Abstract

Background

Few studies have assessed long-term effects of particular matter with aerodynamic diameter < 2.5μm (PM2.5) on mortality for causes of cancer other than the lung; we assessed the effects on multiple causes. In Hong Kong most people live and work in urban or suburban areas with high-rise buildings. This facilitates estimation of PM2.5 exposure of individuals taking into account height of residence above ground level for assessment of the long-term health effects with sufficient statistical power.

Methods

We recruited 66,820 persons who were ≥65 in 1998-2001 and followed up for mortality outcomes till 2011. Annual concentrations of PM at their residential addresses were estimated using PM2.5 concentrations measured at fixed-site monitors, horizontal-vertical locations, and satellite data. We used Cox regression model to assess the hazard ratio (HR) of mortality for cancer per 10 μg/m3 increase of PM2.5.

Results

PM2.5 was associated with increased risk of mortality for all causes of cancer (HR 1.22 [95% CI: 1.11–1.34]), and for specific cause of cancer in upper digestive tract (1.42 [1.06–1.89]), digestive accessory organs (1.35 [1.06–1.71]), in all subjects; breast (1.80 [1.26–2.55]) in females; lung (1.36 [1.05–1.77]) in males.

Conclusions

Long-term exposures to PM2.5 is associated with elevated risks of cancer at various organs.

Impact

This study is particularly timely in China where compelling evidence is needed to support pollution control policy to ameliorate the health damages associated with economic growth.

Keywords: air pollution, cohort, elderly, Hong Kong, particulate matter

Introduction

Emissions from transportation and power generation are the major sources of carcinogenic hydrocarbons and heavy metals in particulate matter (PM) (1). Long-term exposure to PM has been associated with mortality mainly from cardiopulmonary causes and lung cancer but there have been few studies showing an association with mortality from other cancers (2–11). Two main biological mechanisms to explain PM-associated cancer mortality have been postulated: first an effect of oxidative stress induced by PM on epithelial cells to produce reactive oxygen species that can damage DNA, proteins and lipids (12); and second an effect of inflammation induced directly or indirectly by PM leading to production of chemokines and cytokines to trigger angiogenesis allowing epithelial invasion of metastatic tumor cells and then survival of the invading malignant cells in distant organs (13). It is plausible that PM-associated carcinogenic risk could appear in organs other than the nasal cavities and lungs but there are few epidemiological studies addressing the postulation. This was a prospective cohort study; the methods before taking into account of floor level in estimation of the exposure and results on mortality for all-natural and cardio-respiratory causes have been published (14). In this study we assessed associations of mortality for various causes of cancer with long-term exposure to PM.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and individual information

18 Elderly Health Centres were established to deliver health examinations and primary care services for older adults in Hong Kong by the Elderly Health Service of the Department of Health of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, that aimed to promote the health of elderly population in each district and to enhance selfcare ability so as to minimize illness and disability. Nurses and doctors of the Elderly Health Centre that located in each of the 18 districts in Hong Kong provides health assessment, using standardized and structured interviews, and comprehensive clinical examinations. Information on socio-demographic, lifestyles, and disease history was collected, as described in a previous study using the data collected by the Elderly Health Service (15). This study covered all 66,820 enrollees from July 1998 to December 2001, which was recruited on voluntary basis, accounting for 9% of the 65 or older population at the baseline year (the sampling fractions ranging from 6.6 to 17.5% of the population older than 65 years of age in each district) (16). The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster and the ethics committee of the Department of Health.

Follow-up

Vital status and causes of death was ascertained by record linkage to death registration in Hong Kong using the unique Hong Kong identity card number. The last date of follow-up or censor date was December 31, 2011. Causes of death were routinely coded using International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9th Revision before 2001 and 10th Revision in or after 2001. Most of the Hong Kong residents died in hospital, ensuring accurate ascertainment of cause of death. Those whose vital status could not be determined were assumed to be alive.

