Abstract

Background

We examined activity-specific patterns and child, family, and environmental correlates of participation restriction in nine community-based activities among preschoolers with disabilities who have received Part C early intervention services.

Methods

Data were gathered from a subsample of 1509 caregivers whose children (mean age = 67.7 months) had enrolled in the National Early Intervention Longitudinal Study (NEILS) and completed a 40-minute computerized telephone interview or 12-page mailed survey. Data were analyzed on cases with complete data on the variables of interest. Bivariate relationships were examined between variables, including patterns of co-reporting participation difficulties for pairs of community activities.

Results

Caregivers were more than twice as likely to report difficulty in 1 activity (20%) than difficulties in 2–3, 4–5, or 6–9 activities. Co-reporting paired difficulties was strong for activities pertaining to neighborhood outings but less conclusive for community-sponsored activities and recreation and leisure activities. Our data show strong and positive associations between child functional limitations in mobility, toileting, feeding, speech, safety awareness, and friendships and participation difficulty in 7 to 9 activities. Lower household income was associated with participation difficulty in 7 out of 9 activities and difficulty managing problematic behavior was strongly associated with participation difficulty in all 9 activities. Each of the 3 environmental variables (limited access to social support, transportation, and respite) was associated with participation restrictions in all 9 activities.

Conclusion

Results provide practitioners with detailed descriptive knowledge about modifiable factors related to the child, family, and environment for promoting young children’s community participation, as well information to support development of a comprehensive assessment tool for research and intervention planning to promote community participation for children enrolled in early intervention.

Keywords: participation, environment, community, preschoolers

The foundation for lifelong health is laid during the early years of a child’s life through positive experiences in supportive environments (National Research Council, 2004). When caregivers and communities support young children to participate in activities that they need and want to do, children have increased opportunities to experience health and well-being (Law, 2002) and to develop knowledge, skills, and relationships that are purposeful and culturally valued (Dunst, 2001; Weisner, 2002; Rogoff, 2003). Caregivers of young children with disabilities are likely to be situated in environments with multiple stressors and few supports leading to greater risk of experiencing participation difficulty and need for intervention support (Maul & Singer, 2009; Simeonsson, 1991). For this reason, participation is one of four major goals for children 0–3 years with, or at risk for, disabilities and who are made eligible for early intervention services (PL 108–446) in the United States through Part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

Despite its importance, less than 2.0% of Part C early intervention service plans make reference to goals that address the young child’s participation in home or community activities (Dunst et al., 1998). One reason for this gap is that service providers are not equipped with adequate knowledge or tools about the characteristics of children and families and/or environmental factors that restrict a young child’s participation in specific settings and activities to identify appropriate targets for intervention on this outcome. Contemporary models of best practice for early intervention (Guralnick, 2005; Fox & Hemmeter, 2009) do not provide detailed guidelines for addressing the goal of participation in practice. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF-CY; WHO, 2007) provides a framework for understanding personal factors (child personal factors, family demographic factors) and environmental factors that influence participation among children and youth. Research evidence on factors with direct and indirect effects on children’s participation have been identified and include (1) child personal factors such as the child’s age (Dunst, et al., 2002), gender (Fabes, et al., 2003); (2) the child’s functional abilities (Bar-Haim & Bart, 2006); (3) family factors such as parental education, household income, and parental beliefs (King, et al., 2003; King, et al., 2006); and (4) environmental resources including social support, transportation, behavior management, and respite (Khetani, Orsmond, et al., 2011). However, little is known about the subset of these factors associated with participation difficulty between/across specific activities (e.g., mall, park, movie). There is need to build detailed knowledge so that service providers do not oversimplify the problem when addressing the outcome of participation in practice.

Comprehensive and detailed knowledge about patterns and predictors of young children’s participation is expected to develop rapidly with the emergence of new measures of participation and environment. LaVesser & Berg (2011) detected activity-specific participation patterns among young children with an ASD using the Preschool Activity Card Sort (PACS), a semi-structured interview that combines assessment of participation and environment for children 3–6 years old. To our knowledge, there is no survey instrument that includes a comprehensive set of home and community activities, combines assessment of participation and environment, covers the 0–5 age range, and is suitable for use in Part C service planning and large-scale research (Bedell et al., 2012; Khetani et al, 2012; Khetani & Coster, in press).

