered if the association with the outcome of interest had P ≤ .20 (2-sided), and were added in a stepwise fashion if the covariate led to at least 10% change in the point estimate. Soil exposure was removed from the CVC complication model because no patients with soil exposure had CVC complications. P <.05 was considered statistically significant. A total of 220 patients were needed to achieve 80% power to calculate a 50% difference in the primary relationship.

Basic demographic and CVC information as well as 30-day all-cause readmissions were abstracted for the 147 patients who were eligible for the study but either declined participation or were unable to be reached (Supplemental Table 2).

The study was approved as expedited with oral consent by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

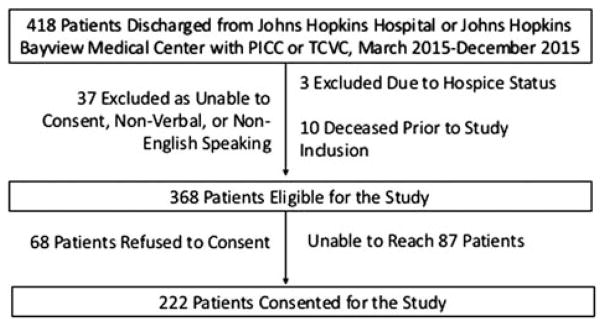

Of 368 eligible patients, 222 (60.3%) enrolled in the study (Figure 1), providing 11,928 CVC-days of data. Most patients were white (160 [72.1%]) and privately insured (151 [68.0%]) (Table 1). Most patients received outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (163 [73.4%]) and had PICCs (145 [65.3%]). Patients maintained CVCs for a mean of 53.6 days after discharge. A minority experienced exposure to soil (17 [7.7%]) (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart for inclusion of participants in study of environmental exposures and the risk of central venous catheter complications and readmissions in home infusion therapy patients.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of 222 Patients Discharged From 2 Academic Medical Centers to Home With Tunneled CVCs and PICCs

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Female sex | 111 (50.0%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 160 (72.1%) |

| Black | 47 (21.2%) |

| Other | 15 (6.8%) |

| Age at discharge, mean (SD), y | 52.7 (14.6) |

| Insurance | |

| Private | 151 (68.0%) |

| Medicaid | 21 (9.5%) |

| Medicare | 48 (21.6%) |

| Uninsured or self-pay | 2 (0.9%) |

| Distance from discharging hospital | |

| <25 km (<15.5 miles) | 106 (47.8%) |

| 25 km to <50 km (15.5 to <31.1 miles) | 46 (20.7%) |

| 50 km to <75 km (31.1 to <46.6 miles) | 28 (12.6%) |

| 75 km to <100 km (46.6 to <62.1 miles) | 15 (6.8%) |

| ≥100 km (≥62.1 miles) | 27 (12.2%) |

| Indication for CVCa | |

| Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy | 163 (73.4%) |

| Chemotherapy | 48 (21.6%) |

| Total parenteral nutrition | 31 (14.0%) |

| Other indication | 17 (7.7%) |

| Type of CVC | |

| PICC | 145 (65.3%) |

| Tunneled CVC | 77 (34.7%) |

| CVC lumens | |

| 1 | 74 (33.3%) |

| 2 | 148 (66.7%) |

| Days with CVC after hospital discharge, mean (SD) | 53.6 (50.8) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 63 (28.4%) |

| Chronic renal disease | 56 (25.2%) |

| Malignant tumor (treated in past 6 months) | 91 (41.0%) |

| Prior venous thromboembolism | 27 (12.2%) |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean (SD) | 5.14 (3.29) |

NOTE. Data are no. (%) of patients unless otherwise indicated. CVC, central venous catheter; PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter.

Patients could have more than 1 indication for CVC; for example, a patient requiring both total parenteral nutrition and outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy would be indicated as having both indications. However, to be noted as having a CVC indication for only venous access for blood draws or for as-needed infusions, this had to be the sole indication for CVC. Other indications included access for intermittent infusions (n =9) and access for phlebotomy (n =8).

TABLE 2.

