Abstract

Background

Although epidemiological studies have reported positive associations between circulating urate levels and cardiometabolic diseases, causality remains uncertain.

Objective

Through a Mendelian randomization approach, we assessed whether serum urate levels are causally relevant in type-2 diabetes (T2D), coronary heart disease (CHD), ischemic stroke and heart failure.

Methods

We investigated 28 SNPs known to regulate serum urate levels in association with a range of vascular and non-vascular risk factors to assess pleiotropy. To limit genetic confounding, 14 SNPs found exclusively associated with serum urate levels were used in a genetic risk score to assess associations with the following cardiometabolic diseases (cases/controls): T2D (26,488/83,964), CHD (54,501/68,275), ischemic stroke (14,779/67,312) and heart failure (4,526/18,400). As a positive control, we also investigated our genetic instrument in 3,151 gout cases and 68,350 controls.

Results

Serum urate levels, raised by 1 standard deviation (SD) due to the genetic score, were not associated with T2D (odds ratio [OR] 0.95, 95% CI, 0.86–1.05), CHD (OR. 1.02, 95% CI, 0.92–1.12), ischemic stroke (OR. 0.99, 95% CI, 0.88–1.12), or heart failure (OR. Q1.07, 95% CI, 0.88–1.30). These results were in contrast with previous prospective studies that observed increased risks of T2D (OR. 1.25, 95% CI, 1.13–1.37), CHD (OR. 1.06, 95% CI, 1.03–1.09), ischemic stroke (OR. 1.17, 95% CI, 1.00–1.37), and heart failure (OR. 1.19, 95% CI, 1.17–1.21) for an equivalent increase in circulating urate levels. However, a 1 SD increase in serum urate levels due to the genetic score was associated with increased risk of gout (OR. 5.84, 95% CI, 4.56–7.49), which was directionally consistent with associations observed in previous epidemiological studies

Conclusions

Evidence from this study does not support a causal role of circulating serum urate levels in T2D, CHD, ischemic stroke, or heart failure. Lowering serum urate levels may not translate into risk reductions for cardiometabolic conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Uric acid is the end product of purine metabolism and circulates in the blood as the anion urate. Blood levels of uric acid are known to be causally associated with gout, as implicated by evidence from randomized clinical trials using urate lowering therapies.1 In 1923, Kylin initially described a constellation of metabolic disturbances that included hypertension, hyperglycermia, and elevated uric acid levels. Since then, circulating levels of serum uric acid have been shown positively correlated with a number of vascular risk factors including blood pressure, lipids, kidney function, and other metabolic traits.2 A number of prospective epidemiological studies have associated increased serum uric acid levels and elevated risks for type 2 diabetes (T2D),3 coronary heart disease (CHD),4–7 ischemic stroke,8,9 and heart failure.10,11

No large-scale intervention studies, however, exist that have evaluated urate-lowering therapies for metabolic and vascular outcomes. In the absence of such evidence, it remains unknown whether circulating uric acid is an independent causal factor for cardiometabolic conditions and whether lowering urate levels might be of therapeutic utility in these disorders.

Human genetic data can be used to directly test the hypothesis of causality between uric acid and clinical endpoints. In particular Mendelian randomization (MR) studies assess causal inference by using genetic alleles as unbiased proxies for circulating biomarkers.12 MR studies are based on the random assortment of genetic alleles during meiosis and can confer advantages similar to a randomized controlled trial by investigating the relationship between genetic alleles that are exclusively associated with a biomarker of interest and disease risk.13 Such an approach has been previously used to assess the causality of low- and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol,14 triglycerides,15 lipoprotein(a),16–17 fibrinogen,18 and C-reactive protein in CHD.19

The objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that serum urate levels are causally associated with cardiometabolic conditions by applying a MR study design. We have integrated information on genetic variants related to serum urate, 50 potential confounders, and risk of disease outcomes. In contrast to the previously published genetic reports on serum urate related genetic variants and disease risk,20–23 the current study investigates greater than 10 times more CHD cases and 3 times more T2D cases and examines for the first time risks of stroke and heart failure conferred by genetically raised serum urate levels. It also systematically evaluates pleiotropy, enabling reliable assessment of any possible moderate causal effect of serum urate levels on any of the four major cardiometabolic outcomes.

METHODS

Study Design

The study had three interrelated components. First, we selected single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that were previously discovered in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of serum urate levels. Second, we conducted genetic analyses in relation to a panel of 50 vascular and non-vascular risk factors and identified SNPs that did not exhibit pleiotropy (i.e., SNPs exclusively associated with circulating urate levels but not with other cardiometabolic traits that might confound our interpretation). For these analyses, we queried publicly available resources and genome-wide association data available from 18,828 subjects of the Pakistan Risk of Myocardial Infarction Study (PROMIS), a case-control study in urban Pakistan.24 Third, we used a genetic risk score comprised of SNPs exclusively associated with serum urate levels to evaluate the potential causal role of circulating urate levels in T2D, CHD, ischemic stroke, and heart failure through a MR approach.

