Abstract

Performance trends in elite butterfly swimmers are well known, but less information is available regarding master butterfly swimmers. We investigated trends in participation, performance and sex differences in 9,606 female and 13,250 male butterfly race times classified into five-year master groups, from 25-29 to 90-94 years, competing in the FINA World Masters Championships between 1986 and 2014. Trends in participation were analyzed using linear regression analysis. Trends in performance changes were investigated using mixed-effects regression analyses with sex, distance and a calendar year as fixed variables. We also considered interaction effects between sex and distance. Participation increased in master swimmers older than ~30-40 years. The men-to-women ratio remained unchanged across calendar years and master groups, but was lower in 200 m compared to 50 m and 100 m. Men were faster than women from 25-29 to 85-89 years (p < 0.05), although not for 90-94 years. Sex and distance showed a significant interaction in all master groups from 25-29 to 90-94 years for 200m (p < 0.05). For 50 m and 100 m, a significant sex × distance interaction was observed from 25-29 to 75-79 years (p < 0.05), but not in the older groups. In 50 m, women reduced the sex difference in master groups 30-34 to 60-64 years (p < 0.05). In 100 m, women decreased the gap to men in master groups 35-39 to 55-59 years (p < 0.05). In 200 m, the sex difference was reduced in master groups 30-34 to 40-44 years (p < 0.05). In summary, women and men improved performance at all distances, women were not slower compared to men in the master group 90-94 years; moreover, women reduced the gap to men between ~30 and ~60 years, although not in younger or older master groups.

Key words: aging, master athletes, sex difference, swimming

1. Introduction

Swimming as open-water swimming has a very long tradition (Eichenberger et al., 2012; Knechtle et al., 2014, 2015; Vogt et al., 2013). Competitive pool swimming is one of the most popular Olympic sports practiced by millions of athletes worldwide. Research in competitive swimming has concentrated mostly on physiological and biomechanical aspects and less on performance analysis (Costa et al., 2012). In addition to the competitions for elite athletes, older swimmers participate in age-specific categories for master athletes (Knechtle et al., 2016). Master swimmers are defined by the FINA (Fédération Internationale de Natation) as athletes equal or older than 25 years (www.fina.org). Swimming competitions are held in freestyle, backstroke, breaststroke and butterfly strokes and in the combination of the four strokes as the individual medley (www.fina.org). Considering scientific research, freestyle swimming seems to be more attractive than other strokes such as butterfly. For instance, to date, a total of 167 scientific papers have been published on freestyle swimming performance, whereas only 41 papers on butterfly swimming performance according to the Pubmed database (the search of Pubmed database - www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Pubmed - was performed on June 3, 2016 using the keywords ‘freestyle, swimming, performance’ and ‘butterfly, swimming, performance’ in the title).

In athletic performance, each distance and/or discipline has its age of optimum performance (Allen and Hopkins, 2015). In competitive pool swimming, the age of fastest swimmers competing in the World Championships and Olympic Games increased in the last 20 years and was higher in men compared to women (König et al., 2014). For elite butterfly swimmers, the age of peak performance (Zingg et al., 2014) and the sex difference in peak butterfly performance (König et al., 2014; Wolfrum et al., 2013; Zingg et al., 2014) have been already investigated. Most of research on this sport discipline concerns elite swimmers and less information is available regarding master swimmers. Considering master athletes, it is known that swimming performance decreases with age (Gatta et al., 2006; Senefeld et al., 2016). The decrease in performance in master swimmers is due to both a decrease in the metabolic power available and an increase in the energy cost of swimming (Zamparo et al., 2012). Among the four competitive strokes, a decrease in swimming speed was found highest in butterfly, where slowing with age was unaffected by the length of the race (Hartley and Hartley, 1986). However, little data exists for changes in performance across years for master swimmers (Senefeld et al., 2016).

Apart from the World Championships for elite swimmers, since 1986 the FINA holds biannually World Masters Championships (http://www.fina.org/discipline/masters) for all disciplines and distances in pool and open-water swimming. Butterfly swimming is one of the four major swimming strokes where the other three are freestyle, backstroke and breaststroke. A recent study investigating 65,584 freestyle master swimmers from 25-29 to 85-89 years competing in the FINA World Masters Championships between 1986 and 2014 showed that participation increased in both sexes mainly in older age groups, both sexes improved across time performance in all distances, and women were not slower than men in age groups 80-84 to 85-89 years (Knechtle et al., 2016).

Trends in performance and sex difference in performance in master butterfly swimmers are, however, not known. The knowledge of participation and performance trends of this specific cohort of swimmers would enable both athletes and coaches to enhance training and competing in this specific stroke. The aim of the present study was, therefore, to investigate changes in participation and performance in butterfly master swimmers competing in the FINA World Masters Championships between 1986 and 2014 in distances from 50 to 200 m. We hypothesized that participation would increase and performance would improve as it had been shown for master marathoners (Ahmadyar et al., 2015; Lepers and Cattagni, 2012) and master freestyle swimmers (Knechtle et al., 2016). Based on recent findings for master freestyle swimmers, we also expected to find differences between sexes regarding participation and performance.

