Abstract

Background

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common inflammatory skin disease, but treatment options for moderate-to-severe disease are limited. Ustekinumab is an IL-12/IL-23p40 antagonist that suppresses Th1, Th17 and Th22 activation, commonly used for psoriasis patients.

Objective

We sought to assess efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in moderate-to-severe AD patients.

Methods

In this phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 33 patients with moderate-to-severe AD were randomly assigned to either ustekinumab (n=16) or placebo (n=17), with subsequent crossover at 16wks, and last dose at 32wks. Background therapy with mild topical steroids was allowed to promote retention. Study endpoints included clinical (SCORAD50) and biopsy-based measures of tissue structure and inflammation, using protein and gene expression studies.

Results

The ustekinumab group achieved higher SCORAD50 responses at 12wks, 16wks (the primary endpoint), and 20wks compared to placebo, but the difference between groups was not significant. The AD molecular profile/transcriptome showed early robust gene modulation, with sustained further improvements until 32wks in the initial ustekinumab-group. Distinct and more robust modulation of Th1, Th17 and Th22 but also Th2-related AD genes was seen after 4wks of ustekinumab treatment (i.e. MMP12, IL-22, IL-13, IFN-γ, elafin/PI3, CXCL1, CCL17; p<0.05). Epidermal responses (K16, terminal differentiation) showed faster (4wks) and long-term regulation (32wks) from baseline in the ustekinumab-group. No severe adverse events were observed.

Conclusions

Ustekinumab had clear clinical and molecular effects, but clinical outcomes might have been obscured by a profound “placebo” effect, most likely due to background topical glucocorticosteroids and possibly insufficient dosing for AD.

Keywords: Ustekinumab, atopic dermatitis, IL-12, IL-23, p40, IL-22

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common chronic inflammatory skin disorder. Recent data suggest that AD is primarily immune-driven, like psoriasis, showing dense cellular infiltrates (1) and over-expression of certain cytokines in skin lesions (2). While psoriasis is Th17-centered, AD is strongly Th2/Th22 skewed, with some Th1 and Th17 contributions (3–5). However, the extent at which all these components contribute to the actual AD phenotype remains unclear. Whereas psoriasis has experienced rapid development of targeted therapeutics, that also helped to define it as an IL-23/Th17 disease (6), specific therapeutics are not yet available for AD patients, and most tested agents are directed towards the Th2 axis (7, 8).

Both acute and chronic AD lesions are associated with increased mRNA levels of IL-22 and IL-17 cytokines and associated products, including S100A7/8/9, PI3/elafin and CXCL1 (8). In AD lesions, mRNA expressions of the p40 cytokines IL-12 and IL-23 show similarly up-regulated and even higher levels than in psoriasis tissues (9). Interestingly, p40 and IL-23R have also been found to be significantly up-regulated in non-lesional AD skin (9).

Ustekinumab blocks the cytokines IL-12 and IL-23 by targeting the common p40 subunit shared by these cytokines, thereby inhibiting Th1 and Th17/Th22 responses, respectively (10). Ustekinumab has become widely used in psoriasis patients (11), where it profoundly decreases skin inflammation (12). Several case reports have suggested beneficial clinical effects of ustekinumab in severe AD patients (13–16), while some others show a partial or no effect (17, 18). Importantly, controlled trials are lacking.

We hypothesized that ustekinumab would suppress IL-22 production via p40 blockade in AD patients, with reversal of the epidermal growth/differentiation defects and underlying immune activation, subsequently improving clinical disease activity.

We thus performed a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover designed, phase II study to investigate the safety and efficacy of ustekinumab in 33 patients with moderate-to-severe chronic AD over a 40 week period. Due to the debilitating nature of AD and to promote patient retention, background therapy with the low-potency (class VI) topical steroid triamcinolone acetonide (0.025%) cream was provided throughout the study.

Methods

Patients

Eligible patients were 18–75 years old (Table 1 and Table S1), with a diagnosis of chronic moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (SCORAD ≥15), which could not be managed with conventional therapy. Patients previously treated with any agent blocking IL-12 or IL-23, current malignancy or autoimmune disease, a history of malignancy (except adequately treated or excised basal/squamous cell carcinoma of the skin), or evidence of active or latent infection were excluded.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| Baseline Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Placebo-Ustekinumab | Ustekinumab-Placebo | p-value | |

