Abstract

Human tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (hTRAIL) has exhibited superior in vitro cytotoxicity in a variety of tumor cells. However, hTRAIL showed a disappointing anticancer effect in clinical trials, although hTRAIL-based regimens were well tolerated. One important reason might be that hTRAIL was largely trapped by its decoy receptors, which are ubiquitously expressed on normal cells. Tumor-targeted delivery might improve the tumor uptake and thus enhance the antitumor effect of hTRAIL. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRβ)-expressing pericytes are enriched in tumor tissues derived both from patients with colon cancer and from mice bearing colorectal tumor xenografts. A ZPDGFRβ affibody showed high affinity (nM) for PDGFRβ and was predominantly distributed on tumor-associated PDGFRβ-positive pericytes. Co-administration with the ZPDGFRβ affibody did not significantly enhance the antitumor effect of hTRAIL in mice bearing tumor xenografts. Fusion to the ZPDGFRβ affibody endows hTRAIL with PDGFRβ-binding ability but does not interfere with its death receptor binding and activation. The fused ZPDGFRβ affibody mediated PDGFRβ-dependent binding of hTRAIL to pericytes. In addition, hTRAIL bound on pericytes could kill tumor cells through juxtatropic activity or exhibit cytotoxicity in tumor cells after being released from pericytes. Intravenously injected hTRAIL fused to ZPDGFRβ affibody initially accumulated on tumor-associated pericytes and then diffused to the tumor parenchyma over time. Fusion to the ZPDGFRβ affibody increased the tumor uptake of hTRAIL, thus enhancing the antitumor effect of hTRAIL in mice bearing tumor xenografts. These results demonstrate that pericyte-targeted delivery mediated by a ZPDGFRβ affibody is an alternative strategy for tumor-targeted delivery of anticancer agents.

Keywords: Pericyte, Platelet-derived growth factor receptor, Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand, Affibody, Drug delivery, Cancer therapy.

Introduction

Apoptosis is a programmed cell death process that eliminates unwanted cells, which is fundamental to tissue hemostasis 1. However, apoptosis is usually disabled in tumor cells, which is essential to the pathogenesis and progression of cancer 2. Consequently, reactivation of the apoptotic signaling pathway in tumor cells might be an efficient approach for cancer therapy 3, 4. Among the apoptotic pathways, the death receptor-mediated pathway has attracted much attention in recent years. One important reason is that the death receptors are usually overexpressed on tumor cells, and thus, their ligands have great potential to be engineered and developed as novel anticancer agents 5.

Of the death receptors, CD95 (Fas), tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 (TNF R1), TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand receptor-1 (TRAIL R1 or DR4) and TRAIL R2 (DR5) were identified as potent mediators of apoptosis 5. Theoretically, their ligands, including Fas ligand (FasL), tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), and TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL), might be developed as pro-apoptotic anticancer drugs. However, it was found that the soluble FasL exhibited poor cytotoxicity 6. In addition, systematic administration of TNFα was limited by its unacceptable toxicity 7. Nevertheless, soluble TRAIL induced apoptosis in tumor cells but spared normal cells, suggesting that selective killing of tumor cells might be achievable with recombinant soluble TRAIL 8.

In fact, recombinant soluble human TRAIL (hTRAIL) exhibited superior cytotoxicity in tumor cells in vitro as well as in animal models 9. Recombinant hTRAIL (Dulanermin, Genentech Inc, CA, USA) was well tolerated as a monotherapy or in combination with other chemicals 10. However, in contrast to the superior cytotoxicity of hTRAIL observed in the in vitro analysis 9, hTRAIL-induced antitumor responses were only observed in a small number of patients 11, 12. On one hand, a short half-life might contribute to the poor clinical efficacy of hTRAIL. PEGylation 13, Fc fusion 14, albumin-fusion 15 and albumin-binding 16 have been used to improve the pharmacodynamics of hTRAIL. On the other hand, decoy receptors 1 and 2 (DcR1 and DcR2), which do not trigger apoptosis upon ligand engagement, are ubiquitously expressed on normal cells 17. Injected hTRAIL might be largely trapped by these receptors, thus reducing its tumor accumulation. Consequently, tumor-targeted delivery of hTRAIL might be more efficient and improve the pharmacokinetics 18.

Tumor tissues consist of tumor cells and stromal cells, such as endothelial cells, pericytes, and fibroblasts 19. Theoretically, all types of cells can be considered target cells for delivery of anticancer agents. In fact, numerous attempts have been made to deliver hTRAIL to tumor cells or tumor-associated fibroblasts by fusion to antibodies against cell surface antigens 20. However, in certain localized tumors, the tumor vasculature established with high pericyte coverage might prevent these fusion proteins from reaching targeted cells that are distant from blood vessels 21. Consequently, it is better to deliver hTRAIL to tumor vasculature, which would facilitate the entry of hTRAIL into the tumor tissues. It is known that the walls of tumor vessels consist of irregularly lined endothelial cells and pericytes covering the endothelial tubule 22, suggesting that both cells might be considered target cells for delivery of anticancer agents. In fact, endothelial cell-targeted delivery mediated by an RGD peptide significantly enhanced the in vivo antitumor effect of hTRAIL 23, suggesting that pericyte-targeted delivery might be another strategy for enhancing the antitumor effect of hTRAIL.

A high-frequency of expression of platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRβ) has been observed on tumor-associated pericytes of different types of tumors 24, suggesting that pericyte-targeted delivery of anticancer agents might be achieved using PDGFRβ-binding molecules. Several PDGFRβ-binding peptides have been identified 25-27, and one of them has been developed as a drug carrier 25. However, these small peptides were limited by their low affinities (~μM level) for PDGFRβ. Affibody is small recognizing molecule developed using Z-domain of Protein A as scaffold. A series of affibody molecules with nM affinity for PDGFRβ have been engineered by Lindborg et al. 28. Radionuclide imaging of mice bearing glioma tumor xenografts demonstrated that one affibody, Z09591, accumulated in tumor xenografts, which quickly triggered our interest in investigating whether these affibodies could be used for pericyte-targeted delivery of hTRAIL.

In this study, we first prepared a derivative of Z09591 affibody, designated ZPDGFRβ affibody, through recombinant expression in E. coli. Subsequently, we examined the PDGFRβ- as well as pericyte-binding ability of the ZPDGFRβ affibody. After verifying the tumor-homing ability, the ZPDGFRβ affibody was fused to the N-terminus of hTRAIL to produce a fusion protein, Z-hTRAIL. Finally, we evaluated the impact of the fused ZPDGFRβ affibody on in vitro cytotoxicity and PDGFRβ- and pericyte-binding ability, as well as the tumor uptake and tumor suppression, of hTRAIL.

Materials and methods

Expression and purification of proteins

The plasmid pQE30-hTRAIL containing the gene encoding hTRAIL (aa 114 to 281, accession number BC032722.1) was used to produce hTRAIL according to our previous work 16. To produce the ZPDGFRβ affibody, the unique C-terminal cysteine residue of Z09591 29 was deleted. An artificial gene encoding the ZPDGFRβ affibody was synthesized by GenScript (Nanjing, China) and cloned into pQE30 to prepare ZPDGFRβ affibody. To produce the fusion protein Z-hTRAIL, the gene encoding the ZPDGFRβ affibody was inserted into pQE30-hTRAIL at the 5'-end of hTRAIL. A flexible linker, (G4S)3, was inserted between the ZPDGFRβ affibody and hTRAIL. In addition, a His-tag in the pQE30 plasmid was replaced by an HE-tag (HEHEHE) 30. To produce recombinant protein, the expression plasmid was transformed into E. coli M15 followed by induction overnight at 26°C (for hTRAIL and Z-hTRAIL) or induction for 4-6 h at 37°C (for ZPDGFRβ affibody) using isopropyl-L-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG, 0.05 mM). The recombinant proteins with an additional HE-tag at the N-terminus were recovered from the supernatant of E. coli cells using Ni-NTA Superflow resin (Qiagen, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Purified hTRAIL and Z-hTRAIL were further identified by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and western blot with an antibody against hTRAIL. The purity of the proteins was also evaluated by size exclusion chromatography. Finally, the purified proteins were dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 137 mM NaCl, 2.68 mM KCl, 2 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) overnight. After determining the concentration using a DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, CA, USA), the proteins were stored at -70°C for further use.

Labeling of Proteins

Labeling of the recombinant proteins with 56-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) or CF750 succinimidyl ester (CF750) (Sigma, CA, USA) was performed according to the description by Wei et al. 31 with some modifications. Briefly, the pH value of the protein solution was adjusted from 7.4 to 8.0 by addition of 1 M NaHCO3. Fluorescent dye dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to the protein solution at a 20:1 (for FAM) or 8:1 (for CF750) molar ratio of dye to protein followed by incubation at room temperature for 1 h in darkness. Subsequently, the mixture was dialyzed against PBS with several buffer changes. The labeling of protein was verified by SDS-PAGE and a fluorospectrophotometer.

