Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to determine whether arterial blood lactate concentration at the end of liver transplantation is associated with major postoperative complications, length of Intensive Care Unit (ICU) stay and mortality.

Methods

Arterial lactate concentration was recorded at the end of surgery in 48 patients (30 males and 18 females) who had underwent liver transplantation (LT) over a six month period between June 2013 and December 2013. Demographic data, laboratory results and postoperative outcome were recorded.

Results

The mean age in the study group was 51.14 years (16–62); all the patients had undergone deceased-donor liver transplantation. The etiology of liver disease was various: viral infections (HBV and HCV), alcoholic cirrhosis, hepatocarcinoma and other rare causes of cirrhosis (Wilson disease) were found. The mean duration of surgery was 407 minutes (240–580). Mean lactate was 2.77 mmol/L (0.8–7.9) and was increased above 1.5 mmol/L in 33 (68.75%) patients. ICU length of stay was longer in patients having lactate levels > 5 mmol/L (p = 0.05). Intraoperative blood loss was higher in patients with lactate > 3 mmol/L (p = 0.012). Major complications including acute kidney injury, need for emergency surgery during ICU stay or primary graft disfunction were observed only in patients with lactate levels > 1.5 mmol/L (18.2%). Sixty days mortality was 100% in the group with lactate > 5 mmol/L (4 patients) compared with 12.5% mortality in patients with lactate level < 5 mmol/L (p = 0.05).

Conclusions

Arterial lactate concentrations at the end of liver transplantation correlates with increased intraoperative blood loss, longer ICU stay, and increased mortality.

Keywords: liver transplantation, arterial lactate concentration, postoperative outcome

Rezumat

Obiectiv

Scopul acestui studiu a fost determinarea unei relaţii între nivelul arterial al lactatului şi evoluţia postoperatorie a pacienţilor transplantaţi hepatic: apariţia complicaţiilor, durata internării pe secţia de terapie intensivă şi mortalitatea.

Material şi metodă

Concentraţia arterială a lactatului a fost măsurată la sfârşitul intervenţiei chirurgicale la 48 de pacienţi (dintre care 30 bărbaţi şi 18 femei) supuşi transplantului cu ficat întreg de la donator aflat în moarte cerebrală, în perioada iunie 2013 – decembrie 2013. S-au înregistrat date demografice, de laborator precum şi evoluţia postoperatorie şi complicaţiile apărute.

Rezultate

Vârsta medie a fost de 51,14 ani (16–62). Etiologia afectării hepatice a variat: infecţiile virale (VHB şi VHC), ciroza alcoolică, hepatocarcinomul precum şi alte cauze rare (boala Wilson) au fost întâlnite. Durata medie a intervenţiei chirurgicale a fost de 407 minute (240–580). Nivelul mediu al lactatului a fost de 2,77 mmol/l (0,8–7,9) şi a crescut peste valoarea normală de 1,5 mmol/l la 33 (68,75%) dintre pacienţi. Durata internării pe secţia de terapie intensivă a fost prelungită la pacienţii cu nivelul lactatului > 5 mmol/l (p = 0,05). Sângerarea intraoperatorie a fost mai mare la pacienţii cu valoarea lactatului > 3 mmol/l (p = 0,012). Complicaţii majore incluzând insuficienţa renală acută, reintervenţia chirurgicală de urgenţă sau disfuncţia primară de grefă s-au observat la 18,2% din pacienţi cu lactat > 1,5 mmol/l. Mortalitatea la 60 de zile postoperator a fost de 100% la cei cu lactat > 5 mmol/l (4 pacienţi) comparativ cu 12,5% la pacienţii cu lactat < 5 mmol/l (p = 0,05).

Concluzii

Concentraţia lactatului la sfârşitul intervenţiei chirurgicale de transplant hepatic a fost asociată cu sângerarea intraoperatorie, creşterea duratei de staţionare în secţia de terapie intensivă şi creşterea mortalităţii.