For this study, we leveraged data from the National Early Intervention Longitudinal Study (NEILS; 1997–2007) to finalize the design of the Young Children’s Participation and Environment Measure (YC-PEM), a caregiver-report survey that we are developing for use in service-planning and large-scale research involving children 0–5 years. The YC-PEM is modeled after the Participation and Environment Measure for Children and Youth (PEM-CY) (Coster et al, 2010) in that assessment of participation and environment are combined in a single measure to afford for closer examination of environmental supports and barriers to participation in the home and community settings. Decisions about age-appropriate content and scaling for the YC-PEM have been informed by parents’ perspectives about 1) the broad range of important activities in which young children participate, 2) ways of appraising young children’s participation, and 3) child, family, and environmental factors and parent strategies for promoting young children’s participation (Bernheimer & Keogh, 1995; Dunst, et al., 2002; Khetani, Cohn, et al., 2011; Khetani, Orsmond, et al., 2012). Key decisions about survey content for the community section of the YC-PEM will be validated prior to large-scale validation by answering three questions from caregivers of preschoolers with disabilities:

What is the prevalence of perceived participation difficulty in three types of community activities: neighborhood outings, community-sponsored events, and recreation and leisure?

Among caregivers who perceive more than one area of participation difficulty, are there logical patterns of co-reporting within each of the three types of community-based activities?

What child, family, and environmental factors are associated with perceived difficulty participating in community-based activities?

Methods

Study Sample

Caregivers of children residing in one of 20 states were initially recruited to participate in the National Early Intervention Longitudinal Study (NEILS) (1997–2007). NEILS was the first national study of Part C of IDEA early intervention services for infants and toddlers with disabilities and their caregivers and families. Data collected followed a large sample of children from participation in early intervention services until kindergarten (SRI, 2012). Together, these caregivers were selected to represent the state-to-state variation in service format (e.g., criteria used to define developmental delay) and focus (e.g., whether the state served children with a documented risk for developmental delay). An initial sample of 3,338 caregivers enrolled in the NEILS study based on the following eligibility criteria: (1) parental consent, (2) the child was younger than 31 months old when the Individualized Family Service Plan was developed, (3) the respondent spoke English or Spanish, and (4) only one child was being recruited for the study (no sibling receiving Part C early intervention services). The current study used a subsample of 1509 caregivers with complete data on the variables of interest.

Study Variables

The NEILS study involved gathering information about child and family outcomes. For this study, data on the study outcomes were derived through a 40-minute computerized interview or 12-page mailed survey completed by a caregiver when their child entered kindergarten. Each caregiver was asked the following question in reference to 8 community-based activities: Compared to other families with children that are your child’s age, is it difficult for your family to do the following activities because of your child (yes, no)? Caregivers also rated the extent to which they had chances to take part in religious, social, and civic events in the community, on a 4-point scale (strongly agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree).

We selected child factors (4 personal factors and 9 functional abilities), family factors (n=4), and environmental factors (n=3) that captured a range of factors that have been described in the peer-reviewed literature as influencing young children’s participation in community activities. Data on these factors were obtained either when the child enrolled in Part C services or when the child entered kindergarten. After deleting missing data, a total of 1509 families with complete data pertaining to 20 independent and 8 dichotomous outcome variables were identified. We dichotomized the 9th outcome variable related to religious, social, and civic events (strongly agree and agree vs. disagree and strongly disagree). We then sorted the nine dichotomous outcome variables into one of the following three categories as they appear on the current version of the YC-PEM: 1) neighborhood outings (mall/store, grocery, restaurant), 2) community-sponsored activities (movie, event, worship, library), and 3) recreation and leisure activities (vacation, park) (Dunst et al., 2002; Khetani, Cohn, et al., 2011). Due to insufficient sample distribution for stratification and comparisons by outcomes, we recoded 13 study variables by collapsing response options. See appendix for item descriptions, original response options, and recoding of each study variable.

Data Analysis

To examine community participation patterns of our study sample (research questions 1 and 2), we first summed the number of activities in which each caregiver reported participation difficulties to create global participation burden scores. The distribution of these scores (range: 0 to 9) was then tabulated to assess the prevalence of participation difficulty by calculating the percentage of respondents experiencing cumulative participation burden. Next, we looked at co-occurrence (co-reporting) of participation difficulty for all possible pairs of the nine community-based activities to explore potential patterns among related activities. Bivariate associations were evaluated using Phi (ϕ) coefficients. Cohen’s criteria (1988) were used to categorize the relative strengths of the associations: < 0.3 = weak, ≥ 0.3 to < 0.5 = moderate, and ≥ 0.5 = strong association. To examine child, family, and environmental factors associated with caregiver perceptions of participation difficulty (research question 3), descriptive summaries (frequencies and percentages) of caregiver responses were tabulated for each of the nine community-based activity questions. Responses from each of nine outcomes were then cross-tabulated with our selected list of child-, family-, and environment-related variables. Chi-square tests were used to assess the bivariate associations between the various child, family, and environmental characteristics and caregiver perceptions of difficulty participating in the nine community-based activities. Given the large number of comparisons and increased probability of committing a Type I error, alpha was set at .01 and we further controlled for the false discovery rate using the modified Bonferroni-type procedure developed by Benjamini and Hochberg (1995). Standardized residuals were also calculated to assess the relative contribution of different levels of a given categorical variable to the observed association; absolute value > 2 was considered statistically significant (Portney & Watkins, 2009). All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 20.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) and results are presented on the subsample using unweighted data.