| Sex | Male | 10 | 10 | 1.00 |

| Female | 6 | 6 | ||

| Race | Asian | 2 | 1 | 1.00 |

| African American | 2 | 4 | ||

| White | 12 | 11 | ||

| Age | 40 | 37 | 0.62 | |

| IgE Status | Intrinsic | 4 | 4 | 1.00 |

| Extrinsic | 12 | 12 | ||

| Severity Score | Mean SCORAD | 69.73 | 65.40 | 0.467 |

| Biomarkers | Mean IgE (U/mL) | 9,422 | 7,443 | 0.69 |

| Mean eosinophils % | 9.43 | 6.83 | 0.08 | |

Study design

This was a phase II, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded single center study (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01806662) to investigate safety and efficacy of ustekinumab treatment in moderate-to-severe AD patients. Patients underwent 1:1 randomization using a computer generated subject randomization table by an unblinded pharmacist. to Subjects received subcutaneous ustekinumab or placebo at weeks 0, 4, and 16 with a crossover to the other agent (either ustekinumab or placebo) at weeks 16, 20, and 32 (Figure 1A) to ensure patient retention. Thus, each patient received three doses of ustekinumab during the study, as on week 16, each patient received two injections (both ustekinumab and placebo) – one to complete the first part of the study, and a second reflecting the crossover design. Dosing of ustekinumab followed the recommendations for psoriasis, namely 45mg and 90mg per injection for patients weighing ≤100kg or >100kg, respectively. Background therapy of triamcinolone 0.025% cream BID was given to the patients starting at week 0 to promote patient retention. The average amount of GCS cream given to each patient was 1.53 (+/− 0.83) and 1.19 (+/− 0.83) pound jars in the placebo-ustekinumab and in the ustekinumab-placebo group, respectively. Although patients in the initial placebo group requested a higher number of GCS jars, differences were not statistically significant among treatment arms.

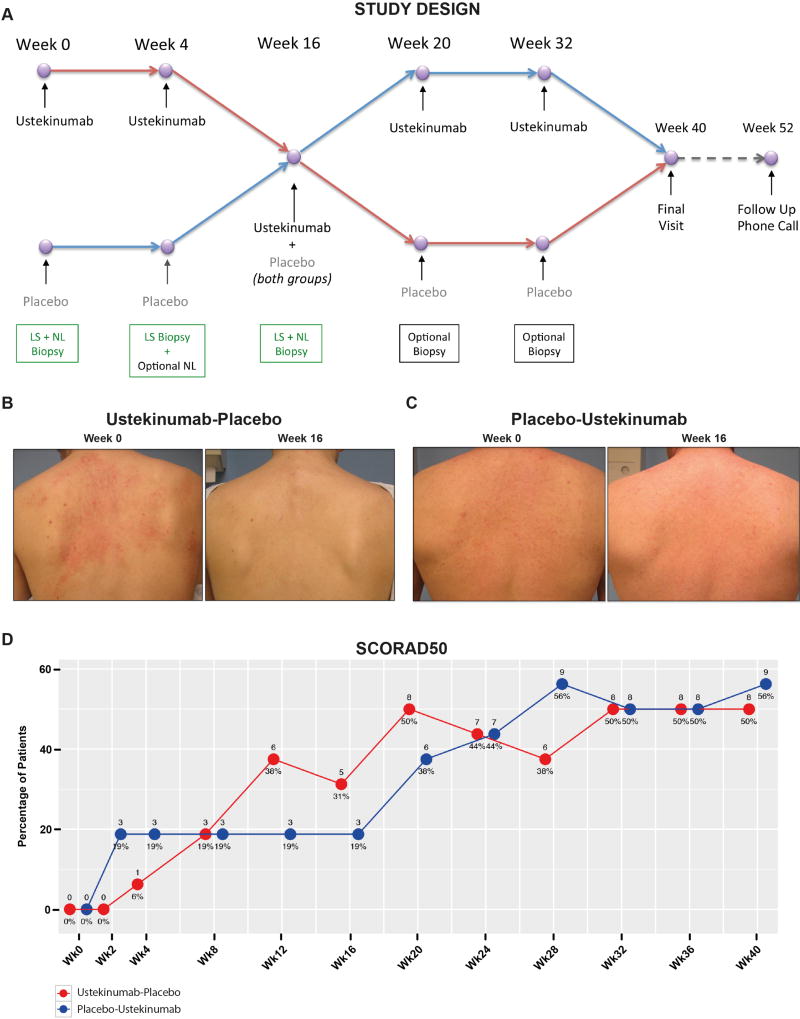

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of the study design; (B-C) representative clinical images at baseline/BL and 16wks in both treatment arms; (D) percentage of SCORAD50 responses in each treatment arm (last observation carried forward after week 4); numbers above each time point represent absolute numbers of patients reaching SCORAD50 responses.

The primary and secondary clinical endpoints were a 50% or greater percentage decrease from baseline objective SCORAD (SCORing of Atopic Dermatitis) at week 16 or 32, respectively. Patients were evaluated for clinical responses and for quality of life every 2–4 weeks until week 40, using SCORAD and DLQI (Dermatology Life Quality Index), respectively. A follow up phone call at week 52 concluded the study. After week 52, patients who achieved a SCORAD50 response at any time point during the study were then qualified to receive another ustekinumab dose to participate in a 12 week open-label extension phase.

Subjects that withdrew from the study before completing four weeks (and a lesional biopsy at 4 weeks) were considered treatment failures. For subjects that dropped out after this time point, the last visit was considered as our primary endpoint (last observation carried forward).

A subgroup analysis on responses to background therapy in the placebo group (until week 16) has been reported in a separate publication (19).