Introduction

Ever since the first successful liver transplant was performed in 1967, this procedure has evolved to become a well-established treatment modality for patients with end stage liver disease (ESLD) [1]. However, the operation is not without risk-it carries a 5–10% incidence of 30 days mortality [2].

Current trends stress several pretransplant factors that can predict morbidity and mortality including Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-Na (MELD-Na) scores, malnutrition, technically complex surgery indexes or Child-Pugh classification [3,4]. During anaesthesia, an imbalance in lactate production versus lactate utilization due to tissue hypoperfusion or decreased liver function results in lactic acidosis. Temporary absence of the liver during liver transplantation (LT) results in lactic acidosis which usually resolves after the graft recovers [5]. Lactic acid is a by-product of the anaerobic metabolism that is subsequently metabolised in the liver during gluconeogenesis. Hyperlactatemia has been shown to be associated with increased mortality and morbidity in a critical care setting in patients following liver resection [6] or trauma [7].

There are several studies that stress the connection between arterial lactate and postoperative outcome in liver resections, but only a few address liver transplantation. This is one of the reasons we think our study brings new data to the current knowledge on this topic.

The aim of this study was to evaluate whether arterial blood lactate concentration at the end of liver transplantation is associated with major postoperative complications (defined as primary graft dysfunction, hemoperitoneum and acute kidney injury), length of Intensive Care Unit (ICU) stay and mortality.

Patients and method

After obtaining approval by the Ethical Committee of the Fundeni Clinical Institute, we retrospectively analyzed 48 patients who had undergone LT at the Fundeni Clinical Institute between June 2013 – December 2013. Inclusion criteria were available measurements of the arterial lactate concentration at the end of the hepatic transplantation and data regarding postoperative outcome – complications and 60 days mortality.

The patients were divided into four groups taking the lactate value into consideration: group I with normal lactate, group II with values ranging from 1.5 to 3 mmol/L, group III with lactate levels between 3 and 5 mmol/L and the last group, group IV, with lactate levels above 5 mmol/L.

Data collection

Preoperative data were collected from the patient’s medical files: age, gender, etiology of liver disease, assessment scores for the severity of liver disease (MELD and MELD-Na scores). Intraoperative data were: duration of surgery, blood loss and blood transfusion, duration of the anhepatic phase, arterial blood lactate at the end of the LT. Postoperative collected data were: length of PACU stay, incidence and severity of postoperative complications and at 60 days mortality.

Anaesthetic management

The patients in the study underwent LT under general anaesthesia. Induction was obtained using propofol 1.2 mg/kg, fentanyl 2–4 μg/kg and succinylcholine 1 mg/kg. Neuromuscular blockade was obtained with atracurium, a loading dose followed by boluses every 20–45 minutes. Maintenance of anaesthesia was achieved using inhaled sevoflurane and fentanyl. Intraoperative monitoring consisted of continuous electrocardiogram, invasive blood pressure (BP) measurement, peripheral oxygen saturation, end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2), diuresis and core temperature. Invasive BP, CVP, cardiac output and derived values (CI, SVRI, SVV, GEDI, GEF, ELWI) were monitored with pulse contour analysis using PICCO Plus®monitor.

Arterial lactate concentration

Abnormal arterial lactate concentration was defined as values above 1.5 mmol/L. The arterial lactate concentration was measured constantly (every 30 minutes) during the liver transplantation. Despite these measurements, only lactate levels determined at the end of the surgery were included in the study. All the measurements were made on two different types of machines: ABL800 Basic (Radiometer America Inc., 2012) and 800 RapidLab (Bayer Healthcare, 2010). Both machines offer reliable and exact information that do not vary with the changing of the device.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as a mean ± standard deviation of the mean, median [min, max] and percentage. Data distribution was examined in order to ensure the proper statistical examination; a linear continuous distribution was observed. Demographic and physiological characteristics for the four groups were compared using the t-test (Two-Sample Assuming Unequal Variances, one tail) for continuous data. In order to assess subgroup differences we used the Pearson correlation test. Statistical significance was considered at a p-value under 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Office Excel 2007.