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 1509 caregivers reported on children between 56–86 months of age (mean = 67.7 months). A majority of the children were Caucasian (60.0%), male (61.9%), and eligible for Part C services due to developmental delay (63.6%). Approximately half of respondents (49.8%) had earned a college or vocational degree. Children on average resided in 4-person households, and 58.4% of caregivers reported earning $50,000 or less per year. Complete sample characteristics for child-, family-, and environment-level variables are provided in the second column of Tables 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

Table 2.

Parent Perceptions of Participation Difficulty in Community Activities According to Child-Related Factors

| Child Factors | N | Neighborhood Outings (%)

|

Community-sponsored Activities (%)

|

Recreation & Leisure (%)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mall/store | Grocery | Restaurant | Movie | Event | Worship | Library | Vacation | Park | ||

| Total | 1,509 | 13.5 | 10.5 | 11.1 | 13.9 | 27.5 | 11.7 | 11.4 | 10.0 | 4.8 |

| Age | * | * | ||||||||

| 56–65 months | 523 | 11.3 | 8.8 | 8.8 | 10.5 | 25.2 | 9.0 | 10.3 | 8.6 | 3.1 |

| 66–78 months | 943 | 14.2 | 10.7 | 11.8 | 15.3 | 28.6 | 12.8 | 11.6 | 10.3 | 5.7 |

| 79–86 months | 43 | 25.6 | 25.6 | 23.3 | 25.6 | 30.2 | 20.9 | 20.9 | 20.9 | 4.7 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 934 | 13.6 | 10.9 | 11.2 | 14.2 | 28.1 | 13.0 | 12.3 | 10.7 | 5.0 |

| Female | 575 | 13.4 | 9.7 | 10.8 | 13.4 | 26.6 | 9.7 | 9.9 | 8.9 | 4.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | * | |||||||||

| White | 905 | 12.4 | 9.3 | 10.2 | 12.6 | 21.1 | 10.6 | 9.7 | 9.2 | 3.5 |

| Black | 238 | 13.4 | 11.8 | 10.1 | 12.2 | 31.1 | 12.2 | 15.1 | 12.6 | 8.0 |

| Hispanic | 235 | 19.1 | 14.5 | 15.7 | 17.9 | 46.4 | 15.3 | 15.7 | 11.1 | 6.4 |

| Other | 129 | 11.6 | 9.3 | 10.9 | 19.4 | 31.0 | 12.4 | 8.5 | 9.3 | 4.7 |

| Eligibility | ||||||||||

| Delay | 960 | 14.5 | 11.6 | 12.3 | 13.4 | 28.3 | 12.1 | 11.8 | 10.3 | 4.5 |

| Diagnosis | 320 | 12.2 | 10.3 | 9.4 | 15.3 | 25.3 | 10.9 | 12.8 | 9.7 | 6.3 |

| At risk | 229 | 11.4 | 6.1 | 8.3 | 14.0 | 27.1 | 11.4 | 7.9 | 9.2 | 3.9 |

| Move Arms/hands | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||

| Not well | 274 | 23.0 | 17.9 | 14.6 | 21.9 | 28.1 | 17.5 | 18.2 | 17.5 | 8.0 |

| Well | 1,235 | 11.4 | 8.8 | 10.3 | 12.1 | 27.4 | 10.4 | 9.9 | 8.3 | 4.0 |

| Move Legs/feet | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| Not well | 261 | 26.1 | 21.8 | 19.5 | 24.5 | 32.6 | 19.5 | 18.8 | 20.3 | 11.5 |

| Well | 1,248 | 10.9 | 8.1 | 9.3 | 11.7 | 26.4 | 10.1 | 9.9 | 7.9 | 3.4 |

| Speech | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Very easy | 620 | 7.7 | 4.8 | 6.1 | 6.6 | 25.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 3.5 |

| Fairly easy | 456 | 11.4 | 9.9 | 10.7 | 12.3 | 23.5 | 11.4 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 3.5 |

| Not easy | 433 | 24.0 | 19.2 | 18.5 | 26.1 | 34.2 | 19.2 | 20.1 | 15.2 | 7.9 |

| Spoon | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Not well | 208 | 29.3 | 25.0 | 26.9 | 35.6 | 46.2 | 28.4 | 27.4 | 25.0 | 12.5 |

| Well | 1,301 | 11.0 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 10.5 | 24.5 | 9.1 | 8.8 | 7.6 | 3.5 |

