Abstract

Kaposi Sarcoma (KS) is an intermediate neoplasm affecting the endothelial cells of mucous membranes and skin. It arises most commonly among HIV-infected individuals. We present an intra-oral KS in an 80-year-old Saudi male patient, who is HIV-seronegative, non-immunosuppressed, and with no history of organ transplantation. The patient was treated with fractionated radiation therapy, and had no recurrence in the 48 months of follow-up. The clinical disease, histologic features, and treatment modality used, as well as the relative literature are presented in this paper.

Keywords: Kaposi sarcoma, HIV-seronegative, Non-immunosuppressed, Pyogenic granuloma

1. Introduction

In the 19th century, the dermatologist Moritz Kaposi was the first to describe Kaposi Sarcoma (KS). KS was originally described as plaques affecting the lower limbs of elderly males with Jewish descents (Kaposi, 1872). According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors update in 2002, KS has been moved to intermediate neoplasms (rarely metastasizing) (Fletcher et al., 2002).

Kaposi Sarcoma has been defined as “a multi-centric mucocutaneous neoplasm of endothelial origin” which is present in four clinical forms: classic, iatrogenic, endemic, and epidemic (Fatahzadeh et al., 2013). Classic KS is rare and mild with benign behavior. It has propensity for elderly males with Jewish and Mediterranean origins (Régnier-Rosencher et al., 2013, Ruocco et al., 2013). It is mainly cutaneous, but it can involve lymphatic and visceral organs in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts (Radu and Pantanowitz, 2013). In addition, association was found between classic KS and diabetes (Anderson et al., 2008).

Iatrogenic KS develops in immunosuppressed individuals, who receive immunosuppressive medications for autoimmune disorders, inflammatory conditions or organ transplantation (Lee et al., 2012). Patient’s ethnicity, type of the transplanted organ, and the class of immunosuppressive drugs all affect the probability of iatrogenic KS development (Marcelin et al., 2007). Renal transplants are the most common in iatrogenic KS (Radu and Pantanowitz, 2013). In Saudi Arabia, it was found that the most common neoplasm arising in renal transplant patients was Kaposi Sarcoma, with reported incidence of around 5% (Al-Sulaiman and Al-Khader, 1994, Wajeh et al., 1988). This incidence is significantly greater than what is reported in the United States (Mbulaiteye and Engels, 2006).

The development of KS in organ transplant recipients could be attributed to the transmission of Human Herpes Virus-8 (HHV-8) from the donor or the reactivation of the latent virus in the recipient’s body (Cannon et al., 2007). Withdrawal or decrease in the use of immunosuppressive medications has shown to improve the outcomes of iatrogenic KS and can be curative (Lebbe et al., 2008). Al-Otaibi et al. (2007) observed regression of KS in two patients after withdrawal of Ciclosporin (Cyclosporine) (Al-Otaibi et al., 2007). It is proposed in the literature that the first line of treatment for iatrogenic KS is switching the immunosuppressive medication into Sirolimus, with or without mycophenilate mofetil (Nichols et al., 2011). Ozdemir et al. (2014) reported the absence of recurrence of KS in a renal transplant patient after switching his immunosuppressive drug from Cyclosporin A to Sirolimus (Ozdemir et al., 2014).

Endemic refers to KS occurrence in South Africa (Fatahzadeh, 2012). The incidence of KS in South Africa between 2012 and 2016 was 4.4% (Globocan, 2016). Although KS most commonly affects the elderly (Kaposi, 1872), the endemic or African variant usually affects younger age groups (Dreyer and de Waal, 2009). This variant is characterized by rapid progression, and greater lymphatic involvement (American Cancer Society, 2014).

