Abstract

The treatment of heart failure (HF) is challenging and morbidity and mortality are high. The goal of this study was to determine if inhibition of the late Na+ current with ranolazine during early hypertensive heart disease might slow or stop disease progression. Spontaneously hypertensive rats (aged 7 mo) were subjected to echocardiographic study and then fed either control chow (CON) or chow containing 0.5% ranolazine (RAN) for 3 mo. Animals were then restudied, and each heart was removed for measurements of t-tubule organization and Ca2+ transients using confocal microscopy of the intact heart. RAN halted left ventricular hypertrophy as determined from both echocardiographic and cell dimension (length but not width) measurements. RAN reduced the number of myocytes with t-tubule disruption and the proportion of myocytes with defects in intracellular Ca2+ cycling. RAN also prevented the slowing of the rate of restitution of Ca2+ release and the increased vulnerability to rate-induced Ca2+ alternans. Differences between CON- and RAN-treated animals were not a result of different expression levels of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel 1.2, sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a, ryanodine receptor type 2, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger-1, or voltage-gated Na+ channel 1.5. Furthermore, myocytes with defective Ca2+ transients in CON rats showed improved Ca2+ cycling immediately upon acute exposure to RAN. Increased late Na+ current likely plays a role in the progression of cardiac hypertrophy, a key pathological step in the development of HF. Early, chronic inhibition of this current slows both hypertrophy and development of ultrastructural and physiological defects associated with the progression to HF.

Keywords: t-tubule, ranolazine, late INa, heart failure, calcium handling

heart failure (HF) is commonly increasing and associated with significant morbidity and mortality (19). Once established, HF is difficult to treat. An alternative approach would target patients before the onset of overt HF, during the stage when pathological cardiac changes are accumulating. Directed therapies during this vulnerable period may slow the progression to HF.

Recently, the late component of the rapid Na+ current (INa,L) has been shown to be increased in a number of models of HF (30) as well as in ischemia (10). The increase in INa,L may be responsible for the rise in intracellular Na+ concentration ([Na+]i) that has been reported in myocytes from nearly all animal models of HF, and in myocytes from human failing hearts (22, 24, 31, 32). Through reverse mode Na+/Ca2+ exchange (NCX), the rise in [Na]i leads to increased diastolic intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), which causes intracellular Ca2+ overload. The effect of INa,L to increase diastolic [Ca2+]i may cause activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) (40). INa,L-induced Ca2+ overload and activation of CaMKII are responsible for the reverse force-frequency relationship and ultimately for Ca2+ waves and triggered arrhythmias (22–24, 31, 32). An activated CaMKII may also phosphorylate voltage-gated Na+ channel 1.5 (Nav1.5), slowing Na+ channel inactivation and further increasing INa,L (16). These interesting findings about the interaction between INa,L and CaMKII raise the possibility that inhibition of INa,L could be beneficial for the treatment of HF.

T-tubule disruption is a cellular mechanism that contributes to the development of HF. It has been known for some time that t-tubule organization is decreased in nearly all animal and human models of HF (5, 7, 14, 15, 35). More recently, it has been suggested that the development of HF occurs as the number of myocytes exhibiting t-tubule disruption increases so that cardiac function declines as more myocytes are affected (4, 35). These new studies suggest that t-tubule organization plays a critical role not only in normal Ca2+ cycling but also in the development of HF, as progressively more myocytes have poor t-tubule organization.

The goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that early intervention with an inhibitor of INa,L might slow the progressive pathological changes of the myocardium (e.g., t-tubule disruption and Ca2+ cycling defects) that lead to HF. Spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs; 7 mo old) were randomly assigned to control (CON; no drug) or ranolazine (RAN) treatment groups for 3 mo. The 3-mo treatment with the INa,L inhibitor ranolazine (RAN) (3, 6) was intended to serve as a proof of concept that inhibition of INa,L at an early stage of hypertension-induced hypertrophy could delay or prevent the development of HF.

METHODS

Male SHRs (7 mo of age, 2 groups of 8 each) were used in this study. Ionic current was measured in an additional 6 SHRs (3 each at 7 and 10 mo of age). Animal use protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee according to National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines. Each group of animals was studied using echocardiography and then either maintained on normal chow (CON) or started on chow containing 0.5% RAN. The mean plasma RAN concentration measured in RAN-treated rats at the end of the study was 5.4 ± 0.5 μM, a value that is within the therapeutic range (2–8 μM). After 3 mo, a repeat echocardiogram was performed. There were no significant differences in body weight, heart weight, heart weight-to-body weight ratio, heart rate, or systolic and diastolic blood pressures of rats in the CON and RAN groups at the time of study termination. After completion of the echocardiogram, each heart was then removed, perfused using the method of Langendorff to wash out pretreatment drug or vehicle, and used for imaging studies.

Imaging of t-tubule organization and intracellular Ca2+ cycling.

A Langendorff-perfused heart was placed in an experimental chamber on the stage of a Zeiss LSM510 laser scanning confocal microscope and then exposed to the membrane potential-sensitive dye 4-{β-[2-(di-n-butylamino)-6-naphthyl]vinyl}pyridinium (di-4-ANEPPs; 8–10 μM) during recirculation with modified Tyrode solution at a temperature of 25 ± 1°C. Cytochalasin-D (60 μM) and blebbistatin (20 μM) were then added to the perfusate to abolish contraction. Three-dimensional images of t-tubule organization were recorded in 20–25 subepicardial regions of the left ventricular (LV) free wall using a ×40 (numerical aperature, 1.2) water immersion objective. T-tubule organization was recorded in at least 100–200 myocytes for each heart. The dye-containing solution was then washed out by perfusion of the heart with fresh Tyrode solution for 10 min, after which recirculation was initiated again with buffer containing fluo-4 AM (15 μM). Two successive additions of 12 and 10 μM fluo-4 AM to the perfusate were made after 20 and 40 min. The fluo-4 AM solution was then washed out to allow deesterification of the dye in the cytoplasm. Recirculation was reinitiated and the paralytic agents were again introduced into the solution.

Ca2+ imaging was accomplished as previously described (1, 12, 33, 34). Briefly, the scan line was placed either along the long axis of individual myocytes to obtain high resolution imaging of Ca2+ cycling within a single cell or the line was placed across the short axis of multiple cells (up to ∼14) to study Ca2+ cycling in larger cell populations. Multiple sites were imaged in the middle of the LV free wall to get a random sampling of Ca2+ cycling behavior among many myocytes in each heart. Note that kinetics of intracellular Ca2+ changes but not amplitude can be reliably measured in hearts previously exposed to di-4-ANEPPS, because although interference by di-4-ANEPPS affects the absolute levels of fluo-4 fluorescence intensity, it does not alter the relative changes.

In some of the control-fed SHRs, we identified myocytes with defective Ca2+ cycling (slow rise, low release, and slow decay). RAN (10 μM) was then added to the superfusate, and these multicellular sites were imaged after 10 min of exposure to RAN.

