Abstract

Poaceae represent the most important group of crops susceptible to abiotic stress. This large family of monocotyledonous plants, commonly known as grasses, counts several important cultivated species, namely wheat (Triticum aestivum), rice (Oryza sativa), maize (Zea mays), and barley (Hordeum vulgare). These crops, notably, show different behaviors under abiotic stress conditions: wheat and rice are considered sensitive, showing serious yield reduction upon water scarcity and soil salinity, while barley presents a natural drought and salt tolerance. During the green revolution (1940–1960), cereal breeding was very successful in developing high-yield crops varieties; however, these cultivars were maximized for highest yield under optimal conditions, and did not present suitable traits for tolerance under unfavorable conditions. The improvement of crop abiotic stress tolerance requires a deep knowledge of the phenomena underlying tolerance, to devise novel approaches and decipher the key components of agricultural production systems. Approaches to improve food production combining both enhanced water use efficiency (WUE) and acceptable yields are critical to create a sustainable agriculture in the future. This paper analyzes the latest results on abiotic stress tolerance in Poaceae. In particular, the focus will be directed toward various aspects of water deprivation and salinity response efficiency in Poaceae. Aspects related to cell wall metabolism will be covered, given the importance of the plant cell wall in sensing environmental constraints and in mediating a response; the role of silicon (Si), an important element for monocots' normal growth and development, will also be discussed, since it activates a broad-spectrum response to different exogenous stresses. Perspectives valorizing studies on landraces conclude the survey, as they help identify key traits for breeding purposes.

Keywords: drought stress, salinity, G6PDH, cell wall, silicon, Hordeum vulgare, Triticum aestivum, Oryza sativa

Introduction

One of the most impelling global challenges is the provision of enough food worldwide. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has indeed estimated a dramatic increase in need for food by 2050 (Cobb et al., 2013). Agriculture represents the main source of global food and plant breeders need to discern the potential improvement of traits in order to increase the yields (Tester and Langridge, 2010). The urgent request of an increase in food production is not easy to achieve even in a stable and optimal agricultural environment; moreover, this scenario is rapidly worsening, because of different factors, such as, the increase of land- and water-use for biofuel-crops, climate change and abiotic stresses (Ruggiero et al., 2017).

Abiotic stresses induce a wide range of molecular, biochemical and physiological alterations in plants, including enhanced accumulation of osmolytes, reduced photosynthesis, stomata closure and the induction of stress-responsive genes (Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki, 2006; Lata et al., 2015).

Water scarcity and soil salinity undoubtedly represent the major limiting factors for plant cultivation and crop productivity (Hayashi and Murata, 1998; Reynolds and Tuberosa, 2008), as they trigger oxidative, osmotic and temperature stresses. Drought, heat and salt stress cause dehydration, which in its turn results in cytosolic and vacuolar volume reduction (Bartels and Sunkar, 2005). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are also produced, which provoke damages to proteins, DNA and membranes (Gill and Tuteja, 2010). Some of the most critical further damages induced by these stresses are: reduction in photosynthesis rate and efficiency, wilting and induction of programmed death cell.

Many other factors play a considerable role in drought and salt stress responses, e.g., SOS (Salt Overly Sensitive) pathway, kinases, phosphatases, abscisic acid (ABA), ion transporters, transcription factors (Lata and Prasad, 2011; Lata et al., 2011), but they will not be discussed in detail in this review, as they have been already extensively treated in previous works.

The role of Poaceae in worldwide food demand is critical: rice is the most important food source for more than half of the world population, (Cui Y. et al., 2016) wheat provides nearly 55% of carbohydrates worldwide (Gill et al., 2004), barley is the fourth most important cereal crop in terms of planting area, mainly used in brewing industries and as forage (Shen et al., 2016).

The natural resistance of barley to exogenous stresses makes it the most tolerant among Poaceae and an important model in stress physiology (Gürel et al., 2016; Shen et al., 2016). Nonetheless, several high-yield H. vulgare cultivars have become sensitive to abiotic stress by loss of genetic variation induced by breeding programs; hence, the response to exogenous constraints has become an important issue in barley as well (Ahmed et al., 2013).

Climate changes between 1980 and 2008 caused a significant yield loss in different crops, including Poaceae: rice showed a remarkable yield reduction in China and in developing countries; the global production of maize and wheat decreased by 3.8 and 5.5%, respectively (Lobell et al., 2011). These data highlight the importance of studies addressing stress physiology in Poaceae and the need to conceive strategies improving specific traits under unfavorable conditions for these economically important crops.

In the present study we will provide an overview of the latest advances in the field of Poaceae stress physiology by focusing, specifically, on drought and salt stress.

Stress-responsive genes in Poaceae: insights from ROS scavengers and water use efficiency-related genes

One of the key mechanisms increasing the adaptation to adverse environmental conditions in plants is the regulation of the reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels (Gill and Tuteja, 2010).

Recently, several abiotic stress-related genes conferring tolerance in Poaceae have been described (key representatives are summarized in Table 1).

Table 1.

List of genes conferring abiotic stress tolerance in Poaceae.

| Gene | Annotation | Function | Stress | Overexpression/inactivation | Species | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G6PDH | Glucose-6P dehydrogenase | NADPH provision | Salt | Overexpression | H. vulgare | Cardi et al., 2015 |

| HVA1 | LEA protein | Enhanced water use efficiency | Drought | Overexpression | H. vulgare | Gürel et al., 2016 |

| HvPIP2;5 | Plasma membrane intrinsic protein 2;5 | Acquaporin | Salt and Osmotic | Overexpression | H. vulgare | Alavilli et al., 2016 |

| OsNAC9 | NAC domain containing protein 9 | Enhanced Uptake in roots | Drought | Overexpression | O. sativa | Redillas et al., 2012 |

| OsASR5 | Abscissic acid and ripening protein 5 | Regulation of stomatal closure and chaperon-like protein | Drought | Overexpression | O. sativa | Li et al., 2016 |

| OsJRL | Jacalin-related lectin | Cell protection and signal transduction | Salt | Overexpression | O. sativa | He X. et al., 2016 |

| OsMYB55 | MYB transcription factor 55 | Modulating expression of drought related genes | Drought | Overexpression | O. sativa | Casaretto et al., 2016 |

| OsNAC2 | NAC domain containing protein 2 | Reduction of LEA and SAPK expression | Drought | Inactivation | O. sativa | Shen et al., 2017 |

| OsPEX11 | Peroxisomal biogenesis factor 11 | Regulation in Na+/K+ transporter, reduction in ROS accumulation | Salt | Overexpression | O. sativa | Cui P. et al., 2016 |

