Abstract

Detection and tracking of stem cell state are difficult due to insufficient means for rapidly screening cell state in a noninvasive manner. This challenge is compounded when stem cells are cultured in aggregates or three-dimensional (3D) constructs because living cells in this form are difficult to analyze without disrupting cellular contacts. Multiphoton laser scanning microscopy is uniquely suited to analyze 3D structures due to the broad tunability of excitation sources, deep sectioning capacity, and minimal phototoxicity but is throughput limited. A novel multiphoton fluorescence excitation flow cytometry (MPFC) instrument could be used to accurately probe cells in the interior of multicell aggregates or tissue constructs in an enhanced-throughput manner and measure corresponding fluorescent properties. By exciting endogenous fluorophores as intrinsic biomarkers or exciting extrinsic reporter molecules, the properties of cells in aggregates can be understood while the viable cellular aggregates are maintained. Here we introduce a first generation MPFC system and show appropriate speed and accuracy of image capture and measured fluorescence intensity, including intrinsic fluorescence intensity. Thus, this novel instrument enables rapid characterization of stem cells and corresponding aggregates in a noninvasive manner and could dramatically transform how stem cells are studied in the laboratory and utilized in the clinic.

Keywords: stem cells, endogenous fluorophores, fluorescence, multiphoton microscopy, flow cytometry, differentiation

Introduction

The unique ability of stem cells to exist in multiple states (i.e., pluripotent, multipotent, mature somatic) provides a powerful tool for developmental biology, pharmaceutical science, and regenerative medicine. Ironically, this same property hinders rapid progress in these fields due to the current lack of experimental control to maintain stem cells or their progeny in a specified state. One primary challenge is defining and executing screening protocols that can non-invasively monitor the status (i.e., viability, proliferative capacity, functional competence) of a given population of cells. The complexity of such screening is amplified in biologically relevant three-dimensional (3D) constructs, where not only is accessing the cells for screening more difficult but the status of cells can be altered if they are removed from the construct for characterization (Leong et al., 2008; Phillips et al., 2008; Carpenedo et al., 2009). In addition, certain characterization approaches, such as those involving antibody or peptide binding, either require the use of fixed tissue or can alter stem cell state, thereby prohibiting clinical use (Elknerova et al., 2007; Kajiwara et al., 2008). Continued advances in stem cell research depend on the development of new technologies that allow for accurate, noninvasive, and enhanced-throughput assessment of stem cell state at both the single cell and 3D (i.e., cell aggregate or tissue construct) level and permit the sorting of populations based on this assessment.

Flow cytometers are well-established research and clinical instruments that not only provide automated, quantifiable data on cellular phenotype, differentiation, and metabolic state but can also sort populations based on these parameters. Unlike RNA and protein-based approaches (i.e., RNA or protein microarrays, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction, Western blot or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays), flow cytometry can be used to analyze intact cells, permitting the study of purified populations over time. However, until recently, standard flow cytometers were limited to the analysis of single cells with diameters typically less than 20 µm. Union Biometrica (Holliston, MA, USA) has developed the COPAS (Complex Object Parametric Analyzer and Sorter) flow cytometer with the capacity to analyze and sort particles with diameters as great as 1500 µm. Unfortunately, the COPAS system has some limitations, including the requirement for extrinsic fluorescent labels and the inability of the instrument to optically detect signals within large aggregates (Fernandez et al., 2005). In addition, further adoption and adaptation of flow cytometry systems is limited by the closed-frame nature of traditional systems and restricted access to most flow cytometry acquisition software packages. Therefore, the development of an instrument to address these limitations would substantially advance stem cell biology and related fields.

Most biomarkers detected by flow cytometry for identifying cell state and function correspond to protein expression and thus necessitate the application of extrinsic labels or genetic modification prior to analysis. Stem cells are no exception; various proteins have been identified to discern stem cell status, to elucidate the molecular mechanisms that regulate pluripotency and differentiation and, ultimately, to guide stem cell therapies. Recent studies have begun to explore the possibility that endogenous characteristics of stem cells and their progeny might be equally useful for screening cell populations (Reyes et al., 2006; Guo et al., 2008; Teisanu et al., 2009; Uchugonova & Konig, 2008). Endogenous fluorophores are known indicators of cellular state, providing information about the physical and chemical condition of the cell and its interactions with the microenvironment. In particular, there is great interest in noninvasive imaging techniques that would allow one to monitor changes in metabolism between normal and diseased states.

One potentially powerful method to study metabolism in vivo is to monitor the intrinsic fluorescence of metabolic intermediates, such as reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH). NADH plays a key role as a carrier of electrons and is involved in many important metabolic pathways, for example, glycolysis (Berg et al., 2002). NADH has two forms in cells: free and protein bound. Most bound NADH is found in the mitochondria while free NADH exists in both the cytoplasm and the mitochondria (Wakita et al., 1995; Blinova et al., 2005; Belenky et al., 2007). NADH fluorescence intensity changes have been used to study cell metabolic activity in vivo for many years (Chance et al., 1962; Pappajohn et al., 1972; Lakowicz et al., 1992; Ramanujam et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 2002, 2006). Additionally, recent studies have used multiphoton laser scanning microscopy (MPLSM) to characterize NADH and the intrinsic metabolite flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) in cancer cells and characterize the metastatic potential (Bird et al., 2005; Skala et al., 2005, 2007). These studies and others (Kirkpatrick et al., 2007; Provenzano et al., 2008; Conklin et al., 2009) have helped define the experimental conditions for our multiphoton fluorescence excitation flow cytometry (MPFC) trials to examine NADH. For example, the metabolic state of carcinoma cells, as detected by endogenous fluorescent metabolic intermediates, has been correlated with the identification and metastatic potential of cancers, in both animal and human models (Skala et al., 2005). Human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) undergo a number of changes in mitochondrial characteristics as they differentiate, including an increase in mitochondrial mass and adenosine triphosphate production, suggestive of metabolic differences (Cho et al., 2006). Additionally, recent evidence indicates that changes occur in the levels of a variety of metabolites as mouse ESCs differentiate into embryoid bodies, including a decrease in the threonine-dependent conversion of NAD+ to NADH (Wang et al., 2009). Given the known cellular differences of cells with different developmental potentials, it is likely that imaging endogenous fluorophores, such as NADH and FAD, in stem cells will provide biologically meaningful information that could be utilized to distinguish cells in different states of maturation.

The utility of endogenous fluorescence as a “fingerprint” for identifying cells in a given state requires appropriate technologies for visualizing those endogenous signals. MPLSM is uniquely suited to detect endogenous fluorophores, particularly in 3D structures due to the broad tunability of its excitation sources, as well as improved deep sectioning, viability, and signal-to-noise compared to traditional optical approaches. MPLSM is a nonlinear optical sectioning technique that allows thick biological sections to be imaged noninvasively via absorption of two or more low-energy photons in the near infrared range. Sufficient energy for two photon excitation is only present at the plane of focus such that, unlike other fluorescence microscopy approaches, no out-of-plane signal interference and photobleaching occurs. For this reason, in conjunction with the fact that the longer wavelengths of light used are more immune to scattering and less phototoxic, the effective imaging depth can greatly exceed conventional confocal microscopy (Denk et al., 1990; Centonze & White, 1998; Squirrell et al., 1999).

Effective imaging depth is especially important in the context of the embryoid body (EB), the common multicellular intermediate between ESCs or induced pluripotent stem cells and mature cells. The typical EB size range is approximately 100–500 µm, and so fluorescence signals that may be generated at the center are difficult to detect with current confocal microscopy or flow cytometry systems but are readily attained with MPLSM. Furthermore, the emergence of multiphoton compatible techniques such as second harmonic generation (SHG) imaging of biological structures (Campagnola et al., 2002; Campagnola & Loew, 2003), fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (Szmacinski et al., 1994), and combined spectral lifetime imaging microscopy (Bird et al., 2004) extend the applications for MPLSM. These features, when utilized either individually or especially in combination, provide significant tools to obtain detailed multidimensional data from either exogenous or endogenous fluorophores associated with stem cells.