Results

The mean age of the patients in the study group was 51.14 ± 8.73 years with a range distribution from 16 to 62 years. All the patients in this study (30 males and 18 females) had undergone deceased-donor liver transplantation. The mean MELD score was 16.2 ± 3.42 (14–30). Epidemiologic and transplant data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Epidemiologic and transplant data

| All patients (n = 48) | Group 1 (n = 15) | Group 2 (n = 14) | Group 3 (n = 15) | Group 4 (n = 4) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 51.14 ± 8.73 | 51.86 ± 5.47 | 46.57 ± 11.6 | 57.73 + 4.18 | 39.75 ± 17.25 | |

| Sex | Male | 30 (62.5%) | 10 (66.6%) | 9 (64.2%) | 9 (60%) | 2 (50%) |

| Female | 18 (37.5%) | 5 (33.3%) | 5 (35.7%) | 6 (26%) | 2 (50%) | |

| Etiology of liver disease | HVB | 26 (54.1%) | 6 (26%) | 5 (35.7%) | 12 (80%) | 1 (25%) |

| HVC | 11 (22.9%) | 5 (33.3%) | 4 (28.5%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| HVD | 14 (29%) | 4 (26%) | 4 (28.5%) | 6 (26%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Alcoholic | 9 (18.75%) | 5 (33.3%) | 2 (14.2%) | 1 (6.6%) | 1 (25%) | |

| HCC | 7 (14.5%) | 1 (6.6%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (26%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Others | 7 (14.5%) | 1 (6.6%) | 3 (21.4%) | 1 (6.6%) | 2 (50%) | |

| Arterial lactate (mmol/L) | 2.77 ± 1.22 | 1.2 ± 0.24 | 2.39 ± 0.36 | 3.68 ± 0.41 | 6.6 ± 1.15 | |

| INR | 1.75 ± 0.39 | 1.66 ± 0.26 | 1.52 ± 0.18 | 1.7 ± 0.25 | 3.23 ± 1.36 | |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 165 ± 45 | 174 ± 50 | 177 ± 42 | 152 ± 44 | 144 ± 51 | |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 407 ± 77 | 385 ± 75 | 405 ± 88 | 416 ± 62 | 462 ± 67 | |

| Intraoperative bleeding (mL) | 4550 ± 3200 | 3260 ± 1800 | 3380 ± 1790 | 5106 ± 3600 | 11370 ± 6370 | |

| Length of stay in the ICU (days) | 8.85 ± 3.7 | 6.6 ± 1.65 | 8.15 ± 3.05 | 8.53 ± 2.37 | 21 ± 10.5 | |

| Mortality (at 30 days) | 6 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (13.3%) | 4 (100%) |

HVB – Hepatitis virus B; HVC – Hepatitis virus C; HVD – Hepatitis virus D; INR – International normalized ratio; HCC – Hepatocellular carcinoma; ICU – Intensive care unit

The etiology of liver disease was divided as follows: 54.1% (n = 26) were infected with HBV, 22.9% (n = 11) were infected with HCV, 29% (n = 14) were infected with HBV and HBD, alcoholic cirrhosis was found in 18.75% of cases (n = 9), 14.5 % suffered from hepatocarcinoma and in 14.5% of cases (n = 7) there were other causes of cirrhosis.