Material and Methods

Ethics

The Institutional Review Board of St. Gallen, Switzerland, approved this study. Since the research involved analysis of publicly available data, the requirement for informed consent was waved.

Data sampling and analysis

All data were obtained from the official and publicly accessible FINA website (www.fina.org). All female and male athletes competing in all master groups in the FINA World Masters Championships in butterfly for all distances (i.e. 50 m, 100 m, and 200 m) between 1986 and 2014 were analyzed for trends in participation, performance and sex differences. To eliminate a selection bias (i.e. restriction to a limited number of top swimmers), all successful female and male swimmers for all master groups in all years were included in data analysis. No swimmer was excluded. Mean performance time (min:s) for all master groups for each year was calculated.

Statistical analysis

Trends in participation were examined using single linear regression analysis. The percent increase in participation was calculated using the equation which considered the number of participants in 2014 minus the number of participants in 1986 divided by the number of participants in 1986. The men-to-women ratio was calculated with all men and all women for each master group and the trend across years and across master groups was examined using single linear regression analysis. Multiple groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparison test. A mixed-effects regression model with the finisher as a random variable to consider finishers who completed several races was used to investigate changes in performance. We included sex, race distance and a calendar year as fixed variables. Interaction effects between sex and race distance were considered and the final model was selected by means of the Akaike information Criterion (AIC). Sex difference in swimming performance was calculated using the following equation: ([race time in women] – [race time in men] / [race time in men] × 100). Trends in sex difference in swimming performance were examined using single linear regression analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 22, IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Significance was accepted at p < 0.05 (two-sided for t-tests). Data in the text and tables are given as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Results

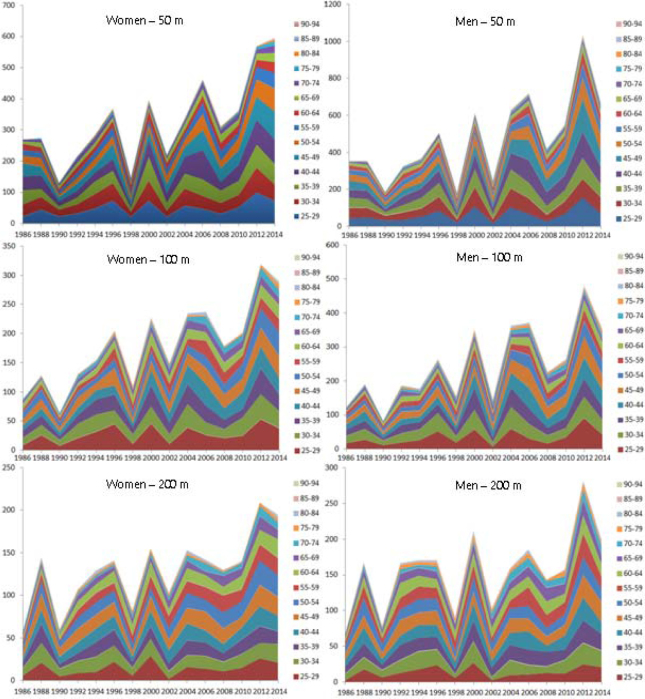

A total of 22,856 master swimmers (9,606 women and 13,250 men) were recorded between 1986 and 2014. In women, 4,935, 2,721, and 1,950 race times were classified in 50 m, 100 m and 200 m, respectively. In men, regarding the before mentioned distances, 7,156, 3,744 and 2,350 race times were recorded, respectively. Figure 1 presents the trend in participation for women and men for all distances from 50 to 200 m. In 50 m, participation increased in women in master groups 35-39 to 75-79 years and in men, in master groups 40-44 to 85-89 years. In 100 m, participation increased in women in master groups 30-34 to 75-79 years, while in men, it increased in groups 40-44 to 85-89 years. In 200 m, participation increased in women in master groups 40-44 to 70-74 years, while in men, the number of athletes increased in master groups 45-49 to 75-79 years. Considering percent changes (Figure 1), the largest increases in participation (i.e. 50% and more) were found at shorter distances (i.e. 50 m) compared to longer ones (i.e. 100 and 200 m). Overall, larger increases were found in younger compared to older age groups for all distances.

Figure 1.

Participation in women and men in master groups from 50 m to 200 m

The men-to-women ratio remained unchanged across master groups from 25-29 to 90-94 years in 50 m (1.43 ± 0.35), 100 m (1.45 ± 0.36) and 200 m (1.33 ± 0.34) (p > 0.05). Across calendar years, the men-to-women ratio remained unchanged at 1.42 ± 0.20, 1.36 ± 0.16 and 1.20 ± 0.14 in 50 m, 100 m and 200 m, respectively (p > 0.05). The men-to-women ratio showed no difference between 50 m and 100 m (p > 0.05). However, it was lower in 200 m compared to 50 m (p = 0.0014) and 100 m (p = 0.0048).

