Abstract

Objectives

Refugees in Uganda come from HIV-afflicted countries, and many remain in refugee settlements for over a decade. Our objective was to evaluate the HIV care cascade and assess correlates of linkage to care.

Methods

We prospectively enrolled individuals accessing clinic-based HIV testing in Nakivale Refugee Settlement from March 2013-July 2014. Newly HIV-diagnosed clients were followed for three months post-diagnosis. Clients underwent a baseline survey. The following outcomes were obtained from HIV clinic registers in Nakivale: clinic attendance (“linkage to HIV care”), CD4 testing, antiretroviral therapy (ART) eligibility, and ART initiation within 90 days of testing. Descriptive data were reported as frequencies with 95% confidence interval (CI) or medians with interquartile range (IQR). The impact of baseline variables on linkage to care was assessed with logistic regression models.

Results

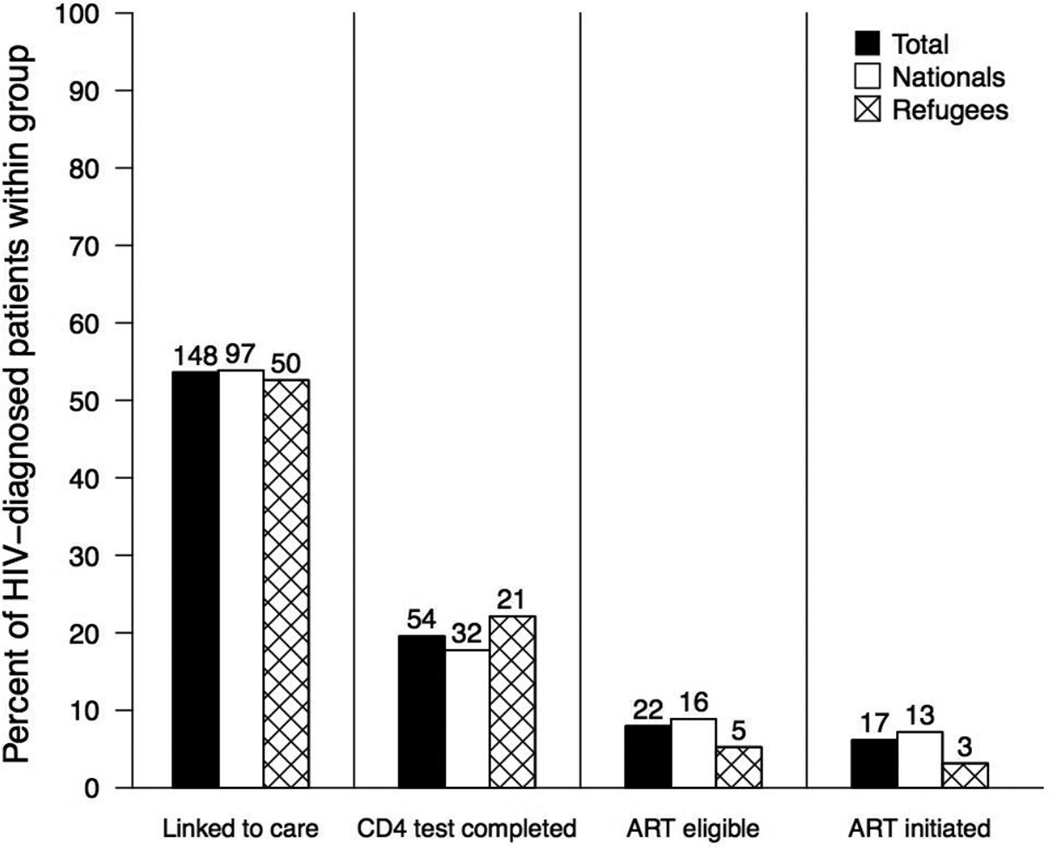

Of 6,850 adult clients tested for HIV, 276 (4%; CI 3–5%) were diagnosed with HIV, 148 (54%; CI 47–60%) of those linked to HIV care, 54 (20%; CI 15–25%) had a CD4 test, 22 (8%; CI 5–12%) were eligible for ART, and 17 (6%; CI 3–10%) initiated ART. The proportions of refugees and nationals at each step of the cascade were similar. We identified no significant predictors of linkage to care.

Conclusions

Less than a quarter of newly HIV-diagnosed clients completed ART assessment, considerably lower than other reports from sub-Saharan Africa. Understanding which factors hinder linkage and engagement in care in the settlement will be important to inform interventions specific for this environment.