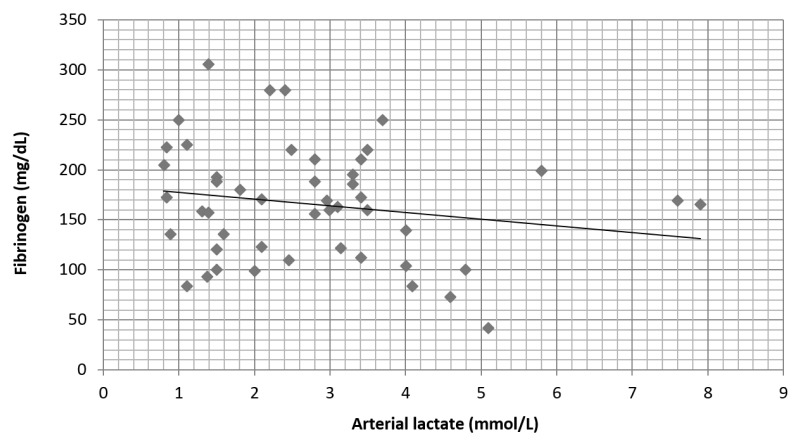

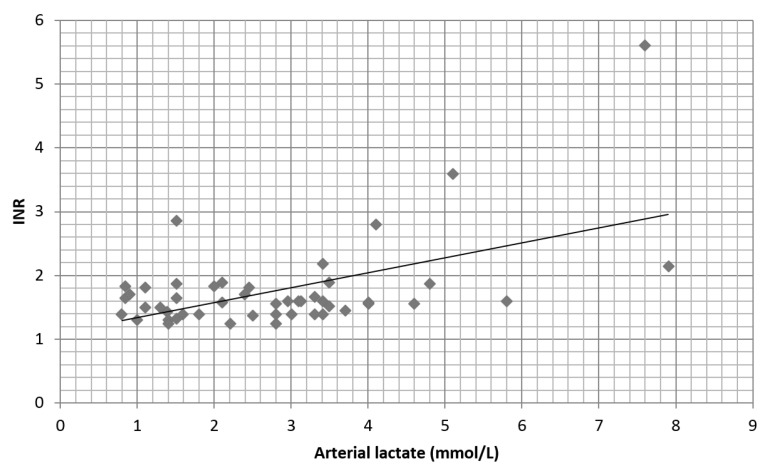

Preoperative fibrinogen values did not influence the arterial lactate at the end of surgery (Figure 1). A moderate correlation (r = 0.45) was found between preoperative coagulation time (INR) and the arterial lactate level mainly above value of 5 mmol/L (Figure 2).

Fig. 1.

Preoperative fibrinogen does not correlate with the arterial lactate levels at the end of the surgery (r = −0.2)

Fig. 2.

Correlation between preoperative INR and postoperative lactate levels. There is a moderate positive correlation (r = 0.45)

