Abstract

Several studies have reported a significant rate of missed colorectal polyps during colonoscopy. This study aimed to determine the variables that affect the miss rate of colorectal polyps.

We performed a retrospective observational study of patients who, between January 2007 and December 2014, had undergone a second colonoscopy within 6 months of their first. In all patients, the first colonoscopy constituted a screening or surveillance colonoscopy as part of a health check-up, and the patients were referred to the endoscopic clinic if there were meaningful polyps. The miss rate of colorectal polyps was evaluated, as were the variables related to these missed lesions.

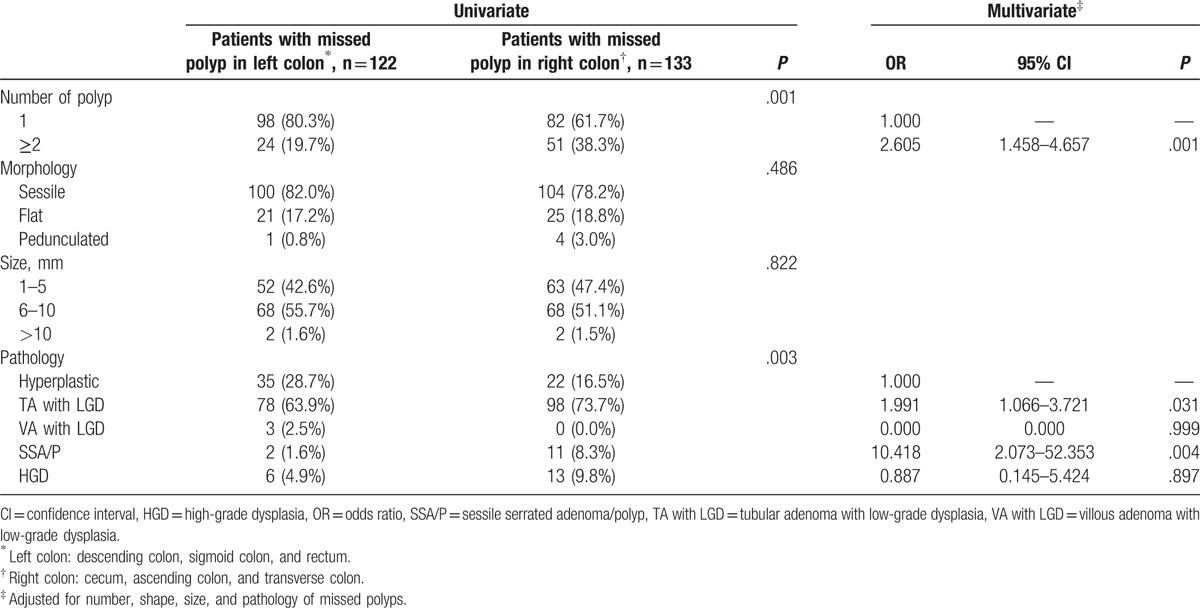

Among 659 patients (535 men), the miss rate of colorectal polyps was 17.24% (372/2158 polyps), and 38.69% of patients (255/659 patients) had at least 1 missed polyp. The most common site for missed polyps was the ascending colon (29.8%), followed by the sigmoid colon (27.8%). The miss rate of polyps was higher in men [odds ratio (OR) = 1.611, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) = 1.024–2.536], patients with multiple polyps at their first colonoscopy (OR = 1.463, 95% CI = 0.992–2.157), and patients who had a history of polyps (OR = 23.783, 95% CI = 3.079–183.694). Multiple missed polyps were more frequently located in the right colon (OR = 2.605, 95% CI = 1.458–4.657), and the risk of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp was greater in the right colon (OR = 10.418, 95% CI = 2.073–52.353).

Endoscopists should pay careful attention in patients who have multiple polyps and in those who have a history of polyps, because such patients are at a high risk of missed polyps in colonoscopy.