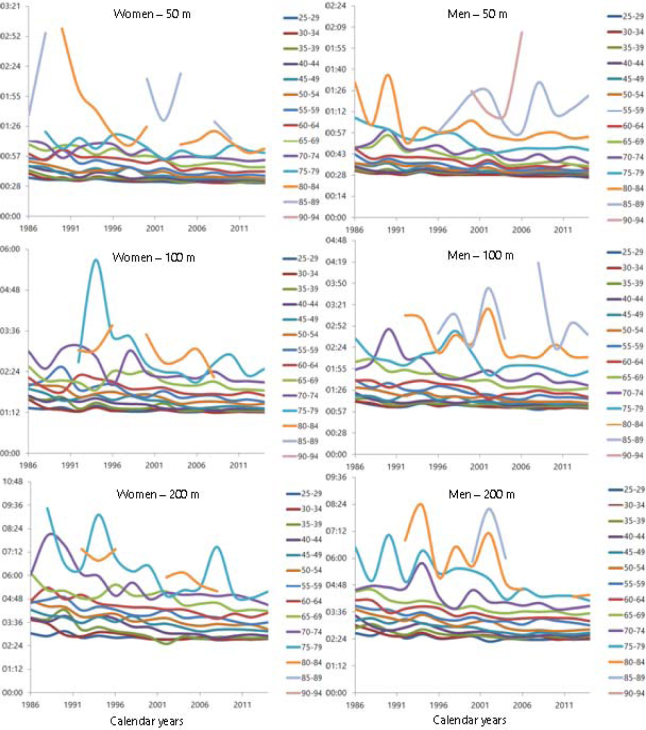

Figure 2 summarizes the race times for women and men for all distances and master groups, while Tables 1 and 2 present the results of the mixed-effects regression analyses. For master groups 25-29 to 90-94 years, women and men improved their performance across years (p < 0.05). For master groups 25-29 to 85-89 years, men were faster than women (p < 0.05), however, it was not the case for the master group 90-94 years. Sex and distance showed a significant interaction in all master groups from 25-29 to 90-94 years for 200 m (p < 0.05). For shorter distances, however, a significant interaction for sex × distance was observed from 25-29 to 75-79 years (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Race times for women and men (min:s) in master groups from 50 m to 200 m

Table 1.

Results of the mixed-effects regression analyses for performance

in age groups 25-29 to 60-64 years

| Estimate | Standard error | df | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25-29 years | |||||

| Constant term | 29.61 | 0.24 | 2806.23 | 121.51 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] | 4.45 | 0.37 | 2813.99 | 11.97 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=200] | 119.44 | 0.51 | 2372.51 | 233.49 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=100] | 35.93 | 0.33 | 1888.43 | 105.82 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=200] | 16.31 | 0.72 | 2248.77 | 22.58 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=100] | 6.05 | 0.51 | 1866.11 | 11.83 | <0.0001 |

| 30-34 years | |||||

| Constant term | 33.61 | 0.63 | 2057.30 | 52.79 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] | 8.96 | 1.02 | 2101.99 | 8.77 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=200] | 153.06 | 1.09 | 1801.43 | 139.52 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=100] | 43.64 | 0.90 | 1444.85 | 48.48 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=200] | 27.62 | 1.64 | 1868.64 | 16.78 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=100] | 11.98 | 1.41 | 1534.07 | 8.47 | <0.0001 |

| 35-39 years | |||||

| Constant term | 30.68 | 0.42 | 2570.92 | 71.94 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] | 6.01 | 0.66 | 2585.17 | 9.06 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=200] | 126.67 | 0.76 | 2063.57 | 165.86 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=100] | 37.50 | 0.57 | 1635.68 | 65.03 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=200] | 23.17 | 1.16 | 2078.93 | 19.86 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=100] | 8.05 | 0.89 | 1663.46 | 8.98 | <0.0001 |

| 40-44 years | |||||

| Constant term | 31.31 | 0.42 | 2674.28 | 74.43 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] | 6.84 | 0.66 | 2690.88 | 10.26 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=200] | 133.64 | 0.82 | 2226.08 | 162.93 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=100] | 38.88 | 0.60 | 1777.90 | 64.49 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=200] | 25.38 | 1.23 | 2261.73 | 20.60 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=100] | 8.31 | 0.963 | 1830.51 | 8.62 | <0.0001 |

| 45-49 years | |||||

| Constant term | 32.27 | 0.46 | 2508.14 | 69.43 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] | 6.97 | 0.73 | 2533.67 | 9.49 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=200] | 139.57 | 0.87 | 2239.03 | 158.68 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=100] | 40.43 | 0.65 | 1723.87 | 61.64 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=200] | 30.51 | 1.28 | 2222.69 | 23.71 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=100] | 10.81 | 1.04 | 1789.17 | 10.38 | <0.0001 |

| 50-54 years | |||||

| Constant term | 33.61 | 0.63 | 2057.30 | 52.79 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] | 8.96 | 1.02 | 2101.99 | 8.77 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=200] | 153.06 | 1.09 | 1801.43 | 139.52 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=100] | 43.64 | 0.90 | 1444.85 | 48.48 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=200] | 27.62 | 1.64 | 1868.64 | 16.78 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=100] | 11.98 | 1.41 | 1534.07 | 8.47 | <0.0001 |

