Abstract

Objective

To extend the representativeness of the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Database (TBIMS-NDB) for individuals aged 16 years and older admitted for acute, inpatient rehabilitation in the United States with a primary diagnosis of traumatic brain injury (TBI) analyses completed by Corrigan and colleagues,3 by comparing this dataset to national data for patients admitted to inpatient rehabilitation with identical inclusion criteria that included 3 additional years of data and 2 new demographic variables.

Design

Secondary analysis of existing datasets; extension of previously published analyses.

Setting

Acute inpatient rehabilitation facilities.

Participants

Patients 16 years of age and older with a primary rehabilitation diagnosis of TBI; US TBI Rehabilitation population n = 156,447; TBIMS-NDB population n = 7373.

Interventions

None.

Main Outcome Measure

demographics, functional status and hospital length of stay.

Results

The TBIMS-NDB was largely representative of patients 16 years and older admitted for rehabilitation in the U.S. with a primary diagnosis of TBI on or after October 1, 2001 and discharged as of December 31, 2010. The results of the extended analyses were similar to those reported by Corrigan and colleagues. Age accounted for the largest difference between the samples, with the TBIMS-NDB including a smaller proportion of patients aged 65 and older as compared to all those admitted for rehabilitation with a primary diagnosis of TBI in the United States. After partitioning each dataset at age 65, most distributional differences found between samples were markedly reduced; however, differences on the Pre-injury vocational status of employed and rehabilitation lengths of stay between 1 and 9 days remained robust. The subsamples of patients aged 64 and younger was found to differ only slightly on all remaining variables, while those aged 65 and older were found to have meaningful differences on insurance type and age distribution.

Conclusions

These results reconfirm that the TBIMS-NDB is largely representative of patients with TBI receiving inpatient rehabilitation in the U.S. Differences between the two datasets were found to be stable across the 3 additional years of data, and new differences were limited to those involving newly introduced variables. In order to use these data for population-based research, it is strongly recommended that statistical adjustment be conducted to account for the lower percentage of patients over age 65, inpatient rehabilitation stays less than 10 days and Pre-injury vocational status in the TBIMS NDB.

Keywords: traumatic brain injury, rehabilitation, methodology

INTRODUCTION

The Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Database (TBIMS-NDB) is a prospective, longitudinal, multicenter dataset that includes information regarding recovery and long-term outcomes of individuals with a history of moderate or severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) and who receive inpatient rehabilitation at a TBIMS center.1 Patient data are accrued in the TBIMS-NDB from 16 TBIMS centers throughout the US, each of which successfully competed for funding through the TBIMS program established by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR). In addition to the funded centers, 4 previously funded centers continue to add longitudinal data for their previously enrolled cases. Only patients diagnosed with moderate or severe TBI admitted to inpatient rehabilitation meeting specific criteria (listed in Table 1) are included as cases. 2 Information in the TBIMS-NDB is collected retrospectively from acute care and prospectively during rehabilitation hospitalization, with follow up interviews at 1, 2 and 5 years post-injury, and every 5 years thereafter.

Table 1.

TBIMS Inclusion Criteria

| 1. Meet at least one of the following criteria for moderate to severe TBI: | |

| a. Post traumatic amnesia > 24 hours | or |

| b. trauma-related intracranial neuroimaging abnormalities | or |

| c. loss of consciousness exceeding 30 minutes (unless due to sedation or intoxication) | or |

| d. Glasgow Coma Score in the emergency department of less than 13 (unless due to intubation, sedation, or intoxication) | |

| 2. be at least 16 years of age at the time of injury | and |

| 3. arrive at the participating TBIMS hospital’s emergency department within 72 hours of injury | and |

| 4. receive comprehensive rehabilitation in the TBIMS brain injury program | and |

| 5. give written informed consent. |

Since the inception of the TBIMS-NDB in 1988, there have been concerns about the generalizability of these data. In 2011, a comprehensive analysis of the representativeness of the TBIMS-NDB for all cases accrued between October 1, 2001 and December 31, 2007 was completed by Corrigan and colleagues.3 These analyses compared demographic, personal, injury, and functional related characteristics of cases within the TBIMS-NDB with a national sample of cases receiving inpatient rehabilitation for a primary diagnosis of TBI in the US across identical time periods. The national sample was comprised of all cases in the two central data repositories that serve as intermediaries for the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which includes reporting on patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation,4 including those with Medicare and non-Medicare payers. The two central repositories are the Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation (UDSMR)5 and the American Medical Rehabilitation Providers Association database, eRehabData.6 At the time of these analyses, it was approximated that the national sample included no less than 92% of all civilian rehabilitation facilities.3 Because these facilities include the largest rehabilitation facilities in the country, the sample is thought to include close to 100% of all cases age 16 and older with a primary diagnosis of TBI in the US.

