Abstract

Introduction

There are no real-world data on antiviral prophylaxis (AP) duration and risk of herpes zoster (HZ) given AP duration in patients receiving autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplants (auto-HSCT). The objectives of this study are to describe the duration of AP and to compare incidence of HZ by AP duration in auto-HSCT patients.

Methods

This is a retrospective, observational database (Marketscan®) study. This study included patients ≥18 years old who had auto-HSCT during 2009–2013, had chemotherapy within 60 days prior to auto-HSCT (latest chemotherapy date within the 60 days was the study enrollment date), and had continuous health plan enrollment for at least 365 days before and after the study enrollment date. AP duration was the sum of days supply of all AP prescriptions from 30 days before to 365 days after the study enrollment date. Patients were followed from the study enrollment date to the end of continuous health plan enrollment, death, or December 31, 2014 to assess HZ incidence. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to examine the association between the risk of HZ and AP duration.

Results

This study identified 1959 eligible auto-HSCT patients, of whom 93.0% were prescribed AP. Average AP duration was 220 days (SD = 122), while 200 (11%) patients had AP for ≥1 year. HZ incidence was 42.4/1000 person-years (PY) (95% CI 36.5, 49.0) for the overall auto-HSCT cohort. Among patients who received AP, duration of AP prescriptions and HZ incidence were inversely related. Compared with patients who were on AP for 1–89 days, patients with AP duration of 180–269 days [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.576, p = 0.019], 270–359 days (HR = 0.594, p = 0.023), and ≥360 days (HR = 0.309, p < 0.001) had significantly lower risk of HZ.

Conclusion

Auto-HSCT patients are at increased risk for HZ, even when prescribed AP. A safe and effective vaccine against HZ for auto-HSCT patients could be a useful adjunctive prevention strategy.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-017-0553-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Antiviral prophylaxis, Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplants, Auto-HSCT, Hematology, Herpes zoster, Infectious diseases

Introduction

Herpes zoster (HZ), or shingles, is a cutaneous disease caused by the reactivation of latent varicella zoster virus (VZV) from dorsal root or cranial nerve ganglia, which is present due to primary infection with varicella, or chicken pox [1]. Nearly one in every three individuals will develop HZ in his or her lifetime, with approximately 1 million cases occurring each year in the United States [2, 3]. Postherpetic neuralgia is a commonly reported complication [4–6], which is a chronic neuropathic pain syndrome caused by peripheral sensory nerve damage and altered central nervous system signal processing. Postherpetic neuralgia can be severe and debilitating, and can persist 90 or more days after rash onset caused by HZ. Other severe complications of HZ include encephalitis, myelitis, cranial- and peripheral-nerve palsies, and a syndrome of delayed contralateral hemiparesis [6].

HZ is more common and often more complicated, and even life-threatening, in immunocompromised persons [7]. The conditioning chemotherapy prior to autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplants (auto-HSCT) targeting underlying malignancies causes immunosuppression, which increases patients’ risk of HZ. Within the first 12 months of post-transplantation, HZ occurs in approximately 17–50% of patients receiving allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants and 16–28% of patients receiving auto-HSCT [8, 9]. The incidence of HZ among auto-HSCT patients is 100–200/1000 person-years (PY) [9, 10] compared to 4/1000 PY in the general population [11]. Complications of HZ in auto-HSCT patients include postherpetic neuralgia, bacterial superinfection, hepatic disease, severe pain, motor weakness, neurologic dysfunction, and death [9].

Immunocompromised patients are more likely to get hospitalized [11]. Among those people who get hospitalized for HZ, about 30% of them are immunocompromised [11]. A recent study estimated that 96 HZ patients died each year in the United States; almost all deaths occurring in older adults or immunocompromised persons [11, 12].

