Abstract

Purpose

To determine characteristics of Chinese men undergoing initial prostate biopsy and to evaluate the relationship between PSA levels and PCa/HGPCa detection in a large Chinese multicenter cohort.

Materials and Methods

13,904 Urology outpatients received biopsy for indications as following were included in this retrospective study: PSA levels of > 4.0 ng/mL or PSA levels of <4.0 ng/ml but with abnormal DRE results. The PSA measurements were performed in accordance with the standard procedures at the respective institutions. The type of assay used was documented and recalibrated to the WHO standard.

Results

The incidence of PCa and HGPCa were lower in the Chinese cohort than Western cohorts at any given PSA level. Around 25% of patients with PSA levels of 4.0-10.0 ng/mL were found to have PCa compared to approximately 40% in US clinical practice. Moreover, the risk curves were generally flatter than that of the Western cohorts, that is, risk did not increase as rapidly with higher PSA.

Conclusions

The relationship between PSA level and prostate cancer risk differs importantly between Chinese and Western populations, with overall lower risk in the Chinese cohort. Further research should explore whether environmental or genetic differences explain these findings or whether they result from unmeasured differences in screening or benign prostate disease. Caution is required for the implementation of prostate cancer clinical decision rules or prediction models to men in China, or other Asian countries with similar genetic and environmental backgrounds.

Keywords: Biopsy, Chinese population, Detection rate, Prostate neoplasms, Prostate-specific antigen

Introduction

The incidence of prostate cancer (PCa) in East Asian countries is much lower than Western countries1. That said, the incidence rate of PCa in China has been rapidly increasing, likely due to longer life expectancy and Westernized lifestyles associated with dramatic economic growth and sociocultural changes2.

Data from the Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group (PBCG) has demonstrated the relationship between prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels and PCa and high-grade PCa (HGPCa, defined as Gleason Score sum 7 or higher) varied between cohorts depending on characteristics such as biopsy technique, and whether biopsy decisions involved clinical work-up or took place in all men with elevated PSA3. The PBCG was restricted to cohorts from Europe and North America. There are differences between Asian and Western populations4 and the relationship between PSA level and PCa detection rate may thus differ between these populations as summarized in a recent review.5 In this study, we aim to determine the characteristics of Chinese men undergoing initial prostate biopsy and evaluate the relationship between PSA level and the detection rate of PCa and HGPCa in a nationwide, multicenter biopsy cohort.

Materials and methods

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at each participating hospital. We retrospectively collected information from consecutive patients undergoing initial transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) guided or transperineal prostate biopsies in 22 tertiary hospitals in 10 provinces across China between January 2010 and December 2013. All hospitals but four are listed among the “top 100 hospitals” in China6, ensuring high quality pathology review. MRI was not routinely used in any center for prostate cancer diagnosis.

Urology outpatients received biopsy for PSA levels of > 4.0 ng/mL regardless of digital rectal examination (DRE) results or PSA levels of <4.0 ng/ml but with abnormal DRE results, defined as nodularity on palpation. Patients present as urology outpatients for lower urinary tract symptoms, other urological symptoms or self-initiated health check-ups. PSA and DRE are given to all men of appropriate age. Decision to biopsy is based on clinical judgment, taking into account factors such as prostate volume, symptoms and, in some cases, free-to-total PSA ratio. Patients with suspicion of urinary tract infections, urinary retention, or instrumentation or catheterization of the urethra within two weeks were excluded, as were those who had received 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors in the last two months. TRUS-measured prostate volume was calculated with D1×D2×D3×(π/6). The PSA measurements were performed in accordance with the standard assays and procedures at the respective institutions with recalibration to the World Health Organization (WHO) standard (PSA-WHO 96/670) using the appropriate correction factor.