In 1981, the most common and most aggressive variant was first described among homosexual men. Epidemic KS refers to KS developing in HIV-positive individuals (Dreyer and de Waal, 2009). HIV-related KS in Sub-Saharan Africa occurs in males and females equally (Pantanowitz et al., 2013). After the emergence of human immunodeficiency virus, the incidence of KS increased by 20-fold in Africa and in the United States (American Cancer Society, 2014). Furthermore, KS in HIV-infected individuals is considered as an Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)-defining illness (Martellotta et al., 2009, Radu and Pantanowitz, 2013). After the introduction of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART), the prevalence as well as the severity of AIDS-related KS has decreased (Pantanowitz et al., 2013). Epidemic KS is managed by anti-retroviral therapy, which is curative and prevents recurrence (Feller et al., 2008, Martinez et al., 2006). However, severe symptomatic KS in HIV-positive patients should be treated with anti-retroviral therapy in addition to systemic chemotherapy (World Health Organization, 2014).

The four subtypes of KS share the same clinical presentation, with differences in the severity (Radu and Pantanowitz, 2013). Lesions usually start as patches or plaques, which are asymptomatic, and develop into nodular and exophytic lesions. The lesions can be associated with symptoms such as pain, bleeding, ulceration, secondary infections and pus discharge (Feller et al., 2010, Kalpidis et al., 2006, Patrikidou et al., 2009). In addition, lesions can be single or multiple, varying in number, size and color (Pantanowitz et al., 2013).

KS has been linked to human herpes virus type 8, also known as Kaposi Sarcoma–associated herpes virus (KSHV), which infects endothelial and B cells (Dittmer and Damania, 2013, Wood and Feller, 2008). Saliva is the main mode of transmission (Al-Otaibi et al., 2012, Oh and Weiderpass, 2014). Current evidence signifies the presence and extensive expression of HHV-8 virus in the oral cavity, making it one of the principal sites for viral replication and shedding of such virus (Al-Otaibi et al., 2007, Al-Otaibi et al., 2009). The presence of HHV-8 is essential for development of KS. It is present in all KS cells (Dittmer, 2011). However, its mere presence is insufficient for causing clinical disease (Ruocco et al., 2013). The virus remains latent most of its life span. Co-factors such as decreased immunity and co-infection with HIV-1 play an important role in developing the disease when accompanied with HHV-8 (Dittmer and Damania, 2013, Ruocco et al., 2013).

The most common sites for oral Kaposi Sarcoma (OKS) are hard and soft palates, gingiva, and dorsum of the tongue (Patrikidou et al., 2009). Although oral manifestation of KS can appear in all variants, they develop most frequently with the epidemic type (Feller et al., 2007). In approximately one-fifth of HIV-infected patients, oral KS is the first manifestation of the disease (Feller et al., 2010). Furthermore, oral KS can be the initial indicator of HIV infection (Lager et al., 2003). In a non-immunosuppressed patient under 50 years of age, OKS is considered diagnostic of AIDS (Sengüven et al., 2014).

Various treatment strategies for OKS are proposed in the literature, depending on the type and severity of the disease. Prior to the start of the treatment, it is important to assess for systemic involvements (Vanni et al., 2006). Treatment options include observation, local approaches and systemic therapy. In cases of limited asymptomatic lesions, no intervention is needed (Fatahzadeh et al., 2013). While local approaches are used for focal or extensive regional lesions, systemic therapy is reserved for cases with systemic involvements (Fatahzadeh and Schwartz, 2013, Jakob et al., 2011). Local approaches include excision, sclerotherapy, intralesional injection with vinca alkaloids, photodynamic therapy, radiotherapy and cryotherapy. Systemic approaches include, but are not limited to, HAART, chemotherapy, sirolimus, anti-HHV-8 agents, in addition to other medications (Fatahzadeh et al., 2013). Radiotherapy is reserved for symptomatic and obstructive oropharyngeal KS (Housri et al., 2010).