| Cup | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Not well | 66 | 34.8 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 47.0 | 43.9 | 30.3 | 25.8 | 28.8 | 13.6 |

| Well | 1,443 | 12.5 | 9.4 | 10.0 | 12.4 | 26.7 | 10.9 | 10.7 | 9.1 | 4.4 |

| Bladder | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| Not well | 160 | 35.0 | 31.9 | 34.4 | 40.0 | 36.3 | 33.1 | 30.6 | 28.1 | 16.9 |

| Well | 1,349 | 11.0 | 7.9 | 8.3 | 10.8 | 26.5 | 9.2 | 9.1 | 7.9 | 3.3 |

| Bowel | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Not well | 158 | 36.1 | 31.6 | 33.5 | 39.2 | 40.5 | 32.9 | 28.5 | 25.9 | 15.2 |

| Well | 1,351 | 10.9 | 8.0 | 8.4 | 11.0 | 26.0 | 9.3 | 9.4 | 8.1 | 3.6 |

| Avoids Danger | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Not well | 315 | 35.9 | 28.6 | 29.8 | 34.3 | 40.6 | 33.0 | 30.5 | 25.4 | 10.2 |

| Well | 1,194 | 7.6 | 5.7 | 6.1 | 8.5 | 24.0 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 5.9 | 3.4 |

| Friendships | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| No Trouble | 381 | 29.1 | 21.8 | 25.7 | 31.5 | 39.9 | 28.1 | 28.3 | 21.8 | 10.0 |

| Has trouble | 1,128 | 8.2 | 6.6 | 6.1 | 8.0 | 23.3 | 6.2 | 5.7 | 6.0 | 3.0 |

Cell values are row percentages showing the proportion of respondents who reported yes to experiencing difficulty with the specified community activity.

indicates p < .0069, which is the significance threshold obtained from adjusting for the false discovery rate across all comparisons in Tables 2–4 with an initial alpha = .01.

Bold indicates |standardized residual| > 2.

Table 3.

Parent Perceptions of Participation Difficulty in Community Activities According to Family-Related Factors

| Family Factors | N | Neighborhood Outings (%)

|

Community-sponsored Activities (%)

|

Recreation & Leisure (%)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mall/store | Grocery | Restaurant | Movie | Event | Worship | Library | Vacation | Park | ||

| Total | 1,509 | 13.5 | 10.5 | 11.1 | 13.9 | 27.5 | 11.7 | 11.4 | 10.0 | 4.8 |

| Respondent education | * | |||||||||

| Less than HS | 107 | 18.7 | 15.9 | 18.7 | 17.8 | 50.5 | 15.9 | 16.8 | 13.1 | 8.4 |

| HS diploma/GED | 392 | 14.5 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 13.5 | 32.1 | 13.8 | 11.5 | 10.7 | 5.4 |

| Some college/vocational | 259 | 14.3 | 12.0 | 11.6 | 18.1 | 30.5 | 11.2 | 15.4 | 10.4 | 3.9 |

| College/vocational degree | 751 | 12.0 | 8.7 | 9.7 | 12.1 | 20.8 | 10.3 | 9.2 | 9.1 | 4.3 |

| Persons in household | ||||||||||

| 2–4 | 874 | 12.6 | 10.2 | 11.4 | 13.5 | 27.6 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 9.5 | 4.6 |

| 5–7 | 595 | 13.9 | 10.1 | 10.1 | 13.8 | 26.9 | 12.1 | 12.3 | 10.8 | 4.7 |

| 8–11 | 40 | 27.5 | 22.5 | 17.5 | 25.0 | 35.0 | 20.0 | 25.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| Income | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||

| < $25K | 467 | 18.8 | 14.8 | 15.4 | 16.3 | 41.1 | 16.3 | 16.9 | 13.5 | 8.8 |

| $25K – $50K | 456 | 10.3 | 9.0 | 7.9 | 13.2 | 24.8 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 7.7 | 2.4 |

| $50K – $75K | 335 | 10.1 | 6.9 | 10.7 | 12.2 | 16.7 | 9.3 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 2.7 |

| > $75K | 251 | 13.9 | 10.0 | 9.2 | 13.1 | 21.5 | 10.8 | 9.6 | 10.8 | 4.4 |

| Difficulty Managing Behavior | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Agree | 465 | 29.2 | 22.8 | 25.6 | 28.2 | 44.3 | 26.5 | 26.0 | 19.6 | 10.1 |

| Disagree | 488 | 9.4 | 6.8 | 5.9 | 9.4 | 22.5 | 7.2 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 2.7 |

| Strongly disagree | 556 | 4.0 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 5.9 | 17.8 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 4.3 | 2.2 |

Cell values are row percentages showing the proportion of respondents who reported yes to experiencing difficulty with the specified community activity.

indicates p < .0069, which is the significance threshold obtained from adjusting for the false discovery rate across all comparisons in Tables 2–4 with an initial alpha = .01.