Because we were interested in both the release and recovery phases of sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ cycling, we analyzed rise time (i.e., from 10 to 90% of the peak) and time to peak Ca2+ (i.e., from baseline to 100% of the peak) transient and transient durations at 50, 80, and 90% (TD50, TD80, and TD90, respectively) of recovery to baseline. A customized MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA) routine was used for measurements of Ca2+ transients during pacing at a basic cycle length (BCL) of 700 ms and during rapid pacing (BCL = 300 ms) to allow comparisons of Ca2+ cycling at both slow and fast heart rates. In addition, restitution of SR Ca2+ release was measured following a 30-s train at the basal pacing cycle length of 700 ms by interpolating a single beat at an interval ranging from 150 to 600 ms. Restitution as a function of increasing recovery interval was calculated by measuring Ca2+ transient magnitude as percentage of that observed at the basal rate. The magnitude of Ca2+ alternans (cycle-to-cycle “large-small-large-small” alternations in Ca2+ transient magnitude) was measured at the end of a 10-s period of rapid pacing at progressively shorter BCL from 400 to 180 ms, following 30 s of pacing at the basal rate. Alternans ratio (AR) was calculated as a measure of the variation of the beat-to-beat Ca2+ transient amplitude [AR = 1 − (small/large)] (39). Note that AR ≈ 1 signifies a nearly undetectable Ca2+ transient during the small alternation. Finally, the variability in Ca2+ cycling properties within each myocyte was measured as the SD of measured values of each property.

Measurements of t-tubule organization using a fast Fourier transform.

The two-dimensional (2-D) image from each z-stack that represented the middle of each myocyte excluding the external sarcolemma was identified and analyzed using customized MATLAB software and then transformed to the spectral domain using a fast Fourier transform. Power spectrum analysis was used to determine an index of t-tubule organization (OI) within a myocyte (9, 28). To increase the sensitivity of our calculation of t-tubule organization, we measured the area under the power spectrum between frequencies 0.43 and 0.53 μm−1 where normally organized t-tubules would be found (band 1, which peaks at a power of ∼0.46 μm−1). We then measured the area under the power spectrum between frequencies 0.33 and 0.43 μm−1 where poorly organized t-tubules would be evident (band 2). All power below 0.33 μm−1 was ignored because this component contains only system noise. OI was calculated as the power for organized t-tubules as a fraction of the total power of both poorly organized and normal t-tubules [band 1/(band 1 + band 2)]. This approach provides a sensitive measure of both the decrease in well-organized t-tubules as well as the increase in poorly organized t-tubules, giving a usable range of ∼0.45 to 0.95. OIs were measured for all cells in each heart to compare the effects of RAN versus CON. In these analyses, OI can decrease but cannot increase beyond a maximum, resulting in a naturally skewed rather than a normal distribution of OI values. Therefore, 95% confidence intervals for OI were used as a measure of variability in OI. Note, however, that mean and SD are also included because it will be the OI mean and the variability around the mean that will ultimately determine the physiological effect of OI variability in the whole heart.

Echocardiography.

Echocardiography (2-D and M-mode) was performed on each animal at baseline (7 mo), and after 3 mo of treatment. animals were restrained and tail blood pressure was measured with a CODA System (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT). All animals were imaged by a single, experienced echocardiographer using an i13L probe and a Vivid 7 echocardiography machine (General Electric). Short-axis, long-axis, and apical four-chamber views of the heart were obtained. LV mass, dimensions including LV end-diastolic diameter, fractional shortening, and ejection fraction were quantified, along with mitral inflow parameters. All measurements were made offline using an EchoPAC workstation (General Electric, Kenosha, Wisconsin).

Measurement of INa,L in isolated LV myocytes from 7- and 10-mo-old SHR.

Briefly, 7- and 10-mo-old male SHRs were anesthetized and anticoagulated with heparin sodium. Hearts were removed and immediately mounted on a Langendorff apparatus to be perfused at 8 to 9 ml/min and 37°C with a solution of the following composition: (in mM) 140 NaCl, 4.4 KCl, 1.5 MgCl2, 120 NaH2PO4, 5 HEPES, 7.5 glucose, 16 taurine, and 5 Na pyruvate, adjusted with NaOH to pH 7.3. Hearts were then perfused with this solution supplemented with collagenase type I (0.8 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 0.2% bovine serum albumin. The LV free wall was dissected and finely chopped and gently triturated. Isolated myocytes were collected by filtration and stored in Kraftbrühe solution for 1 h at room temperature and then transferred to Eagle's minimal essential medium solution (M0518; Sigma-Aldrich), supplemented with (in mM) 1 Ca2+, 5 HEPES, and 5 glucose at pH 7.3 (NaOH). Isolated cardiomyocytes were used within 6–8 h after isolation.

Whole cell INa was recorded at 22 ± 1°C using the patch-clamp technique and a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Cardiomyocytes were superfused with bath solution containing (in mM) 135 NaCl, 4.6 CsCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.1 MgSO4, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose and 0.01 nitrendipine at pH 7.4. Patch pipettes were made from borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) using a DMZ Universal puller (Dagan, Minneapolis, MN). Pipette resistance was 1–2 MΩ when filled with a pipette (internal) solution containing (in mM): 120 aspartic acid, 20 CsCl, 1 MgSO4, 4 ATPNa2, 0.1 GTPNa3 and 10 HEPES; pH adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH. After establishing a whole cell patch configuration, a period of 5–10 min was given for cells to stabilize before conducting experiments. INa,L was measured as current amplitude between 210 and 220 ms after application (at a rate of 0.1 Hz) of a 220-ms depolarizing step to −20 mV from a holding potential of −120 mV. Data were acquired using pClamp 10.2 software (Molecular Devices) and analyzed using Clampfit 10, Microcal Origin (OriginLab, Northampton, MA), and GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) software programs. Values of INa,L in the absence and presence of RAN were corrected by subtraction of tetrodotoxin (10 μM)-insensitive current. To determine the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for inhibition by ranolazine of INa,L, concentration-response relationships were fit using the Hill equation: Idrug/Icontrol = 1/[1 + (D/IC50)nH], where Idrug/Icontrol is fractional block, D is drug concentration, IC50 is the drug concentration that causes 50% block, and nH is the Hill coefficient.

Protein lysate preparation and Western blot analysis.

Protein lysates were prepared by resuspending the frozen tissue in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (pH 7.4) containing 1% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) and 1× protease inhibitors (Complete Mini, Roche) on ice. The tissue was homogenized on ice using six brief pulses of a polytron homogenizer. Homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000 g for 20 min at 4°C to remove pellet. The supernatant was used for Western blot analysis. Cell lysates were heated with Laemmle sample buffer, consisting of 0.5 mM Tris·HCl (pH 6.8), 10% SDS, 10% glycerol, 4% β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.05% bromophenol blue at 55°C for 15 min. Equal amounts of protein (40 μg/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE (4–20% gradient gel, Bio-Rad) and electroblotted on polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were blocked using either 5% BSA or 5% nonfat skim milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20. Antibodies against voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel 1.2 (Cav1.2; 1:1,000, Abcam), NCX (1:500, Swant Swiss antibodies), sarco(endo) plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a (SERCA2a; 1:200, Thermo Scientific), Nav1.5 (1:1,000, Alomone) and ryanodine receptor type 2 (RyR2; 1:500, Thermo Scientific) were incubated with the membranes overnight at 4°C. The membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies for 2 h at 37°C. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Protein bands were visualized with ECL-Plus reagent (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Band intensity was quantified by densitometric scanning with ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Statistics.

Data are presented as means ± SE unless otherwise indicated. Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot 11.0. Sample means were compared between groups using either paired or unpaired t-tests, and ANOVA was used for comparisons for multiple groups with Student-Newman-Keul's tests for post hoc comparisons. Differences between sample means were considered significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Chronic INa,L block (3 mo) decreases the number of myocytes with poor t-tubule organization.

