Abstract

Temozolomide (TMZ) is an alkylating chemotherapeutic agent widely used in anti-glioma treatment. However, acquired TMZ resistance represents a major clinical challenge that leads to tumor relapse or progress. This study investigated the genomic profiles including long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) and mRNA expression associated with acquired TMZ resistance in glioblastoma (GBM) cells in vitro. The TMZ-resistant (TR) of GBM sub-cell lines were established through repetitive exposure to increasing TMZ concentrations in vitro. The differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs between the parental U87 and U87TR cells were detected by human lncRNA microarray method. In this study, we identified 2,692 distinct lncRNAs demonstrating >2-fold differential expression with 1,383 lncRNAs upregulated and 1,309 lncRNAs downregulated. Moreover, 4,886 differential mRNAs displayed 2,933 mRNAs upregulated and 1,953 mRNAs downregulated. Further lncRNA classification and subgroup analysis revealed the potential functions of the lncRNA-mRNA relationship associated with the acquired TMZ resistance. Gene ontology and pathway analysis on mRNAs showed significant biological regulatory genes and pathways involved in acquired TMZ resistance. Moreover, we found the ECM-receptor interaction pathway was significantly downregulated and ECM related collagen I, fibronectin, laminin and CD44 were closely associated with the TR phenotype in vitro. Our findings indicate that the dysregulated lncRNAs and mRNAs identified in this work may provide novel targets for overcoming acquired TMZ resistance in GBM chemotherapy.

Keywords: long non-coding RNA, mRNA, temozolomide, resistance, glioblastoma

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is one of the most devastating malignant neoplasms in the central nervous system with increasing risk and incidence (1). Despite recent therapeutic advances, the prognosis of patients afflicted by GBM remains poor, even with multimodal therapy including maximal surgical resection followed by concurrent radiation and chemotherapy with alkylating drugs (2). Temozolomide (TMZ), an oral alkylating agent used as the first-line therapy for GBM treatment, is frequently limited in durability of treatment response because of acquired drug resistance (3). Thus, identifying novel mechanisms underlying acquired TMZ resistance may allow for a more durable benefit from the anti-glioma properties of TMZ (4).

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), longer than 200 bp in length and lacking significant protein coding open reading frames, transcribed from intergenic and intronic regions in human genome and participating in various biological or pathological processes including cancers (5,6). In the past few years, deregulated lncRNA has been widely reported to be involved in cancer occurrence, progression and metastasis (7–9). Evidence linking lncRNAs to tumor drug resistance have also emerged (10–12). For instance, lncRNA UCA1 enhanced cisplatin resistance in bladder cancer by CREB activation (13), and lncRNA GAS5 downregulation causes trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer (14). However, few studies have focused on the occurrence and development of TMZ resistance in GBM related to lncRNAs.

In this study, we profiled the expression of lncRNAs and mRNAs in U87 TMZ-resistant (U87TR) cells compared to the parental cells by microarray method. We showed various differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs and found multiple dysregulated signal pathways that associated with TMZ resistance. These findings may provide us novel insights and potential targets for overcoming acquired TMZ resistance in GBM chemotherapy.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and TR cell establishment

The human GBM cell line U87 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA) and U251 was purchased from the CLS Cell Lines Service GmbH (Eppelheim, Germany). The TR cells were generated by repetitive pulse exposure of U87 and U251 GBM cells to TMZ (48 h every 2 weeks) and with increasing TMZ concentrations for 6 months. For TR phenotype maintenance, U87TR and U251TR cells were alternately treated with TMZ (500 µM) for 48 h. The corresponding methods were mainly based on the previous study of Monoz et al (15–17) and with minor adjustment in this study. The parental and TR cells were maintained in DMEM (Hyclone, USA) with 10% (v/v) FBS (Hyclone) and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, USA) at 37°C in 5% CO2 humidified air incubator (Thermo Scientific, USA).

Cell survival assay

The parental and TR cells were plated in 96-well plate and treated with TMZ in different concentrations, respectively. After 48-h incubation, cells were replaced with fresh medium with CCK-8 solution (v/v 10%; Dojindo, Japan) and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Then the absorbance was measured at 450 nm (reference, 620 nm) using Multiscan GO microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Finland). Cells without TMZ treatment were set as the control and the result was shown as cell viability ratio towards the control group.

RNA extraction and qPCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted by TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) and the absorbance was measured with OD260/280 ratio higher than 1.8. For qPCR analysis, 1 µg total RNA was subjected to the synthesis of cDNA by using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific, Germany). Reactions were initiated by incubation at 65°C for 5 min, followed by 60 min at 42°C and terminated the reaction by heating at 70°C for 5 min. The cDNA performed to PCR by using the Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific, Germany). Total reaction volume (25 µl) included 12.5 µl mix (2X), 1.5 µl (10 mM) primers (Table I) synthesized by Sangon Biological Engineering Technology and Services Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), 8.5 µl nuclease-free water and 0.8 µg/1 µl cDNA. PCR reaction was run in Step-one Plus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Germany) and analyzed using Step-one software. The qPCR protocol contained initial denaturation at 95°C 10 min, then 40 cycles including 95°C for 5-sec denaturation, 60°C for 30 sec annealing and 72°C for 30-sec extension. qPCR assays were carried out in triplicate, and the specificity of the PCR products was verified with melting curve analysis. The amount of each respective amplification product was determined relative to the gene β-actin. The fold change in gene expression relative to control was calculated by 2−ΔΔCT (18).

Table I.

