Abstract

Objective

To determine the frequency of patients seeking oral health advice and willingness of community pharmacists to provide oral health information in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study with sample size (n = 332) of randomly selected community pharmacists across the province. The questionnaire comprised of 25 questions divided into 3 sections. Frequency distributions of different categorical variables were calculated and Pearson's chi-square tests were performed to compare categorical variables. Statistical significance was determined at p-value <0.05%. SPSS version 22 was used for statistical analyses.

Results

Of the 332 pharmacists, 279 agreed to participate in the study, yielding a response rate of 84%. About 71% of pharmacists provided less than 30 oral health advices and 29% of them gave ≥30 oral health advices daily. Oral ulcer (64.2%), dental pain (59.5%) and bleeding gums (54.5%) were the three most common oral conditions encountered by the pharmacists. More pharmacists (90%) were approached for advice about tooth whitening products, tooth brush and mouth wash in large cities compared with 66.7% of pharmacists in small cities of the province. Lack of interaction with dental professionals was recognized the most important barrier to providing oral health services to the clients. Almost one third (35.8%) had formal oral health training in their undergraduate program and only 26.5% of them were always confident in providing oral health advices. Majority (93.5%) of respondents recognized their important role in providing oral health advices and 98.2% were enthusiastic to provide oral health information.

Conclusions

Community pharmacists are approached frequently for oral healthcare advices. Majority of them had no oral health training. Almost all of them were willing to provide oral health information in the community. It is essential to provide continuous oral health education to the pharmacists to better serve oral health needs of the community.

Keywords: Community pharmacist, Oral health advice, Oral problems, Saudi Arabia

1. Introduction

The practice of community pharmacists has developed over the years from traditional dispensing of medicine to more profound public and professional involvement in health care which is valuable to the community (Amien et al., 2013). General healthcare system considers the community pharmacists as healthcare advisers, preventers, promoters and educators (Mann et al., 2015). It was reported that about 26.5% of respondents considered the pharmacist as their first choice of healthcare provider, and in the case of emergency, approximately 37% of respondents identified the pharmacist as their first choice of healthcare provider (Sello et al., 2012).

Various factors contribute to the active role played by the community pharmacies in healthcare system as they are situated in important geographical locations which enable the public an easy access to healthcare professionals and offer minimal time and effort for symptomatic relief without hospital appointments and fees (Anderson, 2007, Steel and Wharton, 2011). In Saudi Arabia, lack of time and difficulty in scheduling appointments with physicians or dentists were the main reasons people seek care from pharmacists (Abou-Auda, 2003).

Oral problems may indicate unfortunate consequences (Macpherson et al., 2003). The most common oral health complaints for which community pharmacists are approached include oral ulcers, toothache, gingival bleeding and loose dentures. Less frequently consulted oral health-related issues are teething problems, mouth rinse choices, and selection of toothbrush and toothpastes (Amien et al., 2013). However, the benign conditions of many oral lesions, such as oral thrush and oral ulcers, lead many individuals to avoid the dentist visit and head toward the community pharmacist to instantly relieve the symptoms (Amien et al., 2013). A recent study in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia reported that 69.7% of consumers were comfortable in seeking oral health advice from the pharmacist, 10.6% did not feel comfortable, and 9.2% did not have a chance to ask for an advice (Bawazir, 2014). Therefore, community pharmacists have an important role in recognizing and managing a wide variety of oral health conditions and diseases (Sheridan et al., 2001).

Regardless the well-situated position of community pharmacists to provide healthcare advice on oral and dental problems, limited number of studies have investigated the advisory role played by community pharmacists to address oral health problems. Most of these studies were conducted in UK (Chestnutt et al., 1998, Maunder and Landes, 2005) South Africa (Gilbert, 1998), and India (Priya et al., 2008). In addition, limited oral health training was offered to community pharmacists to address oral healthcare needs of the community and recognized the importance of additional training (Sowter and Raynor, 1997). Therefore, it is important to inquire how often community pharmacists encounter patients complaining about oral health problems including most prevalent oral conditions, and the level of oral health training provided to them.

