Abstract

Background

Variable expressivity and incomplete penetrance between individuals with identical long QT syndrome (LQTS) causative mutations largely remain unexplained. Founder populations provide a unique opportunity to explore modifying genetic effects. We examined the role of a novel synonymous KCNQ1 p.L353L variant on the splicing of exon 8 and on heart rate corrected QT interval (QTc) in a population known to have a pathogenic LQTS type 1 (LQTS1) causative mutation, p.V205M, in KCNQ1-encoded Kv7.1.

Methods

419 adults were genotyped for p.V205M, p.L353L and a previously described QTc modifier (KCNH2-p.K897T). Adjusted linear regression determined the effect of each variant on QTc, alone and in combination. In addition, peripheral blood RNA was extracted from three controls and three p.L353L-positive individuals. The mutant transcript levels were assessed via qPCR and normalised to overall KCNQ1 transcript levels to assess the effect on splicing.

Results

For women and men, respectively, p.L353L alone conferred a 10.0 (p=0.064) ms and 14.0 (p=0.014) ms increase in QTc and in men only a significant interaction effect in combination with the p.V205M (34.6 ms, p=0.003) resulting in a QTc of ∼500 ms. The mechanism of p.L353L's effect was attributed to approximately threefold increase in exon 8 exclusion resulting in ∼25% mutant transcripts of the total KCNQ1 transcript levels.

Conclusions

Our results provide the first evidence that synonymous variants outside the canonical splice sites in KCNQ1 can alter splicing and clinically impact phenotype. Through this mechanism, we identified that p.L353L can precipitate QT prolongation by itself and produce a clinically relevant interactive effect in conjunction with other LQTS variants.

Keywords: long QT syndrome, exon skipping, <i>KCNQ1</i>, modifier, First Nations

Background

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) is characterised by a prolongation of the heart rate corrected QT interval (QTc) on 12-lead ECG and can predispose to syncope, seizures and sudden death if its trademark arrhythmia of torsades de pointes occurs.1 Tragically, sudden death may be the first manifestation. Approximately 80% of congenital LQTS is caused by mutations in at least 17 LQTS susceptibility genes which predominantly encode for either pore-forming ion channel subunits or channel-interacting proteins.2KCNQ1 encodes for the α-subunit of the slow delayed rectifier potassium channel, IKs (Kv7.1), and is the gene responsible for LQTS type 1 (LQTS1).3 To date, hundreds of KCNQ1 mutations have been identified, including missense, nonsense, canonical splice site, in-frame insertions/deletions and frameshift mutations. Incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity are well recognised within LQTS1 families.4–7 The genetic underpinnings for the heterogeneity in expressivity and penetrance largely remain unexplained.4,8

Although LQTS is relatively rare (1:2000),9 it is highly prevalent (∼1:125)10 in a remote Canadian First Nations community of 5500 people in northern British Columbia (the Gitxsan). Through community initiation, those diagnosed with LQTS and their relatives (∼800) have participated in our research which identified a novel c.613 G>A missense variant in KCNQ1. As previously described, this mutation results in a valine to methionine substitution at position 205 (p.V205M) in Kv7.1's S3 transmembrane region and negatively impacts IKs by slowing activation and accelerating deactivation.11 12 Besides the functional evidence for loss-of-function, a prolonged QTc segregates with p.V205M-positive status compared with variant-negative relatives and associated sudden cardiac death (SCD) further supports its designation as a LQTS1 pathogenic variant.10 11 Typical for LQTS, the phenotype is variable in this population, with some presenting earlier and more severely than others and sex differences in presentation have been noted. Although inherited LQTS traditionally has been considered to be a single gene disorder, evidence supports that the presentation is determined by additional genes and interactions with exogenous triggers, such as QT-prolonging drugs, physical activity and emotion. Indeed, LQTS is considered a model for complex inheritance.13 Therefore, this founder population provides a unique opportunity to identify genetic or environmental modifiers of disease in LQTS.

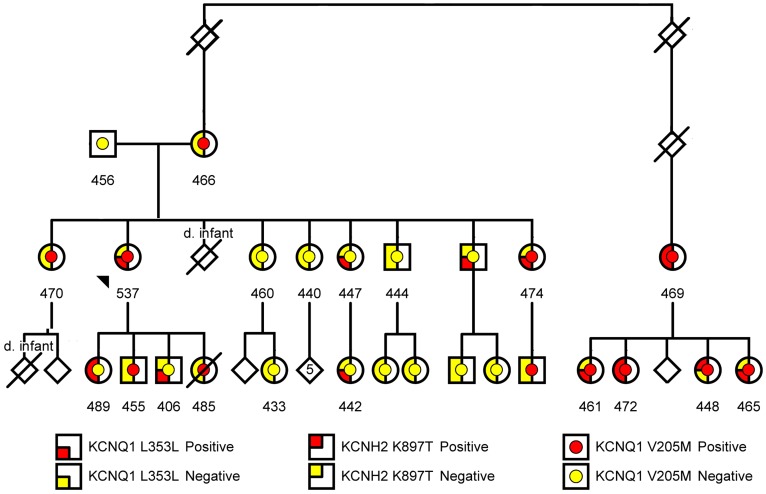

In 2004, sequencing of the most common genes causing LQTS in a First Nations index case (see figure 1) detected the p.V205M variant,11 along with a novel synonymous variant, a c.1059 G>A substitution in the KCNQ1 gene that maintains the original amino acid (Leucine) at position 353 (p. L353L). The significance of p.L353L was not clear, but it emerged again within the population when further molecular studies of the variable phenotype were initiated. Through pedigree analysis, p.L353L was confirmed to be inherited in trans to the p.V205M mutation. Population studies have confirmed the variant to be prevalent in the community, and to date, we have identified more than 70 adults with the p.L353L variant. This variant is not documented in Ensembl, dbSNP and ExAC.14 We sought to determine the underlying role of the p.L353L variant on the splicing of KCNQ1's exon 8, its potential QT-prolonging effect alone and as a genetic modifier in patients with p.V205M-mediated LQTS1.

Figure 1.

Pedigree of Family 1 harbouring the KCNQ1 p.V205M, p.L353L and KCNH2 p.K897T variants. The arrow indicates the proband. Note symbols representing the variant status and corrected QT (QTc) values (ms) below each participant.

Methods

Enrolment

As part of a larger study and in keeping with participatory methods,11 participants were invited to enrol if they had clinical features of LQTS or were related to an individual with a diagnosis of LQTS. Referrals for study entry were through affected family members and physicians. Community level approval was obtained as well as individual informed consent from all participants. Health information was documented upon enrolment through questionnaire and medical records to confirm clinical diagnosis or suspicion of LQTS. Chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, autoimmune disease, medications, alcohol use and street drug use were also recorded when possible.