Primers used to perform qPCR analysis.

| mRNA name | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| ABCB1 | CCCATCATTGCAATAGCAGG | TGTTCAAACTTCTGCTCCTGA |

| ABCC | ATGTCACGTGGAATACCAGC | GAAGACTGAACTCCCTTCCT |

| BCRP | ATGTCACGTGGAATACCAGC | GAAGACTGAACTCCCTTCCT |

| MGMT | ACCGTTTGCGACTTGGTACTT | GGAGCTTTATTTCGTGCAGACC |

| DNMT1 | ACCAGGGAGAAGGACAGG | CTCACAGACGCCACATCG |

| TP53 | GTGGTGGTGCCCTATGAG | TGTTCCGTCCCAGTAGATTA |

| HIF-1A | CATCTCCATCTCCTACCCACA | CTTTTCCTGCTCTGTTTGGTG |

| CA9 | GCTGCTTCTGGTGCCTGTC | GGAGCCCTCTTCTTCTGATTTA |

| Bcl2L1 | TGGAACTCTATGGGAACAATG | TGAGCCCAGCAGAACCAC |

| VEGFA | TTGCCTTGCTGCTCTACC | ATGTCCACCAGGGTCTCG |

| GAPDH | GACCTGACCTGCCGTCTA | AGGAGTGGGTGTCGCTGT |

Microarray profiling and data analysis

For microarray, Arraystar Human LncRNA Microarray V3.0 covering ~30,586 lncRNAs and 26,109 coding transcripts was designed to detect the profile of human lncRNAs and protein-coding transcripts. Sample labeling and array hybridization were performed according to the Agilent One-Color Microarray-Based Gene Expression Analysis protocol (Agilent Technology). The array images were further analyzed by Agilent Feature Extraction software (version 11.0.1.1). Quantile normalization and subsequent data processing were applied with GeneSpring GX v11.5.1 software (Agilent Technologies). Distinct lncRNAs and mRNAs between U87 and U87TR were presented by hierarchical clustering and volcano plot filtering. The gene ontology (GO) analysis and pathway analysis were performed in the standard enrichment computation method according to the latest KEGG database (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, http:/www.genome.jp/kegg).

Western blot analysis

Total protein of cells was extracted by Cell Lysis and Protein Extraction kit (Keygen Biotech Co., China) and concentration was measured by a BCA Protein Detection kit (Keygen Biotech). Total protein (40 µg) was subjected to 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore Corp., USA). The blots were blocked for 1 h at RT with 5% non-fat milk (Bio-Rad, USA) in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) and probed with following primary antibodies: MDR1/ABCB1(E1Y7B) (142 kDa), MRP1/ABCC1(D708N) (173 kDa), ABCG (66 kDa) (Cell Signaling Technology, USA), MGMT (25 kDa), collagen I (139 kDa), fibronectin (262 kDa), laminin (198 kDa) (Abcam, USA), CD44 (82 kDa) (Abnova, USA) in 5% non-fat milk in TBST overnight at 4°C. Anti-GAPDH antibody (37 kDa) (Cell Signaling Technology) was used as a loading control. Subsequently, the blots were washed in TBST and incubated with goat anti-rabbit or mouse IgG (H+L) horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Fdbio, China) for 1 h at RT. Then the blots were washed with TBST and visualized using Immobilon Western HRP Substrate (Millipore).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

During 3-day TMZ treatment, the culture supernatants of U87 and U87TR cells were collected respectively and the level of total collagen I was measured with Collagen I ELISA kit (R&D Systems, USA). The assay was carried out as recommended by the kit protocol.

Immunofluorescence staining

For immunofluorescence analysis, GBM cells were seeded on glass coverslips (0.17 mm thickness, 14 mm diameter) in 6-well plate overnight and then treated with TMZ for 3 days, respectively. After treatments, cells were performed by PBS washing, 4% paraformaldehyde fixation (30 min), 0.1% Triton X-100 permeating (5 min) and 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) blocking (30 min). Then the cells were incubated with anti-collagen I antibody (1:2,000) and anti-CD44 antibody (1:1,000) diluted in 2% BSA at 4°C overnight. After 3 times PBS rinsing, appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies were added to cell samples and incubated at 37°C in the dark for 1 h. Coverslips were mounted on slides using mounting medium (Santa Cruz, USA) containing DAPI DNA counterstain. Images were captured by a fluorescence microscopy (IX-70, Olympus, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for three separate experiments and analyzed by SPSS 13.0 software with two-sample t-test assuming unequal variances. p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

TMZ-resistant phenotype in U87TR and U251TR cells

U87 and U251 GBM cells were repetitively pulse-exposed to increasing TMZ concentrations for 6 months until a stable resistant phenotype was obtained. Through light microscopy, we observed that the cellular morphology of U87TR and U251TR cells differed from its parental cells with larger, irregular morphology and long protrusions (Fig. 1A–D), especially in U87TR cells. To examine the chemoresistant properties, CCK-8 assay was used to characterize chemosensitivity of these cells to TMZ. We noted that TMZ led to a concentration-dependent decrease in both TR and parental cells and the TR cells showed higer resistant level towards TMZ (U87TR 1.74±0.15 mM, U251TR 2.43±0.01 mM) when compared to its conterpart parental cells (Fig. 1E). Additionally, the expression of related multidrug-resistant (MDR) phenotypes was also analyzed by qPCR and western blot analyses. As shown in Fig. 1F and G, we found the expression of ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABCB1, ABCC and BCRP) and MGMT were significantly upregulated in TR cells and further protein analysis comfirmed these results (Fig. 1H). Together, we demonstrated that repetitive pulse-exposure of TMZ to GBM cells could establish stable TR phenotype and these sublines were suitable for further experiments.

Figure 1.

TMZ-resistant phenotype in U87TR and U251TR cells. The cellular morphology of U87, U87TR cells (A and B) and U251, U251TR cells (C and D), scale bar, 250 µM. The parental and TR cells were plated in 96-well plate and treated with TMZ in different concentrations. After 48-h incubation, CCK-8 assay was applied to analyze the chemosensitivity of parental and TR cells to TMZ (E). qPCR analysis of multidrug-resistant phenotype (ABCB1, ABCC1 and BCRP) and MGMT gene expression in U87TR and U251TR cells compared to the parental cells (F and G), *p<0.05 vs. U87 or U251 parental cells. Western blot analysis of MDR phenotype and MGMT expression in GBM parental and TR cells (H).