Results of the 2011 Corrigan et al analyses found the TBIMS-NDB was largely representative of the national population of patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation with a primary diagnosis of TBI. The principal contrast between the national data and the TBIMS-NDB was found to be age-related, with the national data having more cases aged 65 and older, more cases with Medicare as a payment source, and less cases that reported never being married. After discovering this difference, separate analyses were repeated for cases less than age 65, and those aged 65 and older. The subsequent results revealed few minor dissimilarities between the datasets when comparing cases aged 64 and younger; with one notable difference being length of stay, which was more likely to be shorter (1 to 9 days) in the national sample. Cases aged 65 and older demonstrated more notable differences, with a higher percentage of cases aged 65 to 69 in the TBIMS and 80 to 89 in the national sample, higher rates of Medicare as a payment source in the national sample, and shorter lengths of stay (1 to 9 days) in the national sample.3

The implications of the analyses completed by Corrigan and colleagues are far reaching. These findings provide evidence that analyses using the TBIMS-NDB can largely be considered generalizable to the national population of patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation for TBI in the US, particularly for cases accrued between the last three months of 2001 to 2007 who were aged 16 to 64 at the time of admission. In addition, these analyses have established standards by which the data within the TBIMS-NDB can be weighted to match the admission characteristics of the true national population receiving inpatient rehabilitation for TBI. Implementing these weights allows researchers to utilize the TBIMS-NDB to calculate prevalence estimates of long term sequelae for this population.

PURPOSE

Since the completion of the initial representativeness analyses,3 three additional years of data (2008 to 2010) have become available from both central data repositories. Two variables not included in the initial analyses are also available in these data, including pre-injury vocational status and pre-injury living status. Using these data, we will extend the analyses completed by Corrigan and colleagues to include the additional years of data and the two newly available variables. The results of these analyses will provide a decade-long comparison of the two datasets, and decade-based national estimates by which the TBIMS-NDB can be weighted for future research.

METHODS

Data Sources

The inclusion criteria were similar to the study completed by Corrigan and colleagues;3 however, the end date for inclusion was adjusted to encompass the extended sample. The date range used included those cases admitted to inpatient rehabilitation on or after October 1, 2001 and discharged as of December 31, 2010.

U.S. TBI Rehabilitation Population

A national dataset of patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation aged 16 years or older with a primary diagnosis of TBI who were admitted or discharged in the given date range was developed by combining records from UDSMR and eRehabData datasets. Case inclusion was identical to that used in the previous analysis, limiting inclusion to those with an admission class code of Initial Rehabilitation (code 1), an Impairment Group Code of 2.21 or 2.22 (Open Traumatic Brain Injury, Closed Traumatic Brain Injury)7 and either a diagnosis or comorbidity code that met the ICD-9-CM case definition of TBI established by the CDC (800.0–801.9, 803.0–804.9, 850.0–854.1, 959.01).8 The final sample included 156,447 cases, which will be labeled the “U.S. TBI Rehabilitation” population henceforward.

TBIMS-NDB

The TBIMS-NDB sample was limited to cases with a known age of 16 or older at the time of inpatient rehabilitation admission and an inpatient rehabilitation admission/discharge during the same time period used for selecting the U.S. TBI Rehabilitation population. A total of 7,373 cases were selected from the TBIMS-NDB, which consisted of 20 centers (16 fully funded centers and 4 centers only funded to continue follow-up on cases already enrolled in the TBIMS-NDB) during the designated time period.

Variables of Interest

Variables selected for comparison included all of those in the initial Corrigan et al publication3, as well as two additional demographic variables.

Demographic Factors

Demographic variables of interest were age at rehabilitation admission, gender, marital status, race/ethnicity, pre-injury living status and pre-injury vocational status. Age was grouped by 10-year intervals (see Table 3). Marital status was categorized by Single (Never married), Married, and Previously married. Race/ethnicity was categorized as African-American (non-Hispanic), Caucasian (non-Hispanic), Hispanic and “Other,” which included non-Hispanic individuals with a race code indicating Asian, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Native American/Aleut and unspecified. Pre-injury living status was grouped by categories of living Alone, With others, or living in some other arrangement (e.g. living in a group home or residing in a medical facility). Pre-injury vocational status was categorized as Working, Sheltered employment, Student, Homemaker, Not working, all types of Retirement and Other.

Table 3.

Comparison of the U.S. Population of Adults Receiving Inpatient Rehabilitation for a Primary Diagnosis of TBI to the TBI Model Systems National Database (October 1, 2001 through December 31, 2010)

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. TBI Rehab population (n=156,447) | U.S. TBI Rehab excluding TBIMS (n=149,074) | TBIMS (n=7,373) | U.S. TBI Rehab Minus TBIMS Difference (US Includes TBIMS) | U.S. minus TBIMS Difference (U.S. excludes TBIMS) | |

| Age at rehabilitation admission (%) | |||||

| 16–19 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 11.8 | −5.8* | −6.1* |

| 20–29 | 12.7 | 12.1 | 25.6 | −12.9† | −13.5† |

| 30–39 | 8.1 | 7.8 | 14.3 | −6.2* | −6.5* |

| 40–49 | 10.6 | 10.3 | 16.6 | −6.0* | −6.3* |

| 50–59 | 10.8 | 10.7 | 12.7 | −1.9 | −2.0 |

| 60–69 | 11.2 | 11.3 | 8.3 | 2.9 | 3.0 |

| 70–79 | 17.6 | 18.0 | 6.1 | 11.5† | 11.9† |

| 80–89 | 19.5 | 20.2 | 4.1 | 15.4† | 16.1† |

| 90–99 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 3.1 |

| 100 & Older | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Missing | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

