Abstract

The development of minimally invasive techniques allowed access to the necrotic cavity through transperitoneal, retroperitoneal, transmural and transpapillary routes. The choice of access to walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN) should depend not only on the spread of necrosis, but also on the experience of the clinical center. Herein we describe treatment of a patient with multilocular symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis using minimally invasive techniques. The single transmural access (single transluminal gateway technique – SGT) to the necrotic collection of the patient was ineffective. The second gastrocystostomy was performed using the same minimally invasive technique as an extra way of access to the necrosis (multiple transluminal gateway technique – MTGT). In the described case the performance of the new technique consisting in endoscopic multiplexing transmural access (MTGT) was effective enough and led to complete recovery of the patient.

Keywords: walled-off pancreatic necrosis, acute pancreatitis, endoscopic drainage, transmural drainage

Introduction

Acute necrotizing pancreatitis (ANP) appears in 5–10% of all incidents of acute pancreatitis and is often clinically manifested as a severe kind of disease [1]. In the course of ANP it leads to pancreatic parenchymal necrosis alone, peripancreatic necrosis alone or both structures at the same time (75–80% of cases of necrosis) [1, 2]. Acute necrotic collection (ANC) often occurs in the first 4 weeks of ANP and contains various amounts of liquefied necrosis and necrotic tissues [2, 3]. Walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN) is an ANC remaining after 4 weeks of disease and contains liquefied necrosis and necrotic tissues [2, 3]. Walled-off pancreatic necrosis unlike ANC is surrounded by a mature wall.

The main indications for interventional treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis are infection of the collection and clinical symptoms resulting from the fact of the collection’s presence (abdominal pain, jaundice as well as obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract) [4]. In the last three decades a change of strategy in interventional pancreatic necrosis treatment has been observed [4–9]. The development of minimally invasive techniques allowed access to the necrotic cavity through transperitoneal, retroperitoneal, transmural and transpapillary routes [7–13]. It was proved in randomized research that exploitation of minimally invasive methods in treatment of pancreatic necrosis significantly decreases the amount of complications and mortality compared to procedure of open necrosectomy [14].

The choice of access to the WOPN should depend not only on the spread of necrosis, but also on the experience of the clinical center. The single access to the necrotic collection is often insufficient in cases of infection of necrosis, and then combining several minimally invasive techniques (allowing multiple access to the necrosis) becomes an optimal strategy [4, 6]. The use of multiple access to the pancreatic necrosis using a minimally invasive technique is also possible. Widening of the access to the necrotic areas creates better drainage conditions and increases the efficiency of treatment [4, 6–8, 10, 11].

Herein we introduce a description of treatment of a patient with multilocular symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis using minimally invasive techniques. The single transmural access to the necrotic collection of the patient was inefficient. In the described case a second gastrocystostomy was performed using the same minimally invasive technique (endotherapy) as an extra way of access to the necrosis.

Case report

A 66-year-old male patient was admitted to the our department in May 2014 with pain of the abdomen accompanied with nausea. Laboratory blood tests performed at admission revealed increased levels of pancreatic enzymes (amylase 765 U/l; lipase 1436 U/l) as well as increased inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein (CRP) level 145 mg/l; leucocytosis 14 G/l). Severe acute pancreatitis of alcoholic etiology was diagnosed and conservative treatment was administered. An intensive liquid therapy was applied together with analgesic treatment and starvation diet. After 5 days enteral nutrition was initiated and continued for 15 days. Deterioration of general condition took place on the 7th day of hospitalization and was manifested by symptoms of multiorgan failure. Furthermore, fever up to 39°C appeared together with increased levels of inflammatory markers profiled in laboratory blood tests (CRP level 217 mg/l, leucocytosis 21 G/l). The blood culture proved negative. The features of acute pancreatitis with necrosis of the pancreatic body and tail were recognized in contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen. The same examination also confirmed necrosis of peripancreatic tissues running down the abdominal cavity up to the minor pelvis. Intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (piperacillin with tazobactam) was included empirically and continued for the next 14 days. The conservative treatment was continued with good clinical effect. Gradual improvement of the patient’s general condition was observed during the next days of hospitalization. Not only gradual liquidation, but also encapsulation of peripancreatic and pancreatic necrosis were proved by the next imaging examinations performed during hospitalization. Significantly, the mentioned examinations did not prove features of infection of the necrosis. Considering the improvement of general condition and the results of laboratory blood tests as well as observation of partial regression of necrotic areas in imaging examination the patient was discharged home after 4 weeks of hospitalization. The patient was left for further ambulatory observation. Due to the lack of symptoms from the presence of necrotic collections the patient was also left without interventional treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis (‘watchful waiting’ strategy).

