Abstract

Bladder cancer (BC) is one of the most commonly occurring cancers, with a high recurrence rate and poor outcomes in cases of relapsed metastatic disease. Here, we analyzed the markers and significance of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) for BC development and progression. MDSC markers were examined in peripheral blood from 113 BC patients and 20 healthy volunteers. We identified CD11b+CD33lowHLA-DR− CD3− cells as markers of MDSCs in peripheral blood from BC patients. We also demonstrated that MDSC numbers are higher in BC patients than healthy donors, and that MDSC numbers correlate with the clinical grade, stage, and poor prognosis. In addition, serum IL-6 levels are decreased in BC patients with higher MDSC counts. IL-6 blockade increases induction of MDSCs in vitro. Low IL-6 levels inhibit activation of Stat3, resulting in the increased formation of MDSCs in BC. These results indicate that the MDSCs numbers may serve as a novel prognostic marker in BC patients, and that targeting IL-6 signaling may be a promising strategy for BC treatment.

Keywords: MDSCs, bladder cancer, IL-6, immune suppression, prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Bladder cancer (BC) is the second most common genitourinary malignancy [1]. At initial diagnosis, 75% of BC patients present with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) and can be managed with transurethral resection (TUR) and intravesical therapy. The remaining 25% of BC patients present with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC), for which the standard treatment is radical cystectomy (RC), and which is frequently associated with metastatic disease and increased mortality. Despite improvement in surgical techniques, 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) rates after RC remain between 50 and 70% [2–4].

Previous studies have revealed a strong correlation between inflammation and cancer incidence [5, 6], suggesting that immune cells play an important role in cancer development and progression. Chronic inflammation contributes to tumor initiation and progression via both non-immune and immune mechanisms [7]. Most cancers are characterized by the overproduction of immunosuppressive cells and cytokines [8]. In particular, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) have become the focus of intense study in recent years because of their important role in tumor-associated immune suppression. MDSCs represent a heterogeneous population of cells consisting of myeloid progenitor cells and immature myeloid cells that can suppress T cell responses [9]. In mice, MDSCs are characterized by the expression of CD11b and Gr-1, while in humans, the MDSCs markers are variable, and depend on the type of malignancy. Human MDSCs are generally considered to be myeloid-derived, non-lineage determined, and with poor antigen presentation capacity. The phenotypes of MDSCs isolated from different types of cancer patients have been identified [10–13]. Increased numbers of MDSCs have been observed in various solid and hematologic malignancies, and have been associated with cancer progression and tumor-induced immune dysfunction [14–16].

Although increased accumulation of MDSCs has been reported in patients with BC [17], the specific MDSCs markers and underlying mechanisms remain unknown. Therefore, in this study, we assessed the predictive value of MDSCs in patients with BC. In addition, MDSCs are induced and/or activated by pro-inflammatory mediators [18–20]. If inflammation-induced MDSCs are an important link between inflammation and cancer, then the regulation of inflammatory mediators could affect MDSCs levels and delay tumor progression. To assess this hypothesis, we evaluated the relationship between cytokines responsible for the accumulation and activities of MDSCs and the amount of circulating MDSCs in BC patients. Our results demonstrate that decreased levels of IL-6 contribute to the accumulation of MDSCs in BC patients, suggesting novel strategies for the development of immune-based therapies.

