Summary

This paper reviews the literature examining the relationship between women’s empowerment and contraceptive use, unmet need for contraception and related family planning topics in developing countries. Searches were conducted using PubMed, Popline and Web of Science search engines in May 2013 to examine literature published between January 1990 and December 2012. Among the 46 articles included in the review, the majority were conducted in South Asia (n = 24). Household decision-making (n = 21) and mobility (n = 17) were the most commonly examined domains of women’s empowerment. Findings show that the relationship between empowerment and family planning is complex, with mixed positive and null associations. Consistently positive associations between empowerment and family planning outcomes were found for most family planning outcomes but those investigations represented fewer than two-fifths of the analyses. Current use of contraception was the most commonly studied family planning outcome, examined in more than half the analyses, but reviewed articles showed inconsistent findings. This review provides the first critical synthesis of the literature and assesses existing evidence between women’s empowerment and family planning use.

Introduction

In recent decades, women’s empowerment has emerged as a major theme on the international development agenda (Malhotra et al., 2002). Further, the commitment to improve gender equality and women’s empowerment was reiterated in the Third Millennium Development Goal (MDG3) and in the World Bank’s World Development Report of 2012 as critical factors to improving health and reaching development goals (UN General Assembly, 2000; Kabeer, 2005a).

Women’s empowerment – defined as ‘the expansion of people’s ability to make strategic life choices in a context where this ability was previously denied to them’ (Kabeer, 1999, 2001b) – is increasingly considered a key factor affecting family planning and reproductive health outcomes among women. Central to understanding and supporting women’s ability to make strategic life choices is examining the role of gender-based power as it affects sexual and reproductive health outcomes (Blanc, 2001).

The ability to decide freely the number, spacing and timing of one’s children is a basic human right, endorsed at the International Conference on Population and Development in 1994 (United Nations Population Fund, 1994). Family planning programmes are associated with lower fertility and lower maternal mortality (Cleland et al., 2006). Through family planning programmes, women gain access to contraceptives, increasing the likelihood that they can achieve their desired family size. Yet, despite the well-documented benefits of family planning, an estimated 40% of pregnancies are unintended (Sedgh et al., 2014) and unmet need for contraception remains high despite increased availability of methods (Cleland et al., 2014). Persistent barriers to contraceptive use and related behaviours underscore the need to expand the understanding of, and improve efforts to address, structural drivers of contraceptive use, such as women’s empowerment.

Previous research on women’s empowerment points to its pivotal role in influencing reproductive health behaviours, though there is wide variation in results (Abadian, 1996; Blanc, 2001; Malhotra et al., 2002; Kishor & Subaiya, 2008). A more recent review of women’s empowerment and fertility shows that women’s empowerment is associated with lower fertility, longer birth intervals and lower rates of unintended pregnancy (Upadhyay et al., 2014).

Drawing on a theoretical framework outlined by Blanc, the conceptualization formulated by Kabeer and prevailing assumptions about gender dynamics and reproductive health (Kabeer, 1999, 2001b; Blanc, 2001), it is reasonable to hypothesize that women’s empowerment would be associated with various family planning outcomes. Indeed, it might be expected that as women are more able to make strategic life choices, they might want to plan for the future and expand their life roles beyond being a wife and a mother since using family planning would allow them to delay, space or limit their pregnancies, freeing their time for other pursuits. However, it is essential to periodically scrutinize the evidence regarding such popular assumptions and theories and refine the concepts involved before continuing to develop interventions and programmes, particularly in the context of scarce resources for reproductive health.

The present literature review provides an updated and critical synthesis of the literature, assesses existing evidence, and offers guidance for policies and programmes that address the linkages between women’s empowerment and family planning use.

Methods

The conceptualization of women’s empowerment in this review is based on Kabeer’s definition in which empowerment is defined as the process of having the agency and resources needed to make life choices (Kabeer, 1999). This definition allows a broader conceptualization of women’s empowerment and mirrors the one included in a recent companion review on women’s empowerment and fertility by Upadhyay et al. (2014).

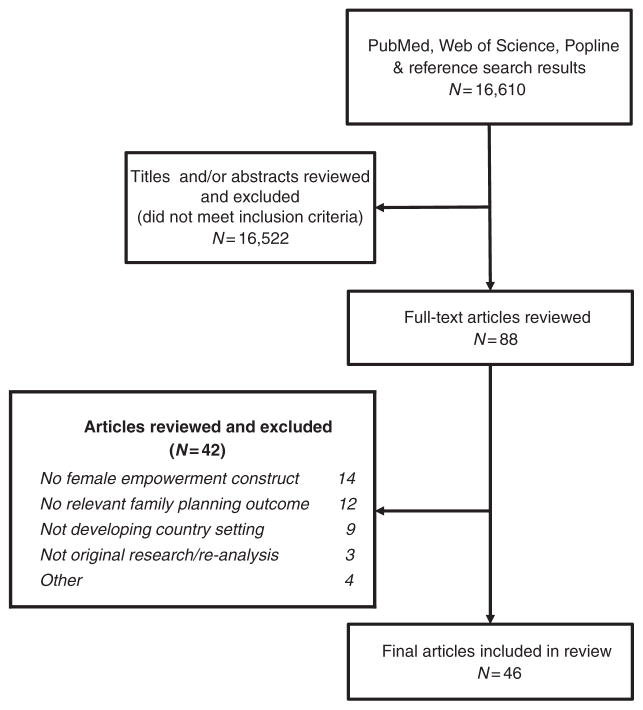

The authors conducted searches using PubMed, Popline and Web of Science search engines in May 2013. The following terms were used alone or in various forms and combinations (and MESH Terms in PubMed): family planning, fertility, family size, ideal family size, contraception, birth spacing, birth intervals, abortion, reproductive health, unintended pregnancy, unplanned pregnancy, parturition, childbearing and number of children, to examine literature published between January 1990 and December 2012. Following this initial search, articles examining only fertility-related outcomes were removed for a separate review (Upadhyay et al., 2014); articles that included contraceptive-use outcomes were retained (see Fig. 1). A hand search of references in key articles supplemented the web-based search, allowing for inclusion of book chapters, reports and other published documents. Titles and abstracts were first reviewed, followed by full-text review of 88 retained articles. The full-text review process excluded 42 articles that did not meet inclusion criteria, leaving 46 articles retained for analysis.

Fig. 1.

Literature review flow chart.

To be included in this review the studies had to: 1) be published in English; 2) use quantitative analysis; 3) use an observational or experimental study design; 4) analyse data from lower- and middle-income countries; 5) examine at least one family planning outcome (current or ever use of family planning, unmet need, future intentions, participation in family planning decision-making, spousal communication regarding family planning (or other fertility and/or household matters) and other related family planning indicators); and 6) examine women’s empowerment as an independent variable and explicitly describe the process used to measure empowerment. Included articles had to either provide a theoretical framework or state the intention to use proxy variables as empowerment constructs. Several outcomes were grouped under other family planning outcomes (e.g. family planning approval, advocacy or knowledge; post-marital family planning use; correct use; effective use of contraception; combined family planning outcomes (multiple outcomes); and contraceptive behaviour composite scores) as detailed in the Results section. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPTF) recommendations were used to assess the quality of the evidence in the studies, based on hierarchy of research design and typology from Type I to III, and a three-level rating system (good, fair, poor) was used to rate the internal validity of each paper (see Table 1) (Harris et al., 2001).

Table 1.

Typology and grade of evidence

| Type of study | Grade | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Type I | Good, Fair, Poor | Evidence obtained from at least one properly randomized controlled trial |

| Type II-1 | Good, Fair, Poor | Evidence obtained from well-designed controlled trials without randomization |

| Type II-2 | Good, Fair, Poor | Evidence obtained from well-designed cohort or case-control analytic studies, preferably from more than one centre or research group |

| Type II-3 | Good, Fair, Poor | Evidence obtained from multiple time series with or without the intervention (dramatic results in uncontrolled experiments could also be regarded as this type of evidence) |

| Type III | Good, Fair, Poor | Opinions of respected authorities, based on clinical experience, descriptive studies and case reports or reports of expert committees |

This hierarchy was copied verbatim (with one parenthetical removed) from Harris et al. (2001).