Bold indicates |standardized residual| > 2.

Table 4.

Parent Perceptions of Participation Difficulty in Community Activities According to Environmental Factors

| Environment Factors | N | Neighborhood Outings (%)

|

Community-sponsored Activities (%)

|

Recreation & Leisure (%)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mall/store | Grocery | Restaurant | Movie | Event | Worship | Library | Vacation | Park | ||

| Total | 1,509 | 13.5 | 10.5 | 11.1 | 13.9 | 27.5 | 11.7 | 11.4 | 10.0 | 4.8 |

| Transportation | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Good to poor | 590 | 17.8 | 14.6 | 15.3 | 17.6 | 36.8 | 15.8 | 15.6 | 12.9 | 6.8 |

| Excellent | 919 | 10.8 | 7.8 | 8.4 | 11.5 | 21.5 | 9.1 | 8.7 | 8.2 | 3.5 |

| Family/Friend support | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Strongly agree | 977 | 7.9 | 6.0 | 6.6 | 9.0 | 20.0 | 7.6 | 6.7 | 6.1 | 3.0 |

| Agree | 386 | 20.2 | 14.5 | 15.5 | 21.0 | 37.8 | 17.1 | 17.1 | 14.8 | 7.0 |

| Disagree | 146 | 33.6 | 29.5 | 29.5 | 28.1 | 50.7 | 25.3 | 28.1 | 23.3 | 11.0 |

| Securing a babysitter | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Not easy | 675 | 22.7 | 18.1 | 19.3 | 23.1 | 39.0 | 20.7 | 20.7 | 17.2 | 8.3 |

| Easy | 834 | 6.1 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 6.5 | 18.2 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 1.9 |

Cell values are row percentages showing the proportion of respondents who reported yes to experiencing difficulty with the specified community activity.

indicates p < .0069, which is the significance threshold obtained from adjusting for the false discovery rate across all comparisons in Tables 2–4 with an initial alpha = .01.

Bold indicates |standardized residual| > 2.

Participation Burden and Concurrence

In response to the first study question, 60.7% of surveyed caregivers reported no difficulty participating in community activities. Of the remaining families, caregivers were 2–3 times more likely to report difficulty in 1 activity (19.8%) than in 2–3 (6.6%), 4–5 (5.7%), or 6 or more activities (7.3%). The most commonly reported area of participation difficulty was with respect to attending community events (27.5%).

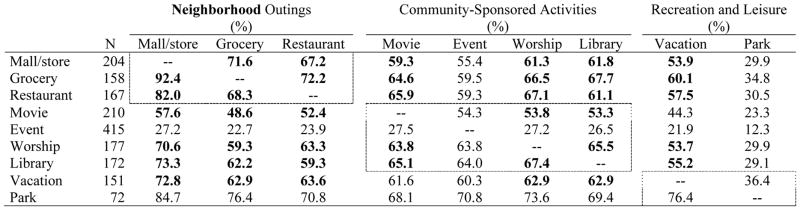

In response to the second study question, concurrences (co-reporting) of participation difficulties for 72 pairwise combinations are listed in Table 1. There were significant and strong concurrences in participation difficulty for the three types of neighborhood outings. The frequencies of co-reporting within this activity category were larger than for any pair outside the group and all three Phi coefficients were > 0.5. Significant and strong concurrences in participation difficulty were found for three of the four types of community-sponsored activities: movies, worship, and library. There were weak concurrences in participation difficulty for both activities within the recreation and leisure activity category.

Table 1.

Patterns of Co-occurrences in Parent Perceptions of Participation Difficulty in Community-Based Activities

Cell values are row percentages showing the proportion of respondents who reported yes to experiencing difficulty with the specified community activity among the n participants who also reported difficulty with the community activity identified in Column 1; i.e. the concurrence of difficulty with the column activity given difficulty with the row activity. Bold indicates Phi > .5.

In the remainder of this section, we summarize results pertaining to the third study question. Participation Difficulty According to Child-Related Factors. Table 2 depicts caregiver perceptions of participation difficulties for all 9 community-based activities relative to key socio-demographic characteristics and functional abilities of their children. Child age was statistically associated with perceived difficulty participating in two of the nine activities. Caregivers of older children were more likely to experience participation restrictions across both activities. Neither child gender nor reason for Part C service eligibility was significantly associated with perceived difficulty in any activity. Child race/ethnicity was associated with one activity and was most pronounced among Hispanics attending community-sponsored events. Six of the nine indicators of child functioning were associated with perceived difficulty across all nine community-based activities.

