Abstract

Objective

To determine the effect of visual feedback on rate of chest compressions, secondarily relating the forces used.

Design

Randomised crossover trial.

Setting

Tertiary teaching hospital.

Subjects

Fifty trained hospital staff.

Interventions

A thin sensor-mat placed over the manikin's chest measured rate and force. Rescuers applied compressions to the same paediatric manikin for two sessions. During one session they received visual feedback comparing their real-time rate with published guidelines.

Outcome measures

Primary: compression rate. Secondary: compression and residual forces.

Results

Rate of chest compressions (compressions per minute (compressions per minute; cpm)) varied widely (mean (SD) 111 (13), range 89–168), with a fourfold difference in variation during session 1 between those receiving and not receiving feedback (108 (5) vs 120 (20)). The interaction of session by feedback order was highly significant, indicating that this difference in mean rate between sessions was 14 cpm less (95% CI −22 to −5, p=0.002) in those given feedback first compared with those given it second. Compression force (N) varied widely (mean (SD) 306 (94); range 142–769). Those receiving feedback second (as opposed to first) used significantly lower force (adjusted mean difference −80 (95% CI −128 to −32), p=0.002). Mean residual force (18 N, SD 12, range 0–49) was unaffected by the intervention.

Conclusions

While visual feedback restricted excessive compression rates to within the prescribed range, applied force remained widely variable. The forces required may differ with growth, but such variation treating one manikin is alarming. Feedback technologies additionally measuring force (effort) could help to standardise and define effective treatments throughout childhood.

Keywords: CPR; Resuscitation; Child; Feedback, sensory; Chest compression

What is already known on this topic?

Patterns of compressions for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) are variable, and appropriate feedback technologies can improve performance.

Paediatric data on chest compression forces are scarce.

Use of inappropriate compression profiles may be dangerous or ineffective.

What this study adds?

This form of visual feedback reduced excessive rates and brought performance into the prescribed range.

The study revealed more than a fourfold variation in compression forces used by professionals to treat one manikin, independent of the rate of chest compression.

In the clinical scenario, the highest compression (770 N) and residual (50N) forces may have deleterious effects, suggesting value in measuring the efforts required throughout childhood.

Introduction

Since 2010 the International Resuscitation Guidelines have promoted paediatric compression rates of 100–120/min, depressing the chest by at least one-third of its anteroposterior diameter and allowing minimal interruption to compressions.1 2 However, evidence suggests that, even among health professionals, chest displacement during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is variable, compression rates often do not meet the guidelines, and the physiological effects of different patterns of CPR vary.3–9 Guideline-compliant chest compressions (≥51 mm) appear to be associated with longer 24 hour survival in children compared with shallower depths.7 Others have highlighted the need for further scientific debate regarding effective compression depth in children.10 11

Feedback devices can improve CPR performance.12–15 However, commercial devices measuring chest compressions are often not suitable for use with babies and young children.14–18 Many are rigid in composition, which reduces feedback on the chest movement received through the rescuers' hands. Chest compliance reduces with growth, and tactile feedback on full chest recoil may be particularly important in young children, with compliant ribs.16 Quantifying the effort (the force) required for effective chest compression and offload in children of different sizes may offer additional growth-related comparative data to aid paediatric CPR training and performance. Loads simulating ‘leaning’ during CPR have been shown to prevent full chest recoil in anaesthetised children, decrease coronary perfusion pressure, and elevate intrathoracic and right atrial pressures.16 The authors of that study reported that these clinically important haemodynamic effects warranted further study. We are aware of no subsequent paediatric publications on chest compression force.

We therefore devised a technique to measure dynamic force and provide feedback on the rate of chest compressions for paediatric CPR. We conducted a randomised, crossover trial to examine the impact of visual feedback on the rate of chest compressions and to explore any secondary effects of rate feedback on the load profile (compression and residual forces). We hypothesised that visual feedback would bring performance closer to international guidelines, secondarily reducing any variation in force.

