Abstract

Background

Fabry disease is an X-linked lysosomal storage disorder caused by GLA mutations, resulting in α-galactosidase (α-Gal) deficiency and accumulation of lysosomal substrates. Migalastat, an oral pharmacological chaperone being developed as an alternative to intravenous enzyme replacement therapy (ERT), stabilises specific mutant (amenable) forms of α-Gal to facilitate normal lysosomal trafficking.

Methods

The main objective of the 18-month, randomised, active-controlled ATTRACT study was to assess the effects of migalastat on renal function in patients with Fabry disease previously treated with ERT. Effects on heart, disease substrate, patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and safety were also assessed.

Results

Fifty-seven adults (56% female) receiving ERT (88% had multiorgan disease) were randomised (1.5:1), based on a preliminary cell-based assay of responsiveness to migalastat, to receive 18 months open-label migalastat or remain on ERT. Four patients had non-amenable mutant forms of α-Gal based on the validated cell-based assay conducted after treatment initiation and were excluded from primary efficacy analyses only. Migalastat and ERT had similar effects on renal function. Left ventricular mass index decreased significantly with migalastat treatment (−6.6 g/m2 (−11.0 to −2.2)); there was no significant change with ERT. Predefined renal, cardiac or cerebrovascular events occurred in 29% and 44% of patients in the migalastat and ERT groups, respectively. Plasma globotriaosylsphingosine remained low and stable following the switch from ERT to migalastat. PROs were comparable between groups. Migalastat was generally safe and well tolerated.

Conclusions

Migalastat offers promise as a first-in-class oral monotherapy alternative treatment to intravenous ERT for patients with Fabry disease and amenable mutations.

Trial registration number:

NCT00925301; Pre-results.

Keywords: Pharmacological chaperone, Fabry disease, lysosomal storage disorder, lyso-Gb3, enzyme replacement therapy

Introduction

Fabry disease is a rare, progressive and devastating X-linked disorder, affecting both males and females, caused by the functional deficiency of lysosomal α-galactosidase (α-Gal).1 The resultant accumulation of glycosphingolipids, including globotriaosylceramide (GL-3) and globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3), can lead to multisystem disease and early death.2

Migalastat, a small-molecule pharmacological chaperone, reversibly binds to the active site of α-Gal. In patients with Fabry disease, migalastat stabilises specific mutant forms of the enzyme and promotes trafficking to lysosomes where α-Gal catabolises accumulated disease substrates.3–8 These mutant forms of α-Gal are defined as amenable to migalastat.

In patients with amenable mutations, orally administered migalastat is a potential alternative treatment to intravenous enzyme replacement therapy (ERT). The burden of lifelong biweekly intravenous infusions may dissuade patients from being treated with ERT or delay ERT initiation and potentially increase the risk of end-organ damage.9 10 In a 5-year retrospective analysis in patients treated with ERT, 40% of males had serum-mediated antibody inhibition of agalsidase activity, which was associated with higher lyso-Gb3, greater left ventricular (LV) mass and decreased renal function.11 An orally administered small molecule, migalastat would avoid ERT-associated immunogenicity and infusion-associated reactions. Additionally, the higher volume of distribution of migalastat (76.5–133 L)12 relative to ERT13 14 suggests enhanced penetration of organs and tissues.4 Theoretically, the chaperoning of α-Gal by migalastat to lysosomes may better mimic natural enzyme trafficking and result in more constant α-Gal activity than biweekly ERT infusions.

We report on the results from the first phase III study that compared the safety and efficacy of migalastat to ERT in male and female patients with Fabry disease and amenable mutations previously treated with ERT.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

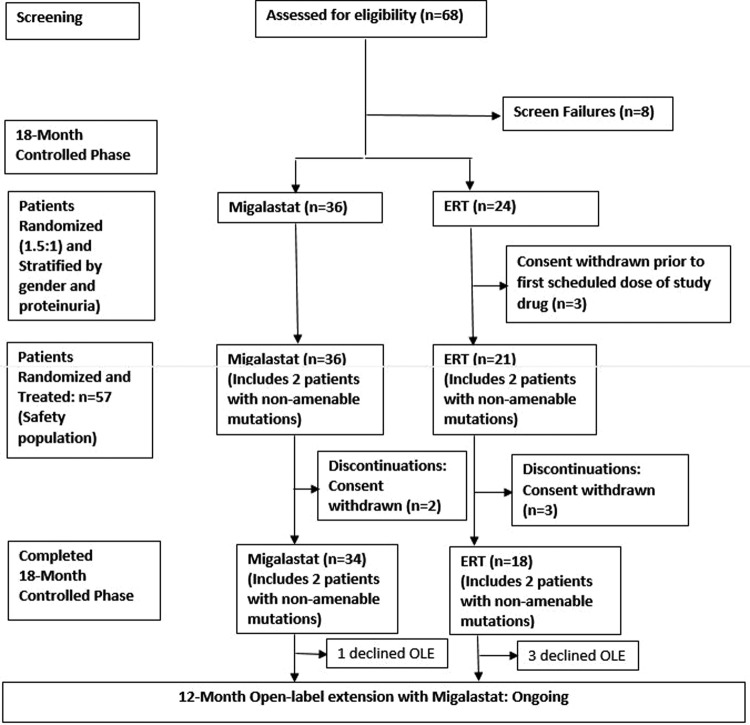

Study AT1001-012 (ATTRACT) (NCT00925301) comprised an 18-month open-label comparison between migalastat and ERT, followed by a 12-month open-label extension with migalastat (figure 1). Patients were maintained on the baseline dose of either agalsidase alfa (0.2 mg/kg) or beta (1.0 mg/kg) biweekly. Following written informed consent, eligibility and baseline assessments, patients were stratified by proteinuria and gender and randomised into the 18-month controlled period. Patients previously treated with ERT (agalsidase alfa and agalsidase beta) for >12 months were randomised 1.5:1 to switch to migalastat HCl (150 mg every other day) or continue ERT. Patients were randomised using interactive response technology (Almac Clinical Technologies). The study received ethics committee/institutional review board (EC/IRB) approval and was conducted according to International Conference on Harmonisation/Good Clinical Practice (ICH/GCP) and the Declaration of Helsinki. This report will focus on the completed 18-month randomised comparison between migalastat and ERT.

Figure 1.

Study design and patient disposition. ERT, enzyme replacement therapy; OLE, open-label extension.