Protein-protein interaction

Immunoprecipitation (IP) was used to detect the receptor binding of the recombinant proteins. All procedures were performed at 4°C. The recombinant proteins (Z-hTRAIL or hTRAIL) were pre-incubated with receptor proteins (PDGFRβ-Fc, DR4-Fc, or DR5-Fc, R&D systems, MN) at a molar ratio of 1:1 overnight. At the same time, protein A- and protein G-agarose beads (5 μl of each, GE healthcare, CA) were mixed and blocked with bovine serum albumin (BSA, 5 mg/ml, 50 μl) overnight. Subsequently, protein A/G-agarose beads were added into the protein solution followed by an additional 2 h of incubation. The agarose beads were collected by centrifugation (3000 g, 3 min) and resuspended in 30 μl of SDS-PAGE loading buffer. To extract the adsorbed proteins, the agarose beads were boiled for 20 min. Z-hTRAIL in the extract was measured by western blot with an antibody against hTRAIL.

Biolayer interferometry and surface plasmon resonance were also used for receptor-binding assay. Biolayer interferometry was performed on a BlItz® System (Pall ForteBio LLC, CA) according to the description by Lad et al. 32. Briefly, IgG1 Fc-fusion receptor proteins (PDGFRβ-Fc, DR4-Fc or DR5-Fc) were immobilized on a protein A-coated biosensor. Subsequently, the biosensor tip was dipped into Z-hTRAIL or hTRAIL solutions for association and disassociation assessment. To examine the binding of ZPDGFRβ affibody to PDGFRβ, surface plasmon resonance was performed on an OpenSPR system (Nicoya Lifesciences Inc., Kitchener, Canada) according to the description by Mcgurn et al. 33. The receptor fusion protein PDGFRβ-Fc served as the ligand and was immobilized on COOH-sensor chips. Subsequently, ZPDGFRβ affibody solution was introduced into the sensor chip with PBS as the running buffer. The kinetic constants, including the association constant (ka), dissociation constant (kd) and affinity (KD, KD=kd/ka), were calculated using software according to a 1:1 binding model.

Cell culture

COLO205, LS174T, and HCT116 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, VA, USA) and were cultured in either Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) or RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Human brain vascular pericytes and their specific media were purchased from ScienCell (CA, USA). All cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5 % CO2 humidified atmosphere.

Flow cytometry

Primary antibodies (mouse anti-human PDGFRβ, mouse anti-human DR4, mouse anti-human DR5) and the secondary antibody (anti-mouse IgG1) were purchased from Biolegend (CA, USA). To detect the expression of PDGFRβ, 2×105 cells (in 100 μl of PBS) were incubated with primary antibody against PDGFRβ at 4°C for 1.5 h prior to flow cytometry analysis. To detect the expression of DR4 and DR5, cells were incubated with primary antibody against DR4 or DR5 at 4°C for 1.5 h followed by further incubation with the secondary antibody at 4°C for 45 min. In addition, the cells were washed with PBS at least twice after incubation with each antibody.

To detect the cell binding of recombinant protein, FAM-labeled proteins were incubated with 4×105 cells at 4°C for 1 h. The cells were washed twice with PBS prior to analysis by flow cytometry. To investigate the receptor-dependence of cell binding, Z-hTRAIL was incubated with DR5-Fc or anti-PDGFRβ antibody at 4°C for 1 h prior to addition into the cells. A reduction in the binding rate reflected the role of receptors in cell binding of Z-hTRAIL.

Optical Imaging

LS174T cells (2×106 in 100 μl of PBS) were subcutaneously implanted at the head and neck position of female BALB/C nu/nu mice (4-weeks-old, n=3). Once the volumes of the tumor grafts reached 100-200 mm3, the mice were intravenously injected with CF750-labeled proteins at a single dose of 10 mg/kg hTRAIL or an equal molar amount of Z-hTRAIL or ZPDGFRβ affibody. Subsequently, the mice were scanned at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h post-injection using SPECTRAL Lago and Lago X Imaging Systems (Spectral, AZ, USA). After the last scan, the mice were sacrificed, and the brain, heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, colon, muscle, and tumor were removed and scanned. The fluorescence signal intensities in the tumor and the other organs/tissues were analyzed.

Immunofluorescence histochemistry

The primary antibodies used here included rat anti-mouse CD31 antibody (Biolegend, CA, USA), mouse anti-human CD31 antibody and rabbit anti-human PDGFRβ antibody (Abcam CA, USA). The secondary antibodies were goat anti-rat IgG (DyLight 550), donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibody (DyLight 488 or DyLight 550), and goat anti-mouse IgG (DyLight 550) (Abcam, CA, USA). Tumor tissues derived from patients or mice were frozen, sectioned and fixed with 2 % formaldehyde for 4 min. Subsequently, the tissues were incubated with primary antibody at 37°C for 1.5 h followed by incubation with the corresponding secondary antibody at 37°C for 0.5 h. In addition, the tissues were washed with PBS 4 times prior to incubation with either primary antibody or secondary antibody. The nuclei of cells were visualized using DAPI staining.

To localize the recombinant proteins on PDGFRβ-expressing cells in tumors, FAM-labeled proteins were intravenously injected into mice bearing LS174T tumor xenografts. Subsequently, the tumor xenografts were removed at 5, 30, and 60 min post-injection and frozen and sectioned followed by staining with anti-PDGFRβ antibody or anti-CD31 antibody.

In vitro cytotoxicity assays

To determine the in vitro cytotoxicity, cells (1-2 ×104 cells/well) were inoculated in a 96-well plate and cultured overnight. Proteins at different concentrations were added to the cells followed by incubation overnight. Subsequently, the surviving cells were examined using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Dojindo, Japan) according to the manual provided by the manufacture. The viability of cells treated with PBS was considered 100 %. The protein-mediated decrease in cell viability reflects the cytotoxicity of the protein.

In vivo antitumor effect evaluation

BALB/c nude mice (4 to 6 weeks old, n=6 for each group) were subcutaneously injected with tumor cells (5×105 cells/mouse for COLO205, 2×106 cells/mouse for LS174T and HCT116). Once the tumor grafts were palpable (30-60 mm3), the mice were randomly divided into different groups and were intravenously injected with proteins as a monotherapy or combinational therapy. The mice in the control group were injected with the same volume of PBS. The tumor growth was monitored every day by measuring the longitudinal (L) and transverse (W) diameters of the tumor xenograft. The tumor volume (V) was calculated using the following formula: V=L×W2/2. At the end of experiment, all tumor xenografts were collected, and the tumor masses were measured. To verify the in vivo apoptosis-inducing activity, the mice bearing 200 mm3 tumor xenografts were intravenously injected with a single dose of 10 mg/kg hTRAIL or an equal molar amount of Z-hTRAIL. The tumor xenografts were removed 24 h post-injection and immediately sectioned under frozen conditions. The apoptotic cells in tumor tissues were visualized using a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay (Promega, WI, USA) combined with DAPI staining.

Acute toxicity assays

BALB/c mice (n=7) were intravenously injected with Z-hTRAIL (equivalent of 10 mg/kg of hTRAIL) or hTRAIL (10 mg/kg) every day for 7 days. PBS was used as control. The body weights of mice were recorded every day. One day after the last injection, the mice were sacrificed, and the blood samples were collected to measure the glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (ALT), glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (AST), Serum creatinine (Scr), urea and uric acid (UA). Histological examination of liver and kidney were performed by H&E staining.

Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for multiple comparisons was performed using SPSS software version 13.0. The significance level was defined as p<0.05. The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Results

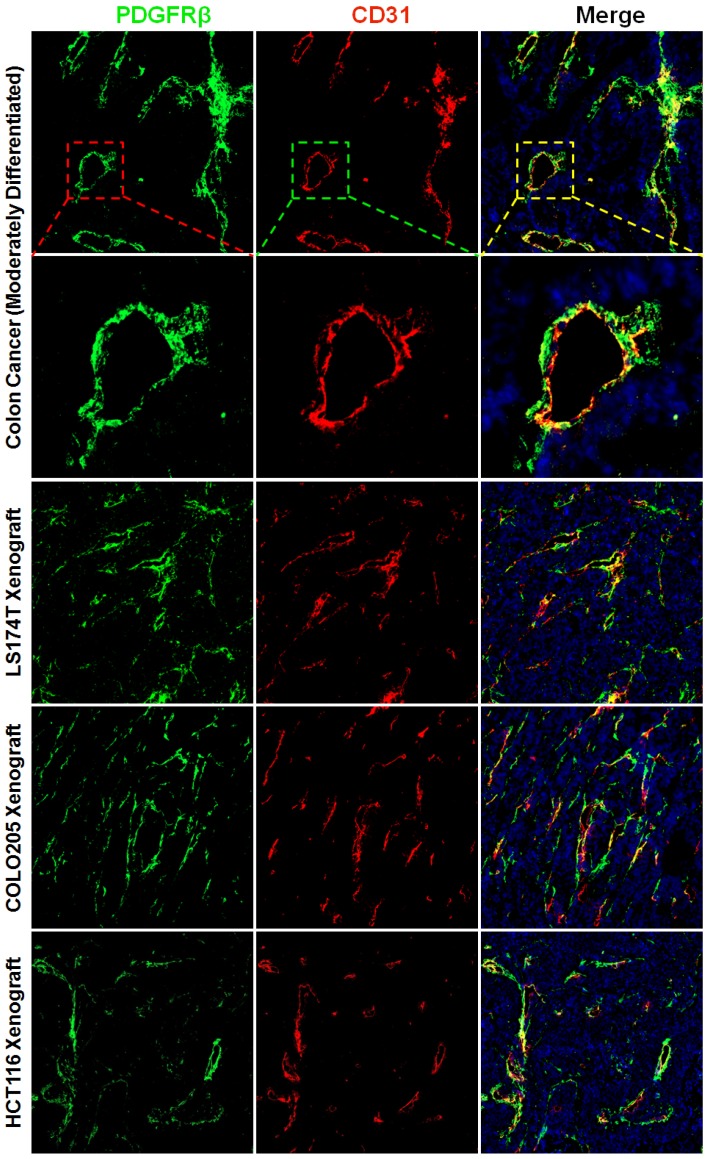

PDGFRβ-positive pericytes and fibroblasts are enriched in tumor tissues derived from patients with colon cancer and mice bearing colorectal tumor xenografts