Methods

Creation of appropriate technology

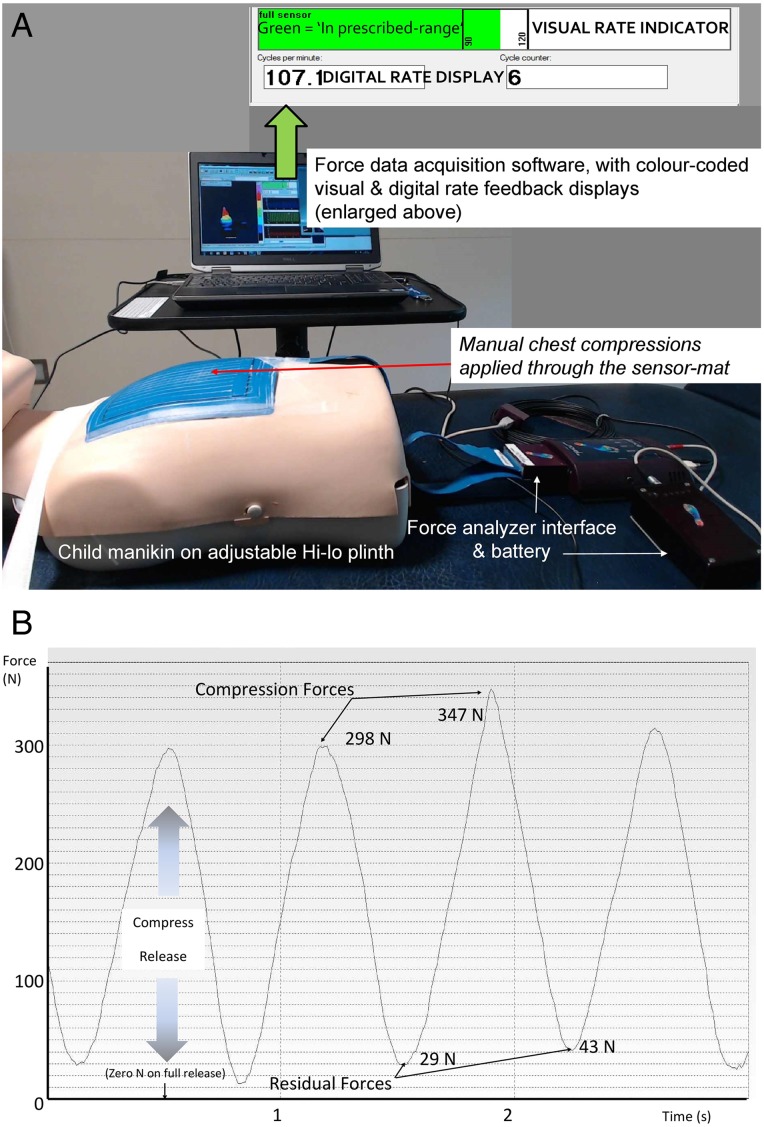

The researchers defined the specifications of a sensor-mat system to measure and provide visual feedback on the rate of chest compressions for CPR in children. The commissioned device measured dynamic pressure and force using 143 individually calibrated capacitive sensors, each sensor measuring 10 mm×10 mm (Pliance x-32 analyzer, Novel GMBH, Munich, Germany) (figure 1). The lightweight mat was ∼1.5 mm thick, conforming fully to the convexity of the chest, sampled at a frequency of 100 Hz over a range of 0–400 kPa, with a drift of <5% and minimal hysteresis. The sensor-mat was calibrated daily with incremental step increases of known air pressure to each sensor using the Novel calibration device. System performance and accuracy have been reported.19

Figure 1.

(A) Prototype equipment providing visual feedback on chest compressions; (B) an example force–time analysis profile.

Descriptive variables (figure 1) of the chest compression were identified as:

Compression force: peak force applied (N)

Residual force: force remaining on decompression (ie, ‘lean load’ N)

Rate: number of compressions per minute (cpm)

The feedback system for rate comprised a digital display (here, 107 cpm) and a colour-coded horizontal sliding bar of the real-time compression rate, symbolising performance within and outside the prescribed range (figure 1).

