Abstract

It has been claimed that in order to decrease the gap between what we know and what we do, research findings must be translated from knowledge to action. Such practices better enable dentists to make evidence-based decisions instead of personal ideas and judgments. To this end, this literature review aims to revisit the concepts of knowledge translation and evidence-based dentistry (EBD) and depict their role and influence within dental education. It addresses some possible strategies to facilitate knowledge translation (KT), encourage dental students to use EBD principles, and to encourage dental educators to create an environment in which students become self-directed learners. It concludes with a call to develop up-to-date and efficient online platforms that could grant dentists better access to EBD sources in order to more efficiently translate research evidence into the clinic.

Keywords: Dental education, Evidence-based dentistry, Patient care, Translational medical research

1. Background

Knowledge translation (KT) concerns the application of the best available evidence to benefit health and well-being. This is a substantive process that involves a range of stakeholders who interact within the healthcare system (Salbach, 2010, MacDermid and Graham, 2009, Hassan, 2013). Evidence-based dentistry (EBD), on the other hand, is the process of combining the best available scientific evidence and the clinical expertise of dentists with patient needs and preferences in order to serve as the foundation for clinical care (Niederman et al., 2011, Ismail et al., 2004). It has been claimed that even busy dentists can easily implement EBD with the use of technology and electronic EBD resources (Gillette, 2008, Seals and Jones, 2003). EBD is particularly important in treatment planning, which is the process in which critical decisions toward patient care take place.

Evidence-based treatment planning in dentistry is meant to help clinicians provide the most contemporary treatment justified by the stronger reasoning following from a thorough review of alternative treatments, diagnostic information, patient desires and evidence-based outcome data (Anderson, 2000, Anon., 2009, Bidra, 2014, Seals and Jones, 2003, Kwok et al., 2012, Wood et al., 2004). Unfortunately, implementation of an evidence-based practice (EBP) by dentists is very limited due to its complexity. Therefore, this paper is intended to familiarize dental students and clinicians with KT and EBD concepts in order to promote their adoption on a daily-basis.

2. Knowledge translation

2.1. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research

In Canada, the main federal agency accountable for supporting financially health research is the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Part of its mandates is to excel in the establishment of novel health information and to translate that knowledge from the research setting into practice (Tetroe, 2007).

The first reason policy makers sought the need to include the process of KT to CIHR principles is that when innovative knowledge is generated, it is not necessarily likely to become widely adopted or make an impact on the health sector (Tetroe, 2007). In fact, only 14% of new research enters day-to-day healthcare practice (Westfall et al., 2007) and the implementation process may take between 17 (Balas et al., 2000) and 20 years (Ho et al., 2003). Another reason to pay attention to KT is that recently the emphasis on research governance and accountability from the government and the public has grown (Tetroe, 2007). According to Statistics Canada (Graham et al., 2007), roughly $700 million was spent on high-quality health research between 1988 and 2005 by CIHR. For example, despite billions of dollars spent on health research in North America, its healthcare systems often fail to implement cost-effective services (Grimshaw et al., 2012). In fact, for every $1 spent on new discoveries, about $0.01 is spent on disseminating information (Farmer et al., 2008). Moreover, the government and the public are eager to see the expected positive outcomes from taxpayers’ money used in health research within real-world applications.

2.2. Knowledge translation definition

The concepts of KT, knowledge exchange, research utilization, implementation, diffusion, and dissemination are frequently confused and misunderstood (Graham et al., 2006). KT is specifically about turning knowledge into action and encompasses the processes of both knowledge creation and knowledge application (Graham et al., 2006). The most well-known definition of KT was given by CIHR (Tetroe, 2007) in 2000:

“Knowledge translation is the exchange, synthesis and ethically-sound application of knowledge—within a complex system of interactions among researchers and users—to accelerate the capture of the benefits of research for Canadians through improved health, more effective services and products, and a strengthened health care system.”

Nonetheless, while Dr. Ian Graham was vice president of KT for CIHR, he slightly modified the definition in order to better elucidate KT’s essential components (Tetroe, 2007). This version reads as follows:

“Knowledge translation is a dynamic and iterative process that includes the synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically-sound application of knowledge to improve the health of Canadians, provide more effective health services and products and strengthen the healthcare system.”

By promoting the value of “synthesis and the ethically sound application of knowledge” in the definition, it also suggests that particular attention should be given to the knowledge that needs to be translated including the audience to which it is directed, acknowledging all the ways that the knowledge could be applied. Therefore, researchers are highly encouraged by CIHR to translate their findings with a consideration of both their message and its appropriate audience (Grimshaw et al., 2012, Ioannidis, 2006, Anon., 2014).

