Abstract

Introduction

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) have an increased risk of comorbid conditions, including cardiovascular disease (CVD). Anemia is prevalent in the CKD population and worsens as kidney function declines, resulting in a diminished quality of life and increased morbidity/mortality. The purpose of this secondary analysis was to determine the real-world prevalence of CVD among patients with non-dialysis-dependent CKD (NDD-CKD), with and without comorbid anemia, and to assess the impact of these conditions on quality of life (QoL) and work productivity.

Methods

Data were drawn from the Adelphi CKD Disease-Specific Programme, conducted in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK (2012). Anonymized data were collected via patient record forms and patient-completed questionnaires. Patient data were stratified by anemic status and the presence of CVD comorbidity.

Results

Data were collected by physicians for 1993 patients, of whom 867 completed a patient-completed questionnaire. A total of 61.4% of patients had anemia, and the prevalence of anemia increased with CKD stage. Patients with anemia had a higher mean number of cardiovascular comorbidities than non-anemic patients (1.27 vs 0.95, respectively; P < 0.001). The presence of cardiovascular conditions was associated with a significantly reduced QoL (EuroQol EQ-5D-3L visual analog scale: coefficient, −5.68 in anemic patients; P = 0.028) and work productivity and activity impairment (WPAI activity impairment: coefficient, +8.04 in anemic patients; P = 0.032), particularly among anemic patients.

Conclusions

The presence of anemia in this cohort of NDD-CKD patients was high. The presence of concomitant cardiovascular conditions was more common in NDD-CKD patients with comorbid anemia, and was associated with reduced QoL and work productivity outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-017-0566-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Anemia, Chronic kidney disease, Cardiovascular disease, Erythropoietin, Quality of life

Introduction

Abnormal renal structure or function persisting for more than 3 months, defined as chronic kidney disease (CKD), has an estimated prevalence of 3.9–12.5% globally [1, 2]. Diagnosis and disease staging are based on kidney function, measured by glomerular filtration rate, and patients with stage 5 disease (glomerular filtration rate <15 mL/min/1.73 m2) frequently require dialysis [3]. Patients with CKD are at an increased risk of numerous comorbidities, and kidney function is predictive of such complications [4]. In particular, patients with CKD are at an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) compared with the general population. Although traditional risk factors for CVD, such as abnormal cholesterol profile, smoking, or physical inactivity, are frequently prevalent among patients with CKD, several large prospective studies have demonstrated that CKD itself remains an independent risk factor for CVD [4].

Anemia is a common complication of CKD that becomes more prevalent with declining kidney function, and is associated with reduced quality of life (QoL) and higher morbidity and mortality [5–7]. Endogenous erythropoietin (EPO) is the hormone responsible for stimulating erythropoiesis, and is primarily produced in response to hypoxia by renal interstitial fibroblasts and is mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor [8, 9]. Although the pathophysiology of anemia in CKD is not fully understood, it has been postulated that transition of these erythropoietin-producing cells to myofibroblasts reduces the number of cells that can produce EPO in response to hypoxia [10]. The development of recombinant human EPO (rHuEPO) has brought clinical and QoL improvements for patients with anemia. Recent evidence has shown that treatment with rHuEPO in predialysis patients with CKD may reduce mortality risk following initiation of dialysis [11]. However, evidence has demonstrated that treatment with rHuEPO to achieve higher Hb levels is associated with increased of cardiovascular (CV) events [12–15]. As a result, current recommendations advocate individualized treatment to balance the potential benefits and risks for each patient [16].

To achieve optimal outcomes with these treatments, the impact of CVD and anemia among patients with CKD needs to be elucidated. The purpose of this secondary analysis was to determine the real-world prevalence of CVD among patients with non-dialysis-dependent CKD (NDD-CKD), with and without comorbid anemia, and to assess the impact of these conditions on QoL and work productivity.