The wall of blood vessel might be composed of endothelial cells which form the endothelium and mural cells including the pericytes and smooth muscle cells which serve to support and stabilize the endothelium. Pericytes and smooth muscle cells express several biomarkers, but no one is exclusive. Consequently, identification of these cells is dependent on both surface markers and location along the microvessel. PDGFRβ-positive pericytes are located in the blood vessel wall, where these cells are opposed to the endothelium but adjacent to endothelial cells 34. To identify pericytes, the tumor tissues were dual stained with anti-CD31 antibody and anti-PDGFRβ antibody. Fig. 1 and Fig. S1A show that numerous PDGFRβ-positive cells were located at the microvessel walls in tumor tissues derived from patients with colon cancer or derived from mice bearing subcutaneous LS174T, COLO205, or HCT116 colorectal tumor xenografts. Since smooth muscle cells located at blood vessel wall were also PDGFRβ-positive (Fig. S2A), these PDGFRβ-positive cells might not be fully considered as pericytes. But pericytes and smooth muscle cells could be further discerned by surface α-SMA. As shown in Fig. S2A, the expression of α-SMA on vascular smooth muscle cells was significantly higher than that on pericytes. Consequently, in these PDGFRβ-positive cells, α-SMA-positive and α-SMA-negative cells could be considered as smooth muscle cells and pericytes, respectively. As shown in Fig. S2B, few α-SMA-positive cells were observed in tumor microvessels (Fig S2B). Moreover, the number of PDGFRβ-positive cells was significantly greater than that of α-SMA-positive cells, indicating that most PDGFRβ-positive cells in the walls of tumor microvessels were pericytes but not smooth muscle cells. In addition, many cells in the stroma but outside the tumor microvessels were also PDGFRβ-positive (Fig. S1B). These cells were considered fibroblasts. However, no obvious expression of PDGFRβ was observed on tumor cells. These results demonstrated that most PDGFRβ-positive cells in colorectal tumor tissues were pericytes and fibroblasts.

Figure 1.

Expression of PDGFRβ on pericytes in tumor tissues derived from patients with colon cancer or mice bearing colorectal tumor xenografts. Tumor tissues were sectioned under frozen conditions and dually stained with anti-PDGFRβ antibody (green) and anti-CD31 antibody (red). The nuclei of cells were visualized using DAPI (blue). Original magnification, ×200.

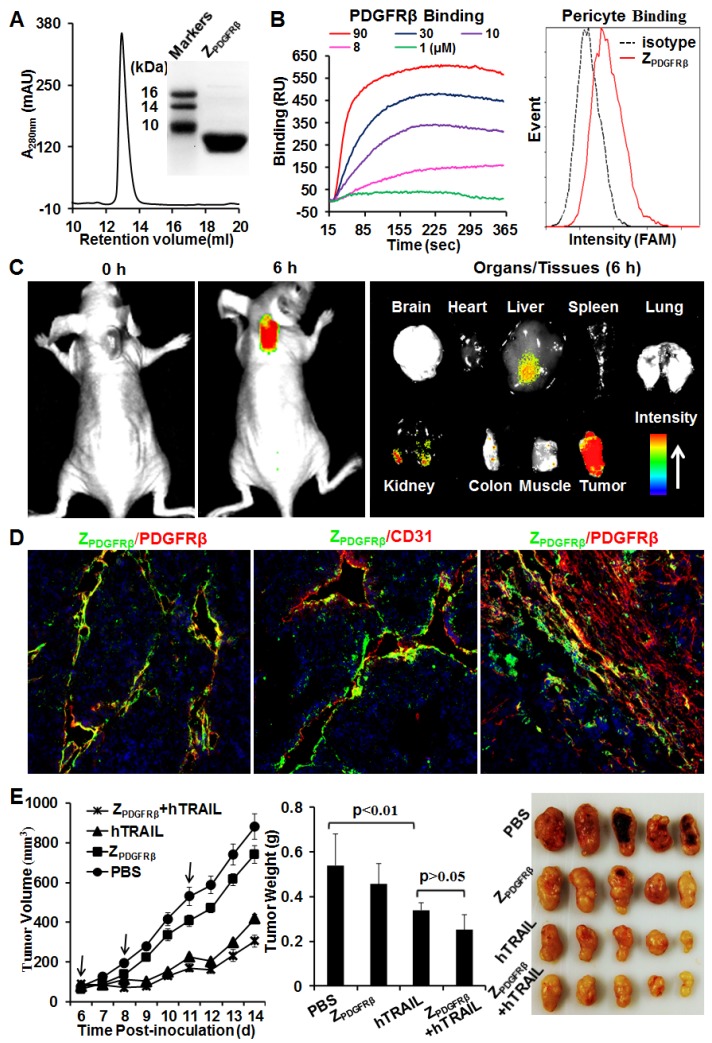

ZPDGFRβ affibody binds to tumor-associated pericytes and thus accumulates in tumor xenografts

ZPDGFRβ affibody was recombinantly expressed in E. coli and purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. As shown in Fig. 2A, the purified ZPDGFRβ affibody was eluted as a single peak in size exclusion chromatography. The apparent molecular weight of the ZPDGFRβ affibody estimated by SDS-PAGE was similar to its theoretical molecular weight of 7.6 kDa. Surface plasmon resonance analysis demonstrated that the ZPDGFRβ affibody could bind the PDGFRβ fusion protein (PDGFRβ-Fc) with a high affinity of 4.5 nM. Moreover, flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that FAM-labeled ZPDGFRβ affibody could bind PDGFRβ-expressing pericytes (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Preparation and characterization of ZPDGFRβ affibody. (A) SDS-PAGE and size exclusion chromatography of purified ZPDGFRβ affibody. (B) Binding of ZPDGFRβ affibody to PDGFRβ-Fc fusion protein and PDGFRβ-expressing pericytes. To measure the binding of ZPDGFRβ affibody to PDGFRβ-Fc using SPR, PDGFRβ-Fc was immobilized on COOH-sensor chips followed by introduction of the ZPDGFRβ affibody (1, 8, 10, 30, or 90 μM) into the sensor chips. Binding of ZPDGFRβ affibody to pericytes was analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) Tumor uptake of ZPDGFRβ affibody illustrated by optical imaging. Mice bearing LS174T tumor grafts were intravenously injected with CF750-labeled ZPDGFRβ affibody followed by dynamic scanning with an optical imaging system. At 6 h post-injection, the organs/tissues were collected and scanned. (D) Co-localization of ZPDGFRβ affibody and PDGFRβ/CD31 in parenchymal and stromal regions of tumor tissues derived from LS174T tumor xenografts. The nuclei of cells were visualized using DAPI (blue). Original magnification, ×200. (E) Evaluation of the antitumor effect of ZPDGFRβ affibody. Mice (n=5) bearing LS174T tumor grafts were intravenously injected with ZPDGFRβ affibody, hTRAIL, or combined ZPDGFRβ affibody and hTRAIL at the indicated time point (arrow). The tumor volumes were measured every day. At the end of the experiment, tumor grafts were collected and weighed.

