Abstract

Objective

Theory use may enhance effectiveness of behavioral interventions, yet critics question whether theory-based interventions have been sufficiently scrutinized. This study applied a framework to evaluate theory use in physical activity interventions for breast cancer survivors. The aims were to (1) evaluate theory application intensity and (2) assess the association between extensiveness of theory use and intervention effectiveness.

Methods

Studies were previously identified through a systematic search, including only randomized controlled trials published from 2005 to 2013, that addressed physical activity behavior change and studied survivors who were <5 years posttreatment. Eight theory items from Michie and Prestwich’s coding framework were selected to calculate theory intensity scores. Studies were classified into three subgroups based on extensiveness of theory use (Level 1 = sparse; Level 2 = moderate; and Level 3 = extensive).

Results

Fourteen randomized controlled trials met search criteria. Most trials used the transtheoretical model (n = 5) or social cognitive theory (n = 3). For extensiveness of theory use, 5 studies were classified as Level 1, 4 as Level 2, and 5 as Level 3. Studies in the extensive group (Level 3) had the largest overall effect size (g = 0.76). Effects were more modest in Level 1 and 2 groups with overall effect sizes of g = 0.28 and g = 0.36, respectively.

Conclusions

Theory use is often viewed as essential to behavior change, but theory application varies widely. In this study, there was some evidence to suggest that extensiveness of theory use enhanced intervention effectiveness. However, there is more to learn about how theory can improve interventions for breast cancer survivors.

Keywords: behavioral theories, breast cancer, cancer prevention and screening, chronic disease management, health behavior, physical activity/exercise, research design

Using behavior theory has been suggested as a way to improve the effectiveness of behavior change interventions (Davis, Campbell, Hildon, Hobbs, & Michie, 2014; Fishbein & Yzer, 2003; Glanz & Bishop, 2010). Researchers propose that behavior theory may potentially improve a behavior change intervention by linking relevant causal factors of the behavior to appropriate change methods (Bartholomew & Mullen, 2011). Assessing theory integration throughout the design, implementation, and evaluation of interventions may also provide valuable insight on how these components contribute to effectiveness in changing behavioral outcomes (Lippke & Jochen, 2008; Rothman, 2004). However, in practice, theory use in program planning varies widely, making it difficult to assess the intensity of theory application and its impact on behavior change (Wallace, Brown, & Hilton, 2014).

Some critics suggest that more differentiation is needed between theory-informed interventions (i.e., those that vaguely describe theory use) and theory-driven interventions (i.e., those that integrate theory throughout program planning, design, and evaluation; Michie & Abraham, 2004). In a systematic review of nearly 200 health behavior change studies, Painter, Borba, Hynes, Mays, and Glanz (2008) found that only about one third of studies described using theory to inform interventions, and a much smaller proportion provided explicit detail that would suggest a more integrated approach to theory use. Other recent reviews on physical activity and dietary behaviors found similar discrepancies in reporting of theory use and offered conflicting interpretations of how theory application contributed to intervention effectiveness in those studies (Prestwich et al., 2013; Taylor, Conner, & Lawton, 2012). This incongruence highlights the ongoing need to critically assess how theory is applied in intervention development and to further assess the role of extensiveness of theory use on intervention effectiveness. This is a particular need in the field of survivorship research, in which breast cancer survivors are the frequent focus of lifestyle interventions yet there is little consensus on optimal theories and theory integration techniques to change physical activity behaviors in this population (Pinto & Floyd, 2008; Short, James, Stacey, & Plotnikoff, 2013).

Physical activity in posttreatment breast cancer survivors is a growing area of research interest. It offers unique benefits to breast cancer survivors after completion of primary treatment, including improving physical function, mitigating cancer or cancer treatment side effects (such as lymphedema), enhancing quality of life (McNeely et al., 2006; Prinsen et al., 2013; Sabiston & Brunet, 2012), and potentially reducing recurrence risk (Ballard-Barbash et al., 2012). Currently, breast cancer survivors are advised to achieve at least 120 to 150 minutes per week of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity to meet health recommendations (Rock et al., 2012). However, it has been estimated that only about 10% of breast cancer survivors are meeting these recommendations (Smith & Chagpar, 2010). Identifying strategies to promote physical activity, then, may both influence behavior and present an opportunity to enhance these benefits for breast cancer survivors, especially as they transition from completion of active treatment to long-term recovery (Lemanne, Cassileth, & Gubili, 2013).