Given the unique properties of MPLSM and their potential for stem cell imaging, we hypothesized that a novel MPFC instrument could be developed to accurately probe cells deep in the interior of multicellular aggregates or tissue constructs in an enhanced-throughput manner. Furthermore, if this system is used to excite endogenous fluorophores of cells as potential intrinsic biomarker candidates, the application of exogenous fluorescent labels is thereby avoided and fixation is unnecessary. Others have considered the possibility of a multiphoton flow instrument (or multiphoton flow cytometry) (Zhong et al., 2008; Diaspro, 1999; Hanninen et al., 1999) for analysis of cells and cellular aggregates in turbid and nonuniform flow conditions, such as may be encountered in blood vessels in vivo. In the future, our intent is to devise a fluid-controlled in vitro system such that cellular and multicellular entities might not only be analyzed but also sorted based on endogenous fluorescent properties. Cells sorted with this system, in principle, would be viable and their cell-to-cell contacts unperturbed, unlike the output of current flow cytometry sorting systems, and so could be used directly for clinical application.

In the course of constructing a proof-of-concept MPFC instrument, we sought to incorporate an open frame hardware system structure and modular acquisition software package to yield an accurate, noninvasive, and enhanced-throughput system to assess stem cell state (including metabolic, viability, and functional status) at both the single cell and 3D level. The instrument we have developed is comprised of a flow cell through which large particles stream past a light interrogation point, an optics system with two-photon excitation capability, and data acquisition software to quantify the data (Fig. 1). Here we describe the instrument design as well as validate the proof of concept prototype, in terms of integrity of the width of the sample stream, particle recovery, speed of image capture, accuracy of image capture, and accuracy of measured fluorescence intensity. The latter analyses were conducted on both synthetic fluorescent beads and stem cell aggregates, including analysis of both extrinsic and intrinsic fluorescence. Results indicate particle recovery of ≥81% and nearly 100% accuracy of size compared to static measures. Extrinsic fluorescence of a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-linked cardiac reporter stem cell line was also monitored on the MPFC prototype and could be readily discerned with histogram analysis confirming the fraction of stem cells undergoing cardiac differentiation was consistent between static acquisition (66%) and MPFC (60%). In addition, intrinsic fluorescence intensity could be readily discerned and correlated strongly with images acquired in preflow static mode with the same MPLSM optics (P = 0.46). Future studies aim to robustly define intrinsic fluorescent profiles indicative of a particular cell state (i.e., viable, proliferative, differentiating) that could dramatically transform the manner in which stem cells are studied in the laboratory and utilized in the clinic.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the MPFC system. A microfabricated flow cell is placed on a multiphoton laser scanning microscope equipped with a Ti:Sapphire laser for excitation, photomultipliers, and scanning optics and electronics for signal collection. Sample fluid (i.e., biological specimens or beads) and sheath fluid are introduced into the microchannels using syringe pumps and associated tubing. See the Materials and Methods and the Results sections for additional details.

Materials and Methods

Construction of Flow Cell

The flow cell was constructed using standard photolithographic and soft lithography techniques (Dittrich & Schwille, 2003; Studer et al., 2004; Huh et al., 2005; Blake et al., 2007; Guo et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2008). Two 500 µm layers of SU-8 2150 negative photo resist were spun onto a silicon wafer substrate by manipulating spin speed and spin time. Soft bakes and postexposure bakes of the photo-resist layer were performed according to manufacturer’s specifications (Microchem, Newton, MA, USA). Liquid phase polydimethyl-siloxane (PDMS) (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA) mixed at a 10:1 base to curing agent ratio was poured over the silicon master and heated for 1 h at 95°C. Three inlet ports (two for sheath channels, one for sample) and one outlet were cored out of the PDMS device using a 16-gauge blunt needle. PVC Tygon tubing (0.1 cm I.D., 0.2 cm O.D.) created a leak-free seal when inserted into the inlet and outlet ports of the elastomeric PDMS. A 0.15 mm thick glass cover slip was irreversibly bonded to the PDMS by oxygen plasma treatment (Haubert et al., 2006). The sheath syringe fed into a three-way mechanical valve that split the stream to the left and right inputs of the flow cell (Fig. 2A,B). This was implemented to temporarily flush the flow cell of air bubbles and manually calibrate the focused stream with fluorescein dye before testing. The sheath inlet channels were designed to be 2 mm wide, the sample channel 1 mm wide, and the outlet channel 5 mm wide and 76 mm long (Fig. 2A,B). The large width of the outlet channel was designed to decrease the average (and maximum) velocity of the large particles, to accommodate a particle scanning speed of 2–3 frames/second.

Figure 2.

A microfabricated flow cell to accommodate large particles. Sheath and sample volumes were introduced into a PDMS microfabricated flow cell and flow rates were controlled via syringe pumps. A modular stage insert was fabricated to protect the flow cell from damage and to allow for turn-key application of the flow cell to other microscopy systems. A: Top-down view of the microfabricated flow cell. Features of the flow cell include waste output/reservoir drop, sample input and sheath input, and an interrogation point where optical analysis occurs. Scale bar, 5 mm. B: Top-down photograph of the flow cell housed in the modular stage insert. Features of the stage insert include a series of tubing adaptors that allow the flow cell to be easily added to and removed from the MPLSM system. C: Hydrodynamic control of the sample path. Sample fluid was labeled with fluorescein and sheath and sample flow rates were controlled via syringe pumping. Images captured using the WiscScan software illustrate how varying the sheath to sample flow velocity ratios (α) alter the width of the sample stream. D: Comparison of the predicted focused width with experimental data at different ratios of sheath volumetric flow rate to sample volumetric flow rate (100–1,000 and 50–500 µL/min, respectively). Model predictions were based on those previously published (Lee et al., 2006).

Integration of Flow Cell and MPLSM Systems

Two separate programmable syringe pumps (Braintree Scientific Inc., Braintree MA, USA, model BS-8000/9000), housed 20 cc syringes to drive sheath and sample liquids through the attached tubing and flow cell. The flow cell was mounted on a lengthwise adjustable stage insert compatible with most microscope stages and therefore easily adjusted via the xy stage controller and z-focus. The sheath to sample rate ratio α is reported as the summed volumetric flow rates of both sheath ports over the volumetric flow rate of the sample port. The ratio utilized throughout this work was α = 2.0 and maximum volumetric flow rate of the outlet channel equal to 900 µL/min. Samples were interrogated with either 890 nm or 780 nm wavelength light and images collected with Nikon lenses (Nikon, Melville, NY), either a 1.0 mm WD, 0.75 NA, 20× air lens or a 1.2 mm WD, 0.75 NA, 10× air lens with a typical scan speed of approximately 2.33 frames/second and resolution of 256 × 256.

Validation of Flow Stream Widths

Five drops of fluorescein dye were added to 20 mL of deionized water and loaded into the sample syringe to verify the boundaries of the focused sample stream in the flow channel. Focused stream widths were recorded on the MPFC set up and measured with ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) (Collins, 2007). Theoretical stream widths were calculated based on previous studies of hydrodynamic focusing in rectangular microchannels (Lee et al., 2006). By conservation of mass, the width of the focused stream can be determined using

where wf is the width of the focused stream, w0 is the width of the outlet channel, Qi is the volumetric flow rate of the sample inlet, Qs is the volumetric flow rate of the two sheath inlets combined, and γ represents the velocity ratio υf/υ0, where υf and υ0 correspond to the average flow velocities in the focused stream and the outlet channel, respectively. Nine different sheath-to-sample ratios within a pertinent range were analyzed while testing three different volumetric flow rates for each data point to ensure reproducibility at different Reynold’s numbers 0.9–9.0.

Validation of Size and Fluorescence Intensity Using Polystyrene Fluorescent Microspheres

Fluorescent microspheres, approximately 100, 200, and 400 µm in diameter (Duke Scientific Corporation, Palo Alto, CA, USA), were suspended in 1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% Triton X-100. These microspheres were used to calibrate optical parameters and verify proper functioning of the fluidic component.

Cell Culture and EB Formation

Mouse ESC lines used were D3 (Miller-Hance et al., 1993) and HM1 αMHC::GFP. The αMHC::GFP cell line was generated by transfecting (Lipofectamine, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) a plasmid containing the 5.5 kb promoter region of the α-myosin heavy chain (α-MHC) gene driving enhanced GFP (Martinez-Fernandez et al., 2006) into HM1 ES cells (Fijnvandraat et al., 2003) to express GFP in cardiac myocytes. ESCs were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) with the addition of Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF, Millipore/Chemicon, Billerica, MA, USA) at 2,000 U/mL and Bone Morphogenic Protein 4 (BMP-4, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) at 10 ng/mL (Ying et al., 2003) in 5% CO2 at 37°C. EBs were made via the hanging drop method (Maltsev et al., 1993). Briefly, ESCs were trypsinized and resuspended in DMEM with 10% FBS (no LIF or BMP-4) to 1.6 × 104 cell/mL. This cell suspension was used to make 30 µL hanging drops in 100 mm petri dishes over PBS. EBs were harvested on days 8 and 12 after formation of hanging drops, placed into a 50 mL conical tube, and allowed to settle. Supernatant was removed, and EBs were resuspended in 20 mL DMEM with 10% FBS and remained in suspension, at 37°C until used in the flow cell (<4 h). A small number of EBs used were plated onto 60 mm gelatinized culture dishes to confirm the ability of those EBs to attach and form contracting cardiomyocytes.