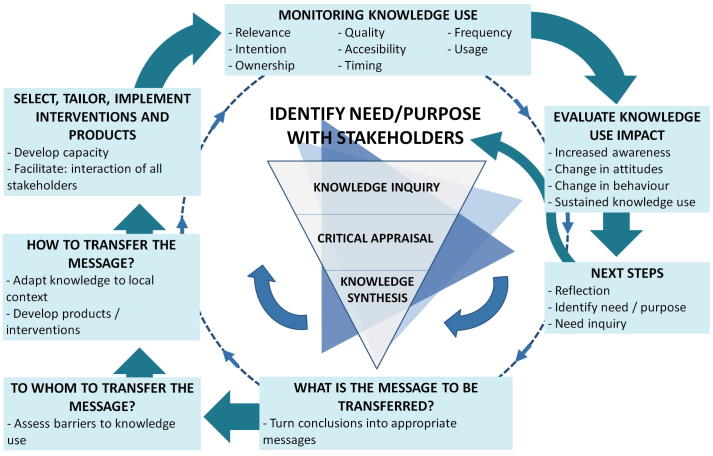

2.3. Knowledge to action

Knowledge to action is an organic process with defined steps as explained in Fig. 1 (Graham et al., 2006). In order to decrease the gap between what we know and what we do, research findings need to be translated from knowledge to action, but in a judicious manner (Graham and Tetroe, 2007). At the center, the “knowledge creation funnel” suggests that knowledge first needs to be refined in order to be ready for application. The model stresses the importance of synthesis using quantitative or qualitative methods to contextualize and integrate the findings of a single study within a larger body of literature. In addition, synthesis is essential to develop knowledge tools, to determine best practice and to establish an evidence-based foundation for proper KT. The types of studies included in a synthesis should be reported in order to establish the credibility and generalizability of the evidence foundation from which the knowledge is intended to be transferred (Fig. 1). The ensuring steps in the action cycle are found to be surrounding the “knowledge creation funnel.” These steps are derived from planned action theories (Graham et al., 2007). However, classical implementation theories have been excluded because they are passive and are primarily used to retrospectively understand change (Tetroe, 2007, Graham et al., 2006).

Figure 1.

Knowledge in Action model (adapted from Graham et al., 2006).

2.4. Need for knowledge translation

Some of the reasons for the importance of KT development are as follows:

-

–

About one-third (30–45%) of patients are not treated with interventions of proven effectiveness (Grol, 2001).

-

–

About one-fourth (20–25%) of patients receive unnecessary or risky interventions (Grimshaw et al., 2012, Schuster et al., 2005).

-

–

As many as three-quarters of patients do not receive the proper information for decision-making (Straus et al.).

-

–

As many as half of clinicians do not use the evidence required for decision-making (Schuster et al., 2005, McGlynn et al., 2003).

In general, patients and clinicians fail to benefit optimally from scientific and medical advances (Grimshaw et al., 2012).

2.5. Ways to do knowledge translation

2.5.1. Knowledge creation

There are three main ways of generating knowledge (Grimshaw et al., 2012, Graham et al., 2006, Ioannidis, 2006, Straus et al., xxxx):

-

1.

To derive knowledge from primary studies (e.g. randomized controlled trials).

-

2.

To synthesize primary studies in order to structure secondary knowledge (e.g. systematic reviews).

-

3.

To generate third-generation knowledge which is based on best available evidence distilled from secondary knowledge (e.g. practice guidelines, decision aids).

2.5.2. Knowledge application

There are at least seven ways of applying knowledge (Grimshaw et al., 2012, Graham et al., 2006, Ioannidis, 2006, Straus et al., xxxx):

-

1.

After identifying the problem, to identify, review and select the knowledge.

-

2.

To adapt more general knowledge to a local context.

-

3.

To assess barriers and facilitators to knowledge application.

-

4.

To select, tailor and implement interventions that tackle barriers to knowledge utilization.

-

5.

To monitor knowledge application.

-

6.

To evaluate outcomes of knowledge utilization.

-

7.

To develop mechanisms to maintain knowledge application.

3. Evidence-based medicine and dentistry

3.1. Evidence-based medicine

It was not until 1981 that guidelines for critically appraising the evidence that informs clinical practices first appeared (Anon., 1981), and it was only in 1991 that the term “evidence-based medicine” made its debut within the medical literature (Cook et al., 1992). Over the last two decades, evidence-based medicine (EBM) has not only become an accepted approach within medicine worldwide but also the standard of medical care (Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group, 1992, Rabb-Waytowich, 2009a, Werb and Matear, 2004). EBM has rapidly created a vigorous intellectual community devoted to making clinical practice more scientific and empirically grounded and thereby providing safer, more consistent, and more cost-effective health care (Greenhalgh et al., 2014).

EBM is defined as (Sackett et al., 1996):

“the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients […] integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research […] and compassionate use of individual patients' predicaments, rights, and preferences in making clinical decisions about their care.”

Individual clinical expertise refers to the proficiency and judgment that clinicians obtain through clinical experience and practice. A consideration of the patient’s needs and preferences as well as the use of the current best evidence is also integral component of the practice of EBM.

3.1.1. Evidence-based Medicine objective

The objective of EBM was to strengthen the scientific basis of medicine and to diminish uncertainties during decision-making (Sackett et al., 1996, Rosenberg and Sackett, 1996). Therefore, EBM applies the results of the best research to advance decision-making in order to smoothen the path toward the best treatments possible (Olatunbosun et al., 1998).

3.1.2. Hierarchy of evidence

The hierarchy of evidence in EBM could be explained as a pyramid that shows the best possible medical evidence at the top (Fig. 2). As one climbs the pyramid from bottom to top, the quality of evidence improves. The higher a particular treatment is within the hierarchy, the more likely it is to actually be effective. Filtered information is contained within the top three blocks, whereas unfiltered information is contained within the next three blocks below critically-appraised individual articles.

Figure 2.

Hierarchy of research designs in evidence-based medicine (SR, Systematic reviews; MA, Meta-analysis).