| 55-59 years | |||||

| Constant term | 36.01 | 0.85 | 1596.78 | 42.21 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] | 10.92 | 1.33 | 1610.43 | 8.205 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=200] | 162.69 | 1.24 | 1373.23 | 130.31 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=100] | 47.88 | 1.06 | 1049.13 | 45.12 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=200] | 31.00 | 1.88 | 1320.75 | 16.48 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=100] | 13.27 | 1.64 | 1073.07 | 8.07 | <0.0001 |

| 60-64 years | |||||

| Constant term | 38.85 | 0.97 | 1359.15 | 39.94 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] | 12.88 | 1.53 | 1389.86 | 8.37 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=200] | 173.49 | 1.40 | 1298.88 | 123.81 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=100] | 50.53 | 1.21 | 1050.85 | 41.43 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=200] | 33.47 | 2.12 | 1279.36 | 15.78 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=100] | 15.18 | 1.88 | 1083.97 | 8.06 | <0.0001 |

Table 2.

Results of the mixed-effects regression analyses for performance

in age groups 65-69 to 90-94 years

| Estimate | Standard error | df | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65-69 years | |||||

| Constant term | 41.45 | 1.34 | 1009.07 | 30.82 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] | 16.32 | 2.05 | 999.32 | 7.95 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=200] | 188.09 | 1.79 | 904.56 | 104.76 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=100] | 59.47 | 1.58 | 745.79 | 37.42 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=200] | 38.05 | 2.83 | 905.17 | 13.44 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=100] | 10.50 | 2.46 | 783.09 | 4.25 | <0.0001 |

| 70-74 years | |||||

| Constant term | 45.65 | 2.20 | 704.87 | 20.73 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] | 18.15 | 3.28 | 686.90 | 5.52 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=200] | 203.91 | 2.81 | 573.27 | 72.35 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=100] | 64.19 | 2.43 | 511.50 | 26.35 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=200] | 52.76 | 4.28 | 556.31 | 12.32 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=100] | 18.30 | 3.66 | 511.53 | 4.99 | <0.0001 |

| 75-79 years | |||||

| Constant term | 47.83 | 4.21 | 399.21 | 11.36 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] | 21.00 | 6.60 | 394.75 | 3.18 | 0.002 |

| [distance=200] | 251.39 | 5.89 | 403.62 | 42.62 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=100] | 76.92 | 5.33 | 373.47 | 14.42 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=200] | 54.72 | 9.48 | 384.91 | 5.77 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=100] | 24.04 | 8.38 | 346.83 | 2.86 | 0.004 |

| 80-84 years | |||||

| Constant term | 57.95 | 5.02 | 178.63 | 11.54 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] | 24.48 | 8.10 | 172.74 | 3.02 | 0.003 |

| [distance=200] | 269.15 | 7.94 | 165.36 | 33.86 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=100] | 84.18 | 6.83 | 163.20 | 12.32 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=200] | 37.26 | 12.01 | 155.10 | 3.10 | 0.002 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=100] | 19.40 | 10.71 | 155.14 | 1.81 | 0.072 |

| 85-89 years | |||||

| Constant term | 71.76 | 7.72 | 43.26 | 9.29 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] | 37.86 | 14.44 | 41.10 | 2.62 | 0.012 |

| [distance=200] | 309.61 | 12.24 | 33.66 | 25.27 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=100] | 106.59 | 8.42 | 35.47 | 12.65 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=200] | 113.93 | 29.36 | 32.97 | 3.88 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=100] | 29.67 | 21.56 | 34.42 | 1.37 | 0.178 |

| 90-94 years | |||||

| Constant term | 81.79 | 11.35 | 11.68 | 7.20 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] | 17.61 | 19.66 | 11.68 | 0.89 | 0.388 |

| [distance=200] | 407.94 | 20.11 | 9.28 | 20.28 | <0.0001 |

| [distance=100] | 122.86 | 15.04 | 9.54 | 8.16 | <0.0001 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=200] | 79.62 | 25.39 | 9.01 | 3.13 | 0.012 |