Prophylactic antiviral therapies, such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, valganciclovir, or famciclovir, may prevent HZ infections in immunocompromised patients. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of antiviral agents in preventing HZ among immunocompromised persons [13–15]. In 2000, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) did not recommend extended AP to prevent HZ in auto-HSCT patients in consideration of increased risk of HZ after discontinuation of AP [16, 17]. However, a study by Erard et al. supported continuing AP in the post-HSCT population for up to 1 year without evidence of increased HZ risk [18]. In 2009, CDC recommended AP for 1 year in auto-HSCT patients [19]. And in 2012, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommended AP for at least 30 days to 1 year for auto-HSCT patients [20]. Prophylaxis guidelines in Europe differ from those in the United States. In 2008, the proceedings of the Second European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL) noted that routine antiviral prophylaxis of auto-HSCT patients was controversial [21]. In a 2015 update of the Guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society for Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO), routine prophylaxis with acyclovir or valacyclovir for the prevention of VZV reactivation was not recommended, but an individualized approach to prophylaxis was suggested [20].

There are no comprehensive real-world data on the duration of AP use or the risk of HZ by the duration of AP use in auto-HSCT patients in the United States. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to describe the duration of AP prescriptions and to compare the incidence of HZ by the duration of AP prescriptions in auto-HSCT patients. Data from a large health claims database were analyzed, which has the advantage of capturing both the auto-HSCT procedure and AP prescriptions filled in real-world settings.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

This was a retrospective observational study conducted in 2016. Two Truven Health MarketScan® databases were used: (1) the Commercial Claims and Encounters database and (2) the Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits database. Truven Health provides healthcare data, analytics, and consulting services for improving business and clinical outcomes. The commercial database represents approximately 100 employer-sponsored private health plans with coverage of approximately 45 million members. The Medicare Supplemental is a database of approximately 4.2 million retirees covered by their previous employers. Both databases record patient demographic data, health plan information, medical diagnosis/procedure codes, prescriptions, and cost data. Each member in the datasets has a unique identifier that can be used to track patient across the sites of service and providers, and over time. Although we do not have a visibility to what parts of Medicare (Part A, B, C and/or D) a person is enrolled in the Medicare Supplemental database, the database contains the full healthcare information (inpatient, outpatient and pharmacy) of a retiree from both Medicare and the employer-sponsored supplemental plans. Institutional review board approval was not obtained because this study was an analysis of de-identified secondary data.

Study Subjects

Auto-HSCT patients were identified by procedure codes: current procedural terminology 4th edition (CPT4) codes and International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. Subjects were included in this study if they: (1) had auto-HSCT procedure (CPT4 = 38241 or ICD-9-CM = 41.01, 41.04, 41.07, 41.09) during 2009–2013; (2) had chemotherapy (see Appendix 1 for codes to identify chemotherapy) within 60 days prior to the auto-HSCT procedure (in order to identify an uniform and consistent cohort of cancer patients undergoing induction of chemotherapy prior to the auto-HSCT procedure); the latest chemotherapy date within the 60 days prior to the auto-HSCT procedure was defined as the study enrollment date; (3) were at least 18 years old in the year of the study enrollment date; or (4) were continuously enrolled in a health plan (no gap >45 days) for at least 1 year before and after the study enrollment date. Patients who died within 1 year after the study enrollment date were kept in the study cohort. Subjects were excluded if they (1) received zoster vaccine (CPT4 = 90736 or National Drug Code (NDC) = 00006-4963-00, 00006-4963-41, or 54868-5703-00) during 1 year before or after the study enrollment date; (2) had diagnosis of HSV (herpes simplex virus, ICD-9-CM = 054.xx) or CMV (cytomegaloviral disease, ICD-9-CM = 078.5) during 1 year before or after the study enrollment date as antivirals can be prescribed to prevent or treat these conditions; (3) had diagnosis of HZ (ICD-9-CM = 053.xx) during 1 year before the study enrollment date; or (4) had a diagnosis of HZ during 7 days before or after the first AP prescription. For these patients, AP may not be prophylaxis for HZ but treatment for HZ.

Study Variable Measurements

AP Duration

Four AP drugs, acyclovir, valacyclovir, valganciclovir, and famciclovir, were included in this study. Patients were observed from 1 month before until 1 year after the study enrollment date for AP drug prescriptions. Duration of AP use was measured by total number of days supply for all filled and refilled prescriptions of all AP drugs during the observation period.

HZ Incidence

Every eligible patient was followed from the study enrollment date to the end of continuous health plan enrollment, death or December 31, 2014, whichever was the earliest to determine whether he/she developed HZ. HZ was identified by ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes (053.xx). Medically attended HZ incidence was measured as the number of HZ cases per 1000 PY. In addition to the overall medically attended HZ incidence in the auto-HSCT cohort, HZ incidence was stratified by the duration of AP prescriptions: no AP, 1–89 days, 90–179 days, 180–269 days, 270–359 days, and ≥360 days.