Differential expression of lncRNAs and mRNAs in U87TR compared to U87 cells

Arraystar probe dataset was applied to screen differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs in U87 and U87TR cells. After normalization and data filtering (Fig. 2A–C and E–G), we found that 2,692 distinct lncRNAs demonstrated >2-fold differential expression with 1,383 lncRNAs upregulated and 1,309 lncRNAs downregulated (Fig. 2D), whereas, 4,886 differential mRNAs displayed 2,933 mRNAs upregulated and 1953 mRNAs downregulated which was shown by the hierarchical clustering (fold change ≥2.0 and p-value ≤0.05) (Fig. 2H). The top 10 significantly and dominant dysregulated lncRNAs and mRNAs are listed (Tables II and III). Among the distinct lncRNAs, there were 1,410 intergenic, 284 intronic antisense, 409 natural antisense, 173 bidirectional, 238 exon sense and 173 intron sense-overlapping (Fig. 2I). Additionally, the chromosomal imbalances associated with drug resistance was analyzed and aberrantly expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs located on chromosome 1 were uneven with 8.90% in lncRNA and 10.02% in mRNA (Fig. 2J and K).

Figure 2.

Differentially expressed lncRNA and mRNA profiles in U87TR cells. The box plot, scatter plot and volcano plot were used for quality assessment of lncRNA (A–C) and mRNA (E–G) data after filtering. The hierarchical clustering and heat map of lncRNA (D) and mRNAs (H) expression between U87 and U87TR. The relative higher expression levels are indicated with red and lower with green. The subgroups of distinctly expressed lncRNAs categorized by relationship (I) and distribution of aberrantly expressed lncRNA (J) and mRNA (K) profiles on human chromosomes.

Table II.

Top 10 up- and downregulated lncRNAs in U87TR cells.

| Seqname | Gene symbol | Fold change | Chromosome strand | Relationship | p-value | Up/down |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENST00000443252 | AL132709.5 | 239.63 | chr14+ | Intergenic | 4.79E-08 | Up |

| uc010ahe.1 | BC041856 | 141.54 | chr14− | Intergenic | 2.58E-05 | Up |

| TCONS_00008977 | XLOC_003829 | 99.74 | chr4+ | Intergenic | 1.76E-05 | Up |

| TCONS_00022632 | XLOC_010933 | 64.73 | chr14+ | Intergenic | 1.27E-06 | Up |

| ENST00000556720 | AL132709.5 | 59.33 | chr14+ | Intergenic | 1.19E-07 | Up |

| ENST00000513211 | RP11-734I18.1 | 48.96 | chr4+ | Intergenic | 1.16E-07 | Up |

| TCONS_00027642 | XLOC_013181 | 47.55 | chr19+ | Intergenic | 9.62E-06 | Up |

| ENST00000570409 | RP11-461A8.4 | 46.57 | chr16− | Intronic antisense | 5.7E-06 | Up |

| ENST00000547898 | RP11-328C8.5 | 45.69 | chr12− | Intron sense | 2.39E-05 | Up |

| ENST00000442197 | AL132709.8 | 44.46 | chr14+ | Intergenic | 4.36E-05 | Up |

| NR_033869 | LOC401164 | 264.52 | chr4+ | Intergenic | 9.29E-05 | Down |

| NR_038848 | LOC643401 | 181.11 | chr5+ | Intergenic | 0.000837 | Down |

| ENST00000565689 | RP11-941F15.1 | 176.55 | chr15− | Intergenic | 6.18E-05 | Down |

| ENST00000444963 | AC018866.1 | 171.92 | chr2− | Intergenic | 2.82E-05 | Down |

| uc003jgv.2 | LOC643401 | 137.76 | chr5+ | Intergenic | 7.83E-05 | Down |

| uc003jgx.2 | LOC643401 | 136.05 | chr5+ | Intergenic | 0.000304 | Down |

| ENST00000503458 | RP11-219G10.3 | 120.27 | chr4+ | Intergenic | 2.19E-06 | Down |

| ENST00000421067 | RP11-83J21.3 | 90.59 | chr9+ | Intronic antisense | 6.65E-05 | Down |

| ENST00000421067 | RP11-83J21.3 | 90.59 | chr9+ | Intronic antisense | 6.65E-05 | Down |

| ENST00000578278 | RP11-146G7.3 | 77.20 | chr18− | Intergenic | 3.3E-06 | Down |

Table III.

Top 10 up- and downregulated mRNAs in U87TR cells.

| Gene symbol | Fold change | Up/down | p-value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL18 | 490.19 | Up | 5.32535E-07 | Interleukin 18 (interferon-γ-inducing factor) |

| ZNF93 | 394.98 | Up | 3.9652E-06 | Zinc finger protein 93 |

| MTAP | 371.14 | Up | 9.4726E-07 | S-methyl-5′-thioadenosine phosphorylase |

| ZNF254 | 182.70 | Up | 5.17967E-06 | Zinc finger protein 254 |

| SOX2 | 129.30 | Up | 3.85212E-06 | Transcription factor SOX-2 |

| ZNF765 | 121.16 | Up | 2.0173E-06 | Zinc finger protein 765 |

| ZNF845 | 120.54 | Up | 6.692E-06 | Zinc finger protein 845 |

| ZNF611 | 118.25 | Up | 8.22434E-08 | Zinc finger protein 611 |

| GPR160 | 106.29 | Up | 5.8696E-06 | Probable G-protein coupled receptor 160 |

| ZNF675 | 99.27 | Up | 1.49803E-05 | Zinc finger protein 675 |

| TFPI2 | 607.04 | Down | 5.48207E-06 | Tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 precursor |

| BAALC | 471.68 | Down | 2.4074E-05 | Brain and acute leukemia cytoplasmic protein 2 |

| DPP4 | 330.97 | Down | 2.21878E-05 | Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 |

| AHR | 292.93 | Down | 2.83673E-05 | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor precursor |