The sample size was determined based on literature reports that the annual decline of iohexol glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in the ERT group was expected to be between 2 and 4 mL/min/1.73 m2 with an SD of approximately 7.5–8.5 mL/min/1.73 m2.15 16

Eligible patients were 16–74 years of age and had the following: a genetically confirmed diagnosis of Fabry disease; initiated ERT ≥12 months before the baseline visit; a responsive GLA mutation based on the preliminary human embryonic kidney-293 (HEK) assay; and an estimated GFR (eGFR) ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Patients taking ACE inhibitors and/or angiotensin II receptor blockers had to be on a stable dose for ≥4 weeks before the screening visit. The primary objective of the study was to determine the comparability of migalastat to ERT in their effects on renal function.

Determination of amenability of GLA mutation

Enrolled patients were required to have responsive mutant α-Gal forms based on a preliminary HEK assay.17 Determination of amenability of the mutant α-Gal forms was based on testing with the Good Laboratory Practice (GLP)-validated HEK assay (GLP HEK assay), which became available during the study. The GLP HEK assay includes several modifications to increase precision and consistency compared with the preliminary assay. Amenable mutant α-Gal forms had to meet the following criteria in the GLP HEK assay: relative increase in α-Gal activity ≥1.2-fold above baseline and absolute increase in α-Gal activity ≥3% of wild type in HEK cells after incubation with 10 µM migalastat.18 The concentration of 10 µM used in the GLP HEK assay is the approximate plasma maximum concentration of migalastat in patients with Fabry disease following a single oral dose of 150 mg.12 α-Gal increases of approximately 1–5% of normal activity in vivo were considered clinically meaningful in patients with Fabry disease.19

Baseline assessment of disease severity and disease course prior to enrolment

The proportion of patients with Fabry multiorgan system disease involvement was determined based on medical history significant for angiokeratoma, neuropathic pain, renal impairment, cardiac event(s), central nervous system event(s) or gastrointestinal symptoms, and the following variables from the pre-randomisation visits: left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) using echocardiography, eGFR, 24-hour urine protein and α-Gal (male patients only). The baseline assessment was compared with that reported for the Fabry Outcomes Survey and Fabry Registry.20–22 The assessment of disease course prior to study enrolment was based on medical history data.

Efficacy assessments

All randomised patients with amenable mutations receiving at least one dose of study drug and having baseline and postbaseline GFR measurements were included in the efficacy analyses. This population was defined as modified intent-to-treat.

Annualised change in GFR

The co-primary end points were annualised changes (mL/min/1.73 m2/year) from baseline through month 18 in calculated GFR by eGFR using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula (eGFRCKD-EPI)23 and measured GFR by iohexol clearance (mGFRiohexol).24 Annualised change in eGFR using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (eGFRMDRD)25 was a secondary end point.

Composite clinical outcome assessment

The number of patients who experienced any of the following renal, cardiac or cerebrovascular events (including death) was determined:

Renal events

a decrease in eGFRCKD-EPI ≥15 mL/min/1.73 m2, with the decreased eGFR <90 mL/min/1.73 m2 relative to baseline;

an increase in 24-hour urine protein ≥ 33%, with elevated protein ≥ 300 mg relative to baseline.

Cardiac events

myocardial infarction;

unstable cardiac angina, as defined by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association national practice guidelines;

new symptomatic arrhythmia requiring antiarrhythmic medication, direct current cardioversion, pacemaker or defibrillator implantation;

congestive heart failure, New York Heart Association class III or IV.

Cerebrovascular events

stroke; transient ischaemic attack.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography measurements were assessed through blinded, centralised evaluation (Cardiocore). Changes from baseline to month 18 were calculated for LV mass index, LV mass, LV posterior wall thickness diastolic (LVPWT), intraventricular septum wall thickness diastolic (IVSWT), LV ejection fraction, diastolic grade (based on E/A ratio), systolic grade (based on ejection fraction) and fractional shortening.

Patient-reported outcomes

Changes from baseline in two questionnaires, the SF-36 v2 Health Survey by QualityMetric26 and the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (Pain Severity Component), were summarised using descriptive statistics.

Plasma globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3)

Plasma was assayed for lyso-Gb3 by liquid chromatography-mass-spectroscopy (LC-MS) at baseline and months 6, 12 and 18. The LC-MS method used 13C6-lyso-Gb3 as an internal standard (lower limit of quantitation: 0.20 µg/L, 0.25 nmol/L).27 28

Safety assessment

All randomised patients receiving at least one dose of study medication were included. A chartered data safety monitoring board regularly reviewed safety data.

Statistical analyses: GFR

Annualised rates of change in mGFRiohexol and eGFRCKD-EPI were analysed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model with the following factors and covariates: treatment group, sex, age, baseline GFR (mGFRiohexol or eGFRCKD-EPI) and baseline 24-hour urine protein. Descriptive statistics on the annualised rate of change were generated for each treatment group from this ANCOVA model, including least-squares means and 95% CIs. Annualised changes in GFR were calculated using linear regression slopes.

The predefined criteria for comparability in the least-squares mean annualised rate of change in mGFRiohexol and eGFRCKD-EPI between migalastat and ERT were a difference between the means in GFR within 2.2 mL/min/1.73 m2/year, and >50% overlap of the 95% CI. The use of these two criteria together provides a comparison similar to a traditional non-inferiority analysis, but is more relevant in rare disease clinical research where traditional non-inferiority analyses are not feasible due to the sample size required. Based on the final observed data, the minimum difference in GFR that the study was able to detect was 0.71 mL/min/1.73 m2/year for eGFR and 1.24 mL/min/1.73 m2/year for mGFR.