Keywords: colonoscopy, miss rate, polys, risk

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most prevalent forms of cancer and causes of cancer-related death worldwide.[1,2] Most CRCs develop from colorectal adenomas, and colonoscopy is regarded as the gold standard method for both detection and resection of such lesions.[3]

However, several studies have reported a significant rate of missed colorectal polyps during endoscopy—from 6% to 28%.[4–7] The reasons for missed polyps are not clear, but 1 previous investigation suggested that when polyps are smaller than 10 mm in diameter, multiple in number, flat in appearance, or located in the left colon, they are associated with a higher miss rate.[6]

It is important to reduce the miss rate of polyps, as it may increase both the risk of interval CRC and health care costs related to improving polyp detection and complete removal.[3,8–10]

Therefore, we conducted the present study to evaluate the variables affecting the miss rate of colorectal polyps, investigating the patients’ characteristics, polyp characteristics, and operator-related factors that influence the rate of missed polyps during colonoscopy.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

We evaluated patients who, between January 2007 and December 2014, had undergone a second colonoscopy for polypectomy or endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) within 6 months of their first colonoscopy. In all patients, the first colonoscopy was conducted as a surveillance or screening colonoscopy as part of a health check-up. If only diminutive polyps were found during the first colonoscopy, they were removed on-site using cold biopsy forceps. However, if the patients had several polyps requiring polypectomy or EMR, a second colonoscopy was performed in an endoscopy clinic using superior equipment. Before the first colonoscopy, all patients completed the demographic and medical history questionnaires, and all underwent a successful cecal intubation. The following patient characteristics were recorded: purpose of colonoscopy, modified Ottawa bowel preparation score, and withdrawal time. The modified Ottawa scale assesses the preparation quality of the entire colon as follows: good—no or minimal solid stool, with large amounts of clear fluid requiring suctioning; fair—collections of semisolid debris that can only be cleared without difficulty; poor—solid or semisolid debris that cannot be effectively cleared. With regard to the polyp characteristics, we noted the number, size, and pathology of the polyps that were found during the first and second colonoscopies. Patients with inflammatory bowel diseases, advanced malignancy of the gastrointestinal tract, or a history of familial polyposis syndrome were excluded, as were those who had previously undergone colonic resection or radiation therapy on their abdomen or pelvis.

The protocol of the present study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board (IIT-2015-481). As the study was based on a retrospective analysis of existing administrative and clinical data, the board waived the requirement for informed consent.

2.2. Colonoscopy procedure

Patients were administered a standardized preparation on the same-day before the secondary colonoscopy; the procedure was performed in the afternoon and involved a large volume of polyethylene glycol (Colyte; Taejoon Pharm. Co. Ltd., Seoul, Republic of Korea) or polyethylene glycol with ascorbic acid (Coolprep; Taejoon Pharm. Co. Ltd., Seoul, Republic of Korea). Each examination was performed by 1 of 5 experienced endoscopists with at least 5 years of experience in colonoscopy, or by 1 of 3 clinical fellows with less than 2 years of endoscopy experience.

All endoscopic examinations were performed under conscious sedation, and bowel preparation was scored using the Ottawa bowel preparation quality scale.[11]

Both the first and second colonoscopies were performed using a forward viewing colonoscope (CF-Q260AL; Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

During the second colonoscopy, all polyps were removed, except in cases of numerous, small, hyperplastic-appearing polyps in the rectum. The polyp size was determined using open biopsy forceps, and the polyps were subdivided on the basis of their histology, as follows: tubular adenoma (TA)—adenoma with tubular components (>75%); villous adenoma (VA)—adenoma with villous components (>50%); sessile serrated adenoma/polyp (SSA/P); high-grade dysplasia (HGD). In addition, the polyps were subdivided on the basis of size (1–5, 6–10, and >10 mm) and location in the colon (cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum). Polyps were also classified macroscopically using the Paris endoscopic classification.[12]

2.3. Calculation of the polyp miss rate

A polyp was considered missed when it was only detected during the second colonoscopy. In such cases, the patient was recorded as having one or more missed polyps. The miss rate of colorectal polyps was calculated as follows: (total number of missed polyps)/(number of missed polyps + number of polyps on the first colonoscopy). The percentage of patients with missed polyps was calculated as follows: (total number of patients with missed polyps)/(total number of patients).