The study was conducted in accordance with current United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations and guidelines, the European Clinical Trials Directive and associated guidelines, International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guidelines on Good Clinical Practice (GCP), the principals of the Declaration of Helsinki, as well as all other applicable national and local laws and regulations. All participants provided written informed consent under an IRB approved protocol.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) stainings were performed on frozen cryostat tissue sections using purified mouse anti-human mAbs, as previously described (20, 21). Epidermal thickness was quantified using computer-assisted image analysis software (ImageJ 1.42; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Quantitative real-time PCR and gene-array analysis

RNA was extracted, followed by hybridization to Affymetrix Human U133Plus 2.0 gene arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) or quantitative RT-PCR/TLDA, as previously described (19, 20) (Table S2).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were carried out in R Bioconductor packages.

The primary endpoint of this study was the proportion of subjects who achieved an improvement of 50% or greater from their baseline objective SCORAD (SCORAD50) at 16wks. SCORAD50 responses (at each timepoint) and frequencies of AE between the two treatment arms were compared using Fisher’s Exact Test. SCORAD50 proportions are presented along with the exact 95% confidence interval. Changes in SCORAD, serum IgE, and serum eosinophils (%) were assessed with a mixed-effect model (Fixed-factors: treatment and time, random intercept for each patient). Similar models were used for IHC and (log2-transformed) qRT-PCR/TLDA measurements (hARP normalized) but adding tissue (LS/NL) and its interaction with time as a fixed-factor.

Quality control of microarray chips was carried out using standard QC metrics and R package microarray quality control. Images were scrutinized for spatial artifacts using Harshlight (22). Expression measures were obtained using GCRMA algorithm (23). A batch effect - corresponding to the hybridization date - was detected by PCA and adjusted using ComBat function from R’s sva package. Probe sets with at least 5 samples, expression values >3, and SDs >0.15 were kept for further analyses. Expression values were modeled using mixed-effect models, with treatment and time as fixed factor, and a random effect for each patient. FCHs for the comparisons of interest were estimated, and hypothesis testing was conducted with contrasts under the general framework for linear models in the R limma package. P values from the moderated (paired) t tests were adjusted for multiple hypotheses using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Hierarchical clustering was performed with Euclidean distance and a McQuitty agglomeration scheme (21, 23).

Results

Patients

The design of this placebo-controlled crossover study is shown in Figure 1A. 35 moderate-to-severe AD patients were screened, and 33 enrolled in a 1:1 randomization in two treatment arms (Table S3). One patient from the placebo-ustekinumab group was retrospectively excluded from analyses due to initial misdiagnosis. One patient was excluded from tissue analyses due to quality control issues, and one patient dropped out already by week 2 and was therefore not included in tissue analyses. Demographics and baseline characteristics were not different between groups (ustekinumab-placebo and placebo-ustekinumab) (Table 1 and Table S1). 27 patients completed visits through 16wks, while 21 patients completed all required visits through week 40. Although 16 patients qualified for another single dose of ustekinumab in the open label extension at week 52, only 6 patients enrolled.

Safety

There were no serious adverse events (SAE) reported in the study. 14 patients experienced a total of 24 AE (all self-reported), which were classified as being mild or moderate (Table S4). There were no significant differences in AE frequency between treatment arms. No patient discontinued the study due to AE, but 2 patients were excluded from analyses after week 28 due to newly developed contact dermatitis and due to worsening skin infection (eczema herpeticum), respectively. There were no AE reported in the open label extension phase.

Clinical outcomes

Representative clinical pictures are shown in Figures 1B-C. Similar mean SCORADs of 65.40 and 69.73 (p=0.47) were noted at baseline in the ustekinumab-placebo and placebo-ustekinumab groups, respectively (Table 1). Mean levels of SCORAD and DLQI (Figure S1A-B) profoundly decreased from baseline through 40wks in both arms, with a tendency of lower SCORADs in the ustekinumab-placebo group before 8wks and after 16wks. Figure 1D illustrates the percentage of patients that attained a SCORAD50 response in both treatment groups, which was neither significantly different at 16wks (primary endpoint; OR 1.93, 95%CI 0.30–15.33) nor at 32wks of treatment (secondary endpoint; OR 1.00, 95%CI 0.20–4.93) between the two treatment arms. Nevertheless, responses in the placebo group were relatively flat between 2wks and 16wks, while the ustekinumab-treated group had increasing SCORAD50 responders through 20wks. Subsequently, responses decreased at 16 and 28wks, being 8–12wks after the last ustekinumab injection. Yet, SCORAD50 responses increased and remained stable across weeks 32–40 without a subsequent ustekinumab dose. While changes in mean SCORAD from baseline were significant in both groups (Figure S1A), the difference between groups was not statistically significant. Still, the ustekinumab group achieved higher SCORAD50 responses at both weeks 12 and 16 than placebo, but did not reach a level of statistical significance in the comparison with placebo. Similar effects were also observed in the second part of the study. Stable SCORAD50 responses on placebo until 16wks showed rapid improvements following ustekinumab crossover at 16wks, peaking at 28wks (8wks following 2nd ustekinumab injection). Thus, SCORAD50 data in both groups suggest that the response was optimal 8 weeks after administration of a ustekinumab dose. In addition, SCORAD75 responses showed a trend of increased treatment responses beginning with week 20 in the initial ustekinumab group, with waning effects after week 28 (Figure S1C). The initial placebo group, by contrast, showed low and relatively stable responses until week 32, and a surge in responses thereafter (Figure S1C). These data, although not statistically significant, suggest that a SCORAD75 response can be achieved by a subset of patients after three ustekinumab injections.