Keywords: HIV, refugee, care continuum, cascade of care, sub-Saharan Africa

INTRODUCTION

HIV prevalence among the 2.9 million refugees and asylum-seekers in sub-Saharan Africa is largely unknown (1). Refugees suffer numerous hardships unique to their history: accessing basic needs, disrupted social networks, limited livelihood opportunities, frequent threats to their security, and prolonged displacement lasting on average 17 years (2–4). These hardships may increase their vulnerability to HIV infection through more frequent sexual violence and transactional sex, and difficulty accessing condoms and treatment for sexually transmitted infections (2).

Studies in general populations demonstrate attrition along the HIV cascade of care from testing, to attending HIV clinic (“linking to HIV care”), to assessment of antiretroviral therapy (ART) eligibility, to ART initiation, and ultimately to retention in HIV care and sustained virologic suppression (5, 6). A systematic review in sub-Saharan Africa estimated that 57% of HIV-diagnosed people completed ART-eligibility assessment, reflecting the step beyond linkage to care (7). Two reviews in sub-Saharan Arica found that among those who linked to HIV care, retention in care at 24 months averaged 62 and 77% (8, 9).

The HIV care continuum has not been characterized in refugee settlements. However, given the hardships faced in this setting, it is likely that linkage to care is a problem and attrition along the HIV care cascade in this context is as high as it is in the surrounding areas of sub-Saharan Africa, if not higher. Additionally, reasons for poor engagement in HIV care in this setting are likely to be unique to the refugee settlement context, as has been shown in research on barriers to HIV testing (3). We prospectively assessed the HIV care cascade for a cohort of newly HIV-diagnosed refugees and Ugandan nationals in Nakivale Refugee Settlement in southwestern Uganda.

METHODS

Study Site

Uganda has over 350,000 refugees from various countries in sub-Saharan Africa (10). Nakivale Refugee Settlement, established in 1960, hosts 68,000 refugees from 11 countries and is 71 square miles (11). The refugees are largely from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (52%), Somalia (17%), Burundi (15%), and Rwanda (15%) (11). Additionally, Ugandan nationals live in and around Nakivale and access health services in the settlement.

We established a routine clinic-based HIV testing program at the Nakivale Health Center that began March 14, 2013 (12). This site is operated by the non-governmental organization Medical Teams International (MTI). HIV testing is free and uses serial rapid HIV tests outlined in the Uganda HIV Rapid Test Algorithm (13). Newly HIV-diagnosed participants are encouraged to attend HIV clinic, and if willing, are introduced to the HIV clinic counselor immediately following their diagnosis. The Nakivale Health Center laboratory is equipped with two functioning Alere Pima CD4 Analyser machines. ART is free for eligible clients (initiated at CD4 ≤ 350/µL or WHO Stage III/IV based on 2010 WHO guidelines (14)). Clients who are ART-ineligible are provided co-trimoxazole prophylaxis (15). Three satellite clinics throughout the settlement offer free HIV testing and HIV clinic services. As Nakivale Refugee Settlement is in a rural setting, at the time of this research, there were no other accessible HIV clinics within close proximity to the settlement.

Study Design

We prospectively evaluated newly HIV-diagnosed clients from March 14, 2013 until July 11, 2014. Eligibility criteria included being 18 years or older, able to provide informed consent (in English, Kinyarwanda, Kiswahili, or Runyankore), and not known to be HIV-infected. We longitudinally followed this cohort, accessing laboratory and HIV clinic registers at Nakivale Health Center and the three satellite clinics in the settlement approximately twice monthly.

Data Elements

Prior to receiving their HIV test result, clients underwent a baseline survey during HIV testing to gather demographic and socioeconomic data. Information obtained included refugee versus national status, country of origin, years in the settlement, and time spent traveling to clinic. Data elements collected during follow-up at the clinical sites included linkage to HIV care (at least one visit to HIV clinic), CD4 results, ART eligibility, and ART initiation for eligible clients. For our primary analysis, we considered only those events that occurred within 90 days of HIV diagnosis. We performed a secondary analysis of “ever linked” to care by eliminating the time constraint.