3.2. Evidence-based dentistry

As in medicine, dentistry has also adopted the concept of EBP. The first article to use the term “evidence-based dentistry” was published in 1991 (Richards and Lawrence, 1995).

The American Dental Association has a comprehensive definition for EBD (Younossi and Guyatt, 1999):

“EBD is an approach to oral health care that requires the judicious integration of systematic assessments of clinically relevant scientific evidence, relating to the patient’s oral and medical condition and history, with the dentist’s clinical expertise and the patient’s treatment needs and preferences.”

EBD can also be briefly defined as (Niederman et al., 2011, Ismail et al., 2004):

“the integration of science, clinician experience, and patient values serving as the foundation for clinical care.”

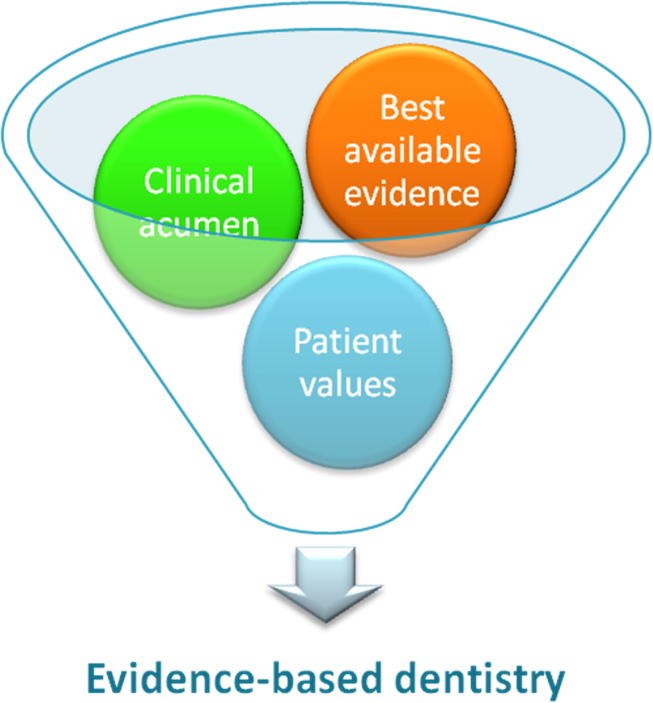

The definition of EBD has three main components (Fig. 3) (Sackett et al., 1996):

-

•

The best current evidence.

-

•

The clinician’s expertise.

-

•

The patient’s values and preferences.

Figure 3.

EBD components.

3.2.1. Evidence-based dentistry significance

EBD is helpful in many ways and is rapidly emerging to become an integral part of patient care, dental education, and dental research. For example, dentists who make evidence-based decisions instead of personal ideas and judgments, experience a significant improvement in their clinical skills and expertise (Bidra, 2014, Rabb-Waytowich, 2009a, Rabb-Waytowich, 2009b, Werb and Matear, 2004, Azarpazhooh et al., 2008). EBD has not only gained great popularity but also is considered a need in the everyday clinical care of dental patients (Werb and Matear, 2004, Azarpazhooh et al., 2008). This type of education facilitates the dentists’ understanding of basic and applied sciences while also increasing their knowledge on how to treat complex cases (Meyer, 2008). Importantly, applying EBD serves to decrease the existing gap between the clinical research and daily dental practice (Sutherland, 2000, Bader et al., 1999, Benjamin and Group, 2009). EBD also creates a large number of new fields for dental research, although these opportunities are in need of extensive evaluation. Hard work on the part of researchers is still required in order to achieve the aims of EBD (Rabb-Waytowich, 2009b).

Although EBD is a well-established concept, recently there has been a new focus on assessing research quality levels within EBD (Marshall et al., 2013). Therefore, dentists would also need to appraise the validity of the available evidence in order to evaluate advantages and disadvantages of potential treatment modalities (Meyer, 2008). Dentists could thus consequently improve the quality and results of treatment and may further increase patient trust in dental care. This last point holds more and more importance as dental patients may present situations addressed with diverse treatment plans that differed between current and former dentists (Anderson, 2000).

3.2.2. The five-step approach in practicing evidence-based dentistry

EBP is about using the current evidence to solve clinical questions (Coulter, 2001). Dentists must follow the following five steps in clinical decision-making (Niederman and Badovinac, 1999, Sutherland, 2001a, Sutherland, 2001b, Bayne and Fitzgerald, 2014):

-

(1)

Recognize a need for information and formulate an answerable question. For clearness, clinical questions are normally framed in terms of the problem (P), intervention or exposure (I), comparison (C), outcome (O) and time (T).

-

(2)

Use electronic databases to find best available evidence, looking particularly for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and double-blind randomized control trials (RCTs).

-

(3)

Critically appraise the evidence for validity, reliability, risk of bias, relevance, usefulness and importance (Brignardello-Petersen et al., 2015a, Brignardello-Petersen et al., 2015b, Brignardello-Petersen et al., 2015c).

-

(4)

Integrate the appraisal within the scope of the clinician’s expertise and the patient’s perceived needs in order to apply these results to clinical practice.

-

(5)

Evaluate the overall results and of those of the EBD process.

This EBD process may be summarized as follows: ask, acquire, appraise, apply, and evaluate. This approach eliminates the more subjective judgments common to more traditional models of care based primarily or only on the dentist’s accumulated knowledge and experience, adherence to accepted standards, and the opinion of experts and colleagues (Anon., 1994).