| OsSAP1 | Stress associated protein 1 | Increase root growth and fresh weight | Drought and Salt | Overexpression | O. sativa | Kothari et al., 2016 |

| OsSGL | Stress tolerance and grain length protein | Increase osmolytes accumulation and root growth | Drought | Overexpression | O. sativa | Cui Y. et al., 2016 |

| OsVPE3 | Vacuolar processing enzyme 3 | Vacuole-mediated PCD, Stomatal development | Salt | Inactivation | O. sativa | Lu et al., 2016 |

| TaCRT1 | Calreticulin | Enhanced ROS scavenging activation | Salt | Overexpression | T. aestivum | Xiang et al., 2015 |

| TaGBF1 | G-box binding factor | Induced hypersensivity to salt stress | Salt | Inactivation | T. aestivum | Sun et al., 2015 |

| TaFER-5B | Ferritin | Reduction in ROS accumulation | Drought and Heat | Overexpression | T. aestivum | Zang et al., 2017 |

| TaMYB31 | MYB transcription factor 31 | Cuticle synthesis | Drought | Overexpression | T. aestivum | Bi et al., 2016 |

| TaMYB74 | MYB transcription factor 74 | Cuticle synthesis | Drought | Overexpression | T. aestivum | Bi et al., 2016 |

| TaWRKY1 | WRKY transcription factor 1 | Promoted root growth | Drought | Overexpression | T. aestivum | He G. H. et al., 2016 |

| TaWRKY33 | WRKY transcription factor 33 | Promoted root growth | Drought | Overexpression | T. aestivum | He G. H. et al., 2016 |

| TdMnSOD | Superoxide dismutase | Enhanced ROS scavenging action | Drought and Salt | Overexpression | T. turgidum | Kaouthar et al., 2016 |

| ZmABA2 | Dehydrogenase/ reductase SDR | Regulation of ABA content | Drought | Overexpression | Z. mays | Ma F. et al., 2016 |

| ZmGOLS2 | Galactinol synthase | Raffinose synthesis | Drought and Salt | Overexpression | Z. mays | Gu et al., 2016 |

| ZmMPK5 | MAP kinase 5 | Regulation of ABA content | Drought | Overexpression | Z. mays | Ma F. et al., 2016 |

| ZmPP2C-A10 | Protein phosphatase 2C | Negative controller of ABA pathway | Drought | Inactivation | Z. mays | Xiang et al., 2016 |

The gene names, annotation, function, type of stress, species and references are indicated. Overexpression or inactivation of the specific genes conferring tolerance are indicated.

The manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD) of Triticum turgidum (TdMnSOD) expressed in Arabidopsis thaliana enhanced the tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses by promoting proline accumulation and lowering H2O2 content (Kaouthar et al., 2016). Similarly, tobacco overexpressing the T. aestivum calreticulin protein 1 (CRT1, which plays important roles in Ca2+ signaling and protein folding) showed an enhanced salt tolerance with respect to wild type plants (Xiang et al., 2015).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) must be regulated by enhancing ROS scavenging and/or reinforcing pathways preventing their dangerous increase. In this respect, ferritin gene expression is known to be induced in response to drought, salinity and other stresses (Ravet et al., 2009): Arabidopsis ferritin genes were indeed upregulated by H2O2, iron and ABA. Zang et al. (2017) recently described the interesting potential of T. aestivum ferritin: A. thaliana plants transformed with TaFER-5B and overexpressing transgenic wheat plants showed a lower accumulation of and H2O2, resulting in enhanced heat and drought stress tolerance. These results also demonstrate that monocot genes can confer increased resistance to stresses when heterologously expressed in dicots.

Significant improvements in abiotic stress tolerance by ROS detoxification were obtained also in rice (Oryza sativa—Os). OsSGL (Stress tolerance and Grain Length) codes for a putative DUF1645 domain-containing protein: A. thaliana plants transformed with OsSGL and overexpressing rice plants showed enhanced drought and osmotic stress tolerance (Cui Y. et al., 2016). Additionally, RNA-Seq on rice plants overexpressing OsSGL highlighted an increase in expression of several stress-responsive genes; among these, a number of peroxidases were identified, thereby correlating the OsSGL action with an enhanced ROS scavenging system.

More recently, we have suggested an emerging role in salt and drought stress response for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH–EC 1.1.1.49) (Cardi et al., 2015; Esposito, 2016; Landi et al., 2016). This enzyme catalyzes the oxidation of glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) and the corresponding reduction of NADP+ to NADPH. The increase in G6PDH activity in barley upon salt stress resulted in an increased NADPH production, able to confer stress resistance through the synthesis of osmolytes (e.g., glycine betaine) and ROS scavengers, such as, glutathione (Cardi et al., 2015). This response, notably, is linked to an ABA-dependent pathway (Cardi et al., 2011; Dal Santo et al., 2012).

Another important parameter in the response of crops to dehydration and osmotic imbalances is Water Use Efficiency (WUE). This condition is connected with a decreased photosynthetic rate, plant growth and productivity; usually higher WUE values result in lower stomata conductance (Ruggiero et al., 2017).

Root architecture plays a critical role in WUE in cereals and this is controlled by a number of transcription factors (TFs). The overexpression of the NAC-domain-containing TF OsNAC9 induced drought tolerance in rice transgenic plants, and triggered the formation of an enlarged stele and aerenchyma (Redillas et al., 2012). WRKY is another class of TFs inducing drought tolerance by root modification. The complete WRKY set of T. aestivum has been described (He G. H. et al., 2016): among them, TaWRKY1 and TaWRKY33 were identified as drought-related factors, and used to induce tolerance to Arabidopsis transgenic lines by promoting germination and root growth.

An increased WUE can also be obtained by stimulating wax deposition in the cuticle. In this respect, promising evidences in wheat have been recently obtained using TaMYB31 and TaMYB74 (Bi et al., 2016), two drought-responsive TFs involved in cuticle biosynthesis. When overexpressed transiently in wheat cells using particle bombardment, these TFs were able to activate the promoters of those genes involved in cuticle biosynthesis (Bi et al., 2016): therefore these transcriptional regulators can be used to increase WUE in monocots under drought.

TFs, particularly master regulators, are able to modulate entire pathways (clear examples come from TFs involved in secondary cell wall or suberin deposition; Nakano et al., 2015; Legay et al., 2016), therefore they represent useful candidates for more efficient biotechnological strategies.

ROS scavenging and WUE efficiency are connected by a number of ABA-related genes involved in transduction and transcription pathways. Examples of genes inducing abiotic stress tolerance in Poaceae are OsASR5, ZmASR1, ZmABA2, ZmMPK5: it was demonstrated that these genes connect the regulation of stomatal closure with the antioxidant response and ABA signaling (Virlouvet et al., 2011; Li et al., 2016; Ma F. et al., 2016).