Tissue responses to treatment

To further characterize ustekinumab treatment responses, we assessed lesional and nonlesional biopsies from patients, and stratified for both clinical and histological responses. Clinical response was defined by our primary endpoint, SCORAD50 response at 16wks, and histological response was defined as a decrease in epidermal thickness (Figure S2A) as well as a resolution of K16 protein staining (Figure S2B) at 16wks. While at 16wks, we found similar rates of histologic resolution in both arms, at 4wks, 50% (8/16) of ustekinumab-treated patients reversed K16 expression in lesions, while only 29% (4/14) placebo patients achieved this response (Figure S2B). This early epidermal effect of ustekinumab was also reflected by a more significant reduction of K16 mRNA (Figure S2C) and a tendency of lower epidermal thickness (Figure S2D) at this time point. Using histological response classification, all clinical non-responders were also histological non-responders in the ustekinumab-placebo group (Figure S2E), suggesting that our criteria of histological response reflect clinical activity. Comparing histological responders and non-responders in the ustekinumab-placebo group, we found that all clinical responders continued to improve clinically far beyond their last ustekinumab dose at 16wks (arrow; Figure S2F), in contrast to histological non-responders.

Gene profiling shows more rapid and sustained responses with ustekinumab

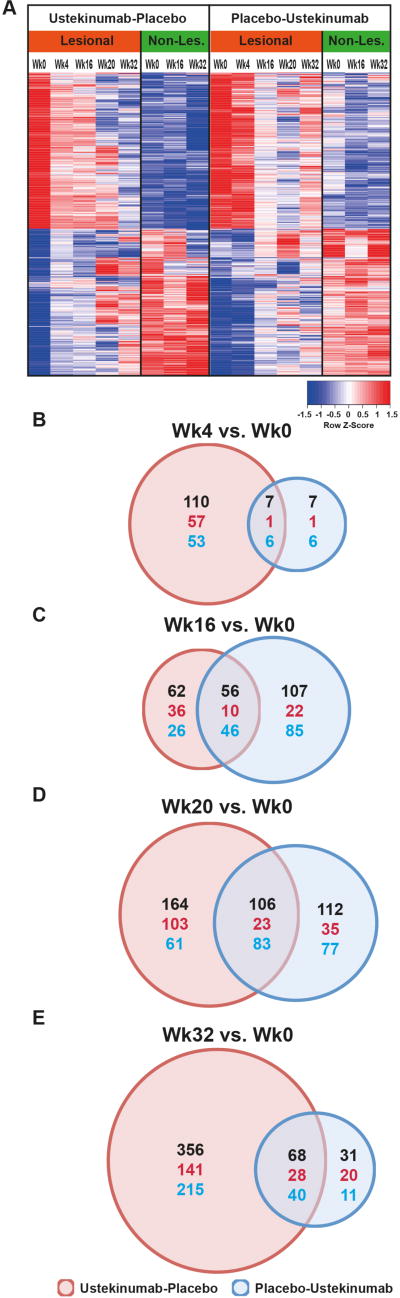

Gene-arrays were performed to define the AD transcriptome (differentially expressed genes/DEGs in lesional versus non-lesional skin at baseline; criteria of FCH>1.5, FDR<0.05; Table S5) (21, 24), and to assess the effect of ustekinumab on the transcriptome. The heatmap in Figure 2A shows mean expression levels of transcriptomic genes in both treatment arms. While baseline/wk0 levels were similar among groups, a strong treatment effect was observed only in the ustekinumab group by 4wks, while the placebo group largely remained stable. Improvements in the transcriptome (red to blue and blue to red transitions) at 20wks, and even more so at 32wks, were much more evident in the ustekinumab-placebo group, again suggesting a long-term therapeutic effect of ustekinumab. We also assessed the number of transcriptome genes that were significantly modulated from baseline over the course of the study, as shown in Figure 2B-E. At 4wks, 117 DEGs from baseline were noted in the ustekinumab arm (Figure 2B), compared to only 14 DEGs in the placebo group. While this difference was lost by 16 and 20wks of treatment (Figure 2C-D), at 32wks most genes (424/780) were differentially expressed in the ustekinumab-placebo group, but only 99 in the placebo-ustekinumab arm (Figure 2E). Importantly, differentially expressed genes between the two groups showed little overlap at 16wks, suggesting distinct treatment effects by ustekinumab and by “placebo”, i.e. background triamcinolone treatment only.