This report explores theory application in a set of behavior change interventions specifically designed to increase physical activity in posttreatment breast cancer survivors. The impetus for this report stems from a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis of physical activity interventions in posttreatment breast cancer survivors in which we found that most interventions were only moderately effective in producing short-term lifestyle changes (Bluethmann, Vernon, Gabriel, Murphy, & Bartholomew, 2015). However, this initial review did not separately assess theory application and intervention effectiveness, specifically in terms of theory selection, intervention components, measures, and reporting of results, providing an opportunity to make contributions to the literature on optimal strategies for health behavior theory use with breast cancer survivors. In this report, we evaluate the extent to which theory was applied and to describe theory application in relation to the effect size estimates observed in those studies. The specific aims of this report are to (1) evaluate the intensity of theory application in behavior change interventions for breast cancer survivors and (2) assess the possible association between extensiveness of theory use and intervention effectiveness.

Method

Search Strategy

Studies used in this analysis were identified through a systematic search strategy and review that are reported in detail elsewhere (Bluethmann et al., 2015). The first author worked with a trained public health librarian and followed Preferred Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & the PRISMA Group, 2009) to search four databases: Medline (via Ovid; 1948 to September Week 2 2013; In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations; searched September 19, 2013); PubMed (National Library of Medicine; searched September 20, 2013); PsycINFO (via Ovid; 2002 to September Week 4 2013; searched October 1, 2013); and CINAHL Plus with Full Text (via Ebsco; 2001 to present; searched October 4, 2013).

All eligible studies met the following criteria: (1) published in English in a peer-reviewed journal between January 2005 and October 2013, (2) used a randomized controlled trial or quasi-experimental design with at least one comparison group, (3) studied breast cancer survivors who were 5 years or less from completion of active cancer treatment (i.e., breast cancer survivors transitioning to long-term recovery), (4) evaluated a behavior intervention targeting physical activity, and (5) reported physical activity behavior change outcomes. As previously reported, studies conducted after 2005 were selected to inform the contributions of behavior change interventions following the release of the Institute on Medicine guidelines for Survivorship Care (Bluethmann et al., 2015).

Procedures for Coding and Classification

For this report, major components of all the interventions were summarized using abstracted intervention descriptors, including physical activity type, setting, mode of delivery, and identification of a primary theoretical framework. Next, we compared the intervention narrative in each study with a list of standardized definitions of theoretically derived behavior change techniques (Abraham & Michie, 2008) to characterize use of theoretical methods.

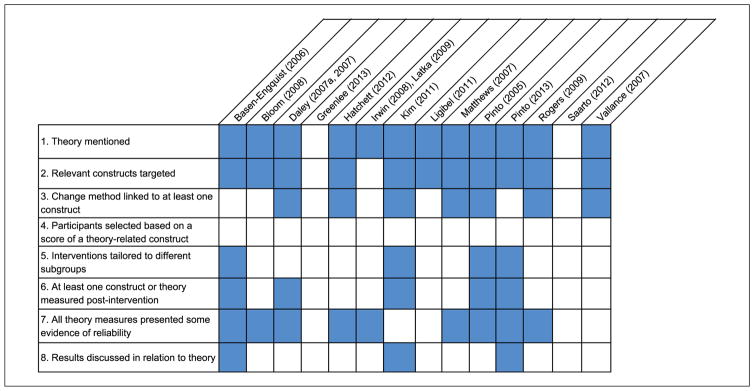

Theory application was assessed using a modified version of a behavior theory coding framework (Michie & Prestwich, 2010). The authors reviewed the six categories in the original framework, which includes broad considerations, such as identification of a theory and constructs, as well as specific methods related to theory measurement and evaluation in the intervention design. Eight items were then selected across categories that the authors felt could assess the intensity of theory application (from theory identification through evaluation of its use) and be fairly assessed as present or absent based on published details. The eight items were (1) theory was mentioned, (2) relevant constructs were targeted, (3) each intervention technique (i.e., change method) was explicitly linked to at least one theoretical construct, (4) participants were selected/screened based on prespecified criteria (e.g., a construct or predictor), (5) interventions were tailored for different subgroups, (6) at least one construct or theory mentioned in relation to the intervention was measured postintervention, (7) all measures of theory were presented with some evidence of their reliability, and (8) the results were discussed in relation to the theory. Additional items that fell outside of our focus on theory application within intervention development and evaluation, such as evaluation of how the study results might be used to further refine theories, were not considered.