RESULTS

MDSCs in BC patients are CD11b+CD33lowHLA-DR−CD3− cells

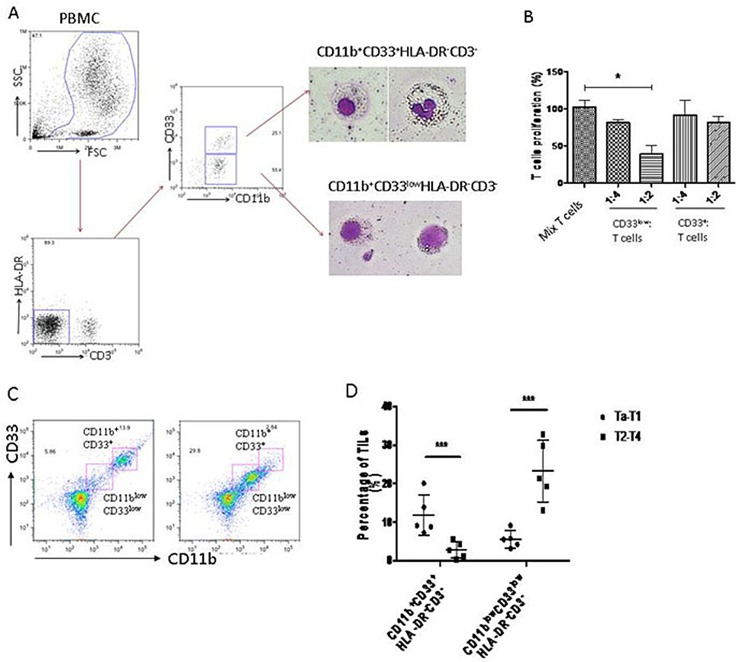

The cell surface markers for human MDSCs are variable in different types of tumors. To determine the MDSCs phenotype in BC patients, we isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from peripheral blood of BC patients, and stained them with common MDSCs markers. The results showed that there were two main groups of immature myeloid cells (CD11b+HLA-DR−CD3−) in PBMC of BC patients: one was CD33low, and the other was CD33+ (Figure 1A). These cells were isolated by flow-cytometry and stained by Giemsa. The morphology showed that CD33+ cells had segmented nuclei like mature granulocytes, while CD33low cells had big and round nuclei like immature myeloid cells (Figure 1A). To confirm that the CD11b+CD33lowHLA-DR−CD3−cells are MDSCs, we examined their suppressive effects on T cell proliferation. The results showed that CD33low cells significantly inhibited T cell proliferation, suggesting that the CD33low CD11b+HLA-DR−CD3− cells are MDSCs of BC patients (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. MDSCs of human bladder cancer are defined as CD11b+CD33lowHLA-DR−CD3− cells.

(A) Flow cytometry was performed on freshly isolated PBMCs from BC patients. Morphological characterization of myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) sorted and analyzed by Giemsa staining. (B) Circulating CD11b+CD33lowHLA-DR−CD3− cells suppress autologous T cell proliferation at a 2:1 T cell/MDSC ratio (*P < 0.05). (C) MDSCs (CD11blow CD33lowHLA-DR−CD3−) were accumulated in tumor tissue of BC patients. (D) MDSCs (CD11blow CD33lowHLA-DR−CD3−) were dramatically higher in patients at stage of Ta-T1 than those at stage of T2-T4 (***P < 0.01).

To confirm that the MDSCs were present in tumor tissues of BC patients, we collected the BC tumor samples, and analyzed the tumor-infiltrated leukocytes by flow cytometry. The data showed an increased accumulation of MDSCs (CD11blowCD33lowHLA-DR−CD3−) in tumor tissues of BC patients (Figure 1C). The MDSCs accumulation was significantly increased in BC patients with stage Ta-T1 compared to patients with stage T2-T4 (Figure 1D).

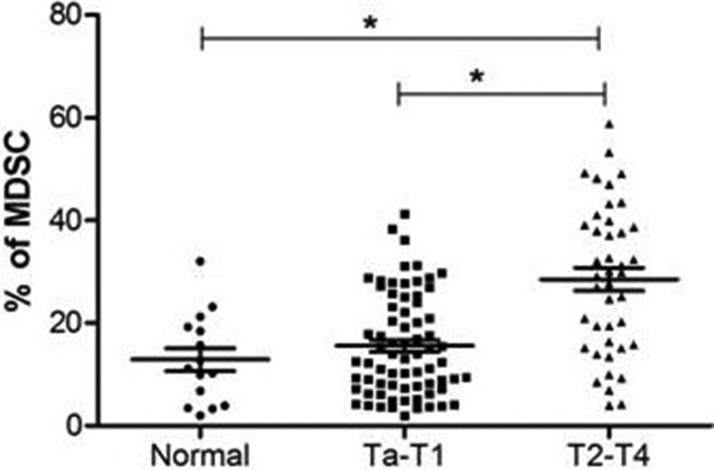

MDSCs are increased in peripheral blood of BC patients at advanced stages

To evaluate the significance of MDSCs on BC prognosis, we investigated the proportion of MDSCs (CD11b+CD33lowHLA-DR−CD3−) cells in BC patients (n = 113) and healthy donors (n = 20). The proportion of MDSCs in peripheral blood from BC patients was significantly increased compared with the proportion from healthy donors. In addition, the level of MDSCs was higher in BC patients at stage of T2-T4 than that of Ta-T1 (P < 0.05) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The percentage of MDSCs is increased in bladder cancer patients.

The proportion of MDSCs in peripheral blood from BC patients was significantly increased compared with the proportion from healthy donors, and the level of MDSC was higher in BC patients at stage of T2-T4 than that of Ta-T1 (*P < 0.05).

Correlation between MDSCs and clinicopathological features

To determine the clinical significance of MDSCs, 113 BC patients were enrolled and divided into two groups according to the frequency of MDSCs. Values that were higher than the mean of all tumors were considered elevated. For the low group, the frequency of MDSCs was defined as less than or equal to 21%, whereas for the high group, the frequency of MDSCs was greater than 21%. We found that the higher frequency of MDSCs was associated with tumor grade and stage (P = 0.009 and P < 0.001, respectively). However, the higher frequency of MDSCs was not associated with other clinicopathological features, such as age, sex, tumor size, and tumor number (Table 1).