Methods

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was based on a market research survey adhering to the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC)/European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research (ESOMAR) international code on market and social research and therefore ethical approval was not sought.

Study Design

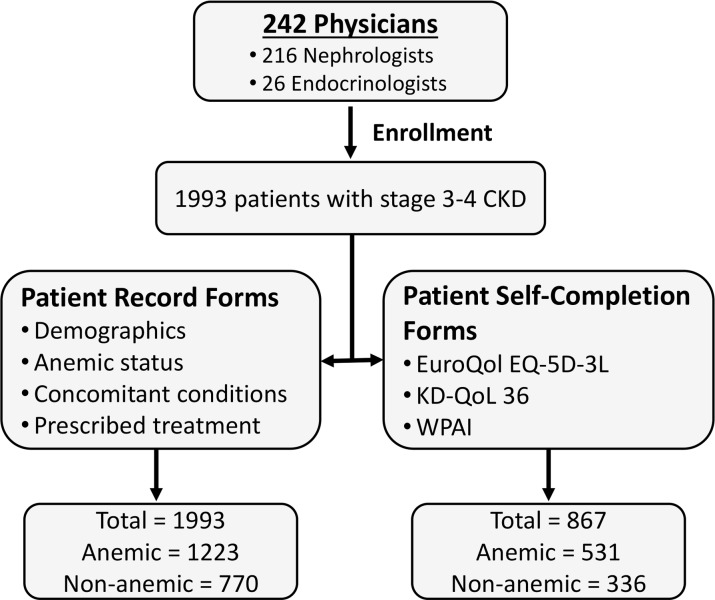

This was a multinational, cross-sectional survey of clinical practice conducted by Adelphi Real World (Bollington, UK). The Adelphi CKD Disease-Specific Programme (DSP) collected detailed information on patients, including the presence of concomitant conditions, particularly those relating to CVD, among anemic and non-anemic patients with moderate to end-stage CKD in Europe. Data for this secondary analysis were collected between June 2012 and September 2012 in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK and included patients with stage 3 [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥30 and <60] or 4 (eGFR ≥15 and <30) NDD-CKD. Figure 1 shows the study design, and a detailed description of the DSP methodology is provided elsewhere [17]. Informed consent was provided before collection of patient-reported data. Data were collected anonymously, with respondents identified by study numbers that were matched to linked responses from physicians and their respective patients.

Fig. 1.

Study design

Participants

Physicians (i.e., nephrologists and endocrinologists) who were qualified between 1971 and 2009, and who were actively involved in the drug management of patients with CKD, were eligible for participation. Nephrologists were required to enroll eight NDD-CKD patients, and endocrinologists were required to enroll 14 NDD-CKD patients (diagnosed previously or on the day of enrollment). Patients were classified as anemic if they had a physician-confirmed diagnosis of anemia, were prescribed treatment for anemia, or had a hemoglobin (Hb) level <12 g/dL (women) or <13 g/dL [men; per 2012 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guideline].

Outcome Measures

Physicians completed patient record forms comprising questions related to patient demographics, underlying cause of NDD-CKD, presence of anemia and other concomitant conditions, prescribed treatment, factors influencing treatment selection, and current symptoms (see Supplementary Table 1 for a full list of the terms used). As hypertension is a primary underlying cause of CKD, the association between this outcome and the presence of anemia was assessed. Patient self-completion forms were completed by the enrolled patients, and included the EuroQol EQ-5D-3L, the Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KD-QoL 36) instrument, and the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed statistically using Stata v13.1 (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). Additional analyses were also performed using the QPSMR Reflect Database. Analyses were performed on the total patient population as well as on the following subgroups: presence of CV comorbidity, no presence of CV comorbidity, presence of anemia, and no presence of anemia.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to calculate odds ratios for the presence of comorbid conditions and the underlying cause of CKD being hypertension among patients with anemia. Multivariable negative binomial regression analysis was used to calculate an incidence rate ratio for the number of comorbid conditions among patients with anemia. Regressions were adjusted for age, gender, diabetes as an underlying cause of CKD, and body mass index (BMI). Multivariable linear regression analysis was used to determine the impact of CV comorbidities on QoL and activity impairment measures in patients with anemia versus patients without anemia. Regressions were adjusted for age, gender, diabetes as an underlying cause of CKD, and BMI. For bivariate associations between patient characteristics and CV comorbidities, analysis was performed using Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test (for categorical variables), and Mann–Whitney test or Kruskal–Wallis test (for continuous variables).