The probability of biopsy-detected PCa and HGPCa at a given PSA level was calculated by locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS)7, allowing comparability between the current findings and prior reports from this group3. Patients with PSA levels of < 100 ng/mL were included in the calculation of the risk curve, but risk curves were displayed only for PSA values of ≤ 10.0 ng/mL. The distribution of PSA levels in Chinese and Western cohorts was calculated using kernel density methods and excluded the clinical trial cohorts, on the grounds that we were interested in the PSA distributions of patients presenting in clinical practice. All analyses were conducted using Stata 13.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

Of the 17,295 patients initially reviewed, 2,104 were excluded for elevated white blood cells in urine within two weeks of biopsy, 1,033 excluded for taking 5-alpha reductase inhibitors within two months before the PSA test, 152 excluded for repeat biopsies and 102 excluded for recent urinary catheter manipulation. The final data set included 13,904 biopsies with 6,123 cancers detected. Among included patients, 13,203 cases were due to PSA levels of > 4.0 ng/mL regardless of DRE results and 701 cases were due to PSA levels of <4.0 ng/ml but with abnormal DRE results. The study population is representative of the routine clinical care in China. The distributions of PSA levels in Chinese and Western clinical cohorts are shown in Figure 1. PSA levels at presentation are clearly much higher in the Chinese cohorts. As expected, PCa patients were older (median, 72 vs. 68 years, p < 0.0001), with higher PSA levels (median 26.1 vs. 10.4 ng/mL, p < 0.0001) and smaller prostate volume (median 40.2 vs. 47.5 mL, p < 0.0001) (Table 1). HGPCa accounted for 77% of diagnosed PCa, with 38% and 39% of patients having a Gleason score = 7 or ≥ 8, respectively (Table 2). Among the patients who were diagnosed with PCa, 58% had PSA levels of > 20 ng/mL, 23% had PSA levels of 10-20 ng/mL, whereas only 20% had PSA levels of < 10 ng/mL (Table 3). Although the number of patients with PSA < 4 ng / mL was low in relative terms (5.1%), it constitutes a large number of patients in absolute terms (n=701).

Figure 1.

Distribution of PSA among men with clinical indication for prostate biopsy. Black: PBCG cohorts; Red: Chinese cohort

Table 1. Clinical variables in prostate cancer and negative biopsy subjects.

| Prostate Cancer | Negative Biopsy | All | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of subjects (n) | 6123 | 7781 | 13904 | |

| Age, (years) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 72 (66-77) | 68 (61-74) | 70.0 (63-76) | < 0.0001* |

| PSA, (ng/mL) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 26.1 (11.5-88.0) | 10.4 (6.8-16.9) | 13.5 (8.1-32.1) | < 0.0001* |

| Percent Free PSA, (%) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 12.0 (8.0-18.0) | 15.0 (10.0-22.0) | 14.0 (9.0-20.6) | < 0.0001* |

| Prostate Volume, (mL) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 40.2 (29.2-57.6) | 47.5 (32.9-72.5) | 44.0 (31.1-65.5) | < 0.0001* |

| No. of Biopsy Cores | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 10 (8-12) | 10 (8-12) | 10 (8-12) | < 0.0001* |

| Biopsy pathway, cases (%) | ||||

| Transrectal ultrasound-guided | 4647 (76%) | 6162 (79%) | 10809 (78%) | 0.16# |

| Transperineal | 1476 (24%) | 1619 (21%) | 3095 (22%) |

Mann-Whitney U test;

Chi-square test.

SD: Standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; PSA: Prostate Specific Antigen

Table 2. Comparison of clinical characteristics of the Chinese biopsy cohort and Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group cohorts.

| Name of cohort | Location | Type of cohort |

Indication for biopsy | Biopsy scheme | Age (years) | PSA (ng/mL) | Prostate volume (mL) |