4. Types of studies

4.1. Primary research

The perspectives and outcome designs of clinical trials are quite varied. In terms of perspectives, clinical trials can be prospective, cross-sectional, or retrospective. In terms of the outcome designs, clinical trials can be Randomized Control Trails (RCTs), cohort studies or case-control studies (Bayne and Fitzgerald, 2014).

4.2. Secondary research

Secondary research uses the existing data and findings of scientific publications. Some of these studies use aggregation techniques (e.g. meta-analyses) in order to allow meaningful combinations of clinical data from trials with similar designs but with fewer rigor. Appraisal studies are attempts to answer clinical questions by assessing the entire evidence base without bias (Bayne and Fitzgerald, 2014).

4.2.1. Systematic review

Systematic reviews are a form of secondary research that attempts to remove the bias frequently found in narrative reviews (Abt and Pihlstrom, 2012). Systematic reviews summarize and synthesize the available evidence related to diagnosis, therapy, prognosis, and harm for clinicians and decision makers. Such reviews represent one of the most powerful tools to translate knowledge into action (Carrasco-Labra et al., 2015a, Glasziou et al., 2010, Afrashtehfar et al., 2016a). Systematic reviews are considered the base and best resource of EBD since they synthesize the best evidence and provide the basis for clinical practice guidelines (Sutherland, 2000, Karimbux, 2015). It is vital to periodically update systematic reviews in order to include new studies and enable prospective and accurate comparison of treatment outcomes.

4.2.1.1. Strengths and weakness of different types of systematic reviews

A majority of Cochrane reviews in dentistry presently conclude with a “lack of sufficient evidence” to recommend one treatment versus another derived from rigorous inclusion criteria and the scarcity of RCTs (Bidra, 2014).

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies (OS), RCTs or combining both study designs (RCTs and OS) are widely accepted in dentistry as well as prosthodontics. Such reviews are better balanced to scrutinize more data in order to answer a given clinical question, in comparison with systematic reviews of only RCTs where data are limited (Afrashtehfar et al., 2017, Bidra, 2014). It is imperative to note that the risk of bias is high in systematic reviews of OS compared with systematic reviews of only RCTs.

4.2.2. Critical appraisal

The critical appraisal of systematic reviews involves assessing the risk of bias, results, and applicability of such studies (Carrasco-Labra et al., 2015a). The credibility of systematic reviews depends on whether or not the authors addressed a sensible clinical question, included an exhaustive literature research section, demonstrated reproducibility of the selection and assessment of the studies, and presented the results in an useful manner (Bayne and Fitzgerald, 2014, Murad et al., 2014). Varying intensities of appraisals to assess the entire evidence base exist such as Cochrane Collaboration, ADA-EBD Library, UTHSCSA CATs and Evidence-Based Dentistry by nature (Afrashtehfar, 2016a, Afrashtehfar, 2016b). Unfortunately, only a fraction of the available evidence is often presented in a usable form, and few clinicians are aware that such usable shared decision aids exist (Greenhalgh et al., 2014, Murad et al., 2014, Afrashtehfar et al., 2016b).

4.2.3. Optimized online knowledge transfer systems

It has been proposed that rapid access to evidence-based knowledge may help dental clinicians, mentors, researchers, and students to implement effectively evidence-based practice (Afrashtehfar et al., 2016b).

At this moment, there are a few free online sites such as http://ebhnow.com/ which intend to translate the evidence to the clinic in a more rapid and efficient way. This site contains Crown or Fill (CoF) at http://crownorfill.com/ and provides evidence-based literature for restoring posterior single-unit teeth by answering to two host-dependent risk factors: (1) is there a root canal treatment? and, (2) how many remaining dentin walls are there?

Implant or Bridge (IoB) at http://ebhnow.com/apps/0020/index.php provides instant access to the literature on the side effects of drugs on bone, osseointegration, and dental implants. The last site, Drugs and Bones (D&B) can be found at http://ebhnow.com/apps/0040/index.php and provides the evidence-based literature on treatment outcomes for the restoration of single missing teeth as a function of preexisting conditions (abutments vitality, site of the missing tooth, need or not for bone grafting for the edentulous area).

5. Barriers to evidence-based decisions

It is believed that less than ten percent of dental care is based on validated dental research (Kao, 2006a, Kao, 2006b, Kao, 2011). Major barriers for evidence-based decisions for dentists are that the search for high-quality evidence can be a complicated, overwhelming and time-consuming task (Shah and Chung, 2009, Clarkson and Bonetti, 2009, Afrashtehfar et al., 2016b). One of the reasons for the complexity of the search is that of the significant increase in the number of published articles and the vast amount of resources available to clinicians since the advent of the internet (Sears et al., 2007, Marinho et al., 2001). For example, the publication rate of articles in the biomedical research field is approximately 5000 per day (Clarkson and Bonetti, 2009). Another reason for search complication is the need to critically assess the quality of any study, and to analyze the results of single studies unless they are already integrated within a larger body of literature (Clarkson and Bonetti, 2009, Abt et al., 2012). Clinical decisions should not be based on the results of individual studies but the totality of the best evidence (Murad et al., 2014). Also, when multiple studies suggest contradictory results or interventions, this complicates the search even more (Shah and Chung, 2009, Spallek et al., 2010). No matter how scrupulous the dentist may be, the existence of publication bias increases the complications of the search process (Clarkson and Bonetti, 2009, Johnson and Dickersin, 2007). Other barriers include the lack of clinical practice guidelines (Kao, 2006a, Kao, 2006b, Kao, 2011), as the few that are available seem to have a limited effect on routine procedures (McGlone et al., 2001) in spite of representing highly processed evidence with associated recommendations to inform clinical practice and improve patient care (Carrasco-Labra et al., 2015b).