2.4. Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of the missed polyps were presented in terms of their detection status using percentages. The P values of the differences between groups were determined using the Chi-squared or Fisher exact test where appropriate. Variables with P values less than .05 were included in a multivariable logistic regression model to identify the independent risk factors associated with missed polyps. All P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

3. Results

3.1. Miss rate of colorectal polyps

A total of 659 patients (535 men; mean age: 51.36 ± 8.71 years, range: 27–76 years) who had undergone both colonoscopies were enrolled in the study. The first (index) colonoscopy was conducted as a surveillance (46 patients; 6.9%) or screening colonoscopy (613 patients; 93.1%) as part of a health check-up. At the first colonoscopy, a total of 1786 polyps were detected among all patients, and a total of 255 (38.69%) patients were noted as having missed polyps (372 polyps, 289 adenomas) after the second colonoscopy. Therefore, the miss rate of colorectal polyps was 17.24%, and the miss rate of colorectal adenomas was 13.39%.

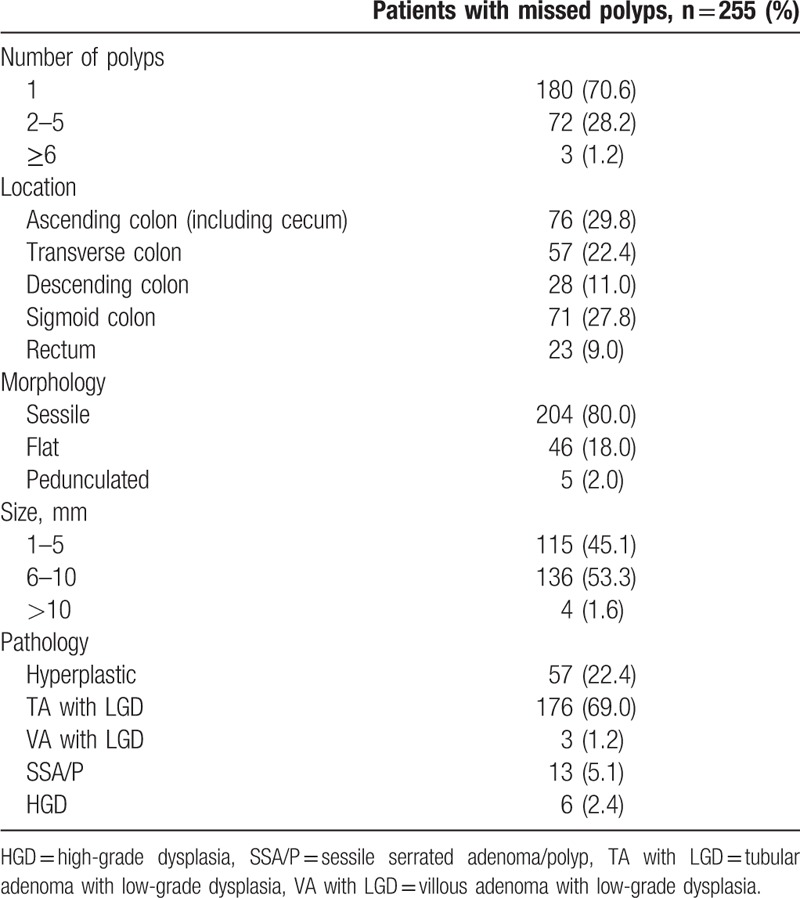

Of the patients with missed polyps, most (70.6%) had only 1 missed polyp, and their pathological finding was TA with low-grade dysplasia (LGD; 69.0%). The most common site of missed polyps was the ascending colon, including the cecum (29.8%), followed by sigmoid colon (27.8%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of missed polyps and relevant patients.