Figure 2.

(A) Mean expression levels of DEGs of the AD transcriptome; (B-E) Venn diagrams depicting the number of transcriptomic DEGs significantly changed from baseline at the depicted timepoints; black: total number, red: increase, blue: decrease of DEGs.

Immune gene-subset profiling

As AD is a cytokine-mediated disease (8), we assessed changes from baseline in a previously defined immune-gene subset in lesional and non-lesional skin (criteria: FCH>2 and p<0.05; Figure S3). Stronger, and more significant decreases were seen in mRNA expressions at 4wks in the ustekinumab group. These included general inflammation, T-cell, Th2, and Th17 markers (MMP12, CX3CR1, CCL19, CCL17, PI3/elafin, lipocalin 2/LCN2). Sustained, significant decreases in immune genes at 32wks were more prominent in the ustekinumab-placebo group, including markers of general inflammation (MMP12), T-cells (GZMB), IL-22/IL-17-induced S100As, Th2-attracting chemokines (CCL17, CCL18), Th1 (OASL) and Th17-related products (CXCL1).

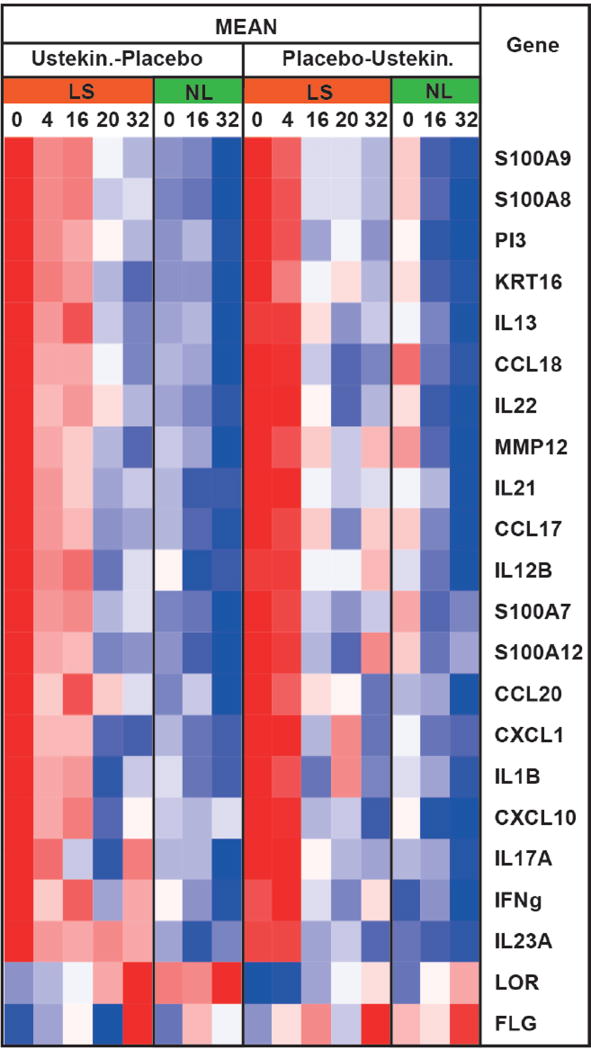

qRT-PCR assessments

To validate microarray findings, and to evaluate primary Th1, Th2, Th17, Th22 cytokines and terminal differentiation markers, which are often below detection levels on gene-arrays (25), we performed qRT-PCR. Results are shown in a heatmap in Figure 3, as fold changes (FCH) from baseline in Figure S4 and as individual graphs in Figure S5. Consistent with the primary targets of ustekinumab, IL-12 and IL-23, we found Th1 (IL12B/IL-12/IL-23p40, CXCL10, IFN-γ, Figure S5A-C) and Th17/IL-23-related genes (IL-23A/IL-12p19, CCL20, CXCL1, PI3/elafin, IL-21, Figure S5E-I) to be significantly downregulated at 4wks only in ustekinumab-treated patients. Similar reductions were observed in Th22/IL-22 (Figure S5J) and several Th17/Th22-related genes (S100As, Figure S5K-N). By 4wks, ustekinumab treatment also showed decreases of Th2 cytokines (CCL17, CCL18, IL-13, Figure S5O-Q), which are not primary targets of ustekinumab. Differences between ustekinumab and placebo were less evident after 4wks (Figures 3, S4 and S5). Epidermal responses showed stronger modulations at 32wks in the ustekinumab group, as evidenced by large decreases in K16 (Figure S2C).

Figure 3.

Heatmap summary of mean mRNA expression levels in lesional/LS and non-lesional/NL AD skin (qRT-PCR).