For each article meeting the inclusion criteria, the authors: 1) identified the empowerment domain(s); 2) graded and tabulated each study based on the type, rating and family planning outcome; and 3) summarized the significance and direction of association between the empowerment domain and the family planning outcome. Studies often analysed more than one family planning outcome measure (i.e. 65 separate outcomes among 46 papers). Therefore, the authors tracked the number of papers that included analyses examining each domain and also tallied the number of analyses conducted per indicator within each domain. Almost all studies presented multivariable analyses with multiple control variables; unadjusted associations (or those with only one control variable; Sathar & Kazi, 1997) were only counted in the rare cases in which no more adjusted results were presented and are highlighted in the Results section as ‘bivariate’ analyses (Sathar & Kazi, 1997; Morgan et al., 2002; Khan et al., 2009; Peyman et al., 2009).

The empowerment domain measures were those explicitly operationalized by the articles’ authors and the level of association was based on analyses presented according to the statistical significance levels specified in the studies. For example, the authors’ conceptualization of empowerment was deferred to, even when they relied on characteristics not typically considered empowerment proxies, such as urban/rural residency and household structure (Isiugo-Abanihe, 1994; Chapagain & Matrika, 2005). Empowerment was measured in a variety of ways: use of single variables (e.g. education), creating summative scales in a single domain (e.g. sum score of household decision-making) and combining variables across different domains to form ‘composite’ empowerment scales. Only a few of the reviewed studies used principal component analysis to create indices of empowerment (e.g. Zafar, 1996; Steele et al., 1998; Woldemicael & Beaujot, 2011). Empowerment domains were considered consistently associated with a family planning outcome if the total number of associations in a certain direction (positive, negative or null) exceeded 60% of the analyses conducted regarding that outcome. Results that were more evenly divided between significant and non-significant were deemed inconsistent.

Results

In total, the 46 reviewed articles incorporated eighteen domains of women’s empowerment (Table 2). The majority of studies (n = 36, 78%) assessed multiple domains. Other domains were based on women’s status as indicated by sociodemographic proxy variables (e.g. education domain: educational attainment and/or literacy), as defined by authors of reviewed articles.

Table 2.

Empowerment domain list

| Domain | Indicator |

|---|---|

| 1. Age | |

| 2. Education | Literacy |

| Years of education | |

| Vocational training pre-marriage | |

| Husband’s education | |

| 3. Occupation type/employment status | Paid employment duration |

| Paid (cash) employment (income) | |

| Worked pre-marriage | |

| Employment outside the home | |

| 4. Household income/wealth | Ownership of assets (Personal) income |

| 5. Urban/rural residence | |

| 6. Household structure | Head of household |

| Nuclear/extended family (marital intimacy) | |

| 7. Household decision-making | Overall weight of opinions/who usually gets their way/final say |

| Decision to seek health care or use medicines for self or family | |

| Decisions regarding children’s marriage/health care/ clothes/education/travel | |

| When and number of children to have or whether to foster | |

| Domestic and children related | |

| Household chores/cooking | |

| House repairs | |

| Management of finances/income | |

| Whether woman works outside home | |

| Who mainly decides spending money you earn | |

| Major/minor household purchases or sales | |

| Purchases of clothes/shoes/jewellery for self | |

| Decision to lease or buy land | |

| Decisions about leisure activities | |

| Socio-cultural and family relations | |

| Supporting/lending to/borrowing from family members (Decisions regarding) visits to friends/relatives | |

| 8. Reproductive decision-making | Reproductive/family planning decisions |

| Main decision-maker on number of children to have or agreement on ideal family size | |

| Overall weight of opinions/who usually gets their way/final say | |

| 9. Sexual decision-making | Can personally refuse husband/partner sex |

| Justifiability of wife beating for refusing sex (when tired/not in mood) or requesting condom when wife knows husband and has a sexually transmitted infection | |

| Sexual empowerment composite score | |

| Sexual and reproductive health. Resources: felt prepared for first sex | |

| Sexual and reproductive health. Resources: heard about sexually transmitted infection pre-martial | |

| Reproductive rights | |

| 10. Mobility/freedom of movement | Travel alone or accompanied |

| Community centre | |

| Fields (around village) | |

| Hospital/health centre | |

| Inside/outside village (next village) | |

| Market/shopping | |

| Neighbours | |

| Political/social meetings | |

| See a movie | |

| Sports ground | |

| Talk to unknown man | |

| Hypothetical right to unaccompanied travel | |

| Visit relatives or friends | |

| With/without permission | |

| Work outside home (as mobility indicator) | |

| 11. Financial autonomy/economic power | Allowed to set money aside |

| Wife has own savings scheme | |

| Personal savings/ownership of gold | |

| Authority to spend money | |

| Decide how to spend money | |

| Freedom to purchase | |

| Any say in major purchases, selling livestock, wife’s working outside the home | |

| Felt free to buy sari or small item of jewellery without permission from other household members | |

| Provided most or over half of family’s support | |

| Respondent has a say in household decision-making | |

| Respondent says she can survive without husband | |

| Can support self and dependants w/out husband | |

| Spending money on household items | |

| Spending women’s extra money | |

| Used her own income for business or money-lending | |

| Who manages family budget | |

| Wife has own income | |

| Worked for income in the last year | |

| Works for cash (and invests) | |

| Wife’s perceived control over family income | |

| Who mainly decides spending money woman earns | |

| Type of work (professional/agriculture) | |

| 12. Marriage or relationship | Age at marriage characteristics |

| Age/education/income/expenditures relative to spouse | |

| Marriage duration | |

| Whether spouse is a blood relative | |

| Ability to choose partner | |

| Husband lived in same area pre-marriage | |

| Husband primary source of social support | |

| Knew husband well/met husband pre-marriage | |

| Relationship power | |

| Egalitarian roles | |

| Partner’s participation in household chores | |

| Type of marriage (monogamous vs polygamous) | |

| Wife rank at marriage (sole, senior, junior) | |

| 13. (Freedom from) control by partner or family | Controlling attire (Freedom from) domination by family members |

| Exposure to actual/threat of physical/psychological/ sexual violence, coercion, abandonment or homelessness | |

| Fear of disagreeing with partner | |

| Money, land, jewellery or livestock taken against her will | |

| Preventing her from visiting natal home or working outside the home | |

| 14. Gender attitudes/beliefs of woman or partner | Son preference |

| Census-based pop status index | |

| Education level desired for sons and daughters | |

| Freedom to establish relationships (husband’s attitudes) | |

| Labour/gender (equity) roles attitudes | |

| Male partner’s responsibility to share domestic and child care work (husband’s attitudes) | |

| Perceived success in role of wife and mother | |

| Who should control the household budget | |

| Who should make decisions | |

| Wife needs husband’s permission to us family planning | |

| Women’s freedom of movement (husband’s attitudes) | |

| Freedom from domestic violence (husband’s attitudes) | |

| Whether husband is justified in beating wife | |

| 15. Exposure to public life | Awareness of political/legal/social activities |

| Campaigned for a political candidate | |

| Exposure to mass media | |

| Joined others to protest | |

| Knowledge of public officials/rights/benefit of marriage registration | |

| Participation in political/legal/social activities and organizations | |

| Participation in a Microfinance Intervention | |

| Radio ownership | |

| 16. Contraceptive, general self-efficacy and family planning knowledge | Ability to meet/get well-planned family health needs/ information |

| Ability to obtained desired option even when opposed | |

| Can and should control sexual and contraceptive situations | |

| Responsibility for direction of sexual activity | |

| Family planning self-efficacy to negotiate condom use among sex workers | |

| Family planning knowledge | |

| 17. Spousal communication | Discuss family planning (and/or fertility) |

| 18. Autonomy/empowerment composite score/scale | Composite empowerment scale/autonomy composite score |

| Composite household decision-making/family planning decision-making, mobility or autonomy |

Nearly three-fifths of the studies were conducted in Asia (n = 26, 57%) (data not shown), 24 of which were from South Asia, including one South and South-East Asia multi-country study (Morgan et al., 2002). This regional skew probably arises because many of the earliest theoretical frameworks were tested in South Asia (Vlassoff, 1982; Dyson & Moore, 1983; Bhatt, 1989). Fewer than one-third of the articles focused on Africa (n = 14, 30%), including one multi-country article (Do & Kurimoto, 2012). A few studies (n = 4, 9%) were from the Middle East. Only one of the included studies focused on Latin America, and one analysed data from countries in multiple regions.

