Abstract

Objective:

The aim of the study was to assess the dentition status and the treatment needs of the HIV-positive patients on ART for more than a year in Raichur, Karnataka.

Materials and Methods:

Convenience sampling was followed. The sample size was 170. The dentition status and treatment needs of the patients were recorded as per the WHO guidelines.

Results:

The overall prevalence of dental caries was 79.4%. Males had higher percentage of dental caries than the females, and this was found to be statistically significant. The prevalence of dental caries was higher among the participants who used finger to clean their teeth compared to the toothbrush, neem stick, and charcoal users, and this was found to be statistically significant.

Conclusion:

Higher prevalence of dental caries was observed among the study population. Most of them required some type of treatment. Patients with a low CD4 count required higher treatments than the others.

Keywords: Antiretroviral treatment, dentition status, HIV, India, treatment needs

INTRODUCTION

The continuous increase in number of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) represents a serious health and economic burden that the world is facing.[1] The United Nations AIDS estimates that there are 33.4 millions who are suffering from HIV in the world all over. This is 20% more than what it was for the year 2001. In the year 2011–2012, 1.67 lakhs cases of HIV were identified.[2] HIV prevention must be a multidisciplinary approach involving physicians, dentists, pharmacists, nurses, health educators, therapists, and other health-care providers.[3] According to the National AIDS Control Organization, there are six high prevalent states-Karnataka, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Manipur and Nagaland and 76% of PLWHA belong to these states.[4] Oral diseases such as dental caries, periodontal disease, tooth loss, oral mucosal and oropharyngeal cancers, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS)-related oral disease and orodental trauma are major public health problems worldwide.[5] Dental caries though does not have any direct contact with the occurrence of HIV but caries activity may increase due to patient's neglect toward the oral health and also due to the side effects of the antiretroviral drug that causes xerostomia. Dry mouth as a result of decreased salivary flow rate may not only increase the risk of dental caries but also have a negative impact on quality of life because it leads to difficulty in chewing, swallowing, and tasting food.[5] Dental caries and HIV have been a much-neglected aspect. Very few studies have been reported, especially in India. Hence, we carried out an epidemiological study on HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral treatment (ART) for more than 1 year in an underdeveloped part of North Karnataka, Raichur.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Before the start of the study, ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Navodaya Dental College and Hospital, Raichur. Permission was also obtained from the Medical Superintendent of ART Center, Government Hospital, Raichur. A pilot study was carried out among thirty patients and based on the findings; the final sample size was calculated to 170. The inclusion criteria were individuals to be above 18 years of age and on ART for more than 1 year. Convenience sampling was followed. A written consent was obtained from all the participants. The dentition status and the treatment needs were recorded as per the WHO guidelines.[6] All the participants were provided with health education and referral to the Navodaya Dental College and Hospital, Raichur for treatment.