To investigate the tumor-homing ability of the ZPDGFRβ affibody, mice bearing LS174T tumor xenografts were intravenously injected with CF750-labeled ZPDGFRβ affibody and dynamically scanned using an optical imaging system. Accumulation of ZPDGFRβ affibody in subcutaneous tumor xenografts was detectable at 0.5 h post-injection. Optical images with high contrast were obtained 2 h post-injection. According to the optical images of the organs/tissues obtained 6 h post-injection, intravenously injected ZPDGFRβ affibody was predominately retained in tumor xenografts (Fig. 2C). In addition, the signal of ZPDGFRβ affibody in the tumor xenograft was approximately 2-3 times higher than that in the liver and kidney, indicating that the ZPDGFRβ affibody was tumor-homing. It was found that the ZPDGFRβ affibody was co-localized with PDGFRβ and CD31 in tumor parenchyma (Fig. 2D, Fig. S3A and 3B). However, little accumulation of ZPDGFRβ affibody was observed on PDGFRβ-positive fibroblasts, especially those were distant from tumor microvessels (Fig. 2D and Fig. S3C). These results demonstrated that intravenously injected ZPDGFRβ affibody was distributed on pericytes inside the microvessels but not on fibroblasts outside the microvessels. In addition, these results indicated that binding to tumor-associated pericytes predominantly contributed to the accumulation of ZPDGFRβ affibody in tumor tissues.

Further cytotoxicity assays demonstrated that the ZPDGFRβ affibody was not cytotoxic in LS174T tumor cells and pericytes, even at a high concentration of 10 μM (Fig. S4). Accordingly, ZPDGFRβ affibody (3.2 mg/kg) intravenously injected into mice bearing subcutaneous LS174T tumor xenografts showed little tumor suppression (Fig. 2E). These results suggested that ZPDGFRβ affibody might not be tumor-suppressive as a monotherapy. Due to the superior cytotoxicity in LS174T tumor cells, intravenously injected hTRAIL (10 mg/kg) exhibited an obvious antitumor effect in mice bearing tumor xenografts. However, co-administration with ZPDGFRβ affibody did not significantly enhance the antitumor activity of hTRAIL, suggesting that conjugation to the tumor-homing ZPDGFRβ affibody might be necessary to enhance the antitumor effect of hTRAIL.

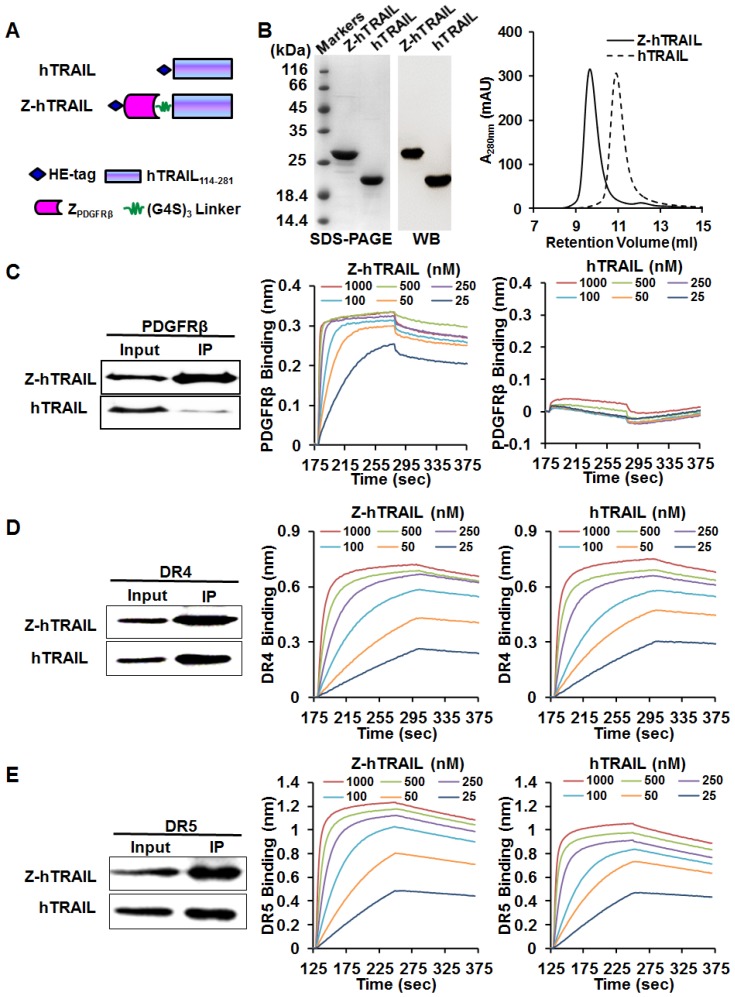

Fusion to ZPDGFRβ endows hTRAIL with PDGFRβ-binding ability

As shown in Fig. 3A, to produce the fusion protein Z-hTRAIL, ZPDGFRβ affibody was genetically fused to the N-terminus of hTRAIL. The gene encoding Z-hTRAIL was inserted into a pQE30 plasmid and inductively expressed in E. coli M15. The recombinant fusion proteins with an N-terminal HE-tag were recovered from the soluble proteins of E. coli using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. As shown in Fig. 3B, the purified Z-hTRAIL was visualized as a single protein band on an SDS-PAGE gel by Coomassie brilliant blue staining, as well as by western blot with an antibody against hTRAIL. Moreover, the purified Z-hTRAIL was eluted as a single peak from the size exclusion chromatography column. These results demonstrated that Z-hTRAIL was purified to homogeneity. Homogenous hTRAIL was also prepared according to the same protocol (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Preparation and receptor-binding of Z-hTRAIL and hTRAIL. (A) Schematic structures of Z-hTRAIL and hTRAIL. (B) SDS-PAGE, western blot, and size exclusion chromatography of purified Z-hTRAIL and hTRAIL. (C), (D), and (E) Binding of Z-hTRAIL or hTRAIL to PDGFRβ-Fc (C), DR4-Fc (D), or DR5-Fc (E) estimated by IP and biolayer interferometry. For IP, the receptor fusion protein (PDGFRβ-Fc, DR4-Fc, or DR5-Fc) was mixed with Z-hTRAIL or hTRAIL first. Subsequently, the protein-receptor complex was pulled down using protein A/G agarose beads and identified by western blot using an antibody against hTRAIL. For biolayer interferometry, the receptor fusion protein was immobilized on a protein A-coated biosensor followed by incubation with Z-hTRAIL or hTRAIL (25, 50, 100, 250, 500, or 1000 nM) for association and disassociation assessment.

To investigate whether fusion to ZPDGFRβ endowed hTRAIL with PDGFRβ-binding ability, the interaction between Z-hTRAIL and PDGFRβ-Fc fusion proteins was first examined using immunoprecipitation (IP). As shown in Fig. 3C, a substantial amount of Z-hTRAIL but not hTRAIL was precipitated by PDGFRβ-Fc, suggesting that Z-hTRAIL might bind PDGFRβ. Biolayer interferometry verified the binding of Z-hTRAIL to PDGFRβ-Fc with a high affinity of 2.31 nM. These results demonstrated that fused ZPDGFRβ affibody contributed to the PDGFRβ-binding of Z-hTRAIL. Moreover, the KD values of Z-hTRAIL for DR4-Fc (5.8 nM) and DR5-Fc (4.2 nM) were comparable to those of hTRAIL for DR4-Fc (3.8 nM) and DR5-Fc (4.5 nM). These results demonstrated that the fused ZPDGFRβ affibody endowed hTRAIL with PDGFRβ-binding ability but did not reduce its death receptor-binding ability.