There is a paucity of evidence about the role of community pharmacists in the oral healthcare-seeking behaviors of Saudi communities and their influence to address the oral health complaints in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. It is useful to compare oral health advice seeking behaviors in community pharmacies in big and small cities in the country. The aim of the study was to determine the frequency of patients seeking advice about oral health complaints in community pharmacies. The study evaluated the prevalence of the most common oral health-related complaints encountered by community pharmacists in addition to the recommendations for dental pain and frequently requested dental products.

2. Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted on the registered community pharmacists in the Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. A list of all the registered community pharmacies in the Province (853 pharmacies) was obtained from Saudi Ministry of Health (MOH). Hospital-based pharmacies were excluded. The sample calculations were made based on total number of pharmacist, 95% confidence interval, anticipated percentage of frequency and design effect which yielded a minimum sample size of 266 pharmacies (Schaeffer et al., 1990). However, the sample size was increased to 332 pharmacists in order to compensate for the non-response and missing information in the questionnaires. Simple random sampling technique was employed using Microsoft Excel 2010. The administrative division of Eastern Province is divided into two categories of cities i.e., category A and B cities. Category A cities (Dammam, Khobar, Al-Ahsa, Jubail, etc.) have larger population and better access to healthcare services, and improved environmental conditions compared to category B cities (Ras Tanura, Khafji, Abqaiq, etc.) (Saudi Regions Law, 1992). The participants were approached in person in both category A and B cities and consents were obtained from those who participated in the survey.

The questionnaire was created based on previous studies (Chestnutt et al., 1998, Maunder and Landes, 2005, Priya et al., 2008) Initial draft of questionnaire was developed and discussed among the researchers of the study and faculty members experienced in dental public health research, and necessary changes were made to improve the instrument. A pilot study was conducted to check the methodology of the study, and to improve the clarity and understanding of questionnaire by the respondents. About 20 pharmacists were included in the pilot study. They were not included in the total participants of the study (Radhakrishna, 2007).

The questionnaire consisted of 25 close-ended questions divided into three broad sections. The first section dealt with the demographic information which included age, nationality, qualification, place of graduation, year of graduation, and number of years working in Saudi Arabia. The second section inquired about the frequency of oral and general health advice, gender and age group of clients seeking oral health advice and common oral conditions encountered. The second section also investigated what usually the pharmacists recommend for oral pain, the pharmacist's confidence in providing oral health advice, the most important factor influencing the pharmacists' advice, attending seminars related to oral healthcare and barriers to providing oral health advices. The third section was about the knowledge of the pharmacists regarding nearest dental clinics and whether there is any arrangement between pharmacy and dental clinic in cases of emergencies. Self-administered structured questionnaire was distributed to the randomly selected community pharmacists across the Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia.

The Scientific Research Unit, University of Dammam, College of Dentistry, provided ethical approval for the study. The privacy, confidentiality and ethical protocols were followed during the collection and analysis of data, and reporting of research findings. The administrative division of Eastern province is divided into two categories of cities i.e., category A and B cities. Category A cities (Dammam, Khobar, Al-Ahsa, Jubail, etc.) have larger population and better access to healthcare, and improved environmental conditions compared to category B cities (Ras Tanura, Khafji, Abqaiq, etc.) (Saudi Regions Law, 1992). The participants were approached in person in both category A and B cities and consents were obtained from those who participated in the survey.

The collected data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Version 22.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) to perform statistical analyses. Pearson's chi-square test was used to compare different variables of the study such as general and oral health advices by pharmacist, gender of clients, oral conditions encountered, recommendations for pain, dental products requested by the clients between category A and B cities. P-value of ≤0.05 was used for testing statistical significance.

3. Results

Of the 332 pharmacists, 279 agreed to participate in the study, yielding a response rate of 84%. The mean age of the pharmacists was 28.0 ± SD 2.0 years and 58.8% were between 26 and 28 years of age. The mean year of working in Saudi Arabia was 3 ± SD 1 year. All participants were non Saudis. Two hundred and seventy eight pharmacists (99.6%) had bachelor degrees, while only one pharmacist had a master degree. About 151 (54.2%) of the pharmacists provided ≥30 general health advices daily and 81 (29%) gave ≥30 dental health advices per day. More male (62%) than female (38%) clients frequently sought dental advices from the pharmacists (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data of the participants.