RESULTS

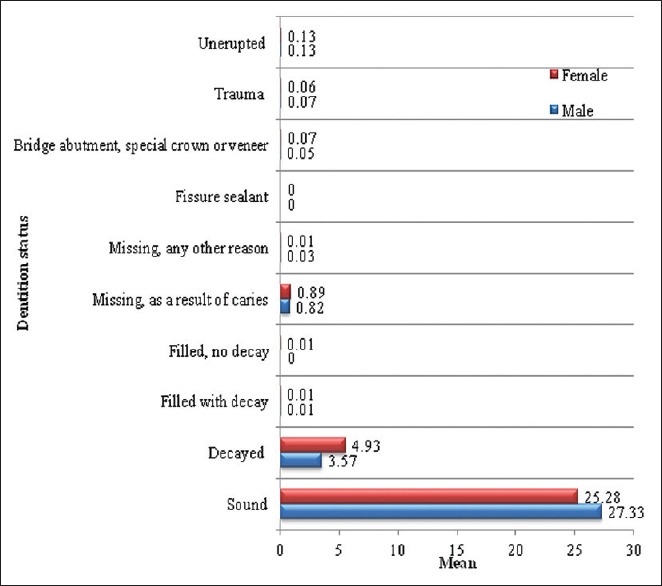

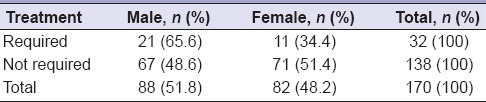

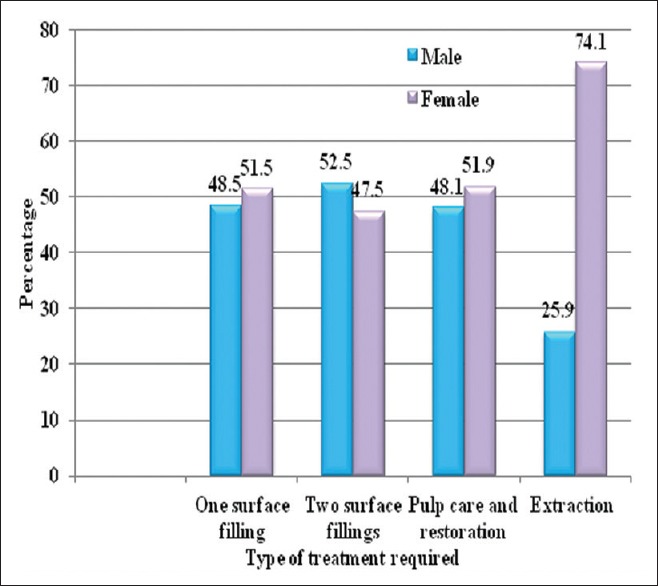

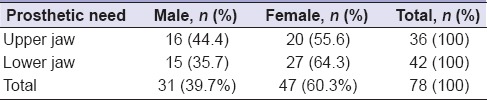

The mean age of the study population was 37.12 (±8.21), and their age ranged from 19 to 60 years. The total sample size was 170, of which 88 (51.8%) were male and 82 (48.2%) were females. The prevalence of dental caries was higher among the females than the males, and this was found to be statistically significant [Table 1]. The prevalence of dental caries was higher among the participants who used finger to clean their teeth compared to the toothbrush, neem stick, and charcoal users, and this was found to be statistically significant (χ2 = 13.81, df = 2, P = 0.001). There was no statistically significant association between the socioeconomic status, CD4 count, time since the patient was HIV positive, and the time since the patient was on ART with the prevalence of dental caries. There was also no correlation between the type, frequency, and the time of sugar consumption. Participants who had a sweet score of 15 or more (in the watch out zone) had higher dental caries than those with a sweet score of 10 (fair) and 5 (good), but this was not found to be statistically significant. Figure 1 shows the gender-wise distribution of the mean of the dentition status of the participants. Higher percentage of males required treatment than females [Table 2]. Those patients with a CD4 count of 350 or less required more treatment than those with a CD4 count of more than 350, and this was found to be statistically significant (χ2 = 5.916, df = 2, P = 0.05). On the whole, females required more treatments than the males [Figure 2]. A total of 132 (77.6%) HIV-positive patients did not require any prosthetic treatment of which, 73 (55.3%) were male and 59 (44.7%) were female. Among the rest 38 (22.4%) HIV-positive patients requiring prosthetic treatment, 15 (39.5%) were male and 23 (60.5%) were female. There was no association between the genders, socioeconomic status, the type of sugar consumed, frequency of sugar consumption, time of sugar consumption, the time duration since the participant was HIV positive, the CD4 count, and the treatment needs. Higher percentage of females needed prosthetic treatment in the Upper and lower jaw than males, but this was not statistically significant (χ2 = 0.6169, df = 1, P = 0.4322) [Table 3]. Only 39 (22.9%) HIV-positive patients had visited the dentist before, of which 17 (43.6%) were male and 22 (56.4%) were female. Among these, 66.7% had visited the dentist due to pain.

Table 1.

Gender-wise distribution of human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients based on the presence or absence of dental caries

Figure 1.

Gender-wise distribution of the mean of the treatment needs of the human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients

Table 2.

Distribution of the human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients based on the treatment need

Figure 2.

Gender-wise distribution of the study population based on their treatment needs

Table 3.

Gender-wise distribution of the human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients based on the need for prosthesis in relation to the upper or lower jaw

DISCUSSION

The present study was carried out in a rural set up of Raichur, the one of the most backward regions of the North Karnataka, India. The sample size was lesser than the study population involved in Johannesburg, South Africa (175),[7] and Argentina (200).[8] Nittayananta et al. reported 54.5% of cervical dental caries among HIV-positive patients in Thailand,[9] lesser than our study findings (79.4%). In the present study, 22.9% had visited a dentist before, higher than the findings of the study in Tanzania,[10] lesser than the findings of the study in America (97.8%),[11] and in Nepal,[12] (65.05%). This could be because the study set up in Raichur is one of the most backward developed places in North Karnataka, India. Ignorance of the people, lack of awareness regarding the importance of oral health, availability of the dental professional near the place of residence, and the affordability of the dental treatment could play a contributing role in this regard. Unlike the West, India is still laden with misnomers of HIV/AIDS and people's perception has not changed. This also could be an attributable factor in not reporting to the dentist since discrimination and neglect could be very much prevalent among these people. The participants felt that dental treatments were costly as well as time-consuming which could be major reasons for dental caries burden among this population. Compared to the findings of study in America,[11] where 18.8% visited the dentist because of pain, 66.7% in the present study visited the dentist due to the same. In addition only 2.6% of the present study population visited the dentist for prosthetic work, much lesser than the study in America (25.6%).[11] The prevalence of dental caries in the present study was 79.4%. It was much higher than the findings of study in Nigeria (25.0%)[13] and in Iran (54.0%).[14] We could not find any significant correlation between the CD4 count and dental caries unlike the study in Tamil Nadu, India[15] and in Iran.[14] In another study in Iran, there was no association between decayed, missing, and filled teeth among those treated with ART and those not on ART.[16]