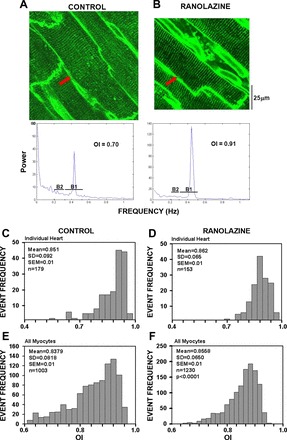

The OI was measured as a fluorescence signal from di-4-ANEPPs staining of the t-tubule membrane, excluding the sarcolemma. Results of OI measurements are shown in Fig. 1. Figure 1A shows a myocyte from a CON heart with poor t-tubule organization, whereas Fig. 1B shows a cell from a RAN heart with highly organized t-tubules. The graphs below each 2-D image illustrate the results of the fast Fourier transform where the CON cell has a small peak and a high baseline to the left of the peak, indicating both an increase in poorly organized t-tubules and a decrease in well-organized t-tubules. In contrast, the RAN cell has a very sharp, high-peak and a very low baseline, indicating that virtually all fluorescence is found only in the highly organized t-tubule system.

Fig. 1.

Measurements of t-tubule organization index (OI) in myocytes from hearts of control- and ranolazine-fed rats. A and B: example 2-dimensional images of a cardiac myocyte from a control (A) and a ranolazine-treated (B) rat. The graphs below each panel show the fast Fourier transform (frequency on the x-axis; power on the y-axis) for each cell indicated with a red arrow in the images. The frequency range for bands 1 and 2 (B1 and B2, respectively) is indicated for calculation of OI, as described in methods. C and D: frequency (y-axis) histograms showing examples of measurements of OI (x-axis) in cardiomyocytes from individual control- and ranolazine-fed rats. E and F: summary data for all myocytes (n = 1,003 and 1,230 for control and ranolazine, respectively) from all hearts (n = 8 rats in each group).

OI distributions from representative CON and RAN hearts are illustrated in Fig. 1, C and D, respectively. For the CON rat heart (Fig. 1C), the mean OI for all myocytes was 85.1 ± 10.0% (OI = 0.851) with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 65.5 to 104.7%. Note the distinct skewing of the distribution to the left, indicating a significant number of myocytes with poor t-tubule organization. In contrast, the RAN heart (Fig. 1D) has a slightly higher mean OI (86.2 ± 10.9%) with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 66.6 to 105.8%.

Fig. 1, E and F, shows the cumulative OI histograms for all CON and RAN rats (n = 8 for each group), respectively. The mean OI for all CON myocytes was 83.8 ± 8.2% (OI = 0.838, n = 1,003 cells in 8 hearts) with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 83.3 to 84.3%. Note the distinct skewing of the distribution to the left. In contrast, myocytes from all RAN hearts had a higher mean OI (85.6 ± 1.9%, n = 1,230 in 8 hearts, P < 0.001 compared with CON), with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 85.2 to 85.9%. In addition, the percentage of myocytes with OI ≤ 80% was significantly lower in hearts from RAN-treated compared with CON rats (14 ± 3.0% vs. 37 ± 10%, P < 0.05). These data demonstrate that not only is there a significantly greater OI in the myocytes from RAN hearts but there are also fewer myocytes with poorly organized t-tubules in the RAN hearts compared with CON hearts.

Chronic INa,L block prevents the progression of LV hypertrophy.

Echocardiographic measurements before and after 3 mo of CON and RAN feeding are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences in cardiac structure and function (e.g., LV end-diastolic diameter, fractional shortening, ejection fraction) between CON and RAN-fed rats, with the exception of LV mass. Hearts from CON rats had the expected increase in LV mass from 7 to 10 mo (+0.13 ± 0.12 g), whereas LV mass in RAN rats declined (−0.06 ± 0.11 g, P = 0.005 vs. CON).

Table 1.

Summary of values of structural and functional parameters measured using echocardiography in control- and ranolazine-treated rats

| Control |

Ranolazine |

Difference, 10 vs. 7 mo |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echo Trait | 7 mo | 10 mo | P value | 7 mo | 10 mo | P value | Control | Ranolazine | P value |

| LV mass, g | 1.05 ± 0.07 | 1.18 ± 0.08 | 0.018 | 1.14 ± 0.09 | 1.08 ± 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.13 ± 0.12 | −0.06 ± 0.11 | 0.005 |

| LVEDD, mm | 7.80 ± 0.53 | 7.50 ± 0.21 | 0.15 | 7.84 ± 0.79 | 7.40 ± 0.40 | 0.20 | −0.31 ± 0.54 | −0.44 ± 0.87 | 0.73 |

| EF, % | 83 ± 3 | 84 ± 5 | 0.76 | 84 ± 5 | 84 ± 6 | 0.84 | 0.8 ± 6.7 | 0.6 ± 8.3 | 0.97 |

| FS, % | 47 ± 3 | 49 ± 7 | 0.56 | 48 ± 6 | 48 ± 7 | 0.97 | 1.8 ± 8.0 | −0.13 ± 10.2 | 0.69 |

| E/A ratio | 1.99 ± 0.28 | 1.89 ± 0.30 | 0.49 | 1.64 ± 0.25 | 2.01 ± 0.36 | 0.077 | −0.11 ± 0.40 | 0.38 ± 0.42 | 0.054 |

Values (means ± SE) were collected before (age of 7 mo) and after (10 mo) feeding of spontaneously hypertensive rats with either normal chow (control) or chow containing ranolazine for 3 mo (n = 8 rats in each group). LV, left ventricular; LVEDD, LV end-diastolic diameter; EF, ejection fraction; FS, fractional shortening; E/A, ratio of the early (E) inflow of blood to the left ventricle through the mitral valve upon its opening, to the subsequent peak of the atrial (A) contraction-induced inflow of blood.

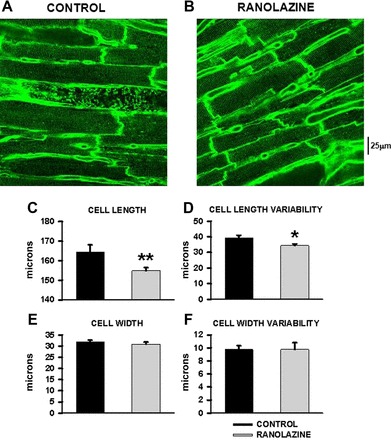

We also measured cell size characteristics that are associated with hypertrophy. Representative images in Fig. 2, A and B, show that cell length but not cell width was greater in the CON heart than following RAN treatment. The summary data show that cell length (measured in cells at rest) but not cell width was significantly greater in CON- than in RAN-treated rats at 10 mo (Fig. 2, C and E). The variability in cell length but not in cell width was also significantly greater in hearts from RAN-treated compared with CON-treated rats (Fig. 2, D and F).

Fig. 2.

Summary of data for mean cardiomyocyte cell length and width in control- and ranolazine-fed spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs). A: 2-dimensional image of myocytes from a control heart. B: image of a ranolazine heart. C: summary of mean cell length. D: summary of variability (SD) of cell length. E: mean cell width. F: variability of cell width in hearts from control- (black bars) and ranolazine-fed (light gray bars) rats. N = 1,024 and 1,234 myocytes from 8 hearts in each group. *P < 0.05 vs. control; **P < 0.01 compared with control.