Table 1. Correlations between the proportion of MDSC and clinicopathological features in 113 patients with bladder cancer.

| Parameter | Case | MDSC expression | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | |||

| Sex | 0.367 | |||

| Female | 34 | 18 | 16 | |

| Male | 79 | 49 | 30 | |

| Age (years) | 0.602 | |||

| ≤ 65 | 41 | 23 | 18 | |

| > 65 | 72 | 44 | 28 | |

| Tumor size(cm) | 0.450 | |||

| ≤ 3 | 74 | 42 | 32 | |

| > 3 | 39 | 25 | 14 | |

| Tumor number | 0.127 | |||

| Unifocal | 64 | 34 | 30 | |

| Multifocal | 49 | 33 | 16 | |

| Grade | 0.009 | |||

| low | 38 | 29 | 9 | |

| high | 75 | 38 | 37 | |

| T stage | < 0.0001 | |||

| pTa- pT1 | 71 | 51 | 20 | |

| pT2- pT4 | 42 | 16 | 26 | |

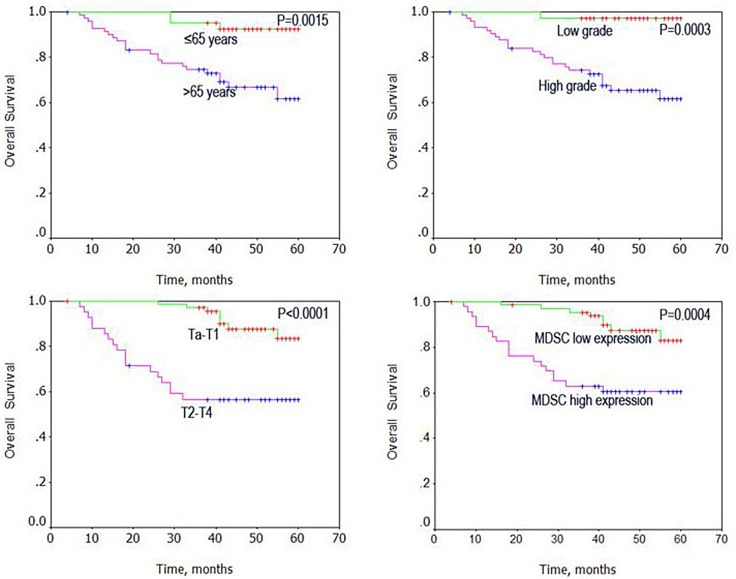

Circulating MDSCs levels correlate with poor outcome in BC patients

Using Kaplan–Meier analysis method, we observed that age, grade, stage, and high MDSCs levels correlated with OS (both P < 0.001, Table 2). The log-rank test further demonstrated that the overall survival time was associated with age, grade, stage, and high MDSCs levels (Figure 3). Multivariate analysis was also performed with the Cox proportional hazards model including gender, age, tumor size, number, grade, and stage, and the MDSCs levels. The results showed that the MDSCs levels correlated with BC prognosis, and were an independent prognostic factor for patients with BC (P = 0.006; Table 3)

Table 2. Univariate survival analysis of overall survival in 113 patients with BC.

| Variable | case | Overall survival | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE(month) | 95%CI | P value | ||

| Gender | 0.415 | |||

| Female | 34 | 49 ± 3 | (43–54) | |

| Male | 79 | 52 ± 2 | (49–56) | |

| Age (yeas) | 0.0015 | |||

| ≤ 65 | 41 | 58 ± 1 | (56–60) | |

| > 65 | 72 | 48 ± 2 | (43–52) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.6294 | |||

| ≤ 3 | 74 | 52 ± 2 | (48–56) | |

| > 3 | 39 | 50 ± 3 | (45–55) | |

| Tumor number | 0.5258 | |||

| Unifocal | 64 | 53 ± 2 | (49–56) | |

| Mutlifocal | 49 | 50 ± 3 | (45–55) | |

| Grade | 0.0003 | |||

| Low | 38 | 59 ± 1 | (57–60) | |

| High | 75 | 48 ± 2 | (43–52) | |

| T stage | < 0.0001 | |||

| Ta-T1 | 71 | 57 ± 1 | (55–59) | |

| T2-T4 | 42 | 42 ± 3 | (35–48) | |

| Proportion of MDSC | 0.0004 | |||

| Low | 67 | 57 ± 1 | (44–59) | |

| High | 46 | 44 ± 3 | (38–50) | |

Figure 3. Univariate analysis of overall survival in patients with bladder cancer using the Kaplan Meier method.

Table 3. Multivariate analyses of clinicopathological factors for the overall survival of the patients with BC.

| Variable | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P value | |

| Gender | 0.610 | ||

| Male vs female | 0.797 | 0.333–1.908 | |

| Age(years) | 0.002 | ||

| ≤ 65 vs > 65 | 6.940 | 1.994–24.148 | |

| Tumor number | 0.954 | ||

| Unifocal vs mutlifocal | 1.027 | 0.413–2.551 | |

| Tumor size(cm) | 0.579 | ||

| ≤ 3 vs > 3 | 0.782 | 0.327–1.867 | |

| Grade | 0.066 | ||

| Low vs high | 7.243 | 0.878–59.746 | |

| T stage | 0.062 | ||

| pTa- pT1 vs pT2- pT4 | 2.586 | 0.955–7.006 | |

| Proportion of MDSC | 0.006 | ||

| Low vs high | 3.582 | 1.448–8.861 | |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval.