Mortality outcomes

The cause of death was coded by both ICD-9 and ICD-10 over the study period from 1998, and was based on the underlying cause of death according to the underlying etiology or injury that initiated the chain of morbid events leading directly to death. The mortality causes considered in this study were subcategories of cancer, which accounted for at least 100 deaths. They were: all malignant neoplasms or cancers ICD10:C00-C99 (or ICD9:140-209). Subcategories of cancers included were: all digestive organs C15-C26 (150-159) which was subdivided into (i) upper digestive tract C15-16 (150-151) including esophagus and stomach, (ii) lower digestive tract C17-21 (152-154) including small intestine, colon, rectum, appendix, and anus, and (iii) accessory organs C22-25 (155-157) including liver, gall bladder and pancreas; lung including trachea C33-C34 (162); breast C50 (174); female genital C51-C58 (179-184); male genital C60-C63 (185-187); urinary C64-C68 (188-189); and lympho-hematopoietic C81-C96 (200-209). To assess the specificity, we assessed the causes of poisoning and injuries (S00–Y98) mortality which was considered to be unrelated to PM exposure.

Individual, ecological and environmental covariates

On the basis of the data from a standardized questionnaire, we included individual covariates of age, gender, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, exercise frequency, education level, and personal monthly expenditure. On the basis of census statistics in 197 land areas, by the Tertiary Planning Units (16), we included ecological covariates in percentage of older subjects (aged 65+), percentage with tertiary education and monthly domestic household income. From 18 districts of Hong Kong, we included environmental covariates in percentage of smokers (aged 15+) for indication of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in each year. On the basis of ad hoc survey, we included ground radon levels (kBqm-3) in 1×1 km grid of a data map (17–19).

Exposure estimation model

We calculated annual mean concentrations (μg/m3) of particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter < 2.5 um (PM2.5) based on data from 5 stations run by the Environmental Protection Department which has monitored hourly concentrations of the pollutants by tapered element oscillating microbalance from 1998 until 2011. In all the locations, we obtained their geospatial height above the mean sea level and the satellite information in 1×1 km grids of surface extinction coefficients (20–22). Then we fitted regression models to estimate PM2.5 concentrations using surface extinction coefficients and inverse geospatial height (i.e. 1/height) of the residential location above the mean sea level as independent variables.

We geocoded all residential addresses of the subjects, and matched them with the surface extinction coefficients data. We calculated the vertical height of each address based on the floor number. Using the above mentioned exposure model, we estimated the annual mean concentrations of PM2.5 in each residential location. We then compared the estimates with the results independently obtained from a deterministic model based on street canyon geometry, traffic census, air pollution, and meteorological data for an area where the data were available (23).

Statistical Analysis

For each organ-specific cancer mortality data set, we used Cox proportional hazards model to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) of mortality (n=60,273) for every 10 μg/m3 increase of long-term exposure to PM2.5 concentration with adjustment for individual, ecological and environmental covariates after excluding subjects (9.8%) with missing data in any covariates that were previously mentioned. We used time-on-study from the baseline as timescale and the estimated exposure in the subjects' recruitment year (between 1998 and 2001) to represent long-term exposure. To control for competing diseases and to assure detection of long-term associations, we excluded deaths due to other causes and deaths that occurred within 3 years from the baseline year respectively. We stratified the data by ever and never smoker and tested for the difference by an interaction term in the model, respectively for male and female. We performed the sensitivity analysis by excluding height of address from sea level in the exposure estimation, by using current annual mean PM2.5 as time-varying variable in the Cox model, and by competing risks model instead of excluding deaths from competing causes (24), or by excluding subjects with self-reported pre-existing respiratory and cardio-metabolic diseases at baseline. Death records were the primary follow-up information in this study (with average of 10.3 years and range 0-13 years of follow-up) but those which might have lost to follow-up due to change in address or migration were not traceable. Among the non-missing records until the last follow-up year, there were 16% of them who did not appear in any formal records of adverse health events nor in any questionnaire interviews in the last 3 years, which might be due to loss to follow-up. Therefore we also performed the sensitivity analysis by excluding these 16% potential loss to follow-up subjects from the analysis. Further sensitivity analyses were perform to exclude deaths within 5 or 7 years, subjects who had moved during the follow-up period or had been hospitalized during 1998-2000, to take account of diseases which may take longer than 3 years for the incubation period, the effect of moving address and the effect of mixing with prevalent cases, respectively. Cox models were performed using the command PHREG in Statistical Analysis System (SAS) 9.2. We plotted the relationship between PM2.5 and deaths from all cancers using the natural splines command COXPH in R 3.0.1 with two degrees of freedom. As a sensitivity analysis, we also used models with random effects set at the intercepts to take account of possible intra-district correlations (25, 26).