Prostate cancer (%) |

Biopsy Gleason grade | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| ≤6 | 7 | ≥8 | NA | |||||||||

| Chinese Biopsy Cohort | China, Nationwide | Clinical | PSA ≥4ng/mL or abnormal DRE; Positive ultrasound or MRI result | 6-, 8-, 10-, 12-core and saturation biopsy (≥22 cores) takes 11%, 19%, 28%, 36% and 4%, respectively. | 70 (63,76) | 13.5 (8.1-32.1) | 44 (31, 65) | 6123 (44%) | 1295 (21%) | 2319 (38%) | 2371 (39%) | 138 (2.3%) |

| Cleveland Clinic | Cleveland, OH | Clinical | Elevated PSA, abnormal DRE,rapid rise in PSA | Primarily >=8-core | 64 (58, 69) | 5.75 (4.31, 8.50) | 42 (30, 58) | 1,292 (39%) | 669 (52%) | 478 (37%) | 145 (11%) | 0 (0%) |

| Durham VA | Durham, NC | Clinical | Elevated PSA, abnormal DRE | 6, 10, or 10–15-core* | 63 (59, 66) | 4.35 (3.50, 6.20) | NA | 2,570 (35%) | 1,703 (66%) | 729 (28%) | 138 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| ProtecT | United Kingdom | Screening§ | PSA ≥3 ng/mL | 6, 10 or 12-core | 63 (57, 68) | 4.21 (2.80, 6.79) | 35 (27, 46) | 1,562 (28%) | 911 (58%) | 319 (20%) | 332 (21%) | 195 (12%) |

| Tyrol | Austria | Screening§ | PSA ≥1.25 ng/mL, percent free PSA, abnormal DRE | 10-core | 64 (59, 69) | 5.17 (3.71, 8.27) | NA | 1,148 (47%) | 606 (53%) | 387 (34%) | 155 (14%) | 14 (1%) |

| ERSPC Göteborg Round 1 | Sweden | Screening | PSA ≥3 ng/mL | 6-core | 61 (58, 64) | 4.65 (3.68, 6.72) | 39 (30, 51) | 192 (26%) | 152 (79%) | 33 (17%) | 7 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| ERSPC Göteborg Round 2-6 | Sweden | Screening | PSA ≥3 ng/mL | 6-core | 63 (61, 67) | 3.56 (3.17, 4.26) | 37 (30, 47) | 322 (26%) | 269 (84%) | 45 (14%) | 8 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| ERSPC Rotterdam Round 1 | The Netherlands | Screening | PSA ≥3 ng/mL or PSA ≥4 ng/mL, depending on year | 6-core | 66 (62, 70) | 5.03 (3.93, 7.31) | 46 (35, 60) | 800 (28%) | 508 (63%) | 234 (29%) | 58 (7%) | 6 (1%) |

| ERSPC Rotterdam Round 2-3 | The Netherlands | Screening | PSA ≥3 ng/mL or PSA ≥4 ng/mL | 6-core | 67 (63, 71) | 3.45 (2.94, 4.33) | 44 (35, 54) | 388 (26%) | 297 (77%) | 78 (20%) | 13 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| ERSPC Tarn Round 1 | France | Screening | PSA ≥3 ng/mL | Primarily 10 to 12-core | 64 (60, 67) | 4.45 (3.53, 5.98) | NA | 96 (32%) | 42 (44%) | 37 (39%) | 17 (18%) | 3 (3%) |

| SABOR | San Antonio, TX | Screening | PSA ≥2.5 ng/mL, abnormal DRE, or family history | 10–12-core | 63 (58, 68) | 3.42 (1.44, 5.40) | NA | 133 (34%) | 95 (71%) | 28 (21%) | 10 (8%) | 3 (2%) |

| PCPT | US | Screening | PSA ≥4ng/mL or abnormal DRE for “for cause” biopsies; end of study biopsy offered to all men | Primarily 6 core | ||||||||

ERSPC: European Randomized study of Screening for Prostate Cancer; ProtecT: Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment; SABOR: San Antonio Center of Biomarkers of Risk for Prostate Cancer; PCPT: Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. Data were not received from the PCPT for this study, the relationship between risk and PSA for the PCPT was obtained using the PCPT risk calculator. §Not formally established as a screening cohort, but involved population-based PSA testing.