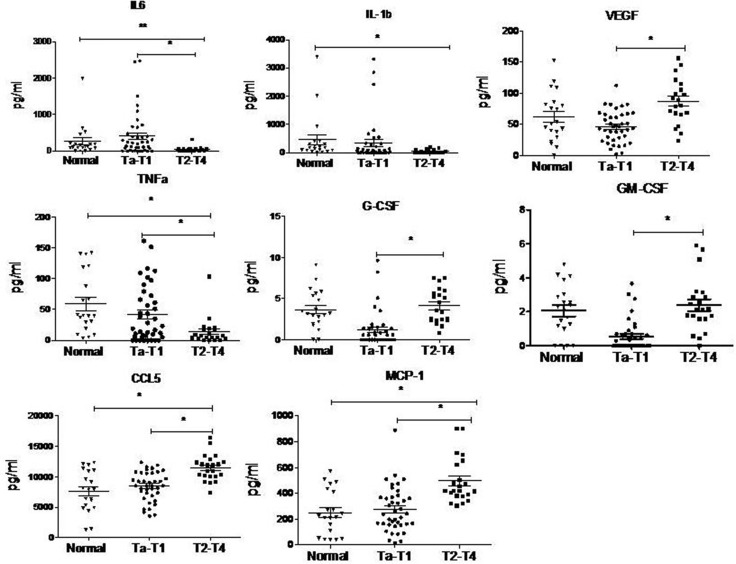

Serum levels of MDSC-inducing cytokines differ between Ta-T1 and T2-T4 stages in BC patients

Tumor cells or stroma cells in tumor environment can release soluble factors that affect the differentiation of myeloid cells [21]. Some cytokines, such as GM-CSF, G-CSF, VEGF, or IL-3, play an important role in myelopoiesis [22], while other cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-6, contribute to the immunosuppressive activity of MDSCs [23].

To explore the mechanism responsible for the formation of MDSCs in BC patients, we examined the serum levels of MDSCs-inducing cytokines in BC patients by cytometric beads assay. Serum was obtained from 20 healthy donors and 61 BC patients. The levels of VEGF, G-CSF, GM-CSF, CCL5, and MCP-1 were increased, while the levels of IL-6, IL-1β and TNFα were decreased in BC patients with T2-T4 stage, compared to BC patients with Ta-T1 stage, and healthy controls (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Cytokine levels in serum of BC patients analyzed by cytometric beads assay.

The levels of VEGF, G-CSF, GM-CSF, CCL5 and MCP-1 are up-regulated while the levels of IL-6, IL-1b and TNFα are down-regulated in BC patients with T2-T4 stage, compared to BC patients with Ta-T1 stage and healthy control. (*P < 0.05)