Environmental and Behavioral Risk Factors Among 222 Patients Discharged From 2 Academic Medical Centers to Home With Tunneled CVCs and PICCs

| Characteristic | No. (%) of patients |

|---|---|

| Person performing infusiona | |

| Self | 151 (68.0%) |

| Friend/family member | 98 (44.1%) |

| Nurse | 19 (8.6%) |

| Presence of pets in the home | |

| Any pet | 122 (55.0%) |

| Dog | 86 (38.7%) |

| Cat | 50 (22.5%) |

| Other mammal (rabbit =2, ferret =1, sugar glider =1) | 4 (1.8%) |

| Fish | 6 (2.7%) |

| Bird | 2 (0.9%) |

| Reptile (turtle =2, lizard =1, snake =1) | 4 (1.8%) |

| Soil exposure via gardening or yard work with CVC in place | 17 (7.7%) |

| Water source: well (unknown =16) | 39/206 (18.9%) |

| Cooking with raw meat with CVC in place | 73 (32.9%) |

NOTE. CVC, central venous catheter; PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter.

Study participants could name more than 1 person performing infusions; for example, if the patient performs infusions during the day, and a significant other performs infusions in the evening; or if a nurse performs infusions on some days and the patient performs infusions on other days.

As shown in Table 3, 52 patients (23.4%) had a CVC complication (4.37/1,000 CVC-days). CA-VTE occurred at a rate of 0.84/1,000 CVC-days, and CLABSI occurred at a rate of 1.18/1,000 CVC-days. More than one-quarter of patients (60 [27.0%]) were readmitted within 30 days of hospital discharge. Of readmitted patients, 8 (13.3%) had planned readmissions, 14 (23.3%) had readmissions related to a CVC complication, and 10 (16.7%) were outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy patients with worsening infections.

TABLE 3.

Prevalence and Rates of Outcomes Among 222 Patients Discharged to Home From 2 Academic Medical Centers With Tunneled CVCs and PICCs

| Outcome | No. (%) of patients | Rate per 1,000 home CVC-days (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Readmission at any time during study | 97 (43.7%) | N/A |

| Readmission within 30 days of hospital discharge | 60 (27.0%) | N/A |

| Readmission related to CVC complication (of 60 30-day readmissions) | 14/60 (23.3%) | N/A |

| Unplanned readmissions (of 60 30-day readmissions) | 52/60 (86.7%) | N/A |

| ED visit at any time during study | 69 (31.1%) | N/A |

| ED visit within 30 days of hospital discharge | 43 (19.4%) | N/A |

| ED visit within 30 days for CVC complication (of 43 visits) | 12/43 (27.9%) | N/A |

| Catheter occlusion resulting in alteplase | 21 (9.5%) | 1.77 (1.15–2.71) |

| CVC inadvertently removed or fell out | 3 (1.4%) | 0.25 (0.08–0.78) |

| Catheter-associated venous thromboembolism | 10 (4.5%) | 0.84 (0.45–1.56) |

| CLABSI | 14 (6.3%) | 1.18 (0.70–1.99) |

| BSI not meeting CLABSI criteria | 8 (3.6%) | 0.67 (0.34–1.35) |

| Any CVC complication | 52 (23.4%) | 4.37 (3.33–5.74) |

NOTE. There were 11,928 total central venous catheter (CVC)–days (days between hospital discharge and removal of CVC). BSI, bloodstream infection; CLABSI, central line–associated bloodstream infection; ED, emergency department; PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter.

We found that having Medicaid as a payer (versus having private insurers as payers) was associated with CVC complications on unadjusted analyses (incidence rate ratio, 2.44 [95% CI, 1.09–5.47]), but was no longer significant once we adjusted for covariates (Table 4). TPN was associated with an increased rate of CVC complications (incidence rate ratio, 1.96 [95% CI, 1.09–3.53]; adjusted incidence rate ratio, 2.41 [95% CI, 1.09–5.33]). No environmental exposures were associated with CVC complications.

TABLE 4.