| [sex=women] × [distance=100] | 33.90 | 21.60 | 9.04 | 1.56 | 0.151 |

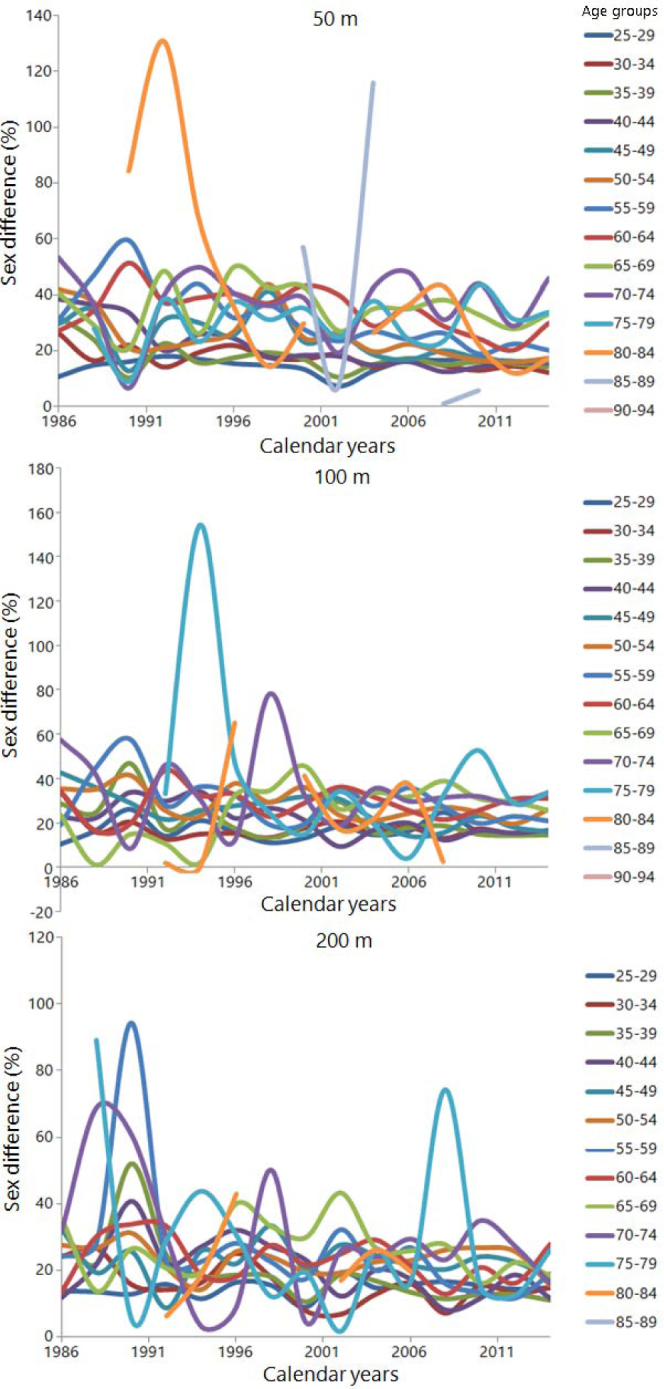

Figure 3 presents the trend in sex difference across years. In 50 m, women reduced the sex difference in master groups 30-34 to 60-64 years (p < 0.05). In 100 m, women decreased the gap to men in master groups 35-39 to 55-59 years (p < 0.05). In 200 m, the sex difference became reduced in master groups 30-34 to 40-44 years (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Sex difference (%) in performance in master groups 25-29 to 90-94 years from 50 m to 200 m

Discussion

This study intended to investigate participation and performance trends in master groups of butterfly swimmers with the hypothesis that participation would increase and performance would improve from the first (Tokyo, 1986) to the last FINA World Masters Championship (Montreal, 2014). The most important findings were that (i) participation increased in master swimmers older than ~30-40 years, (ii) the men-to-women ratio remained unchanged across calendar years and master groups, but it was lower in 200 m compared to 50 and 100 m, (iii) women and men improved performance in all race distances and all master groups, (iv) women were not slower compared to men in the master group 90-94 years, and (v) women reduced the gap to men between ~30 years and ~60 years, although not in younger (< 30 years) or older (> 60 years) master groups.

The first important finding was that the number of successful competitors increased in both women and men preferably in the master groups of 30-40 years and older. In the FINA World Masters Championships, the youngest master group is 25-29 years (http://www.fina.org/discipline/masters). A very likely explanation could be that swimmers of this age still compete in high level races such as the World Championships and the Olympic Games (Allen and Hopkins, 2015; Allen et al., 2014; König et al., 2014). It has been shown that elite butterfly swimmers competing in finals at the World Championships and the Olympic Games are generally ~25 years of age or younger (König et al., 2014). However, the increase in participation is very similar to this observed in other strokes such as freestyle, backstroke and breaststroke. A study investigating participation and performance trends for master freestyle swimmers showed that participation increased in women and men in older age groups (i.e., 40 years and older) (Knechtle et al., 2016a). For backstroke, the increase in participation was more pronounced in older age groups (Unterweger et al., 2016), while for breaststroke, the trend was very similar to freestyle with an increase in participation in athletes older than 40 years (Knechtle et al., 2016b).

Masters swimming is a fast-growing leisure activity, particularly in the United States of America (https://www.usms.org/), Canada (http://mymsc.ca/) and Australia (http://mastersswimming.org.au/), but also in Europe (http://www.len.eu/default.aspx). Marketing, network, funding and culture effects around masters swimming that changed in the last couple of years and the information about this sport discipline reached a worldwide projection. Most towns or cities now have masters clubs. Typically, these are very friendly and welcome newcomers. The minimum requirements to join a masters club vary widely, from the ability to swim one length of the pool to the ability to cover the distance of one kilometre without stopping.

A further aspect might be the increase in life expectancy. For swimmers aged 30-95 years, better health in higher ages and the increase in life expectancy might explain increased participation in master group swimmers. Nowadays, more people live to older ages with better overall functioning (Christensen et al., 2013). Due to better health, elderly people have levels of physical and mental capacities similar to those of younger ones (http://www.who.int/ageing/events/world-report-2015-launch/en/).