Genetic analysis

Blood or saliva samples were collected and DNA was extracted and stored by standard methods and in keeping with DNA on Loan agreement with the community.15 Genotyping was carried out for the known KCNQ1 c.613 G>A (p.V205M) LQTS1-causing variant as previously described11 and for a second KCNQ1 known disease-causing variant (p.R591H) documented in an adjacent First Nations community10 in the BC Provincial Health Services Authority (PHSA) lab of the BC Children's Hospital, Vancouver. Expanded LQTS gene sequencing was carried out initially on five participants with a diagnosis of p.V205M-mediated LQTS1 and as well for another 37 participants with a borderline or increased QTc without the p.V205M mutation. The KCNQ1 p.L353L variant was observed in several of those who had expanded sequencing in this initial study, and the previously published and controversial KCNH2 p.K897T variant16–18 was also noted frequently. Genotyping for the KCNQ1 p.V205M, p.R591H, p.L353L and KCNH2 p.K897T variants was then carried out on all participants over the age of 16.

QTc determination

At enrolment, an ECG was performed and all other available 12-lead ECGs were collected from medical files and reviewed. Heart rate QTc measurements were assessed blinded to variant and clinical status on all available 12-lead ECGs. QT intervals were determined in all leads by the tangent method19 and the longest QT interval in any lead for an individual in any available ECG recording, corrected for rate, was considered the peak QTc.20 21 The peak QTc for each participant was recorded and used for analysis. Twelve hundred and sixty-nine manually read ECGs (mQTc) accounted for 61% of the eligible study population (257 persons). For those without mQTcs (162 persons), the Stata 13-IC program was used for the linear interpolation of mQTc on cQTcs (ECG computer calculated QTc) for the missing values of the mQTcs.

In silico splicing predictions

Four in silico predictive algorithms (Sroogle22 (http://sroogle.tau.ac.il/), ESEfinder23 (http://rulai.cshl.edu/cgi-bin/tools/ESE3/esefinder.cgi?process=home), RESCUE-ESE24 (http://genes.mit.edu/burgelab/rescue-ese/) and Human Splicing Finder25 (http://www.umd.be/HSF3/)) were used to predict the impact of the p.L353L on splicing regulatory motifs. All tools were used with default settings.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR

Total blood RNA was obtained with the PAXgene System (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) from three p.L353L-positive and two p.L353L-negative individuals from the First Nations population and one control from outside the First Nations population. cDNA was generated using the iScript Select cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Munich, Germany). Previously published primers26 were used to PCR amplify the KCNQ1 cDNA from exons 5 (5F: 5′-GGGCATCCGCTTCCTGCAGA forward) to 10 (10R: 5′-CATTGTCTTTGTCCAGCTTGAAC reverse) for gel electrophoresis. The relative levels of total KCNQ1 transcript were compared between p.L353L-positive and p.L353L-negative individuals using the comparative 2−ΔΔCt method where the samples were normalised to the total GAPDH levels using PrimeTime qPCR primers for GAPDH (Integrated DNA Technologies) and an exon 9 forward primer (9F: 5′CGCATGGAGGTGCTATGCT) and the exon 10 reverse primer for KCNQ1 levels. The previously validated forward primer spanning exon 7 and exon 9 boundaries (7.9F: 5′—CTTTGCGCTCCCAGCG/ACCG, ‘/’ indicates the exon boundaries) and exon 10 reverse primer was used for the selective amplification of the mutant transcript (Exon 7.9). A forward primer spanning the exon 8 and exon 9 boundaries (e8.9F: 5′CAGCCTCACTCATTCAG/ACCG) was used to assess the wild-type (WT) exon 8 splicing levels. Absolute transcript levels were assessed via a standard curve for each primer pair obtained using serial dilutions of a recombinant plasmid-containing cDNA. All RT-PCR experiments were run on an ABI PRISM 7900HT System (Applied Biosystems) using the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen). All samples were tested in triplicate. The transcript values were normalised to the total KCNQ1 transcript levels and were reported as mean±SD.

Statistical analysis

Unadjusted column statistics for average QTc were carried out separately for men and women in each mutation/variant category and for all those negative. Following preliminary descriptive analyses, linear regression (Ordinary Least Squares, OLS) was used to explore the relationship of the genetic variants on QTc. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were carried out considering the KCNQ1 p.V205M, KCNQ1 p.L353L, KCNH2 p.K897T variants independently, and in combination, adjusting for age, chronic disease (cardiovascular and autoimmune), past and current alcohol abuse and prescribed medications known to prolong the QT interval. An indicator variable was included to account for the potential influence of the interpolated QTc (1.96 and 3.26 ms in the female-adjusted and male-adjusted models, respectively). Akaike’s information criterion was used in model selection for best fit regarding the addition of the confounding factors. The analyses were run separately for men and women. Robust SEs (Huber–White sandwich estimate of variance) were applied to account for the borderline heteroscedasticity present in the model residuals.27 Bonferroni correction was performed on multiple pairwise testing adjusted for up to 28 comparisons (table 3). Stata 13-IC was used for all statistical analyses.

Table 3.

Adjusted predicted margins and multiple pairwise comparisons

| Variant status of participants | Sample size | Margin (QTc) | Delta-method SE |

Unadjusted groups | Bonferroni groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Men† | |||||

| Negative for all variants | 91 | 426.4 | 2.6 | A | A |

| L353L | 15 | 440.4 | 4.9 | B | AB |

| V205M | 21 | 455.8 | 4.1 | C | B |

| V205M*L353L | 5 | 504.4 | 9.1 | D | C |

| (B) Women‡ | |||||

| Negative for all variants | 169 | 448.4 | 1.9 | A | A |

| K897T | 18 | 444.0 | 5.7 | A | A |

| L353L | 40 | 458.1 | 4.9 | AB | AB |

| L353L*K897T | 3 | 483.2 | 10.0 | C | B |

| V205M | 40 | 479.2 | 5.1 | C | B |

| V205M*K897T | 3 | 447.5 | 2.6 | A | A |

| V205M*L353L | 7 | 474.5 | 12.2 | BC | AB |

| V205M*L353L*K897T | 2 | 459.0 | 4.0 | B | AB |

| (C) Men and women combined‡ | |||||

| Negative for all variants | 260 | 441.2 | 1.5 | A | A |

| K897T | 23 | 440.4 | 5.4 | AB | AB |

| L353L | 55 | 452.1 | 3.7 | BC | AB |

| L353L*K897T | 3 | 470.4 | 11.0 | CD | ABC |

| V205M | 61 | 470.5 | 3.6 | D | C |

| V205M*K897T | 3 | 443.1 | 2.9 | AB | AB |

| V205M*L353L | 12 | 488.8 | 11.0 | D | C |

| V205M*L353L*K897T | 2 | 455.0 | 3.8 | C | BC |

Margins sharing a letter in the group label are not significantly different at the 5% level.

*Adjusted for six comparisons' should be preceded by only 1 symbol (as seen above for men)

†Adjusted for six comparisons.

‡Adjusted for 28 comparisons.

QTc, corrected QT.