More than three-quarters of the articles (n = 35, 76%) involved currently married women, although a couple of articles sampled ever-married women of reproductive age (Kishor, 1995; Khan, 1997) and a few did not specify marital status (n = 4, 9%) (e.g. Zafar, 1996; Biswas & Kabir, 2002; Ahmed et al., 2010; Bogale et al., 2011). Four studies included couples (Safilios-Rothschild, 1990; Kritz et al., 2000; Chapagain & Matrika, 2005; Haile & Enqueselassie, 2006) and one study included couple–mother-in-law triads (Fikree et al., 2001).

Table 3 displays a citation key, which includes a list of the included articles and the reference tracking number assigned at the beginning of the literature review. Table 4 presents results on the strength of evidence in each article according to the tracking numbers listed in Table 3. The 46 articles investigated a total of 65 family planning outcomes, with 36 papers examining a single family planning outcome (e.g. current use only) and ten papers analysing multiple outcomes (e.g. both current use and future intention to use). Most of the existing evidence comes from Type III studies (descriptive studies) (n = 41, 89%). The few articles that used more rigorous designs (n = 5, 11%) only examined current use of contraception. Most papers (n = 44, 96%) included at least one multivariable analysis, while two provided only bivariate analyses (Chapagain & Matrika, 2005; Ip et al., 2009).

Table 3.

Citation tracking key

Table 4.

Summary of strength of evidence from studies investigating associations between empowerment and family planning (FP) or related outcomes in reviewed articles (N = 46), by level of methological rigour according to USPSTF hierarchy

| Type of study | No. articles per type and grade | FP use | FP needs and intentions | Related FP outcomes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Current use (n = 33) | Ever use (n = 8) | Future FP intentions (n = 6) | Unmet need (n = 2) | FP decisionmaking (n = 3) | Spousal communication (n = 2) | Othera (n = 8) | ||

| Type II-2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 2 | 21; 46 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Fair | 1 | 27 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Poor | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Type II-3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Good | 1 | 61 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Fair | 1 | 41 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Poor | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Type III | 41 | 28 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| Good | 31 | 4; 6; 7; 14; 16; 19; 23; 25; 28; 29; 30; 31; 32; 34; 38; 39; 40; 47; 48; 57; 58; 67; 88 | 3; 24; 30; 34; 35; 57; 65 | 7; 29; 30; 31; 39; 51 | 36; 66 | 25 | 24; 31 | 30; 31; 49; 51; 57 |

| Fair | 7 | 12; 17; 37 | 55 | — | — | 11 | — | 29; 64 |

| Poor | 4 | 10; 54 | — | — | — | 13 | — | 33 |

The overall numbers of articles that include findings related to each family planning outcome are indicated in parentheses. The number of articles within each family planning outcome are listed in bold according to the USPTF typography.

The total number of articles per type and grade exceeds the total number of articles included in the review because one article included different analyses for current and other outcomes, which received different grades.

The article reference numbers, as given in Table 3, are listed in italics according to the grade of evidence assigned during the review of evidence.

Articles include multiple outcomes so total outcomes examined (N = 65) exceed total articles reviewed (N = 46).

Eight articles included analyses for eleven outcomes because one article examined multiple ‘Other Family Planning outcomes’ which were counted separately.

Eighteen studies (39%) presented findings from primary data collection, including seven studies evaluating credit programmes or other interventions. Twelve articles analysed Demographic Health Survey (DHS) data or sub-surveys, e.g. Negotiating Reproductive Outcomes (NRO; DeRose & Ezeh, 2010), and thirteen used national or subnational regional surveys.

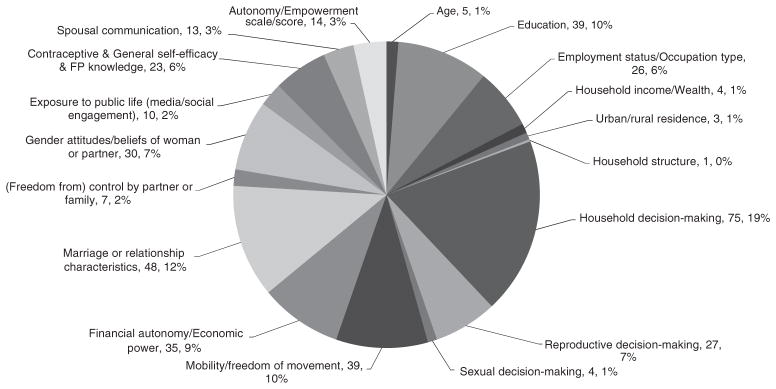

As shown in Fig. 2, certain domains of empowerment were more commonly represented in the analyses than others, including archetypal domains of women’s empowerment (household decision-making and mobility) and classic women’s status proxies (education and employment). Although the proportions of domains in articles versus domains analysed rarely varied by more than 2%, a few notable differences existed. Household decision-making was mentioned in 19% (n = 75) of analyses and 15% (n = 21) of articles. Mobility/freedom of movement was mentioned in 13% (n = 17) of articles, and only 10% (n = 39) of analyses. Marriage or relationship characteristics were in 6% (n = 8) of articles and 12% (n = 48) of analyses.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of all analysis by empowerment domain (N = 433).

Findings by family planning outcome

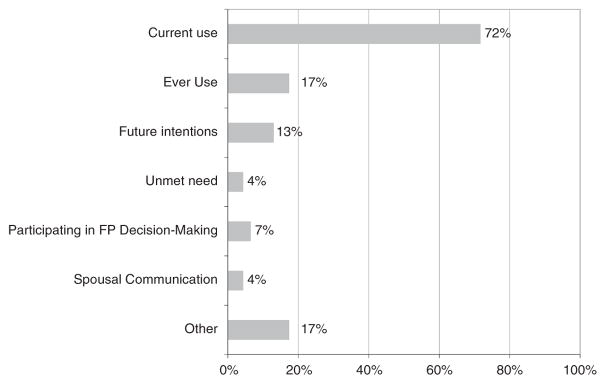

Figure 3 shows the distribution of findings by family planning outcome. Current use of family planning is by far the most studied outcome in relation to women’s empowerment and dominates or nearly dominates all the findings. Tables 5 and 6 present a summary of the findings by empowerment domain and family planning outcome (see Table 3 for citation key).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of articles by family planning outcome (N = 46). Total number of outcomes (N = 65) exceeds the total number of articles as some articles examined multiple outcomes. Other family planning outcomes included eleven outcomes examined in eight articles: family planning knowledge (n = 3 articles), wife’s approval (n = 2 articles), advocacy, correct family planning ‘practice(s)’, effective use of method, contraceptive behaviour scales, fertility control and post-marriage contraceptive use interval (n = 1 articles each).

Table 5.

Summary of findings by empowerment domain and family planning (FP) outcome: articles and associations with current and ever use, intentions and unmet need

| Empowerment domain | References | No. articles | Current use of FP

|

Ever use of FP

|

Future FP intentions

|

Unmet need

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | Null | − | Total | + | Null | − | Total | + | Null | − | Total | + | Null | − | Total | ||||

| 1 | Age | 13; 30 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | Education | 4; 12; 13; 24; 27; 30; 31; 32; 34; 41; 49; 54; 88 | 13 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 15 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | Employment status/ occupation type | 13; 27; 30; 31; 32; 34; 41; 49; 88 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | Household income/wealth | 10; 13; 54 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | Urban/rural residence | 88 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | Household structure | 13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | Household decision-making | 6; 10; 11; 16; 19; 21; 23; 25; 27; 28; 29; 30; 31; 39; 40; 47; 57; 58; 61; 65; 66 | 21 | 9 | 31 | 0 | 40 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 8 | Reproductive decisionmaking | 10; 19; 25; 31; 35; 38; 55; 57 | 8 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 14 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | Sexual decision-making | 14; 49 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | Mobility/freedom of movement | 6; 10; 12; 17; 19; 23; 25; 28; 29; 40; 41; 46; 47; 48; 57; 61; 65 | 17 | 10 | 21 | 2 | 33 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | Financial autonomy/ economic power | 17; 19; 21; 24; 27; 38; 39; 46; 47; 57; 58 | 11 | 11 | 15 | 0 | 26 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | Marriage or relationship characteristics | 24; 27; 29; 30; 31; 49; 64; 88 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 2 | 16 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | (Freedom from) control by partner or family [reverse coded] | 10; 13; 46; 58; 67 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | Gender attitudes/beliefs of woman or partner | 6; 11; 19; 25; 27; 29; 38; 39; 47; 65; 67 | 11 | 9 | 14 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | Exposure to public life (media/social engagement) | 10; 13; 58; 67 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | Contraceptive, general self-efficacy & FP knowledge | 11; 19; 33; 36; 51; 64 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 17 | Spousal communication | 17; 34; 40; 57; 65; 66; 88 | 7 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 18 | Autonomy/empowerment scale/score | 3; 4; 7; 10; 21; 35; 37 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Grand totals | 96 | 122 | 5 | 223 | 31 | 12 | 2 | 45 | 18 | 11 | 2 | 31 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 | |||

Table 6.