|

| |||||

| Gender (%) | |||||

| Male | 64.3 | 63.8 | 72.9 | 8.6* | −9.1* |

| Female | 35.7 | 36.2 | 27.1 | −8.7* | 9.1* |

| Missing | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

|

| |||||

| Marital status (%) | |||||

| Never married | 30.7 | 30.0 | 45.8 | −15.1† | −15.8† |

| Married | 41.0 | 41.4 | 33.0 | 8.0* | 8.4* |

| Previously married | 26.2 | 26.4 | 21.1 | 5.1* | 5.3* |

| Missing | 2.1 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

|

| |||||

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | |||||

| Caucasian | 77.4 | 77.8 | 69.8 | 7.7* | 8.0* |

| African American | 8.9 | 8.5 | 17.3 | −8.4* | −8.8* |

| Hispanic | 7.1 | 7.0 | 9.1 | −2.0 | −2.1 |

| Other | 5.2 | 5.2 | 3.8 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Missing | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

|

| |||||

| Pre-injury living status (%) | |||||

| Alone | 23.8 | 24.1 | 17.8 | 6.1* | 6.3* |

| With others | 71.8 | 71.4 | 80.3 | −8.5* | −8.9* |

| Other | 2.7 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Missing | 1.6 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

|

| |||||

| Pre-injury vocational status (%) | |||||

| Employed | 29.7 | 28.2 | 60.6 | −30.9† | −32.4† |

| Sheltered | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | −0.1 | −0.1 |

| Student | 5.4 | 5.4 | 6.6 | −1.1 | −1.2 |

| Homemaker | 1.3 | 1.3 | 2.4 | −1.1 | −1.1 |

| Not working | 12.2 | 12.1 | 12.6 | −0.4 | −0.5 |

| Retired – any reason | 47.1 | 48.6 | 16.9 | 30.2† | 31.7† |

| Missing | 4.2 | 4.4 | 0.7 | 3.5 | 3.7 |

|

| |||||

| Primary payment source for rehabilitation (%) | |||||

| Private insurance | 33.6 | 33.0 | 47.0 | −13.4† | −14.0† |

| Medicare | 46.3 | 47.9 | 13.7 | 32.6† | 34.2† |

| Medicaid | 8.6 | 8.0 | 21.1 | −12.5† | −13.1† |

| Workers Compensation | 3.3 | 3.2 | 5.0 | −1.7 | −1.8 |

| Self- or No Pay | 5.5 | 5.3 | 9.4 | −3.9 | −4.1 |

| Other | 2.7 | 2.8 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| Missing | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.1 | −3.1 | −3.1 |

|

| |||||

| Days to rehabilitation admission | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 18.3 (24.6) | 18.2 (25.0) | 20.6 (16.4) | −2.3 | −2.4 |

|

| |||||

| FIM Total at admission | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 54.8 (21.9) | 54.9 (21.8) | 50.5 (23.6) | 4.3 | 4.4 |

|

| |||||

| FIM Motor at admission (%) | |||||

| 13 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 13.9 | −6.5* | −6.8* |

| 14 through 23 | 16.9 | 16.8 | 19.8 | −2.9 | −3.0 |

| 24 through 33 | 16.9 | 17.0 | 15.6 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| 34 through 43 | 19.8 | 20.0 | 15.7 | 4.1 | 4.3 |

| 44 through 53 | 21.1 | 21.4 | 15.6 | 5.5* | 5.8* |

| 54 through 63 | 12.7 | 12.8 | 10.3 | 2.4 | 2.5 |

| 64 through 73 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 4.9 | −1.0 | −1.1 |

| 74 through 83 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.5 | −0.5 | −0.4 |

| 84 through 91 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | −0.1 | −0.1 |

| Missing | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

|

| |||||

| FIM Cognitive at admission (%) | |||||

| 5 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 14.4 | −5.0* | −5.2* |

| 6 through 15 | 34.6 | 34.5 | 36.9 | −2.3 | −2.4 |

| 16 through 25 | 38.8 | 38.9 | 36.4 | 2.4 | −2.5 |

| 26 through 35 | 17.2 | 17.5 | 11.7 | 5.5* | 5.8* |

| Missing | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | −0.6 | −0.6 |

|

| |||||

| Case mix group (%) | |||||

| 201 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 202 | 6.7 | 5.8 | 4.1 | 2.6 | 1.7 |

| 203 | 16.6 | 16.6 | 15.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| 204 | 11.8 | 12.0 | 8.8 | 3.1 | 3.2 |

| 205 | 30.3 | 30.4 | 29.3 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| 206 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 8.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| 207 | 19.2 | 19.0 | 24.0 | −4.8 | −5.0* |