Study measuring chest compressions for paediatric CPR

The study was conducted in a tertiary hospital and approved by the National Research Ethics Service Committee, Bloomsbury, London (registration number 12/LO/1700, protocol V.1). Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants. Rescuers were informed that all data were anonymised.

Recruitment

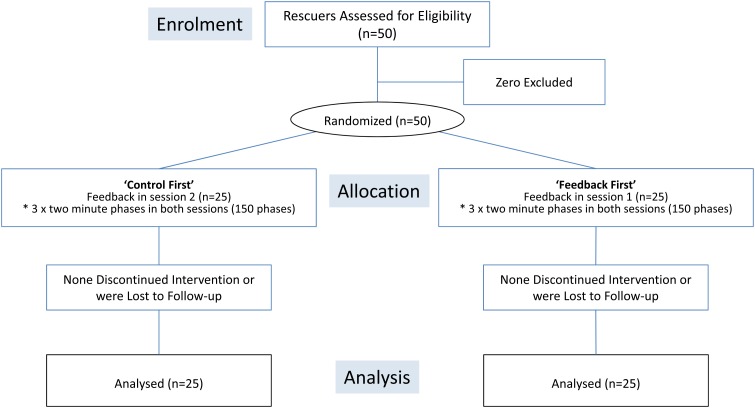

Fifty staff (10 men) were recruited to a randomised, crossover trial between January and July 2015, figure 2. Nursing, medical and paramedical staff who had received hospital training in CPR in the last year were eligible. Individuals were excluded if they refused to give consent or were not in a fit state to perform chest compressions—for example, because of back pain. Recruitment occurred either by direct invitation on the ward (conducted by RKG) or by approaches to staff after their hospital resuscitation training (conducted by DW).

Figure 2.

Consort diagram summarising the randomised rescuers' protocol progression.

Equipment

A paediatric manikin (Laerdal Medical, New York, USA) with an estimated age of 6 years was secured supine on an Akron hi-low plinth (HNE Akron, Ipswich, UK, figure 1). Chest compressions were applied directly through the sensor-mat which was taped in a standardised position to the lower half of the manikin's sternum. The measurement system included the sensor-mat, an electronic interface and a laptop computer for data acquisition and feedback display.

Protocol

Rescuers applied compressions to the paediatric manikin for two sessions. They were informed that this was a compressions-only resuscitation simulation, requiring no airway management and that the researcher would prompt each phase using ‘start’ and ‘stop’ voice cues. Using a computer-generated code list, each rescuer was randomised to receive visual feedback during either the first or the second of the two sessions (RKG). Henceforth, those receiving feedback in the first session will be called the ‘feedback first’ group and those receiving feedback in the second session the ‘control first’ group. The rescuers were given two sets of information. First, they were to continue chest compressions without interruption during each of the three 2 min phases per session, resting for 2 min between phases and for 5 min between sessions. They were reminded of the recommended rate (100–120 cpm), and advised to offload fully between compressions. Rescuers practised five chest compressions on the manikin and were encouraged to adjust the plinth to suit their height. Separately, immediately before each rescuer's feedback session, they were instructed in the visual feedback system. A beat-on-beat, colour-coded three-dimensional (3-D) dynamic pressure profile was also demonstrated. It was emphasised that, since no recommendations exist on the most effective forces to be applied to children, they should deliver what they considered appropriate for a 6-year-old child to depress the chest according to the guidelines.1

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the rate of compressions, expressed as cpm. Secondary outcomes were the compression and residual forces.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS, V.21. Data were collected in the three phases per session (300 recordings); the phases were then averaged by session, resulting in 100 measures, two per rescuer. The effect of providing feedback on rate was estimated using univariable and multivariable linear mixed-effects models, with fixed effects for session number and randomisation order (and their interaction) plus a random effect for rescuer. Secondary analysis estimated the effect of rate feedback on force. The trial was reported according to the Consort 2010 statement, paying attention to numerical presentation.20 21

Sample size

Comparing the results of a group of 50 rescuers would allow detection of a between-subject difference of 0.6 SD with 80% power and 5% significance. Assuming a between-subject SD of 13, 0.6 SD equates to a difference in rate of 8 cpm.