Analysis and Recovery of EBs on MPFC

Deionized water was loaded into the sample and sheath syringes and run through the system for 5 min. Subsequently, 10 mL of 1X PBS containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) was loaded into the sample syringe and run through the sample tubing and the flow cell. BSA was used to bind nonspecific protein binding sites in the tubing and flow cell and so prevents cell adhesion to the biomaterials present in the system. EBs were counted by the observer before being suspended in 10 mL of DMEM complete medium and loaded into the sample syringe. The MPLSM Ti:Sapphire laser (Spectra Physics Tsunami, Newport Corporation, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was tuned at 780 nm excitation for NADH detection and 890 nm excitation (with a 520/35 band-pass emission filter, Chroma Technology Corporation, Rockingham, VT, USA) for GFP detection (excitation 489 nm, emission 509 nm). Power and gain settings of the laser were set such that less than 5% of pixels were saturated, and background noise was kept to a minimum. Sheath-to-sample ratios were kept constant at 2, with a total volumetric flow rate (combined sheath and sample volumetric flow rates) of 600 µL/min. A sample volumetric flow rate of 200 µL/min was used when analyzing EBs. Bright-field and intensity images were collected using in-house developed software (WiscScan) for both acquisition and quantitative and morphological analysis. A subpopulation of EBs were imaged statically in a glass bottom dish (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA, USA) before and after MPFC analysis, under the same imaging conditions used for flow conditions. Fluorescence and size measurements of EBs were made using ImageJ software (Collins, 2007). For analysis, threshold values were set such that less than 0.1% of pixels on a background image were saturated for all conditions. To determine the delivery rate of EBs from the syringe to the MPFC, the sample syringe was disconnected from the system and sample was injected for a specified amount of time into a 15 mL conical tube for counting. The concentration of EBs was designated as the input for analysis, and particle counts were normalized based on the average particle recovery per minute for at least three trials. The output particle count was determined by introducing EBs into the MPFC and collecting for the same amount of time as the input sample. Output counts were determined by manually counting a representative fraction of particles collected in the waste reservoir. Average particle count per minute was normalized to input values. Polystyrene bead (100, 200, and 400 µm) recovery was determined in the same manner.

Statistical Analyses

For comparison of size and fluorescence intensity levels of beads and cell aggregates under static and flow (MPFC system) conditions, a normal distribution was assumed and one-way analyses of variance and student t-test for unpaired samples were used. Data were analyzed with JMP 5.0.1 for Windows (SAS Institute, Inc., Carey, NC, USA). A 95% confidence (P < 0.05) interval was applied as the criterion to determine statistically significant differences.

Results

Instrument Design

The MPFC system integrates three components: fluidics, optics, and data acquisition. These components are linked as illustrated in the comprehensive schematic (Fig. 1). A detailed description of each component is provided below.

Fluidic Components

The fluidic components of a flow cytometer require careful design considerations, as they can adversely impact cell phenotype and viability. This especially holds true when flowing large cellular aggregates that are more prone to shearing and clogging than single cells. The need for a gentle flow mechanism is also heightened by our long-term scientific goal of using the cells or cell aggregates for therapeutic use following imaging, assessment, and sorting. For this reason, the MPFC employs a horizontal flow cell made from PDMS microchannels plasma-bonded to a glass coverslip (Berthier & Beebe, 2007; Blake et al., 2007) (Fig. 2A,B). At the point of light interrogation, the chamber width of the flow cell is 5 mm, and the chamber height is 0.7 mm. Sample and sheath volumes were typically delivered using syringe pumps connected to the flow cell with Tygon tubing (0.1 cm I.D., 0.2 cm O.D.) at rates of 50–500 µL/min and 100–1,000 µL/min, respectively.

Optics Components

The MPFC system was built on an existing MPLSM platform designed for static (i.e., nonflow) imaging located in the Laboratory for Optical and Computational Instrumentation (LOCI), University of Wisconsin at Madison (White et al., 2001; Wokosin et al., 2003; Bird et al., 2004). While the MPLSM systems at LOCI have advanced instrumentation for spectral lifetime collection, adaptive optics, and SHG, the heart of the MPLSM system is a standard inverted microscope (Nikon TE2000, Melville, NY, USA) with Cambridge galvos (Cambridge Technology, Billerica, MA, USA) for scanning, Tsunami (Spectra Physics, Palo Alto, CA, USA) Ti:Sapphire laser, a Hamamatsu H7422 GaAsP photomultiplier detector (Hamamatsu Photonics, Bridgewater, NJ, USA) for fluorescence intensity detection and a sensitive silicon photodiode detector (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) for simultaneous transmission image collection. The purpose of detecting a transmitted image simultaneously has advantages inherent with collecting an image, namely, morphological analysis and detection of localized fluorescence within a multicellular entity. With no penalty in regard to acquisition speed or signal sensitivity, there was no reason not to collect a bright-field image in addition to the quantifiable fluorescence intensity image. The MPFC has been intentionally designed as a microscope stage insert such that it can readily be deployed on other MPLSMs including commercial systems.

Data Acquisition Components

The MPFC was designed to be a modular system that could interface with existing laser-scanning systems, either home built or commercially available. MPLSMs have extensive proprietary electronic and software scanning routines that would be expensive and unnecessary for the MPFC software to replicate. Instead, the MPFC software is built as a modular set of libraries that can be called by or interfaced with a commercial package. For our prototype system we used a laser scanning software package, WiscScan, developed at LOCI and deployed in a wide range of biological studies (Gill et al., 2003; Bird et al., 2005; Skala et al., 2007; Provenzano et al., 2008). While WiscScan does have some novel features that are particularly well suited for our application, the majority of the core acquisition functionality is representative of a commercial MPLSM package. Thus the WiscScan-MPFC integration is useful not only as a stand alone entity but also as a case study for deployment with other MPLSM control systems.

The majority of the MPFC features, such as simultaneous acquisition of transmitted images and multiphoton fluorescence data, image zoom, and integration (averaging) functionality, are standard components of any multiphoton system (including the LOCI instruments). The majority of the MPFC software development involved adding a real time quantitative readout of the flow stream on the MPFC for real-time morphology and intensity analysis. The MPFC departs from traditional flow cytometers in that an image is displayed in real time of the flow stream rather than a plot of the intensity alone. This is advantageous but a quantitative readout of the intensity and other particle properties is still needed. Rather than develop a proprietary solution for this, that is “hard coded” into WiscScan, we opted to develop an open source module for MPFC display and analysis that could interface with any MPLSM software package (using WiscScan as the test case). This module provides a real-time software analysis display so that when the multiphoton images are collected of the flow stream, a quantitative readout is displayed simultaneously. The open source ImageJ software package (National Institutes of Health) was chosen as the toolkit for this module development because this popular package already provided most of the functionality for this type of analysis and had the added advantage that any developed code could be run within WiscScan at runtime, or offline as a plug-in within ImageJ. Other analysis functionality, including existing flow cytometer analysis approaches from the community at large, can easily be added by using the same conduit and existing plug-in and macro functionality of ImageJ.

Instrument Validation

To validate the functionality of the MPFC design, we performed a variety of tests to examine the physical characteristics of the system as well as the applicability of the MPFC to assess fluorescence of large particles, namely fluorescent beads as a nonbiological standard and mouse embyroid bodies as an example of cell aggregates.

Control of Sample Stream Width via Hydrodynamic Focusing

Hydrodynamic focusing is the process by which two fluids under laminar flow and in common containment remain as separate streams based on differences in density, viscosity, the dimensions of the containment vessel, and/or velocity. This process is commonly used in flow cytometry to alter sample stream dimensions within a flow cell without constructing multiple flow cells of different dimensions. Here, a horizontal flow cell was microfabricated as described above. Sheath and sample fluids were delivered using syringe pumps connected to the flow cell with tygon tubing at rates of 100–1,000 µL/min and 50–500 µL/min, respectively.