Other Variables

The cohort baseline characteristics were described by age, gender, geographic region of residence (Northeast, South, Midwest, West, Unknown), health plan type [Health Maintenance Organization (HMO), Exclusive/Preferred Provider Organization (EPO/PPO), point of service (POS), comprehensive, high-deductible health plan (HDHP)/consumer-driven health plan (CDHP), Unknown], and comorbidities identified by ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes during the 1 year prior to the study enrollment date: myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, zsthma, rheumatologic disease, peptic ulcer disease, liver disease, diabetes, hemiplegia or paraplegia, renal disease, and HIV/AIDS. See Appendix 2 for codes to identify comorbidities.

Statistical Analysis

This study was primarily a descriptive analysis. Descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables (e.g., gender, geographic region of residence, health plan type, and comorbidities) and mean [standard deviation (SD)] for continuous variables (e.g., age) were used to describe the characteristics of the auto-HSCT patients. HZ incidence (rate) was reported for the overall auto-HSCT cohort and by the duration of AP prescriptions. Poisson regression was used to estimate the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the HZ incidences. The association between risk of HZ and AP duration was examined by the Cox proportional hazards model after controlling for age, gender, comorbidities, AP drugs, and AP daily dosage. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

After the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, a total of 1959 eligible auto-HSCT patients were identified (Table 1). Mean age was 55.5 years (SD = 11.2); 60.0% were male (Table 2). Approximately 37.9%, 29.2%, 16.7% and 15.5% of the subjects resided in the South, North Central, West, and Northeast regions of the United States (US), respectively. Most of the study subjects had insurance coverage that was described as EPO/PPO (55.8%) with HMO, comprehensive, POS, HDHP/CDHP constituting 15.7%, 10.7%, 9.0%, 7.7%, respectively. The most common comorbidities were chronic pulmonary disease (24.9%), followed by renal disease (21.8%), diabetes (17.6%), and liver disease (10.3%).

Table 1.

Cohort construction

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria | Number of subjects |

|---|---|

| Had auto-HSCT procedure during 2009–2013 | 7213 |

| Had chemotherapy during 60 days prior to auto-HSCT procedure | 5790 |

| Age ≥ 18 years old | 5515 |

| Continuously enrolled in a health plan for at least 1 year before and after the study enrollment date | 2185 |

| Did not receive zoster vaccine during 1 year before or after the study enrollment date | 2167 |

| Did not have diagnosis of HSV or CMV during 1 year before or after the study enrollment date | 2063 |

| Did not have diagnosis of HZ during 1 year before the study enrollment date | 1972 |

| Did not have diagnosis of HZ during 7 days before or after the first AP prescription | 1959 |

Auto-HSCT autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplants, HSV herpes simplex virus, CMV cytomegaloviral disease, HZ herpes zoster, AP antiviral prophylaxis

Table 2.

Cohort characteristics

| Variable | Value | Number of subjects (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean (SD) | 55.5 (11.2) |

| Median (range) | 58 (18–79) | |

| Gender | Female | 784 (40.0%) |

| Male | 1175 (60.0%) | |

| Geographic region of residence | North central | 573 (29.2%) |

| Northeast | 304 (15.5%) | |

| West | 328 (16.7%) | |

| South | 743 (37.9%) | |

| Unknown | 11 (0.6%) | |

| Health plan typea | HMO | 307 (15.7%) |

| EPO/PPO | 1094 (55.8%) | |

| POS | 177 (9.0%) | |

| Comprehensive | 210 (10.7%) | |

| HDHP/CDHP | 151 (7.7%) | |

| Unknown | 20 (1.0%) | |

| Comorbidities | Chronic pulmonary disease | 487 (24.9%) |

| Renal disease | 427 (21.8%) | |

| Diabetes | 345 (17.6%) | |

| Liver disease | 201 (10.3%) | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 145 (7.4%) | |

| Asthma | 130 (6.6%) | |

| Congestive heart failure | 125 (6.4%) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 99 (5.1%) | |

| History of myocardial infarction | 63 (3.2%) | |

| Rheumatologic disease | 43 (2.2%) | |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 34 (1.7%) | |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 18 (0.9%) | |

| HIV/AIDS | 9 (0.5%) | |

| Dementia | 3 (0.2%) |

a HMO health maintenance organization, EPO exclusive provider organization, PPO preferred provider organization, POS point of service, HDHP high-deductible health plan, CDHP consumer-driven health plan