Urate Genetic Variants and Assessment of Pleiotropy

All of the 28 urate SNPs included in the current analyses were in linkage equilibrium (r2 = 0, based on participants of European, South Asian and East Asian ancestries in HapMap-II and HapMap-III).25 Each SNP was evaluated for associations with 50 vascular and non-vascular traits in up to 18,828 South Asian individuals enrolled in PROMIS.24 Information from publicly available GWAS databases was also used to assess associations of these SNPs with blood pressure traits in up to 134,433 participants (Global BPgen Consortium),26 with major lipids in up to 100,000 participants (Global Lipids Genetics Consortium),27 with anthropometric traits in up to 183,727 participants (Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits; GIANT),28–30 and with glycemic traits in up to 46,368 non-diabetic participants (Meta-Analyses of Glucose and Insulin-related traits Consortium; MAGIC).31–34 Pleiotropy was declared at a nominal P-value of < 0.01. Only non-pleiotropic SNPs were used to construct a urate-specific genetic risk score. We employed additive linear regression models to interrogate the urate genetic risk score in association with a range of traits in PROMIS.

Association with Disease Outcomes

For each of the 28 SNPs, summary effect estimates in association with T2D, CHD, ischemic stroke and heart failure were obtained from various consortia, including DIAGRAM,35 CARDIoGRAM,36 C4D,36 METASTROKE,37 and CHARGE-Heart Failure studies.38 DIAGRAM data was downloaded from their website (http://diagram-consortium.org); whereas other data was acquired by contacting investigators within each consortia. We maximized study power by obtaining further data on participants that did not contribute to any of these consortia previously and increased sample size for CHD, ischemic stroke and heart failure by up-to 25% (eTable 1). Effect sizes and errors from consortia data and study-specific effect sizes and errors from additional studies (eTable-1) were combined via meta-analysis (inverse-variance fixed-effect model). In the final analyses, data was available on 26,488 T2D cases and 83,964 controls, 54,501 CHD cases and 68,275 controls; 14,779 ischemic stroke cases and 67,312 controls; and 4,553 heart failure cases and 19,985 controls. Effect estimates in association with prevalent gout were obtained from the Global Urate Genetics Consortium (GUGC) involving 3,151 gout cases and 68,350 controls.39 All participants were of self-reported European or South Asian ancestry. Individual studies within each consortium obtained written informed consent from participants and received approval from the relevant ethics board.

Statistical Analyses

All 28 SNPs used in the current analyses have been previously shown to be associated, at a P-value of < 5x10−8, with serum urate levels.39 The association of each SNP with each cardiometabolic outcome was evaluated with a fixed-effects inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis using beta(s) and standard error(s) obtained from consortia and studies listed in e-Table-1. SNPs found exclusively associated with serum urate levels were used in a genetic score as an instrument for MRanalyses.39,40 The impact of the urate genetic score on disease risk was calculated using methods described previously.41,42 Briefly, under the assumptions that SNPs are unlinked and the effects of each SNP are log-additive on levels of uric acid, using a MR framework,12,13 a causal effect (alpha-hat) between a biomarker and outcome can be estimated by:

where for all j SNPs, βj represents the estimated natural log odds effect of the j-th SNP on the endpoint of interest, sj represents the standard error on the log odds effect of the j-th SNP on the endpoint, and wj represents a weight for the SNP on the outcome. Each SNP was weighted using the reported estimated effect of the SNP on uric acid levels (in standard deviation units). Standard error for alpha-hat was calculated by taking the square root of the reciprocal of the denominator, as previously described.42 A simulation approach was used to estimate the power to identify or exclude causal effects of the urate genetic score on each tested outcome (eSupplement).43 All analyses were conducted in STATA, R, SNPTEST, or PLINK.