Summary of findings by empowerment domain and family planning outcome: articles and associations with decisionmaking, spousal communication and other FP variables

| References | No. articles | FP decisionmaking | Spousal communication | Other FP variables | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| + | Null | − | Total | + | Null | − | Total | + | Null | − | Total | ||||

| 1 | Age | 13; 30 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | Education | 4; 12; 13; 24; 27; 30; 31; 32; 34; 41; 49; 54; 88 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 9 |

| 3 | Employment status/occupation type | 13; 27; 30; 31; 32; 34; 41; 49; 88 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| 4 | Household income/wealth | 10; 13; 54 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | Urban/rural residence | 88 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | Household structure | 13 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | Household decision-making | 6; 10; 11; 16; 19; 21; 23; 25; 27; 28; 29; 30; 31; 39; 40; 47; 57; 58; 61; 65; 66 | 21 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 10 |

| 8 | Reproductive decision-making | 10; 19; 25; 31; 35; 38; 55; 57 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 9 | Sexual decision-making | 14; 49 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 10 | Mobility/freedom of movement | 6; 10; 12; 17; 19; 23; 25; 28; 29; 40; 41; 46; 47; 48; 57; 61; 65 | 17 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 11 | Financial autonomy/economic power | 17; 19; 21; 24; 27; 38; 39; 46; 47; 57; 58 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 12 | Marriage or relationship characteristics | 24; 27; 29; 30; 31; 49; 64; 88 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 0 | 14 |

| 13 | (Freedom from) control by partner or family [reverse coded] | 10; 13; 46; 58; 67 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | Gender attitudes/beliefs of woman or partner | 6; 11; 19; 25; 27; 29; 38; 39; 47; 65; 67 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 15 | Exposure to public life (media/social engagement) | 10; 13; 58; 67 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | Contraceptive & general self-efficacy & FP knowledge | 11; 19; 33; 36; 51; 64 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 10 |

| 17 | Spousal communication | 17; 34; 40; 57; 65; 66; 88 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | Autonomy/empowerment scale/score | 3; 4; 7; 10; 21; 35; 37 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Grand totals | 13 | 10 | 0 | 23 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 14 | 37 | 25 | 0 | 62 | |||

Current use of contraception

Of the 223 analyses between the empowerment domains and current contraceptive use, more than half (n = 122/223) found null results, while significant positive associations were found in fewer than half (n = 96/223) of the analyses. Negative associations were uncommon, found in only five analyses (Table 5). The distribution of analyses of current use among domains was similar to the overall distribution. Studies of empowerment and current contraceptive use relied heavily on two domains: household decision-making (n = 18/33 articles) and mobility (n = 16/33 articles). Surprisingly, analyses found consistently non-significant associations (i.e. at least 60% of the analyses in the same direction) between current contraceptive use and household decision-making indicators (Amin et al., 1995; Govindasamy & Malhotra, 1996; Schuler et al., 1997; Hogan et al., 1999; Hindin, 2000; Fikree et al., 2001; Mahmood, 2002; Moursund & Kravdal, 2003; Hakim et al., 2003; Haile & Enqueselassie, 2006; Feldman et al., 2009; DeRose & Ezeh, 2010; Hamid et al., 2011; Do & Kurimoto, 2012) and mobility (Amin et al., 1995; Steele et al., 1998; Chacko, 2001; Fikree et al., 2001; Biswas & Kabir, 2002; Mahmood, 2002; Morgan et al., 2002; Moursund & Kravdal, 2003; Hakim et al., 2003; Mumtaz & Salway, 2005; Hamid et al., 2011; Do & Kurimoto, 2012). For example, analysis of DHS data in four African countries (Namibia, Zambia, Ghana and Uganda) found no significant associations between household decision-making or mobility and current use of either female- or couple-controlled methods (Do & Kurimoto, 2012).

A smaller proportion of studies reported a mix of positive and null findings for household decision-making (Hogan et al., 1999; Mahmood, 2002; Hakim et al., 2003; DeRose & Ezeh, 2010) and mobility (Biswas & Kabir, 2002; Mahmood, 2002; Moursund & Kravdal, 2003). These mixed results seem to depend on the domain, specific indicator, level of analysis and setting. The construction of scales or use of varied reference categories may have also influenced the associations. For example, for a study in Uganda, DeRose and Ezeh constructed a trichotomous empowerment exposure variable (joint, wife or husband) with joint decision-making as the reference category and used multilevel analyses. They found that individual-level, wife-dominated decisionmaking remained non-significant, while husband-dominated decision-making lost significant positive effects after adjusting for community-level controls (DeRose & Ezeh, 2010). However, only wife-dominated decision-making at the community level was significantly associated with increases in current use of contraception, compared with joint decision-making (p≤ 0.001). In another multi-level study in India, Moursund and Kravdal (2003) found that women’s scores on an individual household decisionmaking scale and on a community decision-making autonomy index were not significantly predictive of contraceptive use in adjusted models. However, when examining a different domain of empowerment, that same model found personal mobility lost its significant positive association with the use of contraception in general, and among those wanting no more children in models adjusted for community-level variables. Moreover, average physical autonomy (a community mobility indicator) was among the rare negative results, inversely associated with current use in general and among women desiring no more children. In a different study, another example of mixed findings, mobility (as indicated by having recently gone out somewhere alone), was not significantly associated with current contraceptive use for rural Pakistani women (Mahmood, 2002). However, the same study found such mobility positively associated with current use for urban women (OR = 1.24, p≤ 0.05), as was the ability to go to a health clinic alone for both urban (OR = 1.22, p ≤0.05) and rural (OR = 1.39, p ≤0.01) women.

Women’s literacy, or her husband’s educational attainment (Isiugo-Abanihe, 1994; Hoque & Murdock, 1997; Hogan et al., 1999; Hindin, 2000; Al Riyami et al., 2004; Kabir et al., 2005), spousal communication about family planning, fertility, finances and/or other household matters (Isiugo-Abanihe, 1994; Dharmalingam & Morgan, 1996; Sathar & Kazi, 1997; Mahmood, 2002; Kabir et al., 2005) and composite empowerment scores (Kishor, 1995; Amin et al., 1996; Biswas & Kabir, 2002; Al Riyami et al., 2004; Feldman et al., 2009) were consistently positively associated with current contraceptive use (in ≥60% of analyses). The findings for women’s employment and gender attitudes were consistently null, whereas the results for financial autonomy were equivocal. For example in Nigeria, Isiugo et al. (1994) found spousal communication was associated with higher odds of current contraceptive use among Igbo women in general (OR = 8.46, p< 0.01), and had an even more dramatic effect on younger women (OR = 12.26, p<0.01) than their older counterparts (OR = 9.05, p<0.01), as compared with those with less spousal communication. In their multi-country study, Do et al. (2012) found women with higher financial autonomy were more likely to use female- (p<0.01) and couple-controlled (p<0.05) contraceptive methods in Uganda, though they found no significant associations in Namibia or for either type of method in Zambia and Ghana.