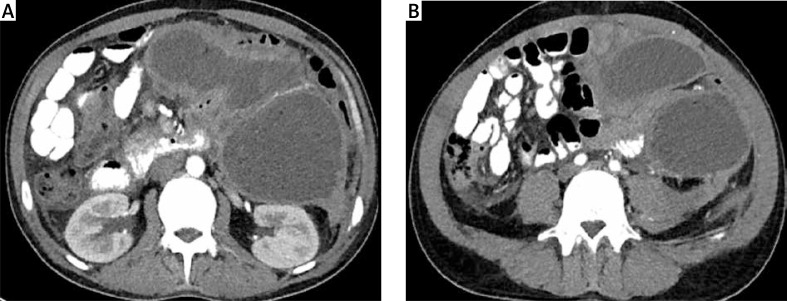

The patient was admitted to our department for an emergency procedure again in June 2014 due to symptoms of infected walled-off pancreatic necrosis. The patient complained of abdominal pain, which had lasted for a month, a fever of 38°C and loss of body weight (10 kg per month). Leukocytosis (18 G/l) together with a raised level of CRP (182 mg/l) was present in the laboratory blood tests. The performed blood culture was negative. The presence of three well-defined, pancreatic fluid collections with necrotic contents was revealed in contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen performed at admission (Photo 1). The first collection had a size of 74 × 64 × 36 mm and was positioned on the border of the body and tail of the pancreas. The second and third collections, which communicated with each other, were of size 110 × 98 × 86 mm and 89 × 74 × 68 mm and were located in the peripancreatic area.

Photo 1 A, B.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen performed before endoscopic treatment. Multilocular collection of walled-off pancreatic necrosis is clearly visible

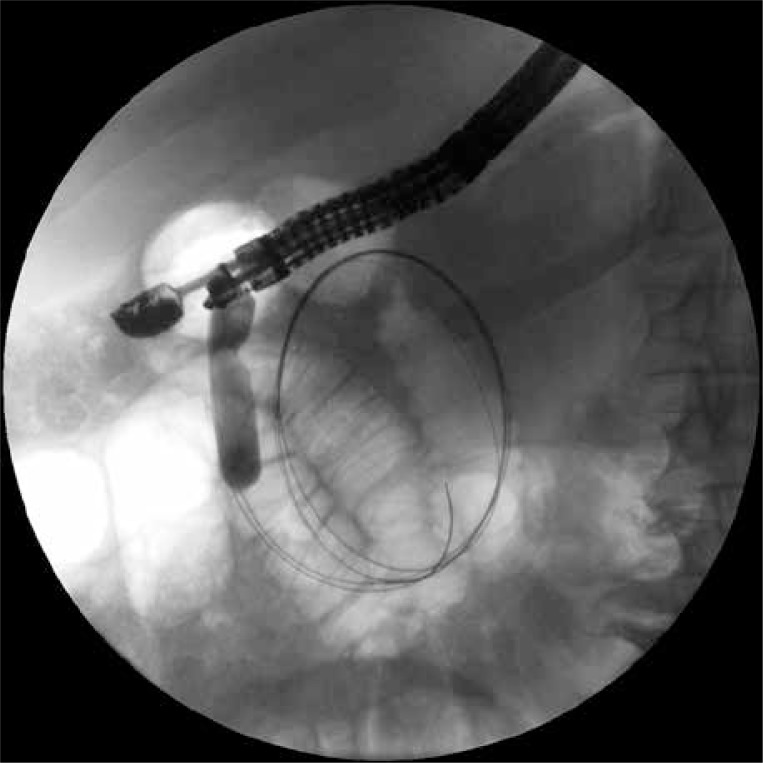

Endoscopic transmural drainage was performed during the time spent in the department. A stoma between the gastric lumen and the collection positioned at the border of the body and tail of the pancreas was created using a cystotome (Cystotome CST-10, Wilson-Cook, Ireland) and under control of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) (Pentax EG3870UTK, Japan). After execution of gastrocystostomy on the posterior wall of the gastric corpus an outflow of necrotic content through the stoma was observed. The gastrocystostomy was widened using a high-pressure balloon (Boston Scientific, USA) to the diameter of 15 mm (Photo 2). Thereafter two 7 Fr endoprostheses (Wilson-Cook, Ireland) and a 7 Fr nasal drain (Wilson-Cook, Ireland) were guided through the stoma into the lumen of the collection for irrigation purposes (active drainage – 200 ml saline solution per every 4 h).