Centenarians on average function physically and cognitively as well as 92-93-year-olds due to selective mortality (Christensen et al., 2013). The global share of older people aged 60 years or older increased from 9.2% in 1990 to 11.7% in 2013, and it will continue to grow and is expected to reach ~21.1% by 2050. Globally, the share of older persons aged 80 years or older within the older population was ~14% in 2013 and is estimated to reach ~19% in 2050 (http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2013.pdf). The worldwide number of living nonagenarians and centenarians is growing steadily (http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/). For nonagenarians, their number rose between 1995 and 2010 from 6.71 to 12.12 million. In 2050, this number is expected to reach the value of 71.16 million. For centenarians, their number in Western Europe and Japan grew at an annual rate of about 7% between the 1950s and 1980s, doubling every decade (http://www.popline.org/node/291152). Therefore, it was deduced that the overall increase in participation in FINA World Masters Championships might be due to the increased number of the older general population as well as growing popularity of sports participation.

The second important finding was that the men-to-women ratio remained unchanged across calendar years and master groups, although it was lower in 200 m compared to 50 and 100 m. In other terms, the number of female competitors in 200 m was relatively higher compared to 50 and 100 m. Thus, female master butterfly swimmers were motivated to compete in longer race distances compared to their male counterparts. An explanation of the lower men-to-women ration in 200 m compared to shorter distances might be that women performed relatively better, i.e. reduced gender difference, in 200 m than in shorter distances. Also differences in anthropometric characteristics might explain these findings. Women have higher fat mass and/or higher flexibility compared to men allowing better buoyancy and trunk motion during the race (i.e. culminating with less energy cost through the distance swum) (Tuuri et al., 2002; www.sportsci.org/2014/BMS2014_Abstracts.pdf). The men-to-women ratio was different to freestyle swimmers competing from 50 to 100 m. In these swimmers, the ratio remained unchanged in age groups 25–29 to 75–79 years in 50, 100 and 400 m, but increased in 200 and 800 m. For age groups 80–84 to 85–89 years, the men-to-women ratio remained unchanged in 50 and 100 m, however, it decreased in 200 to 800 m (Knechtle et al., 2016). For backstroke swimmers, there was no consistent trend in the men-to-women ratio (Unterweger et al., 2016). In breaststroke swimmers, the men-to-women ratio remained unchanged for 50 m, 100 m and 200 m (Knechtle et al., 2016b).

The third important finding was that women and men improved performance in all master groups and for all distances. This confirms previous findings for other master athletes such as master marathon runners (Lepers and Cattagni, 2012) and master swimmers (Akkari et al., 2015; Medic et al., 2009). Also in freestyle (Knechtle et al., 2016a), backstroke (Unterweger et al., 2016) and breaststroke (Knechtle et al., 2016b), female and male master swimmers improved race times across years in all age groups and distances. However, this study shows that also octogenarians and nonagenarians improved their performance in swimming, since in the studies of Akkari et al. (2015) and Lepers and Cattagni (2012), the oldest athletes were younger than 80 years. A very likely explanation that these master swimmers improved performance could be their training. Life-long exercise is associated with favorable body composition (Hayes et al., 2013) and a higher level of physical activity is associated with higher skeletal muscle mass (Raguso et al., 2006). For older master swimmer aged 52-82 years, it has been shown that training distance was an important factor for maintaining muscle mass and function in the aging process (Abe et al., 2014). A study investigating French master swimmers showed positive health outcomes in terms of weight management, respiratory function, and vitality due to their race preparation (Potdevin et al., 2015). The improvement in swimming performance in master athletes is in agreement with improvement in elite swimmers. For example, elite butterfly swimmers competing between 1994 and 2011 at national level (Switzerland) improved swimming speed at all distances (Zingg et al., 2014).

Another interesting finding was that men were faster than women from 25 to 89 years, but not from 90-94 years. This finding confirms recent data in master freestyle swimmers where women were slower than men for age groups 25-29 to 75-79 years, but not for age groups 80-84 to 85-89 years (Knechtle et al., 2016).

The very small number of female and male athletes older than 90 years might be the most likely explanation for these findings. The numbers of swimmers of 90 years and older in 50 m, 100 m and 200 m were 9, 4, and 3, respectively. Expressed in percentages of the overall field, the values were 0.0007%, 0.0006% and 0.0007%, respectively. Another explanation could be the higher life expectancy in women compared to men. The older population is predominantly female. Since women tend to live considerably longer than men, older women outnumber older men almost everywhere. In 2013, globally, there were 85 men per 100 women in the master group 60 years or over and 61 men per 100 women in the master group 80 years or over (http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2013.pdf). Considering master swimmers, regular training resulted in more positive health effects in women compared to men (Potdevin et al., 2015). Differences in anthropometric characteristics in elderly women and men might also explain this finding since differences occur between the sexes regarding the age-related loss in skeletal muscle mass. Men older than 70 years lose significantly more fat free mass than women (Fantin et al., 2007). In 68-78 year old women and men, the rate of loss in leg muscle was significantly higher in men than in women (Zamboni et al., 2003). In people older than 80 years, the prevalence of sarcopenia was ~31% in women and ~53% in men (Iannuzzi-Sucich et al., 2002). There are also differences between women and men for fat-free mass with respect to age. Fat-free mass remained stable up to 60 years of age in men and was lower at 75 years of age compared with the younger ages. In women, it was lower from age 60 (Larsson et al., 2015). Furthermore, it was observed that men older than 70 years lost significantly more fat-free mass than women (Fantin et al., 2007). Another study indicated that the fat-free mass index decreased with age in both women and men, although it remained constant among the women with only a 1% decrease up to the age of 84 years (Seino et al., 2015). Our findings differ, however, from the findings of Senefeld et al. (2016) investigating finishing times of the top ten men and women world record performances for butterfly from 1986 to 2011 in 13 5-year age brackets between 25 and 89 years of age. Men were faster than women across all master groups, world record places and distances for all strokes, with the greatest sex difference for butterfly. The most likely explanation for these disparate findings is that Senefeld et al. (2016) considered top ten women and men world record performances until the age of 89 years, while we considered all finishers at the FINA World Masters Championships until the age of 94 years without selection of the top athletes.