Participation Difficulty According to Family-Related Factors

Caregiver perceptions of difficulty with managing problematic behavior were strongly related to reported participation difficulty across all nine activities. Respondent education was associated with difficulty in attending community-sponsored events. Household size was not significantly associated with perceived difficulty participating in community-based activities. Household income was associated with difficulty in seven activities.

Participation Difficulty According to Environmental Factors

Each of three environment factors was associated with difficulty participating in all nine community-based activities.

Discussion

This is the first study employing a large data source to examine the prevalence, concurrence, and contextual factors associated with participation difficulty among preschoolers with disabilities in the community setting. We found that 39.3% of surveyed caregivers reported participation difficulty that was significantly and strongly associated with a host of child and family demographic factors, child functional abilities, and environmental factors. These results are each discussed in relationship to their implications for early intervention service delivery and survey development.

Our data show strong and significant concurrences for caregiver reporting of participation difficulty in activities within the neighborhood outings category. These results suggest that there is pattern of obtaining similar responses about participation difficulty between and across activities of this type and so collapsing these items on the YC-PEM may help to decrease respondent burden when the survey is administered for research purposes. However, this level of specificity in activity groupings may still be desirable for fostering a more focused and tailored service planning approach with clients. In contrast, our data show less concurrence among activities within the community-sponsored and recreation and leisure categories that lend further support to the current activity groupings in this section of the YC-PEM.

We found that children’s functional abilities as compared to their reason for Part C service eligibility were more strongly associated with participation difficulty across 7 to 9 activities. This finding may reflect the variability in presentation of young children who access Part C early intervention services in the United States due to developmental delay. Nearly two-thirds of families are made eligible for these services because of developmental delay rather than a diagnosed condition or because they are deemed to be at high risk for disability (Hebbeler et al., 2007), and there is state-to-state variation in the criteria used to define developmental delay (Bailey et al., 1999; Guralnick, 1998; Harbin et al., 2000). These results reinforce the ICF-CY emphasis on gathering information about children’s functional abilities that can be similar across diagnoses to better understand the contribution of personal factors and functional impairments, relative to environmental factors, on their participation. When validating the YC-PEM for the purpose of model testing, we expect to gather information about the child’s functional impairments via a demographic questionnaire that will ask about the child’s problems with mobility, speech, feeding, bladder and bowel control, social skills, and safety awareness.

Similar to findings reported by Dunst and colleagues (2002), our data also suggest that caregivers of older children are more likely to experience participation restrictions in some community-based activities. For this reason, it will also be important to obtain a diverse sample with respect to child age in the validation study to assess whether the YC-PEM can detect expected age-related differences in participation restriction among children with and without disabilities. Since 60.7% of caregivers in this study reported no community participation difficulty, we expect that a portion of our validation sample will include caregivers who report no participation difficulty. This type of participation pattern is worth further exploration as it may inform service efforts to maintain the child’s participation frequency and/or involvement over time. The current structure of the YC-PEM is designed to elicit for information on parent strategy use specific to each setting and these data may help to increase the utility of the YC-PEM for service planning. Data on parent strategy use may help practitioners understand and build upon family strengths and expertise to maintain and/or promote participation in the home and/or community settings.

Families with lower levels of annual income were more likely to express participation difficulty in 7 of 9 activities. The significance of annual income as associated with community participation restriction is consistent with what has been cited in the literature (King et al., 2002; King et al., 2006; Rosenberg et al., 2010) and may be partly explained by the cost of community activities and/or obtaining information about them via member-based resources (Khetani, Cohn, et al., 2011). This finding lends support to the current structure of the YC-PEM that includes an item about the availability and adequacy of monetary resources to support community participation. We also found no differences in the response patterns of surveyed caregivers relative to household size that may reflect families’ capacities to effectively manage competing schedules of various members within the household to afford children with opportunities for participating in their communities.

In this study, surveyed caregivers reporting difficulty with managing their child’s behavior were more likely to report participation difficulty across all activities. This finding extends prior knowledge about the extent to which child behavior problems are associated with community participation difficulty (Khetani, Orsmond, et al., 2012; McIntyre, et al., 2006). Given its importance and similar pattern of association across community activities, we will add an item to the YC-PEM community environment section that asks about the extent to which child’s behavior helps or makes it harder for the child to participate in community activities.

There is increasing evidence to suggest that child factors are not as highly predictive of participation outcomes as are family and environmental factors such as social support and peer attitudes (Hardin et al., 2009; Soref et al., 2011). In this study, we found associations between each of the environmental factors we assessed in relationship to participation difficulty across all 9 activities. These results suggest that there may be setting-specific qualities in environmental influences on young children’s participation but not activity-specific influences. This finding validates the current structure of the YC-PEM with respect to capturing the participation-environment relationship with specificity at the level of a setting (home, community) rather than at the level of the specific activity. The YC-PEM addresses social support for the child and based on these study results could be expanded to address the availability and adequacy of social support to families (extended family, neighbors, friends, babysitter).