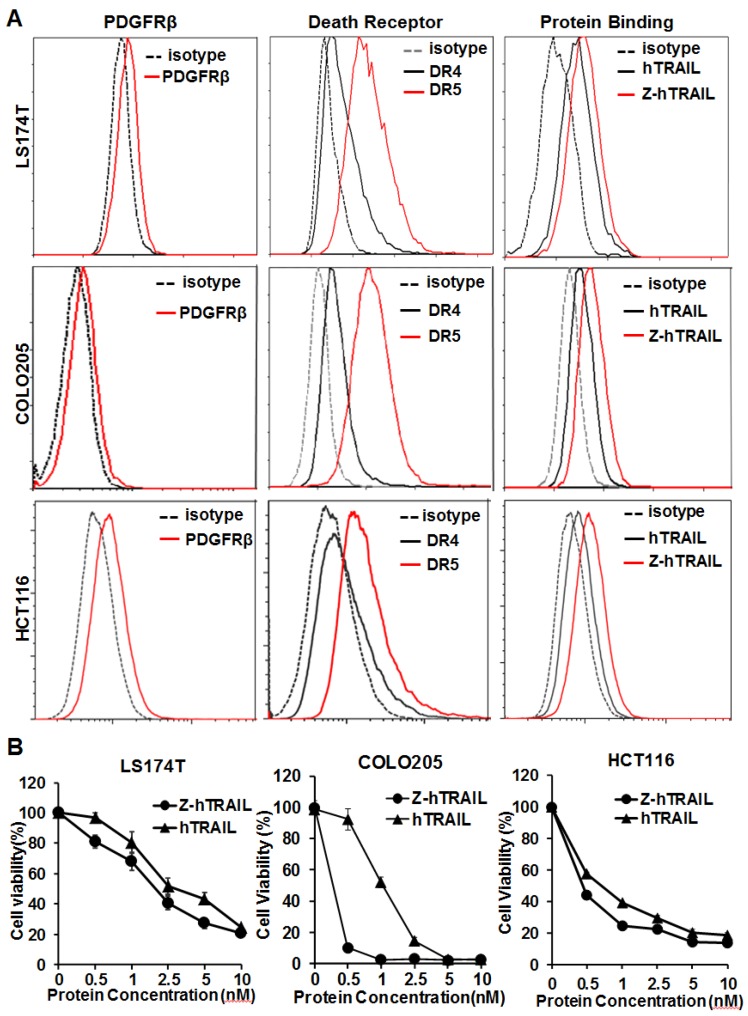

Fusion to ZPDGFRβ mediates pericyte-targeted delivery of hTRAIL

In the three colorectal cell lines (LS174T, COLO205, and HCT116) tested, flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that approximately 25-40 % of the cells were DR4-positive, and over 80 % of the cells were DR5-positive. These cells also expressed PDGFRβ, but the expression level was low (~10 % positive rate) (Fig. 4A). In fact, the binding of hTRAIL and Z-hTRAIL to COLO205 cells was almost blocked by preincubation of the proteins with DR5-Fc (Fig. S5A), indicating that binding of Z-hTRAIL and hTRAIL to COLO205 cells predominantly relied on death receptors. Owing to the low expression of PDGFRβ on tumor cells, the binding and cytotoxicity of Z-hTRAIL to the three tumor cell lines was stronger, but not significantly stronger, than that of hTRAIL (Fig. 4B). In addition, both Z-hTRAIL and hTRAIL induced caspase-dependent apoptosis in tumor cells (Fig. S6). These results demonstrated that fusion to ZPDGFRβ affibody did not interfere with the biological activity of hTRAIL in tumor cells.

Figure 4.

Cytotoxicity of Z-hTRAIL and hTRAIL in colorectal tumor cells. (A) Receptor expression (PDGFRβ, DR4, and DR5) and protein binding of LS174T, COLO205, and HCT116 tumor cells. To detect the receptor, cells were incubated with antibody against PDGFRβ, DR4, or DR5 followed by flow cytometry. To examine the protein binding, cells were incubated with FAM-labeled Z-hTRAIL or hTRAIL prior to flow cytometry. (B) Cytotoxicity of Z-hTRAIL and hTRAIL. Cells (1-2×104 cells/well) were incubated with different concentration of Z-hTRAIL or hTRAIL overnight. PBS was used as the control. The surviving cells were measured using CCK-8.

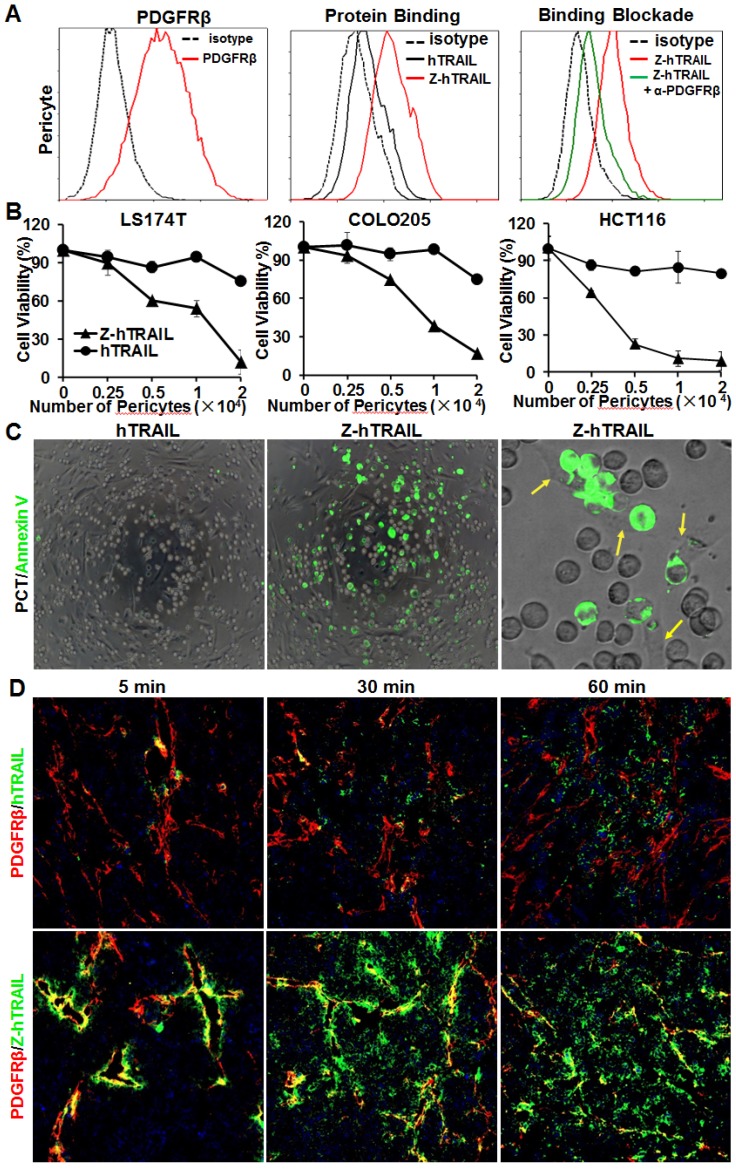

Unlike the above tumor cells, pericytes expressed high levels (77.2 % positive rate) of PDGFRβ (Fig. 5A) and low levels (<10 % positive rate) of DR4 and DR5 (Fig. S5B). Consequently, the binding rate of Z-hTRAIL to pericytes (76.1 %) was much higher than that (20.5 %) of hTRAIL. Moreover, the binding rate of Z-hTRAIL to pericytes was reduced from approximately 73.5 % to 20.2 % by preincubation of pericytes with anti-PDGFRβ antibody (Fig. 5A). However, preincubation of Z-hTRAIL with DR5-Fc fusion protein only reduced the binding rates of Z-hTRAIL for pericytes from 76.7 % to 53.7 % (Fig. S5B). These results demonstrated that pericyte-binding of Z-hTRAIL predominantly relied on PDGFRβ but not on death receptors. However, the binding of hTRAIL to pericytes was completely inhibited by preincubation of hTRAIL with DR5-Fc protein but not by preincubation with antibody against PDGFRβ (Fig. S5C). Moreover, due to the low expression of death receptors (Fig. S5B) and high expression of decoy receptors for hTRAIL (Fig. S5D), pericytes were resistant to hTRAIL as well as Z-hTRAIL (Fig. S5E). These results indicated that fusion to the ZPDGFRβ affibody increased the PDGFRβ-dependent binding but not the cytotoxicity of hTRAIL to pericytes.

Figure 5.

ZPDGFRβ affibody-mediated binding of hTRAIL to pericytes. (A) Binding of Z-hTRAIL and hTRAIL to pericytes. For the protein binding assay, cells were incubated with FAM-labeled proteins followed by flow cytometry. To determine the PDGFRβ-dependent binding, cells were preincubated with anti-PDGFRβ antibody prior to incubation with Z-hTRAIL. (B) Cytotoxicity of Z-hTRAIL bound to pericytes in colorectal tumor cells. Pericytes were first incubated with Z-hTRAIL or hTRAIL. After being washed with PBS, different amounts of pericytes were mixed to a constant number of tumor cells (1.5×104 cells for LS174T and HCT116 or 2×104 cells for COLO205) and further incubated overnight. The surviving cells were measured using CCK8. Pericytes that were not preincubated with proteins were used as controls. The survival rates of tumor cells mixed with pericytes preincubated without proteins were considered 100 %. (C) Apoptosis of tumor cells co-cultured with pericytes loaded with Z-hTRAIL or hTRAIL. Apoptotic cells were visualized by Annexin V staining. Pericytes attached to the apoptotic cells (green) are indicated by arrows. (D) Dynamic distribution of Z-hTRAIL in LS174T tumor xenografts. Mice bearing tumor grafts were intravenously injected with FAM-labeled Z-hTRAIL or an equal molar amount of hTRAIL (green). At 5, 30, and 60 min post-injection, the tumor grafts were collected and sectioned under frozen conditions. Subsequently, the slides were stained with anti-PDGFRβ antibody (red). The nuclei of cells were visualized using DAPI (blue). Original magnification, ×200.

The efficiency of Z-hTRAIL and hTRAIL in killing tumor cells was similar (Fig. 4B). However, co-culture with pericytes preincubated with Z-hTRAIL, but not hTRAIL, induced great apoptosis in tumor cells (Fig. 5B and 5C), suggesting that the amount of Z-hTRAIL bound to pericytes was more than that of hTRAIL bound to pericytes. Typically, apoptosis was observed in tumor cells attached to pericytes within the first several hours of co-culture (Fig. 5C), indicating that Z-hTRAIL could kill bystander tumor cells through juxtatropic action. With increased co-culture time, an increasing number of tumor cells, including those that were distant from pericytes, were killed, demonstrating that Z-hTRAIL could be released from pericytes and exert cytotoxic effects. To monitor the dynamic distribution of protein in tumor xenografts, FAM-labeled Z-hTRAIL was intravenously injected into mice bearing subcutaneous LS174T tumor grafts. As shown in Fig. 5D, 5 min post-injection, the distribution of Z-hTRAIL was limited to the PDGFRβ-positive pericytes in microvessel walls. At 30 and 60 min post-injection, Z-hTRAIL was observed not only on pericytes but also on tumor cells far from microvessels. However, little distribution of Z-hTRAIL was observed on fibroblasts, especially those that were distant from microvessels (data not shown). These results indicated that intravenously injected Z-hTRAIL predominantly accumulated on PDGFRβ-positive pericytes initially and then diffused to neighboring tumor cells. However, the distribution of hTRAIL was not closely related to PDGFRβ-positive pericytes, indicating that the fused ZPDGFRβ affibody contributed to the pericyte-targeted delivery of hTRAIL.

