Abstract

Out-of-home mobility is a crucial prerequisite for autonomy and well-being. The European research project entitled Enhancing Mobility in Later Life: Personal Coping, Environmental Resources, and Technical Support (MOBILATE), funded within the European Commission’s Fifth Framework Programme, focused on older adults’ day-to-day mobility and the complex interplay between their personal resources and resources of their physical and social environments. A survey conducted in 2000 in urban and rural areas of five European countries (Finland, The Netherlands, Germany, Hungary and Italy) with various geographical, structural, and cultural conditions enabled us to compare patterns of older men’s and women’s actual mobility in different regional settings. The sample included n=3,950 randomly selected persons aged 55 years or older, stratified according to gender and age. Standardised questionnaires and a diary were used to assess the persons’ socio-structural, health-related, psychological and social resources as well as features of the community that may affect their options of realising outdoor oriented needs. The findings confirm that a person’s physical, economic, social and technical resources as well as the structural resources prevailing in the area in which he or she lives in are decisive preconditions of out-of-home mobility. Older persons living singly, women, persons with impaired health and low economic resources, and the rural elderly tend to be particularly at risk of losing their abilities to move about. We conclude that further support and stimulation for enhancing out-of-home mobility in later life must focus as much on transport policy measures as on appropriate social policy measures.

Keywords: Out-of-home mobility, Activities, Environment, Transport, Satisfaction

Introduction

In modern society mobility is not only a basic human need for physical movement. Due to the functional and spatial separation between the occupational, commercial and private spheres of life, of extensive suburban development and the establishment of commercial enterprises beyond residential areas it has become an ever more important prerequisite for participation in one’s natural, built, cultural and social environment. Empirical research has stressed the importance of outdoor mobility for the maintenance of independent living in old age. Mobility also promotes healthy ageing, delays the onset of disabilities, and postpones frailty, thereby contributing to subjective well-being and life satisfaction (e.g. Berlin and Golditz 1990; Heikkinen 1997; Ruuskanen and Ruoppila 1995; Spirduso and Asplund 1995). With advancing age, however, maintaining mobility may become jeopardised because of the increasing risk of physical and sensory impairments and in view of structural or environmental barriers. At the same time technological advances have opened up new opportunities for individual mobility and travel, also enhancing the ability to move about for persons with functional limitations. Hence the research theme of the European research project entitled Enhancing Mobility in Later Life: Personal Coping, Environmental Resources, and Technical Support (MOBILATE): the detailed analysis of out-of-home mobility in old age and the factors affecting it, is highly relevant for a ‘good life’ (Lawton 1983) for today’s and tomorrow’s ageing citizens.

This project, funded within the European Commission’s Fifth Framework Programme, focused on understanding the complex interplay between older adults’ personal abilities and resources and aspects of their physical and social environments. The basic goals of the project were (a) to provide a comprehensive description and explanation of older adults’ actual mobility behaviour, (b) to describe and explain individual change and constancy in mobility patterns as a function of chronological age, and (c) to determine whether new cohorts of older persons have different mobility patterns than older cohorts. The final goal was to identify how quality of life in old age depends on out-of-home mobility and on mobility-related personal and environmental factors. This study examined whether personal and structural characteristics can be used to differentiate groups among the elderly who differ in their out-of-home mobility and consequent satisfaction (for further project foci see Mollenkopf et al. 2002, 2003, 2004a, 2004b, 2004c; Ruoppila et al. 2003)

The data from the research project reflect diverse European realities in which today’s and tomorrow’s ageing takes place. Resources for mobility on the personal, environmental and technological levels are distributed very differently between European countries and also urban and non-urban regions within these countries. We therefore included in the investigation characteristic urban and rural areas from northern, southern and central European countries. Interest in cross-national research has increased in recent years, although comparative, especially interdisciplinary comparative, research constitutes a major challenge (e.g. Diener et al. 2003; Mayer 2004). Cross-national comparison may allow a better understanding of varying patterns of mobility and activities in different regional actualities.

Materials and methods

Geographical setting

The regions examined in the MOBILATE project study were: northern and southern Finland, The Netherlands, western and eastern Germany, Hungary, and Italy. These regions differ in geographic, climatic and structural conditions, settlement types, cultural traditions and welfare regimes. While population density in Finland outside urban areas is generally low and distances between settlements are long, in The Netherlands it is the highest in Europe. Car ownership is especially high in Italy and especially low in Hungary. Four of the MOBILATE countries are old EU member states: Finland representing the Nordic welfare state, Italy the southern European type and The Netherlands and Germany the continental/corporatist welfare regimes (see Esping-Andersen 1990, 1999). Hungary, a new member state of the European Union, belongs to the new transformational model (Makó and Keszi 2003; Chavance and Magnin 2000). In the case of this former communist country as well as in eastern Germany (the former German Democratic Republic) there has been a complete change of system, involving full transformation of the legal system, the ideology, economy, welfare policy, and institutional structure (Grabher 1995; Gyulavári 2000). In addition to differing environmental conditions, such economic and social differences may constitute important background conditions of older adults’ possibilities for moving about. Therefore this wider context should be kept in mind when interpreting the findings of a project which deals with older adults’ out-of-home mobility, transportation, health and activities.

