Abstract

Objectives

Podcasts have the potential to facilitate communication about palliative care with researchers, policymakers and the public. Some podcasts about palliative care are available; however, this is not reflected in the academic literature. Further study is needed to evaluate the utility of podcasts to facilitate knowledge-transfer about subjects related to palliative care. The aims of this paper are to (1) describe the development of a palliative care podcast according to international recommendations for podcast quality and (2) conduct an analysis of podcast listenership over a 14-month period.

Methods

The podcast was designed according to internationally agreed quality indicators for medical education podcasts. The podcast was published on SoundCloud and was promoted via social media. Data were analysed for frequency of plays and geographical location between January 2015 and February 2016.

Results

20 podcasts were developed which were listened to 3036 times (an average of 217 monthly plays). The Rich Site Summary feed was the most popular way to access the podcast (n=1937; 64%). The mean duration of each podcast was 10 min (range 3–21 min). The podcast was listened to in 68 different countries and was most popular in English-speaking areas, of which the USA (n=1372, 45.2%), UK (n=661, 21.8%) and Canada (n=221, 7.3%) were most common.

Conclusions

A palliative care podcast is a method to facilitate palliative care discussion with global audience. Podcasts offer the potential to develop educational content and promote research dissemination. Future work should focus on content development, quality metrics and impact analysis, as this form of digital communication is likely to increase and engage wider society.

Keywords: Technology, palliative care, audio, podcast, Education and training

Background

Technology is increasingly being integrated into medicine to support new opportunities for the delivery of clinical practice, education and research.1 Podcasts are episodic digital audio recordings that are downloaded through web syndication or streamed online.2 Research demonstrates that podcast listenership is increasing.3–5 The percentage of Americans who have listened to a podcast has increased from 9% to 17% between 2008 and 2015.6 Podcasts are increasingly being used to support medical education.7–10 Palliative care podcasts are available;11 these include ‘Get Palliative Care’ (by the Center to Advance Palliative Care—CAPC),12 the ‘CAPC Palliative Care Podcast’13 and the ‘Hospice of the Bluegrass Podcast’.14 However, there are no published studies about the use of podcasts in palliative care. Podcasts can potentially be used to facilitate communication about palliative care with researchers, policymakers and the public.1 Further study is needed to evaluate the utility of podcasts to facilitate knowledge-transfer about subjects related to palliative care.

The aims of this article are to:

Describe the development of a palliative care podcast according to international recommendations for podcast quality.

To analyse the listenership of the podcast over a 14-month period.

Methods

The development of the podcast involved defining the scope and focus of the podcast; developing an infrastructure; identifying quality indicators of podcast quality; designing content; coordinating dissemination and analysing data.

Scope and focus

The podcast was aimed at healthcare professionals with an interest in palliative care, technology and innovation. The podcast method was chosen for its effectiveness, popularity and accessibility.7

Infrastructure development

A portable audio recorder and microphone (total cost=£50) was purchased with funds from an educational grant. SoundCloud, a popular audio streaming website, was chosen to host the podcast (https://soundcloud.com/mypal). The website was accessible online and also has native applications for mobile devices (Android and iOS). An online blog was developed for the podcast (http://amaranwosu.com/amipal/) to facilitate dissemination and provide links to references presented in the podcast.

Quality indicators

Quality indicators for medical education podcasts and blogs have been developed.15 These indicators were developed using a modified Delphi consensus of international healthcare professional educators. The indicators with ≥90% consensus (table 1) consist of 13 items (10 of which are relevant to podcasts) within themes that include: content, credibility, bias, transparency, academic rigour, functionality, use of resources, orientation and professionalism. These quality indicators were used to inform the podcast development.

Table 1.

Quality indicators for medical education podcasts and blogs as recommended by Lin et al15

| Per cent consensus |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality indicator | Domain/subtheme | How this was met | Podcasts | Blogs |

| Do the authorities (eg, author, editor, publisher) that created the resource list their conflicts of interest? | Credibility/bias | There was no conflict of interest. | 100 | 100 |

| Is the information presented in the resource accurate? | Credibility/academic rigour | References were provided for the podcast content. | 100 | 94 |

| Is the identity of the resource's author clear? | Credibility/transparency | The blog and podcast included details of the affiliation and qualifications of ACN. | 95 | 95 |

| Does the resource make a clear distinction between fact and opinion? | Credibility/bias | The podcast and blog provided details of what constituted fact and opinion. References were provided for the podcast content. |