A total of 1821 (93.0%) patients were prescribed AP. Among those patients who received AP, acyclovir was the most common agent (78.1%), followed by valacyclovir (20.4%), famciclovir (1.4%), and valganciclovir (0.1%) (Table 3). The most common dosage prescribed was 601–800 mg (45.4%) of AP daily, followed by >1000 mg (24.1%), 401–600 mg (13.7%), 201–400 mg (7.0%), 801–1000 mg (6.8%), and ≤200 mg (3.1%). The average duration of AP prescription was 220 days (SD = 122). Only 200 (11.0%) patients had AP for ≥1 year. The percentage of patients who had AP for ≥6 months increased from 2009 (54.2%) to 2013 (69.0%) (Table 4).

Table 3.

AP drugs and duration

| Variable | Value | Number of subjects (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Receiving AP | Yes | 1821 (93.0%) |

| No | 138 (7.0%) | |

| AP drugsa | Acyclovir | 1422 (78.1%) |

| Famciclovir | 26 (1.4%) | |

| Valacyclovir | 371 (20.4%) | |

| Valganciclovir | 2 (0.1%) | |

| AP dosages | ≤200 mg | 56 (3.1%) |

| 201–400 mg | 127 (7.0%) | |

| 401–600 mg | 249 (13.7%) | |

| 601–800 mg | 827 (45.4%) | |

| 801–1000 mg | 124 (6.8%) | |

| >1000 mg | 438 (24.1%) | |

| AP durationa | Mean (SD) | 220 days (122 days) |

| Median (range) | 210 days (1–395 days) | |

| 1–89 days | 419 (23.0%) | |

| 90–179 days | 359 (19.7%) | |

| 180–269 days | 330 (18.1%) | |

| 270–359 days | 513 (28.2%) | |

| ≥360 days | 200 (11.0%) |

AP antiviral prophylaxis

aAP drugs, AP dosages, and AP durations are only for those 1821 patients who received AP

Table 4.

Percentage of patients with AP duration < and ≥180 days by year 2009–2013

| Year | n | <180 days (%) | ≥180 days (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 261 | 45.8 | 54.2 |

| 2010 | 332 | 38.0 | 62.0 |

| 2011 | 450 | 38.4 | 61.6 |

| 2012 | 413 | 32.5 | 67.5 |

| 2013 | 365 | 31.0 | 69.0 |

| Total | 1821 | 36.6 | 63.4 |

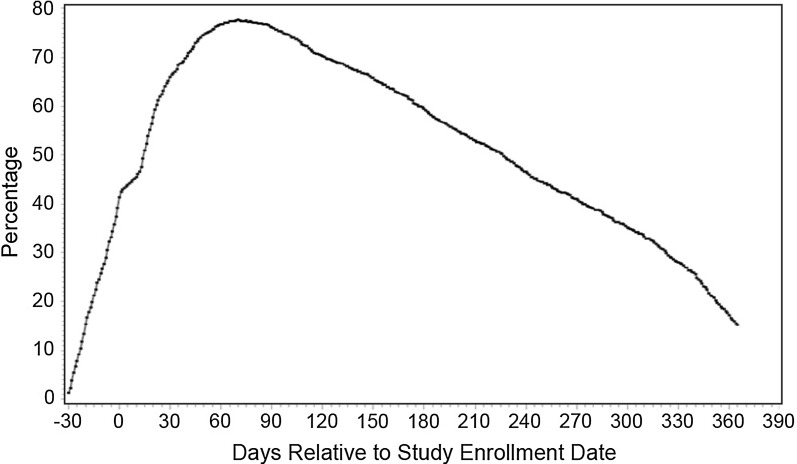

Figure 1 shows that almost 80% of the auto-HSCT patients had AP prescriptions during 60–90 days after the study enrollment date. However, by 1 year after the study enrollment date, only approximately 15% of the auto-HSCT patients had AP prescriptions.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of patients on AP from 30 days before until 1 year after the study enrollment date