Variables

From the perspective of environmental gerontology (e.g. Lawton 1983, 1998; Wahl 2001), out-of-home mobility can be regarded as a typical person-environment interaction. We therefore regarded out-of-home mobility as involving the person, transport modes, and social, natural and built environments, all of which interact with each other. Therefore we identified as many factors as possible that might explain differing mobility patterns. Individual factors pertaining to the person, such as age, gender, economic resources, health, cognition and personality were expected to explain a large proportion of mobility among older adults. In addition, variables describing the social context and social network were included in our research as well as variables describing the physical-spatial environment, such as living and neighbourhood conditions, the existence of and access to various services, the modes of transportation used to achieve out-of-home goals, and the outdoor activities in which the elderly are interested and participate. The interdisciplinary project was thus based on social sciences, psychology, the health sciences, environmental gerontology, and environmental or urban planning perspectives.

The different disciplinary traditions resulted in a number of problems that had to be solved concerning theoretical concepts and methodological approaches. Moreover, many of the crucial concepts, although often used, could not be easily defined in a multicultural context, such as concepts of socio-economic and educational background, health, leisure, social network, and quality of life.

Out-of-home mobility, the core focus in the MOBILATE project, was understood as a complex phenomenon and therefore conceptualised as a comprehensive construct. In line with sociological approaches considering mobility in the context of societal modernisation processes (Burkart 1994; Knie 1997; Lash and Urry 1994; Rammler 1999), we argue that in modern society mobility is associated with important values such as freedom, autonomy and flexibility. The assessment of out-of-home mobility of men and women living in modern societies should therefore include as much as possible of these aspects. Going beyond the usual approach in traffic planning and research, that is, measuring mobility by the number of trips and journeys that persons make, we additionally included the variety of transport options used and the diversity of outdoor activities performed in our analyses.

Figure 1 describes this concept in terms of the general project structure. It shows also the main assessed aspects in the MOBILATE study, the follow-up (data collected of persons first investigated in the 1995 Outdoor Mobility Survey; see Mollenkopf et al. 2004c) and the final outcome, namely quality of life of older adults.

Fig. 1.

The MOBILATE model of outdoor mobility

Research design

A survey was conducted in 2000 in urban and rural areas of the five European countries listed above. In view of the diverging national conditions, no uniform standard was imposed when selecting suitable cities and rural areas. Instead, to consider the specific national peculiarities we chose middle-sized cities in proportion to each country’s characteristics, as we also did with villages or rural areas characteristic of the respective country.

The sample included n=3,950 persons aged 55 years or older, randomly selected from the municipality’s population register or by random route procedure, and disproportionately stratified according to gender and age (55–74 years vs. 75 years or over, with approximately equal numbers of men and women in each group). Stratification was carried out to obtain cell sizes sufficiently large for detailed analyses, which would not have been possible with a proportional sampling. To correct for oversampling towards older persons and males, all descriptive and comparative analyses were performed with weighted data.

About 55% of the net sample of eligible participants were interviewed by experienced, specially trained interviewers. In most countries (exception: eastern Germany) the net response rate was higher in the rural (58%) than in the urban areas (about 52%). The drop-out rate was lowest in rural Italy (18.6%) and highest in urban The Netherlands (65.8%). The main reasons for dropping out were simple refusal (22.6%), having no time (6.2%), not being reachable (5.4%); as only 5.1% gave health reasons, we believe that the sample does not show a strong bias towards very healthy respondents.

Standardised questionnaires were used in face-to-face interviews to assess the persons’ socio-structural, health related, psychological, and social resources and features of the community that may affect their options of realising outdoor needs. If available, internationally acknowledged measures were employed. For reasons of brevity the indicators used here are characterised in detail in the respective sections and tables.

The extent of out-of-home mobility, both that by foot and that by any other means of transportation, was assessed by mobility diaries in which the respondents documented their trips per day over the course of 2 days (the day before and after the interview). This enabled us to compare patterns of the subjects’ day-to-day mobility, their personal resources, and the environmental conditions prevailing in the areas where they live in.