With regard to the effect of the endoscopists’ experience on the miss rate of polyps, there was no significant difference between the well-experienced and less-experienced endoscopists (P = .32).

3.2. The characteristics of patients with missed polyps

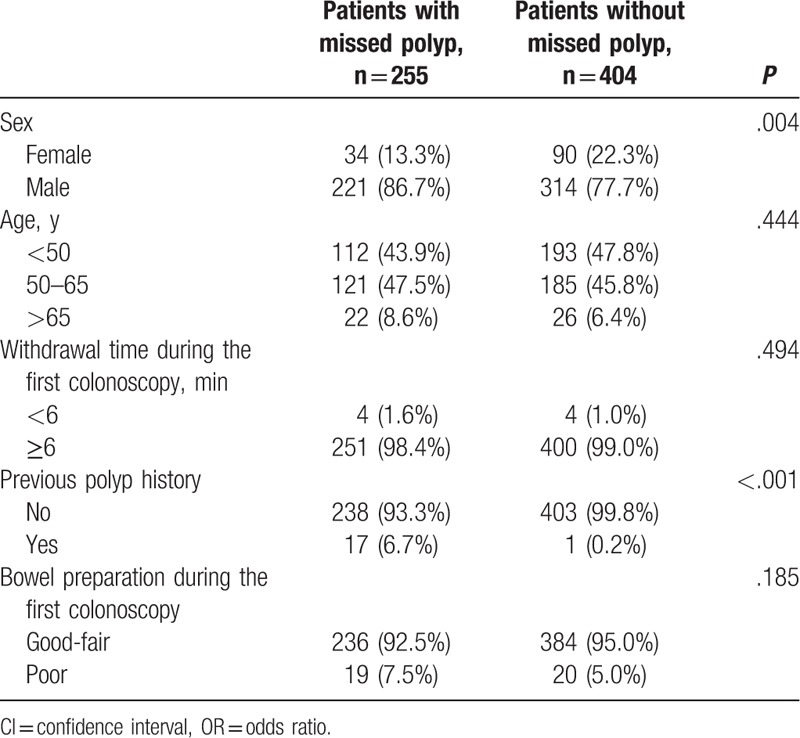

The patient factors associated with missed polyps are summarized in Table 2. Missed polyps were more commonly found in men (P = .004) and in patients with a history of polyps (P < .001). However, withdrawal time during the first colonoscopy (P = .494) and bowel preparation (P = .185) had no effect on the risk of missed polyps.

Table 2.

The statistical analysis of possible patient's factors related to missed polyps.