Furthermore, in Poaceae, specific TFs and water channels play a crucial role in the response to abiotic stress: transgenic maize overexpressing the ZmMYB55 showed an increase in drought and heat stress tolerance by reducing ROS levels and lipid peroxidation (Casaretto et al., 2016). Similarly, A. thaliana plants overexpressing the H. vulgare aquaporin HvPIP2; 5 (PIP: Plasma-membrane Intrinsic Protein) revealed an improved tolerance to salt, drought and osmotic stresses (Alavilli et al., 2016). Intriguingly, these genes were co-expressed together with ROS antioxidant enzymes as SOD, catalase (CAT) and ascorbate peroxidase (APX).

The role of cell wall-related genes in Poaceae stress physiology

Cell wall is a natural biocomposite of polysaccharides, proteins and, in certain cases, of the aromatic macromolecule lignin (Guerriero et al., 2014b, 2016b). It is an active structure which partakes in crucial stages of plant development and in cell signaling under exogenous stresses (Parrotta et al., 2015). A specific system of sensors ensures indeed the perception of the cell wall integrity status, which becomes perturbed upon i.e. pathogen attack or abiotic stresses (Gall et al., 2015; Hamann, 2015). Besides the cell wall integrity status perception, plants modulate cell wall-related processes in the presence of exogenous constraints (Guerriero et al., 2014a; Behr et al., 2015): an emblematical example is the deposition of stress lignins upon the sensing of exterior constraints (Moura et al., 2010). Nowadays, thanks to next generation sequencing (NGS), huge dataset are generated which can help shed light on the dynamics of cell wall-related genes in different species. In this paragraph we provide an example using O. sativa as a model, for which the entire genome sequence is available (International Rice Genome Sequencing Project, 2005). We used the rice expression database at http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/expression.shtml, in order to get an overview of salt and drought responsive cell wall-related genes in this important crop (Ouyang et al., 2007). Drought and salt stress treatments in rice (cv. Nipponbare) induced 551 and 1,600 genes in leaves and roots, respectively. In the stress-repressed category, 323 and 613 genes were observed in leaves and roots, respectively. Among these, a significant number of genes belonging to the GO categories “cell wall” (GO: 005618) was found (details are in Table 2). Specifically, 13 and 31 stress-induced and 2 and 41 stress-repressed genes were found in roots and leaves, respectively. Therefore, cell wall remodeling represents a common mechanism in abiotic stress response: plant cell walls are often modified upon drought and salt stress (Tenhaken, 2015). Indeed, wheat cultivars differing in drought stress tolerance were shown to display a different regulation of cell wall-related processes (Leucci et al., 2008).

Table 2.

List of drought- and salt-responsive genes in O. sativa.

| Gene | Induced | Type of stress |

|---|---|---|

| LEAVES | ||

| LOC_Os05g25640.1 | Cytochrome P450 | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os01g11010.1 | Peptide-N4-asparagine amidase A | Drought |

| LOC_Os01g11760.1 | GDSL-like lipase/acylhydrolase | Drought |

| LOC_Os01g33420.1 | Glycosyl hydrolase family protein 27 | Drought |

| LOC_Os11g06390.1 | Actin | Drought |

| LOC_Os11g29190.1 | 40S Ribosomal protein S5 | Drought |

| LOC_Os02g09940.1 | Peroxiredoxin | Drought |

| LOC_Os04g46390.2 | Chaperone protein dnaJ | Drought |

| LOC_Os08g02230.1 | FAD-binding and arabino-lactone oxidase domains containing protein | Drought |

| LOC_Os11g47760.1 | DnaK family protein | Salt |

| LOC_Os12g38170.1 | Osmotin | Salt |

| LOC_Os04g03796.1 | OsSub37 - Subtilisin homolog | Salt |

| LOC_Os07g38760.1 | HEAT repeat family protein | Salt |

| ROOTS | ||

| LOC_Os01g07910.1 | NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase | Drought |

| LOC_Os01g10950.1 | Peptide-N4-asparagine amidase A | Drought |

| LOC_Os01g71670.1 | Glycosyl hydrolases family 17 | Drought |

| LOC_Os11g24450.1 | Mitochondrial carrier protein | Drought |

| LOC_Os12g05040.6 | Heavy-metal-associated domain-containing protein | Drought |

| LOC_Os12g12850.1 | ATP-dependent Clp protease ATP-binding subunit clpA homolog | Drought |

| LOC_Os02g02410.1 | DnaK family protein | Drought |

| LOC_Os02g02400.1 | Catalase isozyme A | Drought |

| LOC_Os02g18650.1 | Pectinesterase | Drought |

| LOC_Os02g44590.1 | OsSub20 - Subtilisin homolog | Drought |

| LOC_Os03g11410.1 | MItochondrial-processing peptidase subunit | Drought |

| LOC_Os03g15690.1 | Phosphate carrier protein mitochondrial precursor | Drought |

| LOC_Os03g15020.1 | Beta-galactosidase precursor | Drought |

| LOC_Os03g49600.1 | Os3bglu7 - beta-glucosidase exo-beta-glucanase | Drought |

| LOC_Os03g55110.1 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 10 | Drought |

| LOC_Os04g41740.1 | Expressed protein | Drought |

| LOC_Os04g44410.1 | OsSCP25 - Serine Carboxypeptidase homolog | Drought |

| LOC_Os04g46390.2 | Chaperone protein dnaJ | Drought |

| LOC_Os04g56930.1 | Glycosyl hydrolases GH32 | Drought |

| LOC_Os05g29790.1 | Pectinesterase | Drought |

| LOC_Os06g40600.1 | Elongation factor | Drought |

| LOC_Os06g48650.2 | OsSub52 - Subtilisin homolog | Drought |

| LOC_Os07g38730.1 | Tubulin/FtsZ domain containing protein | Drought |

| LOC_Os07g44780.1 | GDSL-like lipase/acylhydrolase | Drought |

| LOC_Os08g39500.1 | 60S ribosomal protein L31 | Drought |

| LOC_Os08g39140.1 | Heat shock protein | Drought |

| LOC_Os01g22010.3 | S-adenosylmethionine synthetase | Salt |

| LOC_Os10g33140.1 | hcrVf2 protein | Salt |

| LOC_Os11g03400.1 | Ribosomal protein | Salt |

| LOC_Os02g10070.2 | Citrate synthase | Salt |

| LOC_Os09g25910.1 | Xylanase inhibitor | Salt |

| Gene | Repressed | Type of stress |

| LEAVES | ||

| LOC_Os12g02310.1 | LTPL11 - Protease inhibitor/seed storage/LTP family | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os07g04240.1 | Succinate dehydrogenase flavoprotein | Drought and Salt |