Results

Demographics and baseline characteristics

Sixty patients (18–72 years of age; 56% female) were randomised: 36 were switched from ERT to migalastat and 24 remained on ERT. The first patient was enrolled on 8 September 2011. The last patient completed the study on 27 May 2014. Also, 3 of the 24 patients who were randomised to remain on ERT withdrew informed consent before study medication was administered and were not included in the analyses. At baseline, the treatment groups were balanced (table 1). Patients switching to migalastat had been on ERT an average of 3.1 years. Patients remaining on ERT had been receiving ERT for 3.8 years. After randomisation, when the final GLP HEK assay became available, 53 of the 57 treated patients (34, migalastat; 19, ERT) had mutations categorised as amenable. Per the Statistical Analysis Plan, the four patients with non-amenable mutations were excluded from the primary efficacy analyses but were included in the safety analyses. Five randomised and treated patients (all had amenable mutations) discontinued from the study (2/36 migalastat and 3/21 ERT patients). All discontinuations were due to patient withdrawal of informed consent between weeks 16 and 51. Fifty-two patients (34 in the migalastat group; 18 in the ERT group) completed the 18-month randomisation phase (figure 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the safety population

| Migalastat n=36 |

ERT n=21 |

All N=57 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)±SEM (min, max) | 50.5±2.3 (18, 70) |

46.3±3.3 (18, 72) |

48.9±1.9 (18, 72) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 16 (44) | 9 (43) | 25 (44) |

| Female | 20 (56) | 12 (57) | 32 (56) |

| Years since diagnosis (mean±SEM) | 10.2±2.0 | 13.4±2.6 | 11.4±1.6 |

| 24-hour protein (mg/24 hours, mean±SEM) | 267±69 | 360±150 | 301±70 |

| Median | 129 | 108 | 128 |

| IQR | 393 | 483 | 408 |

| Min, max | 0, 2282 | 0, 3154 | 0, 3154 |

| mGFRiohexol (mL/min/1.73 m2, mean±SEM) | 82.4±3.0 | 83.6±5.2 | 82.8±2.6 |

| eGFRCKD-EPI (mL/min/1.73 m2, mean±SEM) | 89.6±3.7 | 95.8±4.1 | 91.9±2.8 |

| eGFRMDRD (mL/min/1.73 m2, mean±SEM) | 83.6±3.7 | 87.8±19.0 | 85.1±28.0 |

| Left ventricular mass index (g/m2) | 97.5±4.7 | 94.6±5.6 | 96.5±3.6 |

| ERT, n (%) | |||

| Agalsidase beta | 11 (31) | 8 (38) | 19 (33) |

| Agalsidase alfa | 24 (67) | 13 (62) | 37 (65) |

| Use of ACEI/ARB/RI, n (%) | 16 (44) | 11 (52) | 27 (47) |

| Amenable GLA mutation, n (%) | 34 (94) | 19 (90) | 53 (93) |

Based on randomised and treated patients. There were no statistically significant differences between treatment groups for these parameters (t-test; Fisher's exact).

ACEI, ACE inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; eGFRCKD-EPI, estimated GFR using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula; eGFRMDRD, annualised change in estimated GFR using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; ERT, enzyme replacement therapy; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; mGFRiohexol, measured GFR using iohexol clearance; RI, renin inhibitor.

At baseline, the majority of patients with amenable mutations had multiorgan system disease (≥88%; see online supplementary table S1). Of the patients with an available date of ERT initiation in their medical history (n=48), 63% had multiorgan system involvement prior to the initiation of ERT, indicating an increase in the percentage of patients with multiorgan disease between initiation of ERT and study baseline (average duration of approximately 3 years). The age at enrolment and start of treatment and percentages of patients with involvement of different organ systems were comparable with those reported for the Fabry Outcomes Survey and Fabry Registry (see online supplementary table S2).20–22

jmedgenet-2016-104178supp001.pdf (218.5KB, pdf)

Based on published reports of clinical phenotypes associated with specific GLA mutations, 19 (36%) patients had mutations associated with the classical phenotype, 21 (40%) with non-classic phenotypes and 2 (4%) with both phenotypes; for the remaining 11 (21%) patients, the phenotype was not previously classified. Also, 10 of the 11 patients, including at least one patient for each of the six unique mutations (3 of 4 for p.G85G), had baseline disease in ≥2 organ systems. There were no significant differences in the phenotype categories between treatment groups.

The amenable mutations are provided in table 2 (supportive references for the literature phenotypes are provided in the online supplementary table S3). To date, 269 GLA mutations have been categorised as amenable to migalastat based on the GLP HEK assay, which has been clinically validated.18

Table 2.

Amenable mutations of enrolled and treated patients and the corresponding clinical phenotype

| Amino acid change (number of patients with the mutation) |

Literature phenotype | Amino acid change | Literature phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| p.M96I | Non-classic | p.G260A | Classic |

| p.L32P (n=3) | Unknown | p.Q279E | Non-classic |

| p.G35R | Non-classic | p.M284T | Classic |

| p.D55V/Q57L | Unknown* | p.M296I | Non-classic |

| p.G85D (n=4) | Unknown* | p.R301P (n=3) | Classic |

| p.A97V | Non-classic | p.R301Q | Both |

| p.R112G | Unknown* | p.G328A | Classic |

| p.R112H | Non-classic | p.Q312R | Non-classic |

| p.A143T (n=3) | Non-classic | p.D322E (n=4) | Classic |

| p.A156T (n=6) | Classic | p.R356Q | Non-classic |

| p.P205T | Classic | p.R363H | Both |

| p.N215S (n=10) | Non-classic | p.L403S | Classic |

| p.Y216C | Classic | p.P409T | Unknown* |

| p.I253S | Unknown* |

Number of patients with each mutation is 1 unless indicated otherwise.

To date, 269 GLA mutations have been categorised as amenable to migalastat based on the Good Laboratory Practice human embryonic kidney assay. The supportive references for the literature phenotypes are provided in the online supplementary table S3.

*Ten of the 11 patients, including at least one patient for each of the six unique mutations (3 of 4 for p.G85D), had baseline disease in ≥2 organ systems.

Effects on renal function

Migalastat and ERT had comparable effects on renal function (table 3). The co-primary end points, eGFRCKD-EPI and mGFRiohexol, met the criteria for comparability: annualised means within 2.2 mL/min/1.73 m2/year and >50% overlap of 95% CIs. Comparison based on medians (results not shown) supports the comparability of migalastat and ERT. The mean change from baseline in 24-hour urine protein was numerically lower for the migalastat group (49.2 mg) than for the ERT group (194.5 mg).

Table 3.

Annualised GFR from baseline to month 18

| ANCOVA* | Migalastat, mean±SEM† (95% CI), n=34 |

ERT, mean±SEM† (95% CI), n=18 |

Means within 2.2 mL/min/1.73 m2/year |

>50% overlap of the 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eGFRCKD-EPI | −0.40±0.93 (−2.27 to 1.48) |

−1.03±1.29 (−3.64 to 1.58) |

Yes | Yes |

| mGFRiohexol | −4.35±1.64 (−7.65 to −1.06) |

−3.24±2.27 (−7.81 to 1.33) |

Yes | Yes |

| eGFRMDRD | −1.51±0.95 (−3.43 to 0.40) |

−1.53±1.32 (−4.20 to 1.13) |

NA | NA |

GFR=mL/min/1.73 m2/year.