3.3. The characteristics of missed polyp

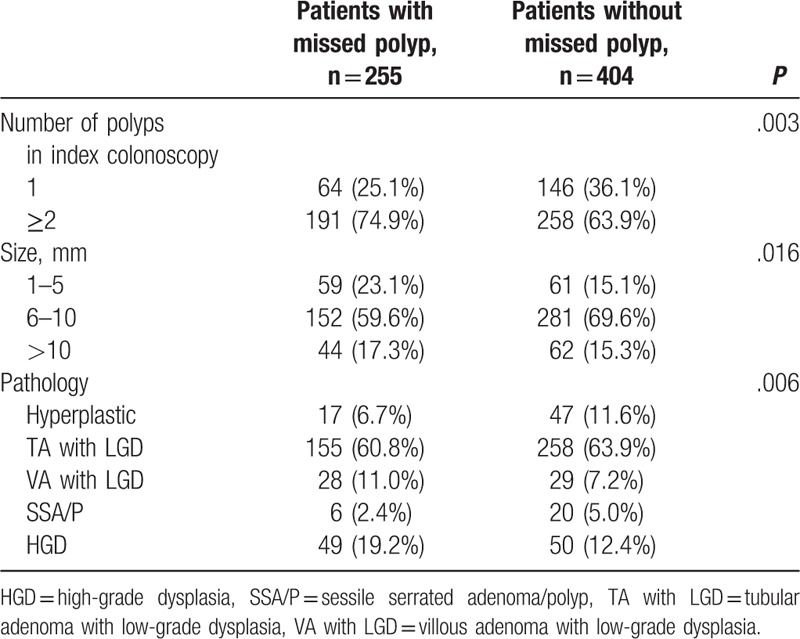

The polyp characteristics associated with missed polyps are summarized in Table 3. The number of polyps in the first (index) colonoscopy affected the miss rate. Most patients with missed polyps (191; 74.9%) showed 2 or more polyps during the first colonoscopy, in contrast to those without missed polyps (P = .003). In addition, the mean size of polyps in the first colonoscopy affected the miss rate. Interestingly, aggressive pathological findings in the first colonoscopy, such as VA with LGD and HGD of polyps, had a significant effect on the miss rate (P = .006).

Table 3.

The statistical analysis of possible polyp factors during the index colonoscopy related to missed polyps.

3.4. Factors associated with missed polyps

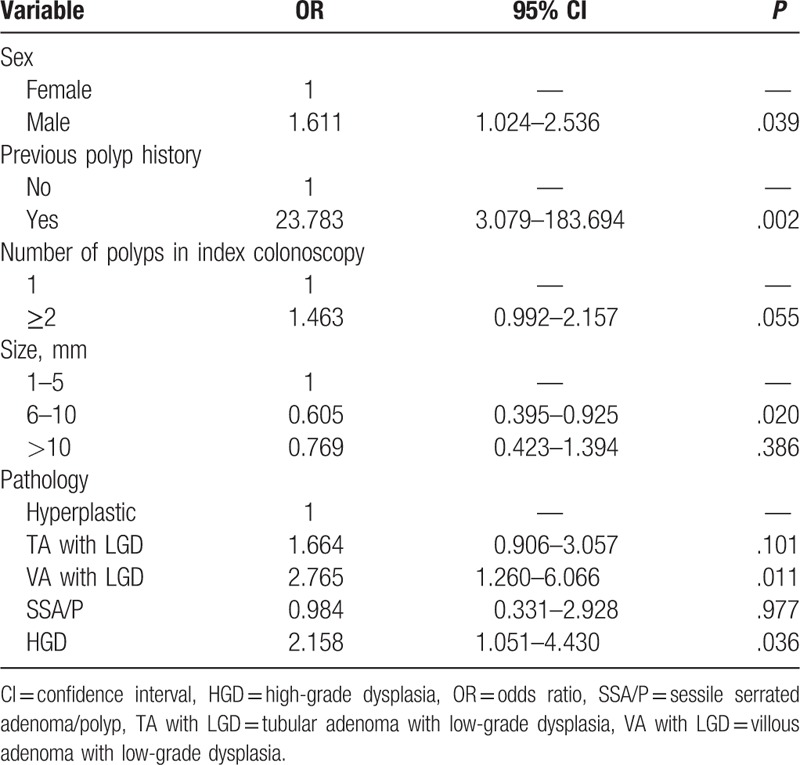

Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the independent variables that were associated with missed polyps. Both patient factors and polyp factors were analyzed. Male sex (P = .039), a history of polyps (P = .002), and polyps with size 6 to 10 mm (P = .020) were independently associated with missed polyps. In addition, aggressive pathology of the polyps during the first colonoscopy was significantly related to missed polyps (Table 4).

Table 4.

The multiple logistic regression analysis of the independent variables during the index colonoscopy associated with missed polyps.

3.5. The location of missed polyps

The location of missed polyps affected their number and pathology. Specifically, 52.2% (133/255) of the patients with missed polyps had them in the right colon, whereas 47.8% (122/255) had them in the left colon. Most of the missed polyps in the right colon were TA with LGD (73.7%; 98/133). On multivariable logistic regression analysis, multiple missed polyps were more frequently located in the right colon [odds ratio (OR) = 2.605, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) = 1.458–4.657], and the risk of SSA/P was greater in the right colon (OR = 10.418, 95% CI = 2.073–52.353; Table 5).