Low level of IL-6 is sufficient to induce MDSCs formation in vitro

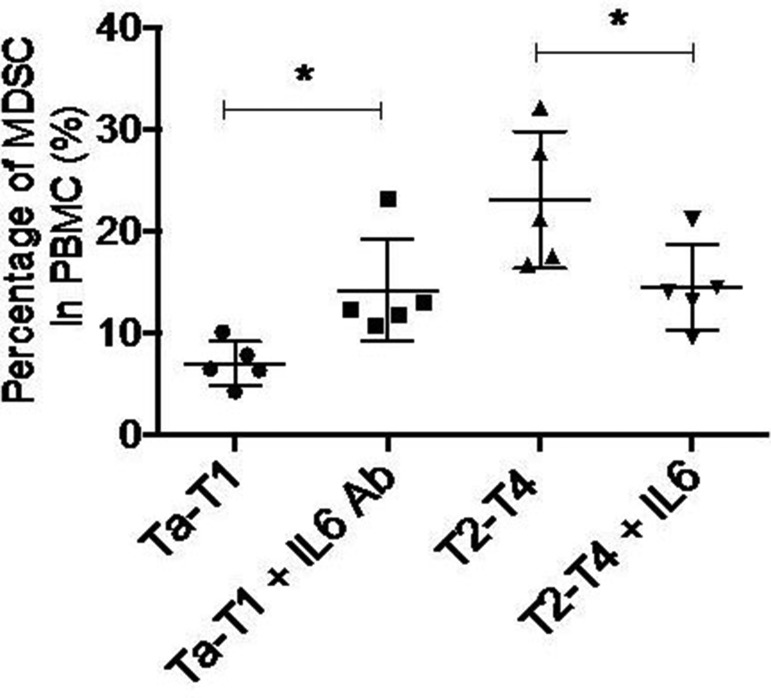

Among the eight cytokines examined by cytometric beads assay, only the levels of IL-6, TNFα, CCL5, and MCP-1 were significantly changed in both Ta-T1/T2-T4 and control/T2-T4 BC patients. To determine which specific cytokine contributes to the accumulation of MDSCs in stages T2-T4, we induced MDSCs formation in vitro by adding individual cytokines or corresponding neutralizing antibodies. The results showed that adding exogenous IL-6 to serum obtained from BC patients in T2-T4 stage significantly decreased the accumulation of MDSCs, while adding IL-6 neutralizing antibody (5E1) to serum of BC patients in Ta-T1 stage increased the number of MDSCs (Figure 5). Modulation of TNFα, CCL5, or MCP-1 levels had no effect on MDSCs accumulation (data not shown). These data suggest that low levels of IL-6 induce the differentiation of MDSCs cells.

Figure 5. Down-regulation of IL6 is sufficient to induce MDSC formation in vitro.

Adding exogenous IL6 to serum gotten from BC patients in T2-T4 stage significantly undermined the accumulation of MDSC, while adding IL6 neutralizing antibody (5E1) to serum of BC patients in Ta-T1 stage increased the number of MDSC(*P < 0.05).

Stat3, but not NF-kB, regulates IL-6-mediated differentiation of MDSCs

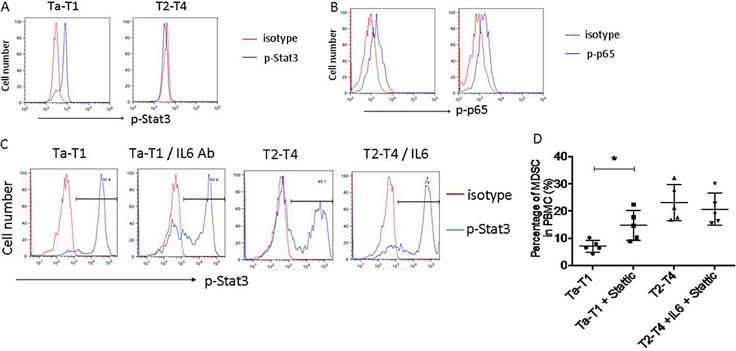

To investigate the signaling pathways involved in the IL-6-mediated MDSCs differentiation, we examined the IL-6-induced activation of NF-κB (phosphorylation of p65) and Stat3 (phosphorylation of Stat3) pathways in CD11b+ myeloid cells in BC patients in T2-T4 and Ta-T1 stages. Phosphorylation of Stat3, but not p65, was decreased in BC patients in T2-T4 stages, compared to Ta-T1 stages (Figure 6A and 6B). To confirm the role of IL-6/Stat3 in the differentiation of MDSCs, we examined the levels of p-Stat3 in MDSCs induced by serum of BC patients. Figure 6C shows that Stat3 phosphorylation was decreased by adding serum from BC patients at stages T2-T4, and that it was regulated by adding IL-6 protein or IL-6 neutralizing antibody.

Figure 6. Stat3, but not NF-kB, regulates differentiation of MDSC induced by low levels of IL-6.

(A and B) The phosphorylation of Stat3, not that of p65, is dramatically down-regulated in patients in T2-T4, compared to those in Ta-T1. (C) In the experiment of induction of MDSC in vitro, the phosphorylation of Stat3 was dramatically inhibited by serum of BC patients at stage of T2– T4, and the level of p-Stat3 was regulated by adding IL6 protein or IL6 neutralizing antibody. (D) The effect of Stattic on MDSC formation induced by serums of BC patients in vitro.

To examine the effect of IL-6/STAT3 signaling on MDSCc formation, we used the STAT3 inhibitor, Stattic (10 μM). In the presence of serum from Ta-T1 BC patients, Stattic significantly increased the percentage of MDSCs compared to the control group. In the presence of serum from T2-T4 BC patients, Stattic blocked the IL6-induced inhibition of MDSCs (Figure 6D). Together, our data indicate that the IL-6/Stat3 signaling plays an important role in the differentiation of MDSCs.

DISCUSSION

The immune system plays a pivotal role in the development, progression, and metastasis of human BC. Although the precise mechanisms remain elusive, clinical studies have indicated that MDSCs promote tumor progression and present an important barrier limiting the full potential of immune-based cancer therapies [24]. Additionally, MDSCs have been associated with poor prognosis in several types of cancer [7, 8, 25].

In the present study, we have identified the markers for MDSCs in Chinese BC patients and characterized the percentage of CD33lowCD11b+HLA-DR−CD3−myeloid cells in BC patients. The data revealed that the number of CD33−CD11b+HLA-DR− CD3−cells significantly increased in the PBMC of BC patients compared with healthy donors. Since these cells exerted potent immunosuppressive activity on T cells, we have defined them as MDSCs in bladder cancer. Moreover, the proportion of MDSCs cells correlated with BC tumor grade and stage, and could predict a poor outcome.