| ROOTS | ||

| LOC_Os01g01060.1 | 40S Ribosomal protein S5 | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os01g05490.1 | Triosephosphate isomerase cytosolic | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os01g18170.1 | Cupin domain containing protein | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os01g28450.1 | SCP-like extracellular protein | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os01g54620.1 | CESA4 - cellulose synthase | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os01g67240.1 | Formin-like protein 1 precursor | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os01g68324.3 | Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide–protein glycosyl transferase 63 kDa | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os01g71060.1 | Xylanase inhibitor | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os10g11500.1 | SCP-like extracellular protein | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os10g25400.1 | GDSL-like lipase/acylhydrolase | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os10g26680.1 | Pectinesterase | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os11g06390.1 | Actin | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os12g21798.1 | 40S ribosomal protein S3a | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os12g32986.1 | Heat shock protein | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os12g38180.1 | Heat shock cognate 70 kDa protein 2 | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os02g18550.1 | 40S ribosomal protein S3a | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os02g44490.1 | Anthranilate phosphoribosyltransferase | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os02g51970.1 | Phosphate-induced protein 1 conserved region domain | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os03g10340.1 | 40S ribosomal protein S3a | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os03g16860.1 | DnaK family protein | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os03g31510.1 | Cysteine proteinase inhibitor 8 precursor | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os03g51440.1 | LRR receptor-like protein kinase | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os03g51600.1 | Tubulin/FtsZ domain containing protein | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os03g53800.3 | Periplasmic beta-glucosidase precursor | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os04g24220.1 | OsWAK32 - OsWAK receptor-like protein kinase | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os04g35090.1 | 40S ribosomal protein S10 | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os04g49690.1 | FERONIA receptor-like kinase | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os04g51460.1 | Glycosyl hydrolases family 16 | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os04g59260.1 | Peroxidase precursor | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os05g04470.1 | Peroxidase precursor | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os05g27940.1 | 40S ribosomal protein S7 | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os05g32110.1 | COBRA | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os05g45950.1 | Outer mitochondrial membrane porin | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os05g48900.1 | Fasc|Iclin domain containing protein | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os07g04240.1 | Succinate dehydrogenase flavoprotein subunit mitochondrial precursor | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os07g48030.1 | Peroxidase precursor | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os07g48060.1 | Peroxidase precursor | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os08g23180.1 | Fasciclin-like arabinogalactan protein 8 precursor | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os08g37840.1 | Phosphate-induced protein 1 conserved region domain containing prot. | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os09g26920.1 | OsSub57 - Subtilisin homolog | Drought and Salt |

| LOC_Os09g31486.1 | DnaK family protein | Drought and Salt |

Particularly interesting is the presence of cell wall receptors among the class of genes downregulated in rice roots (Table 2): the downregulation of OsWAK32 and the ortholog of FERONIA is likely related with the inhibition in root elongation observed upon drought/salt stress in rice.

A number of peroxidase (LOC_Os04g59260.1, LOC_Os05g04470.1, LOC_Os07g48030.1, LOC_Os07g48060.1 e.g.,) were found as repressed in roots of rice (Table 2). Cell wall peroxidases play contradicting roles in abiotic stress response. As example, drought tolerant wheat cultivars exposed to osmotic stress showed higher transcripts levels of the peroxidases TaPrx01, TaPrx03, TaPrx04 (Csiszár et al., 2012). On the other hand, an increase in peroxidase activity may induce the excess in OH− levels, inducing cell wall loosening (Tenhaken, 2015), thus suggesting that a correct balance of peroxidase activities is desirable in abiotic stress tolerance.

Another interesting class of cell wall-related genes regulated by drought and salt stress is represented by pectinesterases (LOC_Os02g18650.1; LOC_Os10g26680.1 e.g.,). Various crops such as, wheat, soybean, tomato, showed higher levels of pectin remodeling enzymes in tolerant cultivars than susceptible genotypes (Leucci et al., 2008; An et al., 2014; Iovieno et al., 2016).

In this respect it should be noted that a study centered on rice identified the presence of methyl esterified pectins in both primary and secondary cell walls and the differential expression of pectin methylesterases upon stress treatments (Jeong et al., 2015).

In rice the role of genes encoding both hydrolytic enzymes and glycosyltransferases can be analyzed via publicly available databases, notably the Rice GH and GT databases (Cao et al., 2008, 2010; Sharma et al., 2013).

Notably, GHs represent an important group of cell-wall related enzymes involved in the remodeling of the cell wall structure, particularly under stress: as expected, at least two GH genes are activated under drought (LOC_Os01g71670.1; LOC_Os04g56930.1) in rice roots, while another gene (LOC_Os04g51460.1) is repressed by drought and salt stress (Table 2).

The expression pattern of cell wall-related genes in rice, as well as other monocots, helps in the identification of specific trends in response to exogenous stresses shared between the dicot and monocot lineages. Houston et al. (2016) made a detailed survey of the microarray data available for Arabidopsis and barley and highlighted those genes coding for CAZymes (Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes) upregulated in both Arabidopsis and barley in response to biotic and abiotic stress. The analyses revealed members of families GT1, GT8, GT61, GT75 (the role of GTs in response to exogenous stresses is less understood than that of GHs) as being upregulated in both organisms in response to the stresses.

Silicon: a crucial element for Poaceae and a stress reliever

Silicon (Si) is an abundant element in soils and it plays an important role in plants, improving vigor, productivity and stress resistance. Si (taken up by plants as silicic acid) acts as a priming agent and activates the defense response arsenal of plants, by stimulating the metabolism, both primary and secondary, via still not fully understood mechanisms (recently reviewed by Guerriero et al., 2016a). Since among Poaceae there are representatives classified as high Si-accumulators (notably the commelinoid monocot rice, which can accumulate up to 10% of the shoot dry weight; Ma et al., 2002) and given its role in boosting the plant response to exogenous stresses, we believe it necessary to comment on its role in Poaceae abiotic stress response.

In monocots, like rice, Si is considered essential (Savant et al., 1997), despite the current classification of this element as quasi-essential (Epstein and Bloom, 2005), because its absence triggers dramatic consequences, namely yield loss, pathogen and abiotic stress increased susceptibility (Datnoff and Rodrigues, 2005). This importance may be partly due to the nature of monocots' cell walls, which are of type II (Yokoyama and Nishitani, 2004) and where Si may play a structural role connected to cell wall integrity, in a manner analogous to B in dicots' type I cell walls.