| Missing | 1.3 | 1.1 | 5.1 | −3.8 | −4.0 |

|

| |||||

| Rehab-LOS in days (minus interruptions) (%) | |||||

| 1 through 9 | 29.1 | 29.7 | 16.7 | 12.4† | 13.0† |

| 10 through 19 | 40.5 | 40.9 | 33.6 | 6.9 | 7.3 |

| 20 through 29 | 18.5 | 18.4 | 22.3 | −3.8 | −3.9 |

| 30 through 39 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 10.2 | −4.3 | −4.4 |

| 40 through 49 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 5.0 | −2.5 | −2.6 |

| 50 through 59 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 3.2 | −2.0 | −2.1 |

| 60 through 69 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 2.0 | −1.3 | −1.3 |

| 70 through 79 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.2 | −0.7 | −0.8 |

| 80 through 89 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.8 | −0.5 | −0.5 |

| 90 through 99 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | −0.4 | −0.4 |

| 100 + | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.4 | −0.9 | −1.0 |

| Missing | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.2 | −3.2 | −3.2 |

| Mean (SD) | 17.5 (15.2) | 17.1 (14.9) | 24.7(22.8) | −7.2** | −7.6†† |

indicates differences within categorical variables with an absolute value ≥ 5% but < 10%

indicates differences within categorical variables with an absolute value ≥ 10%

indicates differences ≥ 25% but < 50% of 1 SD for the U.S. population

indicates differences ≥ 50% of 1 SD for the U.S. population

Rehab = Rehabilitation, TBIMS = Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Database, FIM = Functional Independence Measure, LOS = length of stay

Primary Insurance

Primary payment source for inpatient rehabilitation was grouped by Medicare, Medicaid, Workers Compensation, Self-Pay or No Pay, Private insurance and Other.

Functional Status

Functional status variables included the component scores of the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) taken within 72 hours of admission to rehabilitation,7 including the FIM Motor, FIM Cognitive and FIM Total scores. FIM Motor and Cognitive scores were compared categorically using minimum scores, and subsequent 10-point ranges. FIM Total scores were evaluated as continuous variables.

Time to Rehabilitation Admission and Rehabilitation Length of Stay

Time to rehabilitation admission was evaluated as a continuous variable, reflecting the number of days from injury to rehabilitation admission. Rehabilitation length of stay (Rehab-LOS) was calculated as days from inpatient rehabilitation admission to discharge, and compared both in 10 day categories, and as a continuous variable. Cases with interrupted rehabilitation stays of three or less days had Rehab-LOS calculated as days from admission to discharge, excluding the days of interruption. Cases with an interruption longer than three days had Rehab-LOS calculated as the days from admission to the first day of this interruption. For the latter cases, subsequent admissions were not included in the analyses.

Case-Mix Group (CMG)

For cases admitted prior to October 1, 2005, CMGs were determined using simple additive FIM motor and cognitive scores, while those admitted on or after October 1, 2005 were computed using the weighted motor score described in the August 15, 2005 Federal Register.9

ANALYSES

Each of the variables of interest was compared across the TBIMS-NDB and the U.S. TBI Rehabilitation population. Statistical tests were not used as the large sample sizes would cause any differences to be statistically significant. The classification schema used to describe database differences established in the previous analyses3 was implemented here, and is listed in table 2.

Table 2.

Classification of Distributional Differences Between U.S. TBI Rehabilitation Population and TBI Models Systems National Database

| Distributional Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Immaterial | Minor | Important | ||

|

|

||||

| Data Type | Categorical | <|5.0%| | ≥|5.0%| to < |10.0%| | ≥|10.0%| |

| Continuous | <|25.0%| SD | ≥|25.0%| SD to <|50%| SD | ≥|50.0%| | |

|

|

||||

Initial analyses compared the U.S. TBI Rehabilitation population with the TBIMS-NDB cohort as both the Total population and the Total without TBIMS-NDB cases. TBIMS centers submit cases to either the UDSMR or eRehabData databases; thus, in order to evaluate the samples as completely independent cohorts, TBIMS cases were removed from the comparison cohort by subtracting the aggregate frequencies. Initial database comparisons were completed using the U.S TBI rehabilitation population with and without the TBIMS cases.

RESULTS

The results of the TBIMS-NDB and U.S. TBI Rehabilitation comparisons across each of the variables of interest are listed in Table 3. Differences found were similar to those previously reported,3 with minor or important distinctions in at least one level for 9 of the 11 categorical variables, as well as 1 of the 3 continuous variables. Important differences included Age (the TBIMS-NDB cohort tended to be younger), Marital status (the TBIMS-NDB cohort was more likely to be Never married), Pre-Injury living status (the TBIMS-NDB cohort was more likely to live With other(s)), Pre-injury vocational status (the TBIMS-NDB cohort was more likely to be Employed and less likely to be Retired), Primary payment source for rehabilitation (TBIMS patients were more likely to have Private insurance or Medicaid and less likely to have Medicare) and Rehab-LOS (the TBIMS-NDB patients were less likely to have a 1 – 9 day stay). The mean difference for Rehab-LOS also showed a minor difference for the U.S. TBI Rehabilitation population with TBIMS-NDB cases included, but important difference for the U.S. TBI Rehabilitation population without those cases. Categories demonstrating minor differences included all those noted by Corrigan and colleages,3 with the addition of Pre-injury living status ‘Alone’ (TBIMS-NDB less likely to live alone).