95 | 95 |

| Does the resource employ technologies that are universally available to allow learners with standard equipment and software access? | Design/functionality | The podcast was accessible using standard technologies (computer and mobiles devices) without the requirement of additional software or payment. | 94 | – |

| Does the resource clearly differentiate between advertisement and content? | Credibility/bias | The podcast was freely available and was produced without commercial funding or advertising. | 90 | 95 |

| Is the resource transparent about who was involved in its creation? | Credibility/transparency | Podcast production was performed by ACN. Contributions of others were clearly acknowledged. |

90 | 91 |

| Is the content of this educational resource of good quality? | Content | The podcasts were edited to enhance audio quality. | 90 | 91 |

| Is the content of the resource professional? | Content/professionalism | Each episode was planned and researched in advance to ensure the content was accurate and professional. | 90 | 91 |

| Is the resource useful and relevant for its intended audience? | Content/orientation | The podcast format consisted of interviews, opinion pieces and education-focused activity. The podcast was aimed at palliative care professionals who were familiar with social media. |

90 | 91 |

| Does the resource cite its references? | Credibility/use of other resources | References were provided for the podcast content. | – | 93 |

| Are the resources consistent with its references? | Credibility/use of other resources | References were provided for the podcast content. | – | 93 |

| Is the author well qualified to provide information on the topic? | Credibility/transparency | The blog and podcast included details of the affiliation and qualifications of ACN. | – | 91 |

Content design

The podcast was named AmiPal (previously MyPal), reflecting the name of the corresponding author and subject of Palliative Care. The format involved interviews, opinion pieces and education-focused content. The topics covered are presented in table 2. Podcasts were edited using Audacity (http://www.audacityteam.org), a free open-source, cross-platform audio-editing tool.

Table 2.

Topics covered in AmiPal podcasts since January 2015

| Topic | Focus | Length | Date published |

|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction and welcome to the new podcast | Opinion | 12:02 | Jan 2015 |

| Research and innovation | Opinion | 17:22 | Jan 2015 |

| Integrated clinical academic training | Article overview | 6:13 | Jan 2015 |

| Nanotechnology to monitor cancer | Opinion | 9:34 | Jan 2015 |

| 3D printing in clinical practice | Opinion | 7:15 | Jan 2015 |

| Publishing in palliative care | Education | 15:19 | Feb 2015 |

| Is there too much technology in healthcare | Article overview | 14:55 | Feb 2015 |

| Peer led learning in palliative care | Article overview | 5:35 | Mar 2015 |

| Palliative care day therapy | Interview | 21:42 | Mar 2015 |

| Undergraduate medical education in palliative care | Interview | 15:31 | Mar 2015 |

| Bioelectrical impedance analysis to assess hydration in advanced cancer | Education | 6:14 | Mar 2015 |

| Culture and palliative care | Opinion | 16:27 | May 2015 |

| Wearable technology in healthcare—can palliative care benefit? | Opinion | 14:10 | Jun 2015 |

| Five apps for clinical academics | Education | 16:40 | Jun 2015 |

| Social media and palliative care | Article overview | 4:10 | Sep 2015 |

| Technology in the delivery of healthcare: patient power in medicine | Article overview | 3:44 | Nov 2015 |

| What makes a good case-based discussion? | Interview Education |

5:37 | Dec 2015 |

| Virtual reality and palliative care | Opinion | 5:48 | Feb 2016 |

| Renal medicine and palliative care | Interview | 3:36 | Feb 2016 |

| A comparison between studies: research, audit and service evaluation | Education | 2:22 | Feb 2016 |

Dissemination

The podcasts were released episodically under the ‘Science and Medicine’ category on the SoundCloud website. The podcast's Rich Site Summary (RSS) feed was registered with podcast repositories, including iTunes (http://www.apple.com/itunes), Stitcher (https://www.stitcher.com), TuneIn (http://tunein.com) and Acast (https://www.acast.com). The RSS feed enabled users to access the podcast via a computer or mobile device. Each episode was promoted on social media using palliative medicine hashtags.16 Widgets (stand-alone embeddable web applications) were embedded into the blog and social media posts, which enabled the podcasts to be directly played.

Analysis and feedback

Feedback to each episode was possible using email communication and social media. Additionally, healthcare professionals (in Merseyside, UK) were contacted by email and were encouraged to provide feedback. The listenership analysis was conducted using the SoundCloud analytics tools. Data were analysed for frequency of plays and geographical location.