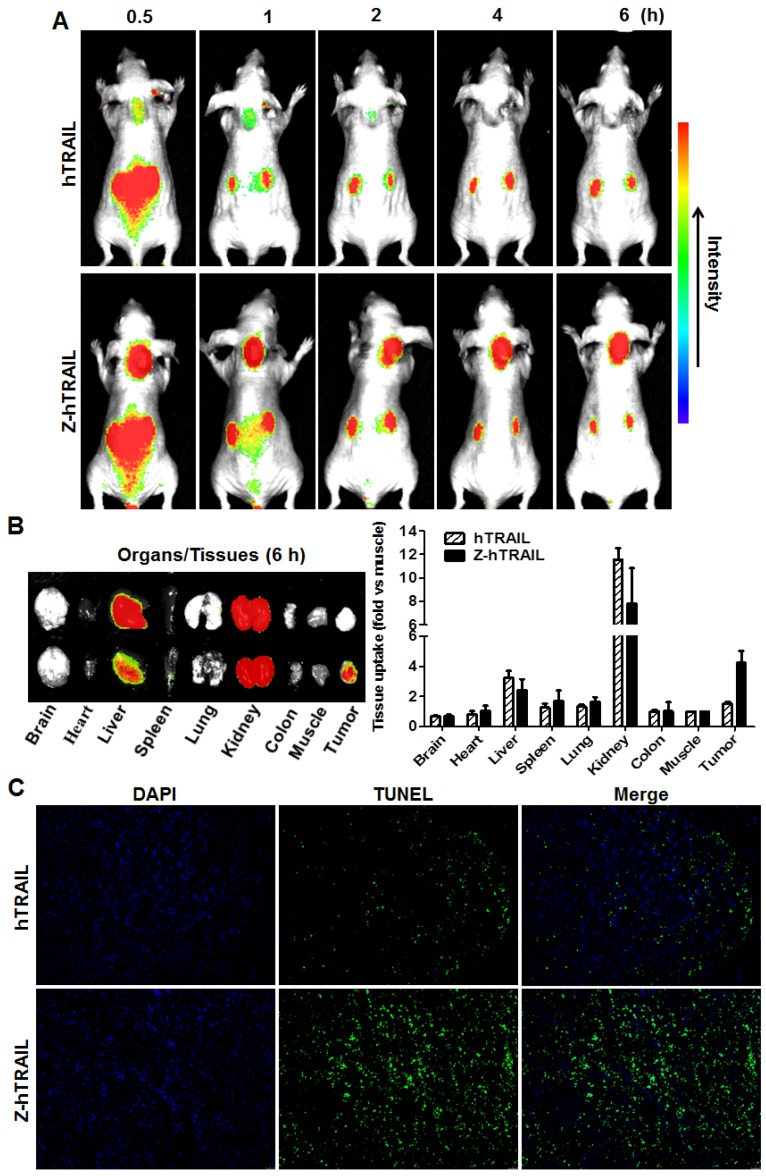

Fusion to ZPDGFRβ increases the tumor uptake of hTRAIL

To monitor the dynamic tumor uptake of proteins, mice bearing LS174T tumor xenografts were intravenously injected with CF750-labeled hTRAIL or an equal molar amount of Z-hTRAIL and then scanned using an optical imaging system at different post-injection times. As shown in Fig. 6A, uptake of hTRAIL and Z-hTRAIL by tumor grafts was detectable at 0.5 h post-injection. However, the Z-hTRAIL signal was much stronger than that of hTRAIL. The hTRAIL signal was drastically reduced 1 h post-injection, whereas the signal of Z-hTRAIL persisted for at least 6 h. These results demonstrated that the tumor uptake of Z-hTRAIL was greater than that of hTRAIL. The difference between hTRAIL and Z-hTRAIL in tumor uptake was further verified by optical imaging of tumor tissues collected 6 h post-injection. As shown in Fig. 6B, the average tumor uptake of Z-hTRAIL was approximately 3-4 times higher than that of hTRAIL. Accordingly, as shown in Fig. 6C, the number of apoptotic cells in tumor xenografts treated with Z-hTRAIL was higher than that in tumor grafts treated with hTRAIL. These results demonstrated that fused ZPDGFRβ affibody increased the tumor uptake of hTRAIL.

Figure 6.

Comparison of tumor uptake of Z-hTRAIL and hTRAIL. (A) Uptake of Z-hTRAIL or hTRAIL by subcutaneous tumor grafts. Mice bearing LS174T tumor xenografts were intravenously injected with CF750-labeled Z-hTRAIL or an equal molar amount of hTRAIL followed by dynamic scanning with an optical imaging system. (B) Biodistribution of Z-hTRAIL and hTRAIL in organs/tissues. At 6 h post-injection, the mice were sacrificed, and the organs/tissues were collected and scanned. (C) Apoptosis induction mediated by Z-hTRAIL and hTRAIL. Mice bearing LS174T tumor xenografts were intravenously injected with Z-hTRAIL or an equal molar amount of hTRAIL. After 24 h, the tumor grafts were removed and sectioned under frozen conditions. The apoptotic cells were visualized using TUNEL staining (green). The nuclei of cells were visualized using DAPI (blue). Original magnification, ×200.

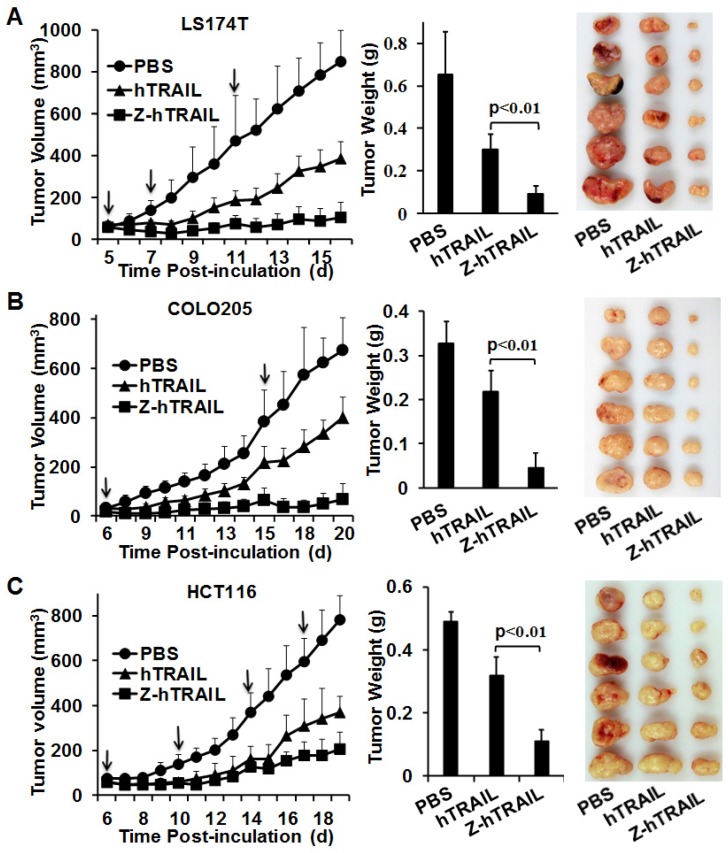

Fusion to ZPDGFRβ enhances the antitumor effects of hTRAIL in mice bearing tumor xenografts

The in vivo antitumor effect of hTRAIL and Z-hTRAIL was compared in mice bearing LS174T, COLO205, or HCT116 tumor xenografts. Tumor cells were subcutaneously injected into mice. As shown in Fig. 7A, compared to hTRAIL, Z-hTRAIL showed greater tumor suppression in mice bearing LS174T tumor xenografts. At the end of this experiment, the average tumor weights of PBS-, hTRAIL-, and Z-hTRAIL-treated mice were 0.652±0.2 g, 0.302±0.068 g, and 0.091±0.039 g, respectively. The difference between the average tumor weights of Z-hTRAIL- and hTRAIL-treated mice was significant (p<0.01). Similarly, the antitumor activity of Z-hTRAIL in mice bearing COLO205 (Fig. 7B) or HCT116 (Fig. 7C) subcutaneous tumor xenografts was also significantly (p<0.01) stronger than that of hTRAIL. Specifically, the average weight of tumors from Z-hTRAIL-treated mice bearing COLO205 tumor xenografts was 0.038±0.035 g, compared to 0.23±0.053 g for the hTRAIL group and 0.27±0.11 g for the PBS group. In mice bearing HCT116 tumor xenografts, the average weight of tumors in the Z-hTRAIL group was 0.11±0.036 g, which was significantly less than that of 0.319±0.06 g for the hTRAIL group and 0.491±0.032 g for the PBS group. These results demonstrated that fusion to ZPDGFRβ affibody enhanced the antitumor effect of hTRAIL.