| KYNU | 255.58 | Down | 6.99952E-05 | Kynureninase isoform b |

| BDKRB1 | 206.12 | Down | 3.58205E-06 | B1 bradykinin receptor |

| FOXD1 | 168.72 | Down | 6.46324E-05 | Forkhead box protein D1 |

| EREG | 165.81 | Down | 1.73919E-05 | Proepiregulin preproprotein |

| KYNU | 161.95 | Down | 1.72429E-05 | Kynureninase isoform a |

| DCN | 142.10 | Down | 1.4439E-05 | Decorin isoform b precursor |

LncRNAs classification and subgroup analysis

For further investigation of potential-function of lncRNAs, lncRNAs classification and subgroup analysis were conducted. According to the Gencode annotation, lncRNAs were devided into enhancer-like lncRNAs, large intergenic non-coding RNAs (lincRNAs) and HOX lncRNAs. In enhancer lncRNA profiling, we found 108 distinct enhancer lncRNAs with 266 nearby coding genes transcription (distance <300 kb) and among these lncRNA-mRNA relationships, up-up direction (87 pairs), up-down direction (67 pairs), down-up direction (56 pairs), down-down direction (56 pairs) (Table IV). However, in lincRNA profiling, there were 809 distinct lincRNAs with 1,918 differentially expressed nearby coding genes (distance <300 kb) including up-up direction (814 pairs), up-down direction (272 pairs), down-up direction (394 pairs) and down-down direction (438 pairs) of lncRNA-mRNA relationship (Table V). The data also showed 125 HOX cluster transcribed regions in the four human HOX loci of both lncRNAs and coding transcripts including 48 coding transcripts and 77 non-coding transcripts (Table VI).

Table IV.

Top 10 distinct enhancer lncRNAs near the coding gene data.

| Gene symbol | Fold change | Regulation - lncRNAs | Genome relationship | Nearby gene | Fold change | Regulation - mRNAs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP11-346D6.6 | 39.582054 | Up | Downstream | PRKG1 | 38.59571 | Down |

| RP11-346D6.6 | 39.582054 | Up | Downstream | PRKG1 | 10.437759 | Down |

| RP11-346D6.6 | 39.582054 | Up | Downstream | DKK1 | 2.0498126 | Up |

| RP4-737E23.2 | 39.0317 | Down | Downstream | NXT1 | 2.1266758 | Up |

| RP4-737E23.2 | 39.0317 | Down | Downstream | GZF1 | 2.2363193 | Up |

| AX746690 | 28.182703 | Up | Upstream | ADIG | 5.036083 | Down |

| RP13-16H11.2 | 27.392548 | Down | Upstream | ABI1 | 2.0226862 | Down |

| RP13-16H11.2 | 27.392548 | Down | Upstream | ABI1 | 2.0447593 | Down |

| RP13-16H11.2 | 27.392548 | Down | Upstream | ABI1 | 2.2119737 | Down |

| RP11-117P22.1 | 25.868437 | Up | Upstream | AKR1C1 | 5.1898365 | Down |

| RP11-445H22.4 | 20.70799 | Down | Downstream | ADA | 2.115311 | Down |

| RP11-445H22.4 | 20.70799 | Down | Downstream | PKIG | 2.4809623 | Down |

| RP11-445H22.4 | 20.70799 | Down | Upstream | WISP2 | 2.2126765 | Down |

| XXyac-YM21GA2.4 | 20.248714 | Down | Upstream | CTSL1 | 4.7252097 | Down |

| RP11-160A10.2 | 15.469184 | Down | Upstream | CLVS2 | 8.49382 | Down |

| LOC285758 | 14.293567 | Up | Downstream | MARCKS | 2.3576546 | Up |

| LOC285758 | 14.293567 | Up | Upstream | HDAC2 | 2.666347 | Up |

| RP11-14N7.2 | 13.172412 | Down | Upstream | NBPF16 | 2.5870576 | Up |

Table V.

Top 10 distinct lincRNAs near the coding gene data.

| Gene symbol | Fold change | Regulation lncRNAs | Genome relationship | Nearby gene | Fold change mRNAs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP11-941F15.1 | 176.5588 | Down | Downstream | CD276 | 3.1752949 |

| RP11-146G7.3 | 77.20038 | Down | Downstream | ARHGAP28 | 5.5441136 |

| RP11-554A11.4 | 64.153145 | Down | Downstream | CPT1A | 3.7187796 |

| RP11-554A11.4 | 64.153145 | Down | Downstream | CPT1A | 2.3309202 |

| RP11-554A11.4 | 64.153145 | Down | Upstream | MRGPRF | 2.9983652 |

| RP11-113C12.3 | 52.048756 | Down | Upstream | C3AR1 | 4.6431336 |

| XLOC_013181 | 47.557842 | Up | Downstream | ZNF8 | 3.150816 |

| XLOC_013181 | 47.557842 | Up | Downstream | TRIM28 | 2.829188 |

| XLOC_013181 | 47.557842 | Up | Downstream | ZNF324 | 2.4305477 |

| XLOC_013181 | 47.557842 | Up | Upstream | ZNF544 | 30.045504 |

| XLOC_013181 | 47.557842 | Up | Upstream | ZNF274 | 2.003165 |

| XLOC_013181 | 47.557842 | Up | Upstream | ZNF274 | 4.3925347 |

| PRORSD1P | 46.21162 | Down | Upstream | RTN4 | 2.7800567 |

| PRORSD1P | 46.21162 | Down | Upstream | RTN4 | 2.2093842 |

| PRORSD1P | 46.21162 | Down | Upstream | CLHC1 | 2.0670087 |

| PRORSD1P | 46.21162 | Down | Upstream | RTN4 | 3.4394581 |

| AC003092.1 | 43.996338 | Down | Upstream | BET1 | 2.096403 |

| AC003092.1 | 43.996338 | Down | Upstream | TFPI2 | 607.0495 |

| AK123141 | 43.92919 | Up | Downstream | ZNF680 | 5.060253 |

| AK123141 | 43.92919 | Up | Downstream | ZNF680 | 29.15355 |

| AK123141 | 43.92919 | Up | Upstream | ZNF736 | 11.060797 |

| AK123141 | 43.92919 | Up | Upstream | ZNF679 | 3.0256562 |

| AK123141 | 43.92919 | Up | Upstream | ZNF727 | 39.63797 |

| AK123141 | 43.92919 | Up | Upstream | ZNF735 | 4.4493775 |

| RP11-346D6.6 | 39.582054 | Up | Downstream | PRKG1 | 38.59571 |

| RP11-346D6.6 | 39.582054 | Up | Downstream | PRKG1 | 10.437759 |

| RP11-346D6.6 | 39.582054 | Up | Downstream | DKK1 | 2.0498126 |

| RP4-737E23.2 | 39.0317 | Down | Downstream | NXT1 | 2.1266758 |

| RP4-737E23.2 | 39.0317 | Down | Downstream | GZF1 | 2.2363193 |

Table VI.