Table 3. Prostate cancer and high-grade prostate cancer detection rate by PSA level, age and biopsy scheme.

| No. of Patients, (%) |

PCa detection rate, (%) |

HGPCa detection rate, (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| PSA, (ng/mL) | |||

|

| |||

| 0-2 | 318 (2.3%) | 19% | 6.3% |

| 2-4 | 383 (2.8%) | 20% | 10% |

| 4-10 | 4124 (29%) | 26% | 11% |

| 10-20 | 4014 (29%) | 35% | 19% |

| 20-50 | 2587 (19%) | 55% | 35% |

| 50-100 | 2478 (18%) | 86% | 72% |

|

| |||

| Age, (years) | |||

|

| |||

| <40 | 21 (0.15%) | 19% | 14% |

| 40-54 | 663 (4.8%) | 26% | 16% |

| 55-69 | 5856 (42%) | 36% | 23% |

| 70-75 | 3386 (24%) | 49% | 31% |

| >75 | 3470 (25%) | 57% | 39 % |

| Missing | 508 (3.7%) | 40% | 31% |

|

| |||

| Biopsy Scheme | |||

|

| |||

| 6-Cores | 1748 (12%) | 59% | 49% |

| 8-Cores | 2640 (19%) | 41% | 31% |

| 10-Cores | 3920 (28%) | 40% | 28% |

| 12-cores | 4989 (36%) | 41% | 22% |

| Saturation | 607 (4.4%) | 50% | 30% |

|

| |||

| Total | 13904 | 44% | 28% |

PCa detection rates

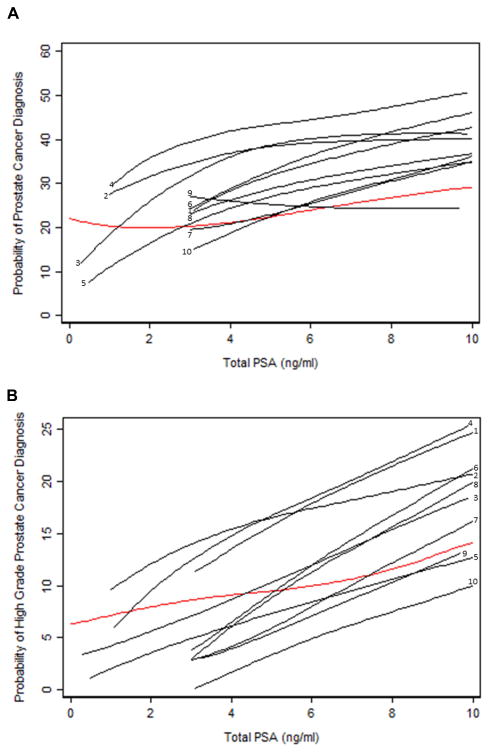

Overall, cancer was found in 44% of biopsies. The relationship between PSA and PCa is presented (Table 3, Figure 2A). Two features of this risk curve are notable. First, it is relatively flat, especially at low PSA levels. Risk of PCa did not change substantially in PSA range of 0-4 ng/mL and the risk increased by only 6% in absolute terms from PSA of 4 ng/mL to 10 ng/mL. Second, for PSAs above about 2 ng/mL, risk is lower in the Chinese cohort than almost any other cohorts, and substantially lower than the two clinical cohorts in PBCG. At a PSA level of 4 ng/mL, risk of cancer was 21% in this Chinese cohort versus 38% and 43% in the Cleveland Clinic and Durham Veteran Affairs Hospital (Durham VA), respectively (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of PCa (A) and HGPCa (B) by PSA level. Black: PBCG cohorts (1 Tarn; 2 CCF; 3 Sabor; 4 Durham VA; 5 Tyrol; 6 ProtecT; 7 Rotterdam Round 1; 8 Rotterdam Subsequent; 9 Goteborg Subsequent; 10 Goteborg Round 1). Red: Chinese cohort.