Results

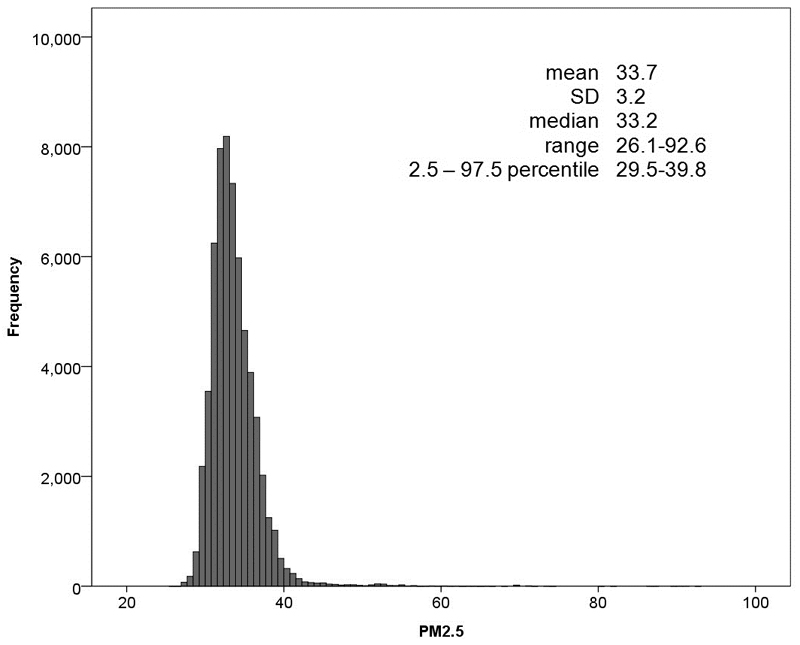

In the exposure models for PM2.5 (R2=0.47) both inverse height (p<0.001) and surface extinction coefficients (p<0.01) were significant predictors. Comparison of the empirically estimated PM concentrations with those estimated from deterministic model for street canyon yielded good validation measures (Supplementary Table S1). The estimated PM2.5 mean concentration (2.5 – 97.5 percentile) in the baseline year at individual residential locations was 33.7 (29.5–39.8) μg/m3 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of PM2.5 (μg/m3).

The figure depicts the frequency of subjects (y-axis) in each class interval (1 µg/m3 of PM2.5) against PM2.5 concentration in µg/m3 units (x-axis).

Subjects who were exposed to cleaner air quality tended to be younger, have a higher BMI and be never-smokers, frequent exercisers, better educated, lower in personal expenditure, and be located in areas with fewer older people, higher levels of education, higher income and higher radon levels (all P Values<0.01). Significant covariates identified in the Cox regression model of cancer mortality were older, male, underweight, ever smoked, less educated, and lived in a community with younger, less educated and with more smoking subjects (Table 1).

Table 1.