Incorporation of monomers encoded by full-length or mutant Kv7.1 into tetramers was modelled statistically using binomial distribution as previously described.28

Results

First Nations participants

Four hundred and forty-two adults above age 16 years (302 women and 140 men) were eligible for analysis. Four women homozygous for the p.V205M mutation and subjects of a previous publication were excluded.21 One man was excluded in all analyses as an outlier. This man was positive for both the KCNQ1 p.L353L variant and the KCNH2 p.K897T variant, but had been treated with arsenic trioxide, a chemotherapeutic agent which is also a potent QT-prolonging drug.29 To ensure the validity of our data, participants with other variants which might affect the phenotype, including the KCNQ1 p.R591H variant present in a nearby community,10 were omitted from our analysis. See table 1 for details of the genotypes of remaining participants (n=419) included in this study. There were 61 individuals positive for the KCNQ1 p.V205M mutation alone, 55 positive for the p.L353L variant alone and 23 positive for the KCNH2 p.K897T variant. In total, 12 persons were positive for the p.V205M mutation and the p.L353L variant, and 8 others had various combinations of the three genetic variants. Ninety-one men and 169 women were negative for all three variants.

Table 1.

Variant status of participants included in the regression analyses and their unadjusted average QTc

| Variant status | Men (n=137) |

Women (n=282) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| of participants (n=419) |

N | QTc (ms) Mean (SD) |

N | QTc (ms) Mean (SD) |

| Negative for all variants | 91 | 425.9 (29.3) | 169 | 447.8 (26.2) |

| V205M only | 21 | 457.0 (17.6) | 40 | 477.8 (30.3) |

| L353L only | 15 | 435.3 (19.6) | 40 | 461.7 (33.7) |

| K897T only | 5 | 430.9 (38.6) | 18 | 441.7 (24.7) |

| V205M*L353L | 5 | 520.1 (64.7) | 7 | 476.3 (31.3) |

| V205M*K897T | 0 | – | 3 | 451.0 (12.8) |

| L353L*K897T | 0 | – | 3 | 486.3 (5.5) |

| V205M*L353L*K897T | 0 | – | 2 | 470.5 (2.1) |

QTc, corrected QT.

QTc comparisons

Unadjusted mean QTc values with 95% CIs for those negative for all variants, positive for p.V205M, p.L353L, p.K897T each alone and combined p.V205M*p.L353L, p.L353L*p.K897T and p.V205M*p.L353L*p.K897T are shown in table 1.

Regression analyses

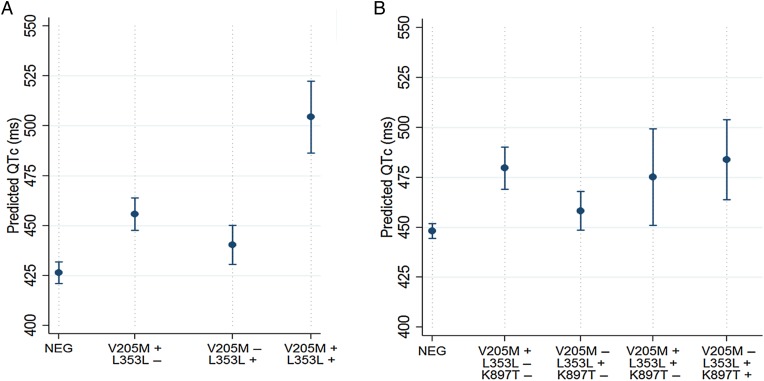

See table 2: For men (n=137), the reference (baseline) QTc was 418.4 ms when adjusted for age, alcohol use, QT-prolonging drug use and cardiovascular disease. The p.L353L variant alone increased the QTc by 14.0 ms (p=0.014, see table 2A), whereas the p.V205M mutation alone increased the QTc by 29.3 ms (p<0.001) above baseline. However, when the p.V205M*p.L353L variant combination was inherited, the QTc was predicted to increase by another 34.6 ms (p=0.003) above that dictated by each variant alone. When holding all variants at their mean QTc and controlling for the above covariates (also held at their mean), the predicted adjusted means demonstrate that those men with the combination of p.V205M*p.L353L variants will have a QTc approaching 500 ms (see figure 2A). This result was significantly different than for p.L353L or p.V205M variants alone (p<0.014, p<0.001, respectively) and for those with no documented variants. These results remained significant after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (see table 3A).

Table 2.

Adjusted regression analyses of all participants by sex

| Variable | Beta coefficient† | 95% CI‡ | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Men, interaction model, n=137, intercept=418.4 ms, adjusted R2=0.54 | |||

| V205M | 29.3 | 19.2 to 39.4 | <0.001 |

| L353L | 14.0 | 2.9 to 25.1 | 0.014 |

| K897T | 5.7 | −19.3 to 30.7 | 0.651 |

| V205M*L353L | 34.6 | 12.0 to 57.2 | 0.003 |

| L353L*K897T | – | ||

| V205M*K897T | – | ||

| V205M*L353L*K897T | – | ||

| (B) Women, interaction model, n=282, intercept=444.3 ms, adjusted R2=0.28 | |||

| V205M | 31.5 | 20.1 to 42.9 | <0.001 |

| L353L | 10.0 | −0.6 to 20.6 | 0.064 |

| K897T | −4.2 | −16.1 to 7.6 | 0.481 |

| V205M*L353L | −14.5 | −42.6 to 13.7 | 0.312 |

| V205M*K897T | −27.2 | −43.1 to -11.3 | 0.001 |

| L353L*K897T | 29.9 | 4.7 to 55.0 | 0.020 |

| V205M*L353L*K897T | −14.0 | −51.3 to 23.3 | 0.461 |

| (C) Men and women, interaction model, n=419, intercept=422.3 ms, adjusted R2=0.40 | |||

| V205M | 30.0 | 21.8 to 38.3 | <0.001 |

| L353L | 11.2 | 3.1 to 19.3 | 0.007 |

| K897T | −0.6 | −11.7 to 10.5 | 0.914 |

| V205M*L353L | 7.2 | −17.4 to 31.5 | 0.558 |

| V205M*K897T | −26.7 | −40.5 to −12.8 | <0.001 |

| L353L*K897T | 19.3 | −6.5 to 45.1 | 0.142 |

| V205M*L353L*K897T | −25.9 | −60.0 to 8.2 | 0.136 |

†Beta coefficients from OLS linear regression representing the baseline (intercept) and change in QTc (ms). Model was adjusted for age, past and current alcohol abuse, QT-prolonging drug use, cardiovascular disease and indicator variable for interpolated QTc.

‡95% CI using robust SEs.

QTc, corrected QT.

Figure 2.

(A) Adjusted predicted corrected QT (QTc) in interaction regression model in Men. Predicted effects of expected QTc in men with p.V205M and p.L353L variants above baseline QTc of 418.4 ms. (B) Adjusted predicted QTc in interaction regression model in women. Predicted effects of expected QTc in women with p.V205M, p.L353L and p.K879T above 444.3 ms. Both models were adjusted conditionally for age, cardiovascular diseases, past and current alcohol abuse and QT-prolonging drugs. The predicted QTc is shown on the Y-axis in ms and variant status on the X-axis.