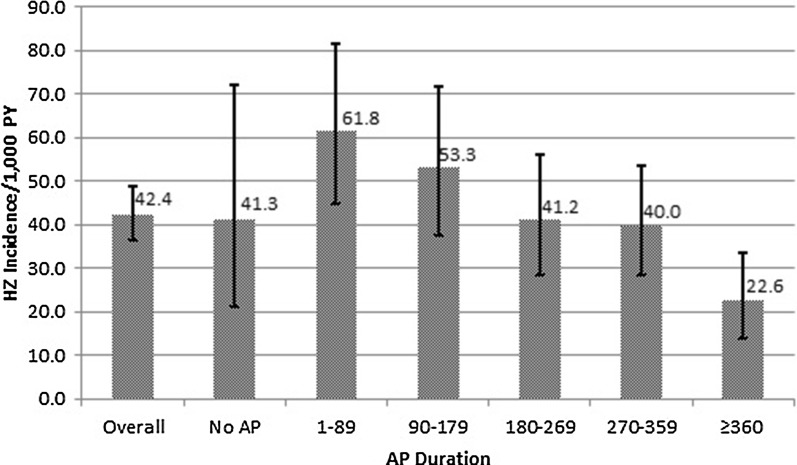

HZ incidence was 42.4/1000 PY (95% CI 36.5, 49.0) for the overall auto-HSCT cohort (Fig. 2). For those patients who did not have AP prescriptions during the first year after the auto-HSCT procedure, HZ incidence was 41.3/1000 PY (95% CI 21.3, 72.1). For those patients who had AP prescriptions during the first year after the auto-HSCT procedure, HZ incidence ranged from 61.8/1000 PY (95% CI 44.7, 81.5) for patients with AP duration of 1–89 days to 22.6/1000 PY (95% CI 13.8, 33.6) for patients with AP duration of ≥360 days.

Fig. 2.

HZ incidence by AP duration in auto-HSCT patients, 2009–2013

Table 5 suggests that, for those patients who had AP prescriptions during the first year after the auto-HSCT procedure, the risk of HZ decreases as the duration of AP prescriptions increases after controlling for age, gender, comorbidities, AP drugs, and AP daily dosage. Comparing with patients who had AP prescriptions of 1–89 days, patients with AP duration of 180–269 days [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.576, p = 0.019], 270–359 days (HR = 0.594, p = 0.023), and ≥360 days (HR = 0.309, p < 0.001) were significantly less likely to develop HZ. The risk of HZ increased as age increased (HR = 1.016, p = 0.038). Male patients had significantly lower risk of HZ than female patients (HR = 0.644, p = 0.005). Among the comorbidities, patients with a history of myocardial infarction had significantly higher risk of HZ than patients without a history of myocardial infarction (HR = 2.019, p = 0.038). The other comorbidities, AP drugs, and AP dosages were not found to be associated with the risk of HZ.

Table 5.

Association between risk of HZ and AP duration in auto-HSCT patients who received AP

| Variable | Value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP duration | 1–89 days | Reference | ||

| 90–179 days | 0.755 | 0.483, 1.182 | 0.220 | |

| 180–269 days | 0.576 | 0.364, 0.913 | 0.019* | |

| 270–359 days | 0.594 | 0.380, 0.929 | 0.023* | |

| ≥360 days | 0.309 | 0.179, 0.533 | <0.001* | |

| Age | Age | 1.016 | 1.001, 1.030 | 0.038* |

| Gender | Female | Reference | ||

| Male | 0.644 | 0.473, 0.878 | 0.005* | |

| Comorbidities | History of myocardial infarction | 2.019 | 1.041, 3.917 | 0.038* |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 1.761 | 0.422, 7.350 | 0.438 | |

| Asthma | 1.662 | 0.966, 2.862 | 0.067 | |

| Liver disease | 1.326 | 0.841, 2.093 | 0.225 | |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.282 | 0.710, 2.316 | 0.410 | |