Table 5.

Endoscopic and pathologic characteristics based on the location of missed polyps.

4. Discussion

Even though colonoscopy combined with removal of adenoma is regarded as the gold standard method to prevent CRC, a significant number of polyps are missed for various reasons, and interval cancer is detected in patients with a history of recent colonoscopy. In fact, about 6% of all patients with CRC have had interval cancers.[10,13] In the present study, the miss rate of colorectal polyps was 17.24%, which corroborates previous investigations.[4–7] Furthermore, the present study showed that most (98.4%) missed polyps are smaller than 10 mm in diameter, and that most (98.0%) are sessile or flat in appearance. These results are in line with a systematic review that colonoscopy rarely misses polyps that are over 10 mm, but the miss rate increases significantly for smaller sized polyps.[14]

The most common site of missed polyps is the ascending colon—several studies have corroborated the present investigation in this regard.[6,15–17] Interestingly, patients with 2 or more polyps during the first (index) colonoscopy were at an increased risk of missed polyps (OR = 1.463, 95% CI = 0.992–2.157), although the difference was not statistically significant. These findings were likely due to reduced concentration on the part of the endoscopists, who will have encountered multiple polyps during the index colonoscopy.

In the present study, in addition to the miss rate of polyps, we also investigated the proportion of patients who had missed polyps (38.69%). Moreover, we compared patients with and without missed polyps in terms of factors such as patient characteristics, polyp characteristics, and polyp location. In this regard, it transpired that the purpose of the index colonoscopy had an effect on the miss rate of colorectal polyps. Patients with a history of polyps had a higher risk of missed polyps—about 24 times higher than that of patients with no history of polyps (OR = 23.783, 95% CI = 3.079–183.694).

There may be several reasons for these results. First, patients with a history of polyps might have metachronous polyps. In this regard, surveillance colonoscopy is needed because of accelerated polyp formation or incomplete polyp removal.[13] Second, the results may have been due to reduced attention of the endoscopists during the follow-up colonoscopy after polyp removal; that is, it is likely that they mainly inspected the previous polypectomy site.[6,13]

The miss rate of colorectal polyps was closely independently related to the patient's sex (OR = 1.611, 95% CI = 1.024–2.536), probably because colorectal polyps are themselves more likely to develop in men.[18] In previous studies, sex, age, and body mass index were not associated with missed polyps,[4,5,19] and in the present study, age, withdrawal time, and bowel preparation had no effect on the missed polyp rate, corroborating the results of previous studies.[20,21]

Most patients (94%) in the present study showed an adequate bowel preparation state (good or fair on the modified Ottawa scale). Therefore, bowel preparation conferred no significant difference between patients with and without missed polyps. However, the modified Ottawa scale is too simple method; if we used the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale, which was developed and validated specifically for application during colonoscopy withdrawal and for each segment after all-bowel cleansing,[22] more accurate data may have been obtained.

Regarding the location of the missed polyps, a higher proportion of patients had missed polyps in the right colon than had polyps in the left colon (52.2% vs 47.8%). Moreover, patients with missed polyps in the right colon were at a significantly higher risk of having 2 or more missed polyps than patients with missed polyps in the left colon (OR = 2.605, 95% CI = 1.458–4.657). The risk of a SSA/P was also increased in the right colon (OR = 10.418, 95% CI = 2.073–52.353). These findings are in contrast with previous studies.[15,23,24] However, our results were in line with those of Laiyemo et al,[16] suggesting that missed and recurrent adenomas are more likely to be in the right colon, perhaps because synchronous adenomas are detected more in the right colon.[25,26] In addition, SSA/Ps, which predominantly occur in the right colon, are easily missed because they are small and sessile. Moreover, sometimes it is more difficult to detect SSA/Ps, because they are covered with mucus.[27] Therefore, the endoscopist's efforts are needed to detect and remove SSA/Ps.[28] In a previous study, the location of missed or interval CRC was closely associated with its pathophysiology, because tumor biology can play an important role in the pathogenesis of CRC development,[13,29–31] and because most patients with missed polyps had SSA/P, and several missed polyps were located in right colon in the present study.