The last important finding was that women reduced the gap to men mainly in the middle-aged groups (i.e. 30-64 years), but not in younger and older master groups. Again, our findings differ from those of Senefeld et al. (2016) where sex difference in butterfly swimming speed increased with advanced age. Moreover, the sex difference in performance decreased with longer race distances. Yet again, the most likely explanation is difference between the two samples.

The present study focused on performance trends in master butterfly swimmers who participated in the FINA World Championships. Since the butterfly stroke differs from breaststroke, front crawl and backstroke with regard to swimming energetics and speed (Gatta et al., 2015), start and turns (Veiga et al., 2014) as well as buoyancy (Cohen et al., 2014), caution is needed when generalizing the findings from the butterfly to the other strokes. On the other hand, the findings of this study might help swimming coaches and fitness specialists working with master athletes to develop optimal training programs especially considering gender differences in performance.

In summary, participation increased in master swimmers older than ~30-40 years, the men-to-women ratio remained unchanged across calendar years and master groups, although it was lower in 200 m compared to 50 and 100 m, women and men improved their performance in all race distances and all master groups, women were not slower compared to men in master group 90-94 years, and women reduced the gap to men between ~30 and ~60 years, however, not in younger or older master groups. Based on these findings, we expect a further increase in participation in older master groups and an improvement in performance in these older ages for master butterfly swimmers. For athletes and coaches, we expect a continuous trend in increasing participation and improved performance in master butterfly swimmers. Coaches should be aware of the fact that women at older ages are able to achieve a similar performance to men and therefore, that training of elderly male master swimmers needs adaptations (i.e. elderly men should train with higher intensity compared to elderly women).

Authors submitted their contribution to the article to the editorial board.