Study strengths include a relatively large sample of caregivers whose young children have accessed Part C early intervention services in the United States, data pertaining to a comprehensive set of community activities, and prompts used during data collection to elicit caregivers’ perspectives about difficulty participating in community activities because of child rather than parental preference for the activity itself. Hence, our findings lend particular strength for informing survey revisions that will increase content coverage (e.g., expansion of environmental factors) and feasibility (e.g., paring down of activity categories) when validated online for use in early intervention service planning and large-scale research.

There were several limitations to the current study. All nine outcome variables required reverse interpretation of response patterns because parents were asked to select “yes” or “strongly agree” to denote participation difficulty which could have resulted in some reporting error. While we can ascertain that participation difficulty is not due to parent preference based on the wording of survey items in the NEILS dataset, we do not know what type of participation difficulty the child was perceived to experience (e.g., difficulty due to frequency, level of involvement, or both) that may be relevant to tailoring a service plan. Furthermore, study results are based on tests of association with data obtained at a single time point so do not imply a causal relationship between child, family, and environmental factors and outcome variables. We did not build and test hypothesized pathways to community participation due to lack of NEILS data on the full range of environmental correlates of young children’s community participation, such as the physical, cognitive and social demands of activities (Bedell, Coster, Law, et al., 2012) and peer attitudes (Salisbury et al., 1995). These data will be obtained using the YC-PEM to build and test robust models of home and community participation. Finally, future studies could examine reliability of proxy survey estimates when compared to observational methods (Lucyshyn et al., 2004; Speith et al., 2001).

Conclusion

Management of everyday life is a common task for young families whose children are learning to participate in home and community activities. Caregivers of young children with disabilities encounter barriers at home and in the community and express need for support to adapt routines and make accommodations to support participation in each setting. Practitioners who assess and intervene in the lives of young children with disabilities need to assess for areas of participation restriction, the type(s) of restriction experienced, and child, family, and environmental factors that can be modified to provide effective services addressing participation as outcome, The present study expanded upon previous studies examining young children’s participation in several ways: (a) analysis of a relatively large group of cases, all having received Part C early intervention services in the United States; (b) examination of prevalence and concurrence of participation difficulty across a broad range of activities within the community setting; and (c) examination of factors associated with difficulty in one, some, or all of these activities. In the absence of a comprehensive assessment of young children’s participation and environment in the early intervention field, study results also inform the development of a new parent-report survey for improved assessment of a broad range of child-, family-, and environmentally related influences on participation frequency, level of involvement, and desire for change in home and community participation. Continued research is needed to test and apply this survey as an assessment tool for building comprehensive knowledge about young children’s participation, results of which can inform the design of more tailored interventions.

Key Messages.

Nearly 40% of caregivers with young children 0–5 years with disabilities expressed difficulty participating in community activities because of their child.

Perceptions of community participation difficulty among surveyed caregivers are significantly and strongly associated with child-, family-, and environmental factors across multiple activities in that setting.

Indicators of the young child’s functional abilities, not their service eligibility, were associated with participation difficulty across most community activities.

Contributor Information

Mary Khetani, Colorado State University.

James E. Graham, University of Texas Medical Branch

Christina Alvord, Colorado State University.

References

- Bailey DB, Aytch LS, Odom S, Symons F, Wolery M. Early intervention as we know it. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 1999;5:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Bart O. Motor function and social participation in kindergarten children. Social Development. 2006;15:296–310. [Google Scholar]

- Bedell GM, Khetani MA, Coster WJ, Cousins M, Law M. Community, social, and civic life. In: Majnemer A, editor. Measures for Children with Developmental Disabilities: Framed by the ICF-CY. Mac Keith Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bedell GM, Coster W, Law M, Liljenquist K, Kao Y-C, Teplicky R, Anaby D, Khetani MA. Community participation, supports and barriers for children with and without disabilities. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.09.024. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2012.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discover rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bernheimer LP, Keogh BK. Weaving interventions into the fabric of everyday life: an approach to family assessment. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 1995;15:415–433. doi: 10.1177/027112149501500402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Cohn E. Social participation for children with developmental coordination disorder: Conceptual, evaluation and intervention considerations. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2003;23:61–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coster W, Law M, Bedell GM. The Participation and Environment Measure for Children and Youth (PEM-CY) [Measurement Instrument] Boston University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- DeGrace BW. The everyday occupation of families with children with autism. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2004;58(5):543–550. doi: 10.5014/ajot.58.5.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunst CJ. Participation of young children with disabilities in community learning activities. In: Guralnick MJ, editor. Early childhood inclusion: Focus on change. Baltimore: Brookes; 2001. pp. 307–333. [Google Scholar]