For the within-subject comparisons based on 50 rescuers and focusing on the interaction between feedback condition and order of presentation, the study was designed to have 80% power at 5% significance to detect an effect size of 6 cpm.

Results

The age, gender and general characteristics of the two randomisation groups were similar, as shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the two groups defined according to intervention allocation

| Characteristics | Control first, n=25 | Feedback first, n=25 |

|---|---|---|

| Profession: | ||

| Nurse ≥ 5 y experience | 8 | 10 |

| Nurse < 5 y experience | 6 | 6 |

| Teaching / research staff | 5 | 5 |

| Doctor | 6 | 4 |

| Female | 20 | 20 |

| Right-handed | 23 | 21 |

| Age (y) | 33 (9) | 33 (8) |

| Weight (kg) | 66 (16) | 69 (16) |

| Height (cm) | 165 (8) | 169 (10) |

| BMI | 24 (5) | 24 (5) |

Values are mean (SD).

BMI, body mass index.

All the rescuers completed the protocol phases, from recruitment through randomisation to data analysis (figure 2).

Primary outcomes

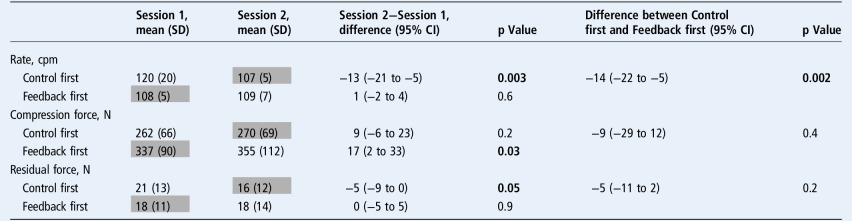

Table 2 summarises the results for chest compressions by session and feedback order.

Table 2.

Summary of rate and force of chest compressions for CPR according to session and intervention order

|

Shaded boxes denote feedback sessions; p≤0.05. Bold indicates significance.

cpm, compressions per minute; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