Photo 2.

The first gastrocystostomy was performed during the first endoscopic procedure. The high-pressure balloon, with which the stoma was widened to the diameter of 15 mm, is visible on the fluoroscopic image. Two guidewires are also visible in the lumen of the necrotic collection

Performed culture of necrotic content revealed presence of Enterococcus faecalis as well as Enterococcus faecium. A targeted antibiotherapy (piperacillin with tazobactam) was applied for the period of 21 days.

The second endoscopic procedure was performed after 7 days of active drainage. Contrast applied through the nasal drain demonstrated partial regression of the drained necrotic collection. The fact that the remaining two walled-off collections held on despite the use of drainage was revealed on the endosonography image. The next gastropancreatic fistula was performed during the same procedure under EUS control in the antrum of the stomach (Photo 3). The outflow of dense, necrotic content was visible then. The fistula was widened using a high-pressure balloon (Boston Scientific, USA) of 20 mm diameter. Thereafter two 7 Fr endoprostheses were guided through the fistula (Photo 4). Their distal endings were left in the lumen of the necrotic collection (passive drainage).

Photo 3.

The second gastrocystostomy was executed during the next endoscopic procedure. Two guidewires inserted through the stoma into the necrotic area are visible in the fluoroscopy. Transmural stents guided through the first gastrocystostomy can be seen as well

Photo 4.

Multiple transluminal gateway technique. Transmural stents guided into walled-off pancreatic necrosis through two gastrocystostomies are visible

Improvement of the patient’s clinical condition occurred after 2 weeks of drainage. The fever retreated and the parameters of inflammation became normal. Regression of necrotic collections was revealed in CECT of the abdomen, which was performed after two weeks. The next (third) endoscopic procedure was performed after 17 days of active drainage. During this procedure an endoscopic retrograde pancreatography was executed in order to evaluate the morphology of the main pancreatic duct. The contrast applied through the major duodenal papilla filled the pancreatic duct, where in the area of the pancreatic body and tail the contrast leaked to the necrotic collection (Photo 5). Two pancreatic stents (Wilson-Cook, Ireland) were inserted transpapillary. The distal ends of the endoprostheses were left in the tail of the pancreas, bridging numerous partial disruptions of the main pancreatic duct (Photo 6).

Photo 5.

Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography. The applied contrast filled the pancreatic duct, which in the area of the pancreatic body and tail leaks to the collection of the walled-off pancreatic necrosis

Photo 6.

Multiple transluminal gateway technique. The transmural stents inserted into the walled-off pancreatic necrosis through two gastrocystostomies are visible as well as two pancreatic endoprostheses guided transpapillary

After 21 days of active drainage and observation of gradual regression of collections of WOPN it was decided to remove the nasal drain, leaving four transmural endoprostheses and two transpapillary pancreatic stents.

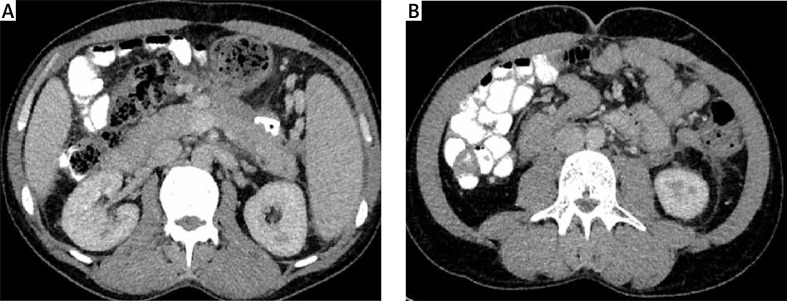

The control CECT was done in January 2015, which was 6 months after the end of the active drainage. The complete regression of WOPN (the diameter of collections did not exceed 30 mm) was confirmed then (Photo 7). During the performed endoscopic examination it was decided to remove transmural stents, due to the clinical condition and the results of radiological examination. The previously guided transpapillary pancreatic endoprostheses were also removed. What is more, the main pancreatic duct was contrasted and no leak into the peripancreatic area was observed. No new stents were inserted.