RESULTS

Assessment of Urate Variants for Pleiotropy

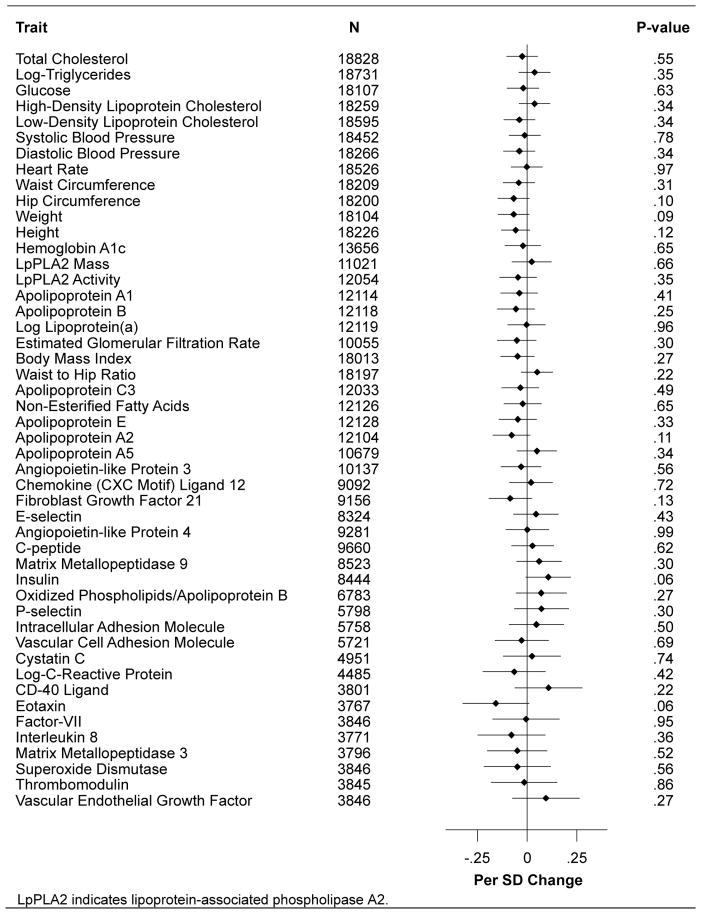

Of the 28 SNPs related to serum urate levels, 14 variants had pleiotropic associations at a P-value of < 0.01 with at least one vascular or non-vascular trait (eTables 2 and 3). The remaining 14 non-pleiotropic SNPs were used in a genetic score weighted for the reported urate effect estimate of each SNP. The weighted genetic risk score was not associated with any vascular or non-vascular trait at a P-value of < 0.01 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Association of Urate Genetic Score with Potential Confounders

Urate Genetic Variants and Disease Outcomes

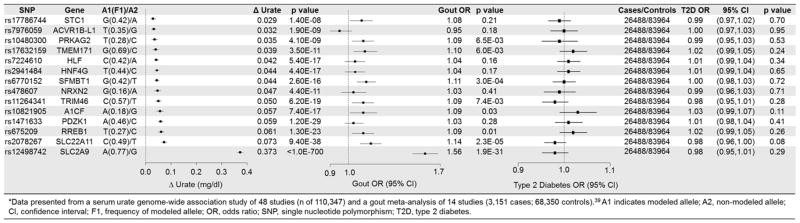

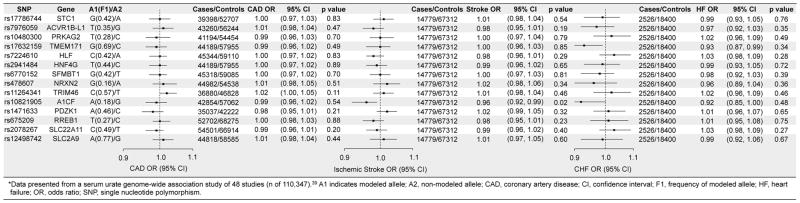

Of the 14 urate-specific SNPs, 9 variants were associated with increased risks of gout but none of the variants were associated with T2D, CHD, ischemic stroke, or heart failure at a P-value of <0.01 (Figures 2 and 3). Most notably, the SNP at the SLC2A9 locus, which was associated with the largest increases in serum urate level (0.37 mg/dl) and risk of gout (OR 1.56; 95% CI, 1.45–1.68; P-value = 1.9x10−31), was not associated with any of the cardiometabolic outcomes. Of the 14 pleiotropic SNPs, we found one SNP at the ATXN2 locus to be significantly associated with increased risk of CHD (OR 1.06; 95% CI, 1.03–1.08, P-value = 6.5 x 10−6) and ischemic stroke (OR 1.08; 95% CI, 1.04–1.11, P-value = 4.4 x 10−6) (eTable 5). The variant at the VEGFA locus was significantly associated with decreased risk of T2D (OR 0.93; 95% CI, 0.89–0.96, P-value = 1x10−4) but increased serum urate levels (eTable 4).

Figure 2.

Associations of Non-Pleiotropic Urate Variants with Serum Urate, Gout, and Type 2 Diabetes

Figure 3.