Patients with missed polyps in the right colon had more SSA/Ps than patients with missed polyps in the left colon, probably because the proximal colon is more difficult to completely visualize endoscopically than the left colon. Nonetheless, in the present study, the miss rate of colorectal polyps in patients with SSA/P during the first colonoscopy was not statistically greater than the miss rate in patients without SSA/P. Recently, the use of the transparent cap has been known to improve polyp detection. Kondo et al[32] reported that polyp detection rate was higher in the transparent cap group than in the no cap group (49.3% vs 39.1%, P = .04). In addition, a meta-analysis including 12 studies showed that cap-assisted colonoscopy detected significantly more patients with polyps (OR 1.13; P = .030) and had a lower polyp miss rate (12.2% vs 28.6%) than standard colonoscopy.[33] Therefore, use of transparent cap is helpful for examination of right colon, which gives the struggle to endoscopists. Besides transparent cap, special colonoscopic techniques are warranted to detect the flat lesions, including narrow band imaging, chromoendoscopy, and third-eye retroscope.

The present study had several limitations. First, it was conducted in a retrospective manner. Therefore, several variables that affect the development of polyps were missing, including family history, alcohol, and smoking habits. Second, the enrolled patients differed in terms of the purpose of index colonoscopy, and they had a broad age range (27–76 years), so the risk of adenoma development varied widely. However, the main purpose of the present study was to ascertain the number of missed colorectal lesions after colonoscopy, as well as the factors associated with these missed lesions. It was for this reason that we enrolled consecutive patients who had received their second colonoscopy within 6 months. Third, we could not estimate the adenoma detection rate of the individual endoscopists, which is the indicator of colonoscopy quality. To date, several techniques have been used to increase the detection rate of missed lesions, such as wide angle colonoscopy or the retroflection method.[34–36] Therefore, a large, prospective, systematic study is needed to demonstrate which factors affect the miss rate of polyps.

In conclusion, many polyps are missed during colonoscopy, causing an economic burden. When analyzing the factors related to missed polyps, we found that male patients and those with a history of polyps are at an increased risk of missed polyps. Therefore, endoscopists should pay careful attention to avoid missed polyps in these high-risk patients.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, CRC = colorectal cancer, HGD = high-grade dysplasia, LGD = low-grade dysplasia, OR = odds ratio, SSA/P = sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, TA = tubular adenoma, VA = villous adenoma.