Two independent coders applied these items to all studies in the analysis, and then calculated a theory intensity score (n/8), which was used to describe each study by extent of theory use. The coders discussed disagreements (occurred in less than 5% of items) and reached consensus on presence or absence of each item. Studies that satisfied 3 or fewer items were classified as Level 1 for theory use (Sparse Use of Theory). Studies that fulfilled 4 to 5 items were classified as Level 2 (Moderate Use of Theory). All other studies (those that satisfied 6 or more items) were considered Level 3 (Extensive Use of Theory). All authors agreed with the final coding and classification scheme.

Analysis

To assess the potential role of theory in enhancing intervention effectiveness, an exploratory subgroup analysis was performed based on the level of theory use assigned to the studies (i.e., Level 1, Level 2, or Level 3). This analysis complements previous effect size estimates from a random effects meta-analysis conducted with the same group of studies (Bluethmann et al., 2015). Meta-analysis parameters were calculated using the same process in the “metan” function in Stata 13.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX), comparing pooled effects on physical activity behavior using standardized mean differences.

Results

Fourteen randomized controlled trials met the search criteria. Descriptions of the intervention and theoretical methods are provided in Table 1. The most commonly used theories were the transtheoretical model (TTM; Prochaska & Velicer, 1997; n = 6) and social cognitive theory (Bandura, 2001; n = 4). Many of the physical activity studies citing the TTM as their primary theoretical framework used stage-matching as a way to tailor interventions to the readiness of participants to change their behavior. Other commonly mentioned theory-related behavior change methods were goal setting, social support, monitoring, feedback, modeling, and problem solving.

Table 1.

Summary of Interventions and Theory Use Descriptors.

| Study | Year (s) trial conducteda | Primary intervention components | Primary theoretical frameworkb | Theoretical/behavior change methods | Intensity score for theory use (n/8)c | Extent of theory used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basen-Engquist et al. (2006) | 2003–2004 | Workshops, group exercise, walking | TTM | Self-reevaluation, monitoring, rehearsal, general information, goal setting, general problem-solving | 6 | Level 3 |

| Bloom, Stewart, D’Onofrio, Luce, and Banks (2008) | NR | Workshops, group exercise | Social support | General information, instruction, rehearsal, goal setting, discussion | 3 | Level 1 |

| Daley et al. (2007a) | 2005 | Counseling (in person), group exercise | TTM | Instruction, rehearsal, goal setting, goal review, relapse prevention, monitoring, feedback, nonspecific social support | 5 | Level 3 |

| Kim et al. (2011) | NR | Counseling (by phone), walking | TTM | Prompt, tailoring, personalized message, individualization, general information, coping, feedback, goal setting, goal review, monitoring | 6 | Level 3 |

| Greenlee et al. (2013) | 2007–2008 | Counseling (in person and by phone), walking or similar | NR | — | 0 | Level 1 |

| Hatchett, Hallam, and Ford (2013) | NR | Counseling (by e-mail), any exercise | SCT | Goal, goal review, relapse prevention, feedback, general information, monitoring, prompt, instruction | 4 | Level 2 |

| Irwin et al. (2008a); Latka et al. (2009) | 2006 | Counseling (in group), group exercise, walking | TTM | Goal setting, instruction, graded tasks, feedback, general problem solving, general information, monitoring, prompt | 2 | Level 1 |

| Ligibel et al. (2011) | 2009 | Counseling (by phone), walking | SCT | Goal, goal review, relapse prevention, feedback, general information, monitoring, prompt, instruction | 4 | Level 2 |

| Matthews et al. (2007) | NR | Counseling (in person/by phone), walking | SCT | Goal, general information, goal review, feedback, general problem solving, planning coping, nonspecific social support, monitoring, prompt | 4 | Level 2 |

| Pinto, Frierson, et al. (2005a); Pinto, Rabin, et al. (2008); Pinto, Rabin, & Dunsinger (2009) | NR | Counseling (by phone/in person), walking | TTM | Instruction, monitoring, general problem solving, feedback, tailoring, personalized message, goal, goal review, planning coping, prompt, general information, graded tasks, individualization | 6 | Level 3 |

| Pinto, Papandonatos, and Goldstein (2013) | NR | Counseling (doctor/and by phone), walking | TTM | Instruction, monitoring, general problem solving, feedback, tailoring, personalized message, goal review, planning coping, prompt, general information, graded tasks, individualization | 6 | Level 3 |