This study was approved by the Republic of Uganda Office of the Prime Minister. Ethics committee approvals included: the Makerere University College of Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (Kampala, Uganda), the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (Kampala, Uganda), and the Partners Human Research Committee (Boston, MA, USA; 2012-P-000839).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data were reported as frequencies with an exact (Clopper-Pearson) 95% confidence interval (CI) or medians with interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. For each step of the care cascade, we used Fisher’s exact tests to determine whether the proportion of refugees differed from the proportion of Ugandan nationals; we considered both the proportion among all HIV-diagnosed clients and among only clients who met criteria for the previous step in the cascade. To assess the impact of baseline variables on whether patients linked to HIV care, we used logistic regression models. Variables were considered for inclusion in the multivariate model if the univariate screening p-value was less than 0.25, and were ultimately included in the multivariate model if adjusted p-value was less than 0.05. Two-tailed p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA) and R version 3.1.1 (www.r-project.org).

RESULTS

During the 19-month study period, 6,850 adult clients tested for HIV. Of those tested, 3,517 (51%; CI 50–53%) were female; 4,746 (70%; CI 68–71%) were refugees; and the median age was 28 years (IQR 22–37). Of clients tested, 276 (4%; CI 3–5%) were newly HIV-diagnosed. Ugandan nationals had an HIV-positivity rate of 9% (CI 7–10%). Among refugees, proportions of HIV positivity varied by country of origin (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, Clients HIV-tested and proportion HIV-diagnosed by country of origin). Of the newly HIV-diagnosed participants, 175 (63%; CI 57–70%) were female; 95 (35%; CI 28–41%) were refugees; and the median age was 30 years (IQR 24–38). Of HIV-diagnosed participants, 62% said they live within Nakivale Refugee Settlement and 32% reported they lived in the settlement for <5 years. Additionally, of HIV-diagnosed participants, 61% were married, 67% had not completed primary school, and 54% traveled >1 hour to clinic.

Of the 276 newly HIV-diagnosed clients, 148 (54%; CI 47–60%) linked to HIV clinic in the settlement and 54 (20% of HIV-diagnosed; CI 15–25%) had a CD4 test performed, both within 90 days. The median CD4 was 442/µL (IQR 273–621/µl) for all clients tested within 90 days. Median CD4 counts for refugees (465/µL, n=21) and Ugandan nationals (350/µL, n=32) were not significantly different (p = 0.13). Based on guidelines of ART eligibility with CD4 count of ≤350/µL alone (14), 22 (8% of HIV-diagnosed; CI 5–12%; 41% of those with a CD4 test; CI 27–55%) were eligible for ART. 17 (6% of HIV-diagnosed; CI 3–10%) initiated ART within 90 days of diagnosis; 3 were refugees, 13 were Ugandans, and 1 did not report a nationality (Figure 1). The proportions of nationals and refugees at each step of the cascade of care were not significantly different (all p-values >0.05).

Figure 1.

Cascade of care within 90 days of routine HIV testing at Nakivale Health Center.

Note: One HIV-diagnosed patient did not report refugee status.

No potential predictors of linkage to care were found to be statistically significant in the logistic regression model (Table 1). Although age category was marginally significant (p = 0.07), further assessment using several different models (e.g. age as a categorical, continuous, or ordinal variable) did not result in a statistically significant association of age with linkage.

Table 1.

Predictors of linkage to care within 90 days of routine HIV testing among HIV-diagnosed clients.

| Variable | All HIV- diagnosed (N=276) % (n/N) |

Not linked to care (N=128) % (n/N) |

Linked to care (N=148) % (n/N) |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 63% (175/276) | 67% (86/128) | 60% (89/148) | 0.23 |