For women, after adjustment for age and other covariates, the increase in QTc based on the p.L353L variant alone was 10.0 ms (p=0.064) and 31.5 ms (p<0.001) for the p.V205M mutation. In contrast to men, however, interaction of p.V205M*p.L353L did not show a statistically significant increase in QTc (see table 2B). However, the combination p.L353L*p.K897T conferred a positive effect (p=0.02) resulting in an increase of 29.9 ms from that expected with the p.L353L or the p.K897T alone. The predicted QTc associated with p.L353L*p.K897T at 483.2 ms (tables 2B and 3B) was significantly higher compared with those women without any documented genetic variants after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (28 comparisons). All individuals with the p.L353L*p.K897T variant combination underwent expanded LQTS gene sequencing (standard clinical LQTS sequencing30) with no other LQTS pathogenic variants detected. Table 2C presents the results when sexes were combined (n=419). Although the QTc effect of the p.V205M and p.L353L remains significant when inherited alone (p<0.001 and 0.007, respectively), there is no longer evidence of statistical significance for the p.V205M*p.L353L (p=0.558) as was seen with the male-only analysis. See supplemental data for figure of predicted margins (QTc) for all variant combinations.

jmedgenet-2016-104153supp001.pdf (193KB, pdf)

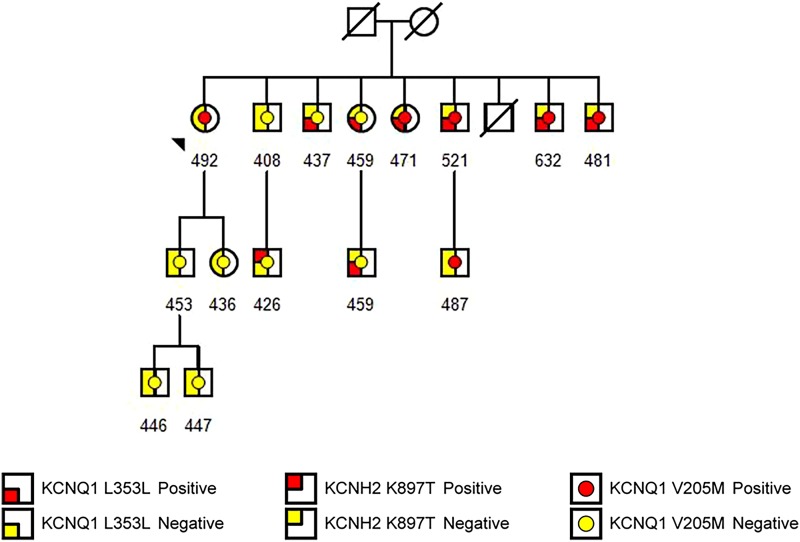

For family-based association of QTc with variants alone and in combination, see figures 1 and 3. Note in particular the p.V205M*L353L genotype in three men in figure 3 and the associated QTc in comparison with family members.

Figure 3.

Pedigree of Family 2 harbouring the KCNQ1 p.V205M, p.L353L and KCNH2 p.K897T variants. Note three male siblings with p.V205M*p.L353L and high corrected QT (QTc). The arrow indicates the proband. QTc values (ms) are listed below each participant.

In silico analysis

To determine if p.L353L could impact splicing, four in silico tools were used to determine if the variant may impact any predicted splicing regulatory elements. In support of the role of this variant on splicing, all four tools predicted exon splicing enhancer (ESE) motifs directly at the p.L353L position, and these sites were predicted to be disrupted by the synonymous nucleotide substitution (see table 4). Additionally, many of the tools predicted a change in the type of ESE from an alternative splicing factor /splicing factor 2 (ASF/SF2) ESE to a SRp40-binding site.

Table 4.

In silico analysis of the KCNQ1 c. 1059G>A (p.L353L) variant

| Algorithm tool used | Prediction performed by the tool | Interpretation of the KCNQ1 gene >ENST00000155840 transcript >exon number: 8, c.1059G>A variation |

|---|---|---|

| ESEfinder 3.0 | ESE finder for SRp40, SC35, SF2/ASF and SRp55 proteins | Identifies CTGAAGG as ESE. Predicts the G>A change in this motif to result in splicing regulatory protein binding from SF2/ASF to SRp40 |

| RESCUE-ESE 1.0 | ESE Hexamer finder | Identifies TGAAGG as ESE and predicts the G>A change resulting in enhancer motif sequence disruption |

| Human Splicing Finder | Combines 12 different algorithms to identify and predict mutations' effect on splicing motifs | Predicts the alteration of an exonic ESE site leading to potential alteration of splicing |

| Sroogle | Splicing regulatory sequences identifier | Predicts ESE motifs at the c.1059 position and predicts a loss of ESE site with the G>A change |

ESE, exon splicing enhancer.

