Abstract

We report the synthesis, characterization, and reactivity of [LFe3(PhPz)3OMn(sPhIO)][OTf]x (3: x = 2; 4: x = 3), where 4 is one of very few examples of iodosobenzene–metal adducts characterized by X-ray crystallography. Access to these rare heterometallic clusters enabled differentiation of the metal centers involved in oxygen atom transfer (Mn) or redox modulation (Fe). Specifically, 57Fe Mössbauer and X-ray absorption spectroscopy provided unique insights into how changes in oxidation state (FeIII2FeIIMnII vs. FeIII3MnII) influence oxygen atom transfer in tetranuclear Fe3Mn clusters. In particular, a one-electron redox change at a distal metal site leads to a change in oxygen atom transfer reactivity by ca. two orders of magnitude.

Keywords: C–H bond oxygenation, clusters, iodosobenzene adduct, multimetallic complexes, oxygen atom transfer

Terminal metal-oxo moieties are commonly invoked in oxidative biological transformations.[1] Due to the important functions of reactive metal-oxo motifs in C–H bond functionalization and water oxidation, intense efforts have been made to develop synthetic model complexes to elucidate their behavior through structure–function studies.[2] Both the oxidation- and spin-state of the metal center affect their reactivity.[3] Nonetheless, studying these effects on C–H bond activation or oxygen atom transfer is challenging due to limitations in accessing metal complexes with properties suitable for meaningful comparison.[2d,4] Such studies are even more challenging in multinuclear systems, which represent more accurate models of enzymes’ active sites.[1f,5] Only recently, a study of bimetallic complexes demonstrated that changing the oxidation state from [HO-FeIV-O-FeIV=O] to [HO-FeIII-O-FeIV=O] resulted in a change in spin-state, concomitant with a remarkable million-fold increase in the rate of C–H bond cleavage.[6] Apart from bimetallic complexes, there are no other reports, to our knowledge, that examine the effect of remote redox changes on oxygen atom transfer (OAT) or C–H bond oxygenation.

Herein, we report on the synthesis and characterization of a new series of clusters, [LFe3(PhPz)3OMn][OTf]x (Figure 1; 1: x = 2; 2: x = 3), and demonstrate how changing the oxidation state (FeIII2FeIIMnII vs. FeIII3MnII) has profound effects on the rate of oxygen atom transfer from their corresponding iodosobenzene adducts [LFe3(PhPz)3OMn(sPhIO)][OTf]x (3: x = 2; and 4: x = 3). Compound 4 is stable for a few hours at room temperature (RT), and constitutes one of the very rare example of a iodosobenzene adduct characterized by X-ray crystallography.[7] Access to these heterometallic clusters enabled us to differentiate the Mn and Fe metal centers by both 57Fe Mössbauer and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), giving unique insights into the structure and reactivity of 3 and 4 where coordination of iodosobenzene to low-valent MnII is observed.

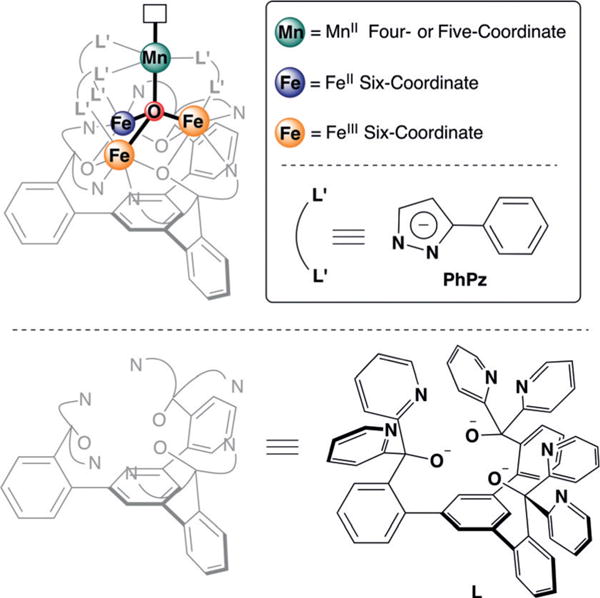

Figure 1.