| Rogers et al. (2009) | 2007 | Counseling (group and individual), group exercise, walking | SCT | Modeling, nonspecific social support, time management, stress management, general problem solving, instruction, goal review, monitoring, social comparison | 4 | Level 2 |

| Nikander et al. (2007), Penttinen et al. (2009), Saarto et al. (2012a) | 2005–2008 | Counseling (in person), group exercise, walking | NR | — | 0 | Level 1 |

| Vallance, Courneya, Plotnikoff, and Mackey (2008); Vallance, Courneya, Plotnikoff, Yasui, et al. (2007a); Vallance, Courneya, Plotnikoff, Dinu, et al. (2008) | 2006 | PA guidebook | TPB | General information, monitoring, prompt, goal review | 3 | Level 1 |

Where not explicitly stated, year(s) of trials were inferred by reported dates of recruitment completion. Where information not reported, dates were listed as “not reported” (NR).

Theory abbreviations are as follows: TTM = transtheoretical model; SCT = social cognitive theory; TPB = theory of planned behavior. Interventions in which a theoretical framework was missing were listed as “not reported” (NR).

Quality score based on number of reported items in modified list. See Method section for complete list.

Extensiveness of theory use was categorized as Level 1 (Sparse Use of Theory), Level 2 (Moderate Use of Theory) and Level 3 (Extensive Use of Theory). See Method section for details.

Applying the defined criteria, the intensity of theory application varied across the studies. A depiction of how these theory indicators were distributed across the studies reviewed is provided in Figure 1. The overall mean intensity score was 3.78 out of 8 items. The range of intensity scores was 0 (Greenlee et al., 2013; Saarto et al., 2012) to 6 (Basen-Engquist et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2011; Pinto et al., 2013; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Theory intensity scores by study.

Based on the previously described categories for extensiveness of theory use, five studies were classified as Level 1 (Bloom et al., 2008; Greenlee et al., 2013; Irwin et al., 2008; Saarto et al., 2012; Vallance et al., 2007), four as Level 2 (Hatchett et al., 2013; Ligibel et al., 2011; Matthews et al., 2007; Rogers et al., 2009), and five as Level 3 (Basen-Engquist et al., 2006; Daley et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2011; Pinto et al., 2005; Pinto et al., 2013). The mean intensity scores by category of theory use were 1.6 (Level 1), 4 (Level 2), and 6 (Level 3).

An exploratory subgroup analysis was used to assess the extent of theory use relative to intervention effectiveness. Comparing the three categories of theory use, the Level 3 studies (Extensive Theory Use) had the largest overall effect size (Hedge’s g = 0.76) compared with the other levels (Table 2). The studies in the Levels 1 and 2 groups had overall effect sizes of Hedge’s g = 0.28 and Hedge’s g = 0.36, respectively, conveying more modest differences between these two groups in terms of theory use.

Table 2.

Results of Sub-group Analysis by Extensiveness of Theory Use.

| Study (year) | SMD (g)a | 95% CI | % Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extensive use of theory | |||

| Basen-Engquist et al. (2006) | 0.09 | [−0.42, 0.59] | 20.00 |

| Daley et al. (2007) | 1.85 | [1.14, 2.55] | 16.23 |

| Kim et al. (2011) | 0.64 | [0.041, 1.24] | 18.23 |

| Pinto et al. (2005) | 0.90 | [0.46, 1.35] | 21.28 |

| Pinto et al. (2013) | 0.53 | [0.24, 0.82] | 24.15 |

| Pooled effect size | 0.76 | [0.31, 1.21] | 100 |

| Moderate Use of Theory | |||

| Hatchett et al. (2013) | 0.75 | [0.28, 1.22] | 27.27 |

| Ligibel et al. (2011) | −0.02 | [−0.41, 0.37] | 30.32 |

| Matthews et al. (2007) | 0.74 | [0.05, 1.42] | 20.00 |

| Rogers et al. (2009) | 0.07 | [−0.55, 0.68] | 22.37 |

| Pooled effect size | 0.36 | [−0.074, 0.8] | 100 |

| Sparse use of theory | |||

| Bloom et al. (2008) | 0.23 | [0.014, 0.45] | 25.12 |

| Greenlee et al. (2013) | 0.16 | [−0.472, 0.80] | 9.71 |

| Irwin et al. (2008) | 0.96 | [0.479, 1.44] | 13.82 |

| Saarto et al. (2012) | 0.03 | [−0.15, 0.20] | 27.86 |

| Vallance, Courneya, Plotnikoff, Yasui, & Mackey (2007); Vallance, Courneya, Plotnikoff, & Mackey (2008); Vallance, Plotnikoff, Karvinen, Mackey, & Courneya (2010) | 0.23 | [0.088, 0.38] | 24.36 |

| Pooled effect size | 0.28 | [0.043, 0.52] | 100 |

Standardized mean differences (SMD) for behavior change effects calculated using Hedge’s g.