Hazard Ratios Adjusted for Individual, Ecological and Environmental Covariates for All Cancer Mortality Due to Long-Term Exposure to PM2.5

| Characteristics | HR | 95% CI | No. of deaths per 1000 person- years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per 10 µg/m3 increase of PM2.5 | ||||

| Mean±SD: 33.7±3.2; IQR: 3.3; Median (range): 33.2 (26.1-92.6) |

1.22 | 1.11, 1.34 | ||

| Individual: | ||||

| Age (year) | 1.09 | 1.09, 1.10 | ||

| Gender | Male as ref. | 10.8 | ||

| Female | 0.68 | 0.63, 0.74 | 6.3 | |

| BMI quartiles | Q2-Q3 (21.6-26.3) as ref. | 7.5 | ||

| Q1 (<21.6) | 1.09 | 1.02, 1.18 | 9.3 | |

| Q4 (>26.3) | 1.05 | 0.98, 1.13 | 7.1 | |

| Smoking | Never-smoked as ref. | 6.1 | ||

| Quitted | 1.49 | 1.37, 1.61 | 10.9 | |

| Current | 2.33 | 2.13, 2.54 | 14.2 | |

| Exercise (days/week) | 0.98 | 0.96, 1.01 | ||

| Education | Secondary or above as ref. | 7.5 | ||

| Primary | 1.07 | 0.98, 1.16 | 8.5 | |

| Below primary | 1.08 | 0.99, 1.19 | 7.4 | |

| Monthly expenditure (US$), | <128 | 0.97 | 0.87, 1.09 | 7.3 |

| 128-384 | 1.07 | 0.98, 1.16 | 8.0 | |

| ≥385 as ref. | 7.4 | |||

| Ecological: | ||||

| Age≥65 | 0.99 | 0.98, 1.00 | ||

| Education as tertiary level | 0.99 | 0.98, 1.00 | ||

| Income/month ≥US$1,923 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.01 | ||

| Environmental: | ||||

| Tobacco smoke (as % of smokers) | 1.21 | 1.05, 1.40 | ||

| Radon (kBqm-3) | 0-40 as ref. | 8.1 | ||

| 41-100 | 1.06 | 0.97, 1.15 | 7.6 | |

| ≥101 | 1.08 | 0.98, 1.20 | 8.0 | |

Note: 47,594 subjects were included in the model. 4,531 of them died of cancers.