Chronic RAN treatment prevents the development of Ca2+ cycling defects during the progression of hypertensive heart disease.

An essential characteristic of altered Ca2+ cycling in HF is a slowing in Ca2+ release and reuptake (14, 34). The former occurs presumably because t-tubule disruption reduces Ca2+ influx via L-type Ca2+ channels and thus reduces the trigger for Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from the SR. This is primarily responsible for systolic dysfunction as slow, nonuniform, and defective Ca2+ release throughout the myocyte leads to slow and inefficient myofibril activation and resulting cell contraction. Prolongation of the Ca2+ transient occurs in part because of reduced expression of SERCA2a, thereby slowing Ca2+ reuptake. However, even if Ca2+ removal mechanisms were normal, the delayed Ca2+ release in itself results in extended reuptake. This slowing in relaxation is likely to contribute to diastolic dysfunction.

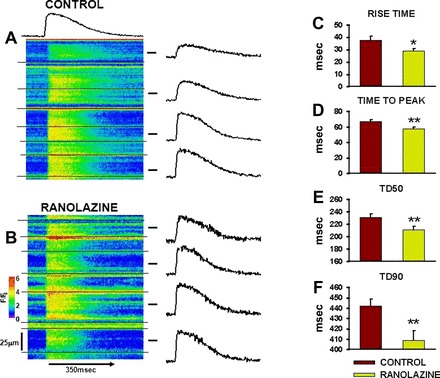

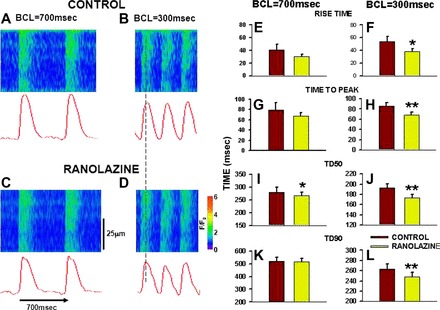

Figure 3 shows transverse line scan recordings across many cells in intact hearts of both 10-mo-old CON (A)- and RAN (B)-fed animals. The BCL for pacing was 700 ms. The transverse scan mode facilitates simultaneous measurement of Ca2+ transients in multiple myocytes. Note that the black horizontal lines indicate cell edges; thus Fig. 3A shows recordings from seven myocytes, and Fig. 3B shows recordings from six cells. Average fluorescence intensity is shown in the intensity profile above each line scan. On the right are intensity profiles from four selected myocytes from each image. The cells in the CON heart generally show a slower rise and delayed time to peak as well as slower decay to diastolic Ca2+ levels than the myocytes in the RAN heart. The summary data in Fig. 3, C–F, show that there is a faster rate of Ca2+ release (shorter rise time) in myocytes from RAN-fed animals and shorter overall time to peak release. The durations of Ca2+ transients at both 50 and 90% of recovery (TD50, TD90) were also significantly shorter in the RAN than in the CON heart (Fig. 3, E and F).

Fig. 3.

Calcium transients in myocytes of hearts from control- and ranolazine-fed rats. A: line scan image across multiple cells in an intact heart from a control rat. Horizontal black lines indicate cell boundaries. Average intensity profile for the entire site is shown above the image. Intensity profiles for selected myocytes are shown to the right of the image. B: line scan image from a ranolazine heart. F/F0, fluorescence intensity ratio. C–F: summary data for Ca2+ transient rise time, time to peak, and durations at 50 and 90% recovery (TD50 and TD90, respectively) to baseline in myocytes from control- (red bars) and ranolazine-fed (green bars) rats. n = 72–146 myocytes in 3 hearts each. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with control.

Chronic block of INa,L increases synchrony of Ca2+ cycling within the myocyte.

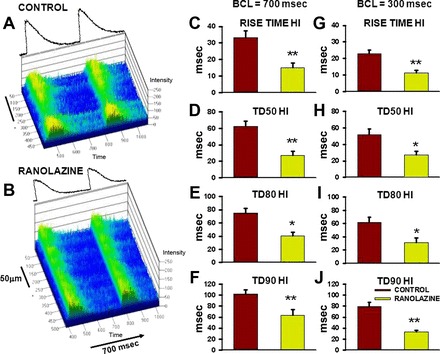

In addition to improving overall Ca2+ cycling properties (rates of Ca2+ release and removal), RAN also prevented the loss of synchronization in Ca2+ cycling within the myocyte. Figure 4, A and B, shows line scan images of Ca2+ transients recorded along the length of individual myocytes in intact hearts of CON and RAN SHRs during basal pacing at BCL = 700 ms. Note that the Ca2+ transient is more variable along the cell length (rise time, magnitude, and duration) in the myocyte from CON than from the RAN-fed rat. Ca2+ cycling was then analyzed in 2-μm increments along the entire cell length, approximating the length of individual sarcomeres, and the SDs of individual parameters were calculated to measure variability in Ca2+ release and reuptake along the cell length during both basal (BCL = 700 ms) and rapid pacing (BCL = 300 ms). Values of SD for Ca2+ release (rise time, Fig. 4, C and G) and for duration of the Ca2+ transient at 50, 80, and 90 of recovery (TD50, TD80, TD90; Fig. 4, D–F and H–J) were significantly decreased at both heart rates in the RAN myocytes compared with CON. These results indicate that the increased variability in Ca2+ cycling in CON is reduced by RAN and that this effect was independent of heart rate.

Fig. 4.

Variability in Ca2+ cycling along the cell length in myocytes in intact hearts from control- and ranolazine-fed rats. A and B: line scan images of Ca2+ transients in individual myocytes recorded longitudinally from intact hearts of control and ranolazine treated rats, respectively, during pacing at a basic cycle length (BCL) of 700 ms. Average fluorescence intensity profiles are shown above each image. C–J: heterogeneity indexes (HIs; i.e., values of SD) of mean values of rise time, TD50, TD80, and TD90 of Ca2+ transients recorded in cardiomyocytes from control- (red bars) and ranolazine-fed (green bars) rats during pacing at BCL = 700 (left) and 300 ms (right). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 compared with control.

Chronic RAN treatment prevents the increased vulnerability to rate-dependent Ca2+ alternans found in HF.

We recently reported a shift in the rate dependence of Ca2+ alternans to much slower heart rates during the progression of HF in the SHR model; this shift parallels disease development and aging (11, 34). The result is that Ca2+ alternans develops at progressively slower heart rates during HF development, making these hearts more vulnerable to reentrant arrhythmias. Alterations of Ca2+ release from the SR feedback on Ca2+-sensitive sarcolemmal ionic currents and exchangers such as the L-type Ca2+ channel current and the NCX current to increase the temporal variability of action potential duration (APD) (25, 26), which in turn establishes ventricular repolarization gradients and therefore reentrant arrhythmias (36).