*mITT (randomised patients with amenable mutations receiving at least one dose of study medication and having a baseline and postbaseline efficacy measures of eGFRCKD-EPI and mGFRiohexol).

†Least-squares means.

ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; eGFRCKD-EPI, estimated GFR using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula; eGFRMDRD, annualised change in eGFR using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; ERT, enzyme replacement therapy; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; mGFRiohexol, measured GFR using iohexol clearance; mITT, modified intention-to-treat population; NA, not assessed.

Composite clinical outcome assessment

The percentage of patients who experienced renal, cardiac or cerebrovascular events during the 18-month treatment period was 29% for migalastat and 44% for ERT (p=0.36; table 4). No patient died during the 18-month treatment period.

Table 4.

Composite clinical outcome: number of patients (mITT population)

| Component | Migalastat (n=34) | ERT (n=18) |

|---|---|---|

| Renal | 8 (24%) ↑Proteinuria (6), ↓GFR (2) |

6 (33%) ↑Proteinuria (4), ↓GFR (3) |

| Cardiac | 2 (6%) Chest pain, VT/chest pain |

3 (17%) Cardiac failure, dyspnoea, arrhythmia |

| CNS | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) TIA |

| Death | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Any | 10 (29%) | 8 (44%) |

Analyses undertaken in the mITT patients (randomised patients with amenable mutations receiving at least one dose of study drug and having baseline and postbaseline mGFRiohexol and eGFRCKD-EPI measures). Proteinuria event defined as >33% increase in 24-hour urine protein and level >300 mg; GFR event defined as >15 mL/min decline in eGFRCKD-EPI and level <90 mL/min/1.73 m2/year. Two patients in the ERT group experienced one cardiac and one renal event each.

CNS, central nervous system; eGFRCKD-EPI, estimated GFR using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula; ERT, enzyme replacement therapy; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; mGFRiohexol, measured GFR using iohexol clearance; mITT, modified intention to treat; TIA, transient ischaemic attack; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Echocardiography

In patients switched from ERT to migalastat, left ventricular mass index (LVMi) decreased significantly from baseline over 18 months (−6.6 g/m2; 95% CI −11.0 to −2.2); a smaller, non-significant change was observed in patients who remained on ERT (−2.0 g/m2 (−11.0, 7.0)) (table 5; see online supplementary figure S1). The LVMi changes from baseline for migalastat-treated patients were largest for patients with LVH (table 5). LV mass data were consistent with changes in LVMi (results not shown).

Table 5.

Echocardiography-derived changes in patients with amenable mutations

| Parameter | Baseline mean | Change from baseline to month 18 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Migalastat: LVMi (g/m2) | ||

| All (n=33) (% abnormal) | 95.3 (39) | −6.6 (−11.0 to −2.2)* |

| LVH† at baseline (9 females and 4 males) | 116.7 | −8.4 (−15.7 to 2.6) |

| ERT: LVMi (g/m2) | ||

| All (n=16) (% abnormal) | 92.9 (31) | −2.0 (−11.0 to 7−0) |

| LVH† at baseline (n=5) (1 female and 4 males) |

123.3 (100%) | 4.5 (−20.9 to 30.0) |

| Migalastat: LVPWT (cm) | ||

| All (n=33) | 1.17 | −0.035 (−0.077 to 0.007) |

| ERT: LVPWT (cm) | ||

| All (n=16) | 1.08 | 0.029 (−0.037 to 0.094) |

| Migalastat: IVSWT (cm) | ||

| All (n=33) | 1.16 | 0.058 (−0.200 to 0.140) |

| ERT: IVSWT (cm) | ||

| All (n=16) | 1.18 | 0.037 (−0.051 to 0.124) |

LVMi (g/m2): normal: female, 43–95, male, 49–115; LVPMT (cm): normal: female, 0.6–<1.0, male, 0.6–<1.1; IVSWT (cm): normal: female, 0.6–0.9, male, 0.6–1.0.

*Statistically significant (95% CI does not overlap zero).

†LVH; defined as LVMi (g/m2) >95 (females) or >115 (males).

ERT, enzyme replacement therapy; IVSWT, intraventricular septal wall thickness; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; LVMi, left ventricular mass index; LVPMT, left ventricular posterior wall thickness; LVPWT, left ventricular posterior wall thickness diastolic.

The baseline mean and changes at month 18 for IVSWT and LVPWT are provided in table 5. The changes in LVMi over 18 months correlated with changes in IVSWT (r2=0.26, p=0.0028) but not with changes in LVPWT (r2=0.04, p=0.296).

LV ejection fraction and fractional shortening were generally normal at baseline and remained stable over 18 months. Systolic and diastolic functional grades were normal at baseline in the majority of patients and remained stable over 18 months (see online supplementary table S4).

Plasma lyso-Gb3

In patients with amenable mutations, plasma lyso-Gb3 levels remained low and stable following the switch from ERT to migalastat (see online supplementary figure S2). Comparable results were found in both males and females and in patients previously receiving either agalsidase alfa or agalsidase beta following their switch from ERT to oral migalastat. In two male patients with non-amenable mutations, plasma lyso-Gb3 increased following the switch from ERT to migalastat compared with the two patients with non-amenable mutations (one male; one female) who remained on ERT.

Patient-reported outcomes

Scores on the SF-36 v2 and Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) Short Form-Pain Severity Component remained stable during the 18-month study for both treatment groups (see online supplementary table S4).

Safety

Treatment with migalastat was generally safe and well tolerated. The frequency of treatment-emergent adverse event (AE)s in the migalastat and ERT groups was comparable (94% and 95%, respectively). The most frequently reported treatment-emergent AEs (≥25%) in the migalastat group were nasopharyngitis (33%) and headache (25%). These events had a comparable frequency in the ERT group (33% and 24%, respectively). Most treatment-emergent AEs were mild or moderate in severity. No patient discontinued study drug due to a treatment-emergent AEs.

There were no deaths in the study. Serious AEs (SAEs) were less common in the migalastat group (19%) than in the ERT group (33%). No SAEs were considered related to study drug.

No clinically relevant effect of migalastat and no clinically relevant treatment group differences were noted for any laboratory test, ECG variable, vital sign or physical finding.