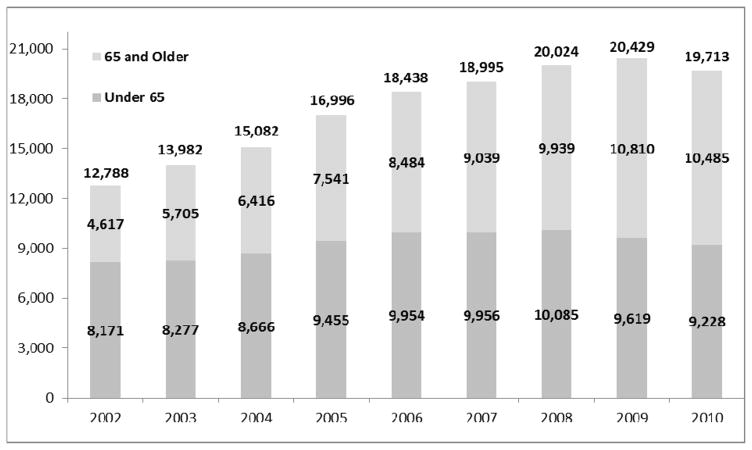

As was noted in the analysis from the seven year comparison,3 the age of the cohorts demonstrated the largest dissimilarity across databases, with additional demographic and personal characteristics showing important differences highly associated with Age (Gender, Marital status, Pre-injury vocational status, Pre-injury living status, Primary payment source). To address this central issue, the datasets were split at age 65, creating two sub-datasets, one containing cases 64-and-younger, and the other containing cases 65-and-older. Comparisons between the TBIMS-NDB and the US TBI Rehabilitation population were then recomputed for each age-specific sub-dataset and are presented in Table 4. For descriptive purposes, yearly incidence rates of patients receiving rehabilitation for both age cohorts were calculated across each available year of data. Annual changes in the distribution of those under 65 and those 65 and older are shown in Figure 1.

Table 4.

Comparison of the U.S. Population of Adults Receiving Inpatient Rehabilitation for a Primary Diagnosis of TBI to the TBI Model Systems National Database Stratified by Age. (U.S. population includes the TBIMS cases): October 1, 2001 to December 31, 2010

| < 65 years old

|

65 + years old

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. TBI Rehab population | TBIMS | U.S. minus TBIMS Difference | U.S. TBI Rehab population | TBIMS | U.S. minus TBIMS Difference | |

| Age at rehabilitation admission (%) | ||||||

| 16–19 | 11.2 | 13.8 | −2.6 | -- | -- | -- |

| 20–29 | 23.8 | 29.9 | −6.1* | -- | -- | -- |

| 30–39 | 15.3 | 16.7 | −1.4 | -- | -- | -- |

| 40–49 | 19.9 | 19.3 | 0.6 | -- | -- | -- |

| 50–59 | 20.3 | 14.8 | 5.5* | -- | -- | -- |

| 60–64 | 9.5 | 5.4 | 4.1 | -- | -- | -- |

| 65–69 | -- | -- | -- | 13.1 | 24.9 | −11.8† |

| 70–79 | -- | -- | -- | 37.5 | 42.6 | −5.1* |

| 80–89 | -- | -- | -- | 41.8 | 28.7 | 13.1† |

| 90–99 | -- | -- | -- | 7.5 | 3.8 | 3.7 |

| 100 & Older | -- | -- | -- | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Missing | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Gender (%) | ||||||

| Male | 74.3 | 75.6 | −1.3 | 52.7 | 57.2 | −4.5 |

| Female | 25.6 | 24.4 | 1.2 | 47.3 | 42.8 | 4.5 |

| Missing | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Marital status (%) | ||||||

| Never married | 50.3 | 52.2 | −1.9 | 8.3 | 7.3 | 1.0 |

| Married | 33.5 | 29.9 | 3.6 | 49.7 | 51.8 | −2.1 |

| Previously married | 13.7 | 17.8 | −4.1 | 40.5 | 40.8 | −0.3 |

| Missing | 2.5 | 0.1 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 1.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | 71.5 | 68.1 | 3.4 | 84.2 | 79.9 | 4.3 |

| Caucasian | 12.1 | 18.5 | −6.4* | 5.2 | 9.9 | −4.7 |

| African American | 9.3 | 9.6 | −0.3 | 4.5 | 5.9 | −1.4 |

| Hispanic | 5.4 | 3.8 | 1.6 | 4.8 | 4.3 | 0.5 |

| Other | 1.5 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| Missing | 71.5 | 68.1 | 3.4 | 84.2 | 79.9 | 4.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Pre-injury living status (%) | ||||||

| Alone | 18.1 | 16.1 | 2.0 | 30.4 | 27.7 | 2.7 |

| With others | 78.2 | 82.3 | −4.1 | 64.5 | 68.3 | −3.8 |

| Other | 2.4 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 4.0 | −0.9 |

| Missing | 1.3 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 1.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Pre-injury vocational status (%) | ||||||