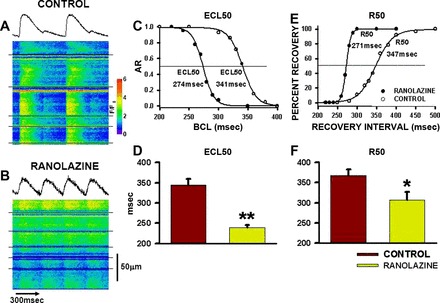

Figure 5 shows transverse line scan recordings of multiple myocytes in two intact hearts during four paced beats at a BCL = 300 ms. There was nearly complete Ca2+ alternans in the myocytes from the CON heart (note average intensity profile above the image; Fig. 5A). In contrast, none of the myocytes in the RAN heart in Fig. 5B demonstrates Ca2+ alternans. Figure 5C shows the rate dependence of alternans development for myocytes from a RAN heart (black circles) and a CON heart (white circles). Note that Ca2+ alternans magnitude is calculated as alternans ratio so that alternans magnitude increases with decreasing BCL (increasing heart rate). The estimated cycle length at 50% alternans (ECL50) was 341 ms in the CON heart compared with 274 ms in the RAN heart. The data summarized in Fig. 5D for all myocytes of each type depict a significant increase in vulnerability to Ca2+ alternans (shift of ECL50 to longer cycle lengths) found in hearts of CON- relative to RAN-treated rats.

Fig. 5.

Calcium alternans and restitution of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release in myocytes in hearts of control- and ranolazine-fed rats. A and B: line scan images across multiple cells in hearts of control- (A) and ranolazine-fed (B) rats during pacing at BCL = 300 ms. Cells are separated by horizontal black lines. C: relationship between the magnitude of the alternans ratio [AR = 1 − (small/large)] and BCL in hearts from control- (○) and ranolazine-fed (●) rats. ECL50 is the estimated cycle length at which AR = 0.5. D: summary of ECL50 data for all myocytes [n = 11 and 16 in 3 hearts each from control- (red bar) and ranolazine-fed (green bar) rats]. E: recovery of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release as a function of recovery interval. R50 is the cycle length at 50% recovery of Ca2+ transient magnitude (relative to magnitude recorded at a BCL of 700 ms). F: summary of R50 data for all myocytes [n = 7 and 16 in 3 hearts each from control- (red bar) and ranolazine-fed (green bar) rats]. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with control.

We have proposed that the Ca2+ cycling instabilities responsible for Ca2+ alternans development may be related to a slowing in the rate of recovery (restitution) of SR Ca2+ release as heart rate increases (32). The rate of restitution of Ca2+ release in a CON myocyte is shown in Fig. 5E; the 50% recovery interval (R50) was 347 ms. This rather long recovery interval is consistent with findings that we have previously reported for the SHR (11, 34). The recovery interval was much shorter in a myocyte from a RAN heart (R50 = 271 ms), demonstrating that the slowing in the recovery of SR Ca2+ release during HF development in the SHR was prevented by RAN treatment. The summary histogram in Fig. 5F shows that SR Ca2+ release restitution in RAN-treated SHR was faster than in CON-treated SHR.

Acute INa,L block increases Ca2+ release rate and Ca2+ reuptake rate in HF myocytes.

In three CON hearts (n = 9 myocytes), we added RAN to the superfusate to investigate its acute effects on Ca2+ cycling in 10-mo-old SHRs. Figure 6, A and B, shows transverse line scan images from a cell in an intact CON heart at BCLs of 700 and 300 ms, respectively. Note that the rise time of the Ca2+ transient is slow at BCL = 700 ms, giving a rounded appearance to the Ca2+ transient; this was exaggerated during faster pacing (and consistent with results summarized in Fig. 3). RAN (10 μM) was added to the superfusate for 10 min and recordings were repeated at both cycle lengths. Note the faster Ca2+ release at both BCL = 700 and 300 ms (Fig. 6, C–H) in the presence of RAN. The vertical line drawn between the recordings at the faster rate indicates the time at which peak magnitude of the Ca2+ transient is achieved during RAN treatment. The time at which peak fluorescence occurs after RAN exposure is earlier than peak release before RAN treatment. The summary data in Fig. 6, E–L, show that the rate of Ca2+ release (rise time, time to peak) is increased by RAN during rapid pacing and that the slow Ca2+ reuptake in HF is accelerated by RAN, again with a greater effect during rapid pacing. These data demonstrate that, in addition to chronic effects to slow the onset of Ca2+ cycling defects, acute exposure to RAN also increases the rates of Ca2+ release and reuptake, which are underlying determinants of systolic and diastolic function.

Fig. 6.

Effects of acute ranolazine treatment on Ca2+ transient characteristics during slow (BCL = 700 ms) and rapid (BCL = 300 ms) pacing. A and B: line scan images showing Ca2+ transients in a control rat heart at BCL = 700 and 300 ms. Intensity profile is shown below. C and D: recordings from the same heart as in A and B after 10 min of exposure to ranolazine (10 μM). E–L: summary data for Ca2+ transient characteristics before (red bars) and after 10 min exposure to ranolazine (green bars). n = 9 myocytes in 3 hearts. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with control.

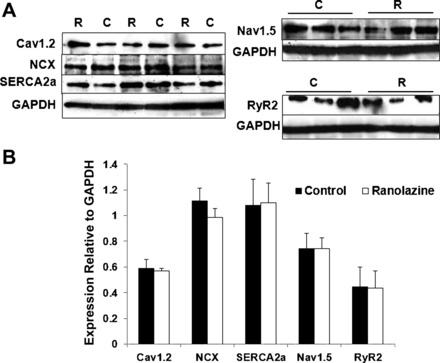

Effects of chronic INa,L block on expression of Ca2+ cycling proteins.

We further investigated whether ranolazine has any potential effect on the expression level of different Ca2+ handling proteins essential to excitation-contraction coupling. Protein lysates were obtained from LV tissue from both CON (n = 4) and RAN rats (n = 5). We quantified Cav1.2, NCX, SERCA2a, Nav1.5, and RyR2 protein levels. Figure 7 shows that expression of these proteins was not significantly changed in hearts from rats treated with RAN compared with CON animals. Thus any differences between the experimental groups must occur as the result of RAN treatment that does not involve changes in expression levels of these proteins.

Fig. 7.

Expression of Ca2+ cycling proteins in left ventricular tissue from rats-fed control (C) or ranolazine-containing (R) chow for 3 mo. A: Western blot showing expression of voltage-dependent Ca2+ 1.2 (Cav1.2), Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX), sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a (SERCA2a), voltage-gated Na+ channel 1.5 (Nav1.5), and ryanodine receptor type 2 (RyR2), with GAPDH as control. B: relative protein expression normalized to GAPDH in hearts from control- (black bars) and ranolazine-fed (white bars) rats. Values indicate means ± SE; n = 4 for C and n = 5 for R.

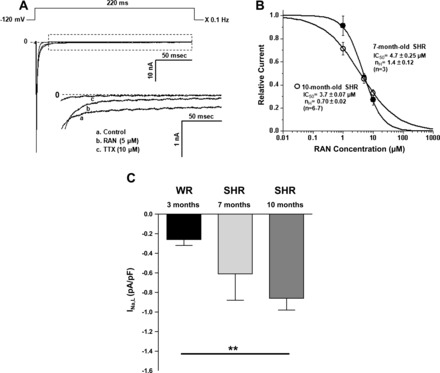

Ranolazine block of INa,L in SHRs at both 7 and 10 mo of age.