The broad scope of the variables for assessing out-of-home mobility in the different regions resulted in a large data set. We tested all mean differences for statistical significance. Below we select some crucial aspects of out-of-home mobility in the areas studied and then examine characteristic connections between mobility and socio-demographic, health-related, psychological and structural variables to distinguish subgroups of older persons who differ in mobility and satisfaction. This enables us to identify groups that are particularly at risk of losing their ability to move about.

Results

Trip making of the elderly

Trip making is an important aspect of mobility and contributes to the well-being of older persons (Carp 1988; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2001). About two-thirds (77%) of the study participants made at least one trip during the 2 days. Women made on average fewer trips than men and urbanites fewer than rural dwellers. Urban men aged 55–74 years made the most trips a day (2.5) and rural women aged 75 years or over the fewest (1.1). Some 90% of the trips concerned simple trips, i.e. from home and back home.

Walking is the most common mode of older adults. In 45% of all trips walking was at least one of the modes. Driving (28%) or riding in (11%) a car was the second mode, followed by cycling (10%) and public transport (8%). Hungary has most walkers (58%) and Italy most car drivers (42%). In urban areas more destinations are within walking distance than in the rural areas, where the car is used relatively often. Up to 15% of subjects use the bicycle in topographically favourable areas in Finland, Hungary and The Netherlands. Most drivers were those with few problems related to activities of daily living (ADL), men, not using public transport and aged 55–74 years. Women go more by foot or by public transport. With walking as the main transport mode the distance was rather small: 40% of the trips in urban areas and 46% in rural areas covered less than 1 km.

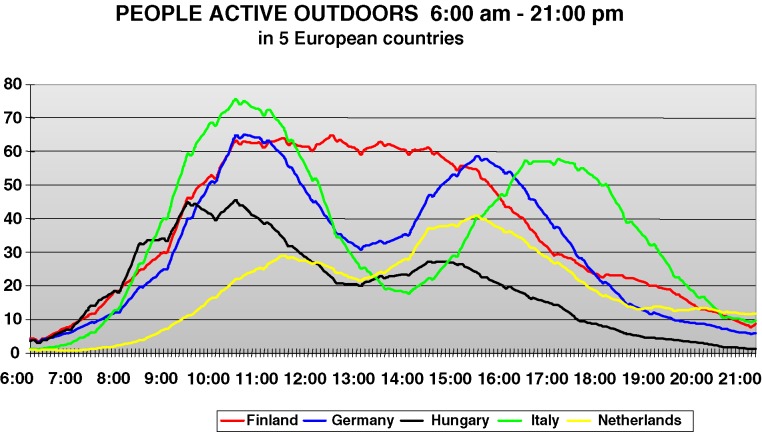

The time of the day of trip making is important for traffic management. Figure 2 shows this aspect in the percentages of persons active outside their homes between 6 a.m. and 9 p.m. The local culture, related to the climate, seems to be decisive for the differences that were found (e.g. compare the patterns in Finland and Italy). ‘Shopping’ and ‘attending services’ are the most common morning activities while ‘visiting’ and ‘recreation’ are more frequent in the afternoon. After 8 p.m. only few persons leave their homes.

Fig. 2.

Persons active outdoors 6:00 a.m.–21:00 p.m. in five European countries

Among urban populations the Finns and Italians were most satisfied regarding their mobility in this survey of the elderly (mean 8.5 and 8.1, respectively, on a scale of 0–10). In rural areas the most satisfied were the Finns (8.1) and the Dutch (7.8). The older age cohort was generally less satisfied than the younger, and rural women the least satisfied of all (for more details see Mollenkopf et al. 2002). Compared with these figures, satisfaction with public transport is low, particularly in rural areas (mean 4.9 in Italy, 6.6 in eastern Germany and Hungary). Those living in cities use more public transport than those living in rural areas. The greater availability there may be the principal explanation. A second reason may concern their physical condition. One needs fairly good bodily condition to access the stops, to enter and exit the vehicles, and to make the trip. Thus among those in the oldest groups ‘walking’ is often the only effective possibility.

Health

Health may be the most important resource affecting outdoor mobility. With ageing, motor control declines, including sensorimotor changes, generalised slowing, decrements in balance and gait, neuro-anatomical reductions, muscular changes, and reduced proprioception (Ketcham and Stelmach 2001). Some elderly persons have such difficulty with mobility that they have no alternative but to stay at home although they wish to go out. Our data suggest that many older persons want to be more often mobile outdoors and participate in leisure activities but are unable to do so because their physical mobility is poor (Mollenkopf et al. 2002). Mobility, especially in certain kinds of physical activities, also effects on health. To analyse how the different aspects of health are associated with out-of-home mobility, health was operationalised by the ability to perform heavy ADL, light ADL, satisfaction with health, visual acuity and visuomotor coordination. This overall health variable was analysed in relation to the mean number of journeys per day, mobility-related attitudes towards traffic and the number of holiday trips lasting at least 1 week. Regardless of the mobility indicator the health-related variables explained the greatest part of the variance. The same age-associated changes which affect relationships between health and out-of-home mobility also affect the relationship between health and leisure. With age and decreasing health the number of leisure activities as well as their frequency decreases. Individuals with better health showed higher satisfaction with the possibility of participating in various leisure activities.