Funding/support: This study was supported by Inje University Research Grant 2015.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2012. Cancer Res Treat 2015;47:127–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:5–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lin OS, Kozarek RA, Cha JM. Impact of sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: an evidence-based review of published prospective and retrospective studies. Intest Res 2014;12:268–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Park SY, Moon W, Park SJ, et al. The colonoscopic miss rates of colorectal polyps as determined by a polypectomy. Clin Endosc 2008;36:132–7. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ahn SB, Han DS, Bae JH, et al. The miss rate for colorectal adenoma determined by quality-adjusted, back-to-back colonoscopies. Gut Liver 2012;6:64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Leufkens AM, van Oijen MG, Vleggaar FP, et al. Factors influencing the miss rate of polyps in a back-to-back colonoscopy study. Endoscopy 2012;44:470–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lou GC, Yang JM, Xu QS, et al. A retrospective study on endoscopic missing diagnosis of colorectal polyp and its related factors. Turk J Gastroenterol 2014;25(Suppl 1):182–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pohl H, Robertson DJ. Colorectal cancers detected after colonoscopy frequently result from missed lesions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:858–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lee CK. Clinicopathological characteristics of newly diagnosed colorectal cancers in community gastroenterology practice. Intest Res 2014;12:87–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kim T-O. Development and predictor of interval colorectal cancer. Intest Res 2013;11:153–4. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rostom A, Jolicoeur E. Validation of a new scale for the assessment of bowel preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;59:482–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;58(6 Suppl):S3–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Samadder NJ, Curtin K, Tuohy TM, et al. Characteristics of missed or interval colorectal cancer and patient survival: a population-based study. Gastroenterology 2014;146:950–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].van Rijn JC, Reitsma JB, Stoker J, et al. Polyp miss rate determined by tandem colonoscopy: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Heresbach D, Barrioz T, Lapalus MG, et al. Miss rate for colorectal neoplastic polyps: a prospective multicenter study of back-to-back video colonoscopies. Endoscopy 2008;40:284–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Laiyemo AO, Doubeni C, Sanderson AK, 2nd, et al. Likelihood of missed and recurrent adenomas in the proximal versus the distal colon. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;74:253–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rex DK, Cutler CS, Lemmel GT, et al. Colonoscopic miss rates of adenomas determined by back-to-back colonoscopies. Gastroenterology 1997;112:24–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yamaji Y, Mitsushima T, Ikuma H, et al. Incidence and recurrence rates of colorectal adenomas estimated by annually repeated colonoscopies on asymptomatic Japanese. Gut 2004;53:568–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hong SN, Sung IK, Kim JH, et al. The effect of the bowel preparation status on the risk of missing polyp and adenoma during screening colonoscopy: a tandem colonoscopic study. Clin Endosc 2012;45:404–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].de Wijkerslooth TR, Stoop EM, Bossuyt PM, et al. Differences in proximal serrated polyp detection among endoscopists are associated with variability in withdrawal time. Gastrointest Endosc 2013;77:617–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Doughty AS, et al. Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2533–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Calderwood AH, Jacobson BC. Comprehensive validation of the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;72:686–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Park DH, Kim HS, Kim WH, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and malignant potential of colorectal flat neoplasia compared with that of polypoid neoplasia. Dis Colon Rectum 2008;51:43–9. discussion 49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gschwantler M, Kriwanek S, Langner E, et al. High-grade dysplasia and invasive carcinoma in colorectal adenomas: a multivariate analysis of the impact of adenoma and patient characteristics. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;14:183–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Martinez ME, Sampliner R, Marshall JR, et al. Adenoma characteristics as risk factors for recurrence of advanced adenomas. Gastroenterology 2001;120:1077–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bonithon-Kopp C, Piard F, Fenger C, et al. Colorectal adenoma characteristics as predictors of recurrence. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:323–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rustagi T, Rangasamy P, Myers M, et al. Sessile serrated adenomas in the proximal colon are likely to be flat, large and occur in smokers. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:5271–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Dik VK, Moons LM, Siersema PD. Endoscopic innovations to increase the adenoma detection rate during colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:2200–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lee S, Cho NY, Choi M, et al. Clinicopathological features of CpG island methylator phenotype-positive colorectal cancer and its adverse prognosis in relation to KRAS/BRAF mutation. Pathol Int 2008;58:104–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Leggett B, Whitehall V. Role of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 2010;138:2088–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Seo JY, Choi SH, Chun J, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of endoscopically resected colorectal cancers that arose from sessile serrated adenomas and traditional serrated adenomas. Intest Res 2016;14:270–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kondo S, Yamaji Y, Watabe H, et al. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the usefulness of a transparent hood attached to the tip of the colonoscope. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Westwood DA, Alexakis N, Connor SJ. Transparent cap-assisted colonoscopy versus standard adult colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 2012;55:218–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Choi HN, Kim HH, Oh JS, et al. Factors influencing the miss rate of polyps in a tandem colonoscopy study. Korean J Gastroenterol 2014;64:24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Gralnek IM, Siersema PD, Halpern Z, et al. Standard forward-viewing colonoscopy versus full-spectrum endoscopy: an international, multicentre, randomised, tandem colonoscopy trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:353–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lee HS, Jeon SW. Is retroflexion helpful in detecting adenomas in the right colon? A single center interim analysis. Intest Res 2015;13:326–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]