Univariable and Multivariable Associations of Characteristics With Readmissions and Total CVC Complications Among 222 Patients Discharged With Tunneled CVCs and PICCs

| Variable | Any CVC complication (N =52)

|

Readmission within 30 Days (N =60)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| IRR (95% CI) | Adjusted IRR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Female sex (vs male) | 1.05 (0.61–1.81) | N/A | 1.10 (0.76–2.20) | Not included |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | – | – | – | Not included |

| Black | 1.52 (0.81–2.87) | N/A | 0.85 (0.41–1.78) | Not included |

| Other | 0.74 (0.18–3.06) | N/A | 0.38 (0.08–1.76) | Not included |

| Age ≥50 y | 0.60 (0.34–1.05) | 0.73 (0.37–1.41) | 1.30 (0.69–2.45) | 1.38 (0.62–3.05) |

| Insurancea | ||||

| Private | – | – | – | – |

| Medicaid | 2.44 (1.09–5.47) | 1.66 (0.64–4.31) | 0.48 (0.13–1.71) | 0.49 (0.12–2.06) |

| Medicare | 0.60 (0.28–1.29) | 0.64 (0.27–1.52) | 1.57 (0.79–3.15) | 1.40 (0.60–3.29) |

| Distance from discharging hospital | ||||

| <25 km (referent) | – | N/A | – | – |

| 25 to <50 km | 1.18 (0.59–2.37) | N/A | 1.03 (0.47–2.28) | 1.11 (0.43–2.89) |

| 50 to <75 km | 1.14 (0.49–2.66) | N/A | 2.54 (1.07–6.00) | 2.28 (0.83–6.27) |

| 75 to <100 km | 1.01 (0.35–2.91) | N/A | Not included | Not included |

| ≥100 km | 0.68 (0.28–1.66) | N/A | 1.23 (0.48–3.14) | 0.96 (0.30–3.03) |

| Tunneled CVC vs PICC | 0.78 (0.45–1.35) | 0.88 (0.43–1.80) | 2.22 (1.21–4.08) | 1.53 (0.66–3.53) |

| Indication for CVC | ||||

| OPAT | 1.37 (0.75–2.49) | 1.42 (0.68–2.97) | 0.57 (0.30–1.08) | 1.53 (0.58–4.04) |

| Chemotherapy | 0.58 (0.30–1.13) | 0.77 (0.29–2.05) | 1.48 (0.74–2.95) | 1.59 (0.55–4.67) |

| TPN | 1.96 (1.09–3.53) | 2.41 (1.09–5.33) | 3.04 (1.39–6.60) | 4.80 (1.51–15.21) |

| Charlson comorbidity index ≥2 | 0.77 (0.41–1.47) | 1.07 (0.51–2.26) | 2.90 (1.28–6.56) | 2.23 (0.85–5.88) |

| Diagnosed with or treated for malignant tumor within 6 mo. | 0.77 (0.45–1.33) | Not included | 1.38 (0.76–2.50) | Not included |

| Chronic renal disease (≥stage III) | 0.61 (0.32–1.16) | Not included | 1.75 (0.92–3.36) | Not included |

| Person performing infusion | ||||

| Patient | 1.58 (0.79–3.15) | Not included | 0.93 (0.50–1.75) | Not included |

| Friend or family | 1.56 (0.83–2.92) | Not included | 1.40 (0.74–2.63) | Not included |

| Nurse | 0.98 (0.55–1.73) | Not included | 0.70 (0.22–2.20) | Not included |

| Pets in the home | 0.85 (0.39–1.81) | 1.37 (0.72–2.61) | 0.91 (0.50–1.66) | 1.74 (0.83–3.69) |

| Well water (vs municipal or reservoir water) | 1.11 (0.64–1.91) | 0.77 (0.34–1.75) | 1.10 (0.50–2.39) | 0.59 (0.20–1.71) |

| Soil exposure from gardening or yard work | 0.89 (0.43–1.84) | 0.00 (Not included) | 0.15 (0.03–0.69) | 0.09 (0.01–0.74) |

| Handling of raw meats | 1.22 (0.70–2.12) | 1.52 (0.82–1.75) | 0.60 (0.31–1.16) | 0.62 (0.28–1.41) |

NOTE. CVC, central venous catheter; IRR, incidence rate ratio; OPAT, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy; OR, odds ratio; PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; TPN, total parenteral nutrition.