HOX cluster profiling (part).

| Probe name | Seqname | Gene symbol | Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASHGA5P021981 | NM_014212 | HOXC11 | Homeobox protein Hox-C11 |

| ASHGA5P053003 | NM_006735 | HOXA2 | Homeobox protein Hox-A2 |

| ASHGA5P005899 | NM_024017 | HOXB9 | Homeobox protein Hox-B9 |

| ASHGA5P032505 | NM_024015 | HOXB4 | Homeobox protein Hox-B4 |

| ASHGA5P036264 | NM_002148 | HOXD10 | Homeobox protein Hox-D10 |

| ASHGA5P053006 | NM_006896 | HOXA7 | Homeobox protein Hox-A7 |

| ASHGA5P036265 | NM_014213 | HOXD9 | Homeobox protein Hox-D9 |

| ASHGA5P032508 | NM_032391 | PRAC | small nuclear protein PRAC |

| ASHGA5P032507 | NM_004502 | HOXB7 | Homeobox protein Hox-B7 |

| ASHGA5P036262 | NM_021192 | HOXD11 | Homeobox protein Hox-D11 |

| ASHGA5P042956 | NM_024014 | HOXA6 | Homeobox protein Hox-A6 |

| ASHGA5P028030 | NM_017410 | HOXC13 | Homeobox protein Hox-C13 |

| ASHGA5P001267 | NM_018952 | HOXB6 | Homeobox protein Hox-B6 |

| ASHGA5P055442 | NM_153693 | HOXC6 | Homeobox protein Hox-C6 isoform 2 |

| ASHGA5P042958 | NM_005523 | HOXA11 | Homeobox protein Hox-A11 |

| ASHGA5P006323 | NM_030661 | HOXA3 | Homeobox protein Hox-A3 isoform a |

GO and pathway analysis of differentially expressed mRNAs

Previous studies have revealed that the coding and non-coding RNA can interact with each other in gene expression and dictate final protein output (19,20). To better understand the function of distinct lncRNAs, we first performed GO function analysis associating differentially expressed mRNAs with GO categories. The GO categories were generally comprised of 3 structured networks: biological processes, cellular components and molecular function (21). In our study, the differentially expressed mRNAs were mainly enriched for GO terms related to the nucleic acid metabolic process and response to chemical stimulus involved in biological processes, nucleus and extracellular region part involved in cellular components as well as nucleic acid binding and protein binding involved in molecular function (Figs. 3A–C and 4A–C).

Figure 3.

GO and pathway analysis on functional classification of upregulated genes. GO categories cover three domains: biological process (A), cellular component (B) and molecular function (C). Analysis of significantly upregulated pathways (D). The (−log10) p-value indicates the significance of pathway correlated enrichment in the differentially expressed mRNAs.

Figure 4.

GO and pathway analysis on functional classification of downregulated genes. GO categories cover three domains: biological process (A), cellular component (B) and molecular function (C). Analysis of significant downregulated pathways (D). The (−log10) p-value indicates the significance of pathway correlated enrichment in the differentially expressed mRNAs.

To identify significant pathways associated with TMZ resistance, pathway analysis was applied for the differentially expressed mRNAs. We found a total of 97 pathways that showed significant differences with 28 upregulated and 69 downregulated pathways. The top 3 upregulated pathways were pyrimidine metabolism, RNA transport and DNA replication signaling while the top 3 downregulated pathways were rheumatoid arthritis, ECM-receptor interaction and leishmaniasis signaling. The predominant pathways are shown in (Figs. 3D and 4D) and it is noteworthy that the validated MMR and NER pathways, which associated with TMZ resistance, were upregulated with the false discovery rate of Pathway ID at 2.298×10−5 and 9.769×10−4, respectively (Table VII).

Table VII.

Significant pathways associated with TMZ resistance.

| Pathway ID | Definition | Fisher p-value | FDR | Enrichment score | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa03430 | Mismatch repair (MMR) | 7E-07 | 2E-05 | 6.16 | EXO1/LIG1/MLH1/MSH3/PCNA/POLD2/POLD3/RFC2/RFC3/RFC4/RFC5/RPA1/RPA2 |

| hsa03420 | Nucleotide excision repair (NER) | 3E-05 | 0.001 | 4.48 | ERCC1/ERCC2/ERCC3/ERCC8/POLD3/POLE/POLE2/RFC2/RFC3/RFC4/RFC5/RPA1/RPA2 |

| hsa04512 | ECM-receptor interaction | 2E-07 | 3E-05 | 6.60 | CD44/CD47/COL1A1/COL1A2/COL3A1/COL4A5/COL5A1/COL5A2/COL6A1/COL6A2/COL6A3/FN1/HSPG2/ITGA1/ITGA11/ITGA5/ITGAV/ITGB1/LAMA2/LAMA4/LAMC1/LAMC2/SPP1 |

