Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the time-varying relationship of annual physical, psychiatric, and quality of life status with subsequent inpatient health care resource use and estimated costs.

Design

5-year longitudinal cohort study

Setting

13 ICUs at four teaching hospitals

Patients

138 patients surviving ≥2 years after ARDS

Interventions

None

Measurements and Main Results

Post-discharge inpatient resource use data (e.g., hospitalizations, skilled nursing, and rehabilitation facility stays) were collected via a retrospective structured interview at 2 years, with prospective collection every 4 months thereafter, until 5 years post-ARDS. Adjusted odds ratios for hospitalization and relative medians for estimated episode of care costs were calculated using marginal longitudinal two-part regression. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) number of inpatient admissions hospitalizations was 4 (2 – 8), with 114 (83%) patients reporting ≥1 hospital readmission. The median (IQR) estimated total inpatient post-discharge costs over 5 years were $58,500 ($19,700–$157,800, 90th percentile: $328,083). Better annual physical and quality of life status, but not psychiatric status, were associated with fewer subsequent hospitalizations and lower follow-up costs. For example, greater grip strength (per 6 kg) had an odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of 0.85 (0.73–1.00) for inpatient admission, with 23% lower relative median costs, 0.77 (0.69–0.87).

Conclusions

In a multi-site cohort of long-term ARDS survivors, better annual physical and quality of life status, but not psychiatric status, were associated with fewer hospitalizations and lower health care costs.

Keywords: Patient Readmission, Health Care Costs, Quality of Life, Intensive Care Unit, Critical Illness, Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Acute

INTRODUCTION

Survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) frequently experience physical, psychiatric and health-related quality of life (QOL) impairments.(1–5) Such impairments may impact long-term post-ARDS health care resource use and costs (6–10), particularly in light of healthcare systems more frequently adopting post-acute care, bundled payments or shared-savings programs.(11) Understanding the relationship of these post-discharge impairments, especially in long-term survivors after ARDS, with subsequent resource use and costs over longitudinal follow-up is important for health care policy and planning.(12) Prior research in Canada found that follow-up hospitalization costs were highest in the first year after ARDS, and lower in subsequent years.(1, 2) We hypothesized that follow-up hospitalizations and skilled nursing and rehabilitation facility stays, and associated costs, would decrease over the course of 5-year, longitudinal follow-up after ARDS.

Using a multi-site cohort of long-term ARDS survivors, our objective is to evaluate the relationship of time-varying, post-discharge measures of survivors’ physical status, psychiatric symptoms, and QOL with subsequent annual hospitalization, and associated episode of care costs, over 5 years after ARDS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Cohort

This analysis focused on long-term ARDS survivors, defined as those surviving ≥2 years after ARDS. Patients were recruited from the multi-site Improving Care of ALI Patients (ICAP) study that enrolled consecutive, mechanically ventilated patients with acute lung injury, determined by the American–European Consensus criteria (13) in effect during recruitment.(14) Consistent with the Berlin criteria (15), hereafter we use the term ARDS. Patients were enrolled from 13 ICUs at four teaching hospitals in Baltimore, Maryland from 2004 through 2007, with follow-up ending in late 2012. Exclusion criteria are reported in the supplemental digital content. We obtained informed consent after decision-making capacity was regained (or via proxy if patient incapacitated). The study site institutional review boards approved this research.

Outcome Measures: Follow-up Health Care Resource Use and Costs

Health care resource data were collected for 5 years following ARDS. These data were collected via a one-time, retrospective structured interview completed for long-term survivors at 2-year follow-up, and then continued prospectively every 4 months to complete 5-year follow-up. The data collection instrument, adapted from a previous ARDS study (1) and similar to another widely used instrument (16), collected data on follow-up inpatient care including: 1) hospitalizations, 2) skilled nursing facility stays, and 3) rehabilitation facility stays. Moreover, during years 3–5, outpatient data were collected. We verified health care resource data via systematic medical record review at the 3 non-federal study hospitals and at other facilities in the event of any patient/proxy uncertainty in self-report. We evaluated direct medical costs of health care resource use from the payer perspective. To evaluate the full economic burden associated with each follow-up hospitalization, we then calculated the “episode of care” cost that included costs of skilled nursing and rehabilitation facilities that were associated with follow-up hospitalizations.(17) (Additional detail provided in the supplemental digital content.)