Si was shown to protect barley under Cr stress: it alleviated the ultrastructural disorders in both leaves and root tips and ameliorated net photosynthetic rate and stomatal conductance under heavy metal stress (Ali et al., 2013).

The deleterious effects of drought were mitigated by exogenous Si application in wheat: plants treated with Si displayed higher activities of SOD, CAT, and GR (glutathione reductase), had higher amounts of photosynthetic pigments and total thiols, while H2O2 content and protein oxidative stress decreased (Gong et al., 2005). Another study on wheat, in which gene expression analysis was performed, revealed that the drought tolerance in Si-treated wheat was accompanied by transcriptional reprogramming: genes involved in the ascorbate-reduced glutathione cycle, flavonoid biosynthesis and antioxidant response showed increased expression in Si-supplied plants (Ma D. et al., 2016).

Seed priming with Si can be very effective in protecting the growing plantlets from exogenous stresses: for example maize primed with Si displayed better resistance to alkaline stress through enhanced growth, photosynthesis, leaf relative water content and by increasing the activities of antioxidant enzymes, soluble sugars and proteins, while decreasing the contents of malondialdehyde, proline and Na+ (Abdel Latef and Tran, 2016).

Si can also establish positive interactions and synergy with other elements, such as, N: a recent study on rice showed indeed that Si basal application, coupled to post-flood N application, resulted in the highest tolerance to submergence, by reducing lodging, leaf chlorosis and senescence (Gautam et al., 2016).

Perspectives on the study of abiotic stress tolerance in Poaceae: the importance of landraces and their wild relatives

A serious consequence of the modern breeding strategies is the decrease of the agricultural biodiversity; this leads to a reduction in abiotic stress tolerance, because of the loss of specific genomic traits during domestication (Dwivedi et al., 2016). Therefore, the exploitation of the genetic resources represented by local landraces, or wild relatives, is a promising approach to find interesting genetic traits useful to improve breeding strategies of crops. This strategy has already been successfully tested in different Poaceae such as, wheat, rice, maize, and barley (Lopes et al., 2015; Dwivedi et al., 2016; Van Oosten et al., 2016). As example, different wheat and rice landraces have been recently used in high-throughput studies, describing thousands of SNPs possibly able to enhance drought and salt tolerance (Huang et al., 2010; Cavanagh et al., 2013). Moreover, at least 22 wild relatives of Oryza are known, and their genetic diversity can provide novel traits for drought tolerance (Van Oosten et al., 2016). Furthermore, wild relatives of rice (Oryza rufipogon Griff.), were recently used for a miRNA sequencing in drought stress condition (Zhang et al., 2017). The study led to the identification of 162 known miRNAs differentially expressed in drought stress condition and, notably, 69 new miRNAs candidates.

Recently, the genome sequencing of the Tibetan barley (Hordeum vulgare L. var. nudum), highlighted an interesting expansion of stress-related gene families (Zeng et al., 2015).

In recent years, new introgression lines between commercial cultivars and wild relatives have been generated in Poaceae. As an example, the wild rice Dongxiang accession (O. rufipogon Griff.) was used to generate drought tolerant accessions by the introgression of genetic traits in modern rice cultivars (Zhang et al., 2006).

Significant results in abiotic stress tolerance traits introgression were obtained also in Triticum. Wheat was improved in drought and salt stress tolerance by the wild relatives Aegilops umbellulata and Agropyron elongatum (Molnar et al., 2004; Colmer et al., 2006; Placido et al., 2013).

More recently, interesting abiotic stress-related loci were described in wild barley. Shen et al. (2016) showed a high salt tolerance in Tibetan wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum C. Koch) obtained by an enhanced TCA cycle, accumulation of sugar, and ROS detoxification. The interesting potential of Tibetan barley (Hordeum spontaneum C. Koch) was also described by Ahmed et al. (2013), who highlighted the drought and salt tolerance through an enhanced regulation in the glycine-betaine accumulation, in Na+/K+ ratio, sugar contents and antioxidant capacity against ROS at anthesis. Guo et al. (2016) described the potential of the calcium-sensor calcineurin B-like from H. spontaneum Qinghai-Tibet line (HsCBL8). Rice transgenic plants overexpressing HsCBL8 showed an improved salt stress tolerance by increased proline accumulation, plasma membrane protection and decrease in Na+ uptake.

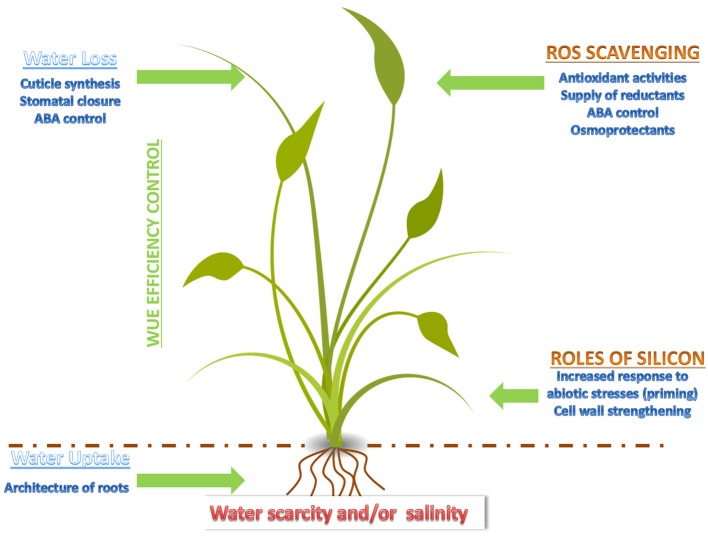

These results show that the study of landraces and wild relatives is useful to design strategies aiming at the improvement of the abiotic stress response in Poaceae. A schematic summary concerning the factors and key events affecting the response of monocots to drought and salt stress is presented in Figure 1. Approaches using—omics are, in this respect, particularly valuable, as they contribute to identify candidates and to shed light on the regulatory networks underlying the increased tolerance of Poaceae landraces to abiotic stresses.

Figure 1.

Cartoon depicting the major events and factors affecting drought and salt stress response in a monocot.

Author contributions

GG and SE conceived the idea of writing the paper. SL, JH, GG, and SE wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

JH and GG gratefully acknowledge the support by the FNR—Fonds National de la Recherche, Luxembourg, (project CANCAN C13/SR/5774202 and project CADWALL INTER/FWO/12/14).