General molecular structure of [LFe3(PhPz)3OMn]n+ 3 (n = 2–3; top left), supported by pyrazolates and a 1,3,5- triarylbenzene-based ligand. The inset shows the coloring scheme for the metal oxidation states.

Complexes [LFe3(PhPz)3OMn][OTf]2 (1) and [LFe3(PhPz)3OMn][OTf]3 (2; PhPz = phenylpyrazolate, OTf = trifluoromethanesulfonate) were prepared by modifying our recently reported literature procedure for [LFe3(PhPz)3OFe][OTf]2.[8] Both 1 and 2 were fully characterized by a wide variety of physical methods including 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figures S1 and S2 in the Supporting Information), X-ray crystallography (Figure 2, and Figures S20 and S21), Mössbauer spectroscopy (Figure S17), and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (Figures S12–S14).

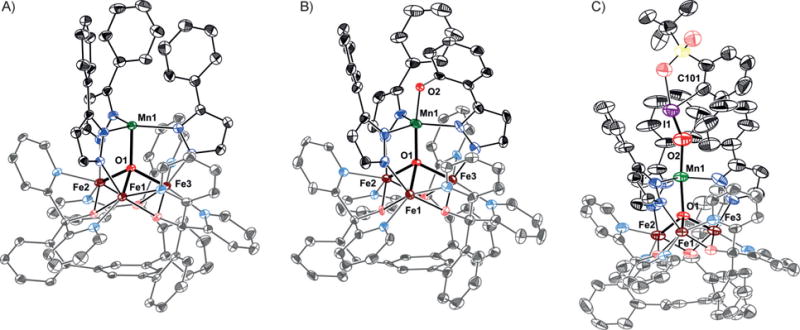

Figure 2.

Crystals structures of A) [LFe3(PhPz)3OMn][OTf]2 (1); B) [LFe3(PhPz)2(OArPz)OMn][OTf]2 (5); and C) [LFe3(PhPz)3OMn(sPhIO)][OTf]3 (4). Thermal ellipsoids are shown at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms, outer-sphere counter ions, and co-crystallized solvent molecules are not shown for clarity. See Table S1 for a summary of selected bond lengths and angles.