Discussion

Oral migalastat, a pharmacological chaperone, is being developed as an alternative to ERT in the treatment of Fabry disease. Migalastat reversibly binds to the active site of specific mutant forms of α-Gal (amenable GLA mutations) and stabilises and promotes trafficking of the enzyme to lysosomes where α-Gal catabolises accumulated disease substrate. We report on the 18-month results from a phase III study comparing the safety and efficacy of migalastat to ERT in male and female patients with Fabry disease and amenable mutations previously treated with ERT.

The study enrolled and treated 57 patients based on a preliminary HEK assay for responsiveness of the mutant α-Gal to migalastat. Prior to completing the study, the amenability of these mutant forms was assessed using the final GLP HEK assay, which was not available during enrolment. Based on this assay, 53 of the 57 patients had amenable mutations. On the basis of published reports, 36% had GLA mutations associated with the classical Fabry phenotype and 40% had GLA mutations associated with the non-classic Fabry phenotype. The baseline characteristics and medical histories indicated that a majority of patients in the study had multiple-organ systems affected by Fabry disease. The classic Fabry phenotype has been used to describe patients with early-onset, low-residual α-Gal activity (in male patients) and multiorgan system disease including pain and angiokeratoma in both males and females.29–32

Migalastat and ERT had comparable effects on renal function, assessed by mGFRiohexol and eGFRCKD-EPI (the co-primary end points), and eGFRMDRD in patients with amenable mutations. The 18-month period is sufficient to show a treatment effect, based on data in the literature demonstrating a worsening of renal function over 12–15 months after stopping ERT treatment33 or reducing ERT dose.34 A separate study with migalastat in ERT-naive patients8 also demonstrated that renal function was stabilised following up to 24 months of treatment. Renal dysfunction is present in a majority of patients being treated for Fabry disease,35 progresses over time and can lead to end-stage renal disease.36–41 Patients were stratified based on gender and 24-hour urine protein, which are the most important factors impacting renal function in patients with Fabry disease.39 42 The progressive decrease in GFR in Fabry disease has also been shown to be a major risk factor for cardiac events.43 Studies in the literature show that annualised rates of decline in GFR are in the range of −2.2 to −2.9 in ERT-treated patients.16 44 45 Thus, the effect of ERT is to slow the decline in GFR in patients with Fabry disease. As shown in this study, migalastat has a comparable effect to ERT on renal function, so it has the potential to stabilise or slow decline in renal function, which is an important treatment goal in Fabry disease.

The study found that LVMi decreased significantly from baseline to month 18 in patients treated with migalastat, whereas a smaller non-significant change was observed in patients remaining on ERT. The two treatment groups were balanced. Based on the randomisation ratio (1.5:1), there were fewer patients in the ERT group, which potentially limits the ability to show a statistically significant change. Cardiac disease is currently the main cause of death in patients with Fabry disease.35 The most common cardiac manifestation of Fabry disease is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.46 LVH is an important risk factor for predicting cardiac events (heart failure and myocardial infarction) in Fabry disease.43 47 Reduction of LV mass has been associated with improved outcomes in Fabry disease; a 3-year study in patients with Fabry disease without myocardial fibrosis found that post-treatment reductions in LV mass were associated with improvement in stress exercise.48 The reductions in LVMi in migalastat-treated patients in this study correlate with changes in septal wall thickness but not posterior wall thickness. These reductions are especially meaningful compared with the known progressive increase of LVMi in untreated patients with Fabry disease47 49 and may contribute to a reduction in cardiac complications. The effect of ERT on LV mass is inconsistent.50–52 Engelen et al51 reported that the initial improvements observed with ERT decreased over a similar time interval. In a cohort of 45 adult patients treated with agalsidase alfa for approximately 10 years, Kampmann et al53 reported no changes in LVMi in patients with baseline values <50 g/m2 but found a decrease in LVMi in males with baseline values ≥50 g/m2. A separate study found that LVMi increased in all male age groups treated for ≥2 years with agalsidase beta, except those 18–29 years of age.47 The reduction in LVMi with migalastat treatment, which was also demonstrated in a separate study of 24 months in ERT-naive patients,8 may reflect the wide tissue distribution of migalastat as an orally administered small molecule, including penetration into cardiac muscle cells, although further study is warranted.

The findings from the composite clinical outcome analysis provided further support for the efficacy and safety of migalastat. Previous studies have evaluated the effect of treatment on the progression of Fabry disease by a composite analysis of events related to the renal, cardiac and cerebrovascular systems,52 54 55 which are the organ systems most associated with morbidity and mortality in Fabry disease.36 38 46 In this study, the frequency of events in the migalastat group was 29% versus 44% in the ERT group, indicating that the effect of migalastat compares favourably to ERT in these composite clinical events. Results from both patient-reported outcomes showed that patients experienced no reduction in their quality of life when switched from ERT to migalastat.

Migalastat and ERT had similar effects on Fabry disease substrate in the study. Plasma lyso-Gb3 is recognised as an important marker of disease severity,31 56 and reductions in this substrate have been demonstrated to be associated with improved outcomes in Fabry disease.56 In patients with amenable mutations, migalastat maintained plasma lyso-Gb3 at the same low levels as ERT. In patients with non-amenable mutations, plasma lyso-Gb3 increased when the patients were switched from ERT to migalastat. The clear differences in plasma lyso-Gb3 in migalastat-treated patients with amenable versus non-amenable mutations, as previously demonstrated in a separate study,8 support the accuracy and clinical validity of the GLP HEK assay in categorising GLA mutations.18

Based on the proportion of patients with amenable mutations from the Sakuraba listing of Fabry phenotypes,57 the findings from the GLP HEK assay18 and literature reports of screenings in neonates,58–60 it is estimated that 35–50% of patients with Fabry disease have amenable mutations and therefore may be treatable with migalastat.

Migalastat was generally safe and well tolerated in this study. No clinically relevant effects were seen in laboratory tests, ECGs, vital signs or physical exams.