Among the studies examining the relationships between reproductive or sexual decision-making and current contraceptive use, the majority found consistently positive associations (Govindasamy & Malhotra, 1996; Sathar & Kazi, 1997; Hogan et al., 1999; Kravdal, 2001; Biswas & Kabir, 2002; Do & Kurimoto, 2012), while the lone study on sexual decision-making (based on an index of questions related to refusing sex or requesting condom use) produced mixed positive and null results (Crissman et al., 2012).

In southern Ethiopia, involvement in fertility decisions quadrupled the odds of contraceptive use among rural and urban women (OR 4.00, p≤ 0.05 and OR 4.44, p ≤0.05, respectively) (Hogan et al., 1999). In Egypt, women who preferred to make family planning decisions independently (OR = 1.69, p ≤0.001) or jointly as a couple (OR = 1.67, p≤ 0.001) were more likely to currently use contraception than those who preferred for their husband or others to make such decisions (Govindasamy & Malhotra, 1996). Participation in family planning decision-making was significantly and positively associated with current use in five analyses examining that relationship (Govindasamy & Malhotra, 1996; Sathar & Kazi, 1997; Hogan et al., 1999; Kravdal, 2001; Biswas & Kabir, 2002), but not in three of the four countries included in Do et al.’s (2012) analysis. The latter study found participation in family planning decision-making was not significantly associated with the use of ‘couple’ methods in Namibia, ‘female’ methods in Uganda or either method type in Ghana, although it was positively associated with use of both types in Zambia.

Some empowerment indicators or proxies, such as spousal communication regarding family planning and other matters, marital characteristics and empowerment composite scores, were less frequently examined in the literature (n = 5/33 articles each). Unsurprisingly, spousal communication was significantly associated with current use in all (n = 8/8) analyses conducted on related indicators (Isiugo-Abanihe, 1994; Dharmalingam & Morgan, 1996; Sathar & Kazi, 1997; Mahmood, 2002; Kabir et al., 2005), and empowerment composite scores were consistently positive as well (n = 7/8) (Kishor, 1995; Amin et al., 1996; Biswas & Kabir, 2002; Al Riyami et al., 2004; Feldman et al., 2009). For example, using 1999–2000 Bangladesh DHS data to examine the impact of women’s status on family planning use in Sri Lanka (n = 9696 married women aged 10–49), Kabir et al. (2005) found spousal communication regarding family planning was associated with nearly triple the odds of current use of contraception (OR = 2.8, p <0.001).

Ever use of contraception

The second most studied family planning outcome was ever use of contraception (versus never use) (n = 8/46 articles) (Gage, 1995; Khan, 1997; Sathar & Kazi, 1997; Hindin, 2000; Kabir et al., 2005; Saleem & Pasha, 2008; Woldemicael, 2009; Ahmed et al., 2010) (Table 5). In contrast to the analyses of current use of contraception, those of ever use (n = 45/403 analyses) were more evenly distributed among the notably fewer domains examined (n = 10/18). Most studies relied on multivariable analyses, with the exception of one (Sathar & Kazi, 1997). The majority of the analyses of empowerment and ever use of contraception found positive associations, while around a quarter found null associations; negative associations were rare. More articles focused on education, household decision-making, reproductive decision-making and spousal communication regarding family planning; other domains were examined in only one or two articles.

Women’s empowerment domains consistently positively associated (in ≥60% of analyses) with ever use of contraception were education (Gage, 1995; Hindin, 2000; Kabir et al., 2005), employment (Hindin, 2000; Kabir et al., 2005), household decisionmaking (Hindin, 2000; Woldemicael, 2009), reproductive decision-making (Khan, 1997; Saleem & Pasha, 2008), financial autonomy (Gage, 1995; Sathar & Kazi, 1997), marital characteristics (Gage, 1995; Hindin, 2000), spousal communication (Kabir et al., 2005; Woldemicael, 2009) and empowerment composite scores (Khan, 1997; Ahmed et al., 2010). Mixed findings from one article often contributed to consistently positive associations for domains overall. For example, Gage (1995) found both positive and null associations between education and ever use of family planning. For other domains, such as reproductive decision-making and empowerment composite scores, however, all analyses were positively associated with ever use of contraception. For example, in an analysis of data from the Bangladesh Fertility Survey (1988–89), of 11,905 ever-married women aged 10–50, Khan et al. (1997) found that higher participation in family planning decision-making autonomy was significantly associated with ever use of contraception among both younger and older women in both rural and urban settings.

In an Eritrean study, Woldemicael (2009) found mixed positive and negative associations between women’s empowerment measures and contraceptive use. Specifically, women who reported that wife beating was never justified were less likely (AOR = 0.79, p< 0.05) to have ever used contraception than women who agreed with at least one justification for wife beating. However, the analysis did not appear to adjust for age, an important potential confounder. Other analyses in the same study found Eritrean women in households where final decisions regarding small purchases were made jointly (AOR = 0.51, p< 0.01) or by the husband/others (AOR = 0.55, p< 0.01), or where decisions regarding visiting relatives were made by the husband/others (AOR = 0.75, p <0.10) and those who had never discussed family planning with their husbands (AOR = 0.30, p< 0.01), were all less likely to have ever used contraceptives than women who had the final say in these decisions and those who had discussed family planning with their husbands. As part of their analysis, Woldemicael et al. (2009) also demonstrated that common proxy measures of women’s empowerment, such as education and employment, did not mediate the relationship between empowerment and ever use of contraception in this setting.

Future family planning intentions

Intention to use family planning in the future (compared with not intending to use) was investigated in six reviewed articles, which included indicators from ten domains (Amin et al., 1996; Hogan et al., 1999; Kritz et al., 2000; Hindin, 2000; Peyman et al., 2009; Hamid et al., 2011) (Table 5). Analytical samples in most articles were clearly limited to current non-users, but authors of two articles did not explicitly explain whether the samples excluded current users (Peyman et al., 2009; Hamid et al., 2011). Most analyses of future intentions to use contraception were consistently and positively related to women’s empowerment measures (n = 18/30 analyses), while a third were non-significant (n = 10/30 analyses) and few were negative (n = 2/30 analyses). Two domains – marriage and relationship characteristics (Hogan et al., 1999; Hindin, 2000; Hamid et al., 2011) and household decision-making (Hogan et al., 1999; Hindin, 2000; Kritz et al., 2000; Hamid et al., 2011) – were predominantly examined.

The empowerment domains with consistently positive associations with future intentions to use contraception (in ≥60% of analyses) were education, employment and household decision-making, while marital characteristics were consistently non-significant. For example, Hindin et al. (2000) found wives who had ‘a say’ in household decisions on major purchases (37%, p<0.01), their employment (22%, p<0.10) or any matter (48%, p<0.01) were more likely to intend to use family planning in the future compared with women who did not have a say in such matters. However, having a say in household decisions regarding the number of children was not significantly associated with future family planning intentions. Among the non-significant findings for marital characteristics, the relationships between both spousal relationship indicators (kinship and met prior to marriage) (Hamid et al., 2011) and between age differences between spouses (Hindin, 2000) and intended future contraceptive use were null. The relationship between self-efficacy and future intentions to use contraception was studied in only one paper, which found mixed results (Peyman et al., 2009). Several domains (mobility, autonomy empowerment scale and gender attitudes) included only one analysis each, and two positive associations and one non-significant association were found, respectively.

Unmet need for family planning

Only two reviewed articles investigated the relationship between empowerment and unmet need for contraception (Khan et al., 2009; Woldemicael & Beaujot, 2011) (Table 5). These studies included five analyses (n = 5/403) pertaining to three empowerment domains: household decision-making, self-efficacy and spousal communication. Khan et al.’s (2009) cross-sectional study of pregnancy preferences and unmet need for contraception among sex workers in Madagascar found that low condom negotiation self-efficacy was associated with greater odds of unmet need for contraception (prevalence ratio (PR) = 2.0, 95% CI: 1.4–3.0). In contrast, the study by Woldemicael and Beaujot (2011) found that women with higher reported levels of spousal communication were also more likely to report having an unmet need for contraception (for spacing, OR = 1.41, p< 0.01; for limiting, OR = 1.87, p< 0.01; and overall, OR = 1.50, p <0.05).