References

- Abe T, Kojima K, Stager JM. Skeletal muscle mass and muscular function in master swimmers is related to training distance. Rejuvenation Res. 2014;17:415–421. doi: 10.1089/rej.2014.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadyar B, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Knechtle B. Participation and performance trends in elderly marathoners in four of the world’s largest marathons during 2004-2011. SpringerPlus. 2015;4:465. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1254-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkari A, Machin D, Tanaka H. Greater progression of athletic performance in older Masters athletes. Age Ageing. 2015;44:683–686. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen SV, Hopkins WG. Age of peak competitive performance of elite athletes: A systematic review. Sports Med. 2015;45:1431–1441. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen SV, Vandenbogaerde TJ, Hopkins WG. Career performance trajectories of Olympic swimmers: Benchmarks for talent development. Eur J Sport Sci. 2014;14:643–651. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2014.893020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K, Jeune B, Andersen-Ranberg K, Vaupel JW. More people live to be very old and with a better functioning. Ugeskr Laeger. 2013;175:2395–2398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K, Thinggaard M, Oksuzyan A, Steenstrup T, Andersen-Ranberg K, Jeune B, McGue M, Vaupel JW. Physical and cognitive functioning of people older than 90 years: A comparison of two Danish cohorts born 10 years apart. Lancet. 2013;382:1507–1513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60777-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RCZ, Cleary PW, Harrison SM, Mason BR, Pease DL. Pitching effects of buoyancy during four competitive swimming strokes. J Appl Biomech. 2014;30:609–618. doi: 10.1123/jab.2013-0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa MJ, Barbosa TM, Bragada JA, Marinho DA, Silva AJ. Longitudinal interventions in elite swimming: A systematic review based on energetics, biomechanics, and performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26:2006–2016. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318257807f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenberger E, Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R. Best performances by men and women open-water swimmers during the ‘English Channel Swim’ from 1900 to 2010. J Sports Sci. 2012;30:1295–1301. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2012.709264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantin F, Di Francesco V, Fontana G, Zivelonghi A, Bissoli L, Zoico E, Rossi A, Micciolo R, Bosello O, Zamboni M. Longitudinal body composition changes in old men and women: Interrelationships with worsening disability. J Gerontol - Series A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:1375–1381. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.12.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatta G, Benelli P, Ditroilo M. The decline of swimming performance with advancing age: A cross-sectional study. J Strength Cond Res. 2006;20:932–938. doi: 10.1519/R-18845.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatta G, Cortesi M, Fantozzi S, Zamparo P. Planimetric frontal area in the four swimming strokes: Implications for drag, energetics and speed. Hum Mov Sci. 2015;39:41–54. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley AA, Hartley JT. Age differences and changes in sprint swimming performances of masters athletes. Exp Aging Res. 1986;12:65–70. doi: 10.1080/03610738608259438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes LD, Grace FM, Sculthorpe N, Herbert P, Kilduff LP, Baker JS. Does chronic exercise attenuate age-related physiological decline in males? Res Sports Med. 2013;21:343–354. doi: 10.1080/15438627.2013.825799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannuzzi-Sucich M, Prestwood KM, Kenny AM. Prevalence of sarcopenia and predictors of skeletal muscle mass in healthy, older men and women. J Gerontol - Series A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M772–M777. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.12.m772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B, Nikolaidis PT, König S, Rosemann T, Rüst CA. Performance trends in master freestyle swimmers aged 25-89 years at the FINA World Championships from 1986 to 2014. Age (Dordr) 38:2016a. 18. doi: 10.1007/s11357-016-9880-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B, Nikolaidis PT, Rosemann T, Rüst CA. Performance trends in age group breaststroke swimmers in the FINA World Championships 1986-2014. Chin J Physiol. 2016b;59:247–259. doi: 10.4077/CJP.2016.BAE406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B, Rosemann T, Lepers R, Rüst CA. Women outperform men in ultradistance swimming: The Manhattan Island Marathon Swim from 1983 to 2013. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2014;9:913–924. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2013-0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knechtle B, Rosemann T, Rüst CA. Women cross the ‘Catalina Channel’ faster than men. Springerplus. 2015;4:332. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König S, Valeri F, Wild S, Rosemann T, Rüst CA, Knechtle B. Change of the age and performance of swimmers across World Championships and Olympic Games finals from 1992 to 2013 – a cross-sectional data analysis. SpringerPlus. 2014;3:652. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson I, Lissner L, Samuelson G, Fors H, Lantz H, Näslund I, Carlsson LM, Sjöström L, Bosaeus I. Body composition through adult life: Swedish reference data on body composition. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69:837–842. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepers R, Cattagni T. Do older athletes reach limits in their performance during marathon running? Age (Dordr) 2012;34:773–781. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9271-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medic N, Young BW, Starkes JL, Weir PL, Grove JR. Gender, age, and sport differences in relative age effects among us masters swimming and track and field athletes. J Sports Sci. 2009;27:1535–1544. doi: 10.1080/02640410903127630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potdevin F, Vanlerberghe G, Zunquin G, Peze T, Theunynck D. Evaluation of global health in master swimmers involved in French National Championships. Sports Med Open. 2015;1:12. doi: 10.1186/s40798-015-0021-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raguso CA, Kyle U, Kossovsky MP, Roynette C, Paoloni-Giacobino A, Hans D, Genton L, Pichard C. A 3-year longitudinal study on body composition changes in the elderly: Role of physical exercise. Clin Nutr. 2006;25:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seino S, Shinkai S, Iijima K, Obuchi S, Fujiwara Y, Yoshida H, Kawai H, Nishi M, Murayama H, Taniguchi Y, Amano H, Takahashi R. Reference values and age differences in body composition of community-dwelling older Japanese men and women: A pooled analysis of four cohort studies. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senefeld J, Joyner MJ, Stevens A, Hunter SK. Sex differences in elite swimming with advanced age are less than marathon running. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016;26:17–28. doi: 10.1111/sms.12412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuuri G, Loftin M, Oescher J. Association of swim distance and age with body composition in adult female swimmers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:2110–2114. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200212000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unterweger C, Knechtle B, Nikolaidis PT, Rosemann T, Rüst CA. Increased participation and improved performance in age group backstroke master swimmers from 25-29 to 100-104 years at the FINA World Masters Championships from 1986-2014. SpringerPlus. 2016;5:645. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2209-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga S, Cala A, Frutos PG, Navarro E. Comparison of starts and turns of national and regional level swimmers by individualized-distance measurements. Sports Biomech. 2014;13:285–295. doi: 10.1080/14763141.2014.910265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt P, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R, Knechtle B. Analysis of 10 km swimming performance of elite male and female open-water swimmers. SpringerPlus. 2013;2:1–15. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfrum M, Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R. The effects of course length on freestyle swimming speed in elite female and male swimmers - a comparison of swimmers at national and international level. SpringerPlus. 2013;2:1–12. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboni M, Zoico E, Scartezzini T, Mazzali G, Tosoni P, Zivelonghi A, Gallagher D, De Pergola G, Di Francesco V, Bosello O. Body composition changes in stable-weight elderly subjects: The effect of sex. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003;15:321–327. doi: 10.1007/BF03324517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamparo P, Gatta G, Di Prampero PE. The determinants of performance in master swimmers: An analysis of master world records. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112:3511–3518. doi: 10.1007/s00421-012-2332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingg MA, Wolfrum M, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R, Knechtle B. Freestyle versus butterfly swimming performance-effects of age and sex. Hum Mov. 2014;15:25–35. [Google Scholar]