Results

Patient Characteristics

In total, 242 physicians (216 nephrologists and 26 endocrinologists) participated in the study and provided data for 1993 patients with stage 3–4 NDD-CKD. Patient demographics and characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Most patients (1223; 61.4%) were classified as anemic [physician-confirmed diagnosis of anemia, n = 636 (31.9%); prescribed treatment for anemia, 698 (35%); Hb level <12 g/dL (women) or <13 g/dL (men), 1097 (55%)] and, compared with non-anemic patients, were older and more likely to be male. Approximately 35% of patients were receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors; the use of ACE inhibitors was not different between anemic and non-anemic patients. There were also differences between these two groups with regard to employment status, with significantly more anemic patients being unemployed or retired. Self-completion forms were completed by 867 matched patients, who provided QoL and work productivity and activity impairment data.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics by anemia status

| Characteristics | Non-anemic (n = 770) | Anemic (n = 1223) | Total population (N = 1993) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 421 (54.7) | 767 (62.7) | 1188 (59.6) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 62.5 (14.8) | 66.5 (14.5) | 64.9 (14.7) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.1 (5.0) | 26.7 (4.9) | 26.9 (5.0) | 0.209 |

| Years since CKD diagnosis | 0.93 (1.3) | 0.94 (0.98) | 0.94 (1.1) | 0.17 |

| Years since anemia diagnosis | – | 1.7 (3.6) | – | – |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 138.1 (16.6) | 138.5 (17.5) | 138.4 (17.2) | 0.554 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 78.0 (11.6) | 77.6 (11.8) | 77.7 (11.8) | 0.735 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.633 | |||

| Smoker | 82 (11.8) | 129 (11.7) | 211 (11.8) | |

| Ex-smoker | 240 (34.4) | 402 (36.6) | 642 (35.7) | |

| Never smoked | 375 (53.8) | 568 (51.7) | 943 (52.5) | |

|

Years smoked (current smokers) |

24.6 (12.5) | 28.4 (14.5) | 26.9 (13.8) | 0.065 |

|

Daily cigarettes (current smokers) |

13.5 (6.3) | 14.6 (7.9) | 14.2 (7.3) | 0.438 |

| Employment status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Employed | 257 (34.2) | 207 (17.5) | 464 (24.0) | |

| Unemployed | 40 (5.3) | 87 (7.3) | 127 (6.6) | |

| Retired | 366 (48.7) | 744 (62.8) | 1110 (57.4) | |

| Other | 88 (11.7) | 146 (12.3) | 234 (12.1) | |

| Living circumstances, n (%) | 0.012 | |||

| Alone | 146 (19.7) | 228 (19.5) | 374 (19.5) | |

| With friends, spouse, partner, or other family | 572 (77.1) | 878 (74.9) | 1450 (75.8) | |

| Nursing home, sheltered housing, or homeless | 14 (1.9) | 55 (4.7) | 69 (3.6) | |

| Other | 10 (1.4) | 11 (0.9) | 21 (1.1) | |

| Number of concomitant CV conditions* | 0.95 (1.1) | 1.27 (1.3) | 1.15 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| Underlying cause of CKD: hypertension | 392 (51.4) | 719 (59.4) | 1111 (56.3) | <0.001 |

| Underlying cause of CKD: diabetes | 336 (44.0) | 512 (42.3) | 848 (43.0) | 0.455 |