Assessment of mutant transcript levels

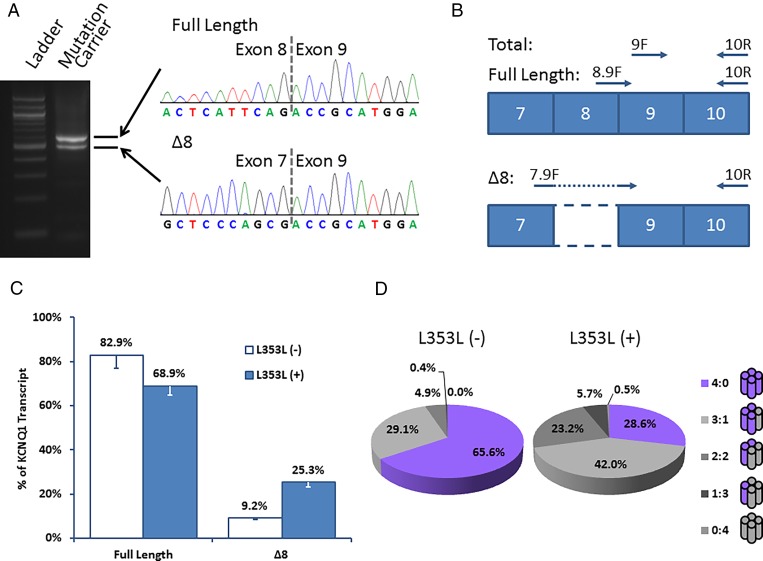

In order to identify alternatively spliced products, the lymphocyte mRNA-derived cDNA from the proband (see figure 1) was amplified using primers in exon 5 (5F) and exon 10 (10R). Two bands were identified, which correlated with full-length sequence and an alternatively spliced product that skipped exon 8 (annotated hereon as Δ8), which were assessed by direct sequencing (figure 4A). The contribution of the Δ8 transcript to the overall KCNQ1 transcript levels was assessed in three p.L353L-positive and two negative individuals from the First Nations population and one p.L353L-negative control from outside the First Nations. While the total relative KCNQ1 levels were indistinguishable between p.L353L-positive and p.L353L-negative individuals (p=0.69), the p.L353L-negative individuals (WT: 82.9±5.8%; Δ8: 9.2±0.6%) had significantly less skipping of exon 8 than p.L353L-positive individuals (WT: 68.9±4.2%, p=0.03; Δ8: 25.3±2.1%, p=0.003, figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Assessment of p.L353L mutant KCNQ1 transcript levels. (A) Gel electrophoresis (amplified using 5F and 10R primers) showing the full-length sequence and alternatively spliced product skipping exon 8 (Δ8). (B) Schematic of primers designed for the selective amplification of the Δ8 transcript (7.9F and 10R), the full-length transcript (8.9F and 10R) and total KCNQ1 transcript (9F and 10R). (C) Graph showing the percentage of KCNQ1 transcripts in p.L353L-positive versus p.L353L-negative individuals. (D) Chart and schematic of the statistical model fitted to a binomial distribution used to predict the likelihood of functional Kv7.1 tetramer formation. WT, wild-type.

This Δ8 transcript has been identified previously and shown to generate non-functional channels which exert a dominant-negative effect on WT channels.26 Given the increase in the Δ8 transcripts, statistical modelling fitted to a binomial distribution was used to predict the likelihood of functional Kv7.1 tetramer formation. The increase in Δ8 transcripts from 9.2% to 25.3% results in a 2.3-fold reduction in the likelihood of functional protein tetramer formation from 65.6% to 28.6% (figure 4D).

Discussion

Our study suggests that the KCNQ1 p.L353L synonymous variant impacts splicing efficiency resulting in the generation of alternatively spliced transcripts and ultimately decreasing functional tetramer formation. While it has a moderate independent effect on the QTc, it is unlikely to increase the QTc sufficiently to result in a LQTS phenotype alone. However, our results suggest a potential modifying and sometimes synergistic effect on the QTc when inherited with other variants.

LQTS as a complex condition

A prolonged QTc interval on 12-lead ECG (≥450 for men and ≥460 for women) is a marker of increased risk for arrhythmia and SCD10 31 and may be a result of genetic and/or non-genetic factors. Since the time the first LQTS gene (LQTS1) was mapped to 11p in 1992 (subsequently confirmed as KCNQ1), the variability in the phenotype has been highlighted.32 At that time, Vincent et al compared QTc values of those linked to the chromosome 11p15 locus (carriers) and their unlinked relatives (non-carriers), demonstrating that carriers had a significantly higher QTc. However, they also showed that there was an overlap in QTc values between carriers (range 410–590 ms) and non-carriers (380–470 ms) and not all carriers were symptomatic. Ongoing evaluation of LQTS cohorts and families has yielded consistent trends of variable clinical presentation.4 It is well established that a combination of mutations confers a more severe phenotype, with greater risk of SCD33 34 and common variants combined with mutations can modulate the overall effect on phenotype and the channel or channels involved.18 35–37 For example, the LQTS1 phenotype in a South African Founder population with the KCNQ1 p.A341V mutation was influenced by common variants in NOS1AP, a regulator of neuronal nitric oxide synthase.38 Since then, the effects of these NOS1AP variants on the QTc interval and clinical risk have been confirmed in a large heterogeneous LQTS cohort.39

Furthermore, numerous additional genomic regions (16q21 near NDRG4 and GINS3, 6q22 near PLN, 1p36 near RNF207, 16p13 near LITAF and 17q12 near LIG3 and RFFL), containing genes not previously recognised to be associated with LQTS, contribute to a prolonged QT interval in population-based cohort studies,40 41 each of which could impact on the QTc in conjunction with pathogenic variants. Little exploration, however, has been carried out on the potential impact of such variants on splicing, and in particular synonymous variants may be ignored, considered unlikely to be functional.

Splicing in disease

While synonymous variants are often dismissed as unlikely contributors to phenotype, increasingly their role in the pathogenesis of disease is being recognised.42 Even within LQTS, synonymous mutations have been recognised to cause disease. The hot spot mutation KCNQ1 A344A is the result of a c.1032G>A transition involving the terminal codon in exon 7.43 This synonymous mutation alters the 5′ splice site of intron 7 and leads to the skipping of exons 7 and 8.26 44 Several other splice site mutations situated in exon–intron junctions have been associated with LQTS with varying degrees of severity, including KCNQ1 c.477+1 G>A, inherited homozygously in a German family with LQTS and profound hearing loss,45 KCNQ1 c.1032+3 A>G resulting in skipping of exon 7 and a mild LQTS phenotype44 and KCNQ1 c.1251+1 G>A causing exon 9 skipping and a mild LQTS phenotype that triggered ventricular tachyarrhythmias during periods of hypokalaemia in a Japanese cohort.46 An intron-1 mutation c.387-5 T>A in KCNQ1 resulted in incomplete skipping of exon 2 with 10% of WT mRNA still expressed and homozygous individuals had a severe cardiac phenotype but no hearing loss.47 These mutations highlight the potential role of splicing in the pathogenesis of LQTS.

However, these LQTS1 causative mutations have all occurred at either the first or the last nucleotide of the exon or within the intron's canonical 5′ or 3′ splice sites. In contrast, this study has identified the first synonymous variant localising outside the terminal positions of the exon that exerts a role in disease pathogenesis. As p.L353L (c.1059G/A) is 27 nucleotides downstream of the start of the exon and 70 nucleotides upstream of the end of the exon, this is far outside of the critical 5′ and 3′ splice site motifs. The evidence presented within this study suggests that the p.L353L (c.1059G/A) nevertheless results in decreased recognition of exon 8 leading to increased dropping of this exon from the mature mRNA. Based on the in silico evidence, this likely is due to the disruption of the ASF/SF2 ESE or conversion of ASF/SF2 to a SRp40 ESE motif. There is evidence that while SRp40 acts primarily as an ESE, this is location dependent and thus SRp40 can also act as a strong to mild silencer of the splice site activity.48 In this previous study, the SRp40-binding site was moved along an exon of the ADAR2 gene, which has suboptimal splice efficiency, and at approximately the position SRp40 appears in the p.L353L mutant of KCNQ1, splice efficiency dropped. While we see that p.L353L disrupts splicing incompletely (by 24%), previous studies have also correlated a similar level of splicing disruption with a mild QT phenotype, suggesting that even small splice disruptions may contribute to disease.44

While splicing can be tissue specific, blood RNA has been used as a surrogate in the majority of the splicing mutations previously assessed in LQTS and was used in our experiments. The difference between p.L353L-positive and p.L353L-negative individuals suggests that the p.L353L variant has an impact on splicing, an effect likely recapitulated in the heart and shown clinically with an increase in QTc.