In this study, 18 months of treatment with migalastat was associated with a statistically significant decrease in LVMi; in ERT-treated patients, a non-significant change was observed. Migalastat and ERT had similar treatment effects on renal function and compared favourably in a composite clinical end point. Migalastat was safe and well tolerated. Migalastat, a pharmacological chaperone, offers promise as a first-in-class oral alternative to ERT for male and female patients with Fabry disease with amenable mutations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families, and the clinical investigators who participated in the ATTRACT study. The authors acknowledge the important contributions of clinical investigator Professor Akemi Tanaka, Osaka City University Hospital, who passed away during the course of the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: the study was designed by the authors, who vouch for accuracy of the analyses and protocol adherence. Data collection and analyses were undertaken by the sponsor in collaboration with a core group of investigators. The first draft of the manuscript was led by the first author and reviewed by all authors. All authors provided final approval to submit the manuscript for publication.

Funding: Amicus Therapeutics, Cranbury, NJ, USA.

Competing interests: JB, ERB, JPC, NSk, FJ, JK, CV and JY report being employed by Amicus Therapeutics and owning shares; DJL and PB are former employees of Amicus Therapeutics; CB is a former contractor of Amicus Therapeutics; JPC and DJL report issued patents without royalties related to this study. DGB, DPG, DD, PD, UF-R, OG-A, DAH, AJ, EL, RS, SPS, and WRW report personal fees from Amicus Therapeutics, outside the submitted work. WRW reports receiving fees from Genzyme, Shire and Protalix. KN reports receiving fees from Shire and Genzyme. SPS reports receiving fees from Shire, Biomarin, Protalix and Genzyme. TO reports receiving fees from Genzyme and Dainippon Sumitomo. RL reports receiving fees from Genzyme. AJ reports receiving fees from Genzyme and Shire. OG-A reports receiving fees from Genzyme, Shire and Pfizer. DAH reports receiving fees from Genzyme, Shire and Protalix. UF-R reports receiving fees from Shire and Genzyme.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Several IRBs approved this study. The institutions were those in which the principal investigators undertook this clinical trial.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Brady RO, Gal AE, Bradley RM, Martensson E, Warshaw AL, Laster L. Enzymatic defect in Fabry's disease. Ceramidetrihexosidase deficiency. N Engl J Med 1967;276:1163–7. 10.1056/NEJM196705252762101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Germain DP. Fabry disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2010;5:30 10.1186/1750-1172-5-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan JQ, Ishii S, Asano N, Suzuki Y. Accelerated transport and maturation of lysosomal a-galactosidase A in Fabry lymphoblasts by an enzyme inhibitor. Nat Med 1999;5:112–15. 10.1038/4801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khanna R, Soska R, Lun Y, Feng J, Frascella M, Young B, Brignol N, Pellegrino L, Sitaraman SA, Desnick RJ, Benjamin ER, Lockhart DJ, Valenzano KJ. The pharmacological chaperone 1-deoxygalactonojirimycin reduces tissue globotriaosylceramide levels in a mouse model of Fabry disease. Mol Ther 2010;18:23–33. 10.1038/mt.2009.220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamin ER, Flanagan JJ, Schilling A, Chang HH, Agarwal L, Katz E, Wu X, Pine C, Wustman B, Desnick RJ, Lockhart DJ, Valenzano KJ. The pharmacological chaperone 1-deoxygalactonojirimycin increases alpha-galactosidase A levels in Fabry patient cell lines. J Inherit Metab Dis 2009;32:424–40. 10.1007/s10545-009-1077-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yam GH, Zuber C, Roth J. A synthetic chaperone corrects the trafficking defect and disease phenotype in a protein misfolding disorder. FASEB J 2005;19:12–18. 10.1096/fj.04-2375com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Germain DP, Fan JQ. Pharmacological chaperone therapy by active-site-specific chaperones in Fabry disease: in vitro and preclinical studies. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009;47(Suppl 1):S111–17. 10.5414/CPP47111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Germain DP, Hughes DA, Nicholls K, Bichet DG, Giugliani R, Wilcox WR, Feliciani C, Shankar SP, Ezgu F, Amartino H, Bratkovic D, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Nedd K, Sharaf El Din U, Lourenco CM, Banikazemi M, Charrow J, Dasouki M, Finegold D, Giraldo P, Goker-Alpan O, Longo N, Scott CR, Torra R, Tuffaha A, Jovanovic A, Waldek S, Packman S, Ludington E, Viereck C, Kirk J, Yu J, Benjamin ER, Johnson F, Lockhart DJ, Skuban N, Castelli J, Barth J, Barlow C, Schiffmann R. Treatment of Fabry disease with the pharmacological chaperone migalastat. N Engl J Med 2016;375:545–55. 10.1056/NEJMoa1510198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weidemann F, Niemann M, Störk S, Breunig F, Beer M, Sommer C, Herrmann S, Ertl G, Wanner C. Long-term outcome of enzyme-replacement therapy in advanced Fabry disease: evidence for disease progression towards serious complications. J Intern Med 2013;274:331–41. 10.1111/joim.12077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weidemann F, Sanchez-Niño MD, Politei J, Oliveira JP, Wanner C, Warnock DG, Ortiz A. Fibrosis: a key feature of Fabry disease with potential therapeutic implications. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013;8:116 10.1186/1750-1172-8-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenders M, Stypmann J, Duning T, Schmitz B, Brand SM, Brand E. Serum-mediated inhibition of enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;27:256–64. 10.1681/ASN.2014121226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson FK, Mudd PN, Bragat A, Adera M, Boudes P. Pharmacokinetics and safety of migalastat HCl and effects on agalsidase activity in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2013;2:120–32. 10.1002/cpdd.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Summary of Product Characteristics: Fabrazyme 35 mg, powder for concentrate for solution for infusion 4444: Genzyme Corporation, 2011. (updated 12/12/2011; cited 4 March 2014). http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/18404/SPC/Fabrazyme+35+mg,+powder+for+concentrate+for+solution+for+infusion/

- 14.Summary of Product Characteristics: Replagal 1mg/ml concentrate for solution for infusion Shire Human Genetic Therapies, 2014. (updated 01/10/2014; cited 4 March 2014). https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/19760/SPC/Replagal+1mg+ml+concentrate+for+solution+for+infusion/

- 15.Waldek S, Germain D, Banikazem M, Guffon N, Lee P, Linthorst G. Abstracts of the World Congress of Nephrology. June 8–12, 2003. Berlin, Germany. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003;18(Suppl 4):630. [Google Scholar]