Although HIV-associated KS is the most common form (Dreyer and de Waal, 2009), cases have been reported in HIV-seronegative patients (Bottler et al., 2007, Braga et al., 2012, Crosetti and Succo, 2013, Kua et al., 2004, Mohanna et al., 2007, Sengüven et al., 2014, Serwin et al., 2006, Sikora et al., 2008, Stern et al., 2016, Wang et al., 2010). Most of these cases were males above 45 years of age (Braga et al., 2012, Crosetti and Succo, 2013, Kua et al., 2004, Mohanna et al., 2007, Serwin et al., 2006, Sikora et al., 2008, Stern et al., 2016). Four patients were of Caucasian origins (Bottler et al., 2007, Crosetti and Succo, 2013, Sengüven et al., 2014, Stern et al., 2016), and three were of Quechua descents (Mohanna et al., 2007, Sikora et al., 2008). Two cases were family related (Mohanna et al., 2007). Although cutaneous lesions were reported (Mohanna et al., 2007, Serwin et al., 2006, Wang et al., 2010), most of the aforementioned cases had oral manifestations without any other mucosal, cutaneous or lymphatic involvements (Braga et al., 2012, Crosetti and Succo, 2013, Kua et al., 2004, Mohanna et al., 2007, Sengüven et al., 2014, Serwin et al., 2006, Sikora et al., 2008, Stern et al., 2016).

Globally speaking, the number of new KS cases within the past 5 years was more than 44 thousands, with a 0.3% incidence (Globocan, 2016). In Saudi Arabia, most of the reported KS cases are from the iatrogenic variant, predominantly following renal transplantation (Al-Wakeel et al., 2000, Bernieh et al., 1999, Kadry et al., 1998, Qunibi et al., 1988, Qunibi et al., 1998). Two articles report KS in Saudi Arabia with no mention of the type (Al Aboud et al., 2003, Mufti, 2012), and one article reports it in HIV-negative patient with autoimmune disease (Noah and Siddiqui, 1985).

We report an intra-oral KS in an 80-year-old Saudi diabetic male patient, who is HIV-seronegative, non-immunosuppressed, and with no history of organ transplantation.

2. Case presentation

An 80-year-old Saudi male presented to the oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics at the College of Dentistry, King Saud University in Saudi Arabia. The patient was complaining from discolorations in his mouth. The patient was known to have Diabetes Mellitus type II, hypertension and history of Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) 8 years ago.

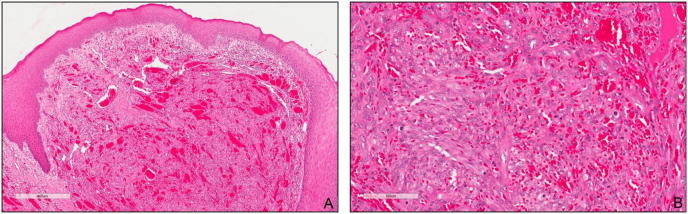

Upon clinical examination, there were multiple painless dark red-purplish lesions at the junction of hard and soft palates, as well as the buccal mucosa and the alveolar ridge (Fig. 1). The lesions were associated in part with teeth #17, 16, and 15. No other lesions were detected in his body, and there were no lymphatic involvements. Differential diagnosis included pyogenic granuloma, bacillary angiomatosis, necrotizing sialometaplasia, granulomatous inflammatory conditions (such as coccidioidomycosis, paracoccidioidomycosis, and aspergillosis) and Kaposi sarcoma. Under local anesthesia, incisional biopsy was taken and sent for histopathologic examination.

Figure. 1.

Erythematous and violaceous soft tissue overgrowth involving alveolar mucosa and palate.