| Concomitant conditions, n (%) | ||||

| Dyslipidemia | 316 (41.6) | 536 (44.3) | 852 (43.3) | 0.243 |

| Coronary heart disease | 109 (14.4) | 270 (22.3) | 379 (19.3) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 57 (7.5) | 207 (17.1) | 264 (13.4) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 52 (6.9) | 136 (11.2) | 188 (9.6) | 0.001 |

| Arrhythmia | 53 (7.0) | 116 (9.6) | 169 (8.6) | 0.047 |

| Heart attack/MI/UA | 35 (4.6) | 83 (6.9) | 118 (6.0) | 0.041 |

| Other CV | 43 (5.7) | 73 (6.0) | 116 (5.9) | 0.769 |

| CVA/TIA | 32 (4.2) | 76 (6.3) | 108 (5.5) | 0.053 |

| Stroke | 22 (2.9) | 44 (3.6) | 66 (3.4) | 0.441 |

| Concomitant treatment, n (%) | 0.598 | |||

| ACE inhibitor | 271 (35.2) | 445 (36.4) | 716 (35.9) | |

Data are presented as mean (SD) unless otherwise noted. P values compare anemic and non-anemic patients and are calculated from Fisher’s exact test, Chi-squared test (categorical variables), a Mann–Whitney test or Kruskal–Wallis test (continuous variables), or a Mann–Whitney test (*only)

ACE angiotensin-converting enzyme, BMI body mass index, CKD chronic kidney disease, CV cardiovascular, CVA cerebrovascular accident, CVD cardiovascular disease, MI myocardial infarction, SD standard deviation, TIA transient ischemic attack, UA unstable angina

Relationship Between Cardiovascular Disease and Anemia

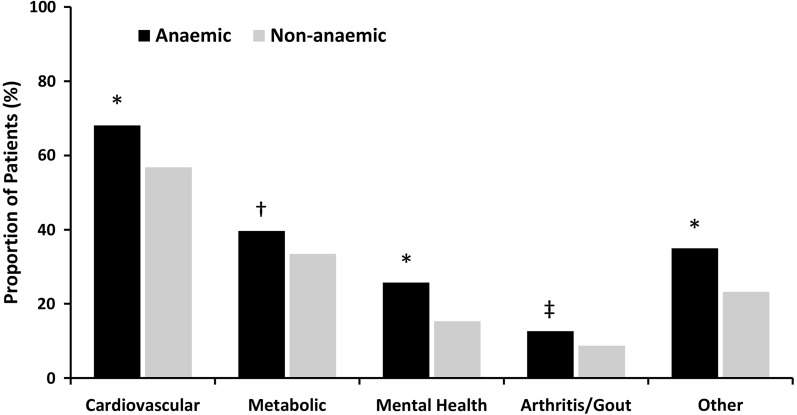

On the basis of patient record forms, the most frequent concomitant conditions experienced by both anemic and non-anemic patients were CV-related, followed by metabolic diseases and mental health disorders (Fig. 2). Patients with anemia had more CV-related concomitant conditions than non-anemic patients (non-anemic, 0.95; anemic, 1.27; P < 0.001). Hypertension was the underlying cause of CKD in 51.4% of the total population, and was more prevalent as the underlying cause among anemic patients (59.4%) compared with nonanemic patients (56.3%) (Table 1). Of the CV-related comorbidities, dyslipidemia was the most common condition, and was prevalent in 44.3% and 41.6% of anemic and non-anemic patients, respectively. Compared with non-anemic patients, those with anemia had a significantly higher prevalence of arrhythmia, heart attack/myocardial infarction/unstable angina, coronary heart disease, heart failure, and peripheral arterial disease (Table 1). The complete results of logistic regression for concomitant conditions, using the non-anemic cohort as a reference category, are shown in Table 2. Anemic status remained independently associated with the likelihood of coronary heart disease (odds ratio, 1.41; 95% CI 1.03–1.94; P = 0.032) and peripheral arterial disease (odds ratio, 1.80; 95% CI 1.25–2.60; P = 0.002). Negative binomial modelling demonstrated that anemia was associated with a greater number of concomitant CV conditions (incidence rate ratio, 1.17; 95% CI 1.03–1.31; P = 0.012).