Finally, we made direct measurements of INa,L in SHR myocytes to determine the magnitude of the current and whether this current is blocked by relevant concentrations of ranolazine. Figure 8A shows a representative recording of INa,L and the effects of RAN to reduce this current followed by complete block with tetrodotoxin. The concentration-response relationships for ranolazine (Fig. 8B) show that the IC50 values for block of INa,L by RAN were 3.7 ± 0.01 and 4.7 ± 0.25 μM in myocytes from 7- and 10-mo-old rat hearts, respectively (P = not significant). These data demonstrate that the 5.4 μM concentration of RAN found in the plasma of RAN-treated rats was likely to have caused significant block of INa,L in myocytes from SHRs used in this study. Finally, the magnitudes of INa,L were significantly different between LV myocytes from hearts of 3- to 4-mo-old Wistar and 10-mo-old SHRs (Fig. 8C, **P < 0.01).

Fig. 8.

Measurements of late sodium current (INa,L) in cardiac myocytes isolated from 7- and 10-mo-old SHRs. A: voltage-clamp protocol (top) along with representative recordings of total and late (INa,L) sodium current from a single myocyte (10-mo-old SHR) in the absence (control) and presence of sodium channel blockers ranolazine (RAN, 5 μM) and tetrodotoxin (TTX, 10 μM). Inset: expanded tracings of INa,L. Test potential was −20 mV. B: concentration-response relationships for inhibition by ranolazine of INa,L in 7- (●) and 10-mo-old (○) SHRs. nH, Hill coefficient. C: summary of normalized INa,L magnitude in 3-mo-old Wistar rats (WRs, n = 9), 7-mo-old SHRs (n = 4) and 10-mo-old SHRs (n = 7). nH **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Recently, it has been suggested that the development of HF occurs as the result of the accumulation of myocytes with disrupted t-tubules (4, 5, 34, 35). Disorganization of the t-tubule network is at least partially responsible for the defects in intracellular Ca2+ cycling and contractile function characteristic of myocytes in HF. When the number of myocytes with poorly organized t-tubules is low, there is very little change in cardiac performance. However, as the number of myocytes with disrupted t-tubules increases, paralleled by a decrease in the number of myocytes with normal t-tubule organization and cell function, there will be a progression from a compensated hypertrophic stage to decompensated HF (35). This process progresses with time until there are too few normal myocytes, too many myocytes with defective t-tubules (both ultrastructurally and functionally), and eventually replacement of dead myocytes with fibrotic tissue.

The goal of the experiments in the present study was to determine if block of INa,L might slow the progression to HF in a hypertension-induced model of cardiac hypertrophy. The major finding was that treatment of 7-mo-old SHR for 3 mo with ranolazine, an inhibitor of INa,L, reduced the percentage of cardiac myocytes with poor t-tubule organization (i.e., those with an OI of 0.8 or lower; Fig. 1), shortened the duration and the longitudinal variability of the Ca2+ transient in individual myocytes (Figs. 3, 4), reduced rate-dependent Ca2+ alternans (Fig. 5), and improved the restitution of SR Ca2+ release (Fig. 5), compared with untreated control rats. Thus ranolazine improved the stability and synchrony of cellular Ca2+ handling, especially at a high rate (BCL = 300 ms) of pacing. These findings are consistent with previous reports that ranolazine reduces Na+/Ca2+ overloading and occurrences of delayed afterdepolarizations in myocytes from failing hearts (30). The findings suggest that inhibition of late INa during the development of cardiac hypertrophy and failure may be beneficial to reduce both the progressive loss of t-tubule organization and the increase of contractile and rhythm disturbances.

There is growing evidence that INa,L is increased and contributes to electrical instability (arrhythmias) and LV diastolic dysfunction in HF and during ischemia (6, 17, 30). We also found that the amplitude of INa,L in this study was greater in LV myocytes from SHRs than in control rats. It has been suggested that CaMKII is activated (possibly by increased diastolic [Ca2+] or reactive oxygen species) and then phosphorylates Na+ channels, resulting in an increase in INa,L (16). The reverse may also be true, namely, that an increase in INa,L raises [Na+]i and therefore [Ca2+]i, which in turn activates CaMKII (40). Regardless of how INa,L is enhanced, the result would be the intracellular accumulation of Na+, which has been identified in nearly all forms of HF in both animal models and in patients (22–24, 31, 32). An increase in Na+ would in turn lead to a further increase in intracellular Ca2+ via reverse-mode NCX, increasing Ca2+ uptake into the SR, but because of increased SR Ca2+ leak in HF (13), failing to increase SR Ca2+ load while maintaining an increased diastolic Ca2+. This idea is supported by the fact that inhibition of INa,L improved Ca2+ cycling defects and diastolic relaxation of contractile force in this and previous (30, 31) studies.

From a more global perspective, it is interesting that there were no significant changes in myocardial mechanics in control SHRs as measured using advanced echocardiographic imaging over the 3-mo period of study. Systolic and diastolic functions were unchanged despite clear evidence of t-tubule disruption and accompanying alterations in Ca2+ transients. The most likely explanation for this apparent discrepancy is the fact that this study was performed during the earliest phases of disease progression. It is known that hypertrophy is well developed and hypercontractile behavior occurs at about the initiation time point of this study (27), so the heart is still in a fully compensated state. It is not surprising that after 3 mo there are not enough myocytes with poor t-tubule organization to induce an overall decline in cardiac function detectable by echocardiographic imaging. Also, since our measurements were made only on the epicardial surface of the middle LV, we do not know the extent of t-tubule remodeling throughout other regions of the ventricle (endocardium, base vs. apex) during disease progression. Our work and that of others (35) have demonstrated that the number of affected cells increases with disease severity in general, but it is likely that the fact that we do not see any overt changes in cardiac function suggests that the number of affected cells is just too small to produce significant changes in myocardial mechanics. Our ongoing work in older animals (J. A. Wasserstrom, G. L. Aistrup, L. Beussink, and S. Shah, unpublished observations) suggests that the decline in myocardial function occurs with a delay related to a requirement for a critical number of affected cells rather than showing a sudden onset when enough cells are affected (a threshold effect). Later, as disease progresses farther, there is a closer correlation between t-tubule remodeling and disease progression in the form of growing systolic and diastolic dysfunction (35) (J. A. Wasserstrom, G. L. Aistrup, L. Beussink, and S. Shah, unpublished observations).

T-tubule remodeling and INa,L.

The mechanism(s) by which ranolazine decreased the percentage of myocytes with poor t-tubule organization (OI<0.8) is unclear. The fact that INa,L inhibition with ranolazine reduced t-tubule remodeling suggests that INa,L-mediated Na+ influx and the subsequent NCX-mediated Ca2+ accumulation are contributors to t-tubule disruption during disease progression in the SHR. An increase in the diastolic Ca2+ concentration may ultimately cause mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and apoptosis (8) and/or necrosis (18). Expression of cardiac sodium channels with the long-QT syndrome 3 mutation N1325S, which enhances INa,L, was associated with increased cardiomyocyte apoptosis and contractile dysfunction in mice (41). Ranolazine was reported to reduce cytosolic Ca2+, mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening, and cell death after global ischemia and reperfusion (which increase INa,L) in the guinea pig isolated heart (2). In sum, these findings and ours suggest that enhancers and inhibitors of INa,L may increase or reduce, respectively, injury and cell death associated with Ca2+ overload, including disruption of t-tubule organization. However, because ranolazine is reported to stabilize cardiac ryanodine receptors (20) and to inhibit the rapid delayed rectifier K+ current (IKr) (3), it is possible that other actions of the drug, in addition to inhibition of INa,L, may contribute to its beneficial effect in this study. However, since there is no IKr present in rat ventricle, it is unlikely that drug actions on this current could contribute to the effects of ranolazine described here.