Exposure Variables: Measures of Post-discharge Patient Status

Exposure variables were potential predictors of annual post-discharge hospitalizations and associated episode of care costs. We evaluated patient status using measures among three domains: physical status, psychiatric symptoms, and QOL. Physical status was evaluated via hand grip strength (in kilograms and percent predicted (18)), 6-minute walk distance (6MWD, in meters and percent predicted)(19), number of dependencies in activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental ADL (IADL) (20), and physical impairment (binary variable, defined as ≥2 IADL dependencies).(21) Psychiatric symptoms were evaluated via the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (continuous and binary [≥8] for anxiety and for depression symptoms)(22), and the Impact of Event Scale-Revised score (IES-R) (continuous and binary [≥1.6] scores for post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD] symptoms).(23) QOL was evaluated via the EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D) visual analogue scale (VAS) and utility score (24), and Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 (SF-36) physical and mental component scores (PCS and MCS, respectively ).(25) Continuous measures were scaled by their estimated minimum important difference (MID) (i.e., 6MWD, EQ-5D utility score, SF-36 PCS and MCS, and HADS) (26–29) or by one-half standard deviation (SD) when MID data was not available (e.g., hand grip strength, EQ-5D VAS, and IES-R score).(30)

Adjustment for Covariates: Baseline Patient and ICU-Related Exposures

To evaluate the independent associations of the primary exposures with the outcomes, we adjusted for the following patient baseline and ICU-related exposures, selected, a priori, per existing literature and our prior study results (15): gender, Charlson comorbidity index (31), ICU length of stay (LOS) during index hospitalization, and time-varying measures of informal caregiver status (i.e., informal caregiver residing with the patient and providing assistance) and health insurance status (i.e., Medicare or Medicaid, private insurance, or no insurance). Insurance data at 1-year follow-up was imputed using pre-ARDS insurance status, as 1-year data were not collected.

Statistical Methods

Variables were compared for patients with vs. without hospitalization over 5-year follow-up using chi-squared (or Fisher’s exact tests) and t-tests. Patients’ follow-up inpatient care cost data includes: 1) the presence or absence of an hospitalization in a given year; and 2) among those with any hospitalizations in a given year, a positive skew in episode of care cost distribution. Consequently, we evaluated predictors of cost using a marginal longitudinal two-part regression model (8, 32). First, a two-part “base model” was created including a main effect of time (continuous) and previously defined covariates. Second, to avoid overfitting, each of the 17 primary measures (e.g., measures of the physical, psychiatric, or QOL) was separately added to the “base model” to create 17 exposure models. The primary exposures were lagged so that the hospitalization and cost outcomes were evaluated with exposures reported from the prior year, e.g., exposures measured at the end of year 1 were evaluated with costs during year 2. Each of the 17 primary exposure models was extended to include an interaction of the primary exposure and time. (Additional detail provided in the supplemental digital content.) For each model, we performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding patients who died during years 3–5, evaluating whether survivorship status changed the results.

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC; NLMIXED procedure with 10 quadrature points), and R statistical software (version 2.15.2, Vienna, Austria). A 2-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Pre-ARDS and ICU-related Exposures

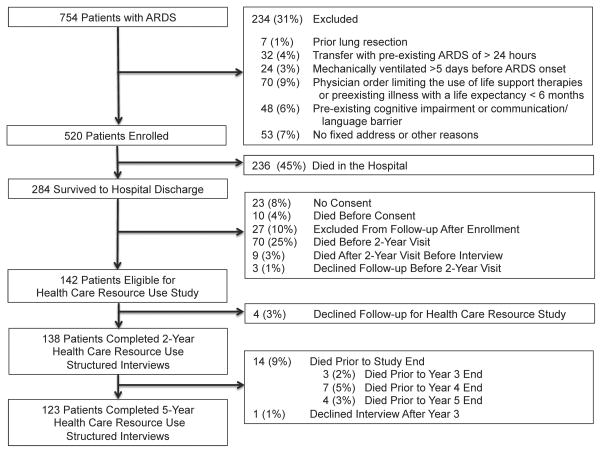

Of 142 two-year survivors, 138 (97%) completed the structured interview (Figure 1). From these two-year survivors, 124 patients survived to year 5, with 123/124 (99%) completing 5-year follow-up. In total, 114/138 (83%) 2-year survivors reported ≥1 hospitalization during 5-year follow-up. Comparing pre-ARDS characteristics with (n=114) vs. without (n=24) follow-up hospitalizations, patients with hospitalizations had a higher proportion with Medicare or Medicaid insurance, lower physical function, and higher ICU illness severity during the index ARDS hospitalization (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of 2-Year Survivors of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Followed For 5 Years; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 2-Year Survivors of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

| Patient and ICU-related Exposures | All Patients (n=138) |

Any Hospitalization over 5-YearFollow-up (n=114) |

No Hospitalization over 5-YearFollow-up (n=24) |

P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics/status prior to ARDS | ||||

| Age, Mean (SD) | 47 (14) | 47 (13) | 46 (16) | 0.770 |

| Female, No. (%) | 64 (46) | 51 (45) | 13 (54) | 0.400 |

| White, No. (%) | 78 (57) | 66 (58) | 12 (50) | 0.478 |

| Living at home, No. (%) | 131 (95) | 107 (94) | 24 (100) | 0.213 |

| Informal caregiver, No. (%) | 63 (46) | 51 (45) | 12 (50) | 0.638 |

| Estimated incomeb, $1,000, Mean (SD) | 52 (21) | 51 (21) | 53 (21) | 0.686 |

| Health insurancec, No. (%) | 129 (93) | 107 (94) | 22 (92) | 0.655 |

| Medicare or Medicaid | 88 (64) | 79 (69) | 9 (38) | 0.037 |

| Private insurance | 41 (30) | 28 (25) | 13 (54) | 0.004 |

| No insurance | 9 (7) | 7 (6) | 2 (8) | 0.655 |

| Baseline health status prior to ARDS | ||||

| Functional comorbidity index (47), Mean (SD) | 1.5 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.4) | 1.3 (1.0) | 0.346 |