Housing and built environment

The characteristics of the built and local environment are important factors in mobility. Environmental-theoretical approaches suggest that the complex causal relationship between an older person and the environment is mutual, and that the less competent an individual is, the greater the impact of environmental factors on the individual (Lawton 1986). Thus disability affects not only the person but also the exchange between the person and the environment (Verbrugge and Jette 1994).

The home, especially after retirement, is the principal environment. There were evident differences in the regions studied. The level of infrastructure in Hungarian homes—especially in the rural area—is much lower than in homes in western Europe, while the proportion of home ownership is the highest in Hungary. Home ownership is especially low in the both eastern and western German cities.

Services in the living area are very important for maintaining an autonomous life in old age. With the exception of Finland most of the subjects in this survey reported good availability and access within 15 min to the services which they rate as important: food store, pharmacy, physician and (except for Hungary and Italy) bank. In all of the regions investigated the most frequently used mode of transport to reach services is one’s own feet. The car is fundamental in Italy, especially in the rural areas. The bicycle is used most in Hungary, followed by eastern Germany, Finland and The Netherlands. Public transport is little used, both in urban and in rural areas. The elderly in Hungary have the greatest difficulty reaching services. Although only a minority report having difficulty reaching services, it is interesting to note that the reasons impeding access are principally those related to health. Also, great distances were considered a difficulty in both the cities and the rural areas.

Familiarity with the area and feeling safe can also influence out-of-home mobility for the elderly. Security is generally not a concern for most respondents, although the feeling of being secure generally decreases with age. Older persons in Finland feel most secure. The greatest insecurity was found in the Hungarian countryside. Italians generally feel less secure than the Dutch, Finns and Germans.

Social network resources

The social context can be both a stimulus and a form of support for mobility. Living alone constitutes one of the basic aspects of social relationships (Wagner et al. 1999). In this regard there are wide differences between the regions in this study. The proportion of single households is the lowest in Italy (18%) and exceeds 30% in western Germany, The Netherlands, Finland and Hungary. Comparing rural and urban areas, it is only in Hungary that the proportion of elderly living alone is higher in the countryside than in the cites. Regarding trip-making behaviour, however, there were no differences between persons living alone and those living with others. Nonetheless, the social context obviously influences out-of-home mobility in the elderly: those without persons living outside the household who are important to them for emotional or personal reasons (e.g. relatives, good friends, neighbours, district nurse) made fewer trips than people with a diversified social network (1.8 vs. 2.2 trips a day). These important others who lived within the immediate neighbourhood were reached mainly by foot in all regions studied. If they lived further away than 15 min, they were most often reached by car, except in Hungary where cars are less available. The closer the person lives to important others, the more frequently they met. Health or the availability of a car did not affect the frequency of personal contact. However, health impairments and lack of a car were most often responsible for problems in maintaining social contacts. Moreover, the distance caused problems in meeting important others, especially in rural Finland where the distances between locations are very great.

Identifying the ‘high-mobility’ and ‘low-mobility’ groups

The above findings confirm that a person’s physical, social, and technical resources as well as the structural resources of the local region are decisive prerequisites of out-of-home mobility. However, these are only the basic preconditions for moving about. Further variables such as a person’s motives for making trips, the importance assigned to going out and psychological variables such as control beliefs and visuomotor coordination are also important. [To assess cognitive and affective environmental bonding participants were asked to indicate importance on an 11-point Likert-type scale from 0, absolutely not important, to 10, very important. Motivational environment-related attitude towards the indoor vs. the outdoor home environment was assessed with a global self-rating of being an indoor-/outdoor-type of person (staying at home vs. being on the go as much as possible; H. Mollenkopf, F. Oswald, H.-W. Wahl, unpublished). Aspects of self-perception may influence outdoor mobility in a variety of ways. For example, the experience of being in control over one’s life circumstances may strongly motivate an ageing individual to invest much time and effort in maintaining a maximum level of out-of-home mobility. [The instrument administered in the MOBILATE survey was the control beliefs questionnaire used in the Berlin Aging Study (Baltes et al. 1999; J. Smith, M. Marsiske, H. Maier, unpublished), which assesses the dimensions of ‘internal control’ (six items), ‘external control: powerful others’ (four items) and ‘external control: chance’ (four items).] Similarly, both high internal control beliefs and a high motivation for being on the go may override adverse environmental aspects even when confronted with health decrements. Perceptual motor processing or visuomotor coordination (Oswald and Fleischmann 1995; Wechsler 1958) has repeatedly been found to be a major indicator of basic cognitive functioning, frequently described in the literature as fluid intelligence or the mechanics of intelligence (e.g. Baltes 1993). This cognitive ability is also an important ability underlying outdoor mobility related cognitive functioning. [Basic cognitive abilities in terms of perceptual motor processing or visuomotor coordination and working memory were assessed with the subtest provided in the Nuremberg Age Inventory (Oswald and Fleischmann 1995)].