Photo 7 A, B.

Control contrast-enhanced computed tomography performed after the end of endoscopic treatment. Complete regression of multilocular walled-off pancreatic necrosis is evident

After 2 years of observation the patient is said to be in good general condition, without any symptoms. No new recurrence of collections was observed later on, during the next imaging examinations.

Discussion

The paper presents a description of treatment of a patient with severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis. The ‘watchful waiting’ strategy was used in the late phase of disease. The described strategy was unsuccessful, so the interventional treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis was necessary. Transmural endoscopic drainage of multilocular WOPN was performed.

Endoscopic, transmural drainage of walled-off pancreatic necrosis consists in complete removal of necrotic content though the fistula performed between the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract and the lumen of the necrotic collection [8, 15]. The first in the world endoscopic drainage of pancreatic necrosis was described nearly 20 years ago by Baron et al. [16]. Transmural fistula was performed in eleven patients suffering from WOPN, in whom the endoprosthesis and nasal drain were inserted through the stoma to the necrotic area [16]. The described method of treatment was named the single transluminal gateway technique (SGT) [16, 17]. Since that moment we have observed constant development of endoscopic treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis [8, 17–19]. The widening of the diameter of the fistula between the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract and the lumen of collection allowed insertion of the fiberoscope into the necrotic area and performance of endoscopic necrosectomy [20, 21]. Not only the diameter of the fistula was increased with the progress of endotherapy, but also the amount of transmural fistulas [22]. In 2011 Varadarajulu et al. introduced a new method of treatment (multiple transluminal gateway techniques – MTGT) consisting in performance of a few transmural fistulas between the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract and the lumen of the pancreatic necrosis [22]. The authors proved that application of a few (2–3) ways of transmural access to the pancreatic necrosis (MTGT) is more efficient than drainage with single transmural access [22]. According to the publication of Varadarajulu et al. the rate of successful treatment using this particular technique was 91.7% (11/12 patients) compared to the rate of successful treatment of 52.1% (25/48 patients) in the patients treated using transmural drainage from a single access (SGT) [22]. The same method of treatment (MTGT) was used in 2015 by Mukai et al. in 11 patients with WOPN [17]. Single transluminal gateway techniques were insufficient in the case presented by us. Only the creation of a second stoma (using MTGT) gave a beneficial, therapeutic effect and led to complete regression of WOPN in the described patient.

Percutaneous drainage used during the endoscopic treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis not only decreases the amount of endoscopic and radiological procedures, but also shortens the time of hospitalization and increases the efficiency of treatment of patients suffering from pancreatic necrosis [23]. In the present case there was no need to apply extra ways of access to the necrosis using other minimally invasive techniques. The success of treatment was achieved using endoscopic methods of treatment only. Performing two gastrocystostomies allowed access to extensive necrotic areas without the need to apply percutaneous drainage. To the best of our knowledge, development of endoscopic techniques in treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis has significantly reduced the use of other minimally invasive methods of treatment of WOPN. The high efficiency of endotherapy (including MTGT) has greatly decreased utilization of other ways of access to necrosis.

The greater the diameter of the stoma between the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract and the lumen of the necrotic collection is, the greater is the efficiency of drainage [15, 18], particularly with the use of self-expandable metal stents (SEMS), which provide an appropriate diameter of the stoma [24]. It seems that application of SEMS during transmural drainage should increase the efficiency of treatment and shorten the time of endotherapy of WOPN. Bang et al. presented application of the MTGT technique with use of an AXIOS stent [25]. Perhaps the use of a transmural self-expandable, metal stent would have shortened the time of treatment in the present patient; however, the drainage using two transmural stomata (MTGT) and plastic stents proved equally efficient in treatment of extensive necrotic areas.