Fig. 2.

Concomitant conditions experienced by anemic and non-anemic NDD-CKD patients. *P < 0.001; † P = 0.005; ‡ P = 0.008

Table 2.

Association between anemia and concomitant CVD conditions

| Outcome | Presence of anemia | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying cause of CKD: hypertension |

1.19 (0.92, 1.53) |

0.190 |

| Stroke |

0.98 (0.55, 1.76) |

0.951 |

| CVA/TIA |

1.06 (0.63, 1.78) |

0.818 |

| Dyslipidemia |

1.04 (0.81, 1.33) |

0.760 |

| Arrhythmia |

1.09 (0.72, 1.65) |

0.676 |

| Heart attack/MI/unstable angina |

1.27 (0.83, 1.95) |

0.270 |

| Coronary heart disease |

1.41 (1.03, 1.94) |

0.032 |

| Heart failure |

1.43 (0.96, 2.14) |

0.080 |

| Peripheral arterial disease |

1.80 (1.25, 2.60) |

0.002 |

| Other CV |

1.12 (0.53, 2.33) |

0.768 |

| Number of concomitant CV conditions* |

1.17 (1.03, 1.31) |

0.012 |

Values are odds ratios (95% confidence interval) of anemia increasing the likelihood of each outcome (logistic models) or (*) incidence rate ratios (negative binomial models). Dependent variables are the concomitant conditions listed or (*) number of concomitant conditions; independent variable is anemia status. Reference category is the non-anemic group. Regressions are adjusted for age, gender, stage/dialysis status, diabetes as an underlying cause of CKD, and BMI

BMI body mass index, CKD chronic kidney disease, CVA cerebrovascular accident, TIA transient ischemic attack

Cardiovascular Disease, Anemia, and Quality of Life

In anemic patients, multiple linear regression analysis revealed that the presence of CV conditions was significantly associated with lower QoL, as measured by EQ-5D visual analog scale (VAS) (coefficient, −5.68; 95% CI −10.76 to −0.61; P = 0.028), KD-QoL 36: effects of kidney disease (coefficient, −6.09; 95% CI −11.23 to −0.95; P = 0.021), and KD-QoL 36: SF-12 physical health composite (coefficient, −2.38; 95% CI −4.72 to −0.05; P = 0.046) (Table 3). No associations between the presence of CV conditions and QoL were observed in non-anemic patients or in the total population. Scores for all QoL measures, stratified by anemic status and presence of CV conditions, are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 3.

Association between CV conditions and quality of life by anemic status

| Characteristics | Non-anemic (n = 336) |

Anemic (n = 531) |

Total population (N = 867) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D health index |