LIN−HLA−DR−CD33+CD11b+ MDSCs have been identified in patients of glioblastoma, breast cancer, colon cancer, lung cancer, and kidney cancer [14, 15, 26–28]. Previous studies have shown that the number of these myeloid cells may reflect the clinical stages of tumors, and positively correlate with poor prognosis in patients with breast and colorectal cancer [14–16]. It is important that the phenotype of MDSCs appears to be influenced by the type of cancer [21], such as in renal cancer, CD11b+CD14−CD15+CD66b+VEGFR1+ cells have immunosuppressive activity [29]. A recent study performed by USA researchers has shown that innate granulocytes with phenotypes of CD15hiCD33low in blood, and CD11b+CD15+HLA-DR− in tumor tissues, are increased and activated in BC patients, and that these cells exert immunosuppressive activity on T cell proliferation in vitro [17]. However, in Chinese BC patients, we did not observe a significant difference in CD15 expression in myeloid cells, and we identified CD11b+CD33lowHLA-DR− CD3− as the markers for MDSCs, which are significantly increased in BC patients at stages of T2-T4.

MDSCs are recruited by multiple pro-inflammatory molecules secreted by cancer or stroma cells to the tumor sites where they exploit a plethora of redundant mechanisms to inhibit immune responses, including depleting required nutrients for lymphocytes, generating oxidative stress, interfering with lymphocyte trafficking and viability, and activating and expanding the T-reg population [21, 28]. Recent evidence suggests that MDSCs accumulation is induced by numerous cytokines and soluble mediators, including macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), G-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IL-6, IL-1, TNF, and S100A8/S100A9 [30–36]. Our study shows that IL-6 levels are decreased in BC patients compared with healthy donors. Moreover, there is a significant correlation between plasma IL-6 levels and frequency of MDSCs.

IL-6 is a multifunctional cytokine that plays an important role in a wide range of biologic activities in different cell types, including inflammatory and tumor cells. Our study shows that the decreased levels of IL-6 in PBMC promote the formation of MDSCs in vitro, and enhance the immunosuppressive functions of PBMC. Stat3 is a transcription factor important for myeloid lineage development and differentiation. Activation of Stat3 increases macrophage defects and MDSCs expansion [37]. Stat3 signaling in MDSCs may also be potentially modulated by IL-6 [23, 38].

An important finding in this study is that IL-6 inhibits the accumulation of MDSCs via the activation of Stat3, but not NF-κB. Activation of Stat3 and NF-κB regulates the expression of apoptotic, proliferative and immune response genes [35, 39–41]. Inhibition of NF-κB and Stat3 activation has become an effective therapeutic anti-cancer strategy [41–43]. We found that the activation of Stat3, but not NF-κB, is inhibited in MDSCs, because of the decreased levels of IL-6.

In summary, our study indicates that the levels of MDSCs may predict the prognosis of BC patients. Moreover, decreased expression of IL-6 increases MDSCs accumulation, thus providing the immunosuppressive microenvironment for the development of bladder cancer. Therefore, targeting the IL-6 signaling may be a promising strategy for the treatment of bladder cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Blood samples from BC patients and healthy donors were collected from our hospital between January 2010 and December 2011. The criteria for study enrollment were histopathological diagnosis of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder, newly diagnosed and untreated, no history of other tumor, and the potential for follow up. We excluded carcinoma in situ from our study. Prior patient's consent was obtained from all patients and healthy donors. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital. Clinical information about the samples is described in detail in Table 1. The patients included 79 males and 34 females, ranging between 45 and 84 years (mean age, 66.5 years). The median follow-up time for overall survival (OS) was 43 months at the time of analysis, and ranged from 4 to 60 months. OS was defined as the interval between BC resection and death; patients alive at the end of follow-up were monitored.

Cell isolation and staining

MDSCs were isolated from PBMC using anti-CD33 magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), following manufacturer's instruction. Cells were treated with 10 μg/ml anti-GM-CSF antibody (Ab) and 15 μg/ml anti-CCL5 Ab (R&D system). The immunosuppressive activity of MDSCs was evaluated by their ability to inhibit the proliferation of autologous T cells. T cells were purified from PBMC of autologous donors using CD3+ T-cell enrichment column (R&D Systems), following manufacturer's instruction. T cells were added to MDSCs in a 2:1 ratio, and stimulated by anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation beads (Invitrogen) and IL-2 (100 u/ml). Two days later, 10 mM ErdU was added to the culture and cells were allowed to grow for another 24 h before being harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cytometric bead arrays

Serum levels of IL-6, IL-1β VEGF, TNFα, G-CSF, GM-CSF, CCL5, and MCP-1 were analyzed using the human CBA flex set (BD Pharmingen, USA).