- 16.West M, Nicholls K, Mehta A, Clarke JT, Steiner R, Beck M, Barshop BA, Rhead W, Mensah R, Ries M, Schiffmann R. Agalsidase alfa and kidney dysfunction in Fabry disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;20:1132–9. 10.1681/ASN.2008080870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu X, Katz E, Della Valle MC, Mascioli K, Flanagan JJ, Castelli JP, Schiffmann R, Boudes P, Lockhart DJ, Valenzano KJ, Benjamin ER. A pharmacogenetic approach to identify mutant forms of a-galactosidase A that respond to a pharmacological chaperone for Fabry disease. Hum Mutat 2011;32:965–77. 10.1002/humu.21530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benjamin ER, Della Valle MC, Wu X, Katz E, Pruthi F, Bond S, Bronfin B, Williams H, Yu J, Bichet DG, Germain DP, Giugliani R, Hughes D, Schiffmann R, Wilcox WR, Desnick RJ, Kirk J, Barth J, Barlow C, Valenzano KJ, Castelli J, Lockhart DJ. The validation of pharmacogenetics for the identification of Fabry patients for treatment with migalastat. Genet Med 2016. Published Online First: 22 Sep 2016. 10.1038/gim.2016.122 10.1038/gim.2016.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desnick RJ. Enzyme replacement and enhancement therapies for lysosomal diseases. J Inherit Metab Dis 2004;27:385–410. 10.1023/B:BOLI.0000031101.12838.c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mauer M, Warnock DG, Politei JM, Yoo H-W, Wanner C. Fabry Registry Annual Report 2014. Genzyme, a Sanofi company, 2014:1–18.