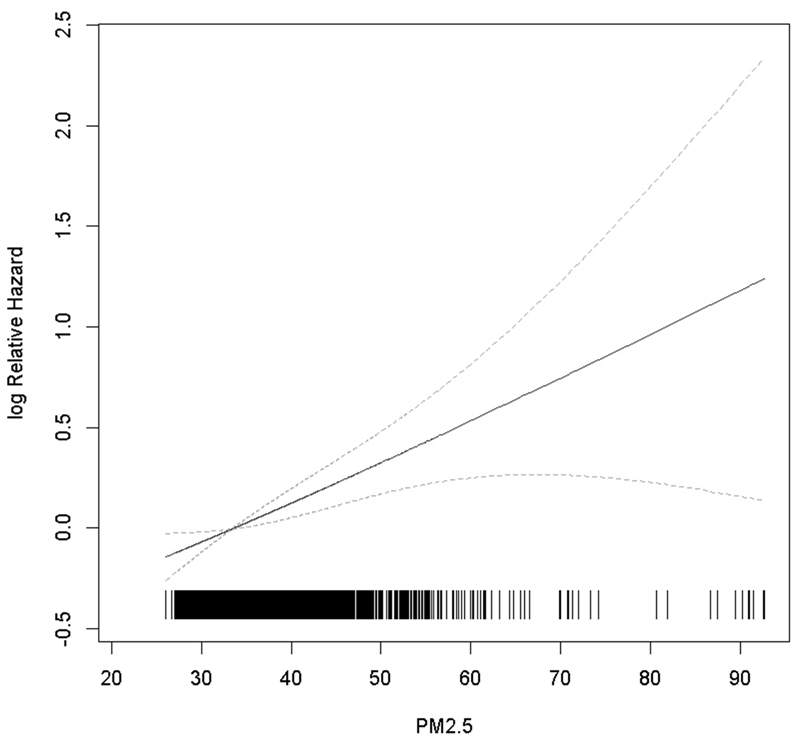

PM2.5 was associated with all-cancer mortality (HR = 1.22, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.11, 1.34) as well as cause-specific cancer mortality including all digestive organs (HR = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.42), upper digestive tract (HR = 1.42, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.89), and accessory digestive organs (HR = 1.35, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.71). In female, the associations were shown in breast (HR = 1.80, 95% CI: 1.26, 2.55) and genital organs (HR = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.17, 2.54) (Table 2). PM2.5 was not significantly (P>0.05) associated with external causes. A linear concentration-response relationship between PM2.5 and all-cancer mortality was shown (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Hazard Ratios for Mortality of All Natural Causes and Specific Cancers per 10 µg/m3 of PM2.5

| ICD10 | Causes of mortality | na | HRb | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A00-R99 | All natural causes | 14,398 | 1.13 | 1.08, 1.19 | <0.001 |

| C00-C97 | All malignant | 4,531 | 1.22 | 1.11, 1.34 | <0.001 |

| C15-26 | All digestive organs | 1,734 | 1.22 | 1.05, 1.42 | 0.01 |

| C15-16 | Upper digestive tract | 323 | 1.42 | 1.06, 1.89 | 0.02 |

| C17-21 | Lower digestive tract | 719 | 1.01 | 0.79, 1.30 | 0.91 |

| C22-25 | Accessory organs | 676 | 1.35 | 1.06, 1.71 | 0.01 |

| C33-34 | Lung | 1,408 | 1.14 | 0.96, 1.36 | 0.14 |

| C50 | Breast | 111 | 1.80 | 1.26, 2.55 | 0.001 |

| C51-58 | Female genital | 138 | 1.73 | 1.17, 2.54 | 0.006 |

| C60-63 | Male genital | 143 | 1.02 | 0.51, 2.04 | 0.96 |

| C64-68 | Urinary | 155 | 0.98 | 0.58, 1.64 | 0.93 |

| C81-96 | Lympho-hematopoietic | 310 | 1.29 | 0.86, 1.95 | 0.21 |

n=number of deceased subjects

Hazard ratios (HR) were adjusted for all covariates as in Table 1.

Figure 2. The pattern of association between all-cancer mortality risk and long-term exposure to PM2.5 (μg/m3).

Solid line (95%CI: dashed line) based on fully adjusted model in Table 1 with natural spline on 2 degrees of freedom. The marks above the x-axis shows the measurements with the crowdedness indicating the distribution of PM2.5 concentration.

In the stratified analysis, PM2.5 (per 10 μg/m3 increase) was associated with mortality due to lung cancers (HR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.77) among male subgroup (Table 3). The HRs in the sensitivity analyses (Table 4) were consistent to those in the main analyses in terms of magnitude and direction of deviation from the null effect estimate.

Table 3.

Stratification Analysis: Hazard Ratios for Mortality of Cancer per 10 µg/m3 of PM2.5 in Male and Female Subjects

| a) Male | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | Never smoker | Ever smoker | Interaction | |||||||||||

| Causes of Mortality | n | HR | 95% CI | P Value | n | HR | 95% CI | n | HR | 95% CI | P value | |||

| All malignant | 2043 | 1.31 | 1.13, 1.51 | <0.001 | 553 | 1.23 | 0.90, 1.67 | 1490 | 1.33 | 1.13, 1.56 | 0.75 | |||

| All digestive organs | 791 | 1.29 | 1.01, 1.65 | 0.04 | 261 | 1.23 | 0.83, 1.83 | 530 | 1.32 | 0.98, 1.78 | 0.94 | |||

| Upper digestive tract | 176 | 1.46 | 0.98, 2.18 | 0.06 | 54 | 1.49 | 0.79, 2.81 | 122 | 1.44 | 0.88, 2.35 | 0.31 | |||

| Lower digestive tract | 311 | 1.21 | 0.81, 1.81 | 0.35 | 105 | 1.13 | 0.61, 2.07 | 206 | 1.23 | 0.76, 2.01 | 0.46 | |||