| Physical Impairmentd, No. (%) | 50 (37) | 45 (40) | 5 (22) | 0.104 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, Mean (SD) | 1.9 (2.3) | 2.0 (2.4) | 1.1 (1.8) | 0.073 |

| Depression comorbidity, No. (%) | 31 (22) | 28 (25) | 3 (13) | 0.283 |

| Anxiety comorbidity, No. (%) | 10 (7) | 9 (8) | 1 (4) | 1.000 |

| EQ-5D VASe, Mean (SD) | 67 (28) | 67 (27) | 64 (33) | 0.604 |

| EQ-5D utility scoree, Mean (SD) | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.073 |

| SF-36 PCSe, Mean (SD) | 45 (12) | 43 (12) | 52 (10) | 0.003 |

| SF-36 MCSe, Mean (SD) | 45 (15) | 45 (15) | 47 (11) | 0.636 |

| ICU Status | ||||

| APACHE II score (48), Mean (SD) | 23 (8) | 24 (8) | 20 (6) | 0.031 |

| Mean Daily SOFA score (49), Mean (SD) | 5 (2) | 5 (2) | 5 (2) | 0.169 |

| ICU Length of Stay (days), Mean (SD) | 19 (18) | 19 (19) | 17 (11) | 0.508 |

ICU = intensive care unit, ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome, SD = standard deviation, No. = number, EQ-5D = EuroQol 5-dimension questionnaire, VAS = visual analogue scale, SF-36 = short form 36 questionnaire, PCS = physical component score, MCS = mental component score, APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, SOFA = sequential organ failure assessment

P-value calculated by chi-squared test (or Fisher’s exact test) and t-test.

Based on previously published method of income estimation based on zip code.(50)

Column percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding.

Physical impairment defined as ≥2 dependencies in instrumental activities of daily living.

Baseline values collected retrospectively to estimate status prior to hospital admission.

Inpatient Resource Use

Patients hospitalized during 5-year follow-up had a median (interquartile range [IQR]) of 4 (2–8) hospitalizations and a total LOS of 20 (9–54) days (Table 2). The most common follow-up admission category was infection (including pneumonia), accounting for 177/624 (28%) of hospitalizations. (Additional detail provided in the supplemental digital content in eTable 1.) The annual burden of patient-days spent in the hospital remained stable (Table 1 and eFigure 1). Based on data collected during years 3–5, 22% of hospitalizations included an ICU stay, with 40% of ICU stays requiring mechanical ventilation. During 5-year follow-up, 34 (25%) and 66 (48%) patients required a skilled nursing or rehabilitation facility stay, respectively, with these stays being most frequent during year 1 (22 [16%] and 48 [35%] patients, respectively) and decreasing to ≤8% of patients annually thereafter (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hospitalization, Skilled Nursing and Rehabilitation Facility Data During 5-Year Follow-up After Acute Respiratory Distress Syndromea

| Inpatient Facility | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Sizeb | (n=138) | (n=138) | (n=138) | (n=134) | (n=127) | (n=138) |

| Hospitalization | ||||||

| Patients Using Servicec, No. (%) | 72 (52) | 53 (38) | 52 (39) | 56 (44) | 45 (36) | 114 (83) |

| No. of Admissions, Median (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0 – 2.5) | 1.0 (1.0 – 2.0) | 2.0 (1.0 – 3.0) | 1.0 (1.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0 – 4.0) | 4.0 (2.0 – 8.0) |

| Length of Stayd, (d), Median (IQR) | 4 (2 – 7) | 4 (2 – 7) | 4 (3 – 7) | 4 (3–8) | 4 (3 – 8) | 20 (9 – 54) |

| Skilled Nursing Facility Stay | ||||||

| Patients Using Servicec, No. (%) | 22 (16) | 4 (3) | 5 (4) | 10 (8) | 6 (5) | 34 (25) |

| No. of Admissions, Median (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0 – 1.0) | 1.0 (1.0 – 1.3) | 1.0 (1.0 – 1.0) | 1.0 (1.0 – 3.0) | 2.0 (1.0 – 4.0) | 1.0 (1.0 – 2.0) |

| Length of Stayd, (d), Median (IQR) | 58 (13 – 104) | 90 (60 – 97) | 30 (120 – 164) | 57 (32 – 89) | 47 (31 – 140) | 60 (30 – 201) |

| Rehabilitation Facility Stay | ||||||

| Patients Using Servicec, No. (%) | 48 (35) | 11 (8) | 6 (4) | 9 (7) | 7 (6) | 66 (48) |

| No. of Admissions, Median (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0 – 1.0) | 1.0 (1.0 – 1.0) | 1.0 (1.0 – 1.0) | 1.0 (1.0 – 1.0) | 2.0 (1.0 – 2.0) | 1.0 (1.0 – 2.0) |