Downregulation of ECM-receptor interaction pathway associated with TR phenotype

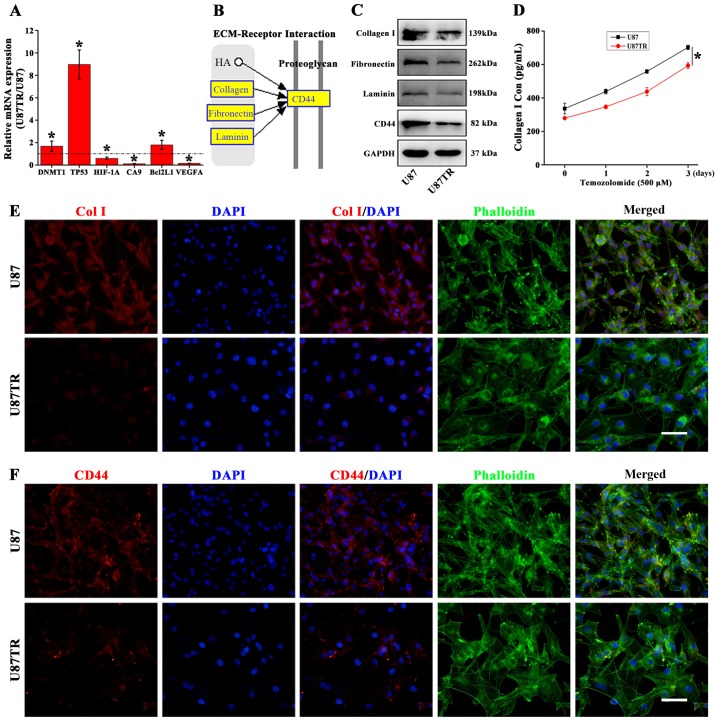

For microarray profile validation, six mRNAs (DNMT1, TP53, HIF-1A, CA9, Bcl2L1 and VEGFA) were randomly selected and performed for qPCR analysis in U87 and U87TR cells. Results showed that the DNMT1, TP53 and Bcl2L1 were significantly upregulated while the HIF-1A, CA9 and VEGFA were downregulated compared to the parental U87 cells (Fig. 5A). With the distinct cellular morphology (Fig. 1) and downregulation of ECM-related pathway (Fig. 4D) in TR cells, we speculated that the ECM-related cellular morphology alterations may associate with the TR properties. In the downregulated ECM-receptor interaction pathway, we found collagen, integrin and laminin expression downregulated with cell-surface glycoprotein CD44 and CD47 (Table VII). Moreover, the ECM related receptor interaction from the KEGG Pathway Database revealed that collagen, fibronectin and laminin could enhance its downstream CD44 expression (Fig. 5B). To verify this, western blot analysis was applied and the results showed the protein expression of collagen I, fibronectin, laminin and CD44 were significantly decreased in U87TR cells as compared to parental U87 cells (Fig. 5C). To comfirm this, ELISA assay was used to analyze the collagen I expression in TMZ treated U87 and U87TR cell supernatants during 3 days. The results showed U87TR cells with significant downregulated collagen I expression when compared to the parental U87 cells during TMZ treatment (Fig. 5D). In addition, the expression of collagen I and CD44 were further confirmed by immunofluorescence staining. Data showed that the U87TR cells presented with relative larger and irregular cytoskeleton (phalloidin in green), decreased secretion of collagen I (Fig. 5E) and weaker CD44 expression (Fig. 5F). Together, these results indicated that the TR phenotype was associated with the downregulation of ECM signaling and ECM-related collagen or CD44 may act as TR phenotype molecular markers.

Figure 5.

ECM-receptor interaction pathway downregulation in GBM TR cells. Microarray profile validation on mRNA expression by qPCR analysis (A), *p<0.05 vs. U87 parental cells. The ECM-receptor interaction pathway from the KEGG database (B). Western blot analysis on ECM-related proteins in U87 and U87TR cells (C). ELISA analysis of collagen I protein expression in TMZ (500 µM) treated U87 and U87TR cell culture supernatants during 3 days, *p<0.05 vs. U87 parental cells (D). The U87 and U87TR cells were plated in 6-well plate overnight and then treated with 500 µM TMZ. After 3-day incubation, immunofluorescence staining was used to analysis collagen I (E) and CD44 (F) expression in U87 and U87TR cells, scale bar, 50 µM..

Discussion

The emergence of acquired drug resistance in tumor constantly leads to chemotherapy faliure or even tumor relapse. Thus, fully understanding its mechanisms is urgent for improving effective chemotherapy and overcoming tumor drug resistance. Here, we sought to explore the mechanisms of acquired resistance to TMZ in GBM through in vitro TMZ-resistant GBM cell lines generated by repetitive exposure to increasing TMZ concentrations. Although this approach may not closely reflect the situation in vivo, it allows us for an assessment of mechanisms triggered by repeated pulse-exposure to TMZ chemotherapy in vitro.

Previous studies have indicated a growing number of molecular mechanisms contributing to TMZ resistance in GBM including genetic and epigenetic, such as MGMT methylation (22), IDH mutations (23), aberrant ABC transporter expression (24,25), p53 mutations and deletions (26), DNA repair deregulation (27,28) and miRNAs (29,30). Furthermore, evidence is now beginning to demonstrate lncRNAs as having important roles in cancer therapy (31,32). However, the relationships between lncRNAs and GBM acquired TMZ resistance are rarely reported. In our study, the TMZ-resistant GBM cell lines were first generated using stepwise selection and then subjected to the Human lncRNA microarray. We found numerous distinctly expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs with up- or downregulation (Tables II and III). To our best knowledge, these results may be the first reporting on expression profile of lncRNAs and mRNAs associated with TMZ resistance in GBM cells in vitro.

For preliminary understanding upon these differential expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs towards TMZ resistance, further functional analysis was processed. In lncRNA classification and subgroup analysis, the lncRNAs were devided into three types, the enhancer-like lncRNAs, lincRNAs and HOX lncRNAs, and each of the function pattern was distinct. For example, lincRNAs regulate the neighboring HOX gene expression via impacting chromatin signature (33) while enhancer-like lncRNAs function by interacting with their nearby coding genes (34). Thus the exact function of lncRNA clusters is not yet clear before every single lncRNA is identified and still need further studies. According to previous studies, we also found some distinct lncRNAs in our study, which are consistent with other researchers, for example, the lncRNA CRNDE (7), UCA-1 (6,35), MEG3 (31,36) and HOTAIR (37). These suggest that the data obtained in this study are reliable. Additionally, lncRNAs were also reported to function in tumor drug resistance through coding transcription modulation (38). In our study, some function of molecules in the drug resistance related MMR and NER signaling pathway were upregulated in U87TR cells, e.g., MSH3 in MMR and ERCC1/2 in NER signaling, which were revealed by the pathway analysis on mRNAs and were consistent with previous reports (39,40).