| Accessory organs | 298 | 1.28 | 0.83, 1.96 | 0.26 | 101 | 1.09 | 0.55, 2.18 | 197 | 1.37 | 0.81, 2.32 | 0.98 | |||

| Lung | 677 | 1.36 | 1.05, 1.77 | 0.02 | 100 | 1.19 | 0.52, 2.74 | 577 | 1.37 | 1.05, 1.78 | 0.41 | |||

| Male genital | 143 | 1.02 | 0.51, 2.04 | 0.96 | 64 | 0.75 | 0.22, 2.61 | 79 | 1.16 | 0.49, 2.78 | 0.86 | |||

| Urinary | 87 | 1.03 | 0.48, 2.24 | 0.93 | 22 | 0.41 | 0.04, 3.84 | 65 | 1.14 | 0.56, 2.35 | 0.23 | |||

| Lympho-hematopoietic | 124 | 1.65 | 0.93, 2.94 | 0.09 | 49 | 0.97 | 0.36, 2.63 | 75 | 2.05 | 1.05, 4.02 | 0.59 | |||

| b) Female | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | Never smoker | Ever smoker | Interaction | |||||||||||

| Causes of Mortality | n | HR | 95% CI | P Value | n | HR | 95% CI | n | HR | 95% CI | P value | |||

| All malignant | 2488 | 1.17 | 1.03, 1.32 | 0.02 | 2047 | 1.17 | 1.02, 1.34 | 441 | 1.12 | 0.82, 1.52 | 0.38 | |||

| All digestive organs | 943 | 1.16 | 0.96, 1.41 | 0.13 | 821 | 1.17 | 0.96, 1.44 | 122 | 1.01 | 0.59, 1.71 | 0.26 | |||

| Upper digestive tract | 147 | 1.37 | 0.91, 2.05 | 0.13 | 127 | 1.35 | 0.89, 2.04 | 20 | 1.25 | 0.36, 4.27 | 0.52 | |||

| Lower digestive tract | 408 | 0.88 | 0.64, 1.23 | 0.46 | 354 | 0.91 | 0.64, 1.28 | 54 | 0.72 | 0.26, 2.02 | 0.63 | |||

| Accessory organs | 378 | 1.37 | 1.05, 1.80 | 0.02 | 332 | 1.36 | 1.01, 1.84 | 46 | 1.39 | 0.79, 2.45 | 0.58 | |||

| Lung | 731 | 0.99 | 0.77, 1.27 | 0.92 | 523 | 1.01 | 0.76, 1.36 | 208 | 0.95 | 0.61, 1.47 | 0.99 | |||

| Breast | 111 | 1.80 | 1.26, 2.55 | 0.001 | 99 | 1.66 | 1.10, 2.50 | 12 | 7.14 | 2.01, 25.4 | 0.10 | |||

| Female genital | 138 | 1.73 | 1.17, 2.54 | 0.006 | 126 | 1.65 | 1.07, 2.55 | 12 | 2.48 | 1.09, 5.61 | 0.53 | |||

| Urinary | 68 | 0.89 | 0.45, 1.79 | 0.75 | 53 | 1.03 | 0.54, 1.96 | 15 | 0.35 | 0.03, 4.18 | 0.30 | |||

| Lympho-hematopoietic | 186 | 1.12 | 0.62, 2.02 | 0.70 | 161 | 1.17 | 0.62, 2.19 | 25 | 0.84 | 0.26, 2.75 | 0.99 | |||

Table 4.