- Dunst CJ, Bruder MB, Trivette CM, McLean M. Natural learning opportunities for infants, toddlers, and preschoolers. Young Exceptional Children. 1998;4(3):18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Dunst CJ, Hamby D, Trivette CM, Raab M, Bruder MB. Young children’s participation in everyday family and community activity. Psychological Reports. 2002;91:875–897. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2002.91.3.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Martin CL, Hanish LD. Young children’s play qualities in same-, other-, and mixed-sex peer groups. Child Development. 2003;74:921–932. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox L, Hemmeter ML. A program-wide model for supporting social emotional development and addressing challenging behavior in early childhood settings. In: Sailor W, Dunlap G, Sugai G, Horner R, editors. Handbook of Positive Behavior Support. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 177–202. [Google Scholar]

- Guralnick MJ. Effectiveness of early intervention for vulnerable children: A developmental perspective. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 1998;102:319–345. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(1998)102<0319:eoeifv>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnick MJ. Early intervention for children with intellectual disabilities: Current knowledge and future prospects. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2005;18:313–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2005.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbin GL, McWilliam RA, Gallagher JJ. Services for young children with disabilities and their families. In: Shonkoff JP, Meisels SJ, editors. Handbook of early childhood intervention. 2. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 387–415. [Google Scholar]

- Harding J, Harding K, Jamieson P, Mullally M, Politi C, Wong-Sing E, Law M, Petrenchik TM. Children with disabilities’ perceptions of activity participation and environments: A pilot study. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2009;3(3):133–144. doi: 10.1177/000841740907600302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM. SPSS, Inc, (Version 20) Chicago: IBM; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Khetani MA, Coster WJ. Social Participation. In: Schell BAB, Gillen G, Scaffa M, editors. Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy. 12. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Khetani MA, Bedell GM, Coster WJ, Cousins M, Law M. Physical, social, and attitudinal environment. In: Majnemer A, editor. Clinical and research measures for children with developmental disabilities: Framed by the ICF-CY. Mac Keith Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Khetani MA, Cohn ES, Orsmond GI, Law MC, Coster WJ. Parent perspectives of participation in home and community activities when receiving part C early intervention services. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0271121411418004. Advance online publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khetani M, Orsmond G, Cohn E, Law M, Coster W. Correlates of community participation among families transitioning from Part C early intervention services. OTJR: Occupation, Participation, and Health 2012 [Google Scholar]

- King G, Law M, King S, Rosenbaum P, Kertoy M, Young N. A conceptual model of the factors affecting the recreation and leisure participation of children with disabilities. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2003;23:63–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G, Law M, Hanna S, King S, Hurley P, Rosenbaum P, Kertoy M, Petrenchik T. Predictors of the leisure and recreation participation of children with physical disabilities: A structural equation modeling analysis. Children’s Health Care. 2006;35(3):209–234. [Google Scholar]

- LaVesser P, Berg C. Participation patterns in preschool children with an autism spectrum disorder. Occupation, Participation and Health. 2011;31(1):33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Law M. Participation in the occupations of everyday life. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2002;56:640–649. doi: 10.5014/ajot.56.6.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucyshyn JM, Irvin LK, Blumberg ER, Laverty R, Horner RH, Sprague JR. Validating the construct of coercion in family routines: Expanding the unit of analysis in behavioral assessment in families of children with developmental disabilities. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2004;29:104–121. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.29.2.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maul CA, Singer GHS. “Just good different things”: Specific accommodations families make to positively adapt to their children with developmental disabilities. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2009;29:155–170. doi: 10.1177/0271121408328516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice. 3. New Jersey: Pearson; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff B. The Cultural Nature of Human Development. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Simeonsson RJ. Early intervention eligibility: a prevention perspective. Infant & Young Children. 1991;3(4):48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury CL, Gallucci CL, Palombaro M, Peck C. Strategies that promote social relations among elementary students with and without severe disabilities in inclusive schools. Exceptional Children. 1995;62:125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Soref B, Ratzon NZ, Rosenberg L, Leitner Y, Jarus T, Bart O. Personal and environmental pathways to participation in young children with and without mild motor difficulties. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2011;38(4):561–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speith LE, Stark LJ, Mitchell MJ, Schiller M, Cohen LL, Mulvihill M, et al. Observational assessment of family functioning at mealtime in preschool children with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;26:215–224. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.4.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-Monda CS, Way N, Hughes D, Yoshikawa H, Kalman RK, Niwa EY. Parents’ goals for children: The dynamic coexistence of individualism and collectivism in cultures and individuals. Social Development. 2007;17(1):183–209. [Google Scholar]

- Weisner TS. Ecocultural understanding of children’s developmental pathways. Human Development. 2002;45(4):275–281. [Google Scholar]