Sex differences

Women and men are well known to present differently in LQTS. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the sex difference, such as sex hormones which are believed to have both genomic and non-genomic effects on the QT interval. Oestrogen reduces repolarisation reserve in women and is therefore believed to be responsible for higher premenopausal susceptibility to drug-induced QT prolongation.49 Although our sample size of those with the combination p.V205M*p.L353L genotype is small (seven women and five men), the consistently higher increase in QTc in men, above that seen with p.V205M alone is not evident, on average, in the women with the same combination genotype. This finding is of interest in that mechanisms that affect the QTc in men disproportionately are rarely speculated on.50 However, male-specific effect has been observed in studies of modifying variants in LQTS1 populations, such as in the study by Lahtinen et al,51 where the presence of the variant p.D85N in KCNE1 was shown to modify the QT interval in men with LQTS1, but not in women. More recently, this phenomenon was observed in two additional Swedish founder populations with LQTS1 where QTc prolongation with NOS1AP variants was seen in men but not in women.52 Our results further support these observations that in certain circumstances men may be at higher risk, although the underlying mechanism is unclear.

Does the p.L353L destabilise the protective effect of KCNH2 p.K897T?

The effect of the KCNH2 p.K897T variant remains controversial in that it has been shown to confer both risk for18 36 and protection from17 a prolonged QTc. Our regression analysis in women suggests that the p.K897T variant likely lowers the QTc overall, consistent with other published reports.17 53 Also consistent with published reports suggesting the p.K897T may impair repolarisation if inherited with other variants,18 the combination of the p.L353L*p.K897T was associated with an increase in QTc compared with those negative for all variants. The resultant QTc effect clinically was indistinguishable from those with the pathogenic p.V205M variant alone (see figure 1 and table 3B). We were unable to assess this in men. More study is required to confirm this finding.

Conclusion

Our study provides the first evidence that synonymous variants outside the canonical splice sites in KCNQ1 can alter splicing and reduce WT transcript levels. The First Nations population which hosts a LQTS1 founder mutation (p.V205M) provided the unique opportunity to explore the effect of this distinctive splice variant on the QTc and the LQTS phenotype. We identified that p.L353L can affect the QT interval alone and may produce a synergistic effect in conjunction with other variants in certain circumstances. Sex-specific effects were observed, an emerging phenomenon reported in other LQTS1 Founder population studies.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge our continued partnership with the Gitxsan Health Society and extend our gratitude to the participants and local healthcare providers. JDK thanks the Mayo Clinic Medical Scientist Training Program for fostering an outstanding environment for physician–scientist training. We appreciate Beatrixe Whittome's assistance with data collection and figures and Sorcha Collins' assistance with final formatting. We appreciate Dr Jason D. Roberts’ assistance with ECG assessments.

Footnotes

Contributors: JDK was responsible for the data collection and laboratory analysis with regard to the L353L variant, wrote the first draft of the manuscript and contributed to subsequent drafts. AE developed the methods for the regression analysis and carried them out. SA contributed to literature review, created tables, figures and contributed to subsequent drafts of the manuscript. DJT contributed to the lab experiments and to the drafting of the manuscript. SM assisted in collection of clinical data and editing of final manuscript. CRK was responsible for the clinical cardiology phenotyping of adults and the QTc assessments. JM was the community partner responsible for review of the study, results and manuscript. AT contributed to the design of the study, funding and manuscript development. SS contributed to the design of the project and assisted in the development of the project and manuscript at all stages. LA conceived of the design of the clinical study, supervised the clinical data collection and analysis, contributed to editing of manuscripts and was responsible for funding of the project for the collection and genetic testing of the clinical cohort. MJA contributed to the funding, design of the laboratory experiments, assessment of results and drafting of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Windland Smith Rice Comprehensive Sudden Cardiac Death Program, Rochester, Minnesota (JDK, DJT, MJA). JDK is supported by a National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) National Research Service Awards (NRSA) Ruth L. Kirschstein individual predoctoral MD/PhD fellowship (F30HL127904) by the NIH grant GM72474-08. The clinical cohort work (LA, SA, AE, CRK, SS, AT) was funded through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Ottawa, Ontario, Research grant no. 81197 to LA and AT.

Competing interests: MJA is a consultant for Boston Scientific, Gilead Sciences, Medtronic and St. Jude Medical. MJA and Mayo Clinic receive royalties from Transgenomic for their FAMILION-LQTS and FAMILION-CPVT genetic tests. However, none of these commercial entities supported this research work.