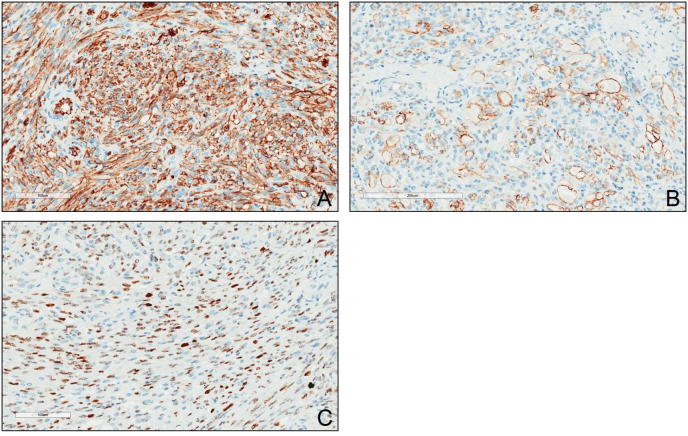

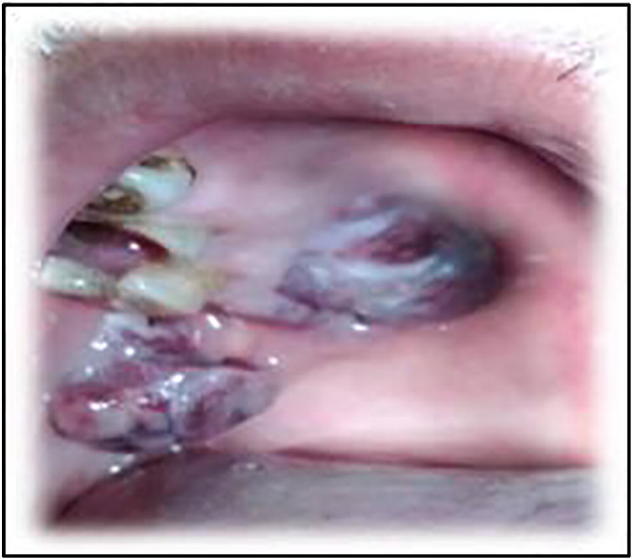

Histopathologic examination showed a lobulated vascular overgrowth enveloped by epithelial collarette mimicking pyogenic granuloma (Fig. 2A). There was evidence of spindle cell proliferation intermixed with numerous congested blood vessels, which was suggestive of KS. There were occasional mitotic figures (Fig. 2B). Immunoperoxidase stain for CD31 showed intense immunoreactivity of the neoplastic spindle cells to CD31 (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, the cells were positive for D2-40 (Fig. 3B), and HHV-8 (Fig. 3C). A serology test for HIV was performed and the result was negative. Histopathologic findings were suggestive of Kaposi Sarcoma.

Figure. 2.

Scanning electron microscopy with Hematoxylin and Eosin staining showing (A) lobulated vascular overgrowth enveloped by epithelial collarette mimicking a pyogenic granuloma (X100) and (B) spindle cell proliferation intermixed with numerous congested blood vessels. There are occasional mitotic figures (X200).

Figure. 3.

Scanning electron microscopy with Immunoperoxidase stain showing (A) intense immunoreactivity of the neoplastic spindle cells to CD31 (X200), (B) cytoplasmic immunoreactivity to D2-40 in the endothelial lining of the vascular channels (X100) and (C) positive HHV-8 nuclear staining of the neoplastic spindle cells and endothelial cells of the vascular channels (X200).

The patient was referred to a specialized oncology center, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center. The case was managed by radiation therapy 30 doses with no extensive surgical interventions. The case was followed periodically for 48 months, and showed no evidence of recurrence. Table 1 summarizes the important points in this case.

Table 1.

Case summary.

| Demographic data | Clinical features | Histopathologic features | Management | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Fractionated radiation therapy | No recurrence for 4 years |

3. Discussion

Kaposi Sarcoma can be manifested as one of its four clinical forms: classic, iatrogenic, endemic, and epidemic (Fatahzadeh et al., 2013). The most common and most aggressive form is the epidemic, HIV-associated KS (Radu and Pantanowitz, 2013). Human Herpes Virus-8 is an essential etiologic factor for the development of KS (Dittmer and Damania, 2013, Wood and Feller, 2008). HHV-8 demonstrates extensive replication and shedding in the oral cavity, particularly the buccal mucosa and the palate (Al-Otaibi et al., 2007, Al-Otaibi et al., 2009).