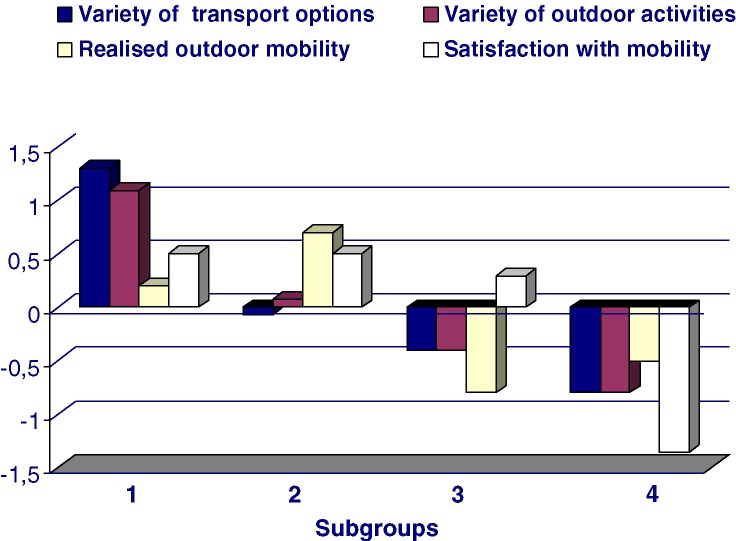

We therefore examined characteristic connections between mobility, on the one hand, and socio-demographic, psychological, and structural variables, on the other, to identify subgroups who differ in mobility. For this we carried out a cluster analysis based on our model of mobility including three major indicators of outdoor mobility as determining variables: (a) day-to-day mobility (number of trips as reported in the diaries), (b) variety of transport options (range of modes used; standardised range 0=immobile to 1=use of all modes that had been asked for), (c) the variety of motives for undertaking outdoor activities (range of performed options; standardised 0=no outdoor activity to 1=all activities assessed pursued), and as a further variable we included (d) satisfaction with one’s mobility (range 0=not satisfied at all to 10=very satisfied), because a high extent of mobility does not necessarily result in high satisfaction. Instead, persons with limited mobility in terms of few trips, low use of transport modes, and only few or no outdoor activities might be equally satisfied—at least according to theories suggesting disengagement (Cumming and Henry 1961) or selective optimisation with compensation (Baltes and Baltes 1990) in old age. Low satisfaction, however, is considered to indicate that persons suffer from personal or environmental mobility restrictions and need support for improving their possibilities of moving about. Analyses were performed using the SAS 8e software FASTCLUS and CLUSTER procedures, with Ward’s clustering algorithm. Using Z-standardised scores of both the three mobility indicators and global mobility satisfaction as input variables, four clearly distinct clusters of outdoor mobility emerged (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Four groups of outdoor mobility in old ageMOBILATE Survey 2000. Subgroup 1 High outdoor mobility/high mobility satisfaction; subgroup 2 medium outdoor mobility/high mobility satisfaction; subgroup 3 low outdoor mobility/still satisfied with mobility; subgroup 4 low outdoor mobility/unsatisfied with mobility. All scores Z standardised (mean 0, SD 1) to facilitate comparison