Results

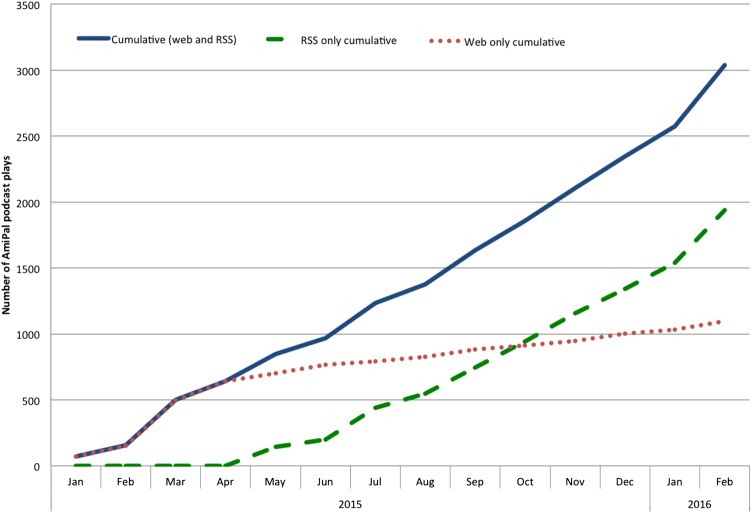

Twenty podcasts were developed between January 2015 and February 2016. The cumulative total of podcast plays was 3036, an average of 217 monthly plays (table 3 and figure 1). The RSS feed was the most popular way to access the podcast (n=1937; 64%). Between January and September 2015, the podcast was most accessed via the SoundCloud website. However, from October 2015, the cumulative RSS feed plays were higher. The mean duration of each podcast was 10 min (range 3–21 min). The podcast was listened to in 68 different countries (table 4) and was most popular in English-speaking areas; specifically, the USA (n=1372, 45.2%), UK (n=661, 21.8%) and Canada (n=221, 7.3%).

Table 3.

Number or times the AmiPal podcast was played, via the web and RSS feed options, between January 2015 and February 2016

| Number of times AmiPal podcast was played (n) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Month | Web only | Web only cumulative | RSS only | RSS only cumulative | Monthly total (web + RSS) | Total cumulative |

| 2015 | Jan | 71 | 71 | 0 | 0 | 71 | 71 |

| Feb | 84 | 155 | 0 | 0 | 84 | 155 | |

| Mar | 344 | 499 | 0 | 0 | 344 | 499 | |

| Apr | 144 | 643 | 0 | 0 | 144 | 643 | |

| May | 61 | 704 | 143 | 143 | 204 | 847 | |

| Jun | 66 | 770 | 55 | 198 | 121 | 968 | |

| Jul | 25 | 795 | 241 | 439 | 266 | 1234 | |

| Aug | 34 | 829 | 107 | 546 | 141 | 1375 | |

| Sep | 56 | 885 | 201 | 747 | 257 | 1632 | |

| Oct | 30 | 915 | 195 | 942 | 225 | 1857 | |

| Nov | 34 | 949 | 217 | 1159 | 251 | 2108 | |

| Dec | 56 | 1005 | 183 | 1342 | 239 | 2347 | |

| 2016 | Jan | 29 | 1034 | 197 | 1539 | 226 | 2573 |

| Feb | 65 | 1099 | 398 | 1937 | 463 | 3036 | |

Figure 1.

Line chart displaying the total number of times the AmiPal podcast was listened to between January 2015 and February 2016 via the SoundCloud web and Rich Site Summary-feed options.

Table 4.

Top 10 geographical locations for AmiPal podcast listeners

| Position | Country | Number of podcast plays (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | USA | 1372 (45.2) |

| 2 | UK | 661 (21.8) |

| 3 | Canada | 221 (7.3) |

| 4 | Australia | 217 (7.1) |

| 5 | Brazil | 164 (5.4) |

| 6 | New Zealand | 69 (2.3) |

| 7 | Germany | 38 (1.3) |

| 8 | India | 26 (0.9) |

| – | The Netherlands | 26 (0.9) |

| 9 | Ireland | 20 (0.7) |

| 10 | Malaysia | 17 (0.6) |

| – | Fifty-seven other countries | 205 (6.8) |

A small amount of feedback was received (10 responses); overall, this was positive. The podcast was modified in response to the feedback with changes to the audio quality, style and format. Specifically, the podcast length shortened to <6 min (evident from the last six podcasts) and backing music was added to improve the rhythmic flow of the audio.