Another common barrier for dentists is the high degree of complexity in shifting from the present practice model to one of EBP. Dentists often resist such a change and criticize EBD because they find it infeasible and lack trust in evidence or research. Moreover, dentists do not always have open access to the necessary sources for research, and some dentists may prefer to sacrifice their own financial incentives (Kao, 2006a, Kao, 2006b, Kao, 2011, Spallek et al., 2010, Chiappelli et al., 2003, Pitts, 2004a, Pitts, 2004b). Furthermore, when dentists are provided with solid information, they can take up to 15 years to considerably modify their practice (Pitts, 2004b, Pitts, 2004c, Davis et al., 1999). Lack of training, support, and specific knowledge about the methodology in dental educators is another common and important barrier (Werb and Matear, 2004), since dental education should provide graduates with tools to constantly adapt to evolving advances in dental research (Azarpazhooh et al., 2008, Pitts, 2004c). Patients may also provide impediments to the spread of EBD based on personal desires or limited insurance benefits (Kao, 2006a, Kao, 2006b, Kao, 2011).

Some of the methods for effectively promoting behavior change in dentists are to train them on the five step process (Marinho et al., 2001). Many of the above-mentioned barriers and complications can be addressed using systematic reviews, since this type of study adheres to reproducible methods and recommended guidelines for quality grading of every study that is part of the body of evidence surrounding an issue (Karimbux, 2015, Margaliot and Chung, 2007). Other strategies include critical summaries of systematic reviews, along with evidence-based treatment recommendations, since these are highly condensed, easily accessible tools dentists can use to stay up-to-date with research findings (Abt et al., 2012).

6. Evidence-based dentistry education

Nowadays, dental students are expected to be not only lifelong learners but also proficient at critical thinking and EBP (Zander et al., 2013). Indeed, the Standard 5–2 of the Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) (CODA, 2015) states that “Patient care must be evidence-based, integrating the best research evidence and patient values.”

Dental educators have an important role to play in teaching EBD principles, providing communication skills to aid decision-making, promoting lifelong education, and closing the gap between academics and dental students/clinicians for implementing change, both in the classroom and on the clinic floor (Azarpazhooh et al., 2008, Pitts, 2004c, Sarrett, 2004, Forrest, 2006). Teaching dental students EBD increases the proportion of treatments that will be evidence-based (Sakaguchi, 2010, Faggion and Tu, 2007), and it provides dentists with the skills to stay up to date long after graduation (Karimbux, 2013).

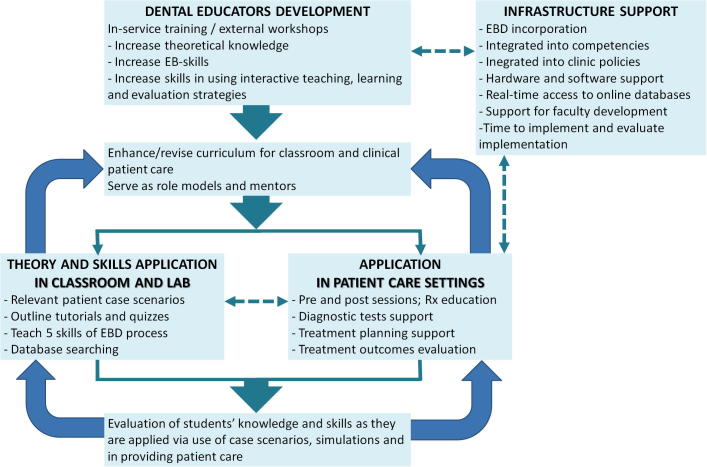

It is important that dental educators create an environment in which students become self-directed learners applying EBD skills (Forrest, 2006). It has been proposed in order for an EBD approach to become the norm for practice it must be integrated throughout the educational program and reinforced every day when students are providing patient care (Fig. 4) (Forrest, 2006). However, it has been argued that not all dentists, including dental educators, are trained for critical appraisal of the literature, the five-step EBD process, and the use of secondary sources (Rabb-Waytowich, 2009a, Werb and Matear, 2004, Forrest, 2006, Levine et al., 2008, Moskowitz, 2009, Sabounchi et al., 2013, Richards, 2006). Critical appraisal skills (i.e. basic numeracy, electronic database searching, and the ability systematically to ask questions of a research study) are prerequisites for competence in EBD (Horsley et al., 2011, Parkes et al., 2001), and dentists need to be able to apply them to everyday clinical practice (Green, 2000). Moreover, dental educators have to consider that not all dental treatment outcomes have been researched with RCTs (Kao, 2006a, Kao, 2006b, Kao, 2011).

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the major elements of treatment plan model for integrating EBD into dental education (adapted from Forrest, 2006).