Associations of Non-Pleiotropic Urate Variants with Coronary Artery Disease, Ischemic Stroke, and Heart Failure

Urate Genetic Score and Disease Outcomes

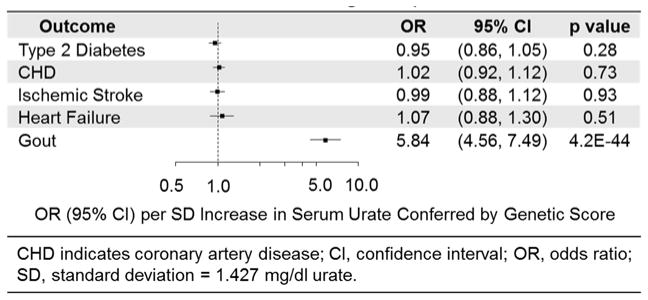

For a 1-SD increase in serum uric acid levels, the OR of gout conferred by genetic score was 5.84 (95% CI 4.56–7.49; p = 4.2x10−44), which was directionally consistent with the observed OR of 2.12 (95% CI, 1.90–2.33) for gout in epidemiological studies.44 However, a 1 SD increase in serum urate due to the genetic score had no relationship with T2D (OR 0.95; 95% CI, 0.86–1.05, p = 0.28), CHD (OR 1.02; 95% CI, 0.92–1.12; p = 0.73), ischemic stroke (OR 0.99; 95% CI, 0.88–1.12; p = 0.93), or heart failure (OR 1.07; 95% CI, 0.88–1.30; p = 0.51) (Figure 4). In further subsidiary analysis, a genetic risk score comprised of all 28 urate-related SNPs was not associated with all the four cardio-metabolic outcomes (eTable 6). A score based on the 14 urate-related variants with pleiotropic effects was also not associated with stroke or heart failure (eTable 7). However, this score was nominally associated with T2D, though in a direction opposite of epidemiological expectation, and weakly associated with CHD. We posit that these weak associations are explained by strong, confounding associations of these SNPs with blood pressure, cholesterol, trigylcerides, obesity, glucose, insulin and insulin resistance (eTable 3). These null associations are in contrast to data from observational epidemiological studies which have previously shown that equivalent increases in serum urate levels are associated with increased risks of T2D (OR 1.25; 95% CI, 1.13–1.37),3 CHD (OR 1.06; 95% CI, 1.03–1.09),4 ischemic stroke (OR 1.17: 95% CI 1.00–1.37),8 and heart failure(OR 1.19; 95% CI, 1.17–1.21).10 For a 1-SD change in serum urate levels due to genetic score, our study was statistically powered at >80% with a 5% alpha rate to assess ORs of 1.15 for T2D, 1.17 for ischemic stroke, 1.10 for CHD, and 1.24 for heart failure.

Figure 4.

Association of Genetically Raised Urate with Cardiometabolic Outcomes Using Multiple Genetic Variants

We conducted sensitivity analyses and investigated, in the same study population, the associations of the previously published urate related SNPs with serum urate levels and CHD risk. In the seven studies in which we conducted such analyses, we found highly significant associations for uric acid levels by the three risk scores that we have used in the main analyses above (eFigure-1a) whereas no association was observed between any of the risk score investigated and CHD risk in the same studies (eFigure1b). We further restricted our analyses to three studies in which we investigated the association of (i) serum urate levels with CHD risk, (ii) SNPs with serum urate levels and (iii) SNPs with CHD risk. While we found highly significant associations between circulating serum urate levels and CHD risk (eFigure2a) and highly significant associations between SNPs and serum urate levels (eFigure2b), no association was observed for any of three urate-related genetic risk scores with CHD risk (eFigure2c). These sensitivity analyses provide further validation to “two-stage” MR experiment employed above. Further, in analyses stratified by ethnicity, similar null results were obtained for participants of European or South Asian origin (eTable8a–c).

Discussion

Contrary to epidemiological studies in humans where higher serum urate levels correlate with increased risk of cardio-metabolic outcomes, the MR analyses reported here provide no evidence of causal associations between circulating urate levels and risks of T2D, CHD, ischemic stroke or heart failure. First, we analyzed all SNPs associated with circulating urate levels across a range of vascular and non-vascular traits to assess pleiotropy. We identified 14 SNPs exclusively associated with serum urate levels. Second, we found that a genetic score combining these non-pleiotropic variants exclusively increased uric acid levels and increased the risk of gout. Third, we have shown that none of the urate-specific SNPs individually or combined as a genetic score associated with any cardio-metabolic outcome. Fourth, a genetic risk score comprised of all the 28 SNPs known to regulate serum urate levels was not associated with any cardio-metabolic outcome.