HGPCa detection rates

Overall, 29% of patients were diagnosed with HGPCa, with rates of 11% and 19% in patients with a PSA level of 4.0-10.0 ng/mL and 10.0-20.0 ng/mL respectively. The relationship between PSA and risk of HGPCa is shown in Figure 2B. The shape of the PSA-HGPCa risk curve is quite flat up to a PSA of 8 ng/mL, with detection rates increasing only from 8% at 2 ng/mL to 12% at 8 ng/mL. In contrast, for most cohorts, the risk of HGPCa rises two or three fold between a PSA of 2 ng/ mL and 8 ng/ mL (Supplementary Table 2). As a result, the proportion of cancers that are high-grade does not rise importantly with PSA (Figure 3). In comparison, for other cohorts, the likelihood that a positive biopsy reflects HGPCa increases rapidly with PSA.

Figure 3.

Proportion of cancers that were HGPCa by PSA level. Black: PBCG cohorts (1 Tarn; 2 CCF; 3 Sabor; 4 Durham VA; 5 Tyrol; 6 ProtecT; 7 Rotterdam Round 1; 8 Rotterdam Subsequent; 9 Goteborg Subsequent; 10 Goteborg Round 1). Red: Chinese cohort.

Detection rate in subgroups by age groups and biopsy schemes

Patients aged 55-69 years old accounted for about 90% of participants in European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) cohorts 8. The cancer detection rate of this age group in this study was lower than the entire cohort (36% vs. 44%, p < 0.0001, Chi-squared test). The predicted detection rate was approximately 17% and 25% for PSA levels of 4.0 ng/mL and 10.0 ng/mL in this age group, respectively.

Most biopsies were performed based on systematic 8-, 10- and 12-core schemes with PCa detection rate of 41%, 40% and 41%, respectively (Table 1). No center applied sextant biopsies as the predominant scheme; however, some physicians used sextant biopsy for patients with higher risk, such as higher PSA values, suspicious ultrasound results or abnormal DREs. Thus, sextant biopsies yielded higher detection rates than those of the entire cohort (64% vs. 41%, p < 0.0001). Saturation biopsies detected more PCa cases in the PSA level 4.0-10.0 ng/mL, but HGPCa detection rates were similar to the 8-, 10- and 12-core schemes.

The relationship between prostate volume and PCa risk

As an exploratory analysis, we used logistic regression to determine whether the relationship between prostate volume and PCa risk varied between the Chinese cohorts and PBCG cohorts after adjusting for age. Although we saw a statistically significant differences between Western and Chinese cohorts (p=0.034), these differences were not clinically meaningful. For instance, risk of high grade disease decreased from 10% to 7.5% in Western cohorts as volume increased from 40 to 60mL; the equivalent risks for the Chinese cohorts were 25% to 20%, that is, a relative risk of 0.8 versus 0.75.

Discussion

Our results indicated that Chinese men tend to undergo biopsy at a later stage, with higher PSA levels and Gleason scores. The current cohort was quite unique compared with PBCG cohorts in terms both of the risk of PCa and the shape of the risk curve 3. The detection rates of PCa and HGPCa were lower in the Chinese cohort than Western cohorts at any given PSA level. Moreover, the risk curves were generally flatter than that of the Western cohorts, that is, risk did not increase as rapidly with higher PSA.

Possible explanations of these findings fall into one of two classes. First, it may be artifact of the study population and clinical decision-making, such as age, number of biopsy cores, pathology or perhaps most obviously, selection criteria for biopsy. The other explanation is biological differences between the Chinese and the Western populations, due to either environmental or genetic factors.

With respect to the selection criteria for biopsy, risk is increased if urologists use clinical criteria additional to PSA in order to determine a biopsy indication. However, risk in the Chinese cohort at a given PSA level is less than the risk in the Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT), Göteborg and Rotterdam cohorts, all of which involved biopsy for elevated PSA irrespective of other risk factors. Any differences in biopsy selection would therefore tend to increase risk at a given PSA in the Chinese cohorts, the opposite of the effect seen. Moreover, the PCa detection rate in a largest screening study in China was 11% for patients with PSA 4-10 ng/ml, even lower than what we report here9. Hence, selection criteria for biopsy are unlikely to explain the observed differences.