The sampling frame of the patients on ART was not made available to us due to confidentiality issues by the government authorities, and it was not possible to follow a probability sampling technique. In addition, the patients under ART were not a regular visitors to the HIV center and reported only once a month to collect their drugs. Hence, this data should be interpreted with a lot of caution. But nevertheless, the data could definitely be a baseline data to formulate a comprehensive treatment plan for this special group.

CONCLUSION

In the present study, we found that the prevalence of dental caries was higher among females. It was statistically significant with the gender and the material used to clean the teeth. In addition, a high percentage of participants required treatment in one or the other form. We also found that as the CD4 count decreased, the treatment needs increased. Fewer patients had reported to the dentist due to cost and time barriers. As suggested by Demirbuga et al., the patient neglect their routine dentist control appointment or they go to the dentist only when they had pain.[17] It is essential to focus on specially formulated treatment plan for such special groups and have a better public–private partnership to practically imply it successfully.[18]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Khan SA, Moorthy J, Omar H, Hasan SS. People living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) and HIV/AIDS associated oral lesions; a study in Malaysia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:850. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sidibé M. UNAIDS Executive Director, Under Secretary, General of the United Nations, UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azodo CC, Ehizele AO, Umoh A, Ogbebor G. Preventing HIV transmission in Nigeria: Role of the dentists. Malays J Med Sci. 2010;17:10–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. NACO, Department of AIDS Control. Annual Report; 2011-2012 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day S, Ndiaye C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:661–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods. 4th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bajomo AS, Yusuf OA, Rudolph MJ, Tsotsi NM. Impact of oral lesions among South African adults with HIV/AIDS on oral health-related quality of life. J Dent Sci. 2013;8:412–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sánchez GA, D’Eramo LR, Lecumberri R, Squassi AF. Impact of oral health care needs on health-related quality of life in adult HIV positive patients. Acta Odontol Latinoam. 2011;24:92–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nittayananta W, Talungchit S, Jaruratanasirikul S, Silpapojakul K, Chayakul P, Nilmanat A, et al. Effects of long-term use of HAART on oral health status of HIV-infected subjects. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39:397–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00875.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahabuka FK, Petersen PE, Mbawala HS, Jürgensen N. General and oral health related behaviors among HIV positive and the background adult Tanzanian population. Oral Hyg Health. 2014;2:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox JE, Tobias CR, Bachman SS, Reznik DA, Rajabiun S, Verdecias N. Increasing access to oral health care for people living with HIV/AIDS in the U.S.: Baseline evaluation results of the Innovations in Oral Health Care Initiative. Public Health Rep. 2012;127(Suppl 2):5–16. doi: 10.1177/00333549121270S203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaunt F, Rai A, Kinkel HT. Assessment of the oral health status of healthcare-seeking adults living with HIV in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Oral Health Dent Manag. 2014;13:519–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amadi ES, Ngwu BA, Nwakpu KO, Ojong NA, Anyaele UP, Aballa AN, et al. Dental caries and oral lesions among HIV/AIDS patients in Enugu and Calabar towns in Nigeria. Nat Sci. 2012;10:21–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davoodi P, Hamian M, Nourbaksh R, Ahmadi Motamayel F. Oral manifestations related to CD4 lymphocyte count in HIV-positive patients. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2010;4:115–9. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2010.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasiraj GV. Correlation of CD4 count with dental caries in HIV seropositive individuals with and without ART (Antiretroviral Therapy) Open Access Sci Rep. 2012;1:442. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rezaei-Soufi L, Davoodi P, Abdolsamadi HR, Jazaeri M, Malekzadeh H. Dental caries prevalence in human immunodeficiency virus infected patients receiving highly active anti-retroviral therapy in Kermanshah, Iran. Cell J. 2014;16:73–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demirbuga S, Tuncay O, Cantekin K, Cayabatmaz M, Dincer AN, Kilinc HI, et al. Frequency and distribution of early tooth loss and endodontic treatment needs of permanent first molars in a Turkish pediatric population. Eur J Dent. 2013;7(Suppl 1):S99–104. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.119085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tak M, Nagarajappa R, Sharda AJ, Asawa K, Tak A, Jalihal S, et al. Prevalence of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment needs among 12-15 years old school children of Udaipur, India. Eur J Dent. 2013;7(Suppl 1):S45–53. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.119071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]