Conclusions

In the present case we found that multiple transluminal gateway techniques are an efficient method of treatment in patients with extensive, multilocular necrotic collections. Use of MTGT requires no extra ways of access to the necrosis. What is more, we proved not only that endotherapy represents an alternative to other minimally invasive techniques of treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis, but also that it can be effective as the only method of treatment in selected patients.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Sakorafas GH, Tsiotos GG, Sarr MG. Extrapancreatic necrotizing pancreatitis with viable pancreas: a previously under-appreciated entity. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:643–8. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thoeni RF. The revised Atlanta classification of acute pancreatitis: its importance for the radiologist and its effect on treatment. Radiology. 2012;262:751–64. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis – 2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102–11. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman ML, Werner J, van Santvoort HC, et al. Interventions for necrotizing pancreatitis: summary of a multidisciplinary consensus conference. Pancreas. 2012;41:1176–94. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318269c660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bello B, Matthews JB. Minimally invasive treatment of pancreatic necrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6829–35. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i46.6829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.da Costa DW, Boerma D, van Santvoort HC, et al. Staged multidisciplinary step-up management for necrotizing pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2014;101:e65–79. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szeliga J, Jackowski M. Minimally invasive procedures in severe acute pancreatitis treatment – assessment of benefits and possibilities of use. Videosurgery Miniinv. 2014;9:170–8. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2014.41628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smoczyński M, Jagielski M, Jabłońska A, Adrych K. Endoscopic necrosectomy under fluoroscopic guidance – a single center experience. Videosurgery Miniinv. 2015;10:237–43. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2015.52058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smoczyński M, Jagielski M, Jabłońska A, Adrych K. Transpapillary drainage of walled-off pancreatic necrosis – a single center experience. Videosurgery Miniinv. 2015;10:527–33. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2015.55677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loveday BP, Mittal A, Phillips A, et al. Minimally invasive management of pancreatic abscess, pseudocyst, and necrosis: a systematic review of current guidelines. World J Surg. 2008;32:2383–94. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9701-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loveday BP, Petrov MS, Connor S, et al. A comprehensive classification of invasive procedures for treating the local complications of acute pancreatitis based on visualization, route, and purpose. Pancreatology. 2011;11:406–13. doi: 10.1159/000328191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wysocki Ł, Wroński M, Cebulski W, et al. Combined minimally invasive management of infected pancreatic necrosis: a case report. Videosurgery Miniinv. 2014;9:107–9. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2014.40989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jagielski M, Smoczyński M, Adrych K. Transpapillary drainage of pancreatic parenchymal necrosis. Videosurgery Miniinv. 2015;10:491–4. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2015.54075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, et al. Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baron TH, Kozarek RA. Endotherapy for organized pancreatic necrosis: perspectives after 20 years. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1202–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baron TH, Thaggard WG, Morgan DE, Stanley RJ. Endoscopic therapy for organized pancreatic necrosis. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:755–64. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8780582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukai S, Itoi T, Sofuni A, et al. Expanding endoscopic interventions for pancreatic pseudocyst and walled-off necrosis. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:211–20. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-0957-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papachristou GI, Takahashi N, Chahal P, et al. Peroral endoscopic drainage/debridement of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Ann Surg. 2007;245:943–51. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000254366.19366.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smoczyński M, Marek I, Dubowik M, et al. Endoscopic drainage/debridement of walled-off pancreatic necrosis – single center experience of 112 cases. Pancreatology. 2014;14:137–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seifert H, Wehrmann T, Schmitt T, et al. Retroperitoneal endoscopic debridement for infected peripancreatic necrosis. Lancet. 2000;356:653–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02611-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seifert H, Biermer M, Schmitt W, et al. Transluminal endoscopic necrosectomy after acute pancreatitis: a multicentre study with long-term follow-up (the GEPARD Study) Gut. 2009;58:1260–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.163733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varadarajulu S, Phadnis MA, Christein JD, Wilcox CM. Multiple transluminal gateway technique for EUS-guided drainage of symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.03.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ross A, Gluck M, Irani S, et al. Combined endoscopic and percutaneous drainage of organized pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bang JY, Hawes R, Bartolucci A, Varadarajulu S. Efficacy of metal and plastic stents for transmural drainage of pancreatic fluid collections: a systematic review. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:486–98. doi: 10.1111/den.12418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bang JY, Varadarajulu S. Management of walled-off necrosis using the multiple transluminal gateway technique with the Hot AXIOS System. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:103. doi: 10.1111/den.12557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]