To determine the range and variability of the sample streams possible in our flow cell, we modified the sheath to sample velocity ratio from 2 to 15 and measured the width of the resulting sample stream. The sample stream was distinguished from the flow stream by incorporating fluorescein into the sample fluid (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Movie 1).

Sample streams of 300–1,600 µm could be reliably achieved and precisely corresponded to modeled predictions (Lee et al., 2006) (Fig. 2D, R2 = 0.98).

Validation of Optical Acquisition Using Polystyrene Beads

Intensity image data acquired from a sample flowing through the MPFC system may vary from static measurements of the same sample if the data acquisition rate is slower than the sample speed per unit time or if the fluidic system mechanically disturbs the sample as it passes through the flow cell. To test the former, we introduced polystyrene beads of known diameter (100, 200, and 400 µm) into the MPFC system at maximum volumetric flow rate (300 µL/min, ratio of sheath to sample = 2) and measured the diameter of bright-field images of flowing beads. Increased bead dimensions would indicate an insufficient image capture speed. Using acquired bright-field images, we compared the average diameter of the flowing populations of beads to the average diameter of the same populations prior to introduction into the MPFC system. For all bead populations, the MPFC mean diameter (114 ± 9.2, 207 ± 8.9, and 408 ± 17.1) did not vary significantly from the static mean diameter (115 ± 6.4, 207 ± 8.6, and 402 ± 15.8: P = 0.69, P = 0.91, P = 0.08, respectively) (Fig. 3A – C).

Figure 3.

Size and intensity of fluorescent, polystyrene beads using the MPFC system. A: Accuracy and precision, using bright-field optics, of bead size using MPFC compared to bead size discerned using the MPLSM system without flow (i.e., static). Static measurements of bead diameter were made prior to introducing the beads into the MPFC system. Polystyrene beads were introduced into the MPFC at a maximum volumetric flow rate of 300 µL/min. Bead size measured under static conditions did not vary from bead size when measured on the MPFC system (P= 0.69, P= 0.91, P= 0.08). Standard deviation for each bead size measured on the MPFC was less than 8% of the total. B: Bright-field image of a 400 µm bead under static conditions. C: Bright-field image of a 400 µm bead using MPFC. Lack of warping and elongation indicate data acquisition rates were similar to the fluidic sample speed per unit time and that the microspheres experienced minimal mechanical disturbance. D: Relationship between bead diameter and normalized fluorescence intensity. Static measurements of mean bead intensity were made prior to measuring mean bead intensity using the MPFC system. Mean fluorescence intensity was plotted as a function of bead diameter. Best fit regression analysis was applied to the datasets and both static and MPFC conditions yielded second-order exponential relationships; R2 values of 0.99 and 0.99, respectively. E: Fluorescence intensity image of a 400 µm bead (same bead as B) under static conditions. Static images were captured at the location corresponding to the maximum total intensity, thus the “center” of the bead. F: Fluorescence intensity image of a 400 µm bead using MPFC (same bead as C). Mean fluorescence intensity did not vary between static and MPFC acquisition modes for each bead size (P= 0.58, P= 0.72, P= 0.74). a.i.u, arbitrary intensity units. Scale bar, 200 µm.

To further confirm that the electronics and data acquisition system provided appropriate acquisition speed to accommodate the maximum flow of the MPFC system (and to ensure events are not missed), we measured the mean intensity of individual polystyrene beads labeled with fluorescein. As before, polystyrene beads of known diameter (100, 200, and 400 µm) were introduced into the MPFC system at maximum volumetric flow rate (300 µL/min, ratio of sheath to sample = 2), and the mean intensity of flowing beads was determined. The mean intensity values of the flowing populations were compared to the mean intensity values of the centermost plane of the same populations prior to introduction into the MPFC system. For all bead populations (100, 200, and 400 µm), the MPFC normalized fluorescence measurements (8.1 ± 1.3, 19.4 ± 3.8, and 100 ± 18.6) did not vary significantly from the static normalized fluorescence measurements (7.7 ± 1.3, 19.4 ± 4.5, and 100 ± 16.7, P = 0.58, P = 0.72, P = 0.74) (Fig. 3D,E; Supplementary Movie 2).

The fact that intensity values in the flow system did not differ from those in static images indicates sufficient image capture speed. In addition, these results suggest there is limited sample movement within the Z focal plane during fluidic delivery.

Validation of Detection Depth

To determine whether the MPFC system was capable of generating information related to the interior portion of large entities by deep optical assessment, we mapped the mean fluorescence intensity as a function of bead size using the data obtained above. If detection of fluorescence in the interior of the microsphere were possible, one would expect an exponential trend between the size of the fluorescent sphere and the emitted fluorescent signal, by capturing a true representative cross-sectional area, and not simply surface fluorescence. One of the unique aspects of multiphoton fluorescence excitation is its ability to probe deep into tissue sections, which can be attributed to the fact that light scatter varies as an inverse function of wavelength. As a result, the infrared light used in MPFC obtains much higher depths of penetration than single photon excitation. Other commercial flow systems with fluidics capable of handling large particles cannot detect fluorescence in the interior of large entities (Fernandez et al., 2005) and so the relationship between size and fluorescence would be linear. These results indicated that the commercial systems are able to assess light emission corresponding to cross-sectional circumference and not cross-sectional surface area. When conducted with the MPFC, an exponential relationship was observed (Fig. 3D), confirming the ability of the system to noninva-sively probe the interior of large entities in an enhanced-throughput manner.

Assessment of Biological Applicability

Capacity of the MPFC to Analyze Stem Cell Aggregates

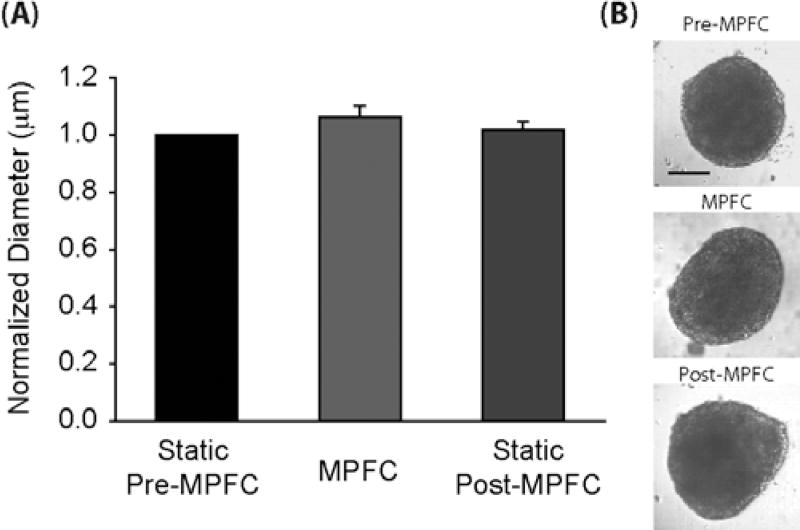

Cells are dynamic entities that are susceptible to mechanical forces and so the analysis of cells in the MPFC may differ dramatically from that of polymer beads. For example, cells are impacted by shear forces generated as a consequence of flow. Multicellular aggregates are particularly susceptible as intercellular connections can be disrupted by forces of (0.6 µdynes/connection or approximately 6 µdynes/cell (Haussinger et al., 2004; Bayas et al., 2006). If such connections are disrupted, biologic activity and ultimately therapeutic utility might be compromised. Thus, the MPFC system was designed to reduce shear forces to less than or equal to 0.6 µdynes/cell. In addition, cells, especially stem cells, express many cellular and extracellular binding receptors (i.e., cadherins, integrins) that can make them “sticky” as they are transported through the flow system. To determine whether stem cell aggregates would be mechanically disrupted using the MPFC system, we generated mouse embryoid bodies (EB), aggregates of ESCs that are undergoing differentiation, and measured the diameter of each EB before, during, and after introduction into the MPFC system. EBs used in these studies were 8–12 days old. Because EBs can vary in size due to variation in seeding density, time in suspension, and user technique, the measured diameter was normalized to the mean diameter of EB populations on each day of analysis (Fig. 4). The normalized size distribution did not vary significantly for EBs analyzed during (1.06 6 0.04, P = 0.05) or after flow (1.02 6 0.03 P = 0.29) when compared to EBs analyzed prior to introduction into the MPFC system. Standard deviation for EB size was less than 13% of the total size, indicating high precision of the MPFC system given the biologic nature of the samples. In addition, bright-field images were examined for evidence of frayed (disrupted) cell aggregates. The mean fraction of EBs exhibiting fraying or loss of a defined border affecting at least 25% of the perimeter was slightly higher in samples examined post-MPFC compare to samples examined pre-MPFC (13% × 12%, pre-MPFC, n = 177 and 25% × 12%, post-MPFC, n = 171, in five trials), but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.18). Thus, the composition of the fluidics system inflicts minimal mechanical disruption to these multicellular entities.