Participation in family planning decision-making

While several articles investigated the effects of reproductive decision-making on various family planning outcomes (n = 7/46 articles) (Govindasamy & Malhotra, 1996; Khan, 1997; Hogan et al., 1999; Kravdal, 2001; Biswas & Kabir, 2002; Saleem & Pasha, 2008; Do & Kurimoto, 2012), fewer articles (n = 3/46 articles) investigated the relationship between empowerment and participation in family planning decisionmaking as a dependent variable (n = 23/403 analyses) (Govindasamy & Malhotra, 1996; Chapagain & Matrika, 2005; Bogale et al., 2011) (Table 6). Only Govindasamy and Malhotra (1996) examined participation in family planning decision-making as both an exposure and outcome. The majority of analyses investigating the relationship between empowerment and participation in family planning decision-making as an outcome were positive (n = 13/23 analyses) and some were null (n = 10/23 analyses) with no negative findings. The most consistently positive associations were found for household decisionmaking, freedom from control by partner and gender attitudes. Consistently non-significant associations were found for only one domain of empowerment: exposure to public life. The two papers investigating this decision-making as an outcome did not examine reports of actual participation in family planning decision-making but rather reported the ability to participate in or preferences regarding participation in family planning decision-making (Govindasamy & Malhotra, 1996; Bogale et al., 2011).

Govindasamy and Malhotra (1996) analysed data from the 1988 Egypt Demographic & Health Survey of currently married women (n = 5790) and their preferences for participation in family planning decision-making by the husband/others, the wife primarily or the couple jointly. Women’s perception of ‘the weight of her point of view’ in the household (treated as an indicator of household decision-making), their preference for who should control household finances and their mobility were associated with a higher probability of preferring joint family planning decision-making.

Spousal communication regarding family planning

More than a dozen articles examined spousal communication as a predictor of family planning outcomes (n = 6/46 articles) (Isiugo-Abanihe, 1994; Dharmalingam & Morgan, 1996; Mahmood, 2002; Kabir et al., 2005; Woldemicael, 2009; Woldemicael & Beaujot, 2011). However, the examination of spousal communication as a family planning outcome itself was not common (n = 2/46 articles) (Gage, 1995; Hogan et al., 1999). Of the fourteen analyses on spousal communication, the majority found positive associations (n = 10/14 analyses) and the remaining found null results with no negative associations.

The most commonly studied empowerment domains used in analyses examining spousal communication as an outcome were education (n = 3/14 analyses) (Gage, 1995; Hogan et al., 1999), employment (n = 3/14 analyses) (Hogan et al., 1999) and marital characteristics (n = 5/14 analyses) (Gage, 1995; Hogan et al., 1999). The empowerment domains with the most consistently positive findings were education, occupation and household decision-making. Household wealth was also found to be positive in the only analysis conducted on this indicator. Analyses of marital characteristics and spousal communication found consistently null associations. In a study of autonomy among rural and urban women in southern Ethiopia using 1997 national and regional data, Hogan et al. (1999) found that literacy (OR = 3.37, p≤0.05 and OR = 3.54, p≤0.05, respectively) and involvement in household decision-making (OR = 1.47, p≤0.05 and OR = 1.72, p≤0.05, respectively) were associated with higher levels of spousal communication, but working for cash was only significant for rural women (OR = 1.82, p≤0.05).

Other family-planning-related variables

Several articles (n = 8/46) examined the relationship between women’s empowerment and other family-planning-related outcomes (n = 11 outcomes) (Sathar & Kazi, 1997; Hogan et al., 1999; Hindin, 2000; Wang & Chiou, 2008; Ip et al., 2009; Peyman et al., 2009; Hamid et al., 2011; Pande et al., 2011). These outcomes include: family planning approval, advocacy or knowledge (in general or regarding methods or sources of contraception); post-marital family planning use interval; effective use of contraception; unique combined outcomes, such as ‘fertility control efforts’ (current use and spousal communication) and ‘practice’ (correct use and visiting provider); and scores on constructed ‘contraceptive behaviours’ scales (which were notably non-comparable). Most studies conducted multivariable analyses between empowerment exposures and other family planning outcomes examined, but a few presented some bivariate (Peyman et al., 2009) or only bivariate results (Sathar & Kazi, 1997; Ip et al., 2009). Overall, empowerment was consistently and positively associated with other family planning outcomes, but this varied dramatically by domain and outcome. No negative associations were found.

The most analysed and consistently positive empowerment domains were household decision-making (Sathar & Kazi, 1997; Hogan et al., 1999; Hindin, 2000; Hamid et al., 2011), reproductive decision-making (Hogan et al., 1999) and self-efficacy (Wang & Chiou, 2008; Ip et al. 2009; Peyman et al., 2009). For example, household decisionmaking was positively associated with other family-planning-related outcomes in three studies (Sathar & Kazi, 1997; Hogan et al., 1999; Hindin, 2000). Financial autonomy, examined in fewer analyses, also had consistently positive associations (Sathar & Kazi, 1997). Among the positive findings, Hogan et al. (1999) found rural and urban women in southern Ethiopia with greater involvement in domestic decision-making also had greater knowledge of modern contraceptive methods (OR = 1.94, p ≤0.05 and OR = 1.33, p ≤0.05, respectively) and were more likely to know where to obtain contraceptives (OR = 2.04, p ≤0.05 and OR = 1.47, p ≤0.05, respectively).

More than half the articles (n = 5/8) investigating the other family planning outcomes included analyses of marital characteristics and found consistently null associations (Wang & Chiou, 2008; Hamid et al., 2011; Pande et al., 2011). Two articles examining mobility also found only null associations, as did the one article investigating sexuality decision-making (n = 2/62 analyses of each domain). In contrast, two articles examining the reproductive decision-making domain found completely positive associations. Hamid et al. (2011) found a rare positive association between a women’s marital agency (based on a scale measuring involvement and voice in choosing a spouse) and the interval between marriage and use of contraception among married youth in Pakistan but found a null association for the other two marital empowerment indicators (meeting spouse prior to marriage and kinship with spouse). In contrast, Hogan et al. (1999) found certain marital characteristics were positively associated with empowerment in southern Ethiopia. For example, women married to a man less than 10 years older than her were more likely to know of modern contraceptive methods (rural 29%; urban 35%, p≤ 0.05) or to know a source for obtaining methods (urban 28%, p ≤0.05), as compared with their counterparts with larger spousal age differences (>10 years older than her).

Discussion

The studies included in this review demonstrate that the relationship between women’s empowerment and family planning is complex and depends heavily on the empowerment domain and family planning outcome investigated. Variations in the results depend on the study population and its context, in addition to which empowerment measurement and family planning outcome were used. Empowerment was consistently and positively associated with ever use of contraception, intention to use contraception in the future and outcomes such as spousal communication regarding family planning. Associations between empowerment and current contraceptive use were inconsistent. Consistently positive results for most outcomes and the puzzling mix of significant positive and non-significant associations between empowerment and the much more widely studied outcome, current contraceptive use, raise important methodological issues in terms of conceptualization of empowerment and selection of both indicators and outcomes. These findings also point to potential directions for future research and reveal some limitations of this review.

Selection of appropriate outcome measures

A key consideration in determining the relevance of these reviewed studies to the development of future research and programmatic efforts is a critical assessment of the utility of each outcome. For example, current use, while valuable as a more easily ascertained measure of the factors contributing to women’s ability to access contraception, is limited in most studies by the omission of information on why women were not using contraception at the time of the survey (e.g. not sexually active or pregnant). Only a few studies of current use excluded women who definitely or possibly wanted to become pregnant soon (e.g. Govindasamy & Malhotra, 1996; Crissman et al., 2012). In contrast, focusing on ever use of, or future intentions to use, contraception provides a lifespan perspective, even in cross-sectional studies, and may be especially relevant in the study of empowerment, which hinges on the ‘ability to make strategic life choices’ (Kabeer, 1999). However, these outcomes also have special considerations as they are confounded by the woman’s age, parity and current use of contraception.

The definition of the outcome and the approach to the analysis might explain some non-significant associations or unexpected findings. For example, studies may have failed to detect an association between empowerment and current use because the analyses were limited to women with one child (of a certain age) who wanted to space or limit childbearing, potentially tapping into unmet need (Hindin, 2000; Kravdal, 2001). Studies on empowerment and unmet need in Eritrea also found some inverse association between spousal communication and unmet need (Woldemicael & Beaujot, 2011). However, because unmet need is a constructed outcome based on women’s reports of fertility preferences, as well as current use of contraception, women’s empowerment could very well have disparate and even conflicting effects on the outcomes comprising this measure. For example, women who have or perceive a greater ability to control their fertility may be more likely to state a need for contraception due to a desire for a smaller family size, relative to their peers. However, the ability to enact these preferences through contraceptive use probably hinges on all of the supply-side factors necessary for women to access and use contraception.