| Rheumatologic disease | 1.239 | 0.493, 3.115 | 0.648 | |

| Renal disease | 1.143 | 0.788, 1.659 | 0.481 | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 0.924 | 0.636, 1.343 | 0.680 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.887 | 0.431, 1.824 | 0.744 | |

| Diabetes | 0.840 | 0.549, 1.286 | 0.422 | |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 0.733 | 0.177, 3.037 | 0.668 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.519 | 0.240, 1.123 | 0.096 | |

| AP drugs | Acyclovir | Reference | ||

| Famciclovir | 1.146 | 0.382, 3.436 | 0.808 | |

| Valacyclovir | 0.900 | 0.436, 1.857 | 0.776 | |

| AP dosages | ≤200 mg | Reference | ||

| 201–400 mg | 1.109 | 0.409, 3.005 | 0.839 | |

| 401–600 mg | 1.401 | 0.497, 3.947 | 0.523 | |

| 601–800 mg | 0.949 | 0.406, 2.219 | 0.904 | |

| 801–1000 mg | 0.794 | 0.251, 2.508 | 0.694 | |

| >1000 mg | 1.062 | 0.446, 2.530 | 0.892 | |

* Significant at p = 0.05

Discussion

This is the first study to use comprehensive real-world data to describe the duration of AP prescriptions and the risk of HZ by the duration of AP prescriptions in patients receiving auto-HSCT procedure. This study found that the majority (93.0%) of auto-HSCT patients received AP prescriptions during the first year after the auto-HSCT procedure. For patients with AP prescriptions, the average duration of AP was 220 days (SD = 122 days); only 11.0% of these patients had an AP duration of at least 1 year. This study found that the percentage of patients with AP duration ≥6 months increased over the study period 2009–2013, which reflects the CDC’s recommendation for extending AP to 1 year in auto-HSCT patients in 2009. For auto-HSCT patients with AP prescriptions, duration of AP prescriptions and incidence of HZ were inversely related: patients with AP prescription duration of greater than 1 year had approximately one-third the risk of HZ when compared to those with AP prescription duration of less than 3 months.

The inverse relationship between duration of AP prescriptions and incidence of HZ have also been found in other studies. Truong et al. [23] carried out a retrospective chart review study among 129 patients undergoing auto-HSCT between January 1, 2004 and January 31, 2010 to analyze rates of VZV reactivation in three different cohorts according to the length of VZV prophylaxis: (1) prophylaxis until neutrophil recovery to ≥500/μL (n = 77), (2) prophylaxis for 6 months (n = 12), or (3) 12 months (n = 40) after auto-HSCT procedure. They found that a significant reduction in rates of VZV reactivation with extended 12-month antiviral prophylaxis (2%) compared to the neutrophil recovery (14%) (p = 0.04). VZV reactivation rate in the 6-month prophylaxis group was 17%, but did not reach statistical significance due to small numbers. Kawamura et al. [24] retrospectively reviewed the clinical charts of 105 patients who underwent their first auto-HSCT between September 2007 and June 2014. Patients were divided into three groups according to the timing at which acyclovir prophylaxis was stopped after auto-HSCT: at engraftment, between engraftment and 1 year after auto-HSCT, and later than 1 year. The cumulative incidence of VZV disease was 25.8%, 7.7%, and 0.0% at 1 year, respectively.

This study found that 138 (7.0%) of the auto-HSCT patients did not have AP prescriptions during the first year after the auto-HSCT procedure. The risk of HZ among these patients appeared lower than those patients who had AP prescriptions less than 6 months and similar to those patients who had AP prescriptions between 6 months and 1 year. Patients who did not have AP prescriptions may be at lower perceived risk of HZ. For example, these patients may be VZV-seronegative or without a history of VZV infection or may have had a less immunosuppressive conditioning regimen. Further research is needed in this regard.

HZ incidence in the general population is 4/1000 PY [3]. In this study, even in those patients who received AP for more than 1 year, HZ incidence rate was 22.6/1000 PY (95% CI 13.8, 33.6), demonstrating the increased HZ risk in auto-HSCT patients even with AP prescriptions. This estimate was similar to Truong et al. [23] who found the rate of VZV reactivation with extended 12-month antiviral prophylaxis was 2% or 20/1000. It is not known whether patients took their antiviral medication or only filled their prescriptions. However, given the dose–response effect seen with HZ incidence and days supply of AP prescriptions, we assume that at least some auto-HSCT patients were compliant.