7. Conclusion and recommendations

To the authors’ knowledge, there is a lack of guidelines within dentistry regarding EBD and KT and consequently, most dental care is not based on validated research. The findings from this paper call for future development of clinical guidelines and greater EBP and KT. Many dental clinicians and educators are undertrained in critical appraisal making, the five-step EBD process, and the skilled use of secondary sources. Furthermore, many EBD-trained dental professionals are not implementing EBP due to its complex nature and their restricted time. For this reason, better access to EBD tools and time-efficient resources could be a solution for more widely applying an EBP. Therefore, online platforms for better access (affordable or open access) to EBD should be developed (e.g. http://ebhnow.com/) and improved in order to translate the evidence to clinic in a more rapid and efficient way (information rich but short summaries).

Conflict of interest

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

Both authors, KIA and MKA, are grateful to Dr. Faleh Tamimi, an Implant Research Program Director at McGill University & Canada Chair Translational Research, for revising part of this manuscript.

The first author, KIA, acknowledges the Network for Oral and Bone Health Research (RSBO – Quebec, Canada), and the Alpha Omega Foundation of Canada, for their support.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Anon., 1981. How to read clinical journals: I. why to read them and how to start reading them critically. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 124(5), 555–558. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Anon., 1994. Evidence-based health care: a new approach to teaching the practice of health care. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. J. Dent. Educ. 58(8), 648–653. [PubMed]

- Anon., 2009. Evidence-based review of clinical studies on restorative dentistry. J. Endod. 35(8), 1111–1115. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Anon., 2014. More about knowledge translation at CIHR. Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

- Abt E., Pihlstrom B.L. A practitioner's guide to developing critical appraisal skills: the fundamentals of research. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2012;143(1):54–56. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abt E., Bader J.D., Bonetti D. A practitioner's guide to developing critical appraisal skills: translating research into clinical practice. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2012;143(4):386–390. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afrashtehfar K.I. The all-on-four concept may be a viable treatment option for edentulous rehabilitation. Evid. Based Dent. 2016;17(2):56–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6401173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afrashtehfar K.I. Evidence regarding lingual fixed orthodontic appliances' therapeutic and adverse effects is insufficient. Evid. Based Dent. 2016;17(2):54–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6401172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afrashtehfar K.I., Ahmadi M., Emami E., Abi-Nader S., Tamimi F. Failure of single-unit restorations on root filled posterior teeth: a systematic review. Int. Endod. J. 2016 doi: 10.1111/iej.12723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afrashtehfar K.I., Eimar H., Yassine R., Abi-Nader S., Tamimi F. Evidence-based dentistry for planning restorative treatments: barriers and potential solutions. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2016 doi: 10.1111/eje.12208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afrashtehfar K.I., Brägger U., Treviño-Santos A., de Souza R.F. Letters to the editor. Evid. Based Dent. 2017;18(1):2. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6401212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J.D. Need for evidence-based practice in prosthodontics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2000;83(1):58–65. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(00)70089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azarpazhooh A., Mayhall J.T., Leake J.L. Introducing dental students to evidence-based decisions in dental care. J. Dent. Educ. 2008;72(1):87–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader J., Ismali A., Clarkson J. Evidence-based dentistry and the dental research community. J. Dent. Res. 1999;78(9):1480–1483. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780090101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balas E.A., Weingarten S., Garb C.T., Blumenthal D., Boren S.A., Brown G.D. Improving preventive care by prompting physicians. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000;160(3):301–308. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayne S.C., Fitzgerald M. Evidence-based dentistry as it relates to dental materials. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2014;35(1):18–24. quiz 25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin P., DPBRN Collaborative Group Promoting evidenced-based dentistry through “the dental practice-based research network”. J. Evid. Dent. Pract. 2009;9(4):194–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidra A.S. Evidence-based prosthodontics: fundamental considerations, limitations, and guidelines. Dent. Clin. North Am. 2014;58(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brignardello-Petersen R., Carrasco-Labra A., Glick M., Guyatt G.H., Azarpazhooh A. A practical approach to evidence-based dentistry: IV: how to use an article about harm. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2015;146(2) doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2014.12.002. 94–101.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brignardello-Petersen R., Carrasco-Labra A., Glick M., Guyatt G.H., Azarpazhooh A. A practical approach to evidence-based dentistry: III: how to appraise and use an article about therapy. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2015;146(1) doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2014.11.010. 42–49.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brignardello-Petersen R., Carrasco-Labra A., Glick M., Guyatt G.H., Azarpazhooh A. A practical approach to evidence-based dentistry: V: how to appraise and use an article about diagnosis. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2015;146(3) doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2015.01.011. 184–191.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco-Labra A., Brignardello-Petersen R., Glick M., Guyatt G.H., Azarpazhooh A. A practical approach to evidence-based dentistry: VI: How to use a systematic review. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2015;46(4) doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2015.01.025. 255–265.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco-Labra A., Brignardello-Petersen R., Glick M., Guyatt G.H., Neumann I., Azarpazhooh A. A practical approach to evidence-based dentistry: VII: How to use patient management recommendations from clinical practice guidelines. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2015;146(5) doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2015.03.015. 327–336.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiappelli F., Prolo P., Newman M., Cruz M., Sunga E., Concepcion E., Edgerton M. Evidence-based practice in dentistry: benefit or hindrance. J. Dent. Res. 2003;82(1):6–7. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- C.O.D.A., 2015. Accreditation standards for dental education programs. American Dental Association: Commission on Dental Accreditation, Chicago.