Discussion

Appropriate use of theory and theoretical determinants are believed to enhance intervention effectiveness, especially for physical activity in breast cancer survivors (Fishbein & Yzer, 2003; McEachan, Lawton, Jackson, Conner, & Lunt, 2008; Phillips & McAuley, 2013; Vallance, Courneya, Plotnikoff, & Mackey, 2008). The results of this study suggest that while theory use was considered a necessary component in achieving physical activity behavior change in most trials, its application was generally insubstantial. Most studies clearly articulated at least one theoretical framework and presented evidence about the reasons the theory or theories were hypothesized to be related to physical activity behavior. However, in many cases, the presentation of theoretical application diminished in the later stages of intervention planning and evaluation, such that explicit linkages between constructs, measurement, and interpretation of the results in relation to the theory or theories were lacking.

The results of this study suggest that a more focused, consistent application of theory during intervention development, implementation, and evaluation may enhance its effectiveness in producing behavior change. Although the difference in effectiveness when stratified by theory use was modest, this finding is consistent with broader insights about the value of behavior theory in behavior change research (Painter et al., 2008). Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have provided compelling evidence that theory use improved the efficacy of physical activity interventions tested in adult populations (Gourlan et al., 2014) and specifically in interventions for survivors (Short et al., 2013). Gourlan et al. (2014), however, suggested that general improvements in physical activity from theory-based interventions still require more investigation to understand the specific contribution of intervention components on their effects. For breast cancer survivors in particular, current research suggests that participants in interventions targeting theoretical determinants may be more likely to make and sustain lifestyle changes (Loprinzi, Cardinal, Si, Bennett, & Winters-Stone, 2012), although determinants for longer term physical activity maintenance require further study (Brug, Oenema, & Ferreira, 2005; Pinto & Ciccolo, 2011).

The results of our analysis revisit the debate among researchers that differentiates theory-informed interventions from truly theory-based interventions (French et al., 2012; Michie & Abraham, 2004). The interventions reviewed frequently described theory-informed approaches, that is, those that vaguely describe a theory of interest but were not explicit about how it was used. However, most studies did not report using a formal process by which to make the claim that interventions were truly theory based. Appropriate theory use would include specifying theoretical aspects of the determinants of the behavior, specifically targeting these determinants with the appropriate theoretical change methods and assuring that methods were used in a manner the theory would suggest to maximize effectiveness (Bartholomew & Mullen, 2011; Peters, de Bruin, & Crutzen, 2013; Rhodes & Pfaeffli, 2010). A systematic, problem-driven approach, such as the Intervention Mapping protocol (Bartholomew, Parcel, Kok, Gottlieb, & Fernandez, 2011) or the Theoretical Domains Framework (French et al., 2012), may enhance planning and reporting of theory application and contribute to evidence for appropriate behavior change strategies and overall theoretical coherence (Gardner, Whittington, McAteer, Eccles, & Michie, 2010).

Selection of theory-based methods is a particular challenge for program planners. Even if a method is properly chosen, researchers require knowledge of the underlying theory to understand what will make the method “work.” The parameters (i.e., the required conditions) of how theory and theory-based methods are applied can themselves be important determinants of intervention effectiveness (Peters et al., 2013). In survivorship research, these critical elements of what is needed, for whom, and under what circumstances has also been called out as a future research direction to improve lifestyle behavioral interventions for cancer survivors (Buffart, Galvão, Brug, Chinapaw, & Newton, 2014).

Strengths and Limitations

This study had several strengths. First, it offered an innovative approach, applying a modified framework for assessment of theory use in combination with evidence generated by systematic review and meta-analytic methods. The framework proposed by Michie and Prestwich (2010) was designed for a similar purpose and intended to complement guidelines proposed by CONSORT and others to critically assess methodological quality in scientific studies. Another strength of our study was that all data came from randomized controlled trials; thus, inferences about general effects of the intervention on physical activity behavior were less likely to be subject to sources of bias that may affect internal validity. Additionally, customizing a set of descriptors on theory use for these physical activity behavioral studies provided a basis from which to deconstruct and characterize theory application, comparing its use across a similar group of interventions targeting the same behavior in similar study designs. We also know from our original study that study quality was generally high in the selected set of studies we reviewed (Bluethmann et al., 2015), so that provided a strong foundation from which to separately evaluate theory use. Furthermore, while we assessed the role of intervention delivery relative to supervision in the original study, one of our primary findings was that in-person supervision was not vastly more effective than other modes of delivery (e.g., phone or email counseling). We were able to use these findings as part of our overall assessment of the role of theory in effectiveness of these interventions.