While the occurrence of KS in non-HIV patients is rare (Dreyer and de Waal, 2009), KS cases in HIV-seronegative individuals have been reported in the literature (Bottler et al., 2007, Braga et al., 2012, Crosetti and Succo, 2013, Kua et al., 2004, Mohanna et al., 2007, Sengüven et al., 2014, Serwin et al., 2006, Sikora et al., 2008, Stern et al., 2016, Wang et al., 2010). Most of these reported cases are males older than 45 years. KS primarily affects elderly male individuals and those with European, Jewish and Mediterranean ancestry (Patrikidou et al., 2009, Wang et al., 2010). Our patient is an 80-year-old Saudi male, who is HIV-seronegative.

Treatment strategies for KS can be local or systemic, depending on the type and severity of the disease (Fatahzadeh et al., 2013). Treatment of the aforementioned cases included observation, symptomatic treatment, excision, local or systemic radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Most of the abovementioned cases were treated by excision alone (Bottler et al., 2007, Crosetti and Succo, 2013, Mohanna et al., 2007, Sengüven et al., 2014, Serwin et al., 2006, Sikora et al., 2008, Wang et al., 2010), while two cases were treated with excision and radiotherapy (Bottler et al., 2007, Mohanna et al., 2007). Three cases had recurrence (Mohanna et al., 2007, Serwin et al., 2006, Wang et al., 2010), and one had multiple new systemic lesions and later passed away (Mohanna et al., 2007).

Due to the high radiosensitivity of KS, it can be treated by radiotherapy (Housri et al., 2010). Caccialanza et al.(2008) report complete recovery in most of classic and HIV-related KS cases treated with radiotherapy at different fractioned doses (Caccialanza et al., 2008). The treatment provided for the reported patient in this study was radiation at 30 fractionated doses, which showed no recurrence in 4 years.

Diabetes has been reported in the literature as a risk factor for classic KS (Anderson et al., 2008). The patient in this report has Diabetes Mellitus type II. Oral manifestations of classic KS are rare (Fatahzadeh et al., 2013); however, they were present in the patient of this study. The most common sites for oral KS are hard and soft palates, gingiva, and dorsum of the tongue (Patrikidou et al., 2009). Cutaneous and mucosal lesions usually start as patches, develop into plaques, and progress into nodules (Radu and Pantanowitz, 2013). In this reported case, nodular dark red-purplish lesions appeared at the junction of hard and soft palates, as well as the buccal mucosa and the alveolar ridge.

Clinically, oral Kaposi Sarcoma can mimic oral purpura, bacillary angiomatosis, and pyogenic granuloma. Final diagnosis should be made upon microscopic examination (Cawson and Odell, 2008, Patrikidou et al., 2009). The differential diagnosis list for this patient included pyogenic granuloma, bacillary angiomatosis, necrotizing sialometaplasia, granulomatous inflammatory conditions (such as coccidioidomycosis, paracoccidioidomycosis, and aspergillosis) and Kaposi sarcoma. Histologically, pyogenic granuloma tends to have polygonal endothelial cells and rounded vessels, in contrast to the slit-like vessels of KS. Furthermore, KS shows hyaline globules and extravasation of red blood cells (Gnepp, 2009). Therefore, careful histopathologic examination with the aid of immunohistochemical markers is of utmost importance to prevent misdiagnosing a malignant condition as a pyogenic granuloma. Thorough examination of our biopsy specimen revealed spindle cell proliferation intermixed with numerous congested blood vessels, which is suggestive of KS. Special staining for the specimen obtained from our patient confirmed the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma.