| Demographic data | (N/%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 26–28 years | 164 | (58.8%) |

| 29–31 years | 88 | (31.5%) |

| 32–34 years | 22 | (7.9%) |

| >35 years | 5 | (1.9%) |

| Nationality | ||

| Saudis | 0 | (0%) |

| Non-Saudis | 279 | (100%) |

| Educational qualification | ||

| Bachelor | 278 | (99.6%) |

| Master and above | 1 | (0.4%) |

| Years of working in Saudi Arabia | ||

| 1–3 years | 134 | (48.1%) |

| 4–6 years | 132 | (47.3%) |

| 7–9 years | 11 | (4%) |

| ≥10 years | 2 | (0.8%) |

Oral ulcer (64.2%), dental pain (59.5%) and bleeding gums (54.5%) were the three most common oral conditions encountered by the pharmacists. About three quarters (77.4%) of pharmacists referred clients to dentists and approximately 28% prescribed analgesics and gave oral hygiene advices. Tooth whitening (86%) topped the list of the most common requests for dental products followed by toothpaste (49.8%) and toothbrush (43.7%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Common oral conditions, recommendations for oral/dental pain and requests for dental products.

| Variables | (N/%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Oral conditions | ||

| Oral ulcer | 179 | (64.2%) |

| Dental pain | 166 | (59.5%) |

| Gum bleeding | 152 | (54.5%) |

| Abscess | 105 | (37.6%) |

| Bad breath | 77 | (27.6%) |

| Denture | 28 | (10%) |

| Tongue problems | 20 | (7.2%) |

| Pharmacists recommendations for oral pain | ||

| Refer to dentist | 216 | (77.4%) |

| Prescribing analgesics | 78 | (28%) |

| Oral hygiene advices | 77 | (27.6%) |

| Refer to physician | 8 | (2.9%) |

| Refer to ER | 4 | (1.4%) |

| Frequently requested dental products | ||

| Tooth whitening | 240 | (86%) |

| Toothpaste | 139 | (49.8) |

| Toothbrush | 122 | (43.7%) |

| Mouthwash | 99 | (35.5%) |

| Dental floss | 30 | (10.8%) |

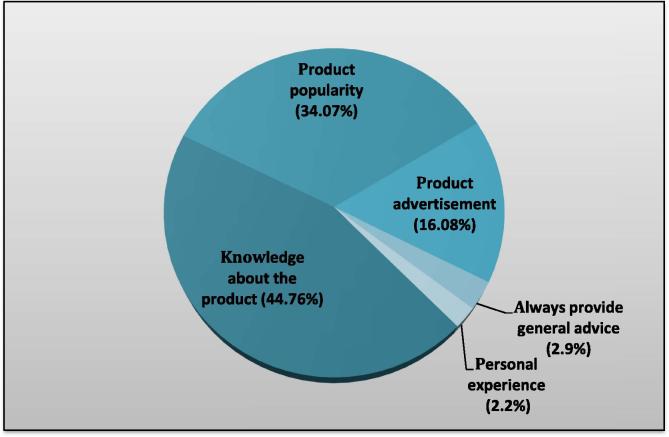

One hundred and twenty five (44.8%) pharmacists gave advice based on products' knowledge, whereas 50.2% recommended products because of their advertisements and popularity (Fig. 1). Seventy four (26.5%) pharmacists said they were always confident, one hundred and ninety one (68.5%) were somewhat confident, and fourteen (5%) were not confident at all in providing oral health advices to the clients. When the participants were asked about having formal oral health training in their undergraduate pharmacy programs, 35.8% (n = 100) said that they had formal training. Only twenty three (8.2%) reported that they attended continuing courses or seminars.

Figure 1.

Factors influencing pharmacists' advices on oral health products.