0.00 (−0.06 to 0.06) P = 0.946 |

−0.06 (−0.12 to 0.00) P = 0.068 |

−0.04 (−0.09 to 0.01) P = 0.093 |

| EQ-5D VAS |

1.10 (−4.00 to 6.19) P = 0.670 |

−5.68 (−10.76 to −0.61) P = 0.028 |

−3.43 (−7.39 to −0.54) P = 0.090 |

| KD-QoL 36: symptoms/problems |

0.69 (−3.72 to 5.09) P = 0.758 |

−3.21 (−8.12 to 1.70) P = 0.198 |

−2.21 (−5.81 to 1.39) P = 0.228 |

| KD-QoL 36: effects of kidney disease |

1.22 (−4.13 to 6.57) P = 0.652 |

−6.09 (−11.23 to −0.95) P = 0.021 |

−3.80 (−7.86 to 0.26) P = 0.066 |

| KD-QoL 36: burden of kidney disease |

4.50 (−2.43 to 11.44) P = 0.201 |

−4.48 (−10.89 to 1.93) P = 0.169 |

−1.63 (−7.05 to 3.79) P = 0.554 |

| KD-QoL 36: SF-12 physical health composite |

−0.47 (−3.25 to 2.31) P = 0.737 |

−2.38 (−4.72 to −0.05) P = 0.046 |

−1.83 (−3.83 to 0.17) P = 0.073 |

| KD-QoL 36: SF-12 mental health composite |

1.87 (−0.54 to 4.28) P = 0.127 |

−1.49 (−3.83 to 0.84) P = 0.208 |

−0.26 (−1.96 to 1.44) P = 0.761 |

Values are coefficients (95% confidence interval) from ordinary least squares multiple linear regression models. Reference category is those without CV conditions. Regressions are adjusted for age, gender, stage/dialysis status, diabetes as an underlying cause of CKD, and BMI

BMI body mass index, CKD chronic kidney disease, CV cardiovascular, KD-QoL 36 kidney disease quality of life, VAS visual analog scale

Cardiovascular Disease, Anemia, and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment

In anemic patients only, multiple linear regression analysis revealed that the presence of CV conditions was significantly associated with WPAI: activity impairment (coefficient, 8.04; 95% CI 0.70–15.39; P = 0.032) (Table 4). No significant associations between the presence of CV conditions and work activity impairment were observed in non-anemic patients or in the total population. Scores for all WPAI measures, stratified by anemic status and presence of CV conditions, are presented in Supplementary Table 3.

Table 4.

Association between CV conditions and work productivity and activity impairment

| Characteristics | Non-anemic (n = 336) |

Anemic (n = 531) |

Total population (N = 867) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WPAI: percentage of work time missed |

−1.42 (−4.74 to 1.90) P = 0.393 |

6.81 (−0.39 to 14.02) P = 0.063 |

2.41 (−1.21 to 6.03) P = 0.189 |

| WPAI: percentage of work time impaired |

−4.22 (−12.50 to 4.07) P = 0.312 |

6.81 (−2.31 to 15.92) P = 0.140 |

2.19 (−4.78 to 9.15) P = 0.533 |

| WPAI: overall work impairment |

−5.99 (−15.43 to 3.46) P = 0.209 |

8.53 (−3.28 to 20.33) P = 0.153 |

2.04 (−5.65 to 9.72) P = 0.599 |

| WPAI: activity impairment |

−2.57 (−9.50 to 4.35) P = 0.463 |

8.04 (0.70 to 15.39) P = 0.032 |

4.31 (−1.35 to 9.97) P = 0.135 |

Values are coefficients (95% confidence interval) from ordinary least-squares multiple linear regression models. Reference category is those without CV conditions. Regressions are adjusted for age, gender, stage/dialysis status, diabetes as an underlying cause of CKD, and BMI

BMI body mass index, CKD chronic kidney disease, CV cardiovascular, WPAI work productivity and activity impairment

Discussion

This analysis of multinational, cross-sectional data representing real-world clinical practice confirms a high prevalence of physician-assessed anemia in patients with stage 3–4 NDD-CKD. In this population, anemia was associated with a higher number of concomitant conditions, in particular CVD. The presence of concomitant CVD and anemia was associated with reduced QoL measures and work productivity and greater activity impairment.

Previous studies have shown that there is a direct relationship between older age and an increased prevalence in anemia, irrespective of renal function [18, 19]. Similar to these studies, we found that patients with anemia were significantly older than those without anemia. A US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) study found that, in patients with CKD, CVD correlated with CKD severity as well as with age [20]. A UK prospective, observational study in patients with CKD, followed up from the time of diagnosis of diabetes, found that CVD was the most common cause of mortality, and that CVD risk increased with progression of nephropathy from 0.7% in non-nephrotic patients to 12.1% in patients with the most advanced stage of nephropathy (i.e., elevated plasma creatinine or renal replacement therapy). Additionally, the proportion of CV-related deaths increased from 51% in non-nephrotic patients to 75% in patients with advanced nephropathy [21]. It has been suggested that the pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying CKD and CVD may mutually amplify each other, therefore causing a greater impact on patient health [22]. Furthermore, as demonstrated by de Silva et al. [23], a high proportion of patients with CVD have both CKD and anemia, and these two conditions are closely related. In this population, anemia and CKD are associated with increased all-cause mortality, and this risk has been shown to be additive [22, 23].