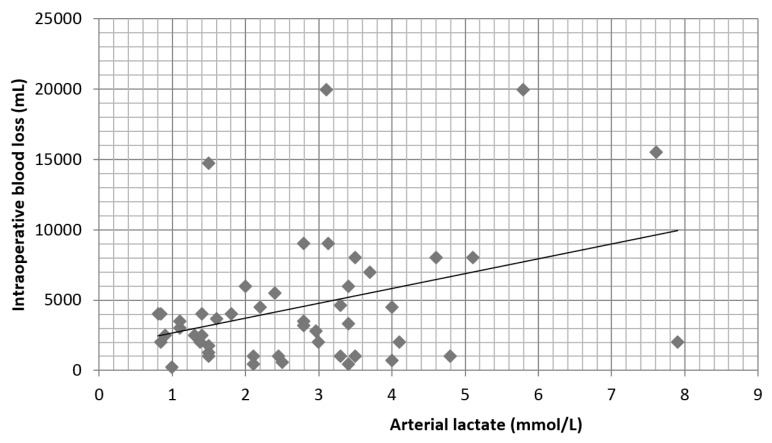

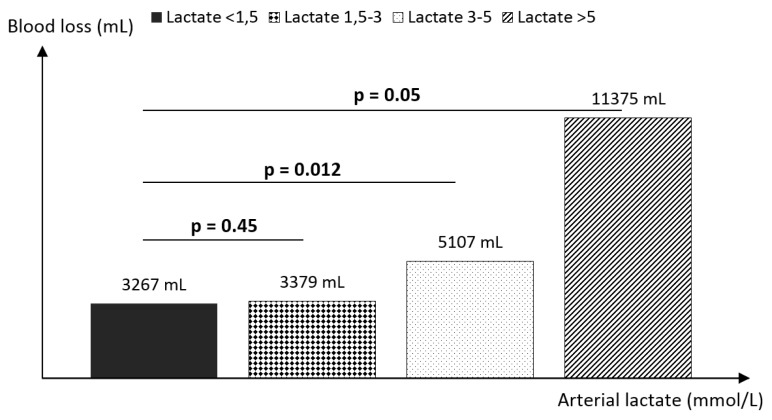

The mean duration of surgery was 407 ± 77 minutes, with the shortest time of 240 minutes. The mean intraoperative blood loss was 4550 ± 3200 ml, ranging from 500 ml to 20,000 ml. The mean arterial lactate levels at the end of surgery were 2.77 ± 1.22 mmol/L (0.84–7.9) and were increased above the normal value of 1.5 mmol/L in 68.75% of patients. Group 1 had a mean arterial lactate level of 1.2 ± 0.24 mmol/L, group 2 – 2.39 ± 0.36 mmol/L, group 3 – 3.68 ± 0.41 mmol/L and group 4 – 6.6 ± 1.15 mmol/L. Intraoperative blood loss correlates (r = 0.52) with the lactate at the end of surgery (Figure 3). Lactate levels above 3 mmol/L were associated with high intraoperative blood loss, more than 5000 ml: group 3 (p = 0.012) and group 4 (p = 0.05) (Figure 4). Major complications including acute kidney injury, need for emergency surgery during ICU stay or primary graft disfunction were observed only in patients with lactate levels > 1.5 mmol/L (18.2%).

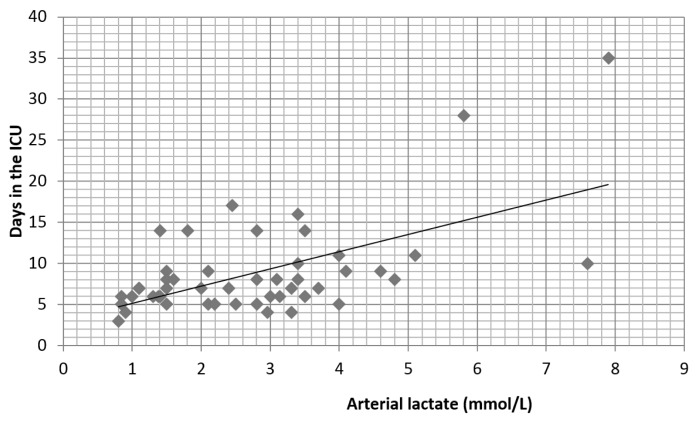

Fig. 3.

Correlation between the lactate level and intraoperative blood loss (r = 0.52)

Fig. 4.

Subgroup analysis of the arterial lactate level and intraoperative blood loss. High intraoperative blood loss can be observed in patients with lactate levels above 3 mmol/L