Discussion

We assessed efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in moderate-to-severe AD patients, with continuous background topical steroid therapy in both treatment arms to enhance patient retention. Endpoints of the study included clinical and histologic/mechanistic measures at weeks 16 and 32, as well as assessments at other time points. Ustekinumab has unique mechanistic effects in AD as early as 4wks of treatment. The kinetics of the response suggest, that the strongest anti-inflammatory effects already occur within 4–8 weeks following an ustekinumab dose, with waning efficacy thereafter. The attenuated responses observed after >8wks from ustekinumab dosing at both 16 and 32wk endpoints might possibly explain the obscured differences in clinical efficacy between ustekinumab and placebo groups. Consistently, a relatively high drop out rate was observed in our study, mostly attributed to lack of treatment efficacy.

Nevertheless, detailed genomic profiling does show a clear effect of ustekinumab that is distinguishable from background steroid treatment after only 4wks of ustekinumab dosing (4 and 20wks in the ustekinumab-placebo and the placebo-ustekinumab arm, respectively). Strong, rapid modulation of expected Th1, Th17 and Th22 pathway genes could be observed. While based on the historic Th1/Th2 models (26), one might have predicted that Th1 inhibition would exacerbate Th2 responses, the ustekinumab arm also showed significantly higher inhibition of key Th2-related products at week 4. This is consistent with data from mouse models that indicate that IL-23 signaling might modulate Th2 T-cell differentiation (27), and findings from flaky tail mice suggesting that the IL-17 pathway is, at least partly, involved in IL-4 signaling (28). While it has long been assumed that the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T-cells into lineages is an irreversible endpoint, recent data suggest a profound plasticity of CD4+ T-cell differentiation in the context of human immune responses (29), substantiated by the finding that single human T-cell clones contributed to both Th17 and Th2 lineages (30).

This study also presents several limitations: 1) A clear limitation is that the study has been designed a few years ago without knowledge of pharmacokinetics or drug durability in AD patients, and therefore, psoriasis dosing intervals (31) were chosen; 2) We also failed to appreciate the magnitude of systemic inflammation in moderate-to-severe AD patients, which is significantly larger than in psoriasis, as evidenced by the observation that T cells, particularly in the peripheral blood, show much stronger signs of activation in AD than in psoriasis as assessed by ICOS expression, a marker of T cell activation (32, 33). This hyperactivation in moderate-to-severe AD patients might lead to accelerated clearance of target-bound ustekinumab and/or the need for either higher or more frequent dosing of ustekinumab in this disease. This is also supported by a recent report of a severe, recalcitrant AD patient that has been treated effectively with much shorter intervals of ustekinumab given every 8wks (16). 3) The treatment effect might be partially masked due to use of background topical GCS. In this study, treatment with a class VI low-potency GCS formulation led to profound effects in the placebo, and possibly also in the treatment arm, an effect that is particularly evident after the 4wks time point in placebo-treated patients. For this reason, we advocate to avoid “add-on” topical GCS in AD trials, as even after several weeks of application, topical GCS do not lead to a stable disease phenotype, as recently described (19). Nevertheless, although profoundly improving disease activity as measured by SCORAD, our data show that the use of background GCS in the placebo arm modulated different genes than with ustekinumab treatment. This was best visible at 16wks, when despite small differences observed in clinical disease activity between the two treatment arms, only few DEGs were shared between the two groups. We must also point out that although it becomes increasingly evident that monotherapy trials with systemic medications for moderate-to-severe AD can be successfully conducted for a few months and are able to highlight the unique benefits of the study drug (34, 35), our trial was designed at a time when it seemed impossible to keep patients with significant disease on placebo alone; 4) Another weakness of this study was clearly that at 16wks, both treatment arms received the active drug, so the primary endpoint is not able to assess for the last dose of ustekinumab in the ustekinumab-placebo arm. Indeed, at 20wks (4wks from last dose) we can detect the maximal clinical efficacy as well as major molecular and cellular suppression with ustekinumab. 5) Additionally, while the cross-over design is helpful with patient retention, it possibly blurs the ustekinumab effects in the second half of the study. 6) Another limitation of this study is that both Th1 and Th17 immune axes are inhibited by ustekinumab, which prevents individual assessment of their potential role in the disease phenotype (5, 7, 36–38). Th1 responses have long been described as present particularly in chronic AD patients (37, 39), while increased Th17 responses were found in acute AD (40, 41). Stronger IL-23/Th17 skewing was described in intrinsic AD compared to extrinsic AD patients (42). Noda et al. have recently showed that the Th17 axis is strongly activated in in Asian AD patients, suggesting that this phenotype harbors some psoriasis-like features (36). Thus, ustekinumab might be more effective in patients with intrinsic or Asian AD, which favors more personalized treatment approaches for different AD phenotypes.

Unlike psoriasis that is Th17-centered, recent findings suggest that the AD phenotype cannot be explained by a single cytokine pathway (7, 36, 42–44). Clinical trials with IL-23/IL-17, IL-22, and IL-4/IL-13 cytokine antagonism (coupled with mechanistic studies) are needed to shed light on the relative contribution of each axis to the disease phenotype. The results of this study establish likely contribution of p40 cytokines (IL-12, IL-23) to inflammatory pathways in AD. However, future studies need to establish pharmacokinetics of ustekinumab in AD patients and may need to be conducted without the confounding effects of concomitant topical steroids.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded by a research grant from Janssen Pharmaceutical to EGY and JGK. PMB and MSF were supported in part by grant # UL1 TR00043 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program.