The current study raises doubts about the etiological relevance of serum uric acid in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases as suggested by prior epidemiological and model systems studies,3–11,45 which may have observed increased uric acid levels to associate with higher risk of cardio-metabolic diseases due to residual confounding or reverse causality. Moreover, no large scale randomized control trials have been conducted using targeted interventions to lower serum urate levels (e.g., xanthine-oxidase inhibition inhibition) for the primary prevention of cardio-metabolic endpoints. There is an on-going trial, Exact-HF, that is evaluating the role of xanthine-oxidase inhibitors in patients with heart failure.46 Evidence from prior studies have suggested a role for urate lowering therapies in lowering blood pressure in adolescents with hyperuricemia, ameliorating exercise capacity in patients with chronic stable angina, improving endothelial function in patients with heart failure and making other biochemical parameters more favorable in patients with stable disease.47–49 Such evidence, however, was generated through studies conducted in populations with prevalent and stable disease and does not assess the association of urate reduction with primary cardio-metabolic events (i.e., stroke, CHD, diabetes or heart failure). Moreover, these prior studies do not address the etiological relevance of urate reduction in the prevention of primary cardio-metabolic events in healthy participants. In contrast, findings from this report suggest that uric acid lowering may not succeed in primary prevention of metabolic and vascular events, which is also consistent with a recent study that showed initiation of xanthine oxide inhibitors in patients with gout was not associated with a change in cardiovascular disease risk.50

Our findings are consistent with a prior report that evaluated variation at the SLC2A9 gene in association with ischemic heart disease and found no evidence of an association between genetically lowered uric acid and CHD or blood pressure.21 The current study extends these prior findings by evaluating all variants associated with uric acid systematically, exploring pleiotropy for all uric-acid related variants, investigating other cardiometabolic outcomes (i.e., type-2 diabetes, stroke and heart failure) and assessing greater than 7-fold more CHD cases (54501 cases in the current report compared to 7172 in the prior report). It thus provides an analysis adequately powered to assess urate variants and genetic scores known to have modest effects on urate levels.

We observed that one serum urate SNP in the ATXN2 gene, which was pleiotropic for major lipid, glycemic and anthropometric traits (and thus excluded from our score-based MR analysis), appeared to be associated with risks of CHD and ischemic stroke at nominal levels of significance. This SNP is located in a high-frequency (~40%) long-range (1.6 Mb) haplotype, previously described to be associated with a range of other traits including type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, and elevated platelet counts. This haplotype is speculated to have arisen from a selective sweep specific to Europeans around 3,400 years ago when high-density human settlements were expanding in that region of the world.51 In analyses restricted to participants of South Asian ancestry, we did not find this variant to be associated with major lipids in 37,000 participants or with risks of CHD (9,000 cases and 9,000 controls) and ischemic stroke (3,500 cases and 5,000 controls). Because of the high pleiotropic nature of this locus and specificity to populations of European ancestry, it is unlikely that the ATXN2 locus leads to CHD by increasing serum urate levels.

Potential limitations of this study should be considered. First, while analyses on heart failure in the current study were underpowered (eTable 9), the concordance of the null findings observed for all cardio-metabolic outcomes tend to suggest a lack of a major etiological role of serum urate levels in heart failure. Second, we evaluated only 50 traits to assess pleiotropy for uric acid SNPs and did not conduct measurements for all possible biological traits; however we conducted analyses using both single SNPs and a genetic risk score in association with cardio-metabolic outcomes. Importantly, we also conducted analyses for a variant, rs12498742, that imparts the strongest effect on uric acid levels (eTable 10) and is located in an intron of the SLC2A9 gene that encodes for a glucose and urate transporter in the kidney, hence providing biological plausibility to our hypothesis. We did not find this variant to be associated with any other trait apart from circulating urate levels; hence enabling MR analyses using this variant only. We did not find rs12498742 to be associated with any cardio-metabolic outcome despite the fact that MR analyses with this variant were sufficiently powered (eTable 9). Third, non-pleiotropic variants in addition to the SLC2A9 variant explained only 15.3% of the variance in the serum urate levels (eTable 10). However, none of them were associated with any of the investigated cardiometabolic endpoints in our large-scale analyses, which casts further doubt on serum urate as a causal factor. Fourth, as suggested by our power calculations (eTable-9), while we were able to exclude effects imparted by a one SD change in serum urate levels on disease risk which are weak to modest and consistent with prior epidemiological studies3–11 (eTable-9); our analyses may not have detected very weak disease risk estimates (e.g., OR for CHD < 1.10). Fifth, while our assessment of causality was limited to SNPs that are observed to be non-pleiotropic, it can be argued that the loci that do exhibit pleiotropy can mediate the disease. We ruled out the later possibility by demonstrating that risk-scores comprised of all 28 SNPs or 14 pleiotropic SNPs were not associated with any cardiometabolic outcomes. Sixth, while we had access to only summary level data which prevented adjustment for factors acting as potential mediators between genotypes and disease risk; MR analyses on summary level data have been shown to achieve results similar to the methods that have used individual participant data.14–19 Moreover, analyses with gout provided a positive control and reinforced the findings observed for other outcomes.