Consistent with previous studies [25–27], our study found that younger and male patients had a lower risk of HZ than older and female patients, respectively. Johnson et al. [23] found that HZ incidence monotonically increased with age from 0.86 (95% CI 0.84–0.88) for those aged ≤19 –12.78 (95% CI 12.49–13.07) for patients ≥80 years, as well as a lower HZ incidence in men compared to women (3.66%, 95% CI 3.62–3.69 vs. 5.25%, 95% CI 5.21–5.29) across all age groups. Our study also found that patients with a history of myocardial infarction had a significantly higher risk of HZ than patients who did not have a history of myocardial infarction. Further research is needed in this regard.

Limitations

Several limitations inherent to administrative claims data apply to this study. First, AP drugs that were not submitted for insurance reimbursement or received outside the network will not be captured. Furthermore, the study cohort consists of a US privately insured population, and therefore generalization may not be made beyond this population. Third, AP duration was measured by days supply recorded in pharmacy claims data, which may be underestimated if patients received AP during hospitalization. AP prescription fills and refills were taken as a surrogate for AP use in this study under the assumption that if patients received an AP prescription, they took the medicine. Fourth, this study only assessed medically attended HZ. If a patient developed HZ but did not see a doctor, he/she cannot be observed in the claims databases. In this case, HZ incidence may be underestimated. Also, HZ was based only on medical claims database information without any medical record review. Additionally, this study was not able to determine if patients were tested for VZV because laboratory data cannot be accessed. This is likely to result in some misclassification. Fifth, other confounding variables such as additional immunosuppression might increase the risk of HZ during the period after auto-HSCT procedure. With observational databases, this study was not able to control these confounding variables when examining the association between risk of HZ and AP duration. Finally, this study required patients to have at least 1 year of health plan continuous enrollment after the study enrollment date in order to examine AP use during that year. Patients who disenrolled may differ from those patients who are continuously enrolled. Non-adherence to AP prescription could be due to many reasons and maybe medically appropriate.

Conclusions

Auto-HSCT patients are at increased risk for HZ, even when prescribed AP. A substantial portion of auto-HSCT patients are provided with AP prescriptions for less than 1 year, increasing their risk of HZ and its complications. Even in those patients who received AP prescriptions for more than 1 year, the HZ incidence rate was five times that of the general population. Given the residual risk of HZ with the recommended use of antiviral prophylaxis for 1 year, and the more severe HZ complications in patients with auto-HSCT, a safe and effective vaccine against HZ in auto-HSCT patients could be a useful adjunctive prevention strategy.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Merck & Co., Inc. provided funding for the journal’s article processing charges and Open Access fee. No other funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Disclosures

Dongmu Zhang is a Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA employee and owns stock or restricted stock units of Merck & Co., Inc. Thomas Weiss is a Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA employee and owns stock or restricted stock units of Merck & Co., Inc. Yu Feng is a Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA employee. Lynn Finelli is a Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA employee and owns stock or restricted stock units of Merck & Co., Inc.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/A028F0605BF1ABF1.

References

- 1.Johnson RW, Dworkin RH. Treatment of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. BMJ. 2003;326:748–750. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7392.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Insinga RP, Itzler RF, Pellissier JM, Saddier P, Nikas AA. The incidence of herpes zoster in a United States administrative database. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:748–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Shingles (herpes zoster): Overview. http://www.cdc.gov/shingles/about/overview.html. Accessed September 15, 2016

- 4.Alper BS, Lewis PR. Treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: a systematic review of the literature. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(2):121–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baron R, Wasner G. Prevention and treatment of postherpetic neuralgia. Lancet. 2006;367(9506):186–188. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gnann JW, Jr, Whitley RJ. Clinical practice Herpes zoster. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:340–346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp013211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed AM, Brantley JS, Madkan V, Mendoza N, Tyring SK. Managing herpes zoster in immunocompromised patients. Herpes. 2007;14(2):32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su SH, Martel-Lafferriere V, Labbe A, Snydman DR, Kent D, Laverdiere M, et al. High incidence of herpes zoster in nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shuchter LM, Wingard JR, Piantadosi S, Burns WH, Santos GW, Saral R. Herpes zoster infection after autologous bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1989;74(4):1424–1427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han CS, Miller W, Haake R, Weisdorf D. Varicella zoster infection after bone marrow transplantation: incidence, risk factors and complications. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1994;13(3):277–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Shingles (herpes zoster): clinical overview. http://www.cdc.gov/shingles/hcp/clinical-overview.html. Accessed October 19, 2016