Although this study offered some innovative approaches, there were limitations. The practice of pooling data, while useful in summarizing results, may have resulted in loss of information about how these interventions influenced behavior changes. Additionally, the ability to characterize how theory was used according to our criteria depended in part on the clarity and quality of the reporting of published trials. Given the limited number of theories represented in the selected studies and the common approach to combine theories, we were not able to conduct theory-specific analysis relative to intervention effectiveness, but this may be an opportunity for future research. Insufficient reporting detail limited the ability to provide a more extensive comparison of the theoretical methods used across studies. However, using two coders trained in health promotion may have enhanced the reliability of theory coding decisions, increasing the contribution of theory use as part a broader assessment of intervention effectiveness. We believe the approach used in this report will also support program planners as they make fine-grained distinctions in how theory should be applied and evaluated. Although our review was not limited to interventions administered in clinical settings, we believe there are potential clinical implications for using theory to improve clinic-based interventions to promote physical activity, especially in breast cancer survivors.

Conclusion

Theory use is generally recognized as a core component to successfully changing physical activity and other behaviors, but the interpretation of what it means to use theory appropriately varies widely. Guidelines for systemically reported theory use could be better utilized. This study provided insight on how theory was approached and how its use compared among interventions that were all designed to change physical activity behavior in posttreatment breast cancer survivors. There was some evidence to suggest that the extent of theory use enhanced intervention effectiveness in our exploratory study. However, there is much more to learn about how theory can benefit interventions for breast cancer survivors and to effectively evaluate the way theory is used. Further testing of behavioral models with mediation analysis may provide a better understanding of how theoretical constructs used in interventions may affect behavioral outcomes. Applying better methods to evaluate theoretical coherence may improve intervention design and, in doing so, influence opportunities for physical activity behavior change, especially as research targeting post-treatment breast cancer survivors continues to accelerate.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Bluethmann is currently a Cancer Prevention Fellow at the National Cancer Institute. Previously, she was supported by the Susan G. Komen Foundation (KG111378) and the Cancer Education and Career Development Program at the School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, funded by the National Cancer Institute (R25CA57712). The findings and conclusions in this presentation are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the Komen Foundation or the National Cancer Institute, the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

References marked with an asterisk are included in the review.

- Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychology. 2008;27:379–387. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard-Barbash R, Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Siddiqi SM, McTiernan A, Alfano CM. Physical activity, biomarkers, and disease outcomes in cancer survivors: A systematic review. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2012;104:815–840. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew LK, Mullen PD. Five roles for using theory and evidence in the design and testing of behavior change interventions. Journal of Public Health Dentistry. 2011;71(Suppl 1):S20–S33. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Fernandez ME. Planning health promotion programs: An intervention mapping approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- *.Basen-Engquist K, Taylor CL, Rosenblum C, Smith MA, Shinn EH, Greisinger A, … Rivera E. Randomized pilot test of a lifestyle physical activity intervention for breast cancer survivors. Patient Education & Counseling. 2006;64:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Bloom JR, Stewart SL, D’Onofrio CN, Luce J, Banks PJ. Addressing the needs of young breast cancer survivors at the 5 year milestone: Can a short-term, low intensity intervention produce change? Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2008;2:190–204. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluethmann SM, Vernon SW, Gabriel KP, Murphy CC, Bartholomew LK. Taking the next step: A systematic review and meta-analysis of physical activity and behavior change interventions in recent post-treatment breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2015;149:331–342. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3255-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brug J, Oenema A, Ferreira I. Theory, evidence and intervention mapping to improve behavior nutrition and physical activity interventions. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2005;2(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffart LM, Galvão DA, Brug J, Chinapaw MJM, Newton RU. Evidence-based physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors: Current guidelines, knowledge gaps and future research directions. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2014;40:327–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Daley AJ, Crank H, Saxton JM, Mutrie N, Coleman R, Roalfe A. Randomized trial of exercise therapy in women treated for breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:1713–1721. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.5083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R, Campbell R, Hildon Z, Hobbs L, Michie S. Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: A scoping review. Health Psychology Review. 2014;9:323–344. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2014.941722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Yzer MC. Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Communication Theory. 2003;13:164–183. [Google Scholar]