JGK has received research support (grants paid to his institution) and/or personal fees from Pfizer, Amgen, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Kadmon, Dermira, Boehringer, Innovaderm, Kyowa, BMS, Serono, BiogenIdec, Delenex, AbbVie, Sanofi, Baxter, Paraxel, Xenoport, and Kineta. EGY is a board member for Sanofi Aventis, Regeneron, Stiefel/GlaxoSmithKline, MedImmune, Celgene, Anacor, AnaptysBio, Celsus, Dermira, Galderma, Glenmark, Novartis, Pfizer, Vitae and Leo Pharma; has received consultancy fees from Regeneron, Sanofi, MedImmune, Celgene, Stiefel/GlaxoSmithKline, Celsus, BMS, Amgen, Drais, AbbVie, Anacor, AnaptysBio, Dermira, Galderma, Glenmark, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Vitae, Mitsubishi Tanabe and Eli Lilly; and has received research support from Janssen, Regeneron, Celgene, BMS, Novartis, Merck, LEO Pharma and Dermira. MSF has received research support from Pfizer and Quorum Consulting.

Footnotes

RF, SRC, MSF, JGK and EGY contributed to research design, SK, JFD, XZ, XL, KMB, NK, IsC, InC, PG and MSW were involved in the acquisition of data, and PMB, SG, MO, RD, MSF, JGK and EGY were involved in analysis and interpretation of data. All authors were involved in drafting the paper and/or revising it critically, and all authors approved the submitted final version.