- 21.Eng CM, Fletcher J, Wilcox WR, Waldek S, Scott CR, Sillence DO, Breunig F. Fabry disease: baseline medical characteristics of a cohort of 1765 males and females in the Fabry Registry. J Inherit Metab Dis 2007;30:184–92. 10.1007/s10545-007-0521-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta A, Beck M, Elliott P, Giugliani R, Linhart A, Sunder-Plassmann G, Schiffmann R, Barbey F, Ries M, Clarke JTR. Enzyme replacement therapy with agalsidase alfa in patients with Fabry's disease: an analysis of registry data. Lancet 2009;374:1986–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61493-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang Y, Castro AF III, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604–12. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nilsson-Ehle P. Iohexol clearance for the determination of glomerular filtration rate: 15 years’ experience in clinical practice. eJIFCC 2001;13:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Feldman HI, Greene T, Lash JP, Nelson RG, Rahman M, Deysher AE, Zhang Y, Schmid CH, Levey AS. Evaluation of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Equation in a Large Diverse Population. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;18:2749–57. 10.1681/ASN.2007020199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boutin M, Auray-Blais C. Multiplex tandem mass spectrometry analysis of novel plasma lyso-Gb3-related analogues in Fabry disease. Anal Chem 2014;86:3476–83. 10.1021/ac404000d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benjamin ER, Hamler R, Brignol N, Boyd R, Yu J, Bragat A, Kirk J, Bichet DG, Germain DP, Giugliani R, Hughes DA, Schiffmann R, Wilcox WR, Barth J, Valenzano KJ, Castelli J. Migalastat reduces plasma globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3) in Fabry patients: results from the FACETS phase 3 study. J Inherit Metab Dis 2014;37:S161. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Desnick RJ, Brady R, Barranger J, Collins AJ, Germain DP, Goldman M, Goldman M, Grabowski G, Packman S, Wilcox WR. Fabry disease, an under-recognized multisystemic disorder: expert recommendations for diagnosis, management, and enzyme replacement therapy. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:338–46. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilcox WR, Oliveira JP, Hopkin RJ, Ortiz A, Banikazemi M, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Sims K, Waldek S, Pastores GM, Lee P, Eng CM, Marodi L, Stanford KE, Breunig F, Wanner C, Warnock DG, Lemay RM, Germain DP. Females with Fabry disease frequently have major organ involvement: Lessons from the Fabry Registry. Mol Genet Metab 2008;93:112–28. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rombach SM, Dekker N, Bouwman MG, Linthorst GE, Zwinderman AH, Wijburg FA, Kuiper S, Vd Bergh Weerman MA, Groener JE, Poorthuis BJ, Hollak CE, Aerts JM. Plasma globotriaosylsphingosine: diagnostic value and relation to clinical manifestations of Fabry disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010;1802:741–8. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Echevarria L, Benistan K, Toussaint A, Dubourg O, Hagege AA, Eladari D, Jabbour F, Beldjord C, De Mazancourt P, Germain DP. X-chromosome inactivation in female patients with Fabry disease. Clin Genet 2016;89:44–54. 10.1111/cge.12613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tennankore K, West M, LeMoine K. Withdrawal of enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry disease—indirect evidence of treatment benefit? 39th Annual Meeting of the Canadian Society of Nephrology; Halifax, Nova Scotia, 2007:108. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weidemann F, Krämer J, Duning T, Lenders M, Canaan-Kühl S, Krebs A, González HG, Sommer C, Üçeyler N, Niemann M, Störk S, Schelleckes M, Reiermann S, Stypmann J, Brand SM, Wanner C, Brand E. Patients with Fabry Disease after enzyme replacement therapy dose reduction versus treatment switch. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014;25:837–49. 10.1681/ASN.2013060585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waldek S, Patel MR, Banikazemi M, Lemay R, Lee P. Life expectancy and cause of death in males and females with Fabry disease: Findings from the Fabry Registry. Genet Med 2009;11:790–6. 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181bb05bb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schiffmann R, Warnock DG, Banikazemi M, Bultas J, Linthorst GE, Packman S, Sorensen SA, Wilcox WR, Desnick RJ. Fabry disease: progression of nephropathy, and prevalence of cardiac and cerebrovascular events before enzyme replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:2102–11. 10.1093/ndt/gfp031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ortiz A, Oliveira JP, Waldek S, Warnock DG, Cianciaruso B, Wanner C, Cianciaruso B, Wanner C. Nephropathy in males and females with Fabry disease: cross-sectional description of patients before treatment with enzyme replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23:1600–7. 10.1093/ndt/gfm848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pisani A, Visciano B, Imbriaco M, Di Nuzzi A, Mancini A, Marchetiello C, Riccio E. The kidney in Fabry's disease. Clin Genet 2014;86:301–9. 10.1111/cge.12386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wanner C, Oliveira JP, Ortiz A, Mauer M, Germain DP, Linthorst GE, Serra AL, Maródi L, Mignani R, Cianciaruso B, Vujkovac B, Lemay R, Beitner-Johnson D, Waldek S, Warnock DG. Prognostic indicators of renal disease progression in adults with Fabry disease: natural history data from the Fabry Registry. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5:2220–8. 10.2215/CJN.04340510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Talbot AS, Lewis NT, Nicholls KM. Cardiovascular outcomes in Fabry disease are linked to severity of chronic kidney disease. Heart 2015;101:287–93. 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ortiz A, Cianciaruso B, Cizmarik M, Germain DP, Mignani R, Oliveira JP, Villalobos J, Vujkovac B, Waldek S, Wanner C, Warnock DG. End-stage renal disease in patients with Fabry disease: natural history data from the Fabry Registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010;25:769–75. 10.1093/ndt/gfp554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warnock DG, Ortiz A, Mauer M, Linthorst GE, Oliveira JP, Serra AL, Maródi L, Mignani R, Vujkovac B, Beitner-Johnson D, Lemay R, Cole JA, Svarstad E, Waldek S, Germain DP, Wanner C, Fabry Registry. Renal outcomes of agalsidase beta treatment for Fabry disease: role of proteinuria and timing of treatment initiation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:1042–9. 10.1093/ndt/gfr420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel MR, Cecchi F, Cizmarik M, Kantola I, Linhart A, Nicholls K, Strotmann J, Tallaj J, Tran TC, West ML, Beitner-Johnson D, Abiose A. Cardiovascular events in patients with Fabry disease natural history data from the Fabry Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:1093–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feriozzi S, Schwarting A, Sunder-Plassmann G, West M, Cybulla M. Agalsidase alfa slows the decline in renal function in patients with Fabry disease. Am J Nephrol 2009;29:353–61. 10.1159/000168482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Germain DP, Waldek S, Banikazemi M, Bushinsky DA, Charrow J, Desnick RJ, Lee P, Loew T, Vedder AC, Abichandani R, Wilcox WR, Guffon N. Sustained, long-term renal stabilization after 54 months of agalsidase β therapy in patients with fabry disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;18:1547–57. 10.1681/ASN.2006080816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weidemann F, Niemann M, Warnock DG, Ertl G, Wanner C. The Fabry cardiomyopathy: models for the cardiologist. Annu Rev Med 2011;62:59–67. 10.1146/annurev-med-090910-085119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Germain DP, Weidemann F, Abiose A, Patel MR, Cizmarik M, Cole JA, Beitner-Johnson D, Benistan K, Cabrera G, Charrow J, Kantola I, Linhart A, Nicholls K, Niemann M, Scott CR, Sims K, Waldek S, Warnock DG, Strotmann J. Analysis of left ventricular mass in untreated men and in men treated with agalsidase-β: data from the Fabry Registry. Genet Med 2013;15:958–65. 10.1038/gim.2013.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weidemann F, Niemann M, Breunig F, Herrmann S, Beer M, Störk S, Voelker W, Ertl G, Wanner C, Strotmann J. Long-term effects of enzyme replacement therapy on Fabry cardiomyopathy: evidence for a better outcome with early treatment. Circulation 2009;119:524–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.794529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rombach SM, Smid BE, Linthorst GE, Dijkgraaf MG, Hollak CE. Natural course of Fabry disease and the effectiveness of enzyme replacement therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Inherit Metab Dis 2014;37:341–52. 10.1007/s10545-014-9677-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kampmann C, Linhart A, Devereux RB, Schiffmann R. Effect of agalsidase alfa replacement therapy on Fabry disease—related hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a 12- to 36-month, retrospective, blinded echocardiographic pooled analysis. Clin Ther 2009;31:1966–76. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Engelen MA, Brand E, Baumeister TB, Marquardt T, Duning T, Osada N, Schaefer RM, Stypmann J. Effects of enzyme replacement therapy in adult patients with Fabry disease on cardiac structure and function: a retrospective cohort study of the Fabry Münster Study (FaMüS) data. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000879 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rombach SM, Smid BE, Bouwman MG, Linthorst G, Dijkgraaf MG, Hollak CE. Long term enzyme replacement therapy for Fabry disease: effectiveness on kidney, heart and brain. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013;8:47 10.1186/1750-1172-8-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kampmann C, Perrin A, Beck M. Effectiveness of agalsidase alfa enzyme replacement in Fabry disease: cardiac outcomes after 10 years’ treatment. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2015;10:125 10.1186/s13023-015-0338-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Banikazemi M, Bultas J, Waldek S, Wilcox WR, Whitley CB, McDonald M, Finkel R, Packman S, Bichet DG, Warnock DG, Desnick RJ. Agalsidase-β therapy for advanced Fabry disease: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007;146: 77–86. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-2-200701160-00148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Germain DP, Charrow J, Desnick RJ, Guffon N, Kempf J, Lachmann RH, Lemay R, Linthorst GE, Packman S, Scott CR, Waldek S, Warnock DG, Weinreb NJ, Wilcox WR. Ten-year outcome of enzyme replacement therapy with agalsidase beta in patients with Fabry disease. J Med Genet 2015;52:353–8. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Breemen MJ, Rombach SM, Dekker N, Poorthuis BJ, Linthorst GE, Zwinderman AH, Breunig F, Wanner C, Aerts JM, Hollak CE. Reduction of elevated plasma globotriaosylsphingosine in patients with classic Fabry disease following enzyme replacement therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011;1812:70–6. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sakuraba H. http://www.Fabry-database.org (accessed 25 Sep 2016).

- 58.Mechtler TP, Stary S, Metz TF, De Jesús VR, Greber-Platzer S, Pollak A, Herkner KR, Streubel B, Kasper DC. Neonatal screening for lysosomal storage disorders: feasibility and incidence from a nationwide study in Austria. Lancet 2012;379:335–41. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61266-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin HY, Chong KW, Hsu JH, Yu HC, Shih CC, Huang CH, Lin SJ, Chen CH, Chiang CC, Ho HJ, Lee PC, Kao CH, Cheng KH, Hsueh C, Niu DM. High incidence of the cardiac variant of Fabry disease revealed by newborn screening in the Taiwan Chinese population. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2009;2:450–6. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.862920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spada M, Pagliardini S, Yasuda M, Tukel T, Thiagarajan G, Sakuraba H, Ponzone A, Desnick RJ. High incidence of later-onset Fabry disease revealed by newborn screening. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79:31–40. 10.1086/504601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jmedgenet-2016-104178supp001.pdf (218.5KB, pdf)