| Employed | 51.3 | 68.1 | −17.2† | 5.0 | 16.5 | −11.5† |

| Sheltered | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | −0.1 |

| Student | 10.2 | 7.6 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 0.2 | −0.2 |

| Homemaker | 1.2 | 2.0 | −0.8 | 1.5 | 4.5 | −3.0 |

| Not working | 21.1 | 14.3 | 6.8* | 1.9 | 3.5 | −1.6 |

| Retired – any reason | 12.3 | 7.2 | 5.1* | 86.8 | 75.0 | 11.8† |

| Missing | 3.8 | 0.5 | 3.4 | 4.7 | 0.2 | 4.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Primary Payment Source for rehabilitation (%) | ||||||

| Private insurance | 55.3 | 51.6 | 3.7 | 8.8 | 19.8 | −11.0† |

| Medicare | 8.8 | 4.0 | 4.8 | 89.2 | 71.5 | 17.7† |

| Medicaid | 15.6 | 23.9 | −8.3* | 0.6 | 4.5 | −3.9 |

| Workers Compensation | 5.5 | 5.5 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 1.5 | −0.8 |

| Self- or No Pay | 10.2 | 10.8 | −0.6 | 0.2 | 1.2 | −1.0 |

| Other | 4.6 | 0.9 | 3.7 | 0.5 | 1.4 | −0.9 |

| Missing | 0.0 | 3.4 | −3.4 | 0.0 | 1.4 | −1.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Days to rehabilitation admission | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 23.3 (30.5) | 21.8 (16.7) | 1.5 | 12.6 (17.9) | 13.7 (12.7) | −1.1 |

|

| ||||||

| FIM Total at admission | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 54.6 (23.9) | 50.6 (24.1) | 4.0 | 55.4 (19.3) | 49.3 (19.8) | 6.1** |

|

| ||||||

| FIM Motor at admission | ||||||

| 13 | 9.9 | 14.8 | −4.9 | 4.5 | 8.7 | −4.2 |

| 14 through 23 | 17.0 | 19.5 | −2.5 | 16.9 | 22.0 | −5.1* |

| 24 through 33 | 13.3 | 14.4 | −1.1 | 21.0 | 22.9 | −1.9 |

| 34 through 43 | 15.9 | 14.9 | 1.0 | 24.3 | 20.3 | 4.0 |

| 44 through 53 | 19.9 | 15.7 | 4.2 | 22.4 | 14.7 | 7.7* |

| 54 through 63 | 15.6 | 10.8 | 4.8 | 9.3 | 7.0 | 2.3 |

| 64 through 73 | 6.1 | 5.4 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 1.9 | −0.6 |

| 74 through 83 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 84 through 91 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Missing | 0.0 | 2.3 | −2.3 | 0.0 | 2.5 | −2.5 |

|

| ||||||

| FIM Cognitive at admission | ||||||

| 5 | 12.5 | 15.3 | −2.8 | 5.9 | 9.0 | −3.1 |

| 6 through 15 | 38.4 | 36.9 | 1.5 | 30.3 | 36.9 | −6.6* |

| 16 through 25 | 35.1 | 35.6 | −0.5 | 42.9 | 40.8 | 2.1 |

| 26 through 35 | 14.0 | 11.5 | 2.5 | 20.9 | 12.9 | 8.0* |

| Missing | 0.0 | 0.6 | −0.6 | 0.0 | 0.5 | −0.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Case mix group | ||||||

| 201 | 6.6 | 4.9 | 1.7 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 0.8 |

| 202 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 1.4 | 8.0 | 4.2 | 3.8 |

| 203 | 22.3 | 16.8 | 5.5* | 10.0 | 9.4 | 0.6 |

| 204 | 10.8 | 8.9 | 1.9 | 13.0 | 7.7 | 5.3* |

| 205 | 28.1 | 28.9 | −0.8 | 32.7 | 32.0 | 0.7 |

| 206 | 6.7 | 7.4 | −0.7 | 11.8 | 14.4 | −2.6 |

| 207 | 18.3 | 23.7 | −5.4* | 20.4 | 26.0 | −5.6* |

| Missing | 0.0 | 5.2 | −5.2 | 0.9 | 4.0 | −3.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Rehab-LOS in days (minus interruptions) | ||||||

| 1 through 9 | 30.2 | 17.0 | 13.2† | 27.8 | 14.7 | 13.1† |

| 10 through 19 | 34.2 | 32.9 | 1.3 | 47.7 | 38.0 | 9.7* |

| 20 through 29 | 18.3 | 21.7 | −3.4 | 18.8 | 26.0 | −7.2* |

| 30 through 39 | 7.6 | 10.3 | −2.7 | 4.1 | 9.7 | −5.6* |

| 40 through 49 | 3.9 | 5.2 | −1.3 | 1.0 | 3.8 | −2.8 |

| 50 through 59 | 2.0 | 3.3 | −1.3 | 0.3 | 2.3 | −2.0 |

| 60 through 69 | 1.2 | 2.3 | −1.1 | 0.1 | 0.7 | −0.6 |

| 70 through 79 | 0.8 | 1.2 | −0.4 | 0.1 | 0.8 | −0.7 |

| 80 through 89 | 0.5 | 0.9 | −0.4 | 0.0 | 0.3 | −0.3 |

| 90 through 99 | 0.4 | 1.5 | −1.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | −0.2 |