4. Conclusion

Although Kaposi Sarcoma is of rare occurrence in non-HIV patients, careful medical history, clinical assessment and thorough histologic examination should be conducted. Furthermore, it is noteworthy to consider including KS in the differential diagnosis list due to its resemblance to pyogenic granuloma.

5. Consent

The patient signed a written consent to publish his information in this paper.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Al-Otaibi L.M., Al-Sulaiman M.H., Teo C.G., Porter S.R. Extensive oral shedding of human herpesvirus 8 in a renal allograft recipient. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2009;24:109–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2008.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Otaibi L.M., Moles D.R., Porter S.R., Teo C.G. Human herpesvirus 8 shedding in the mouth and blood of hemodialysis patients. J. Med. Virol. 2012;84:792–797. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Otaibi L.M., Ngui S.L., Scully C.M., Porter S.R., Teo C.G. Salivary human herpesvirus 8 shedding in renal allograft recipients with Kaposi’s sarcoma. J. Med. Virol. 2007;79:1357–1365. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sulaiman M.H., Al-Khader A.A. Kaposi’s sarcoma in renal transplant recipients. Transplant. Sci. 1994;4:46–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Wakeel J., Mitwalli A.H., Tarif N., Malik G.H., Al-Mohaya S., Alam A., El Gamal H., Kechrid M. Living unrelated renal transplant: outcome and issues. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transplant. 2000;11:553–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Aboud K.M., Al Hawsawi K.A., Bhat M.A., Ramesh V., Ali S.M. Skin cancers in Western Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2003;24:1381–1387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society, 2014. Kaposi Sarcoma.

- Anderson L.A., Lauria C., Romano N., Brown E.E., Whitby D., Graubard B.I., Li Y., Messina A., Gaf?? L., Vitale F., Goedert J.J. Risk factors for classical Kaposi sarcoma in a population-based case-control study in sicily. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2008;17:3435–3443. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernieh B., Nezamuddin N., Sirwal I.A., Wafa A., Abbade M.A., Nasser B., Al Razzaz Z. Short-tem post renal trasplant follow-up at Madinah Al Munawarah. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transplant. 1999;10:493–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottler T., Kuttenberger J., Hardt N., Oehen H.-P., Baltensperger M. Non-HIV-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma of the tongue. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007;36:1218–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga D., Bezerra T., de Matos V., Cavalcante F. Uncommon diagnosis of oral Kaposi’s Sarcoma in an Elderly Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Seronegative Adult. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012;60:1174–1176. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caccialanza M., Marca S., Piccinno R., Eulisse G. Radiotherapy of classic and human immunodeficiency virus-related Kaposi’s sarcoma: results in 1482 lesions. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2008;22:297–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon M., Boshoff C., Weiss R.A. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2007. Kaposi Sarcoma Herpesvirus: New Perspectives, Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. [Google Scholar]

- Cawson R., Odell E. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2008. Cawson’s Essentials of Oral Pathology and Oral Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Crosetti E., Succo G. Non-human immunodeficiency virus-related Kaposi’s sarcoma of the oropharynx: a case report and review of the literature. J. Med. Case Rep. 2013;7:293. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmer D.P. Restricted Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS) Herpesvirus Transcription in KS Lesions from Patients on Successful Antiretroviral Therapy. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2011;2 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00138-11. (e00138-11-e00138-11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmer D.P., Damania B. Kaposi sarcoma associated herpesvirus pathogenesis (KSHV) - an update. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2013;3:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer W., de Waal J. Oral medicine case book 21. SADJ. 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatahzadeh M. Kaposi sarcoma: review and medical management update. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2012;113:2–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatahzadeh M., Schwartz R.A. Oral Kaposi’s sarcoma: a review and update. Int. J. Dermatol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatahzadeh M., Schwartz R.A., Edin F. Oral Kaposi’s sarcoma: a review and update. Int. J. Dermatol. 2013;52:666–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller L., Khammissa R.A.G., Gugushe T.S., Chikte U.M.E., Wood N.H., Meyerov R., Lemmer J. HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma in African children. SADJ. 2010;65:20–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller L., Lemmer J., Wood N.H., Jadwat Y., Raubenheimer E.J. HIV-associated oral Kaposi sarcoma and HHV-8: a review. J. Int. Acad. Periodontol. 2007;9:129–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller L., Masipa J., Wood N., Raubenheimer E., Lemmer J. The prognostic significance of facial lymphoedema in HIV-seropositive subjects with Kaposi sarcoma. AIDS Res. Ther. 2008;5:2. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher C., Unni K., Mertens F. IARC Press; Lyon: 2002. World Health Organisation Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. [Google Scholar]