Two uninsured patients are missing.

TPN was also associated with an increased likelihood of 30-day readmissions (odds ratio [OR], 3.04 [95% CI, 1.39–6.60]; adjusted OR, 4.80 [95% CI, 1.51–15.21]). Living a moderate distance from the discharging hospital (>50 but <75 km) was associated with an increased likelihood of readmissions compared with living near the hospital (<25 km) in unadjusted analyses (OR, 2.54 [95% CI, 1.07–6.00]), but this was no longer statistically significant once adjusted for covariates. Tunneled CVCs (vs PICCs) were associated with an increased likelihood of 30-day readmissions (OR, 2.22 [95% CI, 1.21–4.08]), but this was also no longer statistically significant once adjusted for covariates. CCI at least 2 was also associated with an increased likelihood of 30-day readmissions (OR, 2.90 [95% CI, 1.28–6.56]), but this was no longer statistically significant once adjusted for covariates. Of the environmental exposures, person doing the infusion, pets, well water, and cooking with raw meats were not associated with readmissions. However, soil exposure (through gardening or yard work) was associated with a decreased likelihood of readmission (OR, 0.15 [95% CI, 0.03–0.69]; adjusted OR, 0.09 [95% CI, 0.01–0.74]).

We examined whether there were differences in characteristics between eligible patients who did and did not participate in the study, and found none (Supplemental Table 2).

We calculated differences between the 2 raters on the clinical outcomes. Agreement was very good on all measures: readmissions (κ =0.80), CA-VTE (κ =1.00), CLABSI (κ =1.00), and bloodstream infection (κ =1.00).

DISCUSSION

Complications among patients with home CVCs are common yet underappreciated, and the risks associated with these are not well described. Understanding relationships between environmental exposures and CVC complications is key to counseling patients, as a survey of pediatric home TPN providers showed inconsistency even in advising children with CVCs to avoid swimming.27 In our prospective cohort of patients on home infusion therapy, almost one-quarter had a complication from their catheter. Similarly, more than one-quarter of these patients were readmitted within 30 days of discharge. Our study reinforces the burden of CVC complications and readmissions among home infusion therapy patients.

As in other studies, TPN was associated with both CVC complications and 30-day readmissions.6 Patients on TPN may be more likely to have CLABSI owing to poor venous access that necessitates attempts at catheter salvage and owing to the infusate creating a favorable microorganism environment.6 Preparing TPN requires multiple manipulations to the infusate by patients and caregivers. The complexity of the tasks required in preparing TPN may further predispose patients to CLABSI. Also, TPN components may lead to increased CVC occlusions. Many readmissions in TPN patients may be due to CVC complications. However, patients needing TPN may also have more severe illnesses. Although the CCI counts and weights comorbidities, it is not a measure of illness severity, so we did not fully control for severity of illness.

Interestingly, having Medicaid (but not Medicare) as a payer was associated with CVC complications on unadjusted analyses. Perhaps Medicaid patients are more likely to have comorbidities or other risk factors (such as smoking) that increase the risk of CVC complications. Also, age was not associated with an increased rate of CVC complications or likelihood of readmissions, as in other studies showing that age was not associated with CLABSI,28,29 CVC occlusion,28 other line events,29 or readmissions.30–33

Additional risk factors for readmissions were noted on univariate analyses but were no longer significant when we adjusted for confounders. Tunneled CVCs, higher CCI scores, and living more than 50 but less than 75 km from the hospital were each associated with fewer 30-day readmissions, but these relationships were no longer significant after adjustment. Patients with tunneled CVC are more likely to be on treatments like TPN or chemotherapy, so controlling for receipt of TPN or chemotherapy may make the association between tunneled CVC and readmissions nonsignificant. Similarly, CCI scores are partially driven by malignant tumor,25 so adjustment for chemotherapy may make relationships between CCI and readmissions nonsignificant. Because the discharging hospitals are tertiary referral centers, patients living further away may be sicker than local patients using the hospitals for routine conditions, and controlling for comorbidities may make the relationship between distance and readmissions nonsignificant.