Clusters were further examined with respect to socio-demographic, health-related, psychological and structural variables (Table 1). The first group had the highest mobility scores in terms of transport modes used, range of outdoor activities and satisfaction with mobility. The frequency of trips in this group was also clearly above average. This highly mobile and highly satisfied group consisted mainly of the ‘young’ elderly, men, healthy and better educated persons, and active car drivers. The second group showed the highest level of actual day-to-day mobility and was as satisfied with their mobility as the first group, although their use of transport modes and the variety of their outdoor leisure activities were clearly lower. Satisfaction with one’s financial situation and the level of education (total number of years) were lower as well, but still on par with the average or even slightly higher. Satisfaction with mobility was still in the positive score range of the third group as well. All components of mobility were, however, clearly lower than in the two first groups. Members of this group exhibit the beginnings of frailty, indicating the need for preventive efforts to avoid further loss in outdoor mobility. Finally, the fourth group was the counterpart to the first one: All of the scores lie in the negative range of values, with a particularly pronounced negative score regarding satisfaction with mobility. Interestingly, the narrow range of outdoor mobility of this subgroup (i.e. number of trips made) was higher than in the third group, but the use of transport means and range of outdoor leisure activities were clearly the lowest of all groups. This group consisted mainly of the ‘older’ elderly, women, singly living persons, and those with the least education, greatest health impairments, and most restricted financial situation. Not surprisingly, only about every tenth person drove a car while the proportion of persons who used a car only as a passenger and/or persons without a car in the household was highest in this group.

Table 1.

Subgroups of outdoor mobility in old age: subgroup 1 high outdoor mobility/high mobility satisfaction, subgroup 2 medium outdoor mobility/high mobility satisfaction, subgroup 3 low outdoor mobility/still satisfied with mobility, subgroup 4 low outdoor mobility/unsatisfied with mobility (means, percentages) (Source: MOBILATE Survey 2000, n=3934)

| Subgroup 1 (n=887) | Subgroup 2 (n=1,320) | Subgroup 3 (n=792) | Subgroup 4 (n=951) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic variables | ||||

| Age (years) | 65.2 | 66.5 | 70.2 | 73.5 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 48.2% | 48.5% | 38.7% | 31.4% |

| Female | 51.8% | 51.5% | 61.3% | 68.6% |

| Household size | ||||

| Lives alone | 23.4% | 24.0% | 27.0% | 44.0% |

| Lives with others | 76.6% | 76.0% | 73.0% | 56.0% |

| Satisfaction with financesa | 7.5 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 5.7 |

| Educationb (years) | 11.8 | 10.0 | 8.8 | 8.0 |

| Car use (%) | ||||

| No car in household | 20.3% | 33.9% | 46.7% | 68.5% |

| As passengers | 12.4% | 17.0% | 25.7% | 20.4% |

| As driver | 67.3% | 49.1% | 27.6% | 11.0% |

| Health-related variables | ||||

| Physical mobilityc | 3.9 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 2.6 |

| Satisfaction with healthd | 7.4 | 6.9 | 6.4 | 4.8 |

| Psychological variables | ||||

| Working memorye | 36.7 | 30.6 | 26.7 | 20.7 |

| Control beliefs, powerful othersf | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.9 |

| Indoor-outdoor-typeg | 5.2 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 3.5 |

| Importance of being outh | 8.4 | 7.9 | 7.5 | 6.0 |

| Geographic variables | ||||

| Region | ||||

| Urban | 65.7% | 49.3% | 41.2% | 39.9% |

| Rural | 34.3% | 50.7% | 58.8% | 60.1% |

| Country (%; rank order) | ||||

| 1 | Netherlands | E. Germany | E. Germany | Hungary |

| 2 | Finland | Italy | W. Germany | Italy |

| 3 | W. Germany | W. Germany | Netherlands | W. Germany |

| 4 | E. Germany | Hungary | Hungary | E. Germany |

| 5 | Italy | Finland | Italy | Netherlands |

| 6 | Hungary | Netherlands | Finland | Finland |

aAssessed on an 11-point scale (0=completely unsatisfied; 10=completely satisfied)

bTotal length of education

cAssessed on a 5-point scale (1=very bad; 5=very good)

dAssessed on an 11-point scale (0=completely unsatisfied; 10=completely satisfied)

eTest score (range 0–67)

fSubscale items assessed on a 5-point scale (1=not agree at all; 5=fully agree)

gAssessed on an 11-point scale (0=like being indoor best; 10=like being outdoor best)

hAssessed on an 11-point scale (0=not important at all; 10=very important)

Psychological variables also differed between the groups. Visuomotor coordination clearly and consistently decreased from the first to the fourth group, while external control beliefs increased. In addition, indoor orientation increased from the highly mobile and satisfied to the almost immobile and dissatisfied group, whereas the importance of going out substantially decreased.

With regard to regional differences, the rural elderly were more frequently found in the low mobility groups. In terms of countries, the risk groups described above tend to be represented more strongly by older adults from Hungary and Italy, while the Dutch and Finnish elderly were found predominantly in the ‘high-mobility group. Separate analyses for each country are needed to better understand the positive and negative conditions influencing out-of-home mobility of each country’s elderly.