- Globocan, 2016. Population Fact Sheets [WWW Document]. Int. Agency Res. Cancer. globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_population.aspx.

- Gnepp D. second ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009. Diagnostic Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. [Google Scholar]

- Housri N., Yarchoan R., Kaushal A. Radiotherapy for patients with the human immunodeficiency virus: are special precautions necessary? Cancer. 2010 doi: 10.1002/cncr.24878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob L., Metzler G., Chen K.-M., Garbe C. Non-AIDS associated Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinical features and treatment outcome. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e18397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadry Z., Bronsther O., Fung J.J. Kaposi’s sarcoma in liver transplant recipients on FK506. Transplantation. 1998;65:1140. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199804270-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalpidis C.D.R., Lysitsa S.N., Lombardi T., Kolokotronis A.E., Antoniades D.Z., Samson J. Gingival involvement in a case series of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related Kaposi sarcoma. J. Periodontol. 2006;77:523–533. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaposi M. Idiopathisches multiples Pigmentsarkom der Haut. Arch. Dermatol. Syph. 1872;4:265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Kua H.W., Merchant W., Waugh M.A. Oral Kaposi’s sarcoma in a non-HIV homosexual White male. Int. J. STD AIDS. 2004;15:775–777. doi: 10.1258/0956462042395104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lager I., Altini M., Coleman H., Ali H. Oral Kaposi’s sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study from South Africa. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2003;96:701–710. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(03)00370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebbe C., Legendre C., Frances C. Kaposi sarcoma in transplantation. Transplant. Rev. 2008;22:252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.Y., Jo Y.M., Chung W.T., Kim S.H., Kim S.Y., Roh M.S., Lee S.W. Disseminated cutaneous and visceral Kaposi sarcoma in a woman with rheumatoid arthritis receiving leflunomide. Rheumatol. Int. 2012;32:1065–1068. doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-1354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcelin A.G., Calvez V., Dussaix E. KSHV after an organ transplant: should we screen? Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007;312:245–262. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-34344-8_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martellotta F., Berretta M., Vaccher E., Schioppa O., Zanet E., Tirelli U. AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma: state of the art and therapeutic strategies. Curr. HIV Res. 2009;7:634–638. doi: 10.2174/157016209789973619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez V., Caumes E., Gambotti L., Ittah H., Morini J.-P., Deleuze J., Gorin I., Katlama C., Bricaire F., Dupin N. Remission from Kaposi’s sarcoma on HAART is associated with suppression of HIV replication and is independent of protease inhibitor therapy. Br. J. Cancer. 2006;94:1000–1006. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbulaiteye S.M., Engels E.A. Kaposi’s sarcoma risk among transplant recipients in the United States (1993–2003) Int. J. Cancer. 2006;119:2685–2691. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanna S., Bravo F., Ferrufino J.C., Sanchez J., Gotuzzo E. Classic Kaposi’s sarcoma presenting in the oral cavity of two HIV-negative quechua patients. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2007;12:365–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mufti S.T. Pattern of skin cancer among Saudi Patients who attended King AbdulAziz University Hospital between Jan 2000 and Dec 2010. J. Saudi Soc. Dermatol. Dermatol. Surg. 2012;16:13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols L.A., Adang L.A., Kedes D.H. Rapamycin blocks production of KSHV/HHV8: insights into the anti-tumor activity of an immunosuppressant drug. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e14535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noah M.S., Siddiqui M.A. Autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura in the course of Kaposi’s sarcoma–report of a case. Am. J. Hematol. 1985;18:319–323. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830180315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J.K., Weiderpass E. Infection and cancer: global distribution and burden of diseases. Ann. Glob. Heal. 2014;80:384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdemir K., Dincel N., Yılmaz E., Yaman B., Gozuoglu G. Treatment of oral Kaposi sarcoma by sirolimus in renal transplanted children: case report and literature review. Glob. Adv. Res. J. Med. Med. Sci. 2014;3:152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Pantanowitz L., Khammissa R.A.G., Lemmer J., Feller L. Oral HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2013;42:201–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2012.01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrikidou A., Vahtsevanos K., Charalambidou M., Valeri R., Xirou P.K.A. Non-AIDS Kaposi’s sarcoma in the head and neck area. Head Neck. 2009;31:260–268. doi: 10.1002/hed.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qunibi W., Akhtar M., Kirtikant S., Ginn E., Al-furayh O., Devol E. Kaposi’s sarcoma: the most common tumor after renal transplantation in Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Med. 1988;84:225–232. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90418-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qunibi W., Al-Furayh O., Almeshari K., Lin S.F., Sun R., Heston L., Ross D., Rigsby M., Miller G. Serologic association of human herpesvirus eight with posttransplant Kaposi’s sarcoma in Saudi Arabia. Transplantation. 1998;65:583–585. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199802270-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radu O., Pantanowitz L. Kaposi Sarcoma. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2013;137:289–294. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0101-RS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Régnier-Rosencher E., Guillot B., Dupin N. Treatments for classic Kaposi sarcoma: a systematic review of the literature. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2013;68:313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruocco E., Ruocco V., Tornesello M.L., Gambardella A., Wolf R., Buonaguro F.M. Kaposi’s sarcoma: etiology and pathogenesis, inducing factors, causal associations, and treatments: facts and controversies. Clin. Dermatol. 2013;31:413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengüven B., Tükel C., Yücel Ö.Ö., Günhan Ö. Primary multinodular oral Kaposi’s sarcoma - HIV seronegative young patient: report of a case. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Med. Pathol. 2014;27:442–445. [Google Scholar]