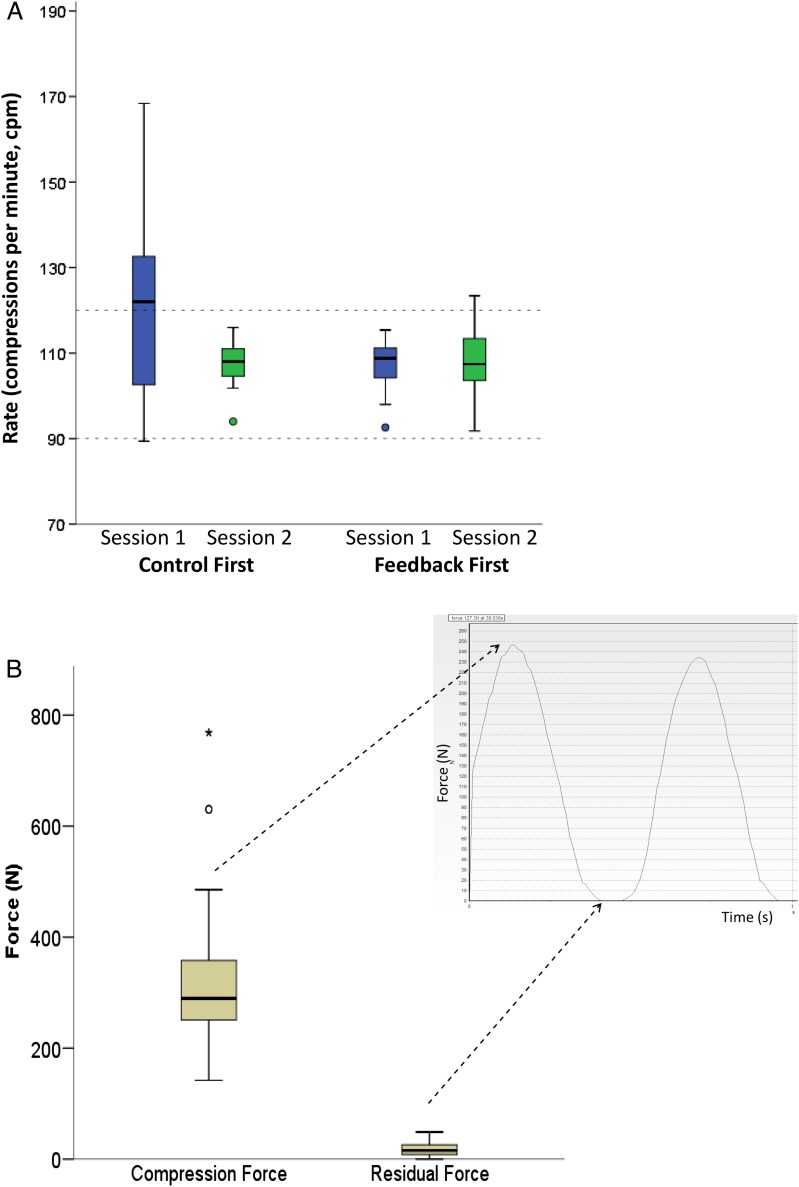

The rate varied widely (mean 111 cpm; SD 13; range 89–168), with a fourfold difference in SD during session 1 between those receiving and not receiving feedback. Of the results in the two sessions for the two groups, in session 1 the control first group (receiving feedback second) stood out, with both mean and SD raised, while feedback in session 2 normalised the rates (table 2 and figure 3A). The interaction of session by feedback order was highly significant, indicating that this difference in mean rate between sessions was 14 cpm less (−22 to −5, p=0.002) in those given feedback first compared with those given it second.

Figure 3.

Variability in (A) rate and (B) force of chest compressions applied to the same manikin by 50 rescuers. (A) Effect of visual feedback on rate, randomised by order, and (B) compression and residual forces. (A) The horizontal broken lines represent the feedback limits set to indicate the desired rate.

Secondary outcomes

Figure 3B demonstrates the wide variation in compression force applied to the manikin (mean 306 N (SD 94); range 142–769), a more than fivefold difference. Before averaging, the highest recorded force exceeded 800 N.

As summarised in table 2, forces were greater and more variable in session 1 among those receiving feedback compared with those not (337 (90) vs 262 (66), p=0.001). Overall, those receiving feedback second (control first) used significantly lower compression force (adjusted mean difference −80 (95% CI −128 to −32), p=0.002). The mean residual force of 18 N (SD 12, range 0–49) was the same in both groups.

Discussion

Statement of findings

Rate

Use of visual feedback ensured CPR performance within the prescribed rate range. Without feedback, many rescuers exceeded the guidelines, which could result in poorer outcome. This is shown by the wide SD of the control first group in session 1 (table 2). Their median rate was above 120 cpm (figure 3A), demonstrating that more than half of these rescuers exceeded the upper prescribed limit. The control first group in session 1 were the only rescuers behaving ‘naturally’, as in the other three sessions, rescuers were, or had just been, exposed to feedback. Since all rescuers were reminded of the guidelines before ‘treating’ the manikin, this finding suggests that judging compression rate is difficult and rescuers ‘over-try’ to meet the recommendations. When external chest compressions were first promoted in the 1960s, it was suggested that ‘anyone, anywhere’ with ‘two hands’ could perform effective chest compressions for resuscitation.22 However, our research suggests that, without real-time feedback, it is difficult to deliver appropriate chest compressions for children.

Force

Strikingly, the forces delivered to a single manikin showed unexpectedly large variation. In the control first group, as their rate slowed with feedback in the second session, so the residual force maintained between compressions decreased. While the most clinically effective range of forces in children has yet to be determined, both extreme loading and incomplete offloading of force may adversely impact outcome.16 17 As chest compliance varies greatly with age, lower treatment forces would be expected for babies compared with teenagers. Precise force categories required for effective sternal depression are likely to be influenced by both the child's clinical condition and their age and body size.23 Young children and the elderly are two groups of patients likely to be vulnerable to chest injury and inefficient external chest compression.10 11 24 25 The ability to measure and compare the effort required throughout childhood is integral to optimising the training of paediatric healthcare professionals, creating appropriate instincts and reflexes through immediate feedback both in hospital and outside.