Our primary goal was to examine whether home environmental factors increased the CVC complication rate. No environmental exposures investigated were associated with CVC complications. Interestingly, soil exposure was associated with a decreased likelihood of readmissions. Although this was surprising, as we had hypothesized that patients exposed to soil would have a higher rate of CVC complications, potentially leading to readmissions, it is possible that patients who are able to garden or perform yard work are healthier than other patients in the cohort. In addition, this study is likely under-powered to understand the role of environmental exposures in CVC complications.

Readmissions were frequent. Our population had a 27.0% 30-day readmission rate, higher than the 16% 30-day readmission rate among Medicare patients in the state where the study took place and in the 2 hospitals involved in the study.34 To reduce readmissions in this population requires close management of other comorbidities, reduction of CVC complications, and aggressive management of underlying infections among patients receiving outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy.

This study had several limitations. First, our study involved a small number of patients and we enrolled only 3 in 5 eligible patients. Fortunately, those patients who participated and those who did not had similar basic demographic and clinical features and 30-day readmissions, suggesting that there was not participation bias. Second, this study focused on patients discharged from 2 academic medical centers in 1 major American city, so results may not be generalizable to other regions and may represent a best-case scenario. Third, processes of care and outcomes in other settings where outpatient infusion therapy is delivered (such as outpatient infusion centers) may be different than in our population. We focused on this group because complications experienced in primarily self-administered home infusion therapy are important to highlight and likely different from complications experienced in an outpatient infusion center, where a patient may be at home with a CVC but where a trained medical professional in a clinic performs tasks associated with the infusion or the CVC. Fourth, because most of our patient population receives home infusion therapy after hospital discharge, we focused on this population. Our results may not reflect those starting home infusion therapy as outpatients. Fifth, our results may not apply to patients receiving infusion therapy via midlines, medi-ports, or other types of access. We focused on PICCs and tunneled CVCs because the processes of maintaining these catheters were similar.

Our study included a telephone survey in which we asked patients about complications and environmental risks. This allowed us to capture a more complete picture of complications and exposures—that is, a more complete picture of patient experiences—than we would have with medical chart review alone. For example, patients received services from many home infusion agencies, most of which were not integrated into the shared medical records system of the hospitals studied. If a complication was documented by the home infusion agency but not by a provider affiliated with the hospitals, the complication would have been undercounted.

We have described outcomes among patients receiving home infusion therapy. Nationally, we know relatively little about home infusion patients because typical database sources (such as Medicare) used to study other conditions may be incomplete for studies of home infusion therapy: Medicare does not cover many home infusion services.35 Medicare status and increased age were not associated with CVC complications or 30-day readmissions in this study. Given that alternatives to home infusion therapy may include skilled nursing home stays, extended acute inpatient hospital stays, suboptimal oral therapies, or daily visits to infusion centers, we can reassess whether Medicare should cover home infusion therapies to the same level as private insurers.35 Patients on Medicare who do not have secondary insurances may not be covered for all infusion-related services and equipment needed.35 Congressional bills to remedy this disparity in services are currently pending in committee.36,37

The current study also supports the need to better benchmark CVC complications among home infusion patients; using rigorous criteria in defining CVC outcomes (as in this study) demonstrates that CVC complications may occur at a rate of 4.37/1,000 home CVC-days. A 2011 survey of home infusion pharmacies serving pediatric oncology patients showed that none used all elements of the National Healthcare Safety Network/Association for Professionals in Infection Control CLABSI definition and adjudication process.5 A national registry of home infusion patients would allow for better benchmarking of outcomes.