A recent study demonstrated that anemia in CKD is associated with increased disease burden and activity impairment as well as with diminished QoL [24]. Significantly lower QoL has previously been demonstrated in patients with CKD compared with matched controls, even in early stages of disease, with scores deteriorating at more advanced CKD stages [25]. The current study goes further and shows that, in a CKD population, the presence of both anemia and CVD is associated with a lower QoL, as measured by several QoL measures.

This study has limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Selection bias may have occurred as a result of recruiting a selected group of physicians to enroll patients. In addition, because inclusion depended on the patient attending a clinic, patients who attend more frequently were more likely to be enrolled. Although consecutive sampling provides representation of a real-world consulting CKD population, this design may limit the generalizability of the results. Furthermore, less than half of the enrolled patients completed the patient self-completion form that captured QoL data. As participants could have pre-existing CKD, no standardized diagnostic procedure for CKD was used, and adjustments for kidney function were not made. In addition, although the cutoff criteria for anemia were defined in accordance with KDIGO guidelines, patients receiving anemia treatment, or who had a physician-confirmed diagnosis of anemia, were classified as being anemic without further testing. Another limitation of this study is that there are no data on iron parameters (i.e., ferritin, transferrin saturation). It is well known that iron is a crucial element that reduces platelet count and also improves mitochondrial and cardiac function [26, 27]. Understanding more about iron stores can reveal meaningful pathways in the relationship between anemia and CVD in patients with CKD. Lastly, as this was an observational study of data obtained from existing medical records, the non-interventional and cross-sectional design do not allow for any cause and effect inferences to be made.

Conclusions

In this cross-sectional survey of clinical practice, a high prevalence of anemia was found in patients with CKD. CVD comorbidities were more common among anemic patients compared with non-anemic patients, and were associated with significant decreases in QoL indicators.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Sponsorship, article processing charges, and medical writing support were funded by Astellas Pharma, Inc. The authors thank Anusha Bolana, Frances O’Connor, Kay Chapman, and Cleo Hall, of Darwin Healthcare Communications, who provided medical writing and editorial services on behalf of Astellas Pharma, Inc. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

This paper is our original work and the results presented have not been published previously in whole or in part, except for in abstract form. All authors contributed equally to the study. AC and DS helped design the analysis, and developed and reviewed the manuscript. JJ, JP, and AH designed and fielded the CKD DSP, analyzed the data used for publication, and reviewed the manuscript.

Disclosures

Adrian Covic, James Jackson, Anna Hadfield, James Pike, and Dimitrie Siriopol have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was based on a market research survey adhering to the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC)/European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research (ESOMAR) international code on market and social research and therefore ethical approval was not sought.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are the intellectual property of Adelphi Real World and are not publicly available. However, data can be provided upon request (james.jackson@adelphigroup.com).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced Content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/C848F06074935876.