| Age (years) | 0.07 | |||

| <30 | 49% (134/276) | 50% (64/128) | 47% (70/148) | |

| 30 to <40 | 30% (82/276) | 35% (44/128) | 26% (38/148) | |

| 40 to <50 | 15% (42/276) | 9% (12/128) | 20% (30/148) | |

| ≥ 50 | 6% (18/276) | 6% (8/128) | 7% (10/148) | |

| Refugee | 35% (95/275) | 35% (45/128) | 34% (50/147) | 0.84 |

| Country of origin | 0.75 | |||

| Uganda (national) | 66% (177/268) | 65% (83/127) | 67% (94/141) | |

| Rwanda | 17% (46/268) | 17% (21/127) | 18% (25/141) | |

| DRC | 9% (23/268) | 8% (10/127) | 9% (13/141) | |

| Burundi | 4% (12/268) | 6% (8/127) | 3% (4/141) | |

| Other† | 4% (10/268) | 4% (5/127) | 3% (5/141) | |

| Live in Nakivale | 62% (168/269) | 62% (79/127) | 63% (89/142) | 0.94 |

| Years living in Nakivale | 0.74 | |||

| <5 | 32% (74/234) | 30% (34/113) | 33% (40/121) | |

| ≥5 | 25% (59/234) | 27% (31/113) | 23% (28/121) | |

| Do not live in Nakivale | 43% (101/234) | 43% (48/113) | 44% (53/121) | |

| Relationship status | 0.67 | |||

| Currently married | 61% (164/269) | 59% (75/127) | 63% (89/142) | |

| Single (never married) | 14% (36/269) | 17% (21/127) | 11% (15/142) | |

| Divorced/Separated | 18% (49/269) | 18% (23/127) | 18% (26/142) | |

| Widowed | 6% (17/269) | 5% (7/127) | 7% (10/142) | |

| Not married, living with partner | 1% (3/269) | 1% (1/127) | 1% (2/142) | |

| Education | 0.78 | |||

| No school | 19% (53/269) | 20% (26/127) | 19% (27/142) | |

| Some primary school | 47% (126/269) | 45% (57/127) | 48% (69/142) | |

| Completed primary school | 17% (45/269) | 16% (20/127) | 18% (25/142) | |

| Higher than primary school‡ | 17% (45/269) | 19% (24/127) | 15% (21/142) | |

| Knowledge questionnaire all correct§ | 39% (106/269) | 40% (51/127) | 39% (55/142) | 0.81 |

| Previous test for HIV | 66% (178/268) | 70% (88/126) | 63% (90/142) | 0.26 |

| More than 1 hour to clinic | 54% (144/269) | 54% (69/127) | 53% (75/142) | 0.80 |

Abbreviations: DRC: Democratic Republic of the Congo

P-value based on univariate logistic regression.

Other includes Tanzania (N=5), Ethiopia (N=3), Senegal (N=1), and Sudan (N=1).

Includes some/completed secondary school, vocational school, certificate program, bachelors, and post graduate.

Questionnaire included 4 questions [correct answer]: (1) Do you think that a healthy-looking person can be infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS? [Yes]; (2) Can a person get HIV by sharing a meal with someone who is infected? [No]; (3) Can a pregnant woman infected with HIV or AIDS transmit the virus to her unborn child? [Yes]; (4) Can a woman with HIV or AIDS transmit the virus to her newborn child through breastfeeding? [Yes].

Removing the 90 day time cut-off and evaluating if the 276 newly HIV-diagnosed clients “ever linked” to HIV care resulted in 28 additional patients linking to care, bringing the total to 176 (64% CI 57–70%). Among the 28 who linked past 90 days, the median time to link to care was 151 days (maximum of 429).

DISCUSSION

Among people accessing HIV testing services at Nakivale Health Center, only half linked to HIV care and less than a quarter had a CD4 test within 90 days of their initial test. We were unable to determine predictors of linkage, and thus the best interventions to improve linkage remain an important area of research. As thousands of refugees and millions of nationals access HIV services in similar settings in sub-Saharan Africa, these data reflect a much larger problem across the region.

We found greater attrition along the HIV care cascade in Nakivale compared to those previously reported for sub-Saharan Africa (7). While more linked to HIV clinic when assessing this information without a time cut-off, there remained considerable attrition. There was a particularly steep drop-off between those who linked to care and those who had a CD4 test. Clinicians in the settlement might have been using WHO clinical classifications rather than CD4 test results to determine ART eligibility (14). It is also possible that the CD4 machines were not functioning or there could have been a lack of CD4 machine supplies resulting in less testing. However, given the surprisingly low number of clients initiated on ART, it is more likely that a large portion of clients did not complete ART eligibility assessment.

While we intended our routine HIV testing program to reach refugees, there were unanticipated benefits for Ugandan nationals (3). Though refugees accounted for 70% of the HIV testing participants, they only accounted for 35% of those HIV-diagnosed. Refugees had a lower risk of HIV infection than nationals, a finding previously demonstrated among other refugee populations (16). Further, HIV-diagnosed refugee participants had a trend toward presenting with less advanced disease with median CD4 counts higher than that of Ugandan nationals (465/µL compared to 350/µL, p=0.13). It may be that nationals at high risk for infection travel further to test for HIV to minimize stigma from their community. Intimate contact with Ugandan nationals testing in Nakivale could put refugees at higher baseline risk of HIV.