In summary, our MR analyses do not support a causal role of circulating serum urate concentrations in cardiometabolic conditions. Our results suggest that lowering serum urate levels may not translate into risk reductions for T2D, CHD, ischemic stroke, or heart failure events.

Supplementary Material

Message and Clinical Context.

Through a Mendelian Randomization experiment, we have demonstrated that while serum urate levels are causally relevant to gout; increased serum urate levels have no causal relevance in coronary heart disease, type-2 diabetes, ischemic stroke or heart failure. These findings are in contrast to prior observational studies and decrease the likelihood of any beneficial effects on the above cardiometabolic conditions by lowering serum urate levels through pharmacological agents.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the CARDIoGRAM consortium, the C4D consortium, the CHARGE Heart Failure Consortium, the GUGC Consortium and the International Stroke Genetics consortium for contributing data. Dr. Saleheen has received funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Fogarty International, the Wellcome Trust, the British Heart Foundation and Pfizer. Dr. Voight was supported by a Fellowship from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (BR2012-087) and has received funding from the American Heart Association (13SDG14330006), and the W.W. Smith Charitable Trust (H1201). Acknowledgements by studies that contributed data to the analyses are as follows:

PROMIS and RACE. Dr. Saleheen is the PI of the PROMIS and RACE studies. Genotyping in PROMIS was funded by the Wellcome Trust, UK and Pfizer. Biomarker assays in PROMIS have been funded through grants awarded by the NIH (RC2HL101834 and RC1TW008485) and the Fogarty International (RC1TW008485). The RACE study has been funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders (R21NS064908), the Fogarty International (R21NS064908) and the Center for Non-Communicable Diseases, Karachi, Pakistan.

We also acknowledge the contributions made by the following: Mohammad Zeeshan Ozair, Usman Ahmed, Abdul Hakeem, Hamza Khalid, Kamran Shahid, Fahad Shuja, Ali Kazmi, Mustafa Qadir Hameed, Naeem Khan, Sadiq Khan, Ayaz Ali, Madad Ali, Saeed Ahmed, Muhammad Waqar Khan, Muhammad Razaq Khan, Abdul Ghafoor, Mir Alam, Riazuddin, Muhammad Irshad Javed, Abdul Ghaffar, Tanveer Baig Mirza, Muhammad Shahid, Jabir Furqan, Muhammad Iqbal Abbasi, Tanveer Abbas, Rana Zulfiqar, Muhammad Wajid, Irfan Ali, Muhammad Ikhlaq, Danish Sheikh and Muhammad Imran.

Studies participating in the INTERSTROKE consortium

The MGH Genes Affecting Stroke Risk and Outcome Study (MGH-GASROS). GASROS was supported by The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U01 NS069208), the American Heart Association/Bugher Foundation Centers for Stroke Prevention Research 0775010N, the National Institutes of Health and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s STAMPEED genomics research program (R01 HL087676) and a grant from the National Center for Research Resources. The Broad Institute Center for Genotyping and Analysis is supported by grant U54 RR020278 from the National Center for Research resources.

CHARGE –Stroke data. This work was supported by the dedication of the Framingham Heart Study participants, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute’s Framingham Heart Study (Contract No. N01-HC-25195) and by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS17950), the National Institute of Aging (AG033193), the and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Association (HL93029, U01HL 096917). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

CEDIR (Cerebrovascular Diseases Registry), Milano, Italy. We would like to acknowledge: Eugenio A. Parati and Emilio Ciusani, from Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta” of Milan, contributed to collection and genotyping of cases within CEDIR (Cerebrovascular Diseases Registry), funded by Annual Research Funding of the Italian Ministry of Health (Grant Numbers: RC 2007/LR6, RC 2008/LR6; RC 2009/LR8; RC 2010/LR8). Simona Barlera and Maria Grazia Franzosi, from Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche “Mario Negri” of Milan, contributed to collection and genotyping of the PROCARDIS controls, funded by FP6 LSHM-CT-2007-037273.

BRAINS. Pankaj Sharma is supported by a Dept of Health (UK) Senior Fellowship. BRAINS is supported by grants from British Council (UK-India Education and Research Initiative), Henry Smith Charity and Qatar National Research Fund.