| Length of Stayd, (d), Median (IQR) | 21 (10 – 30) | 30 (21 – 60) | 32 (29 – 86) | 21 (7 – 71) | 26 (18 – 32) | 28 (14 – 60) |

| Summary Cost | ||||||

| Patients Using Servicec, No. (%) | 98 (71) | 54 (39) | 55 (40) | 58 (43) | 57 (45) | 124 (90) |

| No. of Admissions, Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0 – 3.0) | 1.0 (1.0 – 3.0) | 2.0 (1.0 – 4.0) | 1.0 (1.0 – 4.0) | 2.0 (1.0 – 5.0) | 4.0 (2.0 – 9.0) |

| Length of Stayd, (d), Median (IQR) | 23 (7 – 59) | 8 (4 – 17) | 11 (6 – 27) | 10 (3 – 38) | 11 (5 – 35) | 42 (16 – 120) |

No. = number, IQR = inter-quartile range, d = days, k = thousand

Additional detail on estimated cost results is provided in the supplemental digital content in eTable 2.

Sample size indicates number of patients eligible for follow-up for each time period (i.e. patients alive and consenting, and not lost to follow-up).

Percentages calculated by number of patients utilizing service divided by sample size in each follow-up year.

Reported admissions with missing length of stay data (36 of 811 (4.4%) admissions) had length of stay imputed using the cohort median stay for each admission type (hospital, skilled nursing, or rehabilitation) and admission category (for hospital admissions only). Medians calculated are the median number of days per admission within each year. The total length of stay represents the median total number of days over the entire 5-year follow-up period.

Estimated Costs of Inpatient Care

Hospitalization costs accounted for the majority (83%) of follow-up inpatient costs, with a median estimated hospitalization cost during 5-year follow-up of $57,500 (IQR: $25,500–$150,100; 90th percentile: $278,400), while total inpatient follow-up (including hospitalizations, skilled nursing facility stays, and rehabilitation facility stays) costs were $58,500 ($19,700–$157,800, 90th percentile: $328,083). Throughout follow-up, annual median inpatient costs remained stable.(Additional data in eTable 2).

Primary Exposures’ Associations with Follow-up Hospitalizations

Adjusting for baseline patient and ICU-related exposures and follow-up time, greater strength, physical functioning, and higher QOL measures at annual assessments were significantly associated with lower odds of hospitalization during the subsequent year (Table 3), with odds ratios (95% confidence interval [CI]) for hand grip strength of 0.86 (0.77–0.97, p=0.013) per increase of 12% predicted, for 6-minute walk test of 0.94 (0.88–0.99, p=0.025) per increase of 5% predicted, for EQ-5D utility score of 0.92 (0.87–0.98, p=0.008) per increase of 0.07 points, and for SF-36 PCS of 0.85 (0.78–0.94, p=0.001) per increase of 5 points. There were no significant associations of 6 measures of psychiatric symptoms with hospitalization (Table 3).

Table 3.

Post-Discharge Exposures Associated with Follow-up Hospitalization and Episode of Care Costs After Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

| Post-Discharge Exposurea | Any Hospitalization | Episode of Care Cost | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Valueb | Relative median (95% CI) | P Valuec | |

| Physical assessment | ||||

| Grip strengthd, per 6 kg | 0.85 (0.73, 1.00) | 0.047 | 0.77 (0.69, 0.87) | <0.001 |

| Grip strength % predictedd, per 12% | 0.86 (0.77, 0.97) | 0.013 | 0.89 (0.81, 0.97) | 0.006 |

| 6 minute walk distancee, per 30m | 0.94 (0.89, 1.00) | 0.045 | 0.93 (0.89, 0.97) | 0.001 |

| 6 minute walk % predictede, per 5% | 0.94 (0.88, 0.99) | 0.025 | 0.93 (0.89, 0.97) | <0.001 |

| ADL number of dependencies | 0.97 (0.95, 1.12) | 0.717 | 1.07 (0.96, 1.21) | 0.217 |

| IADL number of dependencies | 1.05 (0.96, 1.14) | 0.268 | 1.08 (1.02, 1.16) | 0.012 |

| Physical impairmentf | 1.30 (0.89, 1.90) | 0.174 | 1.19 (0.87, 1.63) | 0.270 |

| Psychiatric symptoms | ||||

| Depressiong | 1.22 (0.82, 1.82) | 0.331 | 0.90 (0.65, 1.25) | 0.532 |

| HADS depression subscalef, per 1.5 | 1.04 (0.96, 1.12) | 0.314 | 1.05 (0.98, 1.11) | 0.170 |

| Anxietyg | 0.98 (0.67, 1.45) | 0.937 | 0.95 (0.68, 1.31) | 0.746 |

| HADS anxiety subscalef, per 1.5 | 1.00 (0.93, 1.08) | 0.952 | 1.03 (0.97, 1.10) | 0.284 |