Second, the age of patients in the Chinese cohort (median 70; quartiles 73, 76) was higher than that of all Western cohorts (median from 61 to 67 years) 3. As the incidence of PCa, and HGPCa in particular, increases with age, we would expect that the detection rate in the Chinese cohort would be even lower if standardized for age. In an analysis restricted to the age group of the ERSPC participants study, we found again lower risk in the Chinese cohort. Age is therefore not a plausible explanation either.

Third, prostate volume was higher in the Chinese cohorts. This could theoretically lead to a higher rate of missing PCa at biopsy and thus lower PCa detection rate in the Chinese cohort. However, this would not explain differences in the shape of the risk curve.

Fourth, prior exposure to PSA testing tends to lower both overall risk and to flatten the risk curve. However, again, the results are in the opposite direction to that expected, with more prior screening in Western cohorts, but lower risk and a flatter risk curve in the Chinese cohorts.

In addition, there may be differences in pathologic grading between the Chinese and PBCG cohorts. Indeed, this would be expected given that the Chinese cohort is more recent and that grading practices have changed over time, specifically, that many of what used to be described as Gleason 6 tumors would now be described as Gleason 710, as the 2005 modified Gleason pattern 4 includes most cribriform patterns and poorly formed glands.11 However, while this might explain differences in the absolute risk of HGPCa reported here, it would not explain differences in the shape of the risk curve. It seems highly unlikely that there was a gross under-calling of PCa by Chinese pathologists.

There were differences in screening across these included cohorts (Table 2). PSA screening is only rarely performed in China and there is poor acceptance of screening: only 10% of patients are willing to take PSA test, even in Hong Kong where people have better access to medical resources12.

Finally, close to 70% of the patients in the Chinese cohort received 10 or more biopsy cores, which was higher than that of ERSPC and Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) cohorts (primarily 6-core) and comparable to that of Cleveland Clinic (≥8-core) and Durham VA (6-, 10- and 12-core).

As such, none of above mentioned serves as good explanations for these findings. Indeed, in comparison to say, the ERSPC, detection rates in the Chinese cohort may have been even lower if all men were biopsied for elevated PSA, age was lower, the rate of prior screening similar and sextant biopsy used. We therefore hypothesize that genetic or environmental differences between the Chinese and Western populations led to a lower risk of cancer for a given PSA as well as differences in the shape of the risk curve. PSA elevation may be caused by both malignant and benign conditions, hence between-cohort differences in PCa risk at a given PSA may result from differences in the relative incidence of PCa compared to benign disease. As infection was an exclusion criterion, the incidence of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and chronic inflammation is of key interest. It has been reported that in both clinic13, 14 and at autopsy15 cohorts that the incidence of PCa is lower, but that of BPH similar between Asian and Western populations. One possible explanation for the reduced incidence of PCa in Asia is dietary: traditional East Asian food, such as high isoflavones16 and green tea17, has been linked to a lower incidence rate of PCa. Moreover, several studies have reported that the incidence of PCa in Asian immigrants to North America18-20 and European countries21-23 is substantially higher than their home countries, again suggesting a dietary explanation. Previous reports suggest that serum levels of total and bioavailable testosterone does not differ between the Chinese and Caucasians24, 25. As such we do not believe that differences in testosterone explain our results.

There are several limitations to our study. Data on DRE and family history were missing. PCa has historically been extremely rare in China1, 14 so we would expect a very low incidence of positive family history. Moreover, positive DRE or family history, this would lead to a bias in the opposite direction to that observed. In addition, this study is based on a clinical cohort. This issue should be recognized in making comparison with screening cohorts. There are also inherent limitations of multicenter studies, with biopsies performed by different urologists and slides reviewed by different pathologists. Yet while this effect is likely to add statistical noise, it is unlikely that it would lead to the large systematic differences observed here.