Sensitivity Analyses: Hazard Ratios for Mortality of All Cancers per 10 µg/m3 of PM2.5

| Sensitivity | n | HR | 95%CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without using geospatial height in exposure estimation | 4,546 | 1.20 | 1.06, 1.36 | 0.005 |

| Time-varying annual mean exposure instead of baseline year exposure | 4,514 | 1.21 | 1.10, 1.33 | <0.001 |

| Without control of competing diseases | 4,531 | 1.21 | 1.10, 1.33 | <0.001 |

| Exclusion of subjects as potential loss to follow-up | 4,531 | 1.23 | 1.12, 1.35 | <0.001 |

| Exclusion of deaths for the first 5 years | 3,697 | 1.23 | 1.11, 1.37 | <0.001 |

| Exclusion of deaths for the first 7 years | 2,706 | 1.14 | 1.04, 1.25 | 0.015 |

| Exclusion of subjects who had moved during the following up period | 4,192 | 1.22 | 1.11, 1.35 | <0.001 |

| Exclusion of subjects who had hospitalization record in 1998-2000 | 2,687 | 1.25 | 1.12, 1.41 | <0.001 |

| Exclusion of subjects with self-reported pre-existing respiratory or cardio-metabolic diseases at baseline | 2,582 | 1.20 | 1.05, 1.37 | 0.006 |

| Adjustment for alcohol intake | ||||

| All malignant | 4,531 | 1.22 | 1.11, 1.34 | <0.001 |

| All digestive organs | 1,734 | 1.22 | 1.05, 1.42 | 0.01 |

| Random effects with adjustment of autocorrelation at planning areas (i.e. Tertiary Planning Units) | 4,531 | 1.22 | 1.11, 1.34 | <0.001 |

| Competing risks | 4,531 | 1.14 | 1.04, 1.25 | 0.007 |

Discussion

We showed that in older people, cancer mortality risks were associated with long-term exposure to particulate air pollutants in a typical Asian city, Hong Kong, where the people dwell mainly in high-rise buildings. We demonstrated carcinogenic risks of PM2.5 in multiple organs and tissues using the approach for a single prospective cohort. There are few studies in the literature comparing PM2.5 associations on cancer mortality among different organs or tissues. We found stronger associations with PM2.5 in the upper digestive tract and accessory organs, and breast than among all-cancer or all-digestive organs. While most of our findings on specific cancers were not reported in the American Cancer Society study, our observations are consistent with the American Cancer Society study in a way that the excess risks of specific causes were larger than those of less specific causes (9). Our HR per 10 μg/m3 PM2.5 for female genital cancer and for breast cancer were about 40-50% higher than the reported relative risk (1.20 and 1.19, respectively) in an ecological study of all ages in Taiwan (27, 28). When compared with the American Cancer Society study, our HR per 10 μg/m3 PM2.5 for all-digestive organs and for male lung cancer was fairly similar to their respective HR of 1.20 and 1.43, adjusted for individual covariates and components of social factors (9).

A hypothesis for an explanation at the molecular level of the carcinogenic effects of PM could be in terms of defects in DNA repair function and replication (29). Effects of oxidative stress due to air pollution have also been shown in biomarker studies (30). However, pathological explanations for specific cancer mortality are rare. For digestive systems the hypothesized mechanisms include inflammations of gut lining epithelial cells following ingestion, alterations in immune response and effects on gut microbiota (31). These hypotheses may be connected to aerosolized pollutants which are trapped by mucus and swallowed, eventually passing through the whole digestive tract and affecting the epithelial cells and the gut microbiota. A large-scale European case-control study of household wood burning on esophageal cancer (32), and an ecological Spanish study of industrial metallic aerosols on gallbladder and pancreas cancers have also indicated similar associations of air pollutants with cancer of the upper digestive tract and accessory organs (33).

A human experimental study on metal species in thyroid cancer have hypothesized environmental contamination as a possible factor in explaining the thyroid pathology (34). Though the evidence is still insufficient, the literature has given some support to our findings on the PM-related cancer risks on multiple sites including digestive system, lung, breasts, genital organs, and lympho-hematopoietic tissues.