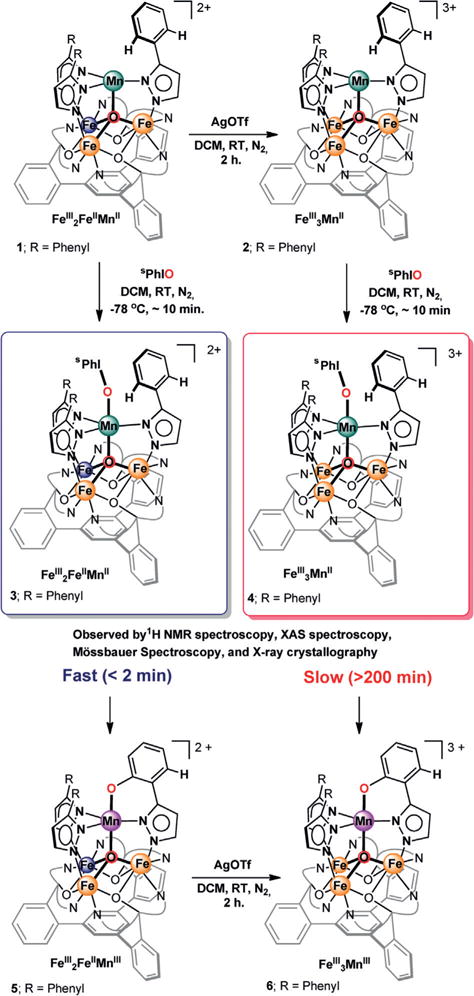

Access to different oxidation states (FeIII2FeIIMnII vs. FeIII3MnII) in complexes 1 and 2 allows for structure–reactivity studies. Given the function of the multinuclear oxygen evolving complex (OEC) in water oxidation and of diiron active sites in C–H oxygenation chemistry, O-atom transfer was studied by treatment of 1 and 2 with 2-(tert-butylsulfonyl)-iodosobenzene (sPhIO; 5.0 equiv). Indeed, en route towards intramolecular C–H bond oxygenation,[9] distinct intermediates (3, 4) were observed by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figures S3 and S4), where 4 exhibits diminished reactivity. No other intermediates were observed prior to the formation of [LFe3(PhPz)2(OArPz)OMn][OTf]x (Scheme 1. 5: x = 2; 6: x = 3).[10] Intrigued by the formation of 3 and 4, their structure and reactivity were further investigated by various analytical methods, where the relative stability of 4 enabled us to isolate crystals amenable for X-ray crystallography.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of triiron manganese clusters 1–6.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) studies on single crystals of 4 (Figure 2C), revealed the formation of a rare isolable iodosobenzene adduct [LFe3(PhPz)3OMn(sPhIO)][OTf]3. Comparing the O2−I1 (1.848(6) Å) and I1−C101 (2.128(7) Å) bond distances in 4 (Figure 2C), to those observed for free sPhIO (1.864(10) and 2.105(15) Å)[11] reveals no significant sPhIO activation (Table S1). This lack of activation is further corroborated by comparing the Mn1−O1 bond distances in complex 2 (2.166(3) Å) to those in 4 (2.100(6) Å). The long distances indicate that even upon binding of sPhIO, the manganese metal center remains MnII.[12] Subsequent XAS studies confirm such an assignment (see below).

The isolation of an iodosobenzene adduct bound to a low-valent MnII metal center is unique. To date, only two other examples are known where iodosobenzene is bound to a biologically relevant metal (Mn or Fe),[7b,c] none of them being on a multimetallic scaffold. Furthermore, in both complexes, the iodosobenzene is bound to higher oxidation state metal centers (FeIII and MnIV), which are less prone to further oxidation and feature larger degrees of PhIO activation. These differences suggest a multimetallic effect where the distal metal centers affect the reactivity of the MnII that ligates iodosobenzene.

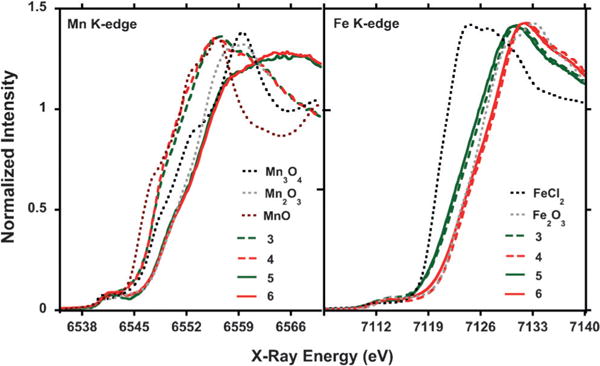

To gain further insight into the reactivity and oxidation state assignment of 3 and 4, their properties were investigated by X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). XAS is an element-specific technique that provides information about the oxidation state and local coordination environment of metal ions.[13] The Mn K-edge X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectra for complexes 3 and 4 are nearly identical, with rising edge energies (at half-height of the absorption edge) of 6547.8 eV (3) and 6547.7 eV (4) respectively (Figure 3; dashed green and red traces). These values are close to that recorded for MnO (6546.4 eV; Figure 3; dotted brown trace), and slightly lower than that recorded for mixed-valent Mn3O4 (6548.9 eV; Figure 3; dotted black trace). For comparison, the XANES spectra for 5 and 6 are clearly at a higher energy, where the rising edge energies obtained for 5 (6550.7 eV) and 6 (6550.9 eV) are close to that of Mn2IIIO3(6550.7 eV), suggesting the presence of higher oxidation state metal centers (Figure 3; solid green and red traces). The short Mn1−O1 (5: 1.894(7) Å; 6: 1.943(4) Å) and Mn1−O2 (5:1.854(7) Å; 6: 1.819(9) Å) bond distances support such an assignment (Figure 2B, Figure S24, Table S1).[14] The Mn XANES data thus indicate that prior to C–H bond oxygenation a lower oxidation state (MnII) metal center is present in 3 and 4, which oxidizes (to MnIII) along the reaction pathway. Moreover, the comparable shapes of the XAS spectra for 3 and 4 suggest a similar coordination geometry around the Mn metal center.[13] Based on these data, we propose that 3 is also an iodosobenzene adduct. The agreement between the Mn K-edge extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) derived bond distances in 3 (Mn−Oavg: 2.03 ± 0.02 Å; Mn−Navg: 2.18±0.03 Å) with those obtained by XRD in 4 (Mn−Oavg: 2.07±0.03 Å; Mn−Navg: 2.17±0.01 Å), supports such a proposal (Tables S4 and S5).[15]

Figure 3.