Conclusions

The relationship between PSA level and PCa risk varies importantly between Chinese and Western populations, with overall lower risk in the Chinese cohort. Our findings raise concerns about clinical decision rules - such as biopsying men with elevated PSA - or prediction models for clinical practice in China, or other Asian countries with similar genetic and environmental backgrounds. Further research should explore whether the differences observed between Western and Chinese can be explained in terms of environmental or genetic factors.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1 Predicted detection rate of prostate cancer at different PSA levels in the Chinese biopsy cohorts and Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group cohorts

Supplementary Table 2 Predicted detection rate of high-grade prostate cancer at different PSA levels in the Chinese biopsy cohorts and PBCG cohorts

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the Chinese Prostate Cancer Consortium that were not listed as authors for their assistance in concept, design and data collection of this program.

Grant Support: Supported in part by funds from the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University scheme of the Ministry of Education of China (NO.IRT1111, Yinghao Sun), the National Basic Research Program of China (2012CB518300, 2012CB518306, Yinghao Sun); and funds from David H. Koch provided through the Prostate Cancer Foundation, the Sidney Kimmel Center for Prostate and Urologic Cancers, P50-CA92629 SPORE grant from the National Cancer Institute to Dr. H Scher, the P30-CA008748 NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant to MSKCC and R01 CA179115 to Dr. A. Vickers.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- DRE

digital rectal examination

- Durham VA

Durham Veteran Affairs Hospital

- ERSPC

European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer

- HGPCa

high-grade PCa

- PBCG

Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group

- PCa

prostate cancer

- ProtecT

Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

The Chinese Prostate Cancer Consortium is: Yinghao Sun1, Yiran Huang2, Liping Xie3, Liqun Zhou4, Dalin He5, Qiang Ding6, Qiang Wei7, Pengfei Shao8, Ye Tian9, Zhongquan Sun10, Qiang Fu11, Lulin Ma12, Junhua Zheng13, Zhangqun Ye14, Dingwei Ye15, Danfeng Xu16, Jianquan Hou17, Kexin Xu18, Jianlin Yuan19, Xin Gao20, Chunxiao Liu21, Tiejun Pan22, Xu Gao1, Shancheng Ren1, Chuanliang Xu1.

Shanghai Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China.

Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, School of Medicine, Shanghai, China.

First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China.

Peking University First Hospital, Institute of Urology, Peking University, National Urological Cancer center, Beijing, China

First Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an, China.

Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China.

West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China.

The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China.

Huadong hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China.

Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People's Hospital, Shanghai, China.

Peking University Third Hospital, Beijing, China.

Tenth People's Hospital, Tongji University, Shanghai, China.

Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center and Department of Oncology, Shanghai, China.

Shanghai Changzheng Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China.

The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou, China.

Peking University People's Hospital, Beijing, China.

Xijing Hospital, The Fourth Military Medical University, Xi'an, China.

The 3rd Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China.

Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University. Guangzhou, China.

Wuhan General Hospital of Guangzhou Military Command, Wuhan, China.

The Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group is:

Andrew J. Vickers1, Monique J. Roobol2, Jonas Hugosson3, J. Stephen Jones4, Michael W. Kattan4, Eric Klein4, Freddie Hamdy5, David Neal6, Jenny Donovan7, Dipen J. Parekh8, Donna Ankerst9, George Bartsch10, Helmut Klocker10, Wolfgang Horninger10, Amine Benchikh11, Gilles Salama12, Arnauld Villers13, Steve J. Freedland14, Daniel M. Moreira14, Fritz H. Schröder2, Hans Lilja1, Angel M. Cronin15

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York

Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Goteborg, Sweden

Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

Oxford University, Oxford, United Kingdom

Cambridge University, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Bristol University, Bristol, United Kingdom