- Clarkson J.E., Bonetti D. Why be an evidence-based dentistry champion? J. Evid. Dent. Pract. 2009;9(3):145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D.J., Jaeschke R., Guyatt G.H., Journal Club of the Hamilton Regional Critical Care Group Critical appraisal of therapeutic interventions in the intensive care unit: human monoclonal antibody treatment in sepsis. J. Intensive Care Med. 1992;7(6):275–282. doi: 10.1177/088506669200700601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter I.D. Evidence-based dentistry and health services research: is one possible without the other? J. Dent. Educ. 2001;65(8):714–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D., O'Brien M.A.T., Freemantle N., Wolf F.M., Mazmanian P., Taylor-Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education - do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA. 1999;282(9):867–874. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group, 1992. Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA 268(17), 2420–2425. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Faggion C.M., Jr., Tu Y.K. Evidence-based dentistry: a model for clinical practice. J. Dent. Educ. 2007;71(6):825–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer A.P., Legare F., Turcot L., Grimshaw J., Harvey E., McGowan J.L., Wolf F. Printed educational materials: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008;16(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004398.pub2. CD004398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest J.L. Treatment plan for integrating evidence-based decision making into dental education. J. Evid. Dent. Pract. 2006;6(1):72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillette J. Evidence-based dentistry for everyday practice. J. Evid. Dent. Pract. 2008;8(3):144–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasziou P., Chalmers I., Altman D.G., Bastian H., Boutron I., Brice A., Jamtvedt G., Farmer A., Ghersi D., Groves T., Heneghan C., Hill S., Lewin S., Michie S., Perera R., Pomeroy V., Tilson J., Shepperd S., Williams J.W. Taking healthcare interventions from trial to practice. BMJ. 2010;341:c3852. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham I.D., Logan J., Harrison M.B., Straus S.E., Tetroe J., Caswell W., Robinson N. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham I.D., Tetroe J. How to translate health research knowledge into effective healthcare action. Healthc. Q. 2007;10(3):20–22. doi: 10.12927/hcq..18919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham I.D., Tetroe J., KT Theories Research Group Some theoretical underpinnings of knowledge translation. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2007;14(11):936–941. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M.L. Evidence-based medicine training in graduate medical education: past, present and future. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2000;6(2):121–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2000.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T., Howick J., Maskrey N., Evidence Based Medicine Renaissance Group Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ. 2014;348:g3725. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw J.M., Eccles M.P., Lavis J.N., Hill S.J., Squires J.E. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R. Successes and failures in the implementation of evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice. Med. Care. 2001;39(8):II46–II54. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108002-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, I.S., 2013. Moving from knowledge to practice: is it time to move from teaching evidence-based medicine (EBM) to knowledge translation competency? Perspect. Med. Educ. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ho K., Chockalingam A., Best A., Walsh G. Technology-enabled knowledge translation: building a framework for collaboration. CMAJ. 2003;168(6):710–711. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsley T., Hyde C., Santesso N., Parkes J., Milne R., Stewart R. Teaching critical appraisal skills in healthcare settings. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011;(11) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001270.pub2. CD001270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail A.I., Bader J.D., ADA Council on Scientific Affairs and Division of Science; Journal of the American Dental Association Evidence-based dentistry in clinical practice. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2004;135(1):78–83. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis J.P. Evolution and translation of research findings: from bench to where? PLoS Clin. Trials. 2006;1(7):e36. doi: 10.1371/journal.pctr.0010036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R.T., Dickersin K. Publication bias against negative results from clinical trials: three of the seven deadly sins. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2007;3(11):590–591. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimbux N.Y. Evidence-based dentistry. J. Dent. Educ. 2013;77(2):123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimbux N.Y. Evidence-based dental education and systematic reviews. J. Dent. Educ. 2015;79(1):3–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao R.T. The challenges of transferring evidence-based dentistry into practice. J. Evid. Dent. Pract. 2006;6(1):125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao R.T. The challenges of transferring evidence-based dentistry into practice. J. Calif. Dent. Assoc. 2006;34(6):433–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao R.T. The challenges of transferring evidence-based dentistry into practice. Tex. Dent. J. 2011;128(2):193–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok V., Caton J.G., Polson A.M., Hunter P.G. Application of evidence-based dentistry: from research to clinical periodontal practice. Periodontol 2000. 2012;59(1):61–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A.E., Bebermeyer R.D., Chen J.W., Davis D., Harty C. Development of an interdisciplinary course in information resources and evidence-based dentistry. J. Dent. Educ. 2008;72(9):1067–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDermid J.C., Graham I.D. Knowledge translation: putting the “practice” in evidence-based practice. Hand Clin. 2009;25(1):125–143. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinho V.C., Richards D., Niederman R. Variation, certainty, evidence, and change in dental education: employing evidence-based dentistry in dental education. J. Dent. Educ. 2001;65(5):449–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall T.A., Straub-Morarend C.L., Qian F., Finkelstein M.W. Perceptions and practices of dental school faculty regarding evidence-based dentistry. J. Dent. Educ. 2013;77(2):146–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margaliot Z., Chung K.C. Systematic reviews: a primer for plastic surgery research. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2007;120(7):1834–1841. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000295984.24890.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlone P., Watt R., Sheiham A. Evidence-based dentistry: an overview of the challenges in changing professional practice. Br. Dent. J. 2001;190(12):636–639. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn E.A., Asch S.M., Adams J., Keesey J., Hicks J., DeCristofaro A., Kerr E.A. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348(26):2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D.M. Evidence-based dentistry: mapping the way from science to clinical guidance. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2008;139(11):1444–1446. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz E.M. Evidence-based dentistry for you and me. The challenge of using a new educational tool. NY State Dent. J. 2009;75(6):48–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murad M.H., Montori V.M., Ioannidis J.P., Jaeschke R., Devereaux P.J., Prasad K., Neumann I., Carrasco-Labra A., Agoritsas T., Hatala R., Meade M.O., Wyer P., Cook D.J., Guyatt G. How to read a systematic review and meta-analysis and apply the results to patient care: users' guides to the medical literature. JAMA. 2014;312(2):171–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederman R., Badovinac R. Tradition-based dental care and evidence-based dental care. J. Dent. Res. 1999;78(7):1288–1291. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780070101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederman R., Clarkson J., Richards D. The Affordable Care Act and evidence-based care. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2011;142(4):364–367. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunbosun O.A., Edouard L., Pierson R.A. Physicians' attitudes toward evidence based obstetric practice: a questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1998;316(7128):365–366. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7128.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes J., Hyde C., Deeks J., Milne R. Teaching critical appraisal skills in health care settings. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2001;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001270. CD001270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitts N. Understanding the jigsaw of evidence-based dentistry: 1. Introduction, research and synthesis. Evid. Dent. 2004;5(1):2–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitts N. Understanding the jigsaw of evidence-based dentistry. 3. Implementation of research findings in clinical practice. Evid. Dent. 2004;5(3):60–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitts N. Understanding the jigsaw of evidence-based dentistry. 2. Dissemination of research results. Evid. Dent. 2004;5(2):33–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabb-Waytowich D. You ask, we answer: evidence-based dentistry: Part 1. An overview. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2009;75(1):27–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabb-Waytowich D. Evidence-based dentistry: Part 2. Finding the research. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2009;75(3):191–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards D., Lawrence A. Evidence based dentistry. Br. Dent. J. 1995;179(7):270–273. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards D. Evidence-based dentistry–a challenge for dental education. Evid. Dent. 2006;7(3):59. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg W.M., Sackett D.L. On the need for evidence-based medicine. Therapie. 1996;51(3):212–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett D.L., Rosenberg W.M., Gray J.A., Haynes R.B., Richardson W.S. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabounchi S.S., Nouri M., Erfani N., Houshmand B., Khoshnevisan M.H. Knowledge and attitude of dental faculty members towards evidence-based dentistry in Iran. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2013;17(3):127–137. doi: 10.1111/eje.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi R. Evidence-based dentistry: achieving a balance. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2010;141(5):496–497. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salbach N.M. Knowledge translation, evidence-based practice, and you. Physiother. Can. 2010;62(4):293–297. doi: 10.3138/physio.62.4.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrett D.C. Evidence-based dentistry and dental education: meeting today's challenges to prepare tomorrow's dentists. Tex. Dent. J. 2004;121(5):390–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster M.A., McGlynn E.A., Brook R.H. How good is the quality of health care in the United States? 1998. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):843–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seals R.R., Jr., Jones J.D. Evidence-based practice in removable prosthodontics. Tex. Dent. J. 2003;120(12):1138–1145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears E.D., Burns P.B., Chung K.C. The outcomes of outcome studies in plastic surgery: a systematic review of 17 years of plastic surgery research. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2007;120(7):2059–2065. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000287385.91868.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah H.M., Chung K.C. Archie Cochrane and his vision for evidence-based medicine. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009;124(3):982–988. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b03928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus, S., Tetroe, J., Graham, I.D., Leung, E. Knowledge to Action: What It Is and What It Isn’t. CIHR IRSC.