We found that chronic INa,L block with ranolazine prevented the desynchronization of Ca2+ cycling along the cell length observed in CON myocytes. This effect would be expected if t-tubule organization was better preserved, because Ca2+ cycling properties should remain more synchronized and uniform when trigger Ca2+ can uniformly activate sarcoplasmic reticular Ca2+ release to enable rapid, synchronous, and efficient contraction. It is clear that t-tubule disruption occurs as part of the pathophysiology that is ultimately responsible for HF. Early intervention that prevents t-tubule disruption at the cellular level may slow or even reverse the progression from compensated, asymptomatic to decompensated HF.

INa,L block decreases rate sensitivity to Ca2+ alternans development.

We found that chronic INa,L inhibition had important effects on the rate vulnerability of Ca2+ alternans. This form of Ca2+ instability is probably responsible for APD alternans and the resulting T-wave alternans that are thought to be highly arrhythmogenic. APD alternans may underlie the repolarization gradients that are a substrate for reentrant arrhythmias (21, 25, 37). Thus the development of Ca2+ alternans at slow heart rates increases the vulnerability to reentry. We have demonstrated that there is a shift in Ca2+ alternans susceptibility to progressively slower heart rates during the progression of HF in the SHR model (11, 34). The underlying mechanism responsible for this increasing vulnerability to Ca2+ alternans is likely to be related to the slowing in the recovery of SR Ca2+ release as disease develops, making Ca2+ cycling unstable at increasing heart rates (11, 34). In this study we found that chronic INa,L inhibition prevented both the increase in Ca2+ alternans vulnerability to slow rates and the slowing in SR Ca2+ release restitution. This suggests 1) that INa,L in SHRs contributes to the slowing in Ca2+ restitution and resulting increased rate-dependent vulnerability to Ca2+ alternans and 2) that chronic block of INa,L in the SHR decreases vulnerability to Ca2+ alternans. These results demonstrate for the first time that chronic inhibition of INa,L not only prevents ultrastructural and hypertrophic remodeling but also reduces the substrate for reentrant arrhythmias that arise during development of HF. Inhibition of INa,L by ranolazine of electrical alternans may also contribute to its beneficial effects on cardiac function. Ranolazine reduces the transmural and beat-to-beat variability of action potential (AP) repolarization (3, 38). Effects of ranolazine to decrease inward INa,L and formation of early afterdepolarizations and to reduce the [Na+]i and NCX-mediated Ca2+ overloading may both be important to decrease the susceptibility of cardiac tissue to Ca2+ and electrical alternans. Again, it is interesting that ranolazine is effective in reducing alternans sensitivity in SHRs where IKr is absent and so cannot play a role in alternans formation, suggesting that the efficacy of the drug occurs through mechanisms that do not involve this current component.

Acute INa,L inhibition corrects Ca2 cycling defect.

We also found that acute block of INa,L improved both Ca2+ release and reuptake in CON myocytes with slow Ca2+ release. The fact that acute RAN treatment improved Ca2+ cycling properties in myocytes showing distinct defects in excitation-contraction coupling suggests that acute administration of this agent might also improve cellular and cardiac function in HF. Indeed, this may represent a unique cellular target and novel approach for pharmacotherapy in decompensated HF.

The Western blot results demonstrated that RAN did not alter expression levels of a number of key proteins involved in excitation-contraction coupling. Consequently, we conclude that the beneficial actions of RAN (5.4 μM) on HF development are likely to arise from its selective action to block INa,L. However, it is worth noting that it is also possible that RAN could indirectly reduce CaMKII activity (40), which could have important effects on Ca2+ cycling and could contribute to the beneficial effects of RAN treatment.

Clinical implications of chronic block of INa,L during HF development.

Our results demonstrate that it is possible to intervene during the transition from hypertension to decompensated HF in a manner that 1) slows the progression of both cellular and whole organ hypertrophy to decompensation, 2) significantly reduces t-tubule remodeling and the magnitude of Ca2+ cycling defects that contribute to both systolic and diastolic HF, and 3) reduces the vulnerability to Ca2+ alternans and its potential contributions to arrhythmias. A putative role for INa,L in HF development raises the possibility that any underlying pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for increased INa,L might not only contribute to disease development and the progression to HF but may also provide potential therapeutic targets for the prevention of HF.

GRANTS

This project was funded by a grant from Gilead Sciences (to J. A. Wasserstrom).

DISCLOSURES

N. El-Bizri, S. Rajamani, J. C. Shryock, and L. Belardinelli are employees of Gilead Sciences. Ranolazine (Ranexa) is owned by Gilead Sciences.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