Though the factors assessed in the baseline survey did not correlate with linkage to HIV care, more nuanced factors specific to this unique setting could have a measurable impact. For instance, the languages and cultures represented by the refugees are distinct from those of the Ugandan health staff. This may cause refugees to mistrust the healthcare system (17). Additionally, severe poverty and limited land access may impact choices related to health care engagement. It may also be that refugees and Ugandan nationals accessing services in the refugee settlement moved away from their community because of stigma and discrimination. Lack of social support could hinder their successful engagement in HIV care (18, 19). Alternatively, the nationals could be a mobile population, a lifestyle which may interfere with long-term medical care and may yield higher risk sexual behavior and higher rates of HIV transmission (20).

These data should be considered in view of some limitations. Data on country of origin was provided by the participants and was not verifiable. Given political implications refugees face based on their country of origin, some may have falsified information. As our follow-up procedure was to abstract data from clinics in Nakivale, we could not discern if clients enrolled in care outside the settlement. However, given the distance to clinics outside the settlement, we think this was unlikely. Further, our methods did not enable us to track participant death. Additionally, refugee populations differ from one another based on the country of origin, the distribution of the population in terms of age and gender, and the size of the population. Therefore, these findings must be interpreted with caution when extrapolating to other settings.

We found poor linkage to HIV care and considerable attrition along the HIV care continuum for refugees and Ugandan nationals in Nakivale Refugee Settlement. The reasons for poor linkage assessed in this study did not demonstrate an association. As such, we must expand our evaluation and assess factors specific to the refugee settlement context. Future research on linkage to HIV clinical care among refugee populations should assess potential individual factors (i.e. mental health, substance abuse, migration patterns, competing needs), social environment factors (i.e. HIV stigma, social support), physical environment factors (i.e. location of the settlement, transportation availability, food distribution sites), and policies and regulations (i.e. land use policies, security environment); all of these complex issues that may influence health service utilization in this unique population. This assessment may help in designing interventions to improve health service utilization in this setting. Enhancing linkage to HIV care and minimizing attrition for refugees and nationals accessing services in refugee settlements will improve the health of this multinational population and may help us move closer to achieving the UNAIDS 90-90-90 goal among this population (21).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (NIH/NIAID 5P30AI060354) to KNO, the Harvard Global Health Institute to KNO, the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases (R01 AI058736) to KNO, RAP, RPW and IVB and (P30 AI060354) to DJR and RAP. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other funders. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) tools hosted at Harvard University.

The authors appreciate the hard work and dedication of the study research assistants: Kamaganju Stella, Mbabazi Jane, and Muhongayire Bernadette. We also thank the Medical Teams International leadership, the health staff at Nakivale Health Center, and collaborators from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Uganda and Switzerland. We appreciate the support of the Refugee Desk Office and the Office of the Prime Minister of Uganda. We are grateful to the refugee and Ugandan study participants.

Footnotes

For the remaining authors, no conflicts were declared.

KNO, IVB, RPW and RAP conceived and designed the study. JK, SD, ZMF, and EM helped ensure the study was appropriate for the local context and for the refugee settlement environment. JK and EM advised on study implementation. KNO and ZMF supervised data collection and management of data. KEG assisted with evaluating ongoing data collection processes at the study site. DJR analyzed the data with RAP serving as senior advisor providing guidance and supervision of the analysis. KNO drafted the manuscript. KNO, DJR and RAP worked together to create the figure and table. IVB and RPW assisted with in-depth revisions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and offered additional edits. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Kelli N. O’Laughlin, Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Medical Practice Evaluation Center, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Julius Kasozi, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Representation in Uganda, Kampala, Uganda.

Dustin J. Rabideau, MGH Biostatistics Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Robert A. Parker, Medical Practice Evaluation Center, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Division of General Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), Boston, Massachusetts, USA; MGH Biostatistics Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Edgar Mulogo, Department of Community Health, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Mbarara, Uganda.

Zikama M. Faustin, Bugema University, Kasese Campus, Kampala, Uganda.

Kelsy E. Greenwald, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Sathyanarayanan Doraiswamy, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Geneva, Switzerland.