Normalized Mn and Fe K-edge XANES spectra (10 K) of compounds 3–6, compared to MnO, Mn2O3, Mn3O4 or to FeCl2, and Fe2O3.

The Fe K-edge XAS is very useful for establishing the iron oxidation states in 3, for which no Mössbauer or XRD data is available. The Fe K-edge XANES of 3 (Figure 3, dashed green trace) is in between that of Fe2O3 (FeIII; dotted gray trace) and FeCl2 (FeII; dotted black trace). The closer proximity of the rising edge energy in 3 (7122.2 eV) to that of Fe2O3 (7123.3 eV), indicates that the triiron core is of mixed valence and mainly FeIII in character. Moreover, the rising edge energy in 3 is nearly identical to that of 5 (7121.9 eV), for which a [FeIIFeIII2] oxidation state was established by Mössbauer spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography (Figures S19 and S23). The XAS data therefore indicates an overall [LFeIII2FeII(PhPz)3OMnII(sPhIO)][OTf]2 assignment for complex 3.

Analogous to 3, the Fe XANES spectrum of 4 is nearly identical to that of 6, suggesting the same oxidation state of the triiron core (Figure 3; dashed and solid red traces). The rising edge energies of 7123.8 eV (4) and 7123.5 eV (6) are very similar to that of Fe2O3 (7123.4 eV) suggesting an [FeIII3] assignment for the triiron core. The short Fecore−O1 distances of 1.994(7) Å (Fe1−O1), 1.989(7) Å (Fe2−O1), and 1.967(6) Å (Fe3−O1), are in line with such an assignment (Table S1).[16] The overall oxidation state in 4 is thus assigned as [LFeIII3(PhPz)3OMnII(sPhIO)][OTf]3 based on X-ray crystallography and XAS spectroscopy.

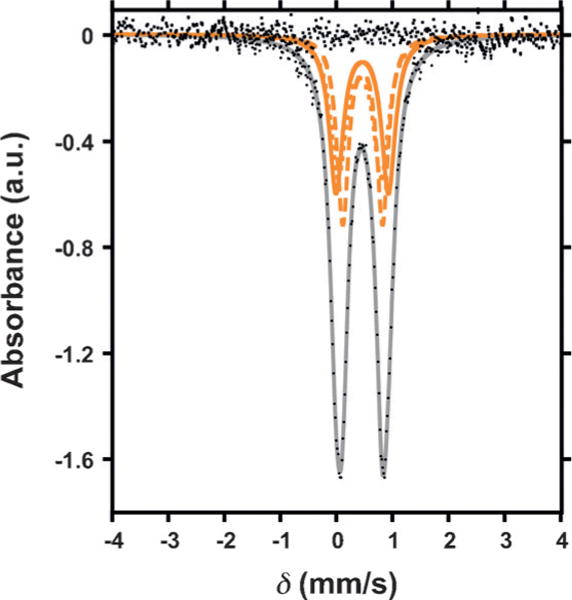

The presence of an [FeIII3] triiron core in 4 was further supported by Mössbauer spectroscopy (Figure 4). The Mössbauer spectrum was modeled as three nearly identical quadrupole doublets in a 1:1:1 ratio with isomer shifts of δ = 0.42 mms−1 (|ΔEQ|= 0.76 mms−1), δ = 0.46 mms−1 (|ΔEQ|= 0.92 mms−1), and δ = 0.47 mms−1 (|ΔEQ|= 0.71), consistent with the presence of three high spin ferric ions. The fitted parameters are similar to previously reported triiron oxo/hydroxo clusters.[16] Comparing the Mössbauer parameters of complexes 1, 2, and 4–6 (Figures S17–S19; Table S8), to our previously reported complexes [Fe3(PhPz)3OFe][OTf]x and [Fe3(PhPz)2(OArPz)OFe][OTf]x (x = 2–3) reveals a notable difference: the quadrupole doublet at δ ≈ 0.86 mms−1 (|ΔEQ| ≈ 1.57 mms−1), associated with the apical iron metal center, is absent in our Mössbauer spectra.[8,9] The absence is significant and implies that no metal scrambling occurs within our [LFe3(PhPz)3OMn][OTf]x (x = 2–3) clusters, confirming that reactivity originates from the Mn metal center.