References

- Abdel Latef A. A., Tran L.-S. P. (2016). Impacts of priming with silicon on the growth and tolerance of maize plants to alkaline stress. Front. Plant Sci. 7:243. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed I. M., Cao F., Zhang M., Chen X., Zhang G., Wu F. (2013). Difference in yield and physiological features in response to drought and salinity combined stress during anthesis in tibetan wild and cultivated barleys. PLoS ONE 8:e77869. 10.1371/journal.pone.0077869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alavilli H., Awasthi J. P., Rout G. R., Sahoo L., Lee B., Panda S. K. (2016). Overexpression of a barley aquaporin Gene, HvPIP2;5 confers salt and osmotic stress tolerance in yeast and plants. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1566. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S., Farooq M. A., Yasmeen T., Hussain S., Arif M. S., Abbas F., et al. (2013). The influence of silicon on barley growth, photosynthesis and ultra-structure under chromium stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety 89, 66–72. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2012.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An P., Li X., Zheng Y., Matsuura A., Abe J., Eneji A. E., et al. (2014). Effects of NaCl on root growth and cell wall composition of two soyabean cultivars with contrasting salt tolerance. J. Agric. Crop Sci. 200, 212–218. 10.1111/jac.12060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels D., Sunkar R. (2005). Drought and salt tolerance in plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 24, 23–58. 10.1080/07352680590910410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behr M., Legay S., Hausman J. F., Guerriero G. (2015). Analysis of cell wall-related genes in organs of Medicago sativa L. under different abiotic stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 16104–16124. 10.3390/ijms160716104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi H., Luang S., Li Y., Bazanova N., Morran S., Song Z., et al. (2016). Identification and characterization of wheat drought-responsive MYB transcription factors involved in the regulation of cuticle biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 5363–5380. 10.1093/jxb/erw298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao P. J., Bartley L. E., Jung K. H., Ronald P. C. (2008). Construction of a rice glycosyltransferase phylogenomic database and identification of rice-diverged glycosyltransferases. Mol. Plant 1, 858–877. 10.1093/mp/ssn052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao P. J., Jung K. H., Ronald P. C. (2010). A survey of databases for analysis of plant cell wall-related enzymes. Bioenergy Res. 3, 108–114. 10.1007/s12155-010-9082-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardi M., Castiglia D., Ferrara M., Guerriero G., Chiurazzi M., Esposito S. (2015). The effects of salt stress cause a diversion of basal metabolism in barley roots: possible different roles for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase isoforms. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 86, 44–54. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardi M., Chibani K., Cafasso D., Rouhier N., Jacquot J. P., Esposito S. (2011). Abscisic acid effects on activity and expression of different glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase isoforms in barley (Hordeum vulgare). J. Exp. Bot. 62, 4013–4023. 10.1093/jxb/err100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casaretto J. A., El-kereamy A., Zeng B., Stiegelmeyer S. M., Chen X., Bi Y. M., et al. (2016). Expression of OsMYB55 in maize activates stress-responsive genes and enhances heat and drought tolerance. BMC Genomics 17:312. 10.1186/s12864-016-2659-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh C. R., Chao S., Wang S., Huang B. E., Stephen S., Kiani S., et al. (2013). Genome-wide comparative diversity uncovers multiple targets of selection for improvement in hexaploid wheat landraces and cultivars. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 8057–8062. 10.1073/pnas.1217133110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb J. N., Declerck G., Greenberg A., Clark R., McCouch S. (2013). Next-generation phenotyping: requirements and strategies for enhancing our understanding of genotype-phenotype relationships and its relevance to crop improvement. Theor. Appl. Genet. 126, 867–887. 10.1007/s00122-013-2066-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colmer T. D., Flowers T. J., Munns R. (2006). Use of wild relatives to improve salt tolerance in wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 1059–1078. 10.1093/jxb/erj124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csiszár J., Galle A., Horvath E., Dancso P., Gombos M., Vary Z., et al. (2012). Different peroxidase activities and expression of abiotic stress-related peroxidases in apical root segments of wheat genotypes with different drought stress tolerance under osmotic stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 52, 119–129. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2011.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui P., Liu H., Islam F., Li L., Farooq M. A., Ruan S., et al. (2016). OsPEX11, a peroxisomal biogenesis factor 11, contributes to salt stress tolerance in Oryza sativa. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1357. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Wang M., Zhou H., Li M., Huang L., Yin X., et al. (2016). OsSGL, a novel DUF1645 domain-containing protein, confers enhanced drought tolerance in transgenic rice and Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 7:2001. 10.3389/fpls.2016.02001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Santo S., Stampfl H., Krasensky J., Kempa S., Gibon Y., Petutschnig E., et al. (2012). Stress-induced GSK3 regulates the redox stress response by phosphorylating glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24, 3380–3392. 10.1105/tpc.112.101279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datnoff L. E., Rodrigues F. A. (2005). The role of silicon in suppressing rice diseases. APSnet Features. 766–773. 10.1094/APSnetFeature-2005-0205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi S. L., Ceccarelli S., Blair M. W., Upadhyaya H. D., Are A. K., Ortiz R. (2016). Landrace germplasm for improving yield and abiotic stress adaptation. Trends Plant Sci. 21, 31–42. 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein E., Bloom A. J. (2005). Mineral Nutrition of Plants: Principles and Perspectives, 2nd Edn. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito S. (2016). Nitrogen assimilation, abiotic stress and Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase: the full circle of reductants. Plants 5:24. 