Rochelle P. Walensky, Medical Practice Evaluation Center, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Division of Infectious Disease, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Division of General Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Division of Infectious Disease, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Ingrid V. Bassett, Medical Practice Evaluation Center, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Division of Infectious Disease, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Division of General Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNHCR. Overview of the refugee situation in Africa: Background paper for the high-level segment of the 65th session of the Executive Committee of the High Commissioner's Programme on "Enhancing International Cooperation, Solidarity, Local Capacities and Humanitarian Action for Refugees in Africa". [cited 2016 July 13];2014 Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/54227c4b9.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS and UNHCR. Strategies to support the HIV related needs of refugees and host populations. [cited 2016 July 13];2005 Available from: http://data.unaids.org/publications/irc-pub06/jc1157-refugees_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Laughlin KN, Rouhani SA, Faustin ZM, Ware NC. Testing experiences of HIV positive refugees in Nakivale Refugee Settlement in Uganda: informing interventions to encourage priority shifting. Conflict and health. 2013;7(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-7-2. PubMed PMID: 23409807. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3645965. Epub February 14, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Women's Refugee Commission. Building livelihoods: a field manual for practitioners in humanitarian settings. [cited 2016 July 13];2009 Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/4af181066.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mugglin C, Estill J, Wandeler G, Bender N, Egger M, Gsponer T, et al. Loss to programme between HIV diagnosis and initiation of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tropical medicine & international health : TM & IH. 2012 Sep 20;17(12):1509–1520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03089.x. PubMed PMID: 22994151. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3895621. Epub 2012/09/22. Eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011 Mar 15;52(6):793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. PubMed PMID: 21367734. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3106261. Epub 2011/03/04. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kranzer K, Govindasamy D, Ford N, Johnston V, Lawn SD. Quantifying and addressing losses along the continuum of care for people living with HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2012;15(2):17383. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.2.17383. PubMed PMID: 23199799. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3503237. Epub 2012/12/04. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosen S, Fox MP, Gill CJ. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS medicine. 2007 Oct 16;4(10):e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040298. PubMed PMID: 17941716. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2020494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox MP, Rosen S. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to three years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007–2009: systematic review. Tropical medicine & international health : TM & IH. 2010 Jun;15(Suppl 1):1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02508.x. PubMed PMID: 20586956. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2948795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.UNHCR. 2015 UNHCR country operations profile - Uganda. [cited 2016 July 13];2015 Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e483c06.html. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakivale Population Statistics as of 30-05-2014. Personal communication: UNHCR. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Laughlin KN, Kasozi J, Walensky RP, Parker RA, Faustin ZM, Doraiswamy S, et al. Clinic-based routine voluntary HIV testing in a refugee settlement in Uganda. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2014 Aug 26;67(4):409–413. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000317. PubMed PMID: 25162817. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4213244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ugandan Ministry of Health. Uganda national policy guidelines for HIV counselling and testing. [cited 2016 July 13];2005 Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/uganda_art.pdf.

- 14.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents: Recommendations for a public health approach 2010 revision. [cited 2016 July 13];2010 Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599764_eng.pdf. [PubMed]

- 15.Ugandan Ministry of Health. National antiretroviral treatment guidelines for adults, adolescents, and children. [cited 2016 July 13];2009 Available from: http://www.idi-makerere.com/docs/guidelines%202009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spiegel PB, Bennedsen AR, Claass J, Bruns L, Patterson N, Yiweza D, et al. Prevalence of HIV infection in conflict-affected and displaced people in seven sub-Saharan African countries: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007 Jun 30;369(9580):2187–2195. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61015-0. PubMed PMID: 17604801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen J. Tranforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zachariah R, Teck R, Buhendwa L, Fitzerland M, Labana S, Chinji C, et al. Community support is associated with better antiretroviral treatment outcomes in a resource-limited rural district in Malawi. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2007;101(1):79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watt MH, Maman S, Earp JA, Eng E, Setel PW, Golin CE, et al. "It's all the time in my mind": facilitators of adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a Tanzanian setting. Social science & medicine. 2009 May;68(10):1793–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.037. PubMed PMID: 19328609. Epub 2009/03/31. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lurie MN, Williams BG. Migration and Health in Southern Africa: 100 years and still circulating. Health psychology and behavioral medicine. 2014 Jan 1;2(1):34–40. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2013.866898. PubMed PMID: 24653964. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3956074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.UNAIDS. 90-90-90 An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. [cited 2016 July 13];2014 Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]