- Sutherland S.E. The building blocks of evidence-based dentistry. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2000;66(5):241–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland S.E. Evidence-based dentistry: Part V. Critical appraisal of the dental literature: papers about therapy. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2001;67(8):442–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland S.E. Evidence-based Dentistry: Part VI. Critical Appraisal of the Dental Literature: Papers About Diagnosis, Etiology and Prognosis. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2001;67(10):582–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spallek H., Song M., Polk D.E., Bekhuis T., Frantsve-Hawley J., Aravamudhan K. Barriers to implementing evidence-based clinical guidelines: a survey of early adopters. J. Evid. Dent. Pract. 2010;10(4):195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetroe, J., 2007. Knowledge Translation at the Canadian Institutes of Health Research: A Primer. FOCUS.

- Werb S.B., Matear D.W. Implementing evidence-based practice in undergraduate teaching clinics: a systematic review and recommendations. J. Dent. Educ. 2004;68(9):995–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westfall J.M., Mold J., Fagnan L. Practice-based research–“Blue Highways” on the NIH roadmap. JAMA. 2007;297(4):403–406. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood M.R., Vermilyea S.G., Committee on Research in Fixed Prosthodontics of the Academy of Fixed Prosthodontics A review of selected dental literature on evidence-based treatment planning for dental implants: report of the Committee on Research in Fixed Prosthodontics of the Academy of Fixed Prosthodontics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2004;92(5):447–462. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younossi Z., Guyatt G. Evidence-based medicine: a method for solving clinical problems in hepatology. Hepatology. 1999;30(4):829–832. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zander S., Kunkes E.L., Schuster M.E., Schumann J., Weinberg G., Teschner D., Jacobsen N., Schlogl R., Behrens M. The role of the oxide component in the development of copper composite catalysts for methanol synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013;52(25):6536–6540. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]