Discussion

Summary

This analysis demonstrated that the AmiPal palliative care podcast had a wide geographical reach with the majority of listeners originating from Western English-speaking countries.

Strengths and uniqueness of this study

This is the first study that describes the development and analysis of a palliative care podcast that was developed according to relevant quality indicators. The podcast was free and accessible across a range of computer and mobile platforms.9 The data of the geographical reach of the podcast provide evidence of the potential of this medium to facilitate international dissemination.

Comparison with previous work

Previous studies have highlighted potential to use technology to inform education and dissemination in palliative care.1 This study adds to evidence from other work, which have used podcasts in medical education.8 10 17 The podcasts were accessed and played several months after release, which may suggest that new listeners were acquired over-time, and/or the archive was used ‘on-demand’. These findings are consistent with previous work, which reports how podcasts provide a repository of information that can be continually accessed.2 18 The majority of podcasts (64%) were accessed via the RSS feed, which may suggest the use of mobile devices. This finding is consistent with the findings of USA and UK research, which demonstrates that two-thirds of podcasts are accessed on a mobile device rather than a computer.4 19 The podcast listenership was similar to the CAPC podcast, which (at the time of writing) has a total of 3831 listens from its 12 episodes over the past 24 months. In 2015, CAPC's public facing ‘Get Palliative Care’ podcast series obtained 14 318 listens from 10 podcasts about the patient journey. This highlights the potential interest for podcasts reporting the patient narrative.

Limitations

The lack of plays from the RSS feed in the first 4 months was due to a delay in the RSS feed being available. Consequently, the potential reach of the podcast in these months was lower. It is likely that the overall proportion of RSS feed plays would have been higher, if the RSS feed was available for the entire period. It is likely that the majority of the RSS feed plays were from mobile devices; however, we cannot ascertain the exact number (as the RSS feed may have been accessed by computer). Furthermore, it is not possible to know whether users listened to the entire podcast or not. Although the podcast was available across a range of computer and mobile devices, there may be some technological challenges to accessing the podcast in some healthcare organisations and resource-poor settings (eg, old internet browsers, web-filtering issues, wireless internet coverage).

Very little feedback was received through the email and social media feedback options. A possible explanation, presented by experts in medical education, may be that the listeners did not place importance on interacting with the podcast host.15 Listeners may personally reflect on the podcast topics without feeling the need to communicate their reflections with the host. Consequently, it is not possible to determine if listeners found the podcasts beneficial. Furthermore, our knowledge of the listenership is relatively unknown, as listeners were not required to provide information or login to access content.

Implications to practice

It is possible to develop a palliative care podcast that has a global reach. Audio recording equipment is available for relatively low cost,20 and many mobile devices contain microphones to record audio.21 Audio hosting sites (eg, SoundCloud.com, Podomatic.com) and open-source audio editing software are freely available (eg, Audacity).20 21 Individuals and organisations planning on developing their own podcasts can use quality indicators15 22 to develop content and social media to enhance dissemination.16 20 If wide dissemination of the podcast is intended, the RSS feed should be registered with podcast databases and social media should be used for promotion.

Future opportunities and research possibilities

Organisations may consider developing podcasts for specific purposes, such as education, lecture capture and research dissemination. Future studies are needed to determine whether palliative care podcasts can facilitate learning for professionals and lay people. Further work can examine the demographics of listeners (eg, using analytics software and surveys) and evaluate learning outcomes of podcasts using of pre and post assessments; this will help to plan priorities for content, quality and to evaluate the impact (eg, for learning and clinical practice) of podcasts. Developed content can be incorporated within the dissemination strategy of institutions, in order to meet learning styles of listeners. Future work can also consider the needs of individuals with hearing deficits (eg, via subtitle video).

Conclusions

Podcasts can be used to facilitate palliative care discussion with a global audience. Podcasts offer the potential to develop educational content and promote research dissemination. Future studies should focus on information development, quality metrics and impact analysis of educational podcasts, as this form of digital communication is likely to increase and engage wider society.

Ethics

This project did not constitute research. Therefore, ethics committee approval was not required.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Amara Nwosu at @amaranwosu

Contributors: ACN designed study, conducted the analysis, interpreted the results and wrote the paper. DM, VLR and LC assisted with the data analysis and provided critical review of the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by an educational grant from the Friends of the University of Liverpool.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data set for the study is available on request.