Induction of MDSC in vitro

PBMC from healthy donors were isolated by differential density gradient separation. PBMC were cultured in complete medium with GM-CSF (10 ng/ml) and IL-6 (10 ng/ml) for 7 days. MDSCs were analyzed by flow cytometry, and characterized by the CD11b+CD33lowHLA-DR- CD3- phenotype.

Statistical analysis

Differences between healthy controls and bladder cancer patients were evaluated by the Mann–Whitney U test. The significance of the relationships between MDSCs and clinicopathological parameters was evaluated using chi-squared tests. OS curves were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by log-rank test. The significance of various variables for OS was analyzed by the Cox proportional hazards model in the multivariate analysis. SPSS 11.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analysis. P values < 0 .05 were considered statistically significant. Figures were generated in GraphPad Prism (version 5.0, GraphPad Software).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

FUNDING

This study was also supported by grants from Innovation Fund for translational medicine, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiaotong University (15-ZH3002). Shanghai Health Bureau (No.20164Y0124), the Joint Research Foundation for Innovative Medical Technology of Shanghai Shenkang Hospital Development Center (SHDC12015125).

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghoneim MA, Abdel-Latif M, el-Mekresh M, Abol-Enein H, Mosbah A, Ashamallah A, el-Baz MA. Radical cystectomy for carcinoma of the bladder: 2,720 consecutive cases 5 years later. J Urol. 2008;180:121–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shariat SF, Karakiewicz PI, Palapattu GS, Lotan Y, Rogers CG, Amiel GE, Vazina A, Gupta A, Bastian PJ, Sagalowsky AI, Schoenberg MP, Lerner SP. Outcomes of radical cystectomy for transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a contemporary series from the Bladder Cancer Research Consortium. J Urol. 2006;176:2414–22. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.004. discussion 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein JP, Lieskovsky G, Cote R, Groshen S, Feng AC, Boyd S, Skinner E, Bochner B, Thangathurai D, Mikhail M, Raghavan D, Skinner DG. Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer: long-term results in 1,054 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:666–75. doi: 10.1200/jco.2001.19.3.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–44. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–7. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: linking inflammation and cancer. J Immunol. 2009;182:4499–506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Najjar YG, Finke JH. Clinical perspectives on targeting of myeloid derived suppressor cells in the treatment of cancer. Front Oncol. 2013;3:49. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabrilovich DI, Bronte V, Chen SH, Colombo MP, Ochoa A, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Schreiber H. The terminology issue for myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:425. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3037. author reply 426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoechst B, Ormandy LA, Ballmaier M, Lehner F, Kruger C, Manns MP, Greten TF, Korangy F. A new population of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma patients induces CD4(+)CD25(+)Foxp3(+) T cells. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:234–43. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ko JS, Zea AH, Rini BI, Ireland JL, Elson P, Cohen P, Golshayan A, Rayman PA, Wood L, Garcia J, Dreicer R, Bukowski R, Finke JH. Sunitinib mediates reversal of myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation in renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2148–57. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherman D, Smith C, Marboe C, Mosca R, Weinberger J, Di Tullio M, Homma S. Right atrial angiosarcoma causing a coronary artery fistula: diagnosis by transesophageal echocardiography. Am Heart J. 1993;126:254–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(07)80046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandruzzato S, Solito S, Falisi E, Francescato S, Chiarion-Sileni V, Mocellin S, Zanon A, Rossi CR, Nitti D, Bronte V, Zanovello P. myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion in cancer patients. J Immunol. 2009;182:6562–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diaz-Montero CM, Salem ML, Nishimura MI, Garrett-Mayer E, Cole DJ, Montero AJ. Increased circulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells correlate with clinical cancer stage, metastatic tumor burden, and doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:49–59. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0523-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solito S, Falisi E, Diaz-Montero CM, Doni A, Pinton L, Rosato A, Francescato S, Basso G, Zanovello P, Onicescu G, Garrett-Mayer E, Montero AJ, Bronte V, et al. A human promyelocytic-like population is responsible for the immune suppression mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Blood. 2011;118:2254–65. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-325753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raychaudhuri B, Rayman P, Ireland J, Ko J, Rini B, Borden EC, Garcia J, Vogelbaum MA, Finke J. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation and function in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13:591–9. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eruslanov E, Neuberger M, Daurkin I, Perrin GQ, Algood C, Dahm P, Rosser C, Vieweg J, Gilbert SM, Kusmartsev S. Circulating and tumor-infiltrating myeloid cell subsets in patients with bladder cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:1109–19. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baniyash M. TCR zeta-chain downregulation: curtailing an excessive inflammatory immune response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:675–87. doi: 10.1038/nri1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song X, Krelin Y, Dvorkin T, Bjorkdahl O, Segal S, Dinarello CA, Voronov E, Apte RN. CD11b+/Gr-1+ immature myeloid cells mediate suppression of T cells in mice bearing tumors of IL-1beta-secreting cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:8200–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bunt SK, Yang L, Sinha P, Clements VK, Leips J, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Reduced inflammation in the tumor microenvironment delays the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and limits tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10019–26. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:253–68. doi: 10.1038/nri3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sica A, Bronte V. Altered macrophage differentiation and immune dysfunction in tumor development. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1155–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI31422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marigo I, Bosio E, Solito S, Mesa C, Fernandez A, Dolcetti L, Ugel S, Sonda N, Bicciato S, Falisi E, Calabrese F, Basso G, Zanovello P, et al. Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression depend on the C/EBPbeta transcription factor. Immunity. 2010;32:790–802. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kao J, Ko EC, Eisenstein S, Sikora AG, Fu S, Chen SH. Targeting immune suppressing myeloid-derived suppressor cells in oncology. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;77:12–9. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alizadeh D, Trad M, Hanke NT, Larmonier CB, Janikashvili N, Bonnotte B, Katsanis E, Larmonier N. Doxorubicin eliminates myeloid-derived suppressor cells and enhances the efficacy of adoptive T-cell transfer in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:104–18. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greten TF, Manns MP, Korangy F. Myeloid derived suppressor cells in human diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:802–7. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kusmartsev S, Su Z, Heiser A, Dannull J, Eruslanov E, Kubler H, Yancey D, Dahm P, Vieweg J. Reversal of myeloid cell-mediated immunosuppression in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:8270–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corzo CA, Cotter MJ, Cheng P, Cheng F, Kusmartsev S, Sotomayor E, Padhya T, McCaffrey TV, McCaffrey JC, Gabrilovich DI. Mechanism regulating reactive oxygen species in tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:5693–701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez PC, Ernstoff MS, Hernandez C, Atkins M, Zabaleta J, Sierra R, Ochoa AC. Arginase I-producing myeloid-derived suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma are a subpopulation of activated granulocytes. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1553–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khaled YS, Ammori BJ, Elkord E. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer: recent progress and prospects. Immunol Cell Biol. 2013;91:493–502. doi: 10.1038/icb.2013.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shojaei F, Wu X, Qu X, Kowanetz M, Yu L, Tan M, Meng YG, Ferrara N. G-CSF-initiated myeloid cell mobilization and angiogenesis mediate tumor refractoriness to anti-VEGF therapy in mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6742–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902280106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waight JD, Hu Q, Miller A, Liu S, Abrams SI. Tumor-derived G-CSF facilitates neoplastic growth through a granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell-dependent mechanism. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayne LJ, Beatty GL, Jhala N, Clark CE, Rhim AD, Stanger BZ, Vonderheide RH. Tumor-derived granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor regulates myeloid inflammation and T cell immunity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:822–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao X, Rong L, Zhao X, Li X, Liu X, Deng J, Wu H, Xu X, Erben U, Wu P, Syrbe U, Sieper J, Qin Z. TNF signaling drives myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4094–104. doi: 10.1172/JCI64115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng P, Corzo CA, Luetteke N, Yu B, Nagaraj S, Bui MM, Ortiz M, Nacken W, Sorg C, Vogl T, Roth J, Gabrilovich DI. Inhibition of dendritic cell differentiation and accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer is regulated by S100A9 protein. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2235–49. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waight JD, Netherby C, Hensen ML, Miller A, Hu Q, Liu S, Bogner PN, Farren MR, Lee KP, Liu K, Abrams SI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell development is regulated by a STAT/IRF-8 axis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4464–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI68189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poschke I, Mougiakakos D, Hansson J, Masucci GV, Kiessling R. Immature immunosuppressive CD14+HLA-DR-/low cells in melanoma patients are Stat3hi and overexpress CD80, CD83, and DC-sign. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4335–45. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang L, Yi T, Kortylewski M, Pardoll DM, Zeng D, Yu H. IL-17 can promote tumor growth through an IL-6-Stat3 signaling pathway. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1457–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grivennikov SI, Karin M. Dangerous liaisons: STAT3 and NF-kappaB collaboration and crosstalk in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:11–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gupta SC, Sundaram C, Reuter S, Aggarwal BB. Inhibiting NF-kappaB activation by small molecules as a therapeutic strategy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:775–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Condamine T, Gabrilovich DI. Molecular mechanisms regulating myeloid-derived suppressor cell differentiation and function. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'shea JJ, Pesu M, Borie DC, Changelian PS. A new modality for immunosuppression: targeting the JAK/STAT pathway. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:555–64. doi: 10.1038/nrd1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta SC, Prasad S, Reuter S, Kannappan R, Yadav VR, Ravindran J, Hema PS, Chaturvedi MM, Nair M, Aggarwal BB. Modification of cysteine 179 of IkappaBalpha kinase by nimbolide leads to down-regulation of NF-kappaB-regulated cell survival and proliferative proteins and sensitization of tumor cells to chemotherapeutic agents. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:35406–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.161984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]