With the great morphologic changes and downregulation of ECM-receptor interaction pathway in TR cells as compared with their parental cells, we speculate that the cell morphology change may associate with drug resistance phenotype. Previous reports demonstrated that drug resistance acquisition showed statistically significant morphological changes in cell membrane as well as biological parameters (41). Chemotherapy-induced phenotypic reversion of cancer cells is accompanied by regression of several morphological malignant features (42). Here, we have confirmed some important molecules in ECM-receptor interaction pathway, e.g., the collagen, fibronectin, laminin and CD44 were associated with TMZ resistance phenotype. In this study, we showed that the collagen, fibronectin and laminin could enhance its downstream CD44 expression in U87TR cells according to the KEGG pathway database. Chetty et al reported that the CD44-mediated cell matrix interaction in glioma perivascular niches enhances cancer stem cell phenotype and promote tumor aggressiveness (43). Moreover, recent studies have shown that the high level of CD44 was associated with a better survial and better response to radiotherapy and TMZ and the CD44 could establish a prognosis marker by predicting survival and response to therapy for GBM patients (44,45). In our study, the CD44 expression was downregulated in U87TR cells and targeting CD44 expression might enhance the TMZ chemosensitivity to TR cells. However, its role and underlying mechanisms are not fully understood and more effort is still needed for further studies. Therefore, these data suggest that acquired TMZ resistance might be mirrored by the parallel changes in cellular morphology associated with CD44 expression.

In conclusion, we showed differential lncRNAs and mRNAs expression profiles associated with TMZ resistance in GBM cells in vitro, and these dysregulated lncRNAs and mRNAs identified in this work may represent good candidates for future diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers and provide novel targets for overcoming acquired TMZ resistance in GBM chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81672477, 81372691, 81041068 and 30971183) and Guangdong Provincial Clinical Medical Centre for Neurosurgery (no. 2013B020400005). We thank the Department of Anatomy, Key Laboratory of Construction and Detection of Guangdong Province, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, for generous help.