Figure 4.

Size of EBs using the MPFC system. A: Accuracy and precision of EB size using MPFC compared to EB size discerned using the MPLSM system without flow (i.e., static). Measurements of EB size, using bright-field optics, were made prior, during, and following introduction of the EBs into the MPFC system. Standard deviation for EB size was less than 13% of the total size. EB size discerned under static conditions after MPFC did not vary from EB size discerned using the MPFC system [P= 0.05 (pre versus MPFC), P= 0.29 (pre versus post), P= 0.13 (flow versus post)]. EBs were introduced into the MPFC at a volumetric flow rate of 200 µL/ min, which remained consistent between experiments. B: Bright-field images of pre-MPFC static, MPFC, and post-MPFC static EBs. Multicellular aggregates maintained original morphology and defined peripheral border during and after analysis with MPFC. Scale bar, 200 µm.

Analysis of Extrinsic Fluorescence of Multicellular Aggregates via MPFC

One of the primary challenges of stem cell research and clinical application is the generation of purified, mature cell types after differentiation. To this end, many researchers have established reporter stem cell lines coupled to lineage-specific promoters. While exceedingly valuable, lacking is the ability to detect these reporters in multicellular aggregates (including EBs) in an enhanced-throughput manner and to sort based on this detection. The MPFC system has the potential to address this need. To determine whether extrinsic fluorescent reporters of stem cell differentiation could be detected in EBs, mean fluorescence intensity of α-MHC::GFP transfected EBs and nontransfected EBs was determined using the MPFC. Alpha-MHC expression in this case indicates differentiation of a subset of ESCs to spontaneously contracting cardiomyocytes. Using the culture protocol described in the Materials and Methods section, an estimated 30–70% of EBs undergo cardiac differentiation and so will contain GFP+ regions (data not shown). GFP fluorescence was detected with the laser set for 890 nm excitation wavelength and a 520/35 band-pass emission filter. Mean fluorescence intensity of transfected EBs did not differ significantly before, during, or after MPFC [46.1 ± 24.6, 42.5 ± 24.7, 39.6 ± 29.3 respectively, P = 0.47 (pre versus MPFC), P = 0.24 (pre versus post), P = 0.60 (MPFC versus post) Fig. 5, Supplementary Movie 3].

Figure 5.

(Color online) Extrinsic fluorescence intensity of EBs using the MPFC system. The Ti-Sapphire laser was tuned to 890 nm to excite GFP and a 520/35 band-pass emission filter was used to exclude autofluorescence. A nontransfected mESC cell line (D3) and an α-MHC::GFP transfected mESC cell line were used to generate EBs. Histogram analysis of GFP expression of EBs (A) pre-MPFC, (B) MPFC, and (C) post-MPFC. Two separate experiments were conducted and approximately 50 EBs were analyzed per condition (i.e., before, during, and after MPFC). The maximum background intensity was defined such that 95% of the nontransfected EBs expressed mean fluorescence intensity levels below this intensity level (line in histogram). The percentage shown, indicating the fraction of EBs derived from transfected cells expressing GFP, was determined based on the background level. Representative images of D3 and α-MHC::GFP mESC-derived EBs, located directly adjacent to the corresponding plot, are provided for each condition. Color bar represents quantified intensity levels from 0 (black) to 255 (green). a.i.u., arbitrary intensity units. Scale bar, 200 µm.

In addition, the data were analyzed to determine whether the GFP+ fraction detected with MPFC corresponded to that detected using static MPLSM. To this end, a gate based on mean fluorescence intensity was established to exclude ∼95% of nontransfected EBs; thus events exceeding the mean fluorescence intensity of the gate value (dotted vertical line on histogram plots, Fig. 5) were deemed GFP+. The fraction of GFP+ events of the EBs from the α-MHC::GFP line, pre-MPFC, MPFC, and post-MPFC were 66%, 60%, and 46%, respectively (Fig. 5). The post-MPFC fraction is substantially less that the pre-MPFC and MPFC values and likely reflects the suboptimal conditions in which the EBs were maintained after flow. These conditions include diluted media as a consequence of merging sheath and sample streams in the collection vessel and uncontrolled temperature and gas exposure in the collection vessel. The similarity in proportion of detected fluorescent aggregates between the pre-MPFC and during MPFC conditions indicates that extrinsic fluorescence of stem cell aggregates can be reliably detected by the MPFC system in an enhanced throughput manner. Future adaptations to incorporate a sterile sorting mechanism with controlled nutrient, temperature, and gas exposure will prove very useful for the generation of mature cell types for analytical study and clinical application.

Analysis of Intrinsic Fluorescence of Stem Cell-Derived EBs via MPFC

Continued advances in stem cell research and clinical application depend on the discovery of noninvasive endogenous biomarkers (as opposed to extrinsic, invasive markers, including the GFP reporter system described above) to discern stem cell status and differentiation state at both the single cell and 3D (i.e., cell aggregate or tissue construct) level and to sort populations based on this assessment. Multiphoton fluorescence excitation based approaches have been shown to be able to detect differences in the intensity of intrinsic fluorescence between cells in different functional states (Kirkpatrick et al., 2007; Provenzano et al., 2008; Conklin et al., 2009), including between stem cells and mature cells (Guo et al., 2008; Uchugonova & Konig, 2008). So, in principle, the MPFC system should be capable of the same in enhanced throughput. To test this possibility, we introduced 8–12 day EBs into the MPFC system and probed for intrinsic fluorescence, most likely from NADH, using 780 nm two-photon excitation. Mean fluorescence intensity was determined for EBs in this context before, during, and after MPFC analysis. Mean intrinsic fluorescence did not vary between conditions [91.8 ± 35.0, 86.8 ± 36.7, and 85.2 ± 34.7, respectively: P = 0.55 (pre versus MPFC), P = 0.46 (pre versus post), P = 0.89 (MPFC versus post); Fig. 6A, Supplementary Movie 4]; however, the standard deviation was substantially high.

Figure 6.

Intrinsic fluorescence intensity of EBs using the MPFC system. The Ti:Sapphire laser was tuned to 780 nm to excite the intrinsic fluorescent metabolite, NADH. A: Mean fluorescence intensity of EBs before, during, and after analysis with the MPFC system. Mean fluorescence intensity of EBs did not vary between acquisition conditions [P = 0.55 (pre versus MPFC), P= 0.46 (pre versus post), P= 0.89 (flow versus post)]. B: NADH fluorescence intensity distributions before, during, and after analysis. Standard deviations within each condition described in panel A were large, and so the distribution of intensity between samples was compared. Though the distribution was large, the distribution profile did not vary substantially between conditions. C: Representative images depict NADH intensity acquired pre-MPFC, MPFC, and post-MPFC. Localized differences in intrinsic fluorescence were detected in all three conditions. The color bar represents quantified intensity levels from 0 (black) to 255 (white). a.i.u., arbitrary intensity units. Scale bar, 200 µm.

Variation was not a consequence of manipulation or an artifact of the MPFC system as the intensity distribution was similar for all conditions (Fig. 6B). Indeed, high variability was anticipated as EBs cultured in this manner begin maturation in an uncontrolled temporal and spatial fashion and therefore would be expected to elicit different metabolic demands depending on the phase of development. It is precisely these differences that we hope to capitalize upon to employ intrinsic fluorescence as an indicator of stem cell health and differentiation status.

Determination of Particle Recovery on MPFC

Populations of cells, especially populations of stem cells, can be rare; therefore, efficient recovery of cell populations after live cell analysis is important. To test the recovery rate for the MPFC, we suspended a known concentration of either polystyrene beads (100, 200, and 400 µm) or multicellular aggregates (EBs) and introduced them into the MPFC for a specified amount of time. The number of particles that passed through the system to the waste reservoir was recorded (i.e., “output”) and reported as a fraction of the total particle number ejected from the sample syringe (i.e., “input”; Fig. 7). The final results were normalized to the mean input particle count for each type of large particle. The 200 and 400 µm beads as well as the EBs had normalized particle counts of greater than or equal to 81% of the respective input values. In contrast, recovery of the 100 µm beads was actually higher than the input values (> 100%). Variability between samples can be attributed to a lack of uniform particle delivery from of the sample syringe. Despite the incorporation of a stirring mechanism in the sample reservoir, particles tend to settle in the sample reservoir, and so the concentration of particles can increase during the duration of sample injection. Future generations of the MPFC system will include an improved mechanism for delivery and maintenance of samples containing a uniform suspension of particles. Despite this difficulty, no significant clogging or variations in pressure were observed in the system.