10.3390/plants5020024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall H. L., Philippe F., Domon J.-M., Gillet F., Pelloux J., Rayon C. (2015). Cell wall metabolism in response to abiotic stress. Plants 4, 112–166. 10.3390/plants4010112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam P., Lal B., Tripathi R., Shahid M., Baig M. J., Raja R., et al. (2016). Role of silica and nitrogen interaction in submergence tolerance of rice. Environ. Exp. Bot. 125, 98–109. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2016.02.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gill B. S., Appels R., Botha-Oberholster A. M., Buell C. R., Bennetzen J. L., Chalhoub B., et al. (2004). A workshop report on wheat genome sequencing: International Genome Research on Wheat Consortium. Genetics 168, 1087–1096. 10.1534/genetics.104.034769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill S. S., Tuteja N. (2010). Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 48, 909–930. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong H., Zhu X., Chen K., Wang S., Zhang C. (2005). Silicon alleviates oxidative damage of wheat plants in pots under drought. Plant Sci. 169, 313–321. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2005.02.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L., Zhang Y., Zhang M., Li T., Dirk L. M., Downie B., et al. (2016). ZmGOLS2, a target of transcription factor ZmDREB2A, offers similar protection against abiotic stress as ZmDREB2A. Plant Mol. Biol. 90, 157–170. 10.1007/s11103-015-0403-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerriero G., Hausman J. F., Legay S. (2016a). Silicon and the plant extracellular matrix. Front. Plant Sci. 7:463. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerriero G., Hausman J. F., Strauss J., Ertan H., Siddiqui K. S. (2016b). Lignocellulosic biomass: biosynthesis, degradation and industrial utilization. Eng. Life Sci. 16, 1–16. 10.1002/elsc.201400196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guerriero G., Legay S., Hausman J. F. (2014a). Alfalfa cellulose synthase gene expression under abiotic stress: a Hitchhiker's guide to RT-qPCR normalization. PLoS ONE 9:e103808. 10.1371/journal.pone.0103808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerriero G., Sergeant K., Hausman J. F. (2014b). Wood biosynthesis and typologies: a molecular rhapsody. Tree Physiol. 34, 839–855. 10.1093/treephys/tpu031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W., Chen T., Hussain N., Zhang G., Jiang L. (2016). Characterization of salinity tolerance of transgenic rice lines harboring HsCBL8 of wild barley (Hordeum spontanum) line from Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1678. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gürel F., Öztürk Z. N., Uçarlı C., Rosellini D. (2016). Barley genes as tools to confer abiotic stress tolerance in crops. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1137. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann T. (2015). The plant cell wall integrity maintenance mechanism-concepts for organization and mode of action. Plant Cell Physiol. 56, 215–223. 10.1093/pcp/pcu164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi H., Murata N. (1998). Genetically engineered enhancement of salt tolerance in higher plants, in Molecular Mechanisms and Molecular Regulation, Stress Response of Photosynthetic Organisms, eds Sato K., Murata N. (Amsterdam: Elsevier; ), 133–148. 10.1016/b978-0-444-82884-2.50012-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He G. H., Xu Y. J., Wang X. Y., Liu M. J., Li S. P., Chen M., et al. (2016). Drought-responsive WRKY transcription factor genes TaWRKY1 and TaWRKY33 from wheat confer drought and/or heat resistance in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 16:116 10.1186/s12870-016-0806-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Li L., Xu H., Xi J., Cao X., Xu H., et al. (2016). A rice jacalin-related mannose-binding lectin gene, OsJRL, enhances Escherichia coli viability under high salinity stress and improves salinity tolerance of rice. Plant Biol. 19, 257–267. 10.1111/plb.12514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston K., Tucker M. R., Chowdhury J., Shirley N., Little A. (2016). The plant cell wall: a complex and dynamic structure as revealed by the responses of genes under stress conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 7:984. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Wei X., Sang T., Zhao Q., Feng Q., Zhao Y., et al. (2010). Genome-wide association studies of 14 agronomic traits in rice landraces. Nat. Genet. 42, 961–967. 10.1038/ng.695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Rice Genome Sequencing Project (2005). The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature 436, 793–800. 10.1038/nature03895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iovieno P., Punzo P., Guida G., Mistretta C., Van Oosten M. J., Nurcato R., et al. (2016). Transcriptomic changes drive physiological responses to progressive drought stress and rehydration in tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 7:371. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H. Y., Nguyen H. P., Lee C. (2015). Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of rice pectin methylesterases: implication of functional roles of pectin modification in rice physiology. J. Plant Physiol. 183, 23–29. 10.1016/j.jplph.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaouthar F., Ameny F. K., Yosra K., Walid S., Ali G., Faiçal B. (2016). Responses of transgenic Arabidopsis plants and recombinant yeast cells expressing a novel durum wheat manganese superoxide dismutase TdMnSOD to various abiotic stresses. J. Plant Physiol. 198, 56–68. 10.1016/j.jplph.2016.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothari K. S., Dansana P. K., Giri J., Tyagi A. K. (2016). Rice stress associated protein 1 (OsSAP1) interacts with Aminotransferase (OsAMTR1) and pathogenesis-related 1a protein (OsSCP) and regulates abiotic stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1057. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi S., Nurcato R., De Lillo A., Lentini M., Grillo S., Esposito S. (2016). Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase plays a central role in the response of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) plants to short and long-term drought. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 105, 79–89. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lata C., Muthamilarasan M., Prasad M. (2015). Drought stress responses and signal transduction in plants, in Elucidation of Abiotic Stress Signaling in Plants, ed Pandey G. K. (New York, NY: Springer; ), 195–225. [Google Scholar]