University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas

Technische Universitaet Muenchen, Munich, Germany

Innsbruck Medical University, Innsbruck, Austria

Hôpital Bichat-Claude Bernard, Paris, France

Centre Hospitalier Intercommunal Castres-Mazamet, Castres, France

Hôpital Huriez, CHRU Lille, Lille, France

Cedars Sinai, Lost Angeles, California

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by any author.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, S I, Ervik M. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. [accessed on 2015/08/28]. [Internet] Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center MM, Jemal A, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. International variation in prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates. Eur Urol. 2012;61:1079. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Roobol MJ, et al. The Relationship between Prostate-Specific Antigen and Prostate Cancer Risk: The Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16:4374. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ito K. Prostate cancer in Asian men. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11:197. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen R, Ren S, Yiu MK, et al. Prostate cancer in Asia: A collaborative report. Asian Journal of Urology. 2014;1:15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajur.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fudan University Hospital management institute. Top 100 hospitals in China. [accessed on 2014/12/12];2013 Available from: http://www.fudanmed.com/institute/

- 7.Cleveland WS. Robust Locally Weighted Regression and Smoothing Scatterplots. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1979;74:829. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otto SJ, Moss SM, Maattanen L, et al. PSA levels and cancer detection rate by centre in the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:3053. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuwahara M, Tochigi T, Kawamura S, et al. Mass screening for prostate cancer: a comparative study in Natori, Japan and Changchun, China. Urology. 2003;61:137. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helpap B, Egevad L. The significance of modified Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma in biopsy and radical prostatectomy specimens. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:622. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein JI, Allsbrook WC, Jr, Amin MB, et al. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1228. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000173646.99337.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.So WK, Choi KC, Tang WP, et al. Uptake of prostate cancer screening and associated factors among Chinese men aged 50 or more: a population-based survey. Cancer Biol Med. 2014;11:56. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lloyd SN, Kavanagh J, Chan PS, et al. A multicentre prospective study of prostatic volume in asymptomatic men in various continents. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 1997;1:97. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu FL, Xia TL, Kong XT. Preliminary study of the frequency of benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatic cancer in China. Urology. 1994;44:688. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(94)80207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zlotta AR, Egawa S, Pushkar D, et al. Prevalence of inflammation and benign prostatic hyperplasia on autopsy in Asian and Caucasian men. Eur Urol. 2014;66:619. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan L, Spitznagel EL. Soy consumption and prostate cancer risk in men: a revisit of a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1155. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng J, Yang B, Huang T, et al. Green tea and black tea consumption and prostate cancer risk: an exploratory meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63:663. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.570895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller BA, Chu KC, Hankey BF, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns among specific Asian and Pacific Islander populations in the U.S. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:227. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9088-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCracken M, Olsen M, Chen MS, Jr, et al. Cancer incidence, mortality, and associated risk factors among Asian Americans of Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese ethnicities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:190. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.4.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo W, Birkett NJ, Ugnat AM, et al. Cancer incidence patterns among Chinese immigrant populations in Alberta. J Immigr Health. 2004;6:41. doi: 10.1023/B:JOIH.0000014641.68476.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnold M, Razum O, Coebergh JW. Cancer risk diversity in non-western migrants to Europe: An overview of the literature. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2647. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metcalfe C, Patel B, Evans S, et al. The risk of prostate cancer amongst South Asian men in southern England: the PROCESS cohort study. BJU Int. 2008;102:1407. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linz B, Vololonantenainab CR, Seck A, et al. Population genetic structure and isolation by distance of Helicobacter pylori in Senegal and Madagascar. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lookingbill DP, Demers LM, Wang C, et al. Clinical and biochemical parameters of androgen action in normal healthy Caucasian versus Chinese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;72:1242. doi: 10.1210/jcem-72-6-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng I, Yu MC, Koh WP, et al. Comparison of prostate-specific antigen and hormone levels among men in Singapore and the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1692. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1 Predicted detection rate of prostate cancer at different PSA levels in the Chinese biopsy cohorts and Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group cohorts

Supplementary Table 2 Predicted detection rate of high-grade prostate cancer at different PSA levels in the Chinese biopsy cohorts and PBCG cohorts