Ethics approval: University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board, BC Northern Health Authority Research Ethics Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Schwartz PJ, Ackerman MJ. The long QT syndrome: a transatlantic clinical approach to diagnosis and therapy. Eur Heart J 2013;34:3109–16. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giudicessi JR, Ackerman MJ. Genotype- and phenotype-guided management of congenital long QT syndrome. Curr Probl Cardiol 2013;38:417–55. 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Q, Curran ME, Splawski I, Burn TC, Millholland JM, VanRaay TJ, Shen J, Timothy KW, Vincent GM, de Jager T, Schwartz PJ, Toubin JA, Moss AJ, Atkinson DL, Landes GM, Connors TD, Keating MT. Positional cloning of a novel potassium channel gene: KVLQT1 mutations cause cardiac arrhythmias. Nat Genet 1996;12:17–23. 10.1038/ng0196-17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Priori SG, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ. Low penetrance in the long-QT syndrome: clinical impact. Circulation 1999;99:529–33. 10.1161/01.CIR.99.4.529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moss AJ, Shimizu W, Wilde AAM, Towbin JA, Zareba W, Robinson JL, Qi M, Vincent GM, Ackerman MJ, Kaufman ES, Hofman N, Seth R, Kamakura S, Miyamoto Y, Goldenberg I, Andrews ML, McNitt S. Clinical aspects of type-1 long-QT syndrome by location, coding type, and biophysical function of mutations involving the KCNQ1 gene. Circulation 2007;115:2481–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.665406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barsheshet A, Goldenberg I, O-Uchi J, Moss AJ, Jons C, Shimizu W, Wilde AA, McNitt S, Peterson DR, Zareba W, Robinson JL, Ackerman MJ, Cypress M, Gray DA, Hofman N, Kanters JK, Kaufman ES, Platonov PG, Qi M, Towbin JA, Vincent GM, Lopes CM. Mutations in cytoplasmic loops of the KCNQ1 channel and the risk of life-threatening events: implications for mutation-specific response to β-blocker therapy in type 1 long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2012;125:1988–96. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.048041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amin AS, Giudicessi JR, Tijsen AJ, Spanjaart AM, Reckman YJ, Klemens CA, Tanck MW, Kapplinger JD, Hofman N, Sinner MF, Müller M, Wijnen WJ, Tan HL, Bezzina CR, Creemers EE, Wilde AAM, Ackerman MJ, Pinto YM. Variants in the 3′ untranslated region of the KCNQ1-encoded Kv7.1 potassium channel modify disease severity in patients with type 1 long QT syndrome in an allele-specific manner. Eur Heart J 2012;33:714–23. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Napolitano C, Novelli V, Francis MD, Priori SG. Genetic modulators of the phenotype in the long QT syndrome: state of the art and clinical impact. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2015;33:17–24. 10.1016/j.gde.2015.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz PJ, Stramba-Badiale M, Crotti L, Pedrazzini M, Besana A, Bosi G, Gabbarini F, Goulene K, Insolia R, Mannarino S, Mosca F, Nespoli L, Rimini A, Rosati E, Salice P, Spazzolini C. Prevalence of the congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2009;120:1761–7. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.863209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson H, Huisman LA, Sanatani S, Arbour LT. Long QT syndrome. CMAJ 2011;183:1272–5. 10.1503/cmaj.100138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arbour L, Rezazadeh S, Eldstrom J, Weget-Simms G, Rupps R, Dyer Z, Tibbits G, Accili E, Casey B, Kmetic A, Sanatani S, Fedida D. A KCNQ1 V205M missense mutation causes a high rate of long QT syndrome in a First Nations community of northern British Columbia: a community-based approach to understanding the impact. Genet Med 2008;10:545–50. doi:10.1097GIM.0b013e31817c6b19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eldstrom J, Wang Z, Werry D, Wong N, Fedida D. Microscopic mechanisms for long QT syndrome type 1 revealed by single-channel analysis of I(Ks) with S3 domain mutations in KCNQ1. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:386–94. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gargus JJ. Unraveling monogenic channelopathies and their implications for complex polygenic disease. Am J Hum Genet 2003;72:785–803. 10.1086/374317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, O'Donnell-Luria AH, Ware JS, Hill AJ, Cummings BB, Tukiainen T, Birnbaum DP, Kosmicki JA, Duncan LE, Estrada K, Zhao F, Zou J, Pierce-Hoffman E, Berghout J, Cooper DN, Deflaux N, DePristo M, Do R, Flannick J, Fromer M, Gauthier L, Goldstein J, Gupta N, Howrigan D, Kiezun A, Kurki MI, Moonshine AL, Natarajan P, Orozco L, Peloso GM, Poplin R, Rivas MA, Ruano-Rubio V, Rose SA, Ruderfer DM, Shakir K, Stenson PD, Stevens C, Thomas BP, Tiao G, Tusie-Luna MT, Weisburd B, Won H-H, Yu D, Altshuler DM, Ardissino D, Boehnke M, Danesh J, Donnelly S, Elosua R, Florez JC, Gabriel SB, Getz G, Glatt SJ, Hultman CM, Kathiresan S, Laakso M, McCarroll S, McCarthy MI, McGovern D, McPherson R, Neale BM, Palotie A, Purcell SM, Saleheen D, Scharf JM, Sklar P, Sullivan PF, Tuomilehto J, Tsuang MT, Watkins HC, Wilson JG, Daly MJ, MacArthur DG, Exome Aggregation Consortium. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016;536:285–91. 10.1038/nature19057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arbour L, Cook D. DNA on loan: issues to consider when carrying out genetic research with aboriginal families and communities. Community Genet 2006;9:153–60. 10.1159/000092651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marjamaa A, Newton-Cheh C, Porthan K, Reunanen A, Lahermo P, Väänänen H, Jula A, Karanko H, Swan H, Toivonen L, Nieminen MS, Viitasalo M, Peltonen L, Oikarinen L, Palotie A, Kontula K, Salomaa V. Common candidate gene variants are associated with QT interval duration in the general population. J Intern Med 2009;265:448–58. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02026.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, Chen S, Zhang L, Liu M, Redfearn S, Bryant RM, Oberti C, Vincent GM, Wang QK. Protective effect of KCNH2 single nucleotide polymorphism K897T in LQTS families and identification of novel KCNQ1 and KCNH2 mutations. BMC Med Genet 2008;9:87 10.1186/1471-2350-9-87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crotti L, Lundquist AL, Insolia R, Pedrazzini M, Ferrandi C, De Ferrari GM, Vicentini A, Yang P, Roden DM, George AL, Schwartz PJ. KCNH2-K897T is a genetic modifier of latent congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2005;112:1251–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.549071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Postema PG, De Jong JSSG, Van der Bilt IAC, Wilde AAM. Accurate electrocardiographic assessment of the QT interval: teach the tangent. Heart Rhythm 2008;5:1015–18. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rautaharju PM, Surawicz B, Gettes LS, Bailey JJ, Childers R, Deal BJ, Gorgels A, Hancock EW, Josephson M, Kligfield P, Kors JA, Macfarlane P, Mason JW, Mirvis DM, Okin P, Pahlm O, van Herpen G, Wagner GS, Wellens H, American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, American College of Cardiology Foundation, Heart Rhythm Society. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part IV: the ST segment, T and U waves, and the QT interval: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:982–91. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson HA, McIntosh S, Whittome B, Asuri S, Casey B, Kerr C, Tang A, Arbour LT. LQTS in Northern BC: homozygosity for KCNQ1 V205M presents with a more severe cardiac phenotype but with minimal impact on auditory function. Clin Genet 2014;86:85–90. 10.1111/cge.12235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz S, Hall E, Ast G. SROOGLE: webserver for integrative, user-friendly visualization of splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res 2009;37:W189–192. 10.1093/nar/gkp320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cartegni L, Wang J, Zhu Z, Zhang MQ, Krainer AR. ESEfinder: a web resource to identify exonic splicing enhancers. Nucleic Acids Res 2003;31: 3568–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fairbrother WG, Yeh RF, Sharp PA, Burge CB. Predictive identification of exonic splicing enhancers in human genes. Science 2002;297:1007–13. 10.1126/science.1073774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desmet FO, Hamroun D, Lalande M, Collod-Béroud G, Claustres M, Béroud C. Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res 2009;37:e67 10.1093/nar/gkp215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuji K, Akao M, Ishii TM, Ohno S, Makiyama T, Takenaka K, Doi T, Haruna Y, Yoshida H, Nakashima T, Kita T, Horie M. Mechanistic basis for the pathogenesis of long QT syndrome associated with a common splicing mutation in KCNQ1 gene. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2007;42:662–9. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 1980;48:817–38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsa E, Dixon JE, Medway C, Georgiou O, Patel MJ, Morgan K, Kemp PJ, Staniforth A, Mellor I, Denning C. Allele-specific RNA interference rescues the long-QT syndrome phenotype in human-induced pluripotency stem cell cardiomyocytes. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1078–87. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barbey JT, Pezzullo JC, Soignet SL. Effect of arsenic trioxide on QT interval in patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:3609–15. 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.GeneDx. Cardiology Genetics: Long QT Syndrome (LQTS) Panel. 2016. http://www.genedx.com/test-catalog/available-tests/lqts-gene-sequencing-deldup-panel/ (accessed 4 Oct 2016).