| 100 + | 0.8 | 1.5 | −0.7 | 0.0 | 0.3 | −0.3 |

| Missing | 0.0 | 2.8 | −2.8 | 0.0 | 3.4 | −3.4 |

| Mean (SD) | 19.8 (18.9) | 25.2 (23.8) | −5.4** | 15.1 (9.1) | 21.2 (14.3) | −6.1†† |

indicates differences within categorical variables with an absolute value ≥ 5% but < 10%

indicates differences within categorical variables with an absolute value ≥ 10%

indicates differences ≥ 25% but < 50% of 1 SD for the U.S. population

indicates differences ≥ 50% of 1 SD for the U.S. population

Rehab = Rehabilitation, TBIMS = Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Database, FIM = Functional Independence Measure, C = FIM Cognitive, M = FIM Motor, LOS = length of stay

Figure 1.

Yearly U.S. Inpatient Rehabilitation Admissions of Patients Aged 16 and Older With A Primary Diagnosis of TBI (2002 – 2010)

Sample partitioned at age 65

Cross-database comparisons for cases 64-and-younger demonstrated 2 variables with 1 category of ‘important’ difference, Rehab-LOS and Pre-injury vocational status, with TBIMS cases less likely to have stays of 1 to 9 days and more likely to be Employed. Minor differences were the age category 20 to 29 (TBIMS had more), the Primary payment source for rehabilitation category of Medicaid (TBIMS had more), the Pre-injury vocational status categories of Not working and Retired (TBIMS had less of both), and CMGs 203 and 207 (TBIMS had less 203, more 207).

Important differences noted in the comparison of 65-and-older samples included the Age categories of 65 to 69 and 80 to 89 (TBIMS had more of the former, less of the latter), the Primary payment source for rehabilitation categories of Private insurance and Medicare (TBIMS had more private insurance and less Medicare), the Pre-injury vocational status categories of Employed and Retired (TBIMS had more Employed less Retired) and the Rehab-LOS category of 1 to 9 days (TBIMS had fewer short lengths of stay). Minor differences included the Age category of 70 to 79 (TBIMS had more), FIM Motor scores at admission of 14 to 23 and 44 to 53 (TBIMS scores tended to be lower), FIM Cognitive scores at admission of 6 to 15 and 26 to 35 (TBIMS scores tended to be lower), CMG 204 and 207 (TBIMS cases tended to have higher CMG scores), and Rehab-LOS categories of 10 to 19, 20 to 29, and 30 to 39 (with TBIMS cases tending to have more stays of these lengths).

DISCUSSION

The current study extends the analyses completed by Corrigan and colleagues3 comparing the TBIMS-NDB and the U.S. TBI Rehabilitation population across 3 additional years of data and 2 new variables. The results of this extension study demonstrates that cases aged 16 years and older with a primary diagnosis of TBI that comprise TBIMS-NDB are similar to the cohort of cases aged 16 years and older admitted for initial rehabilitation with a primary diagnosis of TBI from the U.S. TBI Rehabilitation population. As with the original analyses, the primary difference between these two cohorts was age, with the TBIMS-NDB sample having a lower proportion of cases aged 65 and older than the U.S. TBI Rehabilitation population. After partitioning the datasets at age 65, many of the differences between the databases were diminished, particularly for the 64 years of age and younger cohort.

Differences that were found to be ‘important’ between the 64-and-younger cohort included Pre-injury vocational status and Rehab-LOS. The TBIMS-NDB cohort was found to have a smaller percentage of cases with rehabilitation lengths of stay between 1 to 9 days and was also more likely to have a Pre-injury vocational status of Employed, as compared to the U.S. TBI Rehabilitation population. Beyond these categories, few minor differences were noted, with the majority of comparisons between the cohorts showing ‘immaterial’ differences. These results suggest that this portion of the TBIMS-NDB is well suited for estimating national outcomes, particularly the demographic, socioeconomic, psychological, psychosocial, participatory and disability-related outcomes collected longitudinally within this dataset.

Comparisons between the cohorts of cases aged 65 and older demonstrated more pronounced dissimilarities, with seven categories having ‘important’ differences. Many of these dissimilarities appear linked to Age. The TBIMS-NDB sample has a higher percentage of cases aged 65 to 69 and less aged 80 to 89. As such, it is not surprising that TBIMS-NDB cases were more likely to have a Pre-injury vocational status of Employed and less likely to be Retired, and more likely to use Private insurance as a Primary payment source for rehabilitation and less likely to use Medicare. Unrelated to age-linked differences, Rehab-LOS was also found to have an ‘important’ difference, with cases in the TBIMS-NDB less likely to have stays of 1 to 9 days.