| PTSDd,h | 1.27 (0.77, 2.11) | 0.348 | 1.17 (0.80, 1.70) | 0.412 |

| IES-R scored per 0. 4 | 1.03 (0.93, 1.14) | 0.587 | 1.02 (0.95, 1.11) | 0.553 |

| Health-Related Quality of life | ||||

| EQ-5D VASd, per 10 | 0.94 (0.86, 1.03) | 0.166 | 0.97 (0.91, 1.04) | 0.442 |

| EQ-5D utility scoree, per 0.07 | 0.92 (0.87, 0.98) | 0.008 | 0.95 (0.90, 0.99) | 0.013 |

| SF-36 PCSe, per 5 | 0.85 (0.78, 0.94) | 0.001 | 0.92 (0.86, 0.98) | 0.016 |

| SF-36 MCSe, per 5 | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) | 0.792 | 0.99 (0.94, 1.05) | 0.820 |

CI = confidence interval, kg = kilogram, m = meter, ADL = activities of daily living, IADL = instrumental activities of daily living, HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder, IES-R = impact of event scale-revised, EQ-5D = EuroQol 5-dimension questionnaire, VAS = visual analogue scale, SF-36 = short form 36 questionnaire, PCS = physical component score, MCS = mental component score.

For each of the logistic and linear models, each post-discharge exposure was added separately to the same base model that adjusted for sex, informal caregiver status, insurance status, Charlson comorbidity index, intensive care unit length of stay, and time (i.e. year of follow-up).

P values were calculated using multivariable logistic regression analysis of patients with any versus no hospitalization during each follow-up year. Hosmer-Lemeshow test confirmed model fit.

P values were calculated using multivariable linear regression analysis of log-transformed yearly episode of care costs associated with each hospitalization, including the costs of skilled nursing and rehabilitation facility costs which were associated with hospitalizations. (17)

Grip strength, IES-R score, and EQ-5D-VAS are all scaled by one-half of the standard deviation (30) within this study cohort.

6MWD, HADS, EQ-5D-utility score, SF-36 PCS and MCS, and were scaled by the reported minimally important difference (26–29).

Physical impairment was defined by ≥2 dependencies in independent activities of daily living.

Anxiety and depression symptoms defined by HADS scores ≥8.

PTSD defined by IES-R score ≥1.6.

Similar findings were observed for post-discharge factors and estimated median episode of care costs (Table 3), with estimated relative median costs being 23% lower per 6kg increase in grip strength (relative median 0.77, 95% CI: 0.69–0.87, p<0.001), 7% lower per 5% increase in 6 minute walk percent predicted (0.93, 0.89–0.97, p<0.001), 5% lower per 0.07 point increase in EQ-5D utility score (0.95, 0.90–0.99), p=0.013), and 8% lower per 5 point increase in SF-36 PCS (0.92, 0.86–0.98), p=0.016), after adjusting for the baseline patient and ICU-related exposures and time.

Sensitivity analysis revealed no material change in results excluding patients who died during years 3–5. There were statistically significant interaction terms in the regression models for the following five exposure variables: 6MWD (p < 0.001 for interaction term with time), grip strength (p = 0.006), IADL dependencies (p= 0.017), EQ-5D (p = 0.014) and SF-36 PCS (p < 0.001). For all five exposure variables, extended regression models including an interaction term demonstrated that associations of the exposure variable with annual inpatient costs increased over time. For example, in the second versus fifth year, the relative median costs were 4% versus 13% lower per 30-meter increase in 6MWD. For the outcome of any vs. no hospitalization, only the SF-36 PCS had a significant interaction with time (p= 0.003), also demonstrating a stronger relationship over time.

Outpatient Resource Use and Cost

In regards to outpatient resource use during years 3–5, 127/138 (92%) of two-year survivors visited a primary care physician. Specialist physicians were visited by 119/138 (86%) of patients. Psychiatry was the most commonly visited, with an annual average of 18% (25/138) patients. Considering mental health providers more broadly (e.g., psychiatrist, psychologist or counselor), an annual average of 40% (55/138) saw a mental health provider (Table 4 and supplemental digital content). In a sub-analysis of post-discharge psychiatric symptoms exposures and outpatient mental health visits and costs, we found that depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms were all significantly associated with an increased odds of any outpatient mental health visit in the subsequent follow-up year, but only anxiety had a significant association with increased outpatient mental health costs (eTable 3 and eTable 4.)

Table 4.