Disclosures: The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Guttman-Yassky E, Lowes MA, Fuentes-Duculan J, Whynot J, Novitskaya I, Cardinale I, et al. Major differences in inflammatory dendritic cells and their products distinguish atopic dermatitis from psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(5):1210–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nograles KE, Zaba LC, Shemer A, Fuentes-Duculan J, Cardinale I, Kikuchi T, et al. IL-22-producing "T22" T cells account for upregulated IL- in atopic dermatitis despite reduced IL-7-producing TH17 T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(6):1244–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Czarnowicki T, Krueger JG, Guttman-Yassky E. Skin barrier and immune dysregulation in atopic dermatitis: an evolving story with important clinical implications. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(4):371–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guttman-Yassky E, Nograles KE, Krueger JG. Contrasting pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis--part II: immune cell subsets and therapeutic concepts. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(6):1420–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eyerich K, Novak N. Immunology of atopic eczema: overcoming the Th1/Th2 paradigm. Allergy. 2013;68(8):974–82. doi: 10.1111/all.12184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim J, Krueger JG. The immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33(1):13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noda S, Krueger JG, Guttman-Yassky E. The translational revolution and use of biologics in patients with inflammatory skin diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(2):324–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mansouri Y, Guttman-Yassky E. Immune Pathways in Atopic Dermatitis, and Definition of Biomarkers through Broad and Targeted Therapeutics. J Clin Med. 2015;4(5):858–73. doi: 10.3390/jcm4050858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suarez-Farinas M, Ungar B, Noda S, Shroff A, Mansouri Y, Fuentes-Duculan J, et al. Alopecia areata profiling shows TH1, TH2, and IL-3 cytokine activation without parallel TH17/TH22 skewing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(5):1277–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaghi D, Krueger GG, Callis Duffin K. Ustekinumab: a review in the treatment of plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(2):160–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowes MA, Suarez-Farinas M, Krueger JG. Immunology of psoriasis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:227–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reddy M, Torres G, McCormick T, Marano C, Cooper K, Yeilding N, et al. Positive treatment effects of ustekinumab in psoriasis: analysis of lesional and systemic parameters. J Dermatol. 2010;37(5):413–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agusti-Mejias A, Messeguer F, Garcia R, Febrer I. Severe refractory atopic dermatitis in an adolescent patient successfully treated with ustekinumab. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25(3):368–70. doi: 10.5021/ad.2013.25.3.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puya R, Alvarez-Lopez M, Velez A, Casas Asuncion E, Moreno JC. Treatment of severe refractory adult atopic dermatitis with ustekinumab. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(1):115–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez-Anton Martinez MC, Alfageme Roldan F, Ciudad Blanco C, Suarez Fernandez R. Ustekinumab in the treatment of severe atopic dermatitis: a preliminary report of our experience with 4 patients. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105(3):312–3. doi: 10.1016/j.adengl.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shroff A, Guttman-Yassky E. Successful use of ustekinumab therapy in refractory severe atopic dermatitis. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1(1):25–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samorano LP, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL, Leshem YA. Inadequate response to ustekinumab in atopic dermatitis - a report of two patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(3):522–3. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wlodek C, Hewitt H, Kennedy CT. Use of ustekinumab for severe refractory atopic dermatitis in a young teenager. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/ced.12847. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brunner PM, Khattri S, Garcet S, Finney R, Oliva M, Dutt R, et al. A mild topical steroid leads to progressive anti-inflammatory effects in the skin of patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1323. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tintle S, Shemer A, Suarez-Farinas M, Fujita H, Gilleaudeau P, Sullivan-Whalen M, et al. Reversal of atopic dermatitis with narrow-band UVB phototherapy and biomarkers for therapeutic response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(3):583–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suarez-Farinas M, Tintle SJ, Shemer A, Chiricozzi A, Nograles K, Cardinale I, et al. Nonlesional atopic dermatitis skin is characterized by broad terminal differentiation defects and variable immune abnormalities. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(4):954–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suarez-Farinas M, Pellegrino M, Wittkowski KM, Magnasco MO. Harshlight: a "corrective make-up" program for microarray chips. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:294. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Z, Irizarry R, Gentleman R, Martinez-Murillo F, Spencer F. A Model-Based Background Adjustment for Oligonucleotide Expression Arrays. J Am Stat Assoc. 2004;99(468):909–17. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamilton JD, Suarez-Farinas M, Dhingra N, Cardinale I, Li X, Kostic A, et al. Dupilumab improves the molecular signature in skin of patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(6):1293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suarez-Farinas M, Lowes MA, Zaba LC, Krueger JG. Evaluation of the psoriasis transcriptome across different studies by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) PloS One. 2010;5(4):e10247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novak N, Leung DY. Advances in atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23(6):778–83. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng J, Yang XO, Chang SH, Yang J, Dong C. IL-23 signaling enhances Th2 polarization and regulates allergic airway inflammation. Cell Res. 2010;20(1):62–71. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakajima S, Kitoh A, Egawa G, Natsuaki Y, Nakamizo S, Moniaga CS, et al. IL-17A as an inducer for Th2 immune responses in murine atopic dermatitis models. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(8):2122–30. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou L, Chong MM, Littman DR. Plasticity of CD4+ T cell lineage differentiation. Immunity. 2009;30(5):646–55. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Becattini S, Latorre D, Mele F, Foglierini M, De Gregorio C, Cassotta A, et al. T cell immunity. Functional heterogeneity of human memory CD4(+) T cell clones primed by pathogens or vaccines. Science. 2015;347(6220):400–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1260668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao Z, Carter C, Wilson KL, Schenkel B. Ustekinumab dosing, persistence, and discontinuation patterns in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(2):113–20. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2014.883059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Czarnowicki T, Malajian D, Shemer A, Fuentes-Duculan J, Gonzalez J, Suarez-Farinas M, et al. Skin-homing and systemic T-cell subsets show higher activation in atopic dermatitis versus psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(1):208–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Czarnowicki T, Gonzalez J, Shemer A, Malajian D, Xu H, Zheng X, et al. Severe atopic dermatitis is characterized by selective expansion of circulating TH2/TC2 and TH22/TC22, but not TH17/TC17, cells within the skin-homing T-cell population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(1):104–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beck LA, Thaci D, Hamilton JD, Graham NM, Bieber T, Rocklin R, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(2):130–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thaci D, Simpson EL, Beck LA, Bieber T, Blauvelt A, Papp K, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical treatments: a randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):40–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noda S, Suarez-Farinas M, Ungar B, Kim SJ, de Guzman Strong C, Xu H, et al. The Asian atopic dermatitis phenotype combines features of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with increased T17 polarization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(5):1254–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gittler JK, Shemer A, Suarez-Farinas M, Fuentes-Duculan J, Gulewicz KJ, Wang CQ, et al. Progressive activation of T(H)2/T(H)22 cytokines and selective epidermal proteins characterizes acute and chronic atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(6):1344–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kabashima-Kubo R, Nakamura M, Sakabe J, Sugita K, Hino R, Mori T, et al. A group of atopic dermatitis without IgE elevation or barrier impairment shows a high Th1 frequency: possible immunological state of the intrinsic type. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;67(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387(10023):1109–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00149-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toda M, Leung DY, Molet S, Boguniewicz M, Taha R, Christodoulopoulos P, et al. Polarized in vivo expression of IL-11 and IL-17 between acute and chronic skin lesions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(4):875–81. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koga C, Kabashima K, Shiraishi N, Kobayashi M, Tokura Y. Possible pathogenic role of Th17 cells for atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(11):2625–30. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suarez-Farinas M, Dhingra N, Gittler J, Shemer A, Cardinale I, de Guzman Strong C, et al. Intrinsic atopic dermatitis shows similar TH2 and higher TH17 immune activation compared with extrinsic atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(2):361–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leung DY, Guttman-Yassky E. Deciphering the complexities of atopic dermatitis: shifting paradigms in treatment approaches. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(4):769–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Czarnowicki T, Esaki H, Gonzalez J, Malajian D, Shemer A, Noda S, et al. Early pediatric atopic dermatitis shows only a cutaneous lymphocyte antigen (CLA)(+) TH2/TH1 cell imbalance, whereas adults acquire CLA(+) TH22/TC22 cell subsets. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(4):941–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.