- 31.Roden DM. Keep the QT interval: it is a reliable predictor of ventricular arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm 2008;5:1213–15. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vincent GM, Timothy KW, Leppert M, Keating M. The spectrum of symptoms and QT intervals in carriers of the gene for the long-QT syndrome. N Engl J Med 1992;327:846–52. 10.1056/NEJM199209173271204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Itoh H, Shimizu W, Hayashi K, Yamagata K, Sakaguchi T, Ohno S, Makiyama T, Akao M, Ai T, Noda T, Miyazaki A, Miyamoto Y, Yamagishi M, Kamakura S, Horie M. Long QT syndrome with compound mutations is associated with a more severe phenotype: a Japanese multicenter study. Heart Rhythm 2010;7:1411–18. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilde AAM. Long QT syndrome: a double hit hurts more. Heart Rhythm 2010;7:1419–20. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nof E, Cordeiro JM, Pérez GJ, Scornik FS, Calloe K, Love B, Burashnikov E, Caceres G, Gunsburg M, Antzelevitch C. A common single nucleotide polymorphism can exacerbate long-QT type 2 syndrome leading to sudden infant death. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2010;3:199–206. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.898569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cordeiro JM, Perez GJ, Schmitt N, Pfeiffer R, Nesterenko VV, Burashnikov E, Veltmann C, Borggrefe M, Wolpert C, Schimpf R, Antzelevitch C. Overlapping LQT1 and LQT2 phenotype in a patient with long QT syndrome associated with loss-of-function variations in KCNQ1 and KCNH2. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2010;88:1181–90. 10.1139/Y10-094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Villiers CP, van der Merwe L, Crotti L, Goosen A, George AL, Schwartz PJ, Brink PA, Moolman-Smook JC, Corfield VA. AKAP9 is a genetic modifier of congenital long-QT syndrome type 1. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2014;7:599–606. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crotti L, Monti MC, Insolia R, Peljto A, Goosen A, Brink PA, Greenberg DA, Schwartz PJ, George AL. NOS1AP is a genetic modifier of the long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2009;120:1657–63. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.879643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomás M, Napolitano C, De Giuli L, Bloise R, Subirana I, Malovini A, Bellazzi R, Arking DE, Marban E, Chakravarti A, Spooner PM, Priori SG. Polymorphisms in the NOS1AP gene modulate QT interval duration and risk of arrhythmias in the long QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:2745–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newton-Cheh C, Eijgelsheim M, Rice KM, de Bakker PIW, Yin X, Estrada K, Bis JC, Marciante K, Rivadeneira F, Noseworthy PA, Sotoodehnia N, Smith NL, Rotter JI, Kors JA, Witteman JCM, Hofman A, Heckbert SR, O'Donnell CJ, Uitterlinden AG, Psaty BM, Lumley T, Larson MG, Stricker BHC. Common variants at ten loci influence QT interval duration in the QTGEN Study. Nat Genet 2009;41:399–406. 10.1038/ng.364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pfeufer A, Sanna S, Arking DE, Müller M, Gateva V, Fuchsberger C, Ehret GB, Orrú M, Pattaro C, Köttgen A, Perz S, Usala G, Barbalic M, Li M, Pütz B, Scuteri A, Prineas RJ, Sinner MF, Gieger C, Najjar SS, Kao WHL, Mühleisen TW, Dei M, Happle C, Möhlenkamp S, Crisponi L, Erbel R, Jöckel K-H, Naitza S, Steinbeck G, Marroni F, Hicks AA, Lakatta E, Müller-Myhsok B, Pramstaller PP, Wichmann H-E, Schlessinger D, Boerwinkle E, Meitinger T, Uda M, Coresh J, Kääb S, Abecasis GR, Chakravarti A. Common variants at ten loci modulate the QT interval duration in the QTSCD Study. Nat Genet 2009;41:407–14. 10.1038/ng.362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sauna ZE, Kimchi-Sarfaty C. Understanding the contribution of synonymous mutations to human disease. Nat Rev Genet 2011;12:683–91. 10.1038/nrg3051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murray A, Donger C, Fenske C, Spillman I, Richard P, Dong YB, Neyroud N, Chevalier P, Denjoy I, Carter N, Syrris P, Afzal AR, Patton MA, Guicheney P, Jeffery S. Splicing mutations in KCNQ1: a mutation hot spot at codon 344 that produces in frame transcripts. Circulation 1999;100:1077–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsuji-Wakisaka K, Akao M, Ishii TM, Ashihara T, Makiyama T, Ohno S, Toyoda F, Dochi K, Matsuura H, Horie M. Identification and functional characterization of KCNQ1 mutations around the exon 7-intron 7 junction affecting the splicing process. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011;1812:1452–9. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zehelein J, Kathoefer S, Khalil M, Alter M, Thomas D, Brockmeier K, Ulmer HE, Katus HA, Koenen M. Skipping of Exon 1 in the KCNQ1 gene causes Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome. J Biol Chem 2006;281:35397–403. 10.1074/jbc.M603433200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Imai M, Nakajima T, Kaneko Y, Niwamae N, Irie T, Ota M, Iijima T, Tange S, Kurabayashi M. Novel KCNQ1 splicing mutation in patients with forme fruste LQT1 aggravated by hypokalemia. J Cardiol 2014;64:121–6. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2013.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhuiyan ZA, Momenah TS, Amin AS, Al-Khadra AS, Alders M, Wilde AAM, Mannens MMAM. An intronic mutation leading to incomplete skipping of exon-2 in KCNQ1 rescues hearing in Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2008;98:319–27. 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2008.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goren A, Ram O, Amit M, Keren H, Lev-Maor G, Vig I, Pupko T, Ast G. Comparative analysis identifies exonic splicing regulatory sequences—the complex definition of enhancers and silencers. Mol Cell 2006;22:769–81. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li G, Cheng G, Wu J, Zhou X, Liu P, Sun C. Drug-induced long QT syndrome in women. Adv Ther 2013;30:793–802. 10.1007/s12325-013-0056-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moric-Janiszewska E, Głogowska-Ligus J, Paul-Samojedny M, Węglarz L, Markiewicz-Łoskot G, Szydłowski L. Age-and sex-dependent mRNA expression of KCNQ1 and HERG in patients with long QT syndrome type 1 and 2. Arch Med Sci 2011;7:941–7. 10.5114/aoms.2011.26604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lahtinen AM, Marjamaa A, Swan H, Kontula K. KCNE1 D85N polymorphism—a sex-specific modifier in type 1 long QT syndrome? BMC Med Genet 2011;12:11 10.1186/1471-2350-12-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winbo A, Stattin E, Westin I, Norberg A, Persson J, Jensen S, Rydberg A. NOS1AP variants affecting QTc in the long QT syndrome- mainly a Male affair? [Abstract]. San Francisco: Heart Rhythm Society Scientific Sessions, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bezzina CR, Verkerk AO, Busjahn A, Jeron A, Erdmann J, Koopmann TT, Bhuiyan ZA, Wilders R, Mannens MMAM, Tan HL, Luft FC, Schunkert H, Wilde AAM. A common polymorphism in KCNH2 (HERG) hastens cardiac repolarization. Cardiovasc Res 2003;59:27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jmedgenet-2016-104153supp001.pdf (193KB, pdf)