Outpatient Visits During Follow-up Years 3, 4, and 5a

| Outpatient Service | Annual Frequency |

|---|---|

| Physician Visits | |

| Primary Care | |

| Patients Using, No. (%) | 108 (78) |

| No. Visits, Median (IQR) | 4 (2 – 6) |

| Specialist | |

| Patients Using, No. (%) | 98 (71) |

| No. Visits, Median (IQR) | 7 (3 – 13) |

| Most Common Specialty Typesb, No. (%) | |

| Psychiatrist | 25 (18) |

| Ophthalmologist | 24 (17) |

| Cardiologist | 21 (15) |

| Pulmonologist | 18 (13) |

| Infectious disease | 18 (13) |

| Gynecologist | 15 (11) |

| Orthopedic Surgeon | 15 (11) |

| Nephrologist | 14 (10) |

| Neurologist | 13 (10) |

| Psychologist | |

| Patients Using, No. (%) | 12 (9) |

| No. Visits, Median (IQR) | 5 (2 – 12) |

| Counselor | |

| Patients Using, No. (%) | 32 (23) |

| No. Visits, Median (IQR) | 10 (3 – 16) |

| Psychiatrist, Psychologist or Counselor | |

| Patients Using, No. (%) | 55 (40) |

| No. Visits, Median (IQR) | 10 (3 – 20) |

| Physical therapistc | |

| Patients Using, No. (%) | 16 (12) |

| No. Visits, Median (IQR) | 8 (4 – 19) |

| Occupational therapistc | |

| Patients Using, No. (%) | 4 (3) |

| No. Visits, Median (IQR) | 3 (2 – 6) |

| Social worker | |

| Patients Using, No. (%) | 28 (20) |

| No. Visits, Median (IQR) | 4 (2 – 10) |

| Home oxygen: Patients Using, No. (%) | 14 (10) |

| Outpatient medication | |

| Patients Using Any Medication, No. (%) | 114 (83) |

| No. of different medications taken daily, Median (IQR) | 5 (3 – 8) |

| Patients Using Psychiatric Medication, No. (%) | 59 (43) |

No. = number, IQR = interquartile range

Data collected during post-ARDS follow-up years 3, 4 and 5 years, with the average number (percentage) of patients using each outpatient service annually and the median (IQR) annual number of visits calculated for this 3-year period reported here. (Additional detail on outpatient visits by year is provided in the supplemental digital content in eTable 4.)

These categories are not mutually exclusive as patients may have visited multiple types of subspecialty providers.

Rehabilitation services (when combining inpatient and outpatient physical or occupational therapy) were used by 84/138 (61%) of patients, with the annual percentage of patients increasing over time (years 3, 4 and 5: 23 [17%], 35 [26%], and 41 [35%] respectively).

DISCUSSION

In this multisite, longitudinal, cohort study of long-term ARDS survivors, 83% had ≥1 hospitalization with a median (IQR) of 4 (2–8) over 5-year follow-up, with annual median costs remaining stable, without decrease. Throughout follow-up, greater muscle strength, physical functioning and related QOL scores, but not psychiatric symptoms, were consistently associated with fewer subsequent hospitalizations and lower associated health care costs.

This study is novel since prior studies have not evaluated the association of ARDS survivors’ time-varying post-discharge status with their subsequent hospitalizations and associated costs.(6, 9) Hence, there can be limited comparison to prior literature. Compared to a Canadian ARDS study (1, 2), ours found higher mean annual costs, with inpatient costs >2-fold greater during the first year (i.e. $22,200 vs. $10,000 per patient). Moreover, costs decreased to $2,300 by year 5 in the Canadian study, while costs in our study remained stable, making our study costs 10-fold greater by year 5. Lower costs in the Canadian study are possibly due to fewer reported hospitalizations (8), differences in patients’ pre-ARDS comorbidities and socioeconomic status, and differences in healthcare systems. A Canadian population-based study reported that ICU survivors had higher health care resource use, including more frequent hospitalization, compared to a control group of hospitalized non-critically ill patients.(10)

Among time-varying physical exposure variables, improved performance-based measures of strength and physical functioning, such as hand grip strength and 6MWD, had a significant association with decreased odds of future hospitalizations and associated costs, whereas self-reported physical functioning measures (ADL and IADL) were not consistently associated. However, other self-reported measures (e.g., EQ-5D utility score and SF-36 PCS QOL instruments) were significantly associated with hospitalization and costs. These findings may have several explanations, including measurement differences (objective performance-based vs. subjective self-reported measure), instrument scaling (e.g., ceiling/floor effect), and environmental effects incorporated in ADL and IADL measures, possibly modifying associations with resource use.(3) Several post-discharge exposures had a significant interaction with time, with the relationship strengthening over time. While these interactions might be influenced by a survivor bias, a sensitivity analysis excluding patients who died during follow-up years 3–5 found no material changes.

Although psychiatry was the most frequently visited outpatient specialty, only 39/624 (6%) hospitalizations had a psychiatric admission category. In addition, neither the SF-36 MCS nor any psychiatric measures (e.g., anxiety, depression and PTSD symptoms) had significant associations with follow-up resource use. This is consistent with a medical-surgical ICU survivor study (33), which found no association of 3-month post-discharge psychiatric symptoms and subsequent hospitalizations during 3–12 month follow-up. During years 3–5 the proportion of patients visiting a psychiatrist remained stable (16–21%), as did the proportion taking psychiatric medications (33–36%) (eTable 4). In a population-based cohort study in Denmark (34), ICU survivors had a cumulative incidence of psychiatric medication prescriptions of 19% that increased steadily over 1-year follow-up.