G.L.A., D.K.G., J.E.K., N.S., J.N., S.R., J.C.S., L. Belardinelli, S.J.S., and J.A.W. conception and design of research; G.L.A., J.E.K., M.J.O., A.F.N., N.C., S.M., L. Beussink, N.S., N.E.-B., S.R., and J.A.W. performed experiments; G.L.A., J.E.K., M.J.O., A.F.N., N.C., S.M., L. Beussink, N.S., J.N., M.R., T.M., N.E.-B., S.R., S.J.S., and J.A.W. analyzed data; G.L.A., D.K.G., N.S., J.C.S., L. Belardinelli, S.J.S., and J.A.W. interpreted results of experiments; G.L.A. and J.A.W. drafted manuscript; G.L.A., S.R., J.C.S., L. Belardinelli, S.J.S., and J.A.W. edited and revised manuscript; G.L.A., D.K.G., J.E.K., M.J.O., A.F.N., N.C., S.M., L. Beussink, N.S., J.N., M.R., T.M., N.E.-B., S.R., J.C.S., L. Belardinelli, S.J.S., and J.A.W. approved final version of manuscript; M.J.O., N.E.-B., S.R., and J.A.W. prepared figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aistrup GL, Kelly JE, Kapur S, Kowalczyk M, Sysman-Wolpin I, Kadish AH, Wasserstrom JA. Pacing-induced heterogeneities in intracellular Ca2+ signaling, cardiac alternans, and ventricular arrhythmias in intact rat heart. Circ Res 99: e65–e73, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldakkak M, Camara AK, Heisner JS, Yang M, Stowe DF. Ranolazine reduced Ca2+ overload and oxidative stress and improved mitochondrial integrity to protect against ischemia reperfusion injury in isolated hearts. Pharmacol Res 64: 381–392, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L, Wu L, Fraser H, Zygmunt AC, Burashnikov A, Di Diego JM, Fish JM, Cordiero JM, Goodrow RJ, Jr, Scornik F, Perez G. Electrophysiologic properties and antiarrhythmic actions of a novel antianginal agent. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 9, Suppl 1: S65–S83, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balijepalli RC, Kamp TJ. Cardiomyocyte transverse tubule loss leads the way to heart failure. Future Cardiol 7: 39–42, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balijepalli RC, Lokuta AJ, Maertz NA, Buck JM, Haworth RA, Valdivia HH, Kamp TJ. Depletion of t-tubules and specific subcellular changes in sarcolemmal proteins in tachycardia-induced heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 59: 67–77, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C, Fraser H. Inhibition of late (sustained/persistent) sodium current: a potential drug target to reduce intracellular sodium-dependent calcium overload and its detrimental effects on cardiomyocyte function. Eur Heart J 6, Suppl 1: 13–17, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brette F, Orchard C. T-tubule function in mammalian cardiac myocytes. Circ Res 92: 1182–1192, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, Zhang X, Kubo H, Harris DM, Mills GD, Moyer J, Berretta R, Potts ST, Marsh JD, Houser SR. Ca2+ influx-induced sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ overload causes mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis in ventricular myocytes. Circ Res 97: 1009–1017, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Everett TH, Kok LC, Vaughn RH, Moorman R, Haines DE. Frequency domain algorithm for quantifying atrial fibrillation organization to increase defibrillation efficacy. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 48: 969–978, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ju YK, Saint DA, Gage PW. Hypoxia increases persistent sodium current in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol 497: 337–347, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapur S, Aistrup GL, Sharma R, Kelly JE, Arora R, Zheng J, Veramasuneni M, Kadish AH, Balke CW, Wasserstrom JA. Early development of intracellular calcium cycling defects in intact hearts of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H1843–H1853, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapur S, Wasserstrom JA, Kelly JE, Kadish AH, Aistrup GL. Acidosis and ischemia increase cellular Ca2+ transient alternans and repolarization alternans susceptibility in the intact rat heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H1491–H1512, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehnart SE, Wehrens XH, Laitinen PJ, Reiken SR, Deng SX, Cheng Z, Landry DW, Kontula K, Swan H, Marks AR. Sudden death in familial polymorphic ventricular tachycardia associated with calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) leak. Circulation 109: 3208–3214, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Louch WE, Mork HK, Sexton J, Stromme TA, Laake P, Sjaastad I, Sejersted OM. T-tubule disorganization and reduced synchrony of Ca2+ release in murine cardiomyocytes following myocardial infarction. J Physiol 574: 519–533, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyon AR, MacLeod KT, Zhang Y, Garcia E, Kanda GK, Lab MJ, Korchev YE, Harding SE, Gorelik J. Loss of t-tubules and other changes to surface topography in ventricular myocytes from failing human and rat heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 6854–6859, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maltsev VA, Reznikov V, Undrovinas NA, Sabbah HN, Undrovinas A. Modulation of late sodium current by Ca2+, calmodulin, and CaMKII in normal and failing dog cardiomyocytes: similarities and differences. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1597–H1608, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maltsev VA, Silverman N, Sabbah HN, Undrovinas AI. Chronic heart failure slows late sodium current in human and canine ventricular myocytes: implications for repolarization variability. Eur J Heart Fail 9: 219–227, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakayama H, Chen X, Baines CP, Klevitsky R, Zhang X, Zhang H, Jaleel N, Chua BH, Hewett TE, Robbins J, Houser SR, Molkentin JD. Ca2+- and mitochondrial-dependent cardiomyocyte necrosis as a primary mediator of heart failure. J Clin Invest 117: 2431–2444, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 355: 251–259, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parikh A, Mantravadi R, Kozhevnikov D, Roche MA, Ye Y, Owen LJ, Puglisi JL, Abramson JJ, Salama G. Ranolazine stabilizes cardiac ryanodine receptors: a novel mechanism for the suppression of early afterdepolarizations and torsade de pointes in long QT type 2. Heart Rhythm 9: 953–960, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pastore JM, Girouard SD, Laurita KR, Akar FG, Rosenbaum DS. Mechanism linking t-wave alternans to the genesis of cardiac fibrillation. Circulation 99: 1385–1394, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pieske B, Houser SR. [Na+]i handling in the failing human heart. Cardiovasc Res 57: 874–886, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pieske B, Maier LS, Piacentino V, 3rd, Weisser J, Hasenfuss G, Houser S. Rate dependence of [Na+]i and contractility in nonfailing and failing human myocardium. Circulation 106: 447–453, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pogwizd SM, Sipido KR, Verdonck F, Bers DM. Intracellular Na in animal models of hypertrophy and heart failure: contractile function and arrhythmogenesis. Cardiovasc Res 57: 887–896, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Restrepo JG, Karma A. Spatiotemporal intracellular calcium dynamics during cardiac alternans. Chaos 19: 037115, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shiferaw Y, Sato D, Karma A. Coupled dynamics of voltage and calcium in paced cardiac cells. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys 71: 021903, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shorofsky SR, Aggarwal R, Corretti M, Baffa JM, Strum JM, Al-Seikhan BA, Kobayashi YM, Jones LR, Wier WG, Balke CW. Cellular mechanisms of altered contractility in the hypertrophied heart: big hearts, big sparks. Circ Res 84: 424–434, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song LS, Sobie EA, McCulle S, Lederer WJ, Balke CW, Cheng H. Orphaned ryanodine receptors in the failing heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 4305–4310, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sossalla S, Maurer U, Schotola H, Hartmann N, Didie M, Zimmermann WH, Jacobshagen C, Wagner S, Maier LS. Diastolic dysfunction and arrhythmias caused by overexpression of CaMKII∂C can be reversed by inhibition of late Na+ current. Basic Res Cardiol 106: 263–272, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Undrovinas A, Maltsev VA. Late sodium current is a new therapeutic target to improve contractility and rhythm in failing heart. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem 6: 348–359, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verdonck F, Volders PG, Vos MA, Sipido KR. Intracellular Na+ and altered Na+ transport mechanisms in cardiac hypertrophy and failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 35: 5–25, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verdonck F, Volders PG, Vos MA, Sipido KR. Increased Na+ concentration and altered Na/K pump activity in hypertrophied canine ventricular cells. Cardiovasc Res 57: 1035–1043, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wasserstrom JA, Kapur S, Jones S, Faruque T, Sharma R, Kelly JE, Pappas A, Ho W, Kadish AH, Aistrup GL. Characteristics of intracellular Ca2+ cycling in intact rat heart: a comparison of sex differences. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H1895–H1904, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wasserstrom JA, Sharma R, Kapur S, Kelly JE, Kadish AH, Balke CW, Aistrup GL. Multiple defects in intracellular calcium cycling in whole failing rat heart. Circ Heart Fail 2: 223–232, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei S, Guo A, Chen B, Kutschke W, Xie YP, Zimmerman K, Weiss RM, Anderson ME, Cheng H, Song LS. T-tubule remodeling during transition from hypertrophy to heart failure. Circ Res 107: 520–531, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiss JN, Karma A, Shiferaw Y, Chen PS, Garfinkel A, Qu Z. From pulsus to pulseless: the saga of cardiac alternans. Circ Res 98: 1244–1253, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss JN, Nivala M, Garfinkel A, Qu Z. Alternans and arrhythmias: from cell to heart. Circ Res 108: 98–112, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu L, Rajamani S, Li H, January CT, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. Reduction of repolarization reserve unmasks the proarrhythmic role of endogenous late Na+ current in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1048–H1057, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu Y, Clusin WT. Calcium transient alternans in blood-perfused ischemic hearts: Observations with fluorescent indicator fura red. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 273: H2161–H2169, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yao L, Fan P, Jiang Z, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Wu Y, Kornyeyev D, Hirakawa R, Budas GR, Rajamani S, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. Nav1.5-dependent persistent Na+ influx activates CaMKII in rat ventricular myocytes and N1325S mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 301: C577–C586, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang T, Yong S, Drinko JK, Popovic ZB, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L, Wang QK. LQTS mutation N1325S in cardiac sodium channel gene SCN5A causes cardiomyocyte apoptosis, cardiac fibrosis and contractile dysfunction in mice. Int J Cardiol 147: 239–245, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]