Figure 7.

Tumor suppression mediated by Z-hTRAIL or hTRAIL in mice bearing LS174T (A), COLO205 (B), or HCT116 (C) tumor xenografts. Mice bearing tumor grafts were intravenously injected with 10 mg/kg hTRAIL or an equal molar amount of Z-hTRAIL (indicated by an arrow). Mice in the control group were injected with the same volume of PBS. Tumor growth was monitored by measuring the tumor volume every day. At the end of the experiment, all tumor grafts were removed and weighed.

Fusion to ZPDGFRβ did not increase the acute liver and kidney toxicity of hTRAIL

To evaluate the short term acute liver and kidney toxicity, mice were intravenously injected with Z-hTRAIL or hTRAIL daily for 7 days. During the period of this experiment, the body weights of mice treated with Z-hTRAIL, hTRAIL, or PBS increased along time (Fig. S7A). Moreover, the blood biochemical indicators for function of liver (ALT and AST) and kidney (Src, Urea and UA) of mice in three groups were similar (Fig. S7B). In addition, histological examination by H&E staining did not show obvious abnormal structure in liver and kidney of mice treated with Z-hTRAIL and hTRAIL (Fig. S7C). These results demonstrated that Z-hTRAIL and hTRAIL had no obvious acute liver and kidney toxicity.

Discussion

Tumor blood vessels are highly disorganized, irregularly shaped and excessively branched. These abnormalities in structure contribute to the high interstitial fluid pressure that compromises blood flow and thus interferes with extravasation of tumor cell-targeted agents and delivery to the tumor parenchyma 35, 36. Consequently, tumor vasculature-targeted delivery of anticancer agents might be more efficient than tumor cell-targeted delivery. Endothelial cells and pericytes are the major cellular components of tumor microvessels. Endothelial cells comprise the endothelium of microvessels, whereas pericytes encompass the endothelial tubule. Definitely, endothelial cells are ideal target cells for vasculature-based drug delivery. It appears to be pericyte-targeted delivery would be hampered by the normal endothelial cell barrier. However, the endothelium of tumor microvessels is usually incomplete (characterized by discontinuities or gaps) and thus lacks the barrier function of normal blood vessels 37. In addition, most pericytes on tumor vessels are loosely attached to endothelial cells, and their aberrant cytoplasmic projections can invade the tumor parenchyma 38, suggesting that tumor-associated pericytes might be considered additional target cells for drug delivery.

PDGFRβ is abundantly expressed on tumor-associated pericytes. Therefore, PDGFRβ-binding molecules could be used for pericyte-targeted delivery. In previous studies, several PDGFRβ-binding peptides have been identified 25-27. However, these peptides showed low affinity (μM) for PDGFRβ. Affibodies are a new class of affinity ligands, screened by phage display from a library based on the 58 amino acid Z-domain of the IgG-binding region of staphylococcal protein A 39. Affibodies are similar to antibodies in affinity and specificity. However, affibodies have advantages of a small size, high stability, an absence of cysteines, and high yield bacterial expression, which has elicited great interest in the application of affibodies as drug carriers. Lindborg et al. identified various affibodies against PDGFRβ 28. Of these affibodies, Z02465 showed nM affinity for human and murine PDGFRβ, but did not bind to PDGFRα, indicating a high specificity for PDGFRβ. To reduce the liver accumulation, affibody Z09591, which differed from Z02465 at two positions, was produced 29. In addition, U87 tumor xenografts in mice were clearly visualized by intravenously injected radionuclide-labeled Z09591. These results demonstrated that this PDGFRβ-specific affibody was tumor-homing, which elicited our interest in using this affibody for hTRAIL delivery.

In this experiment, we prepared the ZPDGFRβ affibody (Z09591 without the C-terminal cysteine), through recombinant expression in E. coli. The affinity of the purified ZPDGFRβ affibody for human PDGFRβ-Fc protein was approximately 4-5 nM (Fig. 2B), which was comparable to that of the parent affibody Z02465 28. Similar to the observation by Tolmachev et al. 29 in mice bearing U87 tumor xenografts, dynamic optical imaging in the current experiment also revealed the accumulation of CF750-labeled ZPDGFRβ affibody in LS174T tumor xenografts (Fig. 2C). These results demonstrated that the ZPDGFRβ affibody was tumor-homing, suggesting that tumor-targeted delivery of hTRAIL might be achieved by fusion to the ZPDGFRβ affibody. Previous studies demonstrated that fusion at the N-terminus has less influence on the biological activity of hTRAIL 16,40. Therefore, we produced Z-hTRAIL by fusing the ZPDGFRβ affibody to the N-terminus of hTRAIL. As expected, Z-hTRAIL, but not hTRAIL showed nM affinity for PDGFRβ-Fc (Fig. 3C). Moreover, the affinity of Z-hTRAIL for DR4/DR5 was similar to that of hTRAIL. These results demonstrated that the fused ZPDGFRβ affibody endowed hTRAIL with PDGFRβ-binding ability but did not interfere with its death receptor-binding ability.

A flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that PDGFRβ was expressed on the tested colorectal tumor cells at a low level (~ 10 % positive rate). Thus, fusion to ZPDGFRβ affibody did not significantly increase the cell binding (Fig. 4A) or the cytotoxicity (Fig. 4B) of hTRAIL in these tumor cells. However, over 70 % of the pericytes were PDGFRβ-positive. Consequently, fusion with the ZPDGFRβ affibody significantly increased the binding of hTRAIL to pericytes (Fig. 5A). Pericytes loaded with Z-hTRAIL showed cytotoxicity in co-cultured tumor cells (Fig. 5B), suggesting that Z-hTRAIL bound to pericytes could kill bystander tumor cells or that Z-hTRAIL could be released from pericytes and exhibit cytotoxicity. In fact, Z-hTRAIL bound to pericytes killed tumor cells attached to pericytes for the first several hours of co-culture (Fig. 5C), indicating a juxtatropic action of Z-hTRAIL. As the co-culture time increased, apoptosis was also observed in tumor cells that were not attached to pericytes, demonstrating that Z-hTRAIL could be released from pericytes and produce cytotoxic effects. It was found that the distribution of Z-hTRAIL was limited on PDGFRβ-positive pericytes in LS174T tumor xenografts 5 min post-injection. However, at 30 and 60 min post-injection, distribution of Z-hTRAIL was extended to PDGFRβ-negative tumor cells far from the microvessels (Fig. 5D), which verified the release of Z-hTRAIL from pericytes. Unlike Z-hTRAIL, intravenously injected ZPDGFRβ affibody was trapped by pericytes in tumors even at 2 h post-injection (Fig. 2D). Because LS174T tumor cells express PDGFRβ at a low level, the high affinity of hTRAIL for death receptor overexpressed on tumor cells might contribute to the transfer of Z-hTRAIL from pericytes to neighboring tumor cells. Interestingly, although fibroblasts also express PDGFRβ (Fig. S1B), little ZPDGFRβ affibody (Fig. 2D and S2C) or Z-hTRAIL was distributed on fibroblasts, especially those that were distant from tumor microvessels, suggesting that the delivery of hTRAIL to fibroblasts was hampered by the endothelial cell and pericyte barrier.

As expected, fusion to the ZPDGFRβ affibody increased the tumor uptake of hTRAIL (Fig. 6A, B). Although no obvious synergism was observed between the ZPDGFRβ affibody and hTRAIL in tumor suppression (Fig. 2E), fusion to the ZPDGFRβ affibody markedly enhanced the antitumor effect of hTRAIL in mice bearing colorectal tumor xenografts (Fig. 7), suggesting that Z-hTRAIL might be developed as a novel anticancer agent. However, application of Z-hTRAIL may be limited to hTRAIL-sensitive tumors with high coverage of pericytes. In hTRAIL-sensitive tumors with low pericyte coverage, Z-hTRAIL might be used in combination with agents that restrict vascular sprouting and tumor angiogenesis that would increase pericyte coverage 21. Unlike tumor cell-targeted delivering systems, ZPDGFRβ affibody-mediated pericyte-targeted drug delivery may not be hampered by an endothelial cell barrier in tumor microvessels. Moreover, since pericytes are common cellular components of tumor microvessels, a ZPDGFRβ affibody-based system might be developed as a universal delivery system for cancer therapy.