References

- 1.Nwosu AC, Mason S. Palliative medicine and smartphones: an opportunity for innovation? BMJ Support Palliat Care 2012;2:75–7. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2011-000151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lichtenheld A, Nomura M, Chapin N, et al. Development and implementation of an emergency medicine podcast for medical students: EMIGcast. West J Emerg Med 2015;16:877–8. 10.5811/westjem.2015.9.27293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bond S. Podcasting poised to go from niche to mainstream. 2014. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/edd284ec-65eb-11e4-a454-00144feabdc0.html—axzz41wi739CX (accessed 15 Jun 2016).

- 4.Edison Research. The podcast consumer 2015. 2015. http://www.edisonresearch.com/the-podcast-consumer-2015/ (accessed 15 Jun 2016).

- 5.Davidson L. How Serial shook up the podcasting industry. 2015. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/mediatechnologyandtelecoms/11513025/How-Serial-shook-up-the-podcasting-industry.html (accessed 15 June 2016).

- 6.Vogt N. Podcasting: Fact Sheet Pew Research Center, 2015. http://www.journalism.org/2015/04/29/podcasting-fact-sheet/ (accessed 15 Jun 2016).

- 7.Mallin M, Schlein S, Doctor S, et al. A survey of the current utilization of asynchronous education among emergency medicine residents in the United States. Acad Med 2014;89:598–601. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadjianastasis M, Nightingale KP. Podcasting in the STEM disciplines: the implications of supplementary lecture recording and ‘lecture flipping’. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2016;363 10.1093/femsle/fnw006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meade O, Bowskill D, Lymn JS. Pharmacology podcasts: a qualitative study of non-medical prescribing students’ use, perceptions and impact on learning. BMC Med Educ 2011;11:2 10.1186/1472-6920-11-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cadogan M, Thoma B, Chan TM, et al. Free Open Access Meducation (FOAM): the rise of emergency medicine and critical care blogs and podcasts (2002–2013). Emerg Med J 2014;31:e76–7. 10.1136/emermed-2013-203502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinclair C. Palliative Care Podcasts, 2015. http://www.pallimed.org/2015/05/palliative-care-podcasts.html (accessed 15 Jun 2016).

- 12.Center to Advance Palliative Care. Get Palliative Care, 2016. https://soundcloud.com/get-palliative-care (accessed 15 Jun 2016).

- 13.Center to Advance Palliative Care. CAPC Palliative Care Podcast, 2016. https://soundcloud.com/capc-palliative (accessed 15 Jun 2016).

- 14.Hospice of the Bluegrass. Hospice of the Bluegrass Podcast. http://www.hospicebg.org/podcast/ (accessed 15 Jun 2016).

- 15.Lin M, Thoma B, Trueger NS, et al. Quality indicators for blogs and podcasts used in medical education: modified Delphi consensus recommendations by an international cohort of health professions educators. Postgrad Med J 2015;91:546–50. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-133230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nwosu AC, Debattista M, Rooney C, et al. Social media and palliative medicine: a retrospective 2-year analysis of global Twitter data to evaluate the use of technology to communicate about issues at the end of life. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5:207–12. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alla A, Kirkman MA. PodMedPlus: an online podcast resource for junior doctors. Med Educ 2014;48:1126–7. 10.1111/medu.12556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Copley J. Audio and video podcasts of lectures for campus-based students: production and evaluation of student use. Innov Educ Teach Int 2007;44:387–99. 10.1080/14703290701602805 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Statista: The Statistics Portal. Device distribution of podcast listening time in the United Kingdom (UK) in 2015. 2016. http://www.statista.com/statistics/412226/podcast-listening-by-device-uk/ (accessed 15 Jun 2016).

- 20.Pierson RM. Podcasting on a Budget: How to Record Great Audio for Less. 2015. http://readwrite.com/2015/05/02/audio-podcasting-on-a-budget (accessed 15 Jun 2016).

- 21.Allan P. How to Start Your Own Podcast. 2015. http://lifehacker.com/how-to-start-your-own-podcast-1709798447 (accessed 15 June 2016).

- 22.Thoma B, Chan TM, Paterson QS, et al. Emergency medicine and critical care blogs and podcasts: establishing an international consensus on quality. Ann Emerg Med 2015;66:396–402.e4. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]