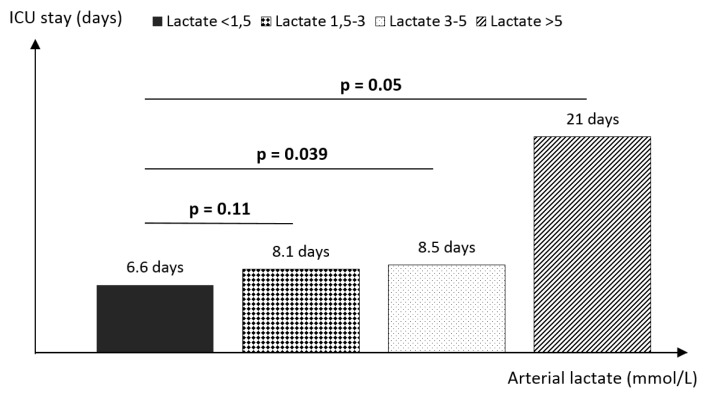

The mean length of PACU stay was 8.85 ± 3.7 days, ranging from 3 to 35 days. There is a positive correlation (r = 0.65) between lactate levels and length of stay in the ICU (Figure 5). Lactate levels in group 3 (p = 0.039) and group 4 (p = 0.05) were associated with a longer PACU stay. The mean length of stay was 8.53 ± 2.37 days in group 3 and 21 ± 10.5 days in group 4 compared to 6.6 ± 1.65 days in those patients with normal lactate levels (Figure 6).

Fig. 5.

Correlation between the lactate level and length of stay in the ICU (r = 0.65)

Fig. 6.

The relationship between the arterial lactate level and length of stay in the ICU. The higher the lactate levels at the end of surgery, the higher the ICU stay

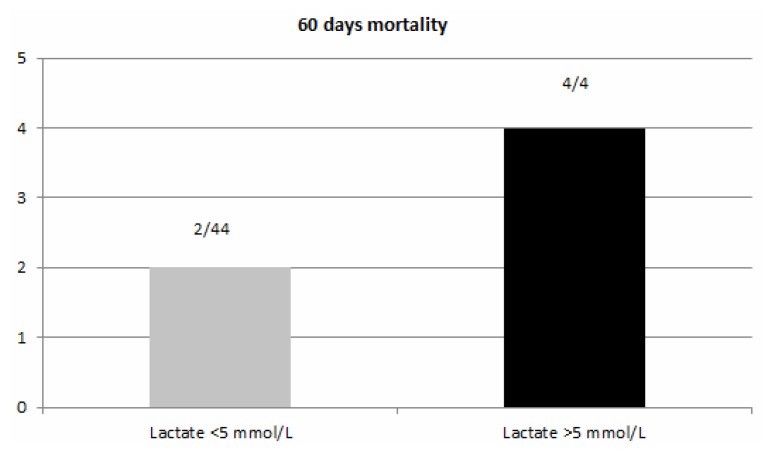

The global 60 days mortality was 12.5%. In the first two groups (arterial lactate level less than 3 mmol/L) no death was recorded in these patients. In the groups with arterial lactate less than 5 mmol/L mortality was 4.5% in comparison with the 100% mortality in the group with arterial lactate level above 5 mmol/L (p = 0.05) (Figure 7).

Fig. 7.

Mortality at 2 months. In the group with lactate above 5 mmol/L, mortality was 100%, compared with the 4.5% mortality in the group with lactate below 5 mmol/L (p = 0.05). The global mortality was 12.5% (6/48 patients)

Discussion

Outcomes after hepatic transplantation have significantly improved over the last few decades [8, 9]. Despite the fact that no single factor is solely responsible, advances in surgical and anaesthetic techniques, better understanding of hepatic physiology and improvement in perioperative management have all been contributory [10–12]. The majority of postoperative management issues after liver transplantation are unique and require an extended understanding of liver metabolism and the pathophysiology of liver disease [13].

On the other hand, liver transplantation is a major complicated procedure with high intra and postoperative risks. Having an objective criteria that might assist you through the postoperative outcome is priceless.

The main findings of this study are that higher lactate levels at the end of the hepatic transplantation are associated with an increased risk of mortality, an increased PACU length of stay and renal and liver dysfunction. The correlation is independent from other preoperative variables such as the recipient’s age, duration of surgery, INR and fibrinogen levels prior to surgery. These findings support those of an earlier study by demonstrating the association of arterial lactate at the end of surgery with renal and hepatic dysfunction and length of stay in addition to mortality [14].