These results do not differ substantially from the previously published analyses.3 The majority of differences between the datasets appear to stem from the age distributions across datasets. Once these are resolved, the datasets become much more aligned, with the only remaining important difference across the two age-subdivided datasets being rehabilitation lengths of stay between 1 and 9 days. Furthermore, it appears that the differences between the TBIMS-NDB and the U.S. TBI Rehabilitation populations have remained relatively stable over the additional 3 years included here. Differences not found in the initial analyses were limited to those new variables included in these analyses, with most previously determined comparisons demonstrating only slight changes.

Annual incidence rates for the U.S. TBI Rehabilitation population provide insight into the yearly impact of new TBI inpatient rehabilitation admissions in the U.S. These data demonstrated a steady increase in inpatient rehabilitation incidence for initial rehabilitation of patients aged 16 and older with a primary diagnosis of TBI between 2002 and 2006, followed by a gradual leveling of this population near 20,000 cases per year. Despite the stabilization of the total population of adults admitted to rehab for TBI, the age distribution of this population demonstrates a change across almost all years of available data. With the exception of 2010, the percentage of adults aged 65 and older within this population demonstrated a steady increase from 36% to 53%. Awareness of the changing age distribution of adults receiving rehabilitation for TBI may be useful for rehabilitation administrators and policymakers as they plan future health resources distribution.

Limitations

These analyses are subject to a few limitations. The schema applied for assessing differences between the databases may be too lenient, and more strict criteria for the classification of ‘immaterial’, ‘minor’ and ‘important’ may be justified. These analyses are also limited in the comparability of the two datasets. Whereas the TBIMS includes only cases that are moderate or severe, the U.S. TBI Rehabilitation population may include cases that are mild in nature, and such cases may influence the categories compared across the data (e.g. Rehab-LOS 1–9 days). Furthermore, the most severe cases of TBI may well be included in the TBIMS-NDB sample, as the centers providing cases to this dataset have been established as ‘model centers’ for TBI rehabilitation. The increased likelihood of these severe cases within the TBIMS-NDB may inherently imbalance the categories compared across databases (e.g. CMG 207). Variables that could be used to illuminate these differences (Glasgow Coma Scale, length of post traumatic amnesia, length of unconsciousness) are unavailable for the U.S. TBI Rehabilitation sample.

As noted in the previous analyses,3 these comparisons apply to only those data for cases accrued between October 1, 2001 and December 31, 2010. Thus, publications that utilize the entire TBIMS-NDB for analyses should not immediately be deemed representative of all patients with TBI receiving inpatient rehabilitation in the US. In order to assume representativeness for analyses that stem from this dataset, the data should be limited to those years analyzed here, and should likely be weighted to adjust for those differences found to be ‘important’.

SUMMARY

The results of this study demonstrate that the TBIMS-NDB is representative of the U.S. TBI Rehabilitation population using this near decade long comparison, particularly for cases younger than 65. Analyses that utilize the TBIMS-NDB that wish to generalize their findings to the national population of patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation for a primary diagnosis of TBI would be well served to adjust for the important differences demonstrated in these analyses, including ages greater than 65, Pre-injury vocational status and Rehab-LOS.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an intra-agency agreement between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR) with supplemental funding to the NIDRR-funded Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Data and Statistical Center (grant no. H133A110006). It was also supported by a Traumatic Brain Injury Model System Centers grant from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research to Ohio State University (grant no. H133A070029), and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research within the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant no. R24 HD065702). This article does not reflect the official policy or opinions of the CDC or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and does not constitute an endorsement of the individuals or their programs—by CDC, HHS, or other components of the federal government—and none should be inferred. No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit upon the authors or upon any organization with which the authors are associated. The TBI Model Systems National Database is supported by NIDRR and created and maintained by the TBI Model Systems Centers Program. However, these contents do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the TBI Model Systems Centers, NIDRR or the U.S. Department of Education.”

References

- 1.Dijkers MP, Harrison-Felix C, Marwitz JH. The traumatic brain injury model systems: history and contributions to clinical service and research. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2010;25(2):81–91. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181cd3528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.TBI Model Systems National Data and Statistical Center. Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Database Syllabus. www.tbindsc.org/Syllabus.aspx. Updated 2012.

- 3.Corrigan JD, Cuthbert JP, Whiteneck GG, Dijkers MP, Coronado V, et al. Representativeness of the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Database. J Head Trauma Rehabil. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3182238cdd. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stineman MG. Prospective payment, prospective challenge. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(12):1802–1805. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.36067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UDS. [Accessed 04/29/2011];Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation. http://www.udsmr.org/Default.aspx. Updated 2010.

- 6.eRehabData. [Accessed 04/29/2011]; https://web2.erehabdata.com/erehabdata/index.jsp.

- 7.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility-Patient Assessment Instrument (IRF-PAI) Training Manual. www.cms.hhs.gov/InpatientRehabFacPPS/downloads/irfpaimanual040104.pdf.

- 8.Marr A, Coronado V. Central Nervous System Injury Surveillance Data Submission Standards –2002. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2004. [Accessed April 2, 2012]. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medicare Program; Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Prospective Payment System for FY 2006; Final Rule. 2005;42 CFR:Part 412.