- Lata C., Prasad M. (2011). Role of DREBs in regulation of abiotic stress responses in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 4731–4748. 10.1093/jxb/err210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lata C., Yadav A., Prasad M. (2011). Role of plant transcription factors in abiotic stress tolerance, in Abiotic Stress/Book2, ed Shanker A. (Rijeka: INTECH Open Access Publishers; ). Available online at: https://www.intechopen.com/books/howtoreference/abiotic-stress-response-in-plants-physiological-biochemical-and-genetic-perspectives/role-of-plant-transcription-factors-in-abiotic-stress-tolerance [Google Scholar]

- Legay S., Guerriero G., André C., Guignard C., Cocco E., Charton S., et al. (2016). MdMyb93 is a regulator of suberin deposition in russeted apple fruit skins. New Phytol. 212, 977–991. 10.1111/nph.14170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucci M. R., Lenucci M. S., Piro G., Dalessandro G. (2008). Water stress and cell wall polysaccharides in the apical root zone of wheat cultivars varying in drought tolerance. J. Plant Physiol. 165, 1168–1180. 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Li Y., Yin Z., Jiang J., Zhang M., Guo X. (2016). OsASR5 enhances drought tolerance through a stomatal closure pathway associated with ABA and H2O2 signalling in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 183–196. 10.1111/pbi.12601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobell D. B., Schlenker W., Costa-Roberts J. (2011). Climate trends and global crop production since 1980. Science 333, 616–620. 10.1126/science.1204531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes S. M., El-Basyoni I., Baenziger P. S., Singh S., Royo C., Ozbek K., et al. (2015). Exploiting genetic diversity from landraces in wheat breeding for adaptation to climate change. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 3477–3486. 10.1093/jxb/erv122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W., Deng M., Guo F., Wang M., Zeng Z., Han N., et al. (2016). Suppression of OsVPE3 enhances salt tolerance by attenuating vacuole rupture during programmed cell death and affects stomata development in rice. Rice 9, 65. 10.1186/s12284-016-0138-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D., Sun D., Wang C., Qin H., Ding H., Li Y., et al. (2016). Silicon application alleviates drought stress in wheat through transcriptional regulation of multiple antioxidant defense pathways. J. Plant Growth Regul. 35, 1–10. 10.1007/s00344-015-9500-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma F., Ni L., Liu L., Li X., Zhang H., Zhang A., et al. (2016). ZmABA2, an interacting protein of ZmMPK5, is involved in abscisic acid biosynthesis and functions. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14, 771–782. 10.1111/pbi.12427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. F., Tamai K., Ichii M., Wu G. F. (2002). A rice mutant defective in Si uptake. Plant Physiol. 130, 2111–2117. 10.1104/pp.010348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar I., Gaspar L., Sarvari E., Dulai S., Hoffmann B., Molnar-Lang M., et al. (2004). Physiological and morphological responses to water stress in Aegilops biuncialis and Triticum aestivum genotypes with differing tolerance to drought. Funct. Plant Biol. 31, 1149–1159. 10.1071/FP03143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura J. C., Bonine C. A., de Oliveira Fernandes Viana J., Dornelas M. C., Mazzafera P. (2010). Abiotic and biotic stresses and changes in the lignin content and composition in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 52, 360–376. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00892.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y., Yamaguchi M., Endo H., Rejab N. A., Ohtani M. (2015). NAC-MYB-based transcriptional regulation of secondary cell wall biosynthesis in land plants. Front. Plant Sci. 6:288. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang S., Zhu W., Hamilton J., Lin H., Campbell M., Childs K., et al. (2007). The TIGR rice genome annotation resource: improvements and new features. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, D846–D851. 10.1093/nar/gkl976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrotta L., Guerriero G., Sergeant K., Cai G., Hausman J. F. (2015). Target or barrier? The cell wall of early- and later-diverging plants vs cadmium toxicity: differences in the response mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 6:133. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placido D. F., Campbell M. T., Folsom J. J., Cui X., Kruger G. R., Baezinger P. S., et al. (2013). Introgression of novel traits from a wild wheat relative improves drought adaptation in wheat. Plant Physiol. 161, 1806–1819. 10.1104/pp.113.214262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravet K., Touraine B., Boucherez J., Briat J. F., Gaymard F., Cellier F. (2009). Ferritins control interaction between iron homeostasis and oxidative stress in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 57, 400–412. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03698.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redillas M. C., Jeong J. S., Kim Y. S., Jung H., Bang S. W., Choi Y. D., et al. (2012). The overexpression of OsNAC9 alters the root architecture of rice plants enhancing drought resistance and grain yield under field conditions. Plant Biotechnol. J. 10, 792–805. 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2012.00697.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds M., Tuberosa R. (2008). Translational research impacting on crop productivity in drought-prone environments. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 171–179. 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero A., Punzo P., Landi S., Costa A., Van Ooosten M., Grillo S. (2017). Improving plant water use efficiency through molecular genetics. Horticulturae 3:31 10.3390/horticulturae3020031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savant N. K., Snyder G. H., Datnoff L. E. (1997). Silicon management and sustainable rice production. Adv. Agron. 58, 151–199. 10.1016/S0065-2113(08)60255-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R., Cao P., Jung K. H., Sharma M. K., Ronald P. C. (2013). Construction of a rice glycoside hydrolase phylogenomic database and identification of targets for biofuel research. Front. Plant Sci. 4:330. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Lv B., Luo L., He J., Mao C., Xi D., et al. (2017). The NAC-type transcription factor OsNAC2 regulates ABA-dependent genes and abiotic stress tolerance in rice. Sci. Rep. 7:40641. 10.1038/srep40641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Q., Fu L., Dai F., Jiang L., Zhang G., Wu D. (2016). Multi-omics analysis reveals molecular mechanisms of shoot adaption to salt stress in Tibetan wild barley. BMC Genomics 17:889. 10.1186/s12864-016-3242-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Xu W., Jia Y., Wang M., Xia G. (2015). The wheat TaGBF1 gene is involved in the blue-light response and salt tolerance. Plant J. 84, 1219–1230. 10.1111/tpj.13082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenhaken R. (2015). Cell wall remodeling under abiotic stress. Front. Plant Sci. 5:771. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tester M., Langridge P. (2010). Breeding technologies to increase crop production in a changing world. Science 12, 818–822. 10.1126/science.1183700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Oosten M. J., Costa A., Punzo P., Landi S., Ruggiero A., Batelli G., et al. (2016). Genetics of drought stress tolerance in crop plants, in Drought Stress Tolerance in Plants, Vol. 2, eds Hossain M. A., Wani S. H., Bhattacharjee S., Burritt D. J., Phan Tran L.-S. (Berlin: Springer; ), 39–70. 10.1007/978-3-319-32423-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Virlouvet L., Jacquemot M.-P., Gerentes D., Corti H., Bouton S., Gilard F., et al. (2011). The ZmASR1 protein influences branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis and maintains kernel yield in maize under water-limited conditions. Plant Physiol. 157, 917–936. 10.1104/pp.111.176818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y., Lu Y. H., Song M., Wang Y., Xu W., Wu L., et al. (2015). Overexpression of a Triticum aestivum Calreticulin gene (TaCRT1) improves salinity tolerance in tobacco. PLoS ONE 10:e0140591. 10.1371/journal.pone.0140591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y., Sun X., Gao S., Qin F., Dai M. (2016). Deletion of an endoplasmic reticulum stress response element in a ZmPP2C-A gene facilitates drought tolerance of maize seedlings. Mol. Plant. 10, 456–469. 10.1016/j.molp.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. (2006). Transcriptional regulatory networks in cellular responses and tolerance to dehydration and cold stresses. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57, 781–803. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama R., Nishitani K. (2004). Genomic basis for cell-wall diversity in plants. A comparative approach to gene families in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 45, 1111–1121. 10.1093/pcp/pch151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang X., Geng X., Wang F., Liu Z., Zhang K., Zhao Y., et al. (2017). Overexpression of wheat ferritin gene TaFER-5B enhances tolerance to heat stress and other abiotic stresses associated with the ROS scavenging. BMC Plant Biol. 17:14. 10.1186/s12870-016-0958-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Long H., Wang Z., Zhao S., Tang Y., Huang Z., et al. (2015). The draft genome of Tibetan hulless barley reveals adaptive patterns to the high stressful Tibetan Plateau. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 1095–1100. 10.1073/pnas.1423628112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.-W., Long Y., Xue M.-D., Xiao X.-G., Pei X.-W. (2017). Identification of microRNAs in response to drought in common wild rice (Oryza rufipogon Griff.) shoots and roots. PLoS ONE 12:e0170330. 10.1371/journal.pone.0170330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Zhou S., Fu Y., Su Z., Wang X., Sun C. (2006). Identification of a drought tolerant introgression line derived from dongxiang common wild rice (O. rufipogon Griff.). Plant Mol. Biol. 62, 247–259. 10.1007/s11103-006-9018-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]