The strongest associations demonstrated were between the lactate concentration and intraoperative blood loss, length of stay in the PACU and 60 days mortality. The intraoperative blood loss is one of the main reasons for the increase in arterial lactate level during hepatic transplantation. There seems to be a threshold level of end of surgery lactate of approximately 5 mmol/L above which, the risk of 60 days mortality rises rapidly.

It was also observed that preoperative INR and fibrinogen as markers of hepatic synthesis do not correlate with the rise in lactate at the end of the liver transplantation.

Our study has several limitations. A potential weakness of this study is that details of pressor agents were not recorded, which could affect the lactate concentration. Precise data regarding intravenous fluid type and volume were not taken into account. Another weakness could be represented by the patients’ comorbidities (diabetus mellitus, renal impairment) which were not taken into consideration but can affect the results. We should also take into account the relatively low number of patients included in the study, compared to other studies on the same subject.

Nevertheless hepatic transplantation is a major process and many variables come into play in the outcome and the success of the procedure.

In conclusion these results are of great value in our practice as it may be possible to use the lactate at the end of LT to predict the patient’s evolution in the postoperative period. Patients with a lactate of less than 1.5 mmol/L have low rates of mortality and organ dysfunction. The correlation of lactate above 3 mmol/L with blood loss, PACU length of stay and mortality may help us prepare customised postoperative management with innovative results.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Nothing to declare

References

- 1.Murthy TVSP. Transfusion support in liver transplantation. Indian J Anaesth. 2007;51:13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. [accessed 2014.04.1]. Available at www.srtr.org.

- 3.Santori G, Andorno E, Antonucci A, Morelli N, Bottino G, Mondello R, et al. Potential predictive value of the MELD score for short-term mortality after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:533–534. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.03.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jo YY, Choi YS, Joo DJ, Yoo YC, Nam SG, Koh SO, et al. Pretransplant mortality predictors in living and deceased donor liver transplantation. J Chin Med Assoc. 2014;77:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Begliominl B, De Wolf A, Freeman J, Kang Y. Intraoperative lactate levels can predict graft function after liver transplantation. Anesthesiology. 1989;71:180. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiggans MG, Starkie T, Shahtahmassebi G, Woolley T, Birt D, Erasmus P, et al. Serum arterial lactate concentration predicts mortality and organ dysfunction following liver resection. Perioper Med (Lond) 2013;2:21. doi: 10.1186/2047-0525-2-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macquillan GC, Seyam MS, Nightingale P, Neuberger JM, Murphy N. Blood lactate but not serum phosphate levels can predict patient outcome in fulminant hepatic failure. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1073–1079. doi: 10.1002/lt.20427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belghiti J, Hiramatsu K, Benoist S, Massault P, Sauvanet A, Farges O. Seven hundred forty-seven hepatectomies in the 1990s: an update to evaluate the actual risk of liver resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:38–46. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarnagin WR, Gonen M, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Ben-Porat L, Little S, et al. Improvement in perioperative outcome after hepatic resection: analysis of 1,803 consecutive cases over the past decade. Ann Surg. 2002;236:397–406. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000029003.66466.B3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melendez JA, Arslan V, Fischer ME, Wuest D, Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, et al. Perioperative outcomes of major hepatic resections under low central venous pressure anesthesia: blood loss, blood transfusion, and the risk of postoperative renal dysfunction. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:620–625. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan WH, Hummel BW, McClelland RN. Reduction in the morbidity and mortality of major hepatic resection. Experience with 52 patients. Am J Surg. 1982;144:740–743. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90561-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neuberger J. The introduction of MELD-based organ allocation impacts 3-month survival after liver transplantation by influencing pretransplant patient characteristics. Transpl Int. 2009;22:979–981. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wrighton LJ, O’Bosky KR, Namm JP, Senthil M. Postoperative management after hepatic resection. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;3:41–47. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2012.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe I, Mayumi T, Arishima T, Takahashi H, Shikano T, Nakao A, et al. Hyperlactemia can predict the prognosis of liver resection. Shock. 2007;28:35–38. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e3180310ca9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]