- Serwin A.B., Mysliwiec H., Wilder N., Schwartz R.A., Chodynicka B. Three cases of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma with different subtypes of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Int. J. Dermatol. 2006;45:843–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikora A.G., Shnayder Y., Yee H., DeLacure M.D. Oropharyngeal kaposi sarcoma in related persons negative for human immunodeficiency virus. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2008;117:172–176. doi: 10.1177/000348940811700303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern J.K., Stern I., De Rossi S.S., Zemse S.M., Abdelsayed R. Kaposi sarcoma presenting as “diffuse gingival enlargement”: report of three cases. HIV AIDS Rev. 2016:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Vanni T., Sprinz E., Machado M.W., de Santana R.C., Fonseca B.A.L., Schwartsmann G. Systemic treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma: current status and perspectives. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wajeh Q., Mohamed A., Sheth K., Ginn H.E., Al-furayh O., Devol E.B., Saadi T. Kaposi’s sarcoma: the most common tumor after renal transplantation in Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Med. 1988;84:225–232. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90418-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Wang X., Liang D., Lan K., Guo W., Ren G. Classic Kaposi’s sarcoma in Han Chinese and useful tools for differential diagnosis. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:654–656. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood N.H., Feller L. The malignant potential of HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2008;8:14. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-8-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2014. Guidelines on the Treatment of Skin and Oral HIV-Associated Conditions in Children and Adults. [PubMed]