Studies evaluating readmissions following pneumonia and sepsis have commonly evaluated short-term 30- or 90-day readmission.(35, 36) Such studies reported, for example, that short-term readmissions are more frequent in a post-sepsis population compared to non-sepsis patients.(36, 37) A study on sepsis survivors (38), reported year 1 costs were 3-fold higher than years 2 and 3, contrasting with our finding that hospitalization costs remained fairly constant throughout follow-up.

While there is evidence that rehabilitation can decrease resource use in other populations, e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (39), it remains unclear whether post-ICU interventions may decrease follow-up hospitalizations in ICU survivors. For example, although rehabilitation implemented early in the ICU may reduce resource use (40–42), rehabilitation and other interventions after ICU discharge have not demonstrated the same benefit.(43–45) Further research is needed, focusing on interventions targeting muscle strength and physical functioning, based on the findings of this analysis.

Our study has potential limitations. First, we have no pre-ARDS comparison data for resource use and cannot determine if reported post-ARDS resource use is higher, directly attributable to the ARDS episode, or driven by other factors. Second, given the observational design, we cannot elucidate cause and effect relationships between the exposures and outcomes. Third, although the sample size is relatively large for a prospective longitudinal study, we may be underpowered to detect some exposure-outcome associations. Fourth, the health care resource use data for the first two years was collected by patient report of those patients surviving at least 2 years, therefore, the patient cohort evaluated long-term ARDS survivors without data on resource use of patients dying within 2 years post-ARDS. However, no difference in resource use predictors was found when patients dying during follow-up were excluded in a prior study (1) or in our sensitivity analysis excluding patients dying in years 3–5. In addition, given that data collected over the first 2 years was done via a one-time structured interview, recall bias may led to underestimated resource use, particularly in these first 2 years, that we attempted to address via performing systematic medical record verification. Fifth, costs may not be generalizable to other geographic areas as patients were enrolled from urban teaching hospitals in a single U.S. city and Maryland has a regulated all-payer payment system.(46) Therefore, evaluating patterns of health care resource use, rather than costs, may be more consistent for comparison. Sixth, we only have outpatient resource use data for years 3–5, limiting evaluation of these data. Finally, individual patient-level costs were not available for all post-discharge data; therefore, costs were estimated using established methods. It is possible that costs were underestimated because they are derived from pooled All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRG) data, possibly diminishing the influence of extreme costs.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this longitudinal, 5-year follow-up study demonstrated that the vast majority of inpatient resource use for long-term survivors of ARDS are due to hospitalizations, with 83% of patients having ≥1 follow-up hospitalization and half of patients having at least 4 hospitalizations during follow-up. Throughout 5-year follow-up, greater muscle strength, physical functioning and quality of life were consistently associated with fewer subsequent hospitalizations and lower associated costs. In ARDS survivors, the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving strength and physical functioning should be further evaluated for their effect on reducing health care resource use and costs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Margaret Herridge, MD, MPH for input regarding data collection methods for health care resource use and review of the draft manuscript, Lori Fisher, MD for research on outpatient costing, and Lin Chen, BS and Christopher Mayhew, BS for assistance with data management.

Footnotes

- Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

- Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

- Final approval of the version to be published; AND

- Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: All 12 authors have disclosed that they do not have any conflicts of interest. Supported by the National Institutes of Health (P050HL73994, R01HL088045, and K24HL088551). D.M.N. received support from a Clinician-Scientist Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health.