Home infusion therapy provides a safe way for patients to receive therapies in the home and is increasingly used to avoid hospitalizations and control costs. Traditional risk factors may play a larger role in complications than environmental risk factors. More studies in home infusion therapy are needed to understand the frequency of complications and how to reduce them, particularly in high-risk subpopulations such as TPN patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of Vicky Belotserkovsky and Nekia Murphy of the Johns Hopkins Home Care Group, for their assistance with providing the study team a database of eligible participants; Terri Taylor and home care coordinators at Johns Hopkins Hospital and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, for their assistance with introducing patients to the study; and members of the Johns Hopkins Home Care Group staff and Patient Family Advisory Council, for their comments on the results of the study.

Financial support. National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational research (KL2 Award KL2TR001077 to S.C.K.); the Sherrilyn and Ken Fisher Center for Environmental Infectious Diseases Discovery Award (to S.C.K. and T.P.M.); and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Prevention Epicenter Program (collaborative agreement U54 CK000447 to S.E.C. and T.M.P.).

Footnotes

Presented in part: IDWeek 2015, San Diego, California, October 2015; the National Home Infusion Association Conference, New Orleans, Louisiana, March 2016; the Translational Science Conference, Washington, DC, April 2016; and the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America Annual Conference, Atlanta, Georgia, May 2016.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ice.2016.223

References

- 1.Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1–45. doi: 10.1086/599376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathwani D, Tice A. Ambulatory antimicrobial use: the value of an outcomes registry. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;49:149–154. doi: 10.1093/jac/49.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Home Infusion Association (NHIA) The NHIA industry-wide data initiative phase I: 2010 NHIA provider survey comprehensive aggregate analysis report. [Accessed May 10, 2016];NHIA website. http://www.nhia.org/Data/phase1.cfm. Published 2016.

- 4.Association of Professionals in Infection Control (APIC) APIC-HICPAC surveillance definitions for home health care and home hospice infections. [Accessed May 10, 2016];APIC website. http://www.apic.org/Resource_/TinyMceFileManager/Practice_Guidance/HH-Surv-Def.pdf. Published 2008.

- 5.Rinke ML, Bundy DG, Milstone AM, et al. Bringing central line-associated bloodstream infection prevention home: CLABSI definitions and prevention policies in home health care agencies. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39:361–370. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(13)39050-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shang J, Ma C, Poghosyan L, Dowding D, Stone P. The prevalence of infections and patient risk factors in home health care: a systematic review. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42:479–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crispin A, Thul P, Arnold D, Schild S, Weimann A. Central venous catheter complications during home parenteral nutrition: a prospective pilot study of 481 patients with more than 30,000 catheter days. Onkologie. 2008;31:605–609. doi: 10.1159/000162286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.John BK, Khan MA, Speerhas R, et al. Ethanol lock therapy in reducing catheter-related bloodstream infections in adult home parenteral nutrition patients: results of a retrospective study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2012;36:603–610. doi: 10.1177/0148607111428452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santarpia L, Alfonsi L, Tiseo D, et al. Central venous catheter infections and antibiotic therapy during long-term home parenteral nutrition: an 11-year follow-up study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2010;34:254–262. doi: 10.1177/0148607110362900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moureau N, Poole S, Murdock MA, Gray SM, Semba CP. Central venous catheters in home infusion care: outcomes analysis in 50,470 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:1009–1016. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61865-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shirotani N, Iino T, Numata K, Kameoka S. Complications of central venous catheters in patients on home parenteral nutrition: an analysis of 68 patients over 16 years. Surg Today. 2006;36:420–424. doi: 10.1007/s00595-005-3179-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeLegge MH, Borak G, Moore N. Central venous access in the home parenteral nutrition population—you PICC. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2005;29:425–428. doi: 10.1177/0148607105029006425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ireton-Jones C, DeLegge M. Home parenteral nutrition registry: a five-year retrospective evaluation of outcomes of patients receiving home parenteral nutrition support. Nutrition. 2005;21:156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reimund JM, Arondel Y, Finck G, Zimmermann F, Duclos B, Baumann R. Catheter-related infection in patients on home parenteral nutrition: results of a prospective survey. Clin Nutr. 2002;21:33–38. doi: 10.1054/clnu.2001.0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenheimer L, Embry FC, Sanford J, Silver SR. Infection surveillance in home care: device-related incidence rates. Am J Infect Control. 1998;26:359–363. doi: 10.1016/s0196-6553(98)80018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tokars JI, Cookson ST, McArthur MA, Boyer CL, McGeer AJ, Jarvis WR. Prospective evaluation of risk factors for bloodstream infection in patients receiving home infusion therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:340–347. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-5-199909070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchman AL, Opilla M, Kwasny M, Diamantidis TG, Okamoto R. Risk factors for the development of catheter-related bloodstream infections in patients receiving home parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2013;38:744–749. doi: 10.1177/0148607113491783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Keefe SJ, Burnes JU, Thompson RL. Recurrent sepsis in home parenteral nutrition patients: an analysis of risk factors. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1994;18:256–263. doi: 10.1177/0148607194018003256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White MC, Ragland KE. Surveillance of intravenous catheter-related infections among home care clients. Am J Infect Control. 1994;22:231–235. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(94)99002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rinke ML, Milstone AM, Chen AR, et al. Ambulatory pediatric oncology CLABSIs: epidemiology and risk factors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1882–1889. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johansson E, Bjorkholm M, Bjorvell H, et al. Totally implantable subcutaneous port system versus central venous catheter placed before induction chemotherapy in patients with acute leukaemia—a randomized study. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12:99–105. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0558-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greene MT, Flanders SA, Woller SC, Bernstein SJ, Chopra V. The association between PICC Use and venous thromboembolism in upper and lower extremities. Am J Med. 2015;128:986–993. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marra AR, Opilla M, Edmond MB, Kirby DF. Epidemiology of bloodstream infections in patients receiving long-term total parenteral nutrition. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:19–28. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000212606.13348.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chopra V, O’Horo JC, Rogers MA, Maki DG, Safdar N. The risk of bloodstream infection associated with peripherally inserted central catheters compared with central venous catheters in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:908–918. doi: 10.1086/671737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Hoore W, Sicotte C, Tilquin C. Risk adjustment in outcome assessment: the Charlson comorbidity index. Methods Inf Med. 1993;32:382–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Healthcare Safety Network Device associated module: central line associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) event. [Accessed May 10, 2016];CDC website. http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/4psc_clabscurrent.pdf. Published 2015.