Feedback effect

In the control first group, their compression force appeared to be established in that first ‘natural’ session, unlike the feedback first group whose force increased in session 2. While no feedback system for force was provided, a 3-D pressure profile of real-time data was displayed on the computer screen. The rescuers were told to focus on the rate feedback display, applying whatever force they felt was clinically appropriate for a 6-year-old, as no guidelines exist for force. The mere presence of the pulsing 3-D display may have motivated some in the feedback first group to push harder on the manikin from the outset, as shown in table 2. Just as different feedback systems have been shown to produce varying responses, these extraneous data may have been distracting.12

Comparison with published literature

This study concurs with others showing performance of chest compressions at variable and excessive rates.4 5 13 26 Valuable paediatric data have been published regarding differing compression depths, patterns of CPR and patient survival.4 7–9 17 27 Outcome is often related to treatment duration rather than force application.28

Paediatric force

Few data exist regarding forces required throughout childhood, specifically in younger children.2 29 A hospital-based study of eight children aged below 8 (four children in each arm, non-randomised) demonstrated that, even in an experienced paediatric centre using an audiovisual feedback facility, their cumulative assessment measure of ‘excellent CPR’ was achieved in 28% of the treatments with feedback and 0% without.4 Feedback resulted in 80% of chest compressions falling within the recommended rate. As was the case here, most benefit was derived from slowing excessive rates. There was no direct measure of compression force but ‘quality CPR’ included the measure of residual lean load <2.5 kg, equating to approximately 25 N. Residual forces exceeding 25 N were recorded in this study.

In an earlier study, the group determined paediatric thoracic force-deflection characteristics for CPR.30 Chest compression forces of 309 (SD 55) N were recorded in 18 subjects aged between 8 and 22 years. The researchers combined these data with their earlier results, reporting age-related changes in thoracic mechanics, the stiffness of the thorax increasing from youth to middle age and decreasing in the elderly. They highlighted a need to increase the sample size and age range studied. Their results concur with equivalent values of 306 (SD 94) N recorded here, this study recording greater extreme forces of almost 800 N. The earlier publication was conducted in older subjects, in whom proportionately higher forces might have been expected, to depress their stiffer chests.19

Compression variables and feedback

CPR measurement systems often derive chest compression variables—for example, effective compression ratio and fraction, and duty cycle (the ratio of compression to relaxation).31 32 Researchers have examined the effects of different duty cycles on cerebral and aortic perfusion, in animals, by modelling and latterly in human subjects.33 34 Both duty cycle and residual force (or lean load) would appear to be physiologically important variables. Audiovisual feedback has been used in isolation and in combination with post-event debriefings.35 36 In children and adults, adhering to the 2010 International Guidelines-recommended depth of at least 51 mm could improve outcomes from cardiac arrest.4 6 However, the use of accelerometers may result in overestimation of chest displacement and may be influenced by variables such as the composition of the underlying surface on which CPR is performed.9 18 37 38

Study strengths

Each of the 50 rescuers performed a total of 12 min of chest compressions on the manikin, providing robust results from, on average, over 1300 compressions. The thin sensor-mat conformed exactly to the manikin and to children's chests.19 It allowed the rescuer immediate feedback through their hands regarding the child's chest depression and recoil responsiveness, unlike other more rigid feedback systems used for older subjects.14 15 39

Study limitations

This was not a crisis scenario and the research was conducted on a manikin, which cannot be considered an ideal replacement for an unresponsive child. However, it was important to standardise the subject in order to examine variability in rescuers' performance. It is both unethical and impossible to apply chest compressions for CPR to healthy children.