References

- 1.NICE. Chronic kidney disease in adults: assessment and management. 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg182/resources/chronic-kidney-disease-in-adults-assessment-and-management-pdf-35109809343205. Accessed Mar 2015. [PubMed]

- 2.Trifiro G, Sultana J, Giorgianni F, et al. Chronic kidney disease requiring healthcare services: a new approach to evaluate epidemiology of renal disease. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:268362. doi: 10.1155/2014/268362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.KDIGO Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;3(1):1–150. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2012.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coresh J, Astor B, Sarnak MJ. Evidence for increased cardiovascular disease risk in patients with chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2004;13(1):73–81. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200401000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Astor BC, Muntner P, Levin A, Eustace JA, Coresh J. Association of kidney function with anemia: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988–1994) Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(12):1401–1408. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.12.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Locatelli F, Pisoni RL, Combe C, et al. Anaemia in haemodialysis patients of five European countries: association with morbidity and mortality in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(1):121–132. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McFarlane SI, Chen SC, Whaley-Connell AT, et al. Prevalence and associations of anemia of CKD: Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51(4 Suppl 2):S46–S55. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haase VH. Regulation of erythropoiesis by hypoxia-inducible factors. Blood Rev. 2013;27(1):41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu H, Liu X, Jaenisch R, Lodish HF. Generation of committed erythroid BFU-E and CFU-E progenitors does not require erythropoietin or the erythropoietin receptor. Cell. 1995;83(1):59–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haase VH. Mechanisms of hypoxia responses in renal tissue. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(4):537–541. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012080855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe Y, Akizawa T, Saito A, et al. Effect of predialysis recombinant human erythropoietin on early survival after hemodialysis initiation in patients with chronic kidney disease: Co-JET Study. Ther Apher Dial. 2016;20(6):598–607. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.12425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Besarab A, Bolton WK, Browne JK, et al. The effects of normal as compared with low hematocrit values in patients with cardiac disease who are receiving hemodialysis and epoetin. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(9):584–590. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808273390903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drueke TB, Locatelli F, Clyne N, et al. Normalization of hemoglobin level in patients with chronic kidney disease and anemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(20):2071–2084. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfeffer MA, Burdmann EA, Chen CY, et al. A trial of darbepoetin alfa in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(21):2019–2032. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL, et al. Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(20):2085–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Kidney Foundation KDIGO clinical practice guideline for anemia in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2(4):288–335. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2012.33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, Karavali M, Piercy J. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: Disease-Specific Programmes—a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(11):3063–3072. doi: 10.1185/03007990802457040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowling CB, Inker LA, Gutierrez OM, et al. Age-specific associations of reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate with concurrent chronic kidney disease complications. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(12):2822–2828. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06770711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guralnik JM, Eisenstaedt RS, Ferrucci L, Klein HG, Woodman RC. Prevalence of anemia in persons 65 years and older in the United States: evidence for a high rate of unexplained anemia. Blood. 2004;104(8):2263–2268. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.United States Renal Data System. Chronic kidney disease in the adult NHANES population: USRDS Annual Report Data 2009 (updated 2009). http://www.usrds.org/2009/pdf/V1_01_09.PDF. Accessed 2 Feb 2015.

- 21.Adler AI, Stevens RJ, Manley SE, Bilous RW, Cull CA, Holman RR. Development and progression of nephropathy in type 2 diabetes: the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS 64) Kidney Int. 2003;63(1):225–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Putten K, Braam B, Jie KE, Gaillard CA. Mechanisms of disease: erythropoietin resistance in patients with both heart and kidney failure. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2008;4(1):47–57. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Silva R, Rigby AS, Witte KK, et al. Anemia, renal dysfunction, and their interaction in patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(3):391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eriksson D, Goldsmith D, Teitsson S, Jackson J, van Nooten F. Cross-sectional survey in CKD patients across Europe describing the association between quality of life and anaemia. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s12882-016-0312-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pagels AA, Soderkvist BK, Medin C, Hylander B, Heiwe S. Health-related quality of life in different stages of chronic kidney disease and at initiation of dialysis treatment. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:71. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hazara AM, Bhandari S. Intravenous iron administration is associated with reduced platelet counts in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2015;40(1):20–23. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor D, Bhandari S, Seymour AM. Mitochondrial dysfunction in uremic cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015;308(6):F579–F587. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00442.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are the intellectual property of Adelphi Real World and are not publicly available. However, data can be provided upon request (james.jackson@adelphigroup.com).