Figure 7.

Particle recovery following MPFC acquisition. Polystyrene beads or EBs were introduced into the MPFC system and the relative fraction recovered post-MPFC was determined. Input (concentration introduced into the system, black bars) was compared to output (concentration acquired in the waste reservoir after MPFC analysis, gray bars) for beads and EBs. Particle recovery exceeding 100% likely reflects an increase in concentration of particles in the syringe prior to introduction into the system and thus the subsequent measurement of a concentrated sample. Minimum particle recovery was 81%.

Discussion

Motivated by the unique challenges of studying stem cells, we generated and validated a proof-of-concept MPFC instrument, capable of accurate, noninvasive, and enhanced-throughput optical analyses of living single cells and multicellular aggregates or bioengineered constructs. The instrument is composed of a flow cell through which large particles stream past a light interrogation point, an optics system with simultaneous transmitted and multiphoton excitation capability and data acquisition software to provide real-time qualitative and quantitative readout data. In this first study with the MPFC, we focused on analysis of stem cells; however, the system is equally capable of analyzing other cell types including pancreatic islets and lymphoblastoid cell lines (data not shown). The components of the system were explicitly designed to garner easy access to the system by both research and clinical laboratories. We have confirmed the integrity of a range of widths (300–1,600 µm) of the sample stream, particle recovery, speed of image capture, and accuracy of image capture. In addition, we show reliable determination of expression of GFP, a fluorophore extrinsically incorporated into the cell genome and intrinsic fluorescence, most likely representing NADH, a key metabolic intermediate. Future studies will continue to explore intrinsic fluorescence in order to validate the potential of intrinsic fluorophores to serve as biomarkers for flow cytometry.

We have shown that the MPFC system can detect extrinsic fluorescence deep in the interior of beads and cell aggregates. This ability is particularly useful for stem cell research because one of the primary challenges of the field is the generation of purified, mature cell types after differentiation in a 3D organization, whether that be part of a multicellular EB or part of 3D constructs, such as polymer and extracellular matrix-based substrates of a bioengineered tissue construct. To this end, many have established reporter stem cell lines coupled to lineage-specific promoters. While exceedingly valuable, lacking is the ability to detect these reporters in the culture modalities currently used to most efficiently generate differentiated cells because traditional sorting techniques rely on single cell methodologies. Removal of cells from the culture modalities for traditional analyses is known to alter cell fate (Evseenko et al., 2009; Gong et al., 2008; Zhong et al., 2008); thus, a system such as the MPFC system, which can optically characterize the cells prior to removal, is a substantial advance. Here we show that extrinsic fluorescent reporters of cardiac differentiation of ESCs can be detected within EBs. The noninvasive depth of penetration and excellent signal-to-noise signal afforded by multiphoton excitation yields fluorescence images that are more representative of the entire EB than those obtained with standard epifluorescence microscopy. The MPFC retains the 3D benefits of MPLSM and harnesses this in a flow context.

We have characterized the functionality of the MPFC and its applicability to flow analysis of cellular aggregates. The biomedical and clinical application of the MPFC system will be significantly enhanced by the added capacity to sort cells and multicellular entities based on optical properties discerned by the system. For example, EBs expressing lineage-specific reporters (as described above) at high levels could be purified from their counterparts. Molecular profiling could then be conducted on the purified population to discern altered gene and protein expression levels, which could be further employed to better understand stem cell biology, and, more practically, to develop better means to efficiently induce and control stem cell differentiation. Several different sorting mechanisms have been incorporated into microfluidic devices similar to the one used for the MPFC system. For example, optical force switching has been used, wherein optical repulsion force, originating from the radiation pressure of a focused laser beam is used to deflect the cell to the desired output channel (Wang et al., 2005). As another example, valve switching has been used, wherein pressurized gases, vacuum, or syringe pump are used to actuate the closing and opening of valves for sorting (Zhang et al., 2002; Wolff et al., 2003). Finally, electrokinetic switching has been used, wherein dielectrophoretic force is used to deflect a target particle (Fu et al., 1999; Dittrich & Schwille, 2003). Each method suffers at least one significant limitation: optical force switching cannot accomplish multi-parametric sorting, valve switching requires bulky and onerous pumps and tubing, and electrokinetic switching requires complex fabrication to insert the microelectrodes. In an effort to address these limitations, and in keeping with our desire to ensure accessibility, we have begun to develop a sorting device that relies on passive pumping in an effort to divert individual particles to sorting chambers defined by the operator (Pearce et al., 2005; Berthier & Beebe, 2007). Passive pumping harnesses the higher internal pressure of smaller drops of liquid compared to larger drops to perform useful work (i.e., to drive or pump fluid through a channel) and can be executed with a standard pipettor common to most laboratories.

In addition to the planned sorting mechanism developments, we have begun to appreciate the need to focus the sample stream both laterally and vertically. Currently, we are able to analyze uniformly sized beads and multicellular aggregate populations with relatively low standard deviations in the context of flow. The ability to focus the sample stream laterally and vertically will allow us to more accurately probe the center of large particles, especially for populations that vary more significantly in size (Yang et al., 2005; Cho et al., 2006; Simonnet & Groisman, 2006; Howell et al., 2008; Mao et al., 2009).

Further biomedical and clinical use of the MPFC will necessitate additional development of applications and the corresponding technology to accurately and robustly detect and establish biomarkers for stem cell differentiation and other key cellular events. While the described MPFC and the proposed sorting technologies represent primary components toward this goal, a corresponding experimental effort to define optical biomarkers for the MPFC is needed. While many groups have noted the potential of intrinsic fluorophores such as a FAD and NADH for disease progression characterization, in particular, in cancer studies (Kirkpatrick et al., 2007; Provenzano et al., 2008; Conklin et al., 2009), these fluorophores are still far from being considered a true biomarker by the medical establishment. To be considered a true biomarker, endogenous fluorophores need to be robustly and accurately assayed in a heterogeneous environment with appropriate control for false-positives and clear diagnostic linkage. Further studies with MPLSM and the MPFC in different stem cell models and stages of differentiation with NADH and FAD detection are needed to determine the diagnostic staging and predictive nature of these intrinsic fluorophores. As well, additional fluorophores such as collagen (Dayan et al., 1994; Banerjee et al., 1999; Gill et al., 2003) and tryptophan (Diagaradjane et al., 2005; Laiho et al., 2005) are of interest and can be characterized.

While much of the characterization of the fluorophores toward the goal of defining a true biomarker can be done with the current MPFC prototype, it is clear that additional technology improvements could improve the MPFC’s ability to detect these fluorophores in 3D assays in enhanced-throughput. Preliminary data for the MPFC demonstrated that the speed of conventional MPLSM electronics is sufficient to drive the MPFC and gather extrinsic and intrinsic intensity data. However, it is clear that additional speed would have several advantages, including faster collection times with more assayed components and, importantly, the ability to integrate (frame average) further and enhance signal. Approaches used in the neuroscience community (Beurg et al., 2009) for fast calcium imaging and other dynamic event imaging could be utilized in the MPFC. These include fast acquisition approaches in MPLSM hardware, such as acoustic based optical scanning, and software-based approaches, such as line scanning. There is a growing body of evidence that, in addition to intensity, there are other properties of fluorescence, such as the spectra (Lakowicz, 1999), the fluorescence lifetime (Lakowicz et al., 1992; Lakowicz, 1999), and polarization state (Suhling et al., 2005), which could be used for characterization of a disease state or cellular phenomena. For example, several papers have shown the potential of spectral and lifetime approaches for accurate metabolic mapping and examination of the redox ratio in breast cancer (Bird et al., 2005; Skala et al., 2005, 2007; Conklin et al., 2009). The optical platform on which the MPFC is interfaced already has the capability for spectral and lifetime detection in static mode; the major hurdle for deploying these technologies in flow mode has to do with speed of collection. There are efforts underway by several groups to develop electronics for faster photon counting that could be used for faster lifetime collection in a MPFC context.