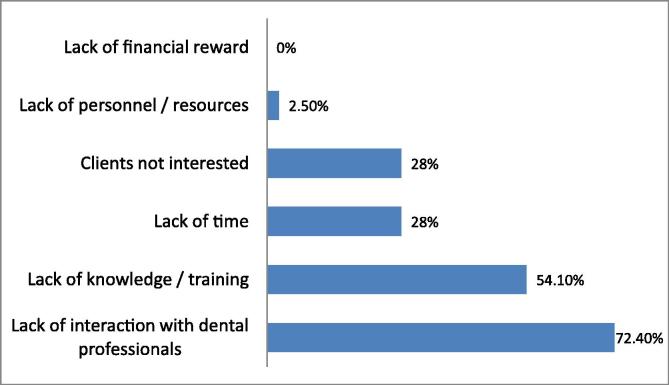

Two hundred and sixty one (93.5%) pharmacists thought that they have an important role in oral health education, and 274 (98.2%) were enthusiastic to provide oral health information in the community. About 72% believed lack of regular meetings with dental professionals as the most important barrier. Lack of oral health knowledge and training (54.1%) was perceived as the second most important barrier (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Barriers to provide oral health services to clients.

More than half of the pharmacists (n = 223) referred patients requiring dental care to the nearest dental clinic. The majority (n = 211) knew the location of nearest clinic but only few (n = 35) had met with dentist/staff. There were no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of oral health conditions encountered by the pharmacists except for tongue problems (p-value 0.003) and denture problems (p-value 0.011) (Table 3). The 90% of the pharmacists in category A cities were asked for tooth whitening product advices in comparison with 66.7% of pharmacist in category B cities (p-value <0.001). Similarly, more pharmacists in category A cities were approached for advices regarding toothbrush (p-value <0.001) and mouthwash (p-value 0.046) than those in category B cities.

Table 3.

Comparison between pharmacists located in category A vs. B cities.

| Variables | Pharmacists in category A cities (N = 231) | Pharmacists in category B cities (N = 48) | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N/%) | (N/%) | ||||||

| General health advices given by the pharmacist per day | <0.001* | ||||||

| Total | |||||||

| ≥30 advices per day | 128 | (45.9%) | 95 | (41.1%) | 33 | (68.8%) | |

| ≤29 advices per day | 151 | (54.2%) | 136 | (58.9%) | 15 | (31.3%) | |

| Oral health advices given by the pharmacist per day | <0.001* | ||||||

| Total | |||||||

| ≥30 advices per day | 198 | (71%) | 151 | (65.4%) | 47 | (97.9%) | |

| ≤29 advices per day | 81 | (29%) | 80 | (34.6%) | 1 | (2.1%) | |

| Gender of clients seeking for oral health advices | <0.001* | ||||||

| Total | |||||||

| Male | 173 | (62%) | 132 | (57.2%) | 41 | (85.4%) | |

| Female | 106 | (38%) | 99 | (42.8%) | 7 | (14.6%) | |

| Oral conditions encountered by the pharmacists | |||||

| Oral ulcer | 147 | (63.6%) | 32 | (66.7%) | 0.689 |

| Dental pain | 135 | (58.4%) | 31 | (64.6%) | 0.427 |

| Bad breath | 65 | (28.1%) | 12 | (25%) | 0.655 |

| Gum bleeding | 121 | (52.4%) | 31 | (64.6%) | 0.119 |

| Tongue problem | 20 | (8.7%) | 0 | (0.0%) | 0.005* |

| Dental abscess | 88 | (38.1%) | 17 | (35.4%) | 0.727 |

| Denture problems | 28 | (12.1%) | 0 | (0.0%) | 0.011 |

| Recommendations for oral/dental pain | |||||

| Analgesics | 67 | (29%) | 11 | (22.9%) | 0.385 |

| Oral hygiene advices | 62 | (26.8%) | 15 | (31.3%) | 0.538 |

| Referral to ER | 4 | (1.7%) | 0 | (0.0%) | 0.217 |

| Referral to physician | 7 | (3%) | 1 | (2.1%) | 0.710 |

| Referral to dentist | 175 | (75.8%) | 41 | (85.4%) | 0.129 |

| Frequently requested dental products | |||||

| Tooth whitening | 208 | (90%) | 32 | (66.7%) | <0.001* |

| Toothpaste | 121 | (52.4%) | 18 | (49.8%) | 0.059 |

| Mouthwash | 88 | (38.1%) | 11 | (22.9%) | 0.040* |

| Toothbrush | 114 | (49.4%) | 8 | (16.7%) | <0.001* |

| Dental floss | 28 | (12.1%) | 2 | (4.2%) | 0.074 |

Statistical significance.