CHARGE Heart failure consortium

At the time of preparation of the manuscript, Janine F Felix was working in Erasmus AGE, a center for aging research across the life course funded by Nestlé Nutrition (Nestec Ltd.), Metagenics Inc. and AXA. These funding sources had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Abbreviations used

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- T2D

type-2 diabetes

- MR

Mendelian Randomization

- SNPs

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- PROMIS

Pakistan Risk of Myocardial Infarction Study

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

Footnotes

Authors Disclosures:

None

References

- 1.Tayar JH, Lopez-Olivo MA, Suarez-Almazor ME. Febuxostat for treating chronic gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD008653. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008653.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feig DI, Kang DH, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2008 doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kodama S, Saito K, Yachi Y, et al. Association between serum uric acid and development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(9):1737–1742. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wheeler JG, Juzwishin KD, Eiriksdottir G, Gudnason V, Danesh J. Serum uric acid and coronary heart disease in 9,458 incident cases and 155,084 controls: Prospective study and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2005;2(3):e76. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SY, Guevara JP, Kim KM, Choi HK, Heitjan DF, Albert DA. Hyperuricemia and coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62(2):170–180. doi: 10.1002/acr.20065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chuang SY, Chen JH, Yeh WT, Wu CC, Pan WH. Hyperuricemia and increased risk of ischemic heart disease in a large chinese cohort. Int J Cardiol. 2012;154(3):316–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kivity S, Kopel E, Maor E, et al. Association of serum uric acid and cardiovascular disease in healthy adults. Am J Cardiol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hozawa A, Folsom AR, Ibrahim H, Nieto FJ, Rosamond WD, Shahar E. Serum uric acid and risk of ischemic stroke: The ARIC study. Atherosclerosis. 2006;187(2):401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SY, Guevara JP, Kim KM, Choi HK, Heitjan DF, Albert DA. Hyperuricemia and risk of stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(7):885–892. doi: 10.1002/art.24612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holme I, Aastveit AH, Hammar N, Jungner I, Walldius G. Uric acid and risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and congestive heart failure in 417,734 men and women in the apolipoprotein MOrtality RISk study (AMORIS) J Intern Med. 2009;266(6):558–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishnan E. Hyperuricemia and incident heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2(6):556–562. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.797662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sterne JA, Timpson N, Davey Smith G. Mendelian randomization: Using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat Med. 2008;27(8):1133–1163. doi: 10.1002/sim.3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. What can Mendelian randomisation tell us about modifiable behavioural and environmental exposures? BMJ. 2005;330(7499):1076–1079. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7499.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voight BF, Peloso GM, Orho-Melander M, et al. Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: A Mendelian randomisation study. Lancet. 2012;380(9841):572–580. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60312-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Triglyceride Coronary Disease Genetics Consortium and Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Sarwar N, Sandhu MS, et al. Triglyceride-mediated pathways and coronary disease: Collaborative analysis of 101 studies. Lancet. 2010;375(9726):1634–1639. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60545-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke R, Peden JF, Hopewell JC, et al. Genetic variants associated with lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(26):2518–2528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamstrup PR, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Steffensen R, Nordestgaard BG. Genetically elevated lipoprotein(a) and increased risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2009;301(22):2331–2339. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ken-Dror G, Humphries SE, Kumari M, Kivimaki M, Drenos F. A genetic instrument for Mendelian randomization of fibrinogen. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012;27(4):267–279. doi: 10.1007/s10654-012-9666-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elliott P, Chambers JC, Zhang W, et al. Genetic loci associated with C-reactive protein levels and risk of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2009;302(1):37–48. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfister R, Barnes D, Luben R, et al. No evidence for a causal link between uric acid and type 2 diabetes: A Mendelian randomisation approach. Diabetologia. 2011;54(10):2561–2569. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer TM, Nordestgaard BG, Benn M, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Davey Smith G, Lawlor DA, Timpson NJ. Association of plasma uric acid with ischaemic heart disease and blood pressure: mendelian randomisation analysis of two large cohorts. BMJ. 2013 Jul 18;347:f4262. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stark K, Reinhard W, Grassl M, et al. Common polymorphisms influencing serum uric acid levels contribute to susceptibility to gout, but not to coronary artery disease. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Q, Kottgen A, Dehghan A, et al. Multiple genetic loci influence serum urate levels and their relationship with gout and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3(6):523–530. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.934455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saleheen D, Zaidi M, Rasheed A, et al. The Pakistan Risk of Myocardial Infarction Study: A resource for the study of genetic, lifestyle and other determinants of myocardial infarction in south asia. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24(6):329–338. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9334-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Abecasis GR, Altshuler D, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467(7319):1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newton-Cheh C, Johnson T, Gateva V, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight loci associated with blood pressure. Nat Genet. 2009;41(6):666–676. doi: 10.1038/ng.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466(7307):707–713. doi: 10.1038/nature09270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heid IM, Jackson AU, Randall JC, et al. Meta-analysis identifies 13 new loci associated with waist-hip ratio and reveals sexual dimorphism in the genetic basis of fat distribution. Nat Genet. 2010;42(11):949–960. doi: 10.1038/ng.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lango Allen H, Estrada K, Lettre G, et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010;467(7317):832–838. doi: 10.1038/nature09410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Speliotes EK, Willer CJ, Berndt SI, et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat Genet. 2010;42(11):937–948. doi: 10.1038/ng.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dupuis J, Langenberg C, Prokopenko I, et al. New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet. 2010;42(2):105–116. doi: 10.1038/ng.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saxena R, Hivert MF, Langenberg C, et al. Genetic variation in GIPR influences the glucose and insulin responses to an oral glucose challenge. Nat Genet. 2010;42(2):142–148. doi: 10.1038/ng.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soranzo N, Sanna S, Wheeler E, et al. Common variants at 10 genomic loci influence hemoglobin A(1)(C) levels via glycemic and nonglycemic pathways. Diabetes. 2010;59(12):3229–3239. doi: 10.2337/db10-0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strawbridge RJ, Dupuis J, Prokopenko I, et al. Genome-wide association identifies nine common variants associated with fasting proinsulin levels and provides new insights into the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2011;60(10):2624–2634. doi: 10.2337/db11-0415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris AP, Voight BF, Teslovich TM, et al. Large-scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2012;44(9):981–990. doi: 10.1038/ng.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The CARDIoGRAMplusC4D Consortium. Deloukas P, Kanoni S, et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies new risk loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2012;45(1):25–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Traylor M, Farrall M, Holliday EG, et al. Genetic risk factors for ischaemic stroke and its subtypes (the METASTROKE collaboration): A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(11):951–962. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70234-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith NL, Felix JF, Morrison AC, et al. Association of genome-wide variation with the risk of incident heart failure in adults of european and african ancestry: A prospective meta-analysis from the cohorts for heart and aging research in genomic epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3(3):256–266. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.895763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kottgen A, Albrecht E, Teumer A, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 18 new loci associated with serum urate concentrations. Nat Genet. 2013;45(2):145–154. doi: 10.1038/ng.2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palmer TM, Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, et al. Using multiple genetic variants as instrumental variables for modifiable risk factors. Stat Methods Med Res. 2012;21(3):223–242. doi: 10.1177/0962280210394459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson T. Efficient calculation for multi-SNP genetic risk scores. Presented at: American Society of Human Genetics Annual Meeting; November 6–10, 2012; San Francisco, CA. http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gtx/vignettes/ashg2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dastani Z, Hivert MF, Timpson N, et al. Novel loci for adiponectin levels and their influence on type 2 diabetes and metabolic traits: A multi-ethnic meta-analysis of 45,891 individuals. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(3):e1002607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Voight BF. MR_predictor: A simulation engine for mendelian randomization studies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(23):3432–3434. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhole V, de Vera M, Rahman MM, Krishnan E, Choi H. Epidemiology of gout in women: Fifty-two-year followup of a prospective cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(4):1069–1076. doi: 10.1002/art.27338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dziuba J, Alperin P, Racketa J, et al. Modeling effects of SGLT-2 inhibitor dapagliflozin treatment versus standard diabetes therapy on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(7):628–635. doi: 10.1111/dom.12261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Givertz MM, Mann DL, Lee KL, et al. Xanthine oxidase inhibition for hyperuricemic heart failure patients: Design and rationale of the EXACT-HF study. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(4):862–868. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feig DI, Soletsky B, Johnson RJ. Effect of allopurinol on blood pressure of adolescents with newly diagnosed essential hypertension: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008 Aug 27;300(8):924–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.George J, Carr E, Davies J, Belch JJ, Struthers A. High-dose allopurinol improves endothelial function by profoundly reducing vascular oxidative stress and not by lowering uric acid. Circulation. 2006 Dec 5;114(23):2508–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.651117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kelkar A, Kuo A, Frishman WH. Allopurinol as a cardiovascular drug. Cardiol Rev. 2011 Nov-Dec;19(6):265–71. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e318229a908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim SC, Schneeweiss S, Choudhry N, Liu J, Glynn RJ, Solomon DH. Effects of xanthine oxidase inhibitors on cardiovascular disease in patients with gout: A cohort study. Am J Med. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soranzo N, Sanna S, Wheeler E, et al. Common variants at 10 genomic loci influence hemoglobin A(1)(C) levels via glycemic and nonglycemic pathways. Diabetes. 2010;59(12):3229–3239. doi: 10.2337/db10-0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.