Figure 4.

Zero-field 57Fe Mössbauer spectrum (80 K) of [LFe3(PhPz)3OMn(sPhIO)][OTf]3 (4).

Overall, prior to C–H bond oxygenation, XRD, XAS, and Mössbauer spectroscopy provide conclusive evidence for assigning 3 and 4 as iodosobenzene adducts [LFe3(PhPz)3OMn(sPhIO)][OTf]x (3: x = 2; 4: x = 3) in which a low-valent MnII metal center engages in the interaction with iodosobenzene. Accessing these intermediates offers a unique opportunity to study the effect of remote redox changes (FeIII2FeIIMnII vs. FeIII3MnII) on oxygen atom transfer. Indeed, pronounced redox state effects in 3 and 4 were observed. Warming a solution of 3 from −78°C to RT resulted—within two minutes—in the quantitative conversion to the C–H bond oxygenated product 5 (Scheme 1; Figure S9). In contrast, compound 4 persists for at least three hours (> 200 min) at RT; during which a gradual conversion to complex 6 occurs (Scheme 1; Figure S10). A difference of at least two orders of magnitude is observed for oxygen atom transfer in complexes 3 and 4.

The difference in reactivity between 3 and 4 is notable given that the XAS and XRD data (vide supra) suggest a similar degree of sPhIO activation. Assuming that sPhIO binds to the cluster as a neutral ligand, we propose that the redox properties of 3 and 4 should be comparable to their parent complexes 1 and 2.[8] Based on this assumption, we suggest that the reactivity differences between 3 and 4 are due to the higher oxidative stability of 4. The cyclic voltammogram of 1 is shown in Figure S11 and indeed reveals that the oxidation potential of 2 (FeIII3MnII) is at least 500 mV more positive than that of 1 (FeIII2FeIIMnII).[17] The increased oxidative stability of 2 results in a slower oxygen atom transfer reaction; prolonging the lifetime of 4, and hence, resulting in a more sluggish overall C–H oxygenation reaction.[18] Other effects such as spin-state changes, intramolecular electron transfer, or differences in the interaction with ancillary ligands cannot be ruled out. Nonetheless, these studies demonstrate a significant effect on reactivity where redox state changes at remote metal centers influence bond cleavage and formation at a distant Mn metal center. The observed differences suggest a path for the mechanism of C–H bond oxygenation. One can envision that the direct electrophilic attack or hydrogen atom abstraction from 3 or 4 would favor the metal complex with the highest oxidation potential.[19] However, here the opposite trend is observed, and is more consistent with the formation of a putative terminal MnIV-oxo, which if rate-limiting, is expected to be slower for the more oxidized metal cluster 4 compared to 3.

In summary, rare examples of iodosobenzene adducts [LFe3(PhPz)3OMn(sPhIO)][OTf]x. (3: x = 2; 4: x = 3) were characterized by a variety of spectroscopic methods. The first example of structurally characterized iodosobenzene adduct to a low oxidation state (MnII) metal center was reported. The oxidation states of a remote triiron core (FeIII2FeIIMnII vs. FeIII3MnII) was found to affect significantly oxygen atom transfer at a single manganese (MnII) metal center, and the overall C–H oxygenation chemistry in this system. These investigations provide a demonstration of the significant reactivity differences engendered by changes in the redox states of clusters, even at positions distant from where bond activations occur.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIH (R01-GM102687B). T.A. is grateful for Dreyfus and Cottrell fellowships. K.M.C is grateful for a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship. We thank Lawrence M. Henling for assistance with X-ray crystallography. Part of this research (XAS data collection) was carried out on beamline 7-3 at the SSRL, operated by Stanford University for the US DOE Office of Science, and supported by the DOE and NIH. XAS studies were performed with support of the Office of Science, OBES, Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences (CSGB) of the DOE under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231 (J.Y.).

Footnotes

Supporting information and the ORCID identification number(s) for the author(s) of this article can be found under: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201701319.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Dr. Graham de Ruiter, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering California Institute of Technology; MC 127-72 Pasadena, CA 91125 (USA).

Kurtis M. Carsch, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering California Institute of Technology; MC 127-72 Pasadena, CA 91125 (USA).

Dr. Sheraz Gul, Molecular Biophysics & Integrated Bioimaging Division Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Berkeley, CA 94720 (USA)

Dr. Ruchira Chatterjee, Molecular Biophysics & Integrated Bioimaging Division Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Berkeley, CA 94720 (USA)

Niklas B. Thompson, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering California Institute of Technology; MC 127-72 Pasadena, CA 91125 (USA)

Dr. Michael K. Takase, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering California Institute of Technology; MC 127-72 Pasadena, CA 91125 (USA)

Dr. Junko Yano, Molecular Biophysics & Integrated Bioimaging Division Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Berkeley, CA 94720 (USA)

Prof. Theodor Agapie, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering California Institute of Technology; MC 127-72 Pasadena, CA 91125 (USA)

References

- 1.a) Rittle J, Green MT. Science. 2010;330:933–937. doi: 10.1126/science.1193478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Price JC, Barr EW, Tirupati B, Bollinger JM, Krebs C. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7497–7508. doi: 10.1021/bi030011f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) McDonald AR, Que L., Jr Coord Chem Rev. 2013;257:414–428. [Google Scholar]; d) Krebs C, Galonić Fujimori D, Walsh CT, Bollinger JM. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:484–492. doi: 10.1021/ar700066p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que L. Chem Rev. 2004;104:939–986. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Yano J, Yachandra V. Chem Rev. 2014;114:4175–4205. doi: 10.1021/cr4004874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Park YJ, Matson EM, Nilges MJ, Fout AR. Chem Commun. 2015;51:5310–5313. doi: 10.1039/c4cc08603a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sahu S, Widger LR, Quesne MG, de Visser SP, Matsumura H, Moënne-Loccoz P, Siegler MA, Goldberg DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:10590–10593. doi: 10.1021/ja402688t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Taguchi T, Gupta R, Lassalle-Kaiser B, Boyce DW, Yachandra VK, Tolman WB, Yano J, Hendrich MP, Borovik AS. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:1996–1999. doi: 10.1021/ja210957u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Parsell TH, Yang MY, Borovik AS. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2762–2763. doi: 10.1021/ja8100825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) McGown AJ, Kerber WD, Fujii H, Goldberg DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:8040–8048. doi: 10.1021/ja809183z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Lansky DE, Goldberg DP. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:5119–5125. doi: 10.1021/ic060491+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Rohde J-U, In J-H, Lim MH, Brennessel WW, Bukowski MR, Stubna A, Münck E, Nam W, Que L. Science. 2003;299:1037–1039. doi: 10.1126/science.299.5609.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) MacBeth CE, Golombek AP, Young VG, Yang C, Kuczera K, Hendrich MP, Borovik AS. Science. 2000;289:938–941. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Gross Z, Golubkov G, Simkhovich L. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:4045–4047. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001117)39:22<4045::aid-anie4045>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2000;112:4211–4213. [Google Scholar]; j) Charnock JM, Garner CD, Trautwein AX, Bill E, Winkler H, Ayougou K, Mandon D, Weiss R. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1995;34:343–346. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 1995;107:370–373. [Google Scholar]; k) Groves JT, Stern MK. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:8628–8638. [Google Scholar]; l) Groves JT, Haushalter RC, Nakamura M, Nemo TE, Evans BJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:2884–2886. [Google Scholar]; m) Cook SA, Borovik AS. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:2407–2414. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n) Puri M, Que L. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:2443–2452. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; o) Nam W. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:2415–2423. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; p) Hohenberger J, Ray K, Meyer K. Nat Commun. 2012;3:720. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; q) Borovik AS. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:1870–1874. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00165a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Swart M, Costas M. Spin States in Biochemistry and Inorganic Chemistry. Wiley; Weinheim: 2015. [Google Scholar]; b) Usharani D, Janardanan D, Li C, Shaik S. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46:471–482. doi: 10.1021/ar300204y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Latifi R, Tahsini L, Karamzadeh B, Safari N, Nam W, de Visser SP. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;507:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Hirao H, Kumar D, Que L, Shaik S. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8590–8606. doi: 10.1021/ja061609o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Yang T, Quesne MG, Neu HM, Cantffl Reinhard FG, Goldberg DP, de Visser SP. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:12375–12386. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b05027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Boaz NC, Bell SR, Groves JT. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:2875–2885. doi: 10.1021/ja508759t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Usharani D, Lacy DC, Borovik AS, Shaik S. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:17090–17104. doi: 10.1021/ja408073m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Prokop KA, Neu HM, de Visser SP, Goldberg DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:15874–15877. doi: 10.1021/ja2066237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Arunkumar C, Lee YM, Lee JY, Fukuzumi S, Nam W. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:11482–11489. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsui EY, Kanady JS, Agapie T. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:13833–13848. doi: 10.1021/ic402236f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xue G, De Hont R, Münck E, Que L. Nat Chem. 2010;2:400–405. doi: 10.1038/nchem.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.A comprehensive CSD search (Feb 2017), revealed only three structures with a M⋯O⋯I⋯C motif:; a) Turlington CR, Morris J, White PS, Brennessel WW, Jones WD, Brookhart M, Templeton JL. Organometallics. 2014;33:4442–4448. [Google Scholar]; b) Wang C, Kurahashi T, Fujii H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:7809–7811. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2012;124:7929–7931. [Google Scholar]; c) Lennartson A, McKenzie CJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:6767–6770. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2012;124:6871–6874. [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Ruiter G, Thompson NB, Lionetti D, Agapie T. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:14094–14106. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b07397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Ruiter G, Thompson NB, Takase MK, Agapie T. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:1486–1489. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b12214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The formation of [LFe3(PhPz)2(OArPz)OMn][OTf]x (x = 2 or 3) proceeds with the formal loss of a H-atom. Similar reactivity has been observed in isostructural Fe4 complexes. See:; de Ruiter G, Thompson NB, Takase MK, Agapie T. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:1486–1489. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b12214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macikenas D, Skrzypczak-Jankun E, Protasiewicz JD. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:2007–2010. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000602)39:11<2007::aid-anie2007>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2000;112:2063–2066. [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Cotton FA, Daniels LM, Jordan GT, IV, Murillo CA, Pascual I. Inorg Chim Acta. 2000;297:6–10. [Google Scholar]; b) McKee V, Tandon SS. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1988:1334–1336. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yano J, Yachandra VK. Photosynth Res. 2009;102:241. doi: 10.1007/s11120-009-9473-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Nesterova OV, Chygorin EN, Kokozay VN, Omelchenko IV, Shishkin OV, Boca R, Pombeiro AJL. Dalton Trans. 2015;44:14918–14924. doi: 10.1039/c5dt02076j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Milios CJ, Piligkos S, Bell AR, Laye RH, Teat SJ, Vicente R, McInnes E, Escuer A, Perlepes SP, Winpenny REP. Inorg Chem Commun. 2006;9:638–641. [Google Scholar]

- 15.For a detailed discussion and analysis of the fitting parameters: see the Supporting Information.

- 16.Herbert DE, Lionetti D, Rittle J, Agapie T. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:19075–19078. doi: 10.1021/ja4104974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The oxidation of 2 is actually not observed in CH2Cl2 within the potential window of 0–1.0 V (vs. Fc/Fc+).

- 18.Unlike the study reported by Que and co-workers (Ref. [6]), this study does not address the reactivity differences of high-valent terminal MnIV-oxo species. The observed differences in this study are due to different rates of MnIV-oxo formation, generated by oxygen atom transfer from sPhIO to 1 or 2, which is the rate limiting step. High-valent MnIV-oxo formation was not observed, most likely due to a fast C–H oxygenation step.

- 19.a) Neu HM, Baglia RA, Goldberg DP. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:2754–2764. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hong S, Wang B, Seo MS, Lee Y-M, Kim MJ, Kim HR, Ogura T, Garcia-Serres R, Clémancey M, Latour J-M, Nam W. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:6388–6392. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2014;126:6506–6510. [Google Scholar]; c) Collman JP, Chien AS, Eberspacher TA, Brauman JI. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:11098–11100. [Google Scholar]; d) Jin N, Groves JT. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:2923–2924. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.