4. Discussion

Pharmacists were actively involved in providing oral health advices, and were willing to participate in oral health activities. The current study has shown that only one quarter of the participants were always confident in providing oral health care advice. The possible reason is that nearly majority of the participants had no formal training courses in oral health in their undergraduate pharmacy programs. In addition, vast majority of them never attended continuing educational courses, seminars or workshops in oral health. The Ministry of Health, KSA should consider providing continuous oral health seminars and workshops to ensure optimal oral health education and training for the pharmacists.

As expected, the pharmacists provided more general health advices compared with oral health advices. These results agree with the findings of a British study (Maunder and Landes, 2005). Similar to the findings of present study, other studies (Maunder and Landes, 2005, Amien et al., 2013, Bawazir, 2014) demonstrated that substantial number of pharmacists was approached for providing symptomatic relief for dental pain and oral ulcer. In addition, the clients frequently sought community pharmacists' advices (86%) for tooth whitening products. Only 10.8% of the clients sought advices for dental floss. This may reflect increasing interest in dental esthetics in KSA. On the contrary, Priya et al. observed no customer seeking advice for tooth whitening product in India (Priya et al., 2008).

Similar to the findings reported by Maunder and Landes (2005), majority of pharmacists (77.4%) in our study referred clients complaining of oral/dental pain to dentists. This high percentage of referral to dentists shows a good trend among the pharmacists that can reduce the possibility for misdiagnosis of oral problems and provision of appropriate dental treatment. Maunder and Landes (2005) also showed that one quarter of pharmacists (23.5%) referred clients to physicians and nearly all of them prescribed analgesics in case of oral pain. On the contrary, the present study found only 2.9% of pharmacists referring clients to physicians and 28% prescribed analgesics. This demonstrates increased awareness among pharmacists about the referral of their clients.

The most common barrier to providing oral health services included lack of interaction between pharmacists and dental professionals. This calls for establishing better professional relationships between dentists and pharmacists. However, the pharmacists also recognized lack of oral health knowledge and training a significant barrier. It is imperative that continuing education opportunities should be provided to practicing pharmacists to better benefit the patients seeking oral health advice.

In contrast to the results acquired by Maunder and Landes (2005) which showed more than half of pharmacist recommended a dental product based on their personal experience; our study found only 2.2% of respondents used personal experience in prescribing a dental product. However, it was encouraging to see about half of respondents recommending dental product based on its knowledge and only few of them made their decision on the product advertisement. It is important to take into account that although the majority of the participating pharmacists recommended their clients to see a dentist in the nearest clinic, a few of them actually met any member of the dental clinic.

The study compared oral health advice seeking behaviors in community pharmacies in the country. More male clients visited pharmacies in comparison with females. This can be attributed to the cultural norms of the Saudi community as men meet the needs of the family, in addition to the transportation limitations concerning females. This trend was more pronounced in category B compared with category A cities. However, more female clients visited community pharmacies in category A compared with category B areas and the difference was statistically significant. There was predominance toward dental whitening products, toothbrushes and mouthwashes in category A cities compared with category B cities which shows greater awareness about dental esthetics and oral hygiene products in major than in smaller cities. This also draws our attention to develop more oral health education programs in small cities and remote areas.

The study included a large random sample of pharmacists from all over the province in comparison with other studies which involved smaller sample of pharmacists collected from a single city (Maunder and Landes, 2005, Priya et al., 2008, Amien et al., 2013). This provided more representative sample and ensured better generalizability of our findings. Nevertheless, our results may not be generalized to the pharmacists working in the hospitals in the province because they were excluded from the study or to other regions of the country. The questionnaires were distributed and collected by dental students and this might raise the possibility for obsequiousness bias and subsequently affect the validity of the study to certain extent (Amien et al., 2013). The response rate was satisfactory. The reason for non-response included lack of time, having no interest in the study, resistance or hesitation due to breach of their confidentiality, and obtaining no prior permission from the administration of the pharmacies.

The results of the study call for revisiting undergraduate pharmacy curricula and establishing more collaboration with dental institutes. Continuing education courses and programs should be tailored according to the needs of pharmacists to maximize their potential of promoting oral health in the community. In addition, communication and interaction between pharmacists and dentists should be established including emergency referral protocols. These measures would increase pharmacists' knowledge and experience in oral health, and would effectively serve the clients.