The current MPFC can uniquely assay intrinsic and extrinsic fluorescence as potential markers for differentiation deep within intact 3D stem cell models. While further work is needed to refine this system for speed and accuracy as well as to develop sorting based on these markers, the MPFC already represents a major advance in biomedical research based on its current ability to detect fluorescence changes deep within the interior of stem cell aggregates. As described, the MPFC prototype is being used to assay em-bryoid bodies, and this characterization work is not only advancing the instrument and helping refine it but is also demonstrating the current research utility for stem cell biology. Of course, the instrument could also be applied to benefit many other research fields. For example, the MPFC system might be used to detect presumed cancer stem cells within tumor cell aggregates or tissue biopsies using the aldehyde dehydrogenase reporter system (Chen et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2009; Jiang et al., 2009; Tanei et al., 2009). With additional tests and the successful addition of the described sorting mechanism, there is great potential of the MPFC in the clinic for cellular transplantation (including stem cells, pancreatic islets, or other somatic cells). Such a clinical MPFC could be used to quickly and accurately determine which cells are most appropriate for a given clinical application and then directly use that proven characterized subpopulation (post-sorting) for human transplant. If such a device is realized, not only will currently available clinical transplantation approaches benefit, but also significant new transplantations will be enabled as the stage and quality of cells for transplant could be determined and improved.

Supplementary Material

A supplementary movie available online shows altering sample flow rate to vary stream widths. Please visit journal.cambridge.org/jid_MAM.

A supplementary movie available online shows fluorescent beads flowing through the MPFC. Please visit journal. cambridge.org/jid_MAM.

A supplementary movie available online shows EBs expressing α-MHC::GFP flowing through the MPFC. Please visit journal.cambridge.org/jid_MAM.

A supplementary movie available online shows intrinsic fluorescence of D3 EBs flowing through the MPFC. Please visit journal.cambridge.org/jid_MAM.

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthew Hanson and Luis Fernandez for important conversations related to the limitations of current flow cytometry systems for large particle analysis. We thank the Kamp Lab (Department of Medicine), the Williams Lab (Department of Biomedical Engineering), LOCI, Rupa Shevde (WiCell), Tracy Drier (Department of Chemistry), Peter Crump (College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Computing and Biometry facility), Gary Hammersley (Labora-tory of Molecular Biology), Christopher Westphal, Alex Blake, and Timothy Pearce (Department of Biomedical Engineering) for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL092218), the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation, and the University of Wisconsin, Industrial & Economic Development Research (IEDR) Program.