Discussion

The findings of the MOBILATE project presented here confirm that a person’s physical, economic, social, and technical resources, as well as the structural conditions of the region he or she lives in, are decisive prerequisites of out-of-home mobility in old age. Further variables such as a person’s motives for making trips, the importance assigned to going out, psychological variables and cognitive abilities, also play a substantial role for moving about. Unfortunately, these preconditions for mobility do not apply equally for all ageing European citizens. There were clear differences, for example, between those living in urban and rural areas. Low satisfaction scores indicated that those suffering from personal or environmental mobility restrictions need support for improving their ability to get around. In all countries satisfaction was lower in rural areas, except in The Netherlands and western Germany. In Italy and western Germany public transport in the countryside was evaluated particularly negatively. In Hungary, persons living in rural areas did not feel they had adequate opportunities for pursuing leisure activities, and in eastern Germany both urban and rural respondents bemoaned the lack of services and facilities. These evaluations clearly indicate a discrepancy between that which the persons want or need and that which is available to them.

The situation was better in the cities studied. Essential services such as grocery, pharmacy, physician and public transportation were accessible within 15 min for more than 85% of older adults living in urban areas. This means, however, that at least one in seven persons aged 55 years or older could not reach basic facilities. Moreover, 15 min can constitute a serious problem for persons who are mobility impaired and cannot rely on a car. The greater reliance on walking than other modes among the oldest groups refutes the view that the elderly switch to public transport after ceasing to drive a car (Rosenbloom 2003).

The seriousness of these problems was confirmed by the results of the MOBILATE follow-up assessment of urban elders. Particularly the Finnish (and to a lesser extent the Italian and German) men and women experienced changes in the accessibility and/or transport connections to the services of the cities where they lived. The changes reported during the period 1995–2000 reflect the closing down of or diminished access to shops and services. A clear finding from every city was that perceived negative change in personal access to services explained both the reduction in transport modes used and the reduced range of various outdoor activities (Mollenkopf et al. 2003). The importance of overcoming barriers in both public and private areas is becoming clear due to the increase in the size of the elderly population (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 1996).

Many factors make it difficult to forecast future developments. Major historical changes such as economic depressions, scientific-technological innovations and sweeping changes in legislation may affect the life course and ageing. If current societal trends continue, the mobility conditions of persons reaching retirement age will improve in many respects. However, future studies on out-of-home mobility in later life need to consider differences in the scope available to older adults. We found characteristic connections between mobility and socio-demographic, psychological and structural variables and identified subgroups of persons who differ in their mobility patterns.

Furthermore, our findings confirm the existence of specific groups deserving special attention with regard to stimulation, prevention, intervention and rehabilitation. Singly living older persons, women, persons with impaired health and low economic resources, and rural older adults tend to be particularly at risk of losing their ability to move about. An accumulation of unfavourable conditions, as is the case among a considerable proportion of the elderly European population, requires immediate intervention and social as well as technical support measures. Persons exhibiting the beginnings of frailty or decreasing sensory abilities need preventive efforts to avoid further loss in outdoor mobility. Persons with moderate outdoor mobility and satisfaction in spite of a limited range of transport modes and outdoor activities deserve attention and stimulation to enhance or maintain their out-of-home mobility, whereas the younger, healthy persons and active car drivers seem able to cope very well with their needs in terms of mobility and activity.

Thus specific focus group programmes for the prevention, intervention and rehabilitation of mobility impairment must be developed and implemented for persons at risk. Further support and stimulation must also focus on transport policy measures and appropriate social policy measures. For older men and women who have no social, economic or technical resources at their disposal for overcoming personal or environmental limitations it is crucial to create flexible, user-centred options for mobility that offer a genuine alternative to both the private automobile and traditional local public transport services.

This study was limited to specific urban and rural areas in each country, and response rate varied between research sites. Therefore further separate and specific analyses for each region are needed to better understand the specific positive and negative conditions influencing the out-of-home mobility of each country’s older citizens. It is not only necessary to know their personal resources but also to consider the societal and environmental conditions prevailing in the respective region and country in which they live in to achieve the goal of enhancing older people’s out-of-home mobility according to their individual needs.