5. Conclusions

Community pharmacists are approached frequently for oral health advices in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. The clients frequently seek advice about most common oral conditions such as oral ulcer, dental pain and bleeding gums. The study participants refer majority of their clients complaining of oral pain to dentists. The tooth whitening products were most commonly requested in the community pharmacies. Lack of oral health knowledge and lack of interaction with dental professional were main barriers to providing oral health services. The patients living in large cities consult community pharmacist more frequently regarding tooth whitening products, tooth brush and mouth wash compared with those in small cities of the province. The pharmacists realize their essential role in managing and preventing oral health-related problems. However, majority of them do have proper oral health training in their undergraduate pharmacy programs and they are not provided with continuing education courses in oral health. Almost all community pharmacists were willing to provide oral health information in the community.

Ethical statement

The study proposal was approved by the Scientific Research Unit University of Dammam, College of Dentistry.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest. The project was not funded by any organization.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Contributor Information

Hamad Al-Saleh, Email: drhamadalsaleh@hotmail.com.

Thamir Al-Houtan, Email: thmr91@hotmail.com.

Khalid Al-Odaill, Email: kald_2001@hotmail.com.

Basel Al-Mutairi, Email: basel.almutairi@hotmail.com.

Mohammed Al-Muaybid, Email: almuaybidmh@gmail.com.

Tameem Al-Falah, Email: Tameem2007@hotmail.com.

Muhammad Ashraf Nazir, Email: manazir@uod.edu.sa.

References

- Abou-Auda H.S. An economic assessment of the extent of medication use and wastage among families in Saudi Arabia and Arabian Gulf countries. Clin. Ther. 2003;25:1276–1292. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amien F., Myburgh N.G., Butler N. Location of community pharmacies and prevalence of oral conditions in the Western Cape Province. Health SA Gesondheid. 2013;18:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S. Community pharmacy and public health in Great Britain, 1936 to 2006. How a phoenix rose from the ashes. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2007;61:844–848. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.055442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bawazir O.A. Knowledge and attitudes of pharmacists regarding oral healthcare and oral hygiene products in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J. Int. Oral Health. 2014;6:1–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chestnutt I.G., Taylor M.M., Mallinson E.J. The provision of dental and oral health advice by community pharmacists. Br. Dent. J. 1998;184:532–534. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert L. The role of the community pharmacist as an oral health adviser – an exploratory study of community pharmacists in Johannesburg, South Africa. SADJ. 1998;53:439–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson L.M., McCann M.F., Gibson J., Binnie V.I., Stephen K.W. The role of primary healthcare professionals in oral cancer prevention and detection. Br. Dent. J. 2003;195:277–281. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4810481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann R.S., Marcenes W., Gillam D.G. Is there a role for community pharmacists in promoting oral health? Br. Dent. J. 2015;218:E10. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder P.E., Landes D.P. An evaluation of the role played by community pharmacies in oral healthcare situated in a primary care trust in the north of England. Br. Dent. J. 2005;199:219–223. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priya S., Madan Kumar P.D., Ramachandran S. Knowledge and attitudes of pharmacists regarding oral health care and oral hygiene products in Chennai city. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2008;19:104–108. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.40462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishna R.B. Tips for developing and testing questionnaires/instruments. J. Extension. 2007;28:2. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer R.L., Mendenhall W., Ott L. fourth ed. Duxbury Press; Belmont, California: 1990. Elementary Survey Sampling. [Google Scholar]

- Sello D.A., Serfontein H.P., Lubbe M.S., Dambisya Y.M. Factors influencing access to pharmaceutical services in underserviced areas of the West Rand District, Gauteng Province, South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid. 2012;17:609. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan J., Aggleton M., Carson T. Dental health and access to dental treatment: a comparison of drug users and non-drug users attending community pharmacies. Br. Dent. J. 2001;191:453–457. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowter F.R., Raynor D.K. The management of oral health problems in community pharmacies. Pharm. J. 1997;259:308–310. [Google Scholar]

- Steel B.J., Wharton C. Pharmacy counter assistants and oral health promotion: an exploratory study. Br. Dent. J. 2011;211:E19. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]