Copyright form disclosures: Dr. Lord disclosed other support (He is the CEO of a startup that works in Health IT Cybersecurity, and as a result, has many relationships, paid and unpaid, in Health IT broadly. However, none of them relates to this work). Dr. Dinglas received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Mendez-Tellez received support for article research from the NIH. Dr. Shanholtz received support for article research from the NIH. His institution received funding from the NIH-NHLBI. Dr. Pronovost received funding from Johns Hopkins University (Employer), Lehigh Speakers Bureau, and Penguin Publishing-Book Royalties. Dr. Needham received support for article research from the NIH. His institution received funding from the NIH, AHRQ, and Australian NHMRC. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Tomlinson G, et al. Two-year outcomes, health care use, and costs of survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(5):538–544. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200505-693OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(14):1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwashyna TJ, Netzer G. The burdens of survivorship: an approach to thinking about long-term outcomes after critical illness. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine. 2012;33(4):327–338. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1321982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desai SV, Law TJ, Needham DM. Long-term complications of critical care. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(2):371–379. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fd66e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):502–509. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lone NI, Seretny M, Wild SH, et al. Surviving intensive care: a systematic review of healthcare resource use after hospital discharge*. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(8):1832–1843. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a409c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coopersmith CM, Wunsch H, Fink MP, et al. A comparison of critical care research funding and the financial burden of critical illness in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(4):1072–1079. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823c8d03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruhl AP, Lord RK, Panek JA, et al. Health care resource use and costs of two-year survivors of acute lung injury. An observational cohort study. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2015;12(3):392–401. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201409-422OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lone NI, Gillies MA, Haddow C, et al. Five Year Mortality and Hospital Costs Associated With Surviving Intensive Care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201511-2234OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill AD, Fowler RA, Pinto R, et al. Long-term outcomes and healthcare utilization following critical illness - a population-based study. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1248-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mechanic R. Post-acute care--the next frontier for controlling Medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):692–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unroe M, Kahn JM, Carson SS, et al. One-year trajectories of care and resource utilization for recipients of prolonged mechanical ventilation: a cohort study. Annals of internal medicine. 2010;153(3):167–175. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, et al. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149(3 Pt 1):818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Needham DM, Dennison CR, Dowdy DW, et al. Study protocol: The Improving Care of Acute Lung Injury Patients (ICAP) study. Crit Care. 2006;10(1):R9. doi: 10.1186/cc3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Force ADT, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sirey JA, Meyers BS, Teresi JA, et al. The Cornell Service Index as a measure of health service use. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(12):1564–1569. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.12.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cutler DM, Ghosh K. The potential for cost savings through bundled episode payments. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1075–1077. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1113361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathiowetz V, Kashman N, Volland G, et al. Grip and pinch strength: normative data for adults. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1985;66(2):69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balke B. Rep 63–6. Civil Aeromedical Research Institute; 1963. A Simple Field Test for the Assessment of Physical Fitness; pp. 1–8. Report. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of Illness in the Aged. The Index of Adl: A Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. Depressive symptoms and impaired physical function after acute lung injury: a 2-year longitudinal study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(5):517–524. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0503OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bienvenu OJ, Williams JB, Yang A, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of acute lung injury: evaluating the Impact of Event Scale-Revised. Chest. 2013;144(1):24–31. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Group TE. EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ware JE, Jr, Bjorner JB, Kosinski M. Practical implications of item response theory and computerized adaptive testing: a brief summary of ongoing studies of widely used headache impact scales. Medical care. 2000;38(9 Suppl):II73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walters SJ, Brazier JE. What is the relationship between the minimally important difference and health state utility values? The case of the SF-6D. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2003;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan KS, Pfoh ER, Denehy L, et al. Construct validity and minimal important difference of 6-minute walk distance in survivors of acute respiratory failure. Chest. 2015;147(5):1316–1326. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samsa G, Edelman D, Rothman ML, et al. Determining clinically important differences in health status measures: a general approach with illustration to the Health Utilities Index Mark II. PharmacoEconomics. 1999;15(2):141–155. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199915020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puhan MA, Frey M, Buchi S, et al. The minimal important difference of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2008;6:46. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Medical care. 2003;41(5):582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diehr P, Yanez D, Ash A, et al. Methods for analyzing health care utilization and costs. Annual review of public health. 1999;20:125–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.20.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davydow DS, Hough CL, Zatzick D, et al. Psychiatric symptoms and acute care service utilization over the course of the year following medical-surgical ICU admission: a longitudinal investigation*. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(12):2473–2481. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wunsch H, Christiansen CF, Johansen MB, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses and psychoactive medication use among nonsurgical critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation. JAMA. 2014;311(11):1133–1142. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prescott HC, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ. Readmission diagnoses after hospitalization for severe sepsis and other acute medical conditions. JAMA. 2015;313(10):1055–1057. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones TK, Fuchs BD, Small DS, et al. Post-Acute Care Use and Hospital Readmission after Sepsis. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2015;12(6):904–913. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201411-504OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prescott HC, Langa KM, Liu V, et al. Increased 1-year healthcare use in survivors of severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(1):62–69. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0471OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee H, Doig CJ, Ghali WA, et al. Detailed cost analysis of care for survivors of severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(4):981–985. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000120053.98734.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubi M, Renom F, Ramis F, et al. Effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation in reducing health resources use in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2010;91(3):364–368. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lord RK, Mayhew CR, Korupolu R, et al. ICU early physical rehabilitation programs: financial modeling of cost savings. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(3):717–724. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182711de2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kayambu G, Boots R, Paratz J. Physical therapy for the critically ill in the ICU: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(6):1543–1554. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827ca637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morris PE, Griffin L, Berry M, et al. Receiving early mobility during an intensive care unit admission is a predictor of improved outcomes in acute respiratory failure. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2011;341(5):373–377. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31820ab4f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walsh TS, Salisbury LG, Merriweather JL, et al. Increased Hospital-Based Physical Rehabilitation and Information Provision After Intensive Care Unit Discharge: The RECOVER Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA internal medicine. 2015;175(6):901–910. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cuthbertson BH, Rattray J, Campbell MK, et al. The PRaCTICaL study of nurse led, intensive care follow-up programmes for improving long term outcomes from critical illness: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b3723. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mehlhorn J, Freytag A, Schmidt K, et al. Rehabilitation interventions for postintensive care syndrome: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(5):1263–1271. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rajkumar R, Patel A, Murphy K, et al. Maryland’s All-Payer Approach to Delivery-System Reform. N Engl J Med. 2014 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1314868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Groll DL, To T, Bombardier C, et al. The development of a comorbidity index with physical function as the outcome. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2005;58(6):595–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(7):707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muni S, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, et al. The influence of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status on end-of-life care in the ICU. Chest. 2011;139(5):1025–1033. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.