References

- Banerjee B, Miedema BE, Chandrasekhar HR. Role of basement membrane collagen and elastin in the auto-fluorescence spectra of the colon. J Investig Med. 1999;47(6):326–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayas MV, Leung A, Evans E, Leckband D. Lifetime measurements reveal kinetic differences between homophilic cadherin bonds. Biophys J. 2006;90(4):1385–1395. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.069583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenky P, Bogan KL, Brenner C. NAD+ metabolism in health and disease. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32(1):12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L. Biochemistry. New York: W.H. Freeman; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Berthier E, Beebe DJ. Flow rate analysis of a surface tension driven passive micropump. Lab Chip. 2007;7(11):1475–1478. doi: 10.1039/b707637a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurg M, Fettiplace R, Nam J-H, Ricci AJ. Localization of inner hair cell mechanotransducer channels using high-speed calcium imaging. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(5):553–558. doi: 10.1038/nn.2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird DK, Eliceiri KW, Fan CH, White JG. Simultaneous two-photon spectral and lifetime fluorescence microscopy. Appl Opt. 2004;43(27):5173–5182. doi: 10.1364/ao.43.005173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird DK, Yan L, Vrotsos KM, Eliceiri KW, Vaughan EM, Keely PJ, White JG, Ramanujam N. Metabolic mapping of MCF10A human breast cells via multiphoton fluorescence lifetime imaging of the coenzyme NADH. Cancer Res. 2005;65(19):8766–8773. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake AJ, Pearce TM, Rao NS, Johnson SM, Williams JC. Multilayer PDMS microfluidic chamber for controlling brain slice microenvironment. Lab Chip. 2007;7(7):842–849. doi: 10.1039/b704754a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blinova K, Carroll S, Bose S, Smirnov AV, Harvey JJ, Knutson JR, Balaban RS. Distribution of mitochondrial NADH fluorescence lifetimes: Steady-state kinetics of matrix NADH interactions. Biochemi. 2005;44(7):2585–2594. doi: 10.1021/bi0485124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagnola PJ, Loew LM. Second-harmonic imaging microscopy for visualizing biomolecular arrays in cells, tissues and organisms. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(11):1356–1360. doi: 10.1038/nbt894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagnola PJ, Millard AC, Terasaki M, Hoppe PE, Malone CJ, Mohler WA. Three-dimensional high-resolution second-harmonic generation imaging of endogenous structural proteins in biological tissues. Biophys J. 2002;82(1 Pt 1):493–508. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75414-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenedo RL, Bratt-Leal AM, Marklein RA, Seaman SA, Bowen NJ, McDonald JF, McDevitt TC. Homogeneous and organized differentiation within embryoid bodies induced by microsphere-mediated delivery of small molecules. Biomaterials. 2009;30(13):2507–2515. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centonze VE, White JG. Multiphoton excitation provides optical sections from deeper within scattering specimens than confocal imaging. Biophys J. 1998;75(4):2015–2024. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77643-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B, Legallais V, Schoener B. Metabolically linked changes in fluorescence emission spectra of cortex of rat brain, kidney and adrenal gland. Nature. 1962;195:1073–1075. doi: 10.1038/1951073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YC, Chen YW, Hsu HS, Tseng LM, Huang PI, Lu KH, Chen DT, Tai LK, Yung MC, Chang SC, Ku HH, Chiou SH, Lo WL. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a putative marker for cancer stem cells in head and neck squa-mous cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385(3):307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YM, Kwon S, Pak YK, Seol HW, Choi YM, Park Do J, Park KS, Lee HK. Dynamic changes in mito-chondrial biogenesis and antioxidant enzymes during the spontaneous differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;348(4):1472–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins TJ. ImageJ for microscopy. BioTechniques. 2007;43(S1):25–30. doi: 10.2144/000112517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin MW, Provenzano PP, Eliceiri KW, Sullivan R, Keely PJ. Fluorescence lifetime imaging of endogenous fluorophores in histopathology sections reveals differences between normal and tumor epithelium in carcinoma in situ of the breast. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2009;53(3):145–157. doi: 10.1007/s12013-009-9046-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan D, Wolman M, Hammel I. Histochemical study of the blue autofluorescence of collagen in oral irritation fibroma: Effects of age of patients and of the duration of lesions. Histol Histopathol. 1994;9(1):11–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk W, Strickler JH, Webb WW. Two-photon laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. Science. 1990;248(4951):73–76. doi: 10.1126/science.2321027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagaradjane P, Yaseen MA, Yu J, Wong MS, Anvari B. Autofluorescence characterization for the early diagnosis of neoplastic changes in DMBA/TPA-induced mouse skin carcinogenesis. Lasers Surg Med. 2005;37(5):382–395. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaspro A. Two-photon excitation. A new potential perspective in flow cytometry. Minerva Biotechnol. 1999;11:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich PS, Schwille P. An integrated microfluidic system for reaction, high-sensitivity detection, and sorting of fluorescent cells and particles. Anal Chem. 2003;75(21):5767–5774. doi: 10.1021/ac034568c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elknerova K, Lacinova Z, Soucek J, Marinov I, Stock-bauer P. Growth inhibitory effect of the antibody to hematopoietic stem cell antigen CD34 in leukemic cell lines. Neoplasma. 2007;54(4):311–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evseenko D, Schenke-Layland K, Dravid G, Zhu Y, Hao QL, Scholes J, Chao X, Maclellan WR, Crooks GM. Identification of the critical extracellular matrix proteins that promote human embryonic stem cell assembly. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18(6):919–928. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez LA, Hatch EW, Armann B, Odorico JS, Hul-lett DA, Sollinger HW, Hanson MS. Validation of large particle flow cytometry for the analysis and sorting of intact pancreatic islets. Transplantation. 2005;80(6):729–737. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000179105.95770.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fijnvandraat AC, van Ginneken AC, Schumacher CA, Boheler KR, Lekanne Deprez RH, Christoffels VM, Moorman AF. Cardiomyocytes purified from differentiated embryonic stem cells exhibit characteristics of early chamber myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35(12):1461–1472. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu AY, Spence C, Scherer A, Arnold FH, Quake SR. A microfabricated fluorescence-activated cell sorter. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17(11):1109–1111. doi: 10.1038/15095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill EM, Malpica A, Alford RE, Nath AR, Follen M, Richards-Kortum RR, Ramanujam N. Relationship between collagen autofluorescence of the human cervix and menopausal status. Photochem Photobiol. 2003;77(6):653–658. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2003)077<0653:rbcaot>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J, Sagiv O, Cai H, Tsang SH, Del Priore LV. Effects of extracellular matrix and neighboring cells on induction of human embryonic stem cells into retinal or retinal pigment epithelial progenitors. Exp Eye Res. 2008;86(6):957–65. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo HW, Chen CT, Wei YH, Lee OK, Gukassyan V, Kao F, J, Wang HW. Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide fluorescence lifetime separates human mesenchy-mal stem cells from differentiated progenies. J Biomed Opt. 2008;13(5):050505. doi: 10.1117/1.2990752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanninen PE, Soini JT, Soini E. Photon-burst analysis in two-photon fluorescence excitation flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1999;36(3):183–188. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19990701)36:3<183::aid-cyto6>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubert K, Drier T, Beebe D. PDMS bonding by means of a portable, low-cost corona system. Lab Chip. 2006;6(12):1548–1549. doi: 10.1039/b610567j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haussinger D, Ahrens T, Aberle T, Engel J, Stetefeld J, Grzesiek S. Proteolytic E-cadherin activation followed by solution NMR and X-ray crystallography. EMBO J. 2004;23(8):1699–1708. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell PB, Jr, Golden JP, Hilliard LR, Erickson JS, Mott DR, Ligler FS. Two simple and rugged designs for creating microfluidic sheath flow. Lab Chip. 2008;8(7):1097–1103. doi: 10.1039/b719381e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang EH, Hynes MJ, Zhang T, Ginestier C, Dontu G, Appelman H, Fields JZ, Wicha MS, Boman BM. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a marker for normal and malignant human colonic stem cells (SC) and tracks SC overpopulation during colon tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69(8):3382–3389. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh D, Gu W, Kamotani Y, Grotberg JB, Takayama S. Microfluidics for flow cytometric analysis of cells and particles. Physiol Meas. 2005;26(3):R73–R98. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/26/3/R02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Qiu Q, Khanna A, Todd NW, Deepak J, Xing L, Wang H, Liu Z, Su Y, Stass SA, Katz RL. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a tumor stem cell-associated marker in lung cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7(3):330–338. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajiwara K, Kamamoto M, Ogata S, Tanihara M. A synthetic peptide corresponding to residues 301–320 of human Wnt-1 promotes PC12 cell adhesion and hippocampal neural stem cell differentiation. Peptides. 2008;29(9):1479–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick ND, Brewer MA, Utzinger U. Endogenous optical biomarkers of ovarian cancer evaluated with multiphoton microscopy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(10):2048–2057. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laiho LH, Pelet S, Hancewicz TM, Kaplan PD, So PT. Two-photon 3-D mapping of ex vivo human skin endogenous fluorescence species based on fluorescence emission spectra. J Biomed Opt. 2005;10(2):024016. doi: 10.1117/1.1891370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz JR. Principals of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. New York: Academic Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz JR, Szmacinski H, Nowaczyk K, Johnson ML. Fluorescence lifetime imaging of free and protein-bound NADH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(4):1271–1275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G, Chang C, Huang S, Yang R. The hydro-dynamic focusing effect inside rectangular microchannels. J Micromech Microeng. 2006;16:1024–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Leong DT, Nah WK, Gupta A, Hutmacher DW, Woodruff MA. The osteogenic differentiation of adipose tissue-derived precursor cells in a 3D scaffold/matrix environment. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2008;5(4):319–327. doi: 10.2174/157016308786733537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltsev VA, Rohwedel J, Hescheler J, Wobus AM. Embryonic stem cells differentiate in vitro into cardio-myocytes representing sinusnodal, atrial and ventricular cell types. Mech Dev. 1993;44(1):41–50. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(93)90015-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, Lin SC, Dong C, Huang TJ. Single-layer planar on-chip flow cytometer using microfluidic drifting based three-dimensional (3D) hydrodynamic focusing. Lab Chip. 2009;9(11):1583–1589. doi: 10.1039/b820138b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Fernandez S, Hernandez-Torres F, Franco D, Lyons GE, Navarro F, Aranega AE. Pitx2c overexpression promotes cell proliferation and arrests differentiation in myoblasts. Dev Dyn. 2006;235(11):2930–2939. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Hance WC, LaCorbiere M, Fuller SJ, Evans SM, Lyons G, Schmidt C, Robbins J, Chien KR. In vitro chamber specification during embryonic stem cell cardio-genesis. Expression of the ventricular myosin light chain-2 gene is independent of heart tube formation. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(33):25244–25252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappajohn DJ, Penneys R, Chance B. NADH spec-trofluorometry of rat skin. J Appl Physiol. 1972;33(5):684–687. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.33.5.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce TM, Williams JJ, Kruzel SP, Gidden MJ, Williams JC. Dynamic control of extracellular environment in in vitro neural recording systems. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehab Eng. 2005;13(2):207–212. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2005.848685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips BW, Horne R, Lay TS, Rust WL, Teck TT, Crook JM. Attachment and growth of human embryonic stem cells on microcarriers. J Biotechnol. 2008;138(1–2):24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2008.07.1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzano PP, Rueden CT, Trier SM, Yan L, Ponik SM, Inman DR, Keely PJ, Eliceiri KW. Nonlinear optical imaging and spectral-lifetime computational analysis of endogenous and exogenous fluorophores in breast cancer. J Biomed Opt. 2008;13(3):031220. doi: 10.1117/1.2940365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanujam N, Mitchell MF, Mahadevan-Jansen A, Thom-sen SL, Staerkel G, Malpica A, Wright T, Atkinson N, Richards-Kortum R. Cervical precancer detection using a multivariate statistical algorithm based on laser-induced fluorescence spectra at multiple excitation wavelengths. Photochem Photobiol. 1996;64(4):720–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1996.tb03130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes JM, Fermanian S, Yang F, Zhou SY, Herretes S, Murphy DB, Elisseeff JH, Chuck RS. Metabolic changes in mesenchymal stem cells in osteogenic medium measured by autofluorescence spectroscopy. Stem Cells. 2006;24(5):1213–1217. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonnet C, Groisman A. High-throughput and high-resolution flow cytometry in molded microfluidic devices. Anal Chem. 2006;78(16):5653–5663. doi: 10.1021/ac060340o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skala MC, Riching KM, Gendron-Fitzpatrick A, Eick-hoff J, Eliceiri KW, White JG, Ramanujam N. In vivo multiphoton microscopy of NADH and FAD redox states, fluorescence lifetimes, and cellular morphology in precancerous epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(49):19494–19499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708425104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skala MC, Squirrell JM, Vrotsos KM, Eickhoff JC, Gendron-Fitzpatrick A, Eliceiri KW, Ramanujam N. Multiphoton microscopy of endogenous fluorescence differentiates normal, precancerous, and cancerous squamous epithelial tissues. Cancer Res. 2005;65(4):1180–1186. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squirrell JM, Wokosin DL, White JG, Bavister BD. Long-term two-photon fluorescence imaging of mammalian embryos without compromising viability. Nat Biotech-nol. 1999;17(8):763–767. doi: 10.1038/11698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer VJ, Jameson R, Pellereau E, Pepin A, Chen Y. A microfluidic mammalian cell sorter based on fluorescence detection. Microelectr Eng. 2004;73:852–857. [Google Scholar]

- Suhling K, French PM, Phillips D. Time-resolved fluorescence microscopy. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2005;4(1):13–22. doi: 10.1039/b412924p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR, Johnson ML. Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy: Homodyne technique using high-speed gated image intensifier. Methods Enzymol. 1994;240:723–748. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)40069-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanei T, Morimoto K, Shimazu K, Kim SJ, Tanji Y, Tagu-chi T, Tamaki Y, Noguchi S. Association of breast cancer stem cells identified by aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 expression with resistance to sequential Paclitaxel and epirubicin-based chemotherapy for breast cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(12):4234–4241. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teisanu RM, Lagasse E, Whitesides JF, Stripp BR. Prospective isolation of bronchiolar stem cells based upon immunophenotypic and autofluorescence characteristics. Stem Cells. 2009;27(3):612–622. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchugonova A, Konig K. Two-photon autofluores-cence and second-harmonic imaging of adult stem cells. J Biomed Opt. 2008;13(5):054068. doi: 10.1117/1.3002370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]