Among the less-studied outcomes, the current review highlights two additional family-planning-related outcomes: participation in family planning decision-making and spousal communication. Instead of focusing so heavily on uptake alone, which can be a one-dimensional outcome, the study of empowerment and family planning might benefit from more examination of factors that lead to family planning use. Furthermore, certain relationships between empowerment and important outcomes, such as discontinuation and method satisfaction and switching, are not addressed in the literature at all. There seems to be a tacit assumption that anyone who is currently using, or has ever used, a contraceptive method is empowered enough to continue or resume use as desired. This neglects the possibility of shifting barriers and potentially inconsistent ability to navigate or overcome these barriers, changes in contraceptive access or availability of a preferred method, or changes in spousal agreement regarding additional childbearing (spacing or limiting), any of which might require even more empowerment to surmount.

Selection of appropriate empowerment measures

The conceptualization and measurement of empowerment domains and indicators is as important as the selection and definition of outcome measures. There was a heavy reliance on some domains of empowerment, while others were less utilized. The study of empowerment is challenging because it seeks to capture an elusive latent construct with no strict consensus on its definition. Furthermore, empowerment is culturally defined and constructed. Developing measures to reflect its complexity and multi-dimensionality makes empowerment research all the more daunting. In the face of such challenges, it is not surprising that simple, replicable indicators are sought.

Some domains, such as household decision-making and mobility, may have emerged as the most commonly studied domains in the review literature because they seem to be readily assessed using summative scales and are applicable in a variety of settings. This may be the case for the use of certain proxies, such as education, as well. However, the range and mix of topics aggregated under the household decision-making domain is extensive and variable. Thus, while cross-study comparisons are possible when standardized measures are used, this is less feasible when measures vary across studies. Constructions of empowerment using a variety of domains may reflect the complexity and multi-faceted nature of empowerment itself and/or the inadequacy of existing measures (Upadhyay & Karasek, 2010).

In addition to the selection of indicator domains, the construction of the empowerment variable determines what is probably measured and its comparability as well. For example, DeRose et al. (2010) speculated that they may have found significant results for their analysis of household decision-making and current contraceptive use because, unlike other researchers, they used trichotomous decision-making, with joint decisions as their reference category as opposed to husband-dominated or wife-dominated decisions.

The domination of the evidence base by current use is imposing, with the second most-studied dependent family planning variable, ever use of contraception, studied in only one-fifth as many analyses (or one-quarter as many articles). Research on future intentions to use family planning, the third most commonly studied outcome, was similarly sparse. The value of each of these outcomes would depend on the exposure being studied. Half of the few studies of ever use were conducted in South Asia where mobility is an important construct. However, only two studies investigated mobility and ever use of contraception, perhaps again because mobility is so dependent on the particular age or phase of life (cross-sectional), whereas ever use reflects cumulative experiences over the entire life course and context. Thus, the nature of the outcome variable may point to the appropriate empowerment domains to examine. However, the effect of some empowerment variables, such as self-efficacy, might be especially relevant for intervention on specific outcomes, such as future intentions.

Contradictory findings may depend on the domain of empowerment examined (Woldemicael & Beaujot, 2011). In one analysis, increased empowerment measured by household decision-making was associated with decreased unmet need, while in the same statistical model increased empowerment measured by spousal communication was associated with increased unmet need. This suggests that while empowerment in one domain may be sufficient to generate demand and/or facilitate surmounting barriers to contraceptive use, empowerment in other domains may simply generate demand for contraception without conferring the ability to access and use it.

Some family planning behaviours were examined as empowerment indicators leading to related family planning outcomes or family planning use or future intentions. For example, both spousal communication and participation in family planning decisionmaking were examined in a few studies as empowerment variables. Both are so proximate to other family planning outcomes (namely, use or non-use) that consistent positive associations were expected. However, slightly inconsistent associations were found between participation in family planning decision-making and some family planning outcomes and might point to a disconnect between decision-making and actual use or related contraceptive behaviours.

The use of proxy variables to reflect women’s empowerment has been embraced by some researchers and challenged by others. Several analyses included socioeconomic variables such as education and/or employment status as empowerment proxies or variables potentially mediated by empowerment, notably studied in Oman, Pakistan and Zimbabwe (Hindin, 2000; Al Riyami et al., 2004; Saleem & Pasha, 2008) or as suitable proxies for empowerment, notably in Togo (Gage, 1995). Other studies questioned the adequacy of such variables as proxies and/or the extent of their role as mediators in the relationship between women’s empowerment and reproductive health outcomes (e.g. Dharmalingam & Morgan, 1996; Govindasamy & Malhotra, 1996; Woldemicael, 2009). Future work is needed that incorporates both theoretical and empirical findings into the development of rigorous and, ideally, longitudinal analyses that explore and test the components of women’s status and empowerment in a given setting, the potentially independent and synergistic effects of these components, as well as their causal pathways to reproductive health outcomes.

While a similar proportion of the studies included in the present and companion fertility reviews (Upadhyay et al., 2014) use primary data (37% and 42%, respectively), none of the studies using primary data in this review included locally defined empowerment indicators. This is unfortunate because although use of standardized measures facilitates comparisons among international studies, the use of culturally relevant measures may capture empowerment more accurately (Mumtaz & Salway, 2009) and reveal more meaningful relationships between empowerment and family planning outcomes.

Limitations

This study developed search criteria based on widely accepted conceptualizations of empowerment but may have missed relevant studies that defined empowerment differently. It is possible that the initial triaging of articles, based on title and abstract (a common approach) might have led to the inadvertent exclusion of pertinent articles. However, this approach seemed appropriate given that included articles had to involve a central focus on women’s empowerment and family planning, which should really be apparent in the article’s title and/or abstract. While articles were searched in the most widely used, relevant databases and also hand-searched references, as with all reviews it is possible articles that were not indexed in any of the databases at the time of the search, or which were not well-cited by other reviews or reviewed articles, might have been missed. The exclusion of non-English language papers might explain the identification of so few studies from Latin America and West Africa that would have contributed to theoretical perspectives and the current evidence base. In addition, emphasis on breadth over depth limited the possibility of discussion of studies’ specifics or more complex dynamics in this review. Lastly, positive publication bias may also play a limiting role in this review. Most studies included multiple empowerment indicators and found at least one positive association, which were usually heavily emphasized by authors. Non-significant associations were less common overall but such null findings were typically understated. Furthermore, few studies with solely non-significant findings or results showing unexpected (inverse) associations were identified (e.g. Chacko, 2001).

Study design issues for future research

Beyond issues related to the selection of appropriate dependent and independent variables, the authors identified additional issues related to the evidence base and study design for consideration in future research, but also the need for additional research in general. The published companion review of empowerment and fertility (Upadhyay et al., 2014) identified 24% more papers (n = 60) than this review (n = 46) focusing on family planning. Given that family planning has a pivotal impact on fertility outcomes it seems more research is warranted.

The extant literature regarding empowerment and family planning is heavily skewed towards studies conducted in South Asia. Gender equity is a major issue in South Asia but the empowerment and status of women in other regions, like East Asia, Latin America and Africa, merit investigation as well. It is difficult to draw comparisons across studies globally with such a narrow geographic range and to gain insight into unique context-specific dynamics that might only be relevant in certain regions (e.g. mobility in Asia, polygamy/wife rank in Africa).

Studies focused largely on contraceptive use among married women although a few included ever-married women. Very few studies involved unmarried women, a trend that would ideally be reversed in subsequent studies, given that early sexual initiation and later childbearing is occurring throughout the world. It should be noted that future studies of family planning and contraceptive behaviours that include unmarried women would need to develop conceptualizations of empowerment that are applicable regardless of household role or family composition (e.g. do not rely on husband–wife decision-making).