- 27.Miller J, Dalton MK, Duggan C, et al. Going with the flow or swimming against the tide: should children with central venous catheters swim? Nutr Clin Pract. 2014;29:97–109. doi: 10.1177/0884533613515931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox AM, Malani PN, Wiseman SW, Kauffman CA. Home intravenous antimicrobial infusion therapy: a viable option in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:645–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barr DA, Semple L, Seaton RA. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) in a teaching hospital-based practice: a retrospective cohort study describing experience and evolution over 10 years. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;39:407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perez-Lopez J, San Jose Laporte A, Pardos-Gea J, et al. Safety and efficacy of home intravenous antimicrobial infusion therapy in older patients: a comparative study with younger patients. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:1188–1192. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allison GM, Muldoon EG, Kent DM, et al. Prediction model for 30-day hospital readmissions among patients discharged receiving outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:812–819. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cramer S, Fonager K. Risk factors of 30-days re-hospitalization after Hospital at Home in a cohort of patients treated with parenteral therapy. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25:895–899. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huck D, Ginsberg JP, Gordon SM, Nowacki AS, Rehm SJ, Shrestha NK. Association of laboratory test result availability and rehospitalizations in an outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy programme. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:228–233. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Mapping Medicare disparities. [Accessed May 10, 2016];CMS website. https://data.cms.gov/mapping-medicare-disparities. Published 2016.

- 35.Keller S, Pronovost P, Cosgrove S. What Medicare is missing. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:1890–1891. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Home Infusion Association (NHIA) Medicare and home infusion: an NHIA white paper. [Accessed May 10, 2016];NHIA website. http://www.nhia.org/resource/legislative/NHIAMHISOCAWhitePaper.cfm. Published 2015.

- 37.Isakson J. Medicare home infusion site of care act of 2015. [Accessed May 13, 2016];Senate Bill 275, Session 114. http://www.govtrack.us/. Published 2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.