References

- 1.Thomas AA, Brennan CW, DeAngelis LM, Omuro AM. Emerging therapies for glioblastoma. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:1437–1444. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Preusser M, de Ribaupierre S, Wöhrer A, Erridge SC, Hegi M, Weller M, Stupp R. Current concepts and management of glioblastoma. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:9–21. doi: 10.1002/ana.22425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stavrovskaya AA, Shushanov SS, Rybalkina EY. Problems of glioblastoma multiforme drug resistance. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2016;81:91–100. doi: 10.1134/S0006297916020036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarkaria JN, Kitange GJ, James CD, Plummer R, Calvert H, Weller M, Wick W. Mechanisms of chemoresistance to alkylating agents in malignant glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2900–2908. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibb EA, Brown CJ, Lam WL. The functional role of long non-coding RNA in human carcinomas. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:38. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xue M, Chen W, Li X. Urothelial cancer associated 1: A long noncoding RNA with a crucial role in cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142:1407–1419. doi: 10.1007/s00432-015-2042-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Wang Y, Li J, Zhang Y, Yin H, Han B. CRNDE, a long-noncoding RNA, promotes glioma cell growth and invasion through mTOR signaling. Cancer Lett. 2015;367:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ni B, Yu X, Guo X, Fan X, Yang Z, Wu P, Yuan Z, Deng Y, Wang J, Chen D, et al. Increased urothelial cancer associated 1 is associated with tumor proliferation and metastasis and predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol. 2015;47:1329–1338. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang JY, Weng MZ, Song FB, Xu YG, Liu Q, Wu JY, Qin J, Jin T, Xu JM. Long noncoding RNA AFAP1-AS1 indicates a poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma and promotes cell proliferation and invasion via upregulation of the RhoA/Rac2 signaling. Int J Oncol. 2016;48:1590–1598. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun QL, Zhao CP, Wang TY, Hao XB, Wang XY, Zhang X, Li YC. Expression profile analysis of long non-coding RNA associated with vincristine resistance in colon cancer cells by next-generation sequencing. Gene. 2015;572:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.06.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parasramka MA, Maji S, Matsuda A, Yan IK, Patel T. Long non-coding RNAs as novel targets for therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;161:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He DX, Zhang GY, Gu XT, Mao AQ, Lu CX, Jin J, Liu DQ, Ma X. Genome-wide profiling of long non-coding RNA expression patterns in anthracycline-resistant breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2016;49:1695–1703. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan J, Li X, Wu W, Xue M, Hou H, Zhai W, Chen W. Long non-coding RNA UCA1 promotes cisplatin/gemcitabine resistance through CREB modulating miR-196a-5p in bladder cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2016;382:64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li W, Zhai L, Wang H, Liu C, Zhang J, Chen W, Wei Q. Downregulation of LncRNA GAS5 causes trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:27778–27786. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munoz JL, Rodriguez-Cruz V, Greco SJ, Ramkissoon SH, Ligon KL, Rameshwar P. Temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma cells occurs partly through epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated induction of connexin 43. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1145. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munoz JL, Rodriguez-Cruz V, Greco SJ, Nagula V, Scotto KW, Rameshwar P. Temozolomide induces the production of epidermal growth factor to regulate MDR1 expression in glioblastoma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:2399–2411. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munoz JL, Walker ND, Scotto KW, Rameshwar P. Temozolomide competes for P-glycoprotein and contributes to chemoresistance in glioblastoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2015;367:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guil S, Esteller M. RNA-RNA interactions in gene regulation: The coding and noncoding players. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;40:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan Y, Zhang L, Jiang Y, Xu T, Mei Q, Wang H, Qin R, Zou Y, Hu G, Chen J, et al. LncRNA and mRNA interaction study based on transcriptome profiles reveals potential core genes in the pathogenesis of human glioblastoma multiforme. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2015;141:827–838. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1861-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao G, Zhang J, Wang M, Song X, Liu W, Mao C, Lv C. Differential expression of long non-coding RNAs in bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Int J Mol Med. 2013;32:355–364. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan CH, Liu WL, Cao H, Wen C, Chen L, Jiang G. O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase as a promising target for the treatment of temozolomide-resistant gliomas. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e876. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartmann C, Hentschel B, Simon M, Westphal M, Schackert G, Tonn JC, Loeffler M, Reifenberger G, Pietsch T, von Deimling A, et al. German Glioma Network: Long-term survival in primary glioblastoma with versus without isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5146–5157. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaich M, Kestel L, Pfirrmann M, Robel K, Illmer T, Kramer M, Dill C, Ehninger G, Schackert G, Krex D. A MDR1 (ABCB1) gene single nucleotide polymorphism predicts outcome of temozolomide treatment in glioblastoma patients. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:175–181. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin F, de Gooijer MC, Roig EM, Buil LC, Christner SM, Beumer JH, Würdinger T, Beijnen JH, van Tellingen O. ABCB1, ABCG2, and PTEN determine the response of glioblastoma to temozolomide and ABT-888 therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:2703–2713. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang YY, Zhang T, Li SW, Qian TY, Fan X, Peng XX, Ma J, Wang L, Jiang T. Mapping p53 mutations in low-grade glioma: A voxel-based neuroimaging analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:70–76. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner KM, Sun Y, Ji P, Granberg KJ, Bernard B, Hu L, Cogdell DE, Zhou X, Yli-Harja O, Nykter M, et al. Genomically amplified Akt3 activates DNA repair pathway and promotes glioma progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:3421–3426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414573112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trivedi RN, Almeida KH, Fornsaglio JL, Schamus S, Sobol RW. The role of base excision repair in the sensitivity and resistance to temozolomide-mediated cell death. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6394–6400. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong ST, Zhang XQ, Zhuang JT, Chan HL, Li CH, Leung GK. MicroRNA-21 inhibition enhances in vitro chemosensitivity of temozolomide-resistant glioblastoma cells. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:2835–2841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ujifuku K, Mitsutake N, Takakura S, Matsuse M, Saenko V, Suzuki K, Hayashi K, Matsuo T, Kamada K, Nagata I, et al. miR-195, miR-455-3p and miR-10a(*) are implicated in acquired temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma multiforme cells. Cancer Lett. 2010;296:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu J, Wan L, Lu K, Sun M, Pan X, Zhang P, Lu B, Liu G, Wang Z. The long noncoding RNA MEG3 contributes to cisplatin resistance of human lung adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0114586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsang WP, Wong TW, Cheung AH, Co CN, Kwok TT. Induction of drug resistance and transformation in human cancer cells by the noncoding RNA CUDR. RNA. 2007;13:890–898. doi: 10.1261/rna.359007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ulitsky I, Bartel DP. lincRNAs: Genomics, evolution, and mechanisms. Cell. 2013;154:26–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng N, Li X, Zhao C, Ren S, Chen X, Cai W, Zhao M, Zhang Y, Li J, Wang Q, et al. Microarray expression profile of long non-coding RNAs in EGFR-TKIs resistance of human non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep. 2015;33:833–839. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan Y, Shen B, Tan M, Mu X, Qin Y, Zhang F, Liu Y. Long non-coding RNA UCA1 increases chemoresistance of bladder cancer cells by regulating Wnt signaling. FEBS J. 2014;281:1750–1758. doi: 10.1111/febs.12737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J, Bian EB, He XJ, Ma CC, Zong G, Wang HL, Zhao B. Epigenetic repression of long non-coding RNA MEG3 mediated by DNMT1 represses the p53 pathway in gliomas. Int J Oncol. 2016;48:723–733. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Zhang P, Wang L, Piao HL, Ma L. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR in carcinogenesis and metastasis. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2014;46:1–5. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmt117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xia H, Hui KM. Mechanism of cancer drug resistance and the involvement of noncoding RNAs. Curr Med Chem. 2014;21:3029–3041. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666140414101939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Idbaih A, Carvalho Silva R, Crinière E, Marie Y, Carpentier C, Boisselier B, Taillibert S, Rousseau A, Mokhtari K, Ducray F, et al. Genomic changes in progression of low-grade gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2008;90:133–140. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9644-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geng P, Ou J, Li J, Liao Y, Wang N, Xie G, Sa R, Liu C, Xiang L, Liang H. A comprehensive analysis of influence ERCC polymorphisms confer on the development of brain tumors. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:2705–2714. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9371-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pasqualato A, Palombo A, Cucina A, Mariggiò MA, Galli L, Passaro D, Dinicola S, Proietti S, D'Anselmi F, Coluccia P, et al. Quantitative shape analysis of chemoresistant colon cancer cells: Correlation between morphotype and phenotype. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318:835–846. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uppal SO, Li Y, Wendt E, Cayer ML, Barnes J, Conway D, Boudreau N, Heckman CA. Pattern analysis of microtubule-polymerizing and -depolymerizing agent combinations as cancer chemotherapies. Int J Oncol. 2007;31:1281–1291. doi: 10.3892/ijo.31.6.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chetty C, Vanamala SK, Gondi CS, Dinh DH, Gujrati M, Rao JS. MMP-9 induces CD44 cleavage and CD44 mediated cell migration in glioblastoma xenograft cells. Cell Signal. 2012;24:549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 44.Guadagno E, Borrelli G, Califano M, Calì G, Solari D, Del Basso De Caro M. Immunohistochemical expression of stem cell markers CD44 and nestin in glioblastomas: Evaluation of their prognostic significance. Pathol Res Pract. 2016;212:825–832. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pinel B, Duchesne M, Godet J, Milin S, Berger A, Wager M, Karayan-Tapon L. Mesenchymal subtype of glioblastomas with high DNA-PKcs expression is associated with better response to radiotherapy and temozolomide. J Neurooncol. 2017;132:287–294. doi: 10.1007/s11060-016-2367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]