It is difficult to obtain a full picture of complex dynamics from an individual-level perspective alone, yet very few studies investigated couple data, the role of men and community-level factors. For example, given that women’s empowerment could be considered relative to, and seen to a great extent to be dependent on, prevailing cultural context or social systems, the predominant focus on individual-level factors and limited studies of community-level factors may account for the lack of a consistent association in the evidence. Furthermore, due to differences in the role of men in family planning decision-making in different settings, women may not need as much autonomy or empowerment to use contraception to fulfil their fertility desires in settings where family planning is normative. Findings from such settings would attenuate results from settings where the level of women’s autonomy or power has a more primary influence on family planning outcomes (S. Schuler, personal communication). Additionally, very few studies address interventions that might directly or indirectly affect factors that might mediate the relationship between women’s empowerment and family planning. In this review, interventions mostly involved credit or income-generating programmes (Gage, 1995; Amin et al. 1996; Schuler et al., 1997; Steele et al., 1998) and some have found positive impact (Amin et al., 1996). However, some evaluations and reviews of credit programmes call into question the findings or indirect claims of the impact of such interventions on family planning outcomes, often noting that these credit programmes attract women who may already have high levels of empowerment (e.g. Pitt et al., 1999; Kabeer, 2001a, 2005b).

Most reviewed studies were cross-sectional, which does not allow causality to be inferred. Due to the lack of studies employing more rigorous designs, the quality of the evidence, even with some strong multivariate associations based on observation data, is relatively weak overall. Measurement of empowerment remains challenging, but improved conceptualization and more rigorous research may further elucidate the dynamics involved. Given that two of the domains of empowerment identified in this review were also regarded as family planning outcomes, it seems likely that engaging in other family planning behaviours, such as using contraceptive methods, serves as an empowering experience. Empowerment is a process (Malhotra et al., 2002) and, as such, is suited to longitudinal studies to capture women’s experiences and to pinpoint the causal factors and mediating variables involved. Adding to the complexity of these linkages, a woman’s status, empowerment and/or autonomy, along with her contraceptive knowledge, attitudes and practices, probably evolve and interact over her life course (Lee-Rife, 2010).

Conclusions

The success of global development efforts hinge on improving the status of women and girls (Klugman et al., 2014). Efforts to promote reproductive rights within a human rights framework and allow women to control their fertility will only have limited success unless women’s individual resources and skill sets are expanded and the broader context in which they are operating is taken into account. While empowering women to control their fertility has been an on-going and daunting challenge, it is crucial to resist the urge to treat women’s empowerment as a magic bullet (Kabeer, 2005b) or as one-size-fits-all solution (Do & Kurimoto, 2012). Instead, in the context of scarce resources, it is important to measure the process, identify factors amenable to intervention and bring any transferrable interventions to scale. To that end, more research using rigorous methods and innovative approaches should be conducted to lay the foundation for the implementation of evidence-based solutions. This review synthesizes the available quantitative evidence on the relationships between women’s empowerment and family planning, highlights methodological challenges and points to important considerations for future research of empowerment domains. As global development efforts increase their focus on women’s empowerment, this assessment can contribute to researchers and programme planners’ current efforts.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the University of California Global Health Institute (UCGHI) Women’s Health and Empowerment Center of Expertise. Ndola Prata and Ashley Fraser’s participation was supported by the Bixby Center for Population, Health and Sustainability, University of California, Berkeley. Megan Huchko’s participation was supported by UCSF-CTSI Grant Number KL2 RR024130. Jessica Gipson’s participation was supported by NIH Grant #1K01HD067677. Shayna Lewis’ work on this paper was initiated while she was at the Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH) program at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Erica Ciaraldi’s participation was supported by the Bixby Center on Population and Reproductive Health in the Fielding School of Public Health. Ushma Upadhyay’s participation was supported by ANSIRH program at UCSF and NIH Grant #1K01HD077064-01A1. The authors thank Stephanie Blount, supported by the UC Berkeley Bixby Center, for assistance with initial literature searches and Emma Roos-Collins, a UC Berkeley Bixby Center Senior Intern, for assistance in final manuscript preparation.

References

- Abadian S. Women’s autonomy and its impact on fertility. World Development. 1996;24(12):1793–1809. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Creanga AA, Gillespie DG, Tsui AO. Economic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Riyami A, Afifi M, Mabry RM. Women’s autonomy, education and employment in Oman and their influence on contraceptive use. Reproductive Health Matters. 2004;12(23):144–154. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(04)23113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin R, Hill RB, Li Y. Poor women’s participation in credit-based self-employment: the impact on their empowerment, fertility, contraceptive use, and fertility desire in rural Bangladesh. Pakistan Development Review. 1995;34:93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Amin R, Li YP, Ahmed AU. Women’s credit programs and family planning in rural Bangladesh. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1996;22(4):158–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt E. Toward empowerment. World Development. 1989;17(7):1059–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas TK, Kabir M. Women’s empowerment and current use of contraception in Bangladesh. Asia-Pacific Journal of Rural Development. 2002;12(2):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc AK. The effect of power in sexual relationships on sexual and reproductive health: an examination of the evidence. Studies in Family Planning. 2001;32(3):189–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogale B, Wondafrash M, Tilahun T, Girma E. Married women’s decision making power on modern contraceptive use in urban and rural southern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:342. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacko E. Women’s use of contraception in rural India: a village-level study. Health & Place. 2001;7(3):197–208. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(01)00009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapagain M, Matrika C. Masculine interest behind high prevalence of female contraceptive methods in rural Nepal. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2005;13(1):35–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1854.2004.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland J, Bernstein S, Ezeh A, Faundes A, Glasier A, Innis J. Sexual and reproductive health 3 - Family planning: the unfinished agenda. Lancet. 2006;368(9549):1810–1827. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland J, Harbison S, Shah IH. Unmet need for contraception: issues and challenges. Studies in Family Planning. 2014;45(2):105–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crissman HP, Adanu RM, Harlow SD. Women’s sexual empowerment and contraceptive use in Ghana. Studies in Family Planning. 2012;43(3):201–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRose LF, Ezeh AC. Decision-making patterns and contraceptive use: evidence from Uganda. Population Research and Policy Review. 2010;29(3):423–439. [Google Scholar]

- Dharmalingam A, Morgan SP. Women’s work, autonomy, and birth control: evidence from two South Indian villages. Population Studies. 1996;50(2):187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Do M, Kurimoto N. Women’s empowerment and choice of contraceptive methods in selected African countries. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2012;38(1):23–33. doi: 10.1363/3802312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson T, Moore M. On kinship structure, female autonomy, and demographic behavior in India. Population and Development Review. 1983;9(1):35–60. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman BS, Zaslavsky AM, Ezzati M, Peterson KE, Mitchell M. Contraceptive use, birth spacing, and autonomy: an analysis of the Oportunidades program in rural Mexico. Studies in Family Planning. 2009;40(1):51–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2009.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fikree FF, Khan A, Kadir MM, Sajan F, Rahbar MH. What influences contraceptive use among young women in urban squatter settlements of Karachi, Pakistan? International Family Planning Perspectives. 2001;27(3):130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Gage AJ. Women’s socioeconomic position and contraceptive behavior in Togo. Studies in Family Planning. 1995;26(5):264–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindasamy P, Malhotra A. Women’s position and family planning in Egypt. Studies in Family Planning. 1996;27(6):328–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haile A, Enqueselassie F. Influence of women’s autonomy on couple’s contraception use in Jimma town, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development. 2006;20(3):145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim A, Salway S, Mumtaz Z. Women’s autonomy and uptake of contraception in Pakistan. Asia Pacific Population Journal. 2003;18(1):63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid S, Stephenson R, Rubenson B. Marriage decision making, spousal communication, and reproductive health among married youth in Pakistan. Global Health Action. 2011;4:5079. doi: 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, Lohr KN, Mulrow CD, Teutsch SM, Atkins D. Current methods of the US Preventive Services Task Force – a review of the process. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;20(3):21–35. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindin M. Women’s autonomy, women’s status and fertility-related behavior in Zimbabwe. Population Research and Policy Review. 2000;19(3):255–282. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DP, Berhanu B, Hailemariam A. Household organization, women’s autonomy, and contraceptive behavior in southern Ethiopia. Studies in Family Planning. 1999;30(4):302–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.1999.t01-2-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]