Conclusions

Due to the high affinity for PDGFRβ, the ZPDGFRβ affibody predominantly distributes on PDGFRβ-positive tumor-associated pericytes and thus accumulates in tumor xenografts. Fusion to the ZPDGFRβ affibody at the N-terminus endows hTRAIL with PDGFRβ as well as pericyte-binding ability but does not reduce its cytotoxicity in tumor cells. Fusion with ZPDGFRβ affibody mediates pericyte-targeted delivery and thus increases the tumor uptake and enhances the antitumor effect of hTRAIL. A ZPDGFRβ affibody-based delivery system could be used for targeted therapy of tumors, especially those with high pericyte coverage.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81273419 and 81573336) and the National Key Clinical Program. The authors thank Yi Zhang, Yan Liang (from the Experimental Histopathology Platform of West China Hospital), Zongze Yang and Weiwei Tan (from the Tissues Bank of West China Hospital) for their help in collecting and sectioning tumor tissues.

Ethical approval

All applicable institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals and the collection of tumor tissues from patients were followed.

References

- 1.Bright J, Khar A. Apoptosis: programmed cell death in health and disease. Biosci Rep. 1994;14:67–81. doi: 10.1007/BF01210302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowa SW, Lin AW. Apoptosis in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:489–95. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fesik SW. Promoting apoptosis as a strategy for cancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:876–85. doi: 10.1038/nrc1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong RS. Apoptosis in cancer-from pathogenesis to treatment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2011;30:87. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-30-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wajant H, Gerspach J, Pfizenmaier K. Engineering death receptor ligands for cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2013;332:163–74. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O' Reilly LA, Tai L, Lee L, Kruse EA, Grabow S, Fairlie WD, Haynes NM, Tarlinton DM, Zhang JG, Belz GT, Smyth MJ, Bouillet P, Robb L, Strasser A. Membrane-bound Fas ligand only is essential for Fas-induced apoptosis. Nature. 2009;461:659–63. doi: 10.1038/nature08402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerspach J, Pfizenmaier K, Wajant H. Improving TNF as a cancer therapeutic: tailor-made TNF fusion proteins with conserved antitumor activity and reduced systemic side effects. BioFactors. 2009;35:364–72. doi: 10.1002/biof.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holland PM. Targeting Apo2L/TRAIL receptors by soluble Apo2L/TRAIL. Cancer Lett. 2013;332:156–62. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stuckey DW, Shah K. TRAIL on trial: preclinical advances in cancer therapy. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19:685–94. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fulda S. Safety and tolerability of TRAIL receptor agonists in cancer treatment. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71:525–7. doi: 10.1007/s00228-015-1823-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herbst RS, Eckhardt SG, Kurzrock R, Ebbinghaus S, O'Dwyer PJ, Gordon MS, Novotny W, Goldwasser MA, Tohnya TM, Lum BL, Ashkenazi A, Jubb AM, Mendelson DS. Phase I dose-escalation study of recombinant human Apo2L/TRAIL, a dual proapoptotic receptor agonist, in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2839–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wainberg ZA, Messersmith WA, Peddi PF, Kapp AV, Ashkenazi A, Royer-Joo S, Portera CC, Kozloff MF. A phase 1B study of dulanermin in combination with modified FOLFOX6 plus bevacizumab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2013;12:248–54. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim TH, Youn YS, Jiang HH, Lee S, Chen X, Lee KC. PEGylated TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) analogues: pharmacokinetics and antitumor effects. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22:1631–7. doi: 10.1021/bc200187k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang H, Davis JS, Wu X. Immunoglobulin Fc domain fusion to TRAIL significantly prolongs its plasma half-life and enhances its antitumor activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:643–50. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chae SY, Kim TH, Park K, Jin CH, Son S, Lee S, Youn YS, Kim K, Jo DG, Kwon IC, Chen X, Lee KC. Improved antitumor activity and tumor targeting of NH(2)-terminal-specific PEGylated tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1719–29. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li R, Yang H, Jia D, Nie Q, Cai H, Fan Q, Wan L, Li L, Lu XF. Fusion to an albumin-binding domain with a high affinity for albumin extends the circulatory half-life and enhances the in vivo antitumor effects of human TRAIL. J Control Release. 2016;228:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LeBlanc HN, Ashkenazi A. Apo2L/TRAIL and its death and decoy receptors. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:66–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erkoc P, Cingoz A, Onder TB, Kizilel S. Quinacrine Mediated Sensitization of Glioblastoma (GBM) Cells to TRAIL through MMP-Sensitive PEG Hydrogel Carriers. Macromol Biosci; 2017. p. 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, Liu J. Tumor stroma as targets for cancer therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;137:200–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Bruyn M, Bremer E, Helfrich W. Antibody-based fusion proteins to target death receptors in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013;332:175–83. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng MB, Zaorsky NG, Deng L, Wang HH, Chao J, Zhao LJ, Yuan ZY, Ping W. Pericytes: a double-edged sword in cancer therapy. Future Oncol. 2015;11:169–79. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang WG, Andrejecsk JW, Kluger MS, Saltzman WM, Pober JS. Pericytes modulate endothelial sprouting. Cardiovascular research. 2013;100:492–500. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao L, Du P, Jiang SH, Jin GH, Huang QL, Hua ZC. Enhancement of antitumor properties of TRAIL by targeted delivery to the tumor neovasculature. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:851–61. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paulsson J, Sjöblom T, Micke P, Pontén F, Landberg G, Heldin CH, Bergh J, Brennan DJ, Jirström K, Ostman A. Prognostic significance of stromal platelet-derived growth factor beta-receptor expression in human breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:334–41. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prakash J, de Jong E, Post E, Gouw AS, Beljaars L, Poelstra K. A novel approach to deliver anticancer drugs to key cell types in tumors using a PDGF receptor-binding cyclic peptide containing carrier. J Control Release. 2010;145:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Askoxylakis V, Marr A, Altmann A, Markert A, Mier W, Debus J, Huber PE, Haberkorn U. Peptide-based targeting of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta. Mol Imaging Biol. 2013;15:212–21. doi: 10.1007/s11307-012-0578-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marr A, Nissen F, Maisch D, Altmann A, Rana S, Debus J, Huber PE, Haberkorn U, Askoxylakis V. Peptide arrays for development of PDGFRbeta Affine molecules. Mol Imaging Biol. 2013;15:391–400. doi: 10.1007/s11307-013-0616-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindborg M, Cortez E, Höidén-Guthenberg I, Gunneriusson E, von Hage E, Syud F, Morrison M, Abrahmsén L, Herne N, Pietras K, Frejd FY. Engineered high-affinity affibody molecules targeting platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta in vivo. J Mol Biol. 2011;407:298–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tolmachev V, Varasteh Z, Honarvar H, Hosseinimehr SJ, Eriksson O, Jonasson P, Frejd FY, Abrahmsen L, Orlova A. Imaging of platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta expression in glioblastoma xenografts using affibody molecule 111In-DOTA-Z09591. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:294–300. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.121814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tolmachev V, Hofström C, Malmberg J, Ahlgren S, Hosseinimehr SJ, Sandström M, Abrahmsén L, Orlova A, Gräslund T V. HEHEHE-tagged affibody molecule may be purified by IMAC, is conveniently labeled with [⁹⁹(m)Tc(CO)₃](+), and shows improved biodistribution with reduced hepatic radioactivity accumulation. Bioconjug Chem. 2010;17:2013–22. doi: 10.1021/bc1002357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei D, Fan Q, Cai H, Yang H, Wan L, Li L, Lu X. CF750-A33scFv-Fc-based optical imaging of subcutaneous and orthotopic xenografts of GPA33-positive colorectal cancer in mice. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:505183. doi: 10.1155/2015/505183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lad L, Clancy S, Kovalenko M, Liu C, Hui T, Smith V, Pagratis N. High-throughput kinetic screening of hybridomas to identify high-affinity antibodies using bio-layer interferometry. J Biomol Screen. 2015;20:498–507. doi: 10.1177/1087057114560123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGurn LD, Moazami-Goudarzi M, White SA, Suwal T, Brar B, Tang JQ, Espie GS, Kimber MS. The structure, kinetics and interactions of the beta-carboxysomal beta-carbonic anhydrase, CcaA. Biochem J. 2016;473:4559–72. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geevarghese A, Herman IM. Pericyte-endothelial crosstalk: implications and opportunities for advanced cellular therapies. Transl Res. 2014;163:296–306. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Padera TP, Stoll BR, Tooredman JB, Capen D, di Tomaso E, Jain RK. Pathology: cancer cells compress intratumour vessel. Nature. 2004;427:695. doi: 10.1038/427695a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baluk P, Hashizume H, McDonald DM. Cellular abnormalities of blood vessels as targets in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:102–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ribatti D, Nico B, Crivellato E, Vacca A. The structure of the vascular network of tumors. Cancer Lett. 2007;248:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ribeiro AL, Okamoto OK. Combined effects of pericytes in the tumor microenvironment. Stem Cell Int. 2015;2015:868475. doi: 10.1155/2015/868475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lofblom J, Feldwisch J, Tolmachev V, Carlsson J, Stahl S, Frejd FY. Affibody molecules: engineered proteins for therapeutic, diagnostic and biotechnological applications. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2670–80. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muller N, Schneider B, Pfizenmaier K, Wajant H. Superior serum half life of albumin tagged TNF ligands. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396:793–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures.