Abstract

Background

Post-breakfast/post-challenge plasma glucose (PG) concentrations were studied less in young normal weight Japanese women. We addressed these issues.

Methods

Two separate groups of female collegiate athletes and female untrained students underwent either a standardized meal test or a standard 75-g oral glucose tolerance test, but not both. Frequency of women whose post-breakfast/post-load PG fell to 70 mg/dL or lower (termed as low glycemia) was compared between athletes and non-athletes, who also underwent measurements of serum adipokines, markers of insulin resistance and inflammation and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Insulin secretion, insulin sensitivity/resistance and serum adipokines were compared between women with and without post-breakfast low glycemia. The same comparison was done between women whose post-breakfast PG returned to levels below the fasting PG and women whose post-breakfast PG never fell below the fasting PG.

Results

There was no difference between athletes and non-athletes in frequency of post-breakfast low glycemia (47% (8/17) and 44% (8/18)) and post-challenge low glycemia (24% (12/50) and 23% (27/118)). As compared to seven women whose post-breakfast PG never fell below the fasting PG, 28 women whose post-breakfast PG returned to levels below the fasting PG had higher meal-induced insulin responses (283 ± 366 vs. 89 ± 36 µU/mg, P = 0.014). However, two groups did not differ in body composition, markers of insulin resistance and serum adiponectin. No significant difference was also observed in any of these variables between women with and without post-breakfast low glycemia.

Conclusion

Post-prandial PG ≤ 70 mg/dL is not uncommon in young normal weight Japanese women and may not be a pathological condition. The underlying mechanisms for this finding need further exploration.

Keywords: Post-breakfast glycemia, Post-challenge glycemia, Meal test, Oral glucose tolerance test, Young women

Introduction

The proportions of people with type 2 diabetes and obesity have increased throughout Asia [1]. People in Asia tend to develop diabetes with a lesser degree of obesity at younger ages [1]. The American Diabetes Association Workgroup on Hypoglycemia [2] suggested that patients at risk for hypoglycemia (i.e., those treated with a sulfonylurea, glinide, or insulin) should be alert to the possibility of developing hypoglycemia at a self-monitored blood glucose - or continuous glucose monitoring subcutaneous glucose - concentration of ≤ 70 mg/dL. We had an opportunity to see changes in plasma glucose (PG) concentrations in response to a standardized breakfast as well as during an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) in young women [3, 4]. During meal tests and OGTT, nobody had any signs or symptoms at all. We were very surprised to see that a substantial number of women experienced post-challenge/post-breakfast PG ≤ 70 mg/dL.

Participants and Methods

We studied 67 female collegiate athletes and 136 untrained female students aged 18 - 24 years, whose details have been reported elsewhere [3-6]. They were all Japanese and those with clinically diagnosed acute or chronic inflammatory diseases, endocrine, cardiovascular, hepatic, renal diseases, hormonal contraception, and unusual dietary habits were excluded. Nobody received any medications. The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the University (No. 07-28) to be in accordance with the Helsinki declaration. All subjects gave written consent after the experimental procedure had been explained.

After a 12-h overnight fast in the morning, a standard 75-g OGTT was performed in 50 athletes and 118 non-athletes, as previously reported in details [4]. Another set of 17 athletes and 18 non-athletes underwent a standardized meal test [4]. PG and serum insulin were measured at 0 (baseline), 30, 60, and 120 min. The test meal was developed by the Japanese Diabetes Society to assess both post-prandial hyperglycemia and hyperlipemia [7]. This meal was composed as a breakfast meal (total energy 450 kcal) consisting of biscuit (83 kcal), cream of chicken soup (272 kcal) and custard pudding (95 kcal). The meal provided 33.3% of calories from fat (16.7 g), 51.4% from carbohydrates (57.8 g), and 15.3% from protein (17.2 g). The test meal contained more fat than a typical Japanese breakfast (20-25%).

PG was determined by the hexokinase/glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase method (intera-ssay coefficient of variation (CV) < 2%) and serum insulin by an ELISA method as previously reported in details [5, 6]. Insulin resistance (IR) was evaluated by homeostasis model assessment of IR (HOMA-IR) [8] and adipose IR [9]. Meal-induced insulin response (MIR) was calculated as the ratio of changes in insulin to those in glucose level during the first 30 min of a meal test (30-min insulin level - fasting insulin)/(30-min PG - fasting PG), where insulin in µU/mL and glucose in mg/mL were not in mg/dL. MIR is analogous to insulinogenic index, a marker of early-phase insulin secretion, and expressed in µU/mg. Women whose post-breakfast/post-load PG fell to 70 mg/dL or lower at any time point during a meal test/OGTT were defined as having low glycemia.

Adiponectin was assayed by a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokushima, Japan). Intra- and inter-assay CVs were 3.3% and 7.5%, respectively. Leptin was assessed by an RIA kit from LINCO research (St. Charles, MO, inter-assay CV = 4.9%). High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) was measured by an immunoturbidometric assay with the use of reagents and calibrators from Dade Behring Marburg GmbH (Marburg, Germany; inter-assay CV < 5.0%). Interleukine-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) were measured by enzyme immunoassay and immunoassays (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, inter-assay CV = 6.0%), respectively. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) was measured by an ELISA method (Mitsubishi Chemicals, inter-assay CV = 8.1%).

Data were presented as mean ± SD. Due to deviation from normal distribution, hsCRP was logarithmically transformed for analysis. Differences between two groups in means and percentages were compared by t-test and Chi-square test, respectively. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All calculations were performed with SPSS system 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

The test meal breakfast was well tolerated and nobody had any symptoms and signs. The lowest post-breakfast PG concentrations were 51 and 59 mg/dL at 60 and 120 min, respectively, and median PG fell to 72 mg/dL at 120 min (Table 1). Post-breakfast low glycemia at 60 and 120 min was found in eight (23%) and 14 (40%) of participants, respectively (Table 1). Altogether, 16 women (46%) experienced post-breakfast low glycemia at least once during the observation period. Frequency of post-breakfast low glycemia did not differ between non-athletes (44% (8/18) and athletes 47% (8/17), respectively).

Table 1. Plasma Glucose, Serum Insulin in Response to a Standardized Breakfast (Test Meal A) and Percentages of Women With Post-Breakfast Low Glycemia (Plasma Glucose < 70 mg/dL) in 35 Young Japanese Women.

| Glucose at | Minimum (mg/dL) | Median (mg/dL) | Maximum (mg/dL) | Low glycemia (n, %) | Insulin, mean ± SD (µU/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 min | 78 | 83 | 95 | 0 | 3.7 ± 2.0 |

| 30 min | 72 | 108 | 135 | 0 | 33.1 ± 17.8 |

| 60 min | 51 | 85 | 128 | 8 (22.8) | 27.6 ± 16.6 |

| 120 min | 59 | 72 | 98 | 14 (40.0) | 12.5 ± 8.0 |

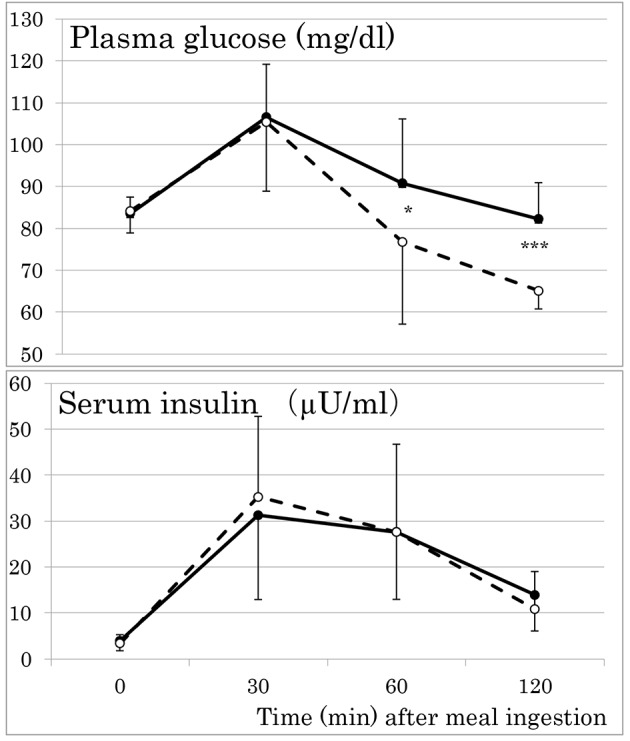

Mean PG fell to 65 mg/dL at 120 min in women with post-breakfast low glycemia (Fig. 1), whereas there was no difference in fasting and post-breakfast insulinemia at any time point during meal tests between women with and without low glycemia. No significant group differences were also observed in anthropometric variables including trunk/leg fat ratio, a marker of abdominal fat accumulation [10] (Table 2), MIR, HOMA-IR, adipose IR, serum adipokines including adiponectin and inflammatory and hemostasis markers (Table 3). Serum lipids, lipoproteins, apolipoproteins, liver enzymes and blood pressure did no differ between women with and without low glycemia as well.

Figure 1.

Responses of plasma glucose and serum insulin to a standardized test meal in young women with (broken lines) and without (solid lines) post-breakfast low glycemia (plasma glucose ≤ 70 mg/dL). Mean ± SD. *P < 0.05. ***P < 0.001.

Table 2. Anthropometric Features of Young Women With and Without Post-Breakfast Low Glycemia (Plasma Glucose ≤ 70 mg/dL).

| Post-breakfast low glycemia, mean ± SD |

P value |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Absent (n = 19) | Present (n = 16) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.8 ± 2.5 | 21.9 ± 2.4 | 0.930 |

| FMI (kg/m2) | 10.1 ± 3.4 | 10.0 ± 2.3 | 0.896 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 74.1 ± 6.3 | 73.4 ± 6.4 | 0.739 |

| Arms fat mass (kg) | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 0.550 |

| Legs fat mass (kg) | 5.9 ± 1.7 | 6.3 ± 2.5 | 0.592 |

| Trunk fat mass (kg) | 7.5 ± 3.1 | 7.1 ± 2.3 | 0.692 |

| Total fat mass (kg) | 15.1 ± 5.4 | 15.3 ± 5.2 | 0.937 |

| Arm FMI (kg/m2) | 0.45 ± 0.24 | 0.49 ± 0.25 | 0.630 |

| Legs FMI (kg/m2) | 2.25 ± 0.70 | 2.36 ± 0.88 | 0.666 |

| Trunk FMI (kg/m2) | 2.88 ± 1.24 | 2.70 ± 0.81 | 0.628 |

| Arms lean mass (kg) | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 0.307 |

| Legs lean mass (kg) | 13.5 ± 2.4 | 13.6 ± 2.1 | 0.888 |

| Trunk lean mass (kg) | 18.7 ± 2.6 | 18.5 ± 2.6 | 0.805 |

| Total lean mass (kg) | 39.1 ± 5.7 | 39.2 ± 5.4 | 0.949 |

| Arms percentage fat (%) | 22.3 ± 9.5 | 22.8 ± 8.0 | 0.877 |

| Legs percentage fat (%) | 28.9 ± 7.1 | 29.4 ± 6.4 | 0.830 |

| Trunk percentage fat (%) | 27.2 ± 8.6 | 26.6 ± 6.0 | 0.818 |

| Total percentage fat (%) | 26.3 ± 7.5 | 26.3 ± 5.7 | 0.993 |

| Trunk/leg fat mass | 1.25 ± 0.25 | 1.18 ± 0.26 | 0.435 |

FMI: fat mass index.

Table 3. Biochemical Features of Young Women With and Without Post-Breakfast Low Glycemia (Plasma Glucose ≤ 70 mg/dL).

| Post-breakfast low glycemia, mean ± SD |

P value |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Absent (n = 19) | Present (n = 16) | ||

| HbA1c (%) | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 0.742 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.82 ± 0.47 | 0.70 ± 0.37 | 0.428 |

| MIR (µU/mg) | 225 ± 353 | 265 ± 318 | 0.738 |

| Adipose IR | 1.89 ± 0.82 | 1.48 ± 1.13 | 0.228 |

| PAI-1 (ng/mL) | 24.0 ± 9.3 | 36.0 ± 27.1 | 0.079 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.228 |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 7.3 ± 5.2 | 6.6 ± 3.1 | 0.631 |

| Adiponectin (µg/mL) | 10.4 ± 3.2 | 12.1 ± 5.6 | 0.268 |

| Leptin/adiponectin ratio | 0.77 ± 0.59 | 0.66 ± 0.50 | 0.535 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 0.68 ± 0.33 | 0.64 ± 0.29 | 0.680 |

| AST (U/L) | 18.3 ± 4.0 | 16.8 ± 6.9 | 0.428 |

| ALT (U/L) | 13.3 ± 4.3 | 12.1 ± 3.9 | 0.378 |

| GGT (U/L) | 12.4 ± 2.8 | 12.5 ± 2.7 | 0.933 |

| Apolipoprotein A1 (mg/dL) | 161 ± 14 | 157 ± 15 | 0.470 |

| Apolipoprotein B (mg/dL) | 67 ± 15 | 66 ± 13 | 0.948 |

| Total-C (mg/dL) | 180 ± 23 | 177 ± 23 | 0.726 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 75 ± 12 | 72 ± 11 | 0.416 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 93 ± 20 | 94 ± 19 | 0.830 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 57 ± 21 | 52 ± 15 | 0.444 |

| RLP-C (mg/dL) | 2.9 ± 1.2 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 0.505 |

| FFA (mEq/L) | 0.51 ± 0.14 | 0.42 ± 0.17 | 0.108 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 114 ± 7 | 111 ± 8 | 0.321 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 69 ± 6 | 66 ± 6 | 0.083 |

HOMA: homeostasis model assessment; IR: insulin resistance; MIR: meal-induced insulin response; PAI-1: plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α; hsCRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL-6: interleukine-6; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; GGT: γ-glutamyltransferase; C: cholesterol; TG: triglyceride; RLP: remnant-like lipoprotein; FFA: free fatty acid; BP: blood pressure.

Responses to test meal of triglyceride, remnant-like lipoprotein-cholesterol and free fatty acid in young women with and without post-breakfast low glycemia were summarized in Table 4. Again, no group difference was observed. After meal ingestion, there were modest increases in triglyceride and no change in remnant-like lipoprotein-cholesterol. Free fatty acid fell in response to meal ingestion, suggesting good insulin sensitivity of adipose tissue, as previously reported [4].

Table 4. Responses to Test Meal of Triglyceride, Remnant-Like Lipoprotein-Cholesterol and Free Fatty Acid in Young Women With and Without Post-Breakfast Low Glycemia (Plasma Glucose ≤ 70 mg/dL).

| Post-breakfast low glycemia, mean ± SD |

P value |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Absent (n = 19) | Present (n = 16) | ||

| TG 0 min (mg/dL) | 57 ± 21 | 52 ± 15 | 0.444 |

| TG 30 min (mg/dL) | 62 ± 23 | 60 ± 23 | 0.739 |

| TG 60 min (mg/dL) | 73 ± 28 | 72 ± 24 | 0.902 |

| TG 120 min (mg/dL) | 77 ± 29 | 82 ± 31 | 0.673 |

| RLP-C 0 min (mg/dL) | 2.9 ± 1.2 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 0.505 |

| RLP-C 30 min (mg/dL) | 3.0 ± 1.2 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 0.468 |

| RLP-C 60 min (mg/dL) | 3.3 ± 1.4 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 0.451 |

| RLP-C 120 min (mg/dL) | 3.1 ± 1.3 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 0.806 |

| FFA 0 min (mEq/L) | 0.51 ± 0.14 | 0.42 ± 0.17 | 0.108 |

| FFA 30 min (mEq/L) | 0.38 ± 0.11 | 0.32 ± 0.11 | 0.129 |

| FFA 60 min (mEq/L) | 0.24 ± 0.06 | 0.23 ± 0.08 | 0.523 |

| FFA 120 min (mEq/L) | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.07 | 0.168 |

TG: triglyceride; RLP-C: remnant-like lipoprotein-cholesterol; FFA: free fatty acid.

Post-challenge low glycemia was found in 23% (27/118) of non-athletes as well as in 24% of athletes (12/50). When athletes and non-athletes were combined, frequency of post-breakfast low glycemia was twice as high as frequency of post-challenge low glycemia (46% (16/35) vs. 23% (39/168)).

It has been reported that subjects whose post-load PG returned to levels below the fasting PG had a lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared with subjects whose post-load glucose never fell below the fasting PG [11]. Therefore, MIR, insulin sensitivity/resistance and serum adiponectin were compared between 28 women whose post-breakfast PG returned to levels below the fasting PG and seven women whose post-breakfast PG never fell below the fasting PG concentration (Table 5). The former had higher MIR and lower 120-min PG than the latter, whereas two groups did not differ in the percentage of athletes, body composition, markers of IR and serum adiponectin.

Table 5. Comparison Between 28 Young Japanese Women Whose Post-Breakfast Plasma Glucose (PG) Returned to Levels Below the Fasting PG (A) and 7 Women Whose Post-Breakfast PG Never Fell Below the Fasting PG Concentration (B).

| B, mean ± SD | A, mean ± SD | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Athletes (n, %) | 4 (57.1) | 13 (46.4) | 0.691 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.3 ± 1.5 | 22.0 ± 2.6 | 0.489 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 71.4 ± 4.2 | 74.4 ± 6.6 | 0.268 |

| Fat mass index (kg/m2) | 5.42 ± 1.32 | 5.87 ± 2.16 | 0.606 |

| Percentage body fat (%) | 25.8 ± 6.0 | 26.5 ± 6.9 | 0.827 |

| Trunk/leg fat mass | 1.24 ± 0.16 | 1.21 ± 0.27 | 0.799 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) 0 min | 82 ± 4 | 84 ± 5 | 0.273 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) 30 min | 111 ± 9 | 105 ± 15 | 0.355 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) 60 min | 95 ± 16 | 82 ± 19 | 0.100 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) 120 min | 90 ± 5 | 70 ± 8 | 0.000 |

| Insulin (µU/mL) 0 min | 3.3 ± 1.2 | 3.8 ± 2.2 | 0.594 |

| Insulin (µU/mL) 30 min | 29.4 ± 15.8 | 34.0 ± 18.4 | 0.554 |

| Insulin (µU/mL) 60 min | 22.4 ± 14.4 | 28.9 ± 17.1 | 0.361 |

| Insulin (µU/mL) 120 min | 14.6 ± 8.5 | 12.0 ± 8.0 | 0.436 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 0.848 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.67 ± 0.23 | 0.79 ± 0.46 | 0.519 |

| MIR (µU/mg) | 89 ± 36 | 283 ± 366 | 0.014 |

| Adipose IR | 1.90 ± 0.76 | 1.66 ± 1.04 | 0.565 |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 6.5 ± 4.1 | 7.1 ± 4.5 | 0.737 |

| Adiponectin (µg/mL) | 10.5 ± 2.7 | 11.4 ± 4.8 | 0.631 |

HOMA: homeostasis model assessment; IR: insulin resistance; MIR: meal-induced insulin response.

Discussion

Iatrogenic hypoglycemia is harmful in patients with diabetes and is sometimes fatal. The alert value, a PG of ≤ 70 mg/dL, can be used as a cut-off value in the classification of hypoglycemia in diabetes [2]. However, this alert value is data driven and pragmatic, and a single threshold value for PG concentration that defines hypoglycemia in diabetes cannot be assigned [2]. The present study has demonstrated that 46% of young normal weight Japanese women experienced post-breakfast PG ≤ 70 mg/dL, which was not associated with any signs and symptoms. This has been confirmed by OGTT, which has revealed that 23% of young Japanese women had post-challenge low glycemia. These findings suggest that post-prandial PG ≤ 70 mg/dL is not uncommon in young normal weight Japanese women and that it may not be a pathological condition.

Adding protein and fat macronutrients to glucose in a mixed meal diminished glucose excursion as compared with the same amount of glucose challenge alone [12]. This occurred in association with increased β-cell function, reduced insulin clearance, delayed gastric emptying and augmented glucagon and GIP secretion [12]. These findings may be in line with our observation that post-prandial low glycemia was frequently observed more after meal ingestion (58 g carbohydrates) than after 75 g glucose ingestion in young women.

Although subjects with normal glucose tolerance (NGT) have a lower relative risk for progression to diabetes than subjects with either impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose, 30-40% of subjects who develop diabetes had NGT at baseline [13-16]. In the San Antonio Heart Study [11], subjects with NGT whose post-load PG concentration returned to levels below the fasting PG concentration had a lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared with subjects whose post-load glucose concentration never fell below the fasting PG concentration. These observations suggest that young women with post-breakfast or post-challenge low glycemia in the present study may have a lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes than women who did not have low glycemia.

Chronic low-grade inflammation links obesity in general, abdominal obesity in particular, to insulin resistance and β cell failure [17]. In the above mentioned San Antonio Heart Study [11], subjects with NGT whose post-load PG concentration returned to levels below the fasting PG concentration had lower BMI, waist circumference and serum triglycerides, and higher HDL cholesterol, greater insulin sensitivity, and a higher insulinogenic index, a marker of early-phase insulin secretion, compared with subjects whose post-load glucose concentration never fell below the fasting PG concentration. In the present study, women whose post-breakfast PG returned to levels below the fasting PG had higher MIR, which is analogous to insulinogenic index, than women whose post-breakfast PG never fell below the fasting PG concentration, although above mentioned features of abdominal obesity did not differ between the two groups as well as young women with and without post-breakfast low glycemia. As frequency of post-breakfast/post-challenge low glycemia did not differ between endurance-trained athletes and sedentary non-athletes in the present study, it is likely that higher early-phase insulin secretion rather than insulin sensitivity may be associated with post-breakfast low glycemia, although underlying mechanisms for the present findings need further exploration.

This study has several strengths, including a homogeneous study population with scarce confounding factors, and accurate and reliable measures of body composition by DXA. The main limitation of our study is small sample size. The cross-sectional design of the present study complicates the drawing of causal inferences, and a single measurement of biochemical variables may be susceptible to short-term variation, which would bias the results toward the null. We used several surrogates in the present study, which may be less accurate.

Conclusions

Post-prandial PG ≤ 70 mg/dL is not uncommon in young normal weight Japanese women and may not be a pathological condition.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants for their dedicated and conscientious collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

MT, AT KK, SM and MK collected and analyzed data. TK wrote the manuscript, and KF reviewed and edited it. TK supervised the study, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Abbreviations

- PG

plasma glucose

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- IR

insulin resistance

- HOMA

homeostasis model assessment

- MIR

meal-induced insulin response

- NGT

normal glucose tolerance

References

- 1.Yoon KH, Lee JH, Kim JW, Cho JH, Choi YH, Ko SH, Zimmet P. et al. Epidemic obesity and type 2 diabetes in Asia. Lancet. 2006;368(9548):1681–1688. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association Workgroup on Hypoglycemia. Defining and reporting hypoglycemia in diabetes: a report from the American Diabetes Association Workgroup on Hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(5):1245–1249. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terazawa-Watanabe M, Tsuboi A, Fukuo K, Kazumi T. Association of adiponectin with serum preheparin lipoprotein lipase mass in women independent of fat mass and distribution, insulin resistance, and inflammation. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2014;12(8):416–421. doi: 10.1089/met.2014.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitaoka K, Takeuchi M, Tsuboi A, Minato S, Kurata M, Tanaka S, Kazumi T. et al. Increased Adipose and Muscle Insulin Sensitivity Without Changes in Serum Adiponectin in Young Female Collegiate Athletes. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2017;15(5):246–251. doi: 10.1089/met.2017.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka S, Wu B, Honda M, Suzuki K, Yoshino G, Fukuo K, Kazumi T. Associations of lower-body fat mass with favorable profile of lipoproteins and adipokines in healthy, slim women in early adulthood. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2011;18(5):365–372. doi: 10.5551/jat.7229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka M, Yoshida T, Bin W, Fukuo K, Kazumi T. FTO, abdominal adiposity, fasting hyperglycemia associated with elevated HbA1c in Japanese middle-aged women. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2012;19(7):633–642. doi: 10.5551/jat.11940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshino G, Tominaga M, Hirano T, Shiba T, Kashiwagi A, Tanaka A. et al. The test meal A: a pilot model for the international standard of test meal for an assessment of both postprandial hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia. J Japan Diab Soc. 2006;49(5):361–371. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malin SK, Kashyap SR, Hammel J, Miyazaki Y, DeFronzo RA, Kirwan JP. Adjusting glucose-stimulated insulin secretion for adipose insulin resistance: an index of beta-cell function in obese adults. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(11):2940–2946. doi: 10.2337/dc13-3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim U, Turner SD, Franke AA, Cooney RV, Wilkens LR, Ernst T, Albright CL. et al. Predicting total, abdominal, visceral and hepatic adiposity with circulating biomarkers in Caucasian and Japanese American women. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdul-Ghani MA, Williams K, DeFronzo R, Stern M. Risk of progression to type 2 diabetes based on relationship between postload plasma glucose and fasting plasma glucose. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(7):1613–1618. doi: 10.2337/dc05-1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alsalim W, Tura A, Pacini G, Omar B, Bizzotto R, Mari A, Ahren B. Mixed meal ingestion diminishes glucose excursion in comparison with glucose ingestion via several adaptive mechanisms in people with and without type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(1):24–33. doi: 10.1111/dom.12570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Unwin N, Shaw J, Zimmet P, Alberti KG. Impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glycaemia: the current status on definition and intervention. Diabet Med. 2002;19(9):708–723. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, de Courten M, Dowse GK, Chitson P, Gareeboo H, Hemraj F. et al. Impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance. What best predicts future diabetes in Mauritius? Diabetes Care. 1999;22(3):399–402. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabir MM, Hanson RL, Dabelea D, Imperatore G, Roumain J, Bennett PH, Knowler WC. Plasma glucose and prediction of microvascular disease and mortality: evaluation of 1997 American Diabetes Association and 1999 World Health Organization criteria for diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(8):1113–1118. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.8.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Vegt F, Dekker JM, Stehouwer CD, Nijpels G, Bouter LM, Heine RJ. The 1997 American Diabetes Association criteria versus the 1985 World Health Organization criteria for the diagnosis of abnormal glucose tolerance: poor agreement in the Hoorn Study. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(10):1686–1690. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.10.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khodabandehloo H, Gorgani-Firuzjaee S, Panahi G, Meshkani R. Molecular and cellular mechanisms linking inflammation to insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction. Transl Res. 2016;167(1):228–256. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]