References

- Baltes MM, Freund AM, Horgas AL (1999) Men and women in the Berlin Aging Study. In Baltes PB, Mayer KU (eds) The Berlin aging study. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 259–281

- Baltes Gerontologist. 1993;33:580. doi: 10.1093/geront/33.5.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes Z Padagogik. 1990;35:85. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:612. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkart Soziale Welt. 1994;45:216. [Google Scholar]

- Carp F (1988) Significance of mobility for the well-being of the elderly. In: Committee for the study on improving mobility and safety for older people (ed) Transportation in an aging society. Special report 218. TRB, Washington

- Chavance B, Mangin E (2000) National trajectories of post-socialist transformation: is there convergence towards Western capitalism? In: Dobry M (ed) Democratic and capitalist transitions in eastern Europe. Kluwer, Dordrecht, pp 221–233

- Cumming E, Henry WE (1961) Growing old, the process of disengagement. Basic Book, New York

- Diener Ann Rev Psychol. 2003;54:403. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G (1990) The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press, Princeton

- Esping-Andersen G (1999) Social foundations of post-industrial economies. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Grabher G (1995) The elegance of incoherence: economic transformation in East Germany and Hungary. In: Dittrich EJ, Schmidt G, Withley R (eds) Industrial transformation in Europe. Sage, London, pp 33–53

- Gyulavári T (2000) Az Európai Únió szociális dimenziója [Social dimension of the European Union]. Szociális és Családügyi Minisztérium, Budapest

- Heikkinen E (1997) Background, design and methods of the project. In: Heikkinen E, Heikkinen RL, Ruoppila I (eds) Functional capacity and health of elderly people—the Evergreen Project. Scand J Soc Med [Suppl] 53:1–18 [PubMed]

- Ketcham CJ, Stelmach GE (2001) Age-related declines in motor control. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW (eds) Handbook of the psychology of aging. Academic, New York, pp 313–348

- Knie Soziale Welt. 1997;47:39. [Google Scholar]

- Lash S, Urry J (1994) Economies of signs and space. Sage, London

- Lawton Gerontologist. 1983;23:349. doi: 10.1093/geront/23.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP (1986) Environment and aging. CSA, Albany

- Lawton Environment and. 1998;aging:theory. [Google Scholar]

- Makó C, Keszi R (2003) eWork in EU candidate countries. Report 396. Institute for Employment Studies, Brighton

- Mayer KU (2004) Life courses and life chances in a comparative perspective. In: Svallfors S (ed) Analyzing inequality: life chances and social mobility in comparative perspective. Stanford University Press, Stanford

- Mollenkopf Gerontechnology. 2002;1:231. [Google Scholar]

- Mollenkopf Enhancing outdoor mobility in later. 2003;life:personal. [Google Scholar]

- Mollenkopf Hallym Int J Aging. 2004;6:1. [Google Scholar]

- Mollenkopf H, Marcellini F, Ruoppila I, Tacken M (eds) (2004b) Ageing and outdoor mobility. A European study. IOS, Amsterdam

- Mollenkopf H, Ruoppila I Marcellini F (2004c). Always on the go? Older people’s outdoor mobility today and tomorrow. In: Wahl H-W, Tesch-Römer C, Hoff A (eds) Emergence of new person-environment dynamics in old age: a multidisciplinary exploration. Baywood, Amityville

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (1996) Caring for frail elderly people. Policies in evolution. Social policy studies no 19. OECD, Paris

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2001) Ageing and transport. Mobility needs and safety issues. OECD, Paris (available at: http://oecdpublications.gfi-nb.com/cgi-bin/OECDBookShop.storefront/655091789/)

- Oswald WD, Fleischmann UM (1995) Nürnberger-Alters-Inventar (NAI). [The Nuremberg Age Inventory, NAI]. Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen-Nuremberg

- Rammler S (1999) Die Wahlverwandtschaft von Moderne und Mobilität—Vorüberlegungen zu einem soziologischen Erklärungsansatz der Verkehrsentstehung [Affinity between modernity and mobility-considering a sociological explanation of the emergence of traffic]. In: Buhr R, Canzler W, Knie A, Rammler S (eds), Bewegende Moderne. Fahrzeugverkehr als soziale Praxis. Sigma, Berlin, pp 39–71

- Rosenbloom The mobility needs of older. 2003;Americans:implications. [Google Scholar]

- Ruoppila I, Marcellini F, Mollenkopf H, Hirsiaho N, Baas S, Principi A, Ciarrocchi S, Wetzel D (2003) The MOBILATE cohort study 1995–2000: enhancing outdoor mobility in later life. The differences between persons aged 55–59 years and 75–79 years in 1995 and 2000. DZFA research report no 17. German Centre for Research on Ageing, Heidelberg

- Ruuskanen Age Ageing. 1995;24:292. doi: 10.1093/ageing/24.4.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirduso Quest. 1995;47:395. [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner M, Schütze Y, Lang FR (1999) Social relationships in old age. In: Baltes PB, Mayer KU (eds) The Berlin aging study. Aging from 70 to 100. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 282–301

- Wahl H-W (2001) Environmental influences on aging and behavior. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW (eds) Handbook of the psychology of aging, 5th edn. Academic, San Diego, pp 215–237

- Wechsler D (1958) The measurement and appraisal of adult intelligence. Williams Wilkins, Baltimore