- 12.Mahamud A, Marin M, Nickell SP, Shoemaker T, Zhang JX, Bialek SR. Herpes zoster-related deaths in the United States: validity of death certificates and mortality rates, 1979–2007. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(7):960–966. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ljungman P, Wilczek H, Gahrton G, Gustavsson A, Lundgren G, Lönnqvist B, et al. Long-term acyclovir prophylaxis in bone marrow transplant recipients and lymphocyte proliferation responses to herpes virus antigens in vitro. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1986;1:185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perren TJ, Powles RL, Easton D, Stolle K, Selby PJ. Prevention of herpes zoster in patients by long-term oral acyclovir after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Am J Med. 1988;85:99–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selby PJ, Powles RL, Easton D, Perren TJ, Stolle K, Jameson B, et al. The prophylactic role of intravenous and long-term oral acyclovir after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Br J Cancer. 1989;59:434–438. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines for preventing opportunistic infections among hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report October 20, 2000; 49(RR10):1–128. [PubMed]

- 17.Sempere A, Sanz GF, Senent L, de la Rubia J, Jarque I, Lopez F, et al. Long-term acyclovir prophylaxis for prevention of varicella zoster virus infection after autologous blood stem cell transplantation in patients with acute leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1992;10:10495–10498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erard V, Guthrie KA, Varley C, Heugel J, Wald A, Flowers ME, et al. One year acyclovir prophylaxis for preventing varicella zoster virus disease after hematopoietic cell transplantation: no evidence of rebound varicella-zoster virus disease after drug discontinuation. Blood. 2007;110(8):3071–3077. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-077644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Recommendations of the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR®), the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP), the European Blood and Marrow Transplant Group (EBMT), the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation (ASBMT), the Canadian Blood and Marrow Transplant Group (CBMTG), the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Canada (AMMI), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplant recipients: a global perspective. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation. J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(10):1143–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.06.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baden LR, Bensinger W, Angarone M, Casper C, Dubberke ER, Freifeld AG, et al. Prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:1412–1445. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Styczynski J, Reusser P, Einsele H, de la Camara R, Cordonnier C, Ward KN, et al. Management of HSV, VZV and EBV infections in patients with hematological malignancies and after SCT: guidelines from the Second European Conference on Infections in Leukemi. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43:757–770. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandherr M, Hentrich M, von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Massenkeil G, Neumann S, Penack O, et al. Antiviral prophylaxis in patients with solid tumours and haematological malignancies–update of the guidelines of the infectious diseases working party (AGIHO) of the german society for hematology and medical oncology (DGHO) Ann Hematol. 2015;94(9):1441–1450. doi: 10.1007/s00277-015-2447-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Truong Q, Veltri L, Kanate AS, Hu Y, Craig M, Hamadani M, et al. Impact of the duration of antiviral prophylaxis on rates of varicella-zoster virus reactivation disease in autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients. Ann Hematol. 2014;93(4):677–682. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-1913-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawamura K, Hayakawa J, Akahoshi Y, Harada N, Nakano H, Kameda K, et al. Low-dose acyclovir prophylaxis for the prevention of herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus diseases after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2015;102:230–237. doi: 10.1007/s12185-015-1810-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson BH, Palmer L, Gatwood J, Lenhart G, Kawai K, Acosta CJ. Annual incidence rates of herpes zoster among an immunocompetent population in the United States. BMC Infect Dis. 2015 doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1262-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleming DM, Cross KW, Cobb WA, Chapman RS. Gender difference in the incidence of shingles. Epidemiol Infect. 2004;132(1):1–5. doi: 10.1017/S0950268803001523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Insinga RP, Itzler RF, Pellissier JM, Saddier P, Nikas AA. the incidence of herpes zoster in a United States Administrative Database. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(8):748–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.