Clinical implications

Direct measurement of manual forces applied to children's chests could yield valuable insight when used in combination with simultaneous recording of clinical response. Such studies should help clarify the profiles required to increase intrathoracic pressure and achieve effective coronary perfusion pressure for children of different ages.33 There is heterogeneity of outcomes used to date in such clinical trials.40 While measures such as arterial blood pressure and end-tidal CO2 are useful in high-tech environments, it has been proposed that definition of the specific physiological markers of most use in children may suggest a unique direction for paediatric CPR studies.29

Conclusion

This study highlights the variability of chest compression profiles for paediatric CPR. While visual feedback reduced excessive rates to ensure performance within a prescribed rate range, applied force showed alarming variation. Incomplete offload between compressions was also recorded. Feedback technologies that measure the force required to reverse cardiac arrest could provide the tools to define the inter-related details of paediatric CPR. Understanding factors promoting effective chest compressions from birth to adulthood could help to optimise performance and thus improve children's survival.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the hospital staff at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children for their support and participation. Thanks also to Heather Chesters (Librarian, UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health) for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Emmanouil Bagkeris at @ebagkeris

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design and execution of this research and to manuscript preparation and approval.

Funding: This research was funded by Sparks (Sport Aiding Medical Research for Kids) medical research charity (11ICH04), and supported by MRC grant number MR/M012069/1, the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust and University College London. Tim Cole was supported by MRC grant MR/M012069/1.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: National Research Ethics Service Committee; Bloomsbury, London (registration number 12/LO/1700).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kleinman ME, de Caen AR, Chameides L, et al. Part 10: Pediatric basic and advanced life support: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations. Circulation 2010;122:S466–515. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maconochie IK, Bingham R, Eich C, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: Section 6. Paediatric life support. Resuscitation 2015;95:223–48. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kampmeier TG, Lukas RP, Steffler C, et al. Chest compression depth after change in CPR guidelines—improved but not sufficient. Resuscitation 2014;85:503–8. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutton RM, Niles D, French B, et al. First quantitative analysis of cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality during in-hospital cardiac arrests of young children. Resuscitation 2014;85:70–4. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin PS, Kemp AM, Theobald PS, et al. Do chest compressions during simulated infant CPR comply with international recommendations? Arch Dis Child 2013;98:576–81. 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vadeboncoeur T, Stolz U, Panchal A, et al. Chest compression depth and survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2014;85:182–8. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sutton RM, French B, Niles DE, et al. 2010 American Heart Association recommended compression depths during pediatric in-hospital resuscitations are associated with survival. Resuscitation 2014;85:1179–84. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sutton RM, Wolfe H, Nishisaki A, et al. Pushing harder, pushing faster, minimizing interruptions … but falling short of 2010 cardiopulmonary resuscitation targets during in-hospital pediatric and adolescent resuscitation. Resuscitation 2013;84:1680–4. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.07.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutton RM, French B, Nishisaki A, et al. American Heart Association cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality targets are associated with improved arterial blood pressure during pediatric cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2013;84:168–72. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.08.335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kao PC, Chiang WC, Yang CW, et al. What is the correct depth of chest compression for infants and children? A radiological study. Pediatrics 2009;124:49–55. 10.1542/peds.2008-2536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braga MS, Dominguez TE, Pollock AN, et al. Estimation of optimal CPR chest compression depth in children by using computer tomography. Pediatrics 2009;124:e69–74. 10.1542/peds.2009-0153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeung J, Davies R, Gao F, et al. A randomised control trial of prompt and feedback devices and their impact on quality of chest compressions—a simulation study. Resuscitation 2014;85:553–9. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin P, Theobald P, Kemp A, et al. Real-time feedback can improve infant manikin cardiopulmonary resuscitation by up to 79%—a randomised controlled trial. Resuscitation 2013;84:1125–30. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeung J, Meeks R, Edelson D, et al. The use of CPR feedback/prompt devices during training and CPR performance: a systematic review. Resuscitation 2009;80:743–51. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wutzler A, Bannehr M, von Ulmenstein S, et al. Performance of chest compressions with the use of a new audio-visual feedback device: a randomized manikin study in health care professionals. Resuscitation 2015;87:81–5. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glatz AC, Nishisaki A, Niles DE, et al. Sternal wall pressure comparable to leaning during CPR impacts intrathoracic pressure and haemodynamics in anaesthetized children during cardiac catheterization. Resuscitation 2013;84:1674–9. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutton RM, Friess SH, Bhalala U, et al. Hemodynamic directed CPR improves short-term survival from asphyxia-associated cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2013;84:696–701. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nuthall G, de Caen A. “How deep is your love?” Choosing the most appropriate depth for paediatric chest compression. Resuscitation 2014;85:1125–6. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gregson RK, Stocks J, Petley GW, et al. Simultaneous measurement of force and respiratory profiles during chest physiotherapy in ventilated children. Physiol Meas 2007;28:1017–28. 10.1088/0967-3334/28/9/004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2010;1:100–7. 10.4103/0976-500X.72352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole TJ. Too many digits: the presentation of numerical data. Arch Dis Child 2015;100:608–9. 10.1136/archdischild-2014-307149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kouwenhoven WB, Jude JR, Knickerbocker GG. Closed-chest cardiac massage. JAMA 1960;173:1064–7. 10.1001/jama.1960.03020280004002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maltese MR, Arbogast KB, Nadkarni V, et al. Incorporation of CPR data into ATD chest impact response requirements. Ann Adv Automot Med 2010;54:79–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hellevuo H, Sainio M, Nevalainen R, et al. Deeper chest compression—more complications for cardiac arrest patients? Resuscitation 2013;84:760–5. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lederer W, Mair D, Rabl W, et al. Frequency of rib and sternum fractures associated with out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation is underestimated by conventional chest X-ray. Resuscitation 2004;60:157–62. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2003.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamrick JT, Fisher B, Quinto KB, et al. Quality of external closed-chest compressions in a tertiary pediatric setting: Missing the mark. Resuscitation 2010;81:718–23. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sutton RM, Case E, Brown SP, et al. A quantitative analysis of out-of-hospital pediatric and adolescent resuscitation quality–A report from the ROC epistry-cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2015;93:150–7. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berg RA, Nadkarni VM, Clark AE, et al. Incidence and Outcomes of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in PICUs. Crit Care Med 2016;44:798–808. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Caen AR, Duff JP. Feedback during CPR in younger children: Will it help us do the right thing? Resuscitation 2014;85:7–8. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maltese MR, Castner T, Niles D, et al. Methods for determining pediatric thoracic force-deflection characteristics from cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Stapp Car Crash J 2008;52:83–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greif R, Stumpf D, Neuhold S, et al. Effective compression ratio–a new measurement of the quality of thorax compression during CPR. Resuscitation 2013;84:672–7. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheskes S. Resuscitation duty cycle in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: is 40 the new 50? Resuscitation 2015;87:A5–6. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koeken Y, Aelen P, Noordergraaf GJ, et al. The influence of nonlinear intra-thoracic vascular behaviour and compression characteristics on cardiac output during CPR. Resuscitation 2011;82:538–44. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson BV, Coult J, Fahrenbruch C, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation duty cycle in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2015;87:86–90. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braun L, Sawyer T, Smith K, et al. Retention of pediatric resuscitation performance after a simulation-based mastery learning session: a multicenter randomized trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2015;16:131–8. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolfe H, Zebuhr C, Topjian AA, et al. Interdisciplinary ICU cardiac arrest debriefing improves survival outcomes*. Crit Care Med 2014;42:1688–95. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perkins GD, Kocierz L, Smith SC, et al. Compression feedback devices over estimate chest compression depth when performed on a bed. Resuscitation 2009;80:79–82. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maconochie I, Bingham R. How to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation: an opportunity for technology development. Arch Dis Child 2013;98:571–2. 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zapletal B, Greif R, Stumpf D, et al. Comparing three CPR feedback devices and standard BLS in a single rescuer scenario: a randomised simulation study. Resuscitation 2014;85:560–6. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whitehead L, Perkins GD, Clarey A, et al. A systematic review of the outcomes reported in cardiac arrest clinical trials: the need for a core outcome set. Resuscitation 2015;88:150–7. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]