- French SD, Green SE, O’Connor DA, McKenzie JE, Francis JJ, Michie S, … Grimshaw JM. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: A systematic approach using the theoretical domains framework. Implementation Science. 2012;7(1):38. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner B, Whittington C, McAteer J, Eccles MP, Michie S. Using theory to synthesise evidence from behaviour change interventions: The example of audit and feedback. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:1618–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.soc-scimed.2010.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annual Review of Public Health. 2010;31:399–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourlan M, Bernard P, Bortholon C, Romain A, Lareyre O, Carayol M, … Boiché J. Efficacy of theory-based interventions to promote physical activity. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Health Psychology Review. 2014;10:50–66. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2014.981777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Greenlee HA, Crew KD, Mata JM, McKinley PS, Rundle AG, Zhang W, … Hershman DL. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a commercial diet and exercise weight loss program in minority breast cancer survivors. Obesity. 2013;21:65–76. doi: 10.1002/oby.20245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hatchett A, Hallam JS, Ford MA. Evaluation of a social cognitive theory-based email intervention designed to influence the physical activity of survivors of breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22:829–836. doi: 10.1002/pon.3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Irwin ML, Cadmus L, Alvarez-Reeves M, O’Neil M, Mierzejewski E, Latka R, … Knobf M. Recruiting and retaining breast cancer survivors into a randomized controlled exercise trial. Cancer. 2008;112(Suppl 11):2593–2606. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kim SH, Shin MS, Lee HS, Lee ES, Ro JS, Kang HS, … Yun YH. Randomized pilot test of a simultaneous stage-matched exercise and diet intervention for breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2011;38:E97–E106. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.E97-E106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latka RN, Alvarez-Reeves M, Cadmus L, Irwin ML. Adherence to a randomized controlled trial of aerobic exercise in breast cancer survivors: the Yale exercise and survivorship study. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2009;3:148–157. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0088-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemanne D, Cassileth B, Gubili J. The role of physical activity in cancer prevention, treatment, recovery, and survivorship. Oncology (Williston Park) 2013;27:580–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Ligibel JA, Meyerhardt J, Pierce JP, Najita J, Shockro L, Campbell N, … Shapiro C. Impact of a telephone-based physical activity intervention upon exercise behaviors and fitness in cancer survivors enrolled in a cooperative group setting. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2011;132:205–213. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1882-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippke S, Jochen P. Theory-based health behavior change: Developing, testing, and applying theories for evidence-based interventions. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2008;57:698–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00339.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loprinzi PD, Cardinal BJ, Si Q, Bennett JA, Winters-Stone KM. Theory-based predictors of follow-up exercise behavior after a supervised exercise intervention in older breast cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012;20:2511–2521. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1360-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Matthews CE, Wilcox S, Hanby CL, Der Ananian C, Heiney SP, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A. Evaluation of a 12-week home-based walking intervention for breast cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2007;15:203–211. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEachan RR, Lawton RJ, Jackson C, Conner M, Lunt J. Evidence, theory and context: Using intervention mapping to develop a worksite physical activity intervention. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:326. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely ML, Campbell KL, Rowe BH, Klassen TP, Mackey JR, Courneya KS. Effects of exercise on breast cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2006;175:34–41. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, Abraham C. Interventions to change health behaviours: Evidence-based or evidence-inspired? Psychology & Health. 2004;19:29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, Prestwich A. Are interventions theory-based? Development of a theory coding scheme. Health Psychology. 2010;29:1–8. doi: 10.1037/a0016939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikander R, Sievanen H, Ojala K, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Palva T, Blomqvist C, … Saarto T. Effect of exercise on bone structural traits, physical performance and body composition in breast cancer patients–a 12-month RCT. Journal of Musculoskeletal Neuronal Interactions. 2012;12:127–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter JE, Borba CP, Hynes M, Mays D, Glanz K. The use of theory in health behavior research from 2000 to 2005: A systematic review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;35:358–362. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9042-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penttinen H, Nikander R, Blomqvist C, Luoto R, Saarto T. Recruitment of breast cancer survivors into a 12-month supervised exercise intervention is feasible. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2009;30:457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters GY, de Bruin M, Crutzen R. Everything should be as simple as possible, but no simpler: Towards a protocol for accumulating evidence regarding the active content of health behaviour change interventions. Health Psychology Review. 2013;9:1–14. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2013.848409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SM, McAuley E. Social cognitive influences on physical activity participation in long-term breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22:783–791. doi: 10.1002/pon.3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto BM, Ciccolo JT. Physical activity motivation and cancer survivorship. Recent Results in Cancer Research. 2011;186:367–387. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-04231-7_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto BM, Floyd A. Theories underlying health promotion interventions among cancer survivors. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2008;24:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Pinto BM, Frierson GM, Rabin C, Trunzo JJ, Marcus BH. Home-based physical activity intervention for breast cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:3577–3587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Pinto BM, Papandonatos GD, Goldstein MG. A randomized trial to promote physical activity among breast cancer patients. Health Psychology. 2013;32:616–626. doi: 10.1037/a0029886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto BM, Rabin C, Dunsiger S. Home-based exercise among cancer survivors: adherence and its predictors. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18:369–376. doi: 10.1002/pon.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto BM, Rabin C, Papandonatos GD, Frierson GM, Trunzo JJ, Marcus B. Maintenance of effects of a home-based physical activity program among breast cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2008;16:1279–1289. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0434-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prestwich A, Sniehotta FF, Whittington C, Dombrowski SU, Rogers L, Michie S. Does theory influence the effectiveness of health behavior interventions? meta-analysis. Health Psychology. 2013;33:465–474. doi: 10.1037/a0032853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinsen H, Bleijenberg G, Heijmen L, Zwarts MJ, Leer JWH, Heerschap A, … Van Laarhoven HWM. The role of physical activity and physical fitness in postcancer fatigue: A randomized controlled trial. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013;21:2279–2288. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1784-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1997;12:38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes RE, Pfaeffli LA. Review mediators of physical activity behaviour change among adult non-clinical populations: A review update. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2010;7:37–48. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Meyerhardt J, Courneya KS, Schwartz AL, … Gansler T. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2012;62:242–274. doi: 10.3322/caac.21142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Rogers LQ, Hopkins-Price P, Vicari S, Pamenter R, Courneya KS, Markwell S, … Lowy M. A randomized trial to increase physical activity in breast cancer survivors. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2009;41:935–946. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818e0e1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman AJ. “Is there nothing more practical than a good theory?” Why innovations and advances in health behavior change will arise if interventions are used to test and refine theory. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition & Physical Activity. 2004;1:11. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Saarto T, Penttinen HM, Sievanen H, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Hakamies-Blomqvist L, Nikander R, … Luoma ML. Effectiveness of a 12-month exercise program on physical performance and quality of life of breast cancer survivors. Anticancer Research. 2012;32:3875–3884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabiston CM, Brunet J. Reviewing the benefits of physical activity during cancer survivorship. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2012;6:167–177. doi: 10.1177/1559827611407023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Short CE, James EL, Stacey F, Plotnikoff RC. A qualitative synthesis of trials promoting physical activity behaviour change among post-treatment breast cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship: Research and Practice. 2013;7:570–581. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0296-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SG, Chagpar AB. Adherence to physical activity guidelines in breast cancer survivors. The American Surgeon. 2010;76:962–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor N, Conner M, Lawton R. The impact of theory on the effectiveness of worksite physical activity interventions: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Health Psychology Review. 2012;6:33–73. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2010.533441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Vallance J, Plotnikoff RC, Karvinen KH, Mackey JR, Courneya KS. Understanding physical activity maintenance in breast cancer survivors. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2010;34(2):225–236. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.34.2.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Vallance JK, Courneya KS, Plotnikoff RC, Dinu I, Mackey JR. Maintenance of physical activity in breast cancer survivors after a randomized trial. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2008;40:173–180. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3181586b41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Vallance JK, Courneya KS, Plotnikoff RC, Mackey JR. Analyzing theoretical mechanisms of physical activity behavior change in breast cancer survivors: Results from the activity promotion (ACTION) trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;35:150–158. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallance JK, Courneya KS, Plotnikoff RC, Yasui Y, Mackey JR. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of print materials and step pedometers on physical activity and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:2352–2359. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace LM, Brown KE, Hilton S. Planning for, implementing and assessing the impact of health promotion and behaviour change interventions: A way forward for health psychologists. Health Psychology Review. 2014;8:8–33. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2013.775629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]