Most studies of the long-term associations of PM estimated proxy exposure of individuals at region of residence, either using geospatial/dispersion modeling or satellite information (5, 9, 35–38). However, estimation of chronic health associations of PM using intra-region spatial variation in the present study has resulted in similar hazard ratios to those studies relying on contrasts of multiple region-wide average exposures. The smaller estimates in the latter were likely due to the greater exposure measurement errors which led to underestimation of the pollution-related health burden (9). A California study showed that associations within cities are similar as between cities and the difference in exposure metrics had little impact on the risk estimates for PM2.5 (39). We found that there were no differences between estimates before and after controlling for intra-district correlations with random effect modeling. This result was supported by another US study on incidence of cardiovascular events, incorporating a random effect term for between-city and within-city effects (40).

There were limitations in the present study. First, we did not address the associations of multi-pollutant exposure, indoor air pollution, chemical and physical-size components of PM2.5. The roles of PM2.5 cannot be disentangled from the other environmental pollutants. Second, we did not assess the contribution of genetic factors, metastasis, nor cancer-inhibitory inflammation mechanism for the association, and because of that we were not able to determine the effects of PM on susceptible groups and on cancer development (13). Third, the short period of the study, which does not allow assessment of health outcomes with long latency period, is another limitation. However the participants could have already been living in the same address before enrollment, since the 5-year moving rates in the older population were consistent and less than 15% in the past 10-15 years (41), only 9.3% of the subjects were found not residing in the same address during the around 10 years of follow-up and the estimates were robust to exclusion of movers from the analysis. Fourth, most of the subjects (93%) were retired or not working anymore. Yet, their employment history was not known and any previous occupational exposure was not accounted for. Fifth, the daily activities of the subjects were not assessed in details by questionnaires. However, in our sensitivity analysis using annual mean exposure at year of comparison in model should have taken account of this. Outdoor activities (for example, travelling to other parts of the city) or indoor activities (such as the use of air purifiers) which would affect the exposure level of PM2.5 were not adjusted for. Further studies to take these into account are needed. Sixth, stage of cancer at diagnosis was not available in our data, which may affect the choice of treatment method and hence survival from premature death (42). However, since trends of PM in different geographic areas were stable over the study period, the effect estimates may not be affected substantially.

Last but not least, selection bias may be an issue due to voluntary nature in the subject recruitment. Volunteers who were more aware of the “new” provision of elderly health service by the government could tend to be more conscious in seeking health care service, which would potentially lead to underestimation of the risk of PM in this study.

For older people who dwell in a city with a dense population and high-rise buildings in Asia, long-term exposures to particulate air pollutants are associated with mortality from all cancers combined with a linear concentration response relationship. Associations were also found between PM2.5 and various specific cancers, including cancer in lung, all digestive organs, breasts and genital organs. The magnitudes of risks are comparable with those of other similar studies, providing further evidence to strengthen causality and support health economic assessments of cancer-related deaths attributable to air pollution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Hong Kong Special Administration Region departments including the Department of Health (Elderly Health Services) for cohort data, Census and Statistics Department for mortality data and Environmental Protection Department for PM2.5 data. We thank The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology for satellite information and Department of Geography in The University of Hong Kong for geocoding. We also thank Prof KK Cheng of the University of Birmingham, United Kingdom for valuable comments.

Financial support: C.M. Wong had been awarded the Wellcome Trust [#094330/Z10/Z]. H. Tsang, H.K. Lai, K.P. Chan, and Q.S. Zheng received the above grant.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Valavanidis A, Fiotakis K, Vlachogianni T. Airborne particulate matter and human health: toxicological assessment and importance of size and composition of particles for oxidative damage and carcinogenic mechanisms. J Environ Sci Health C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev. 2008;26:339–62. doi: 10.1080/10590500802494538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson JO, Thundiyil JG, Stolbach A. Clearing the air: a review of the effects of particulate matter air pollution on human health. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8:166–75. doi: 10.1007/s13181-011-0203-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pope CA, 3rd, Dockery DW. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: lines that connect. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2006;56:709–42. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2006.10464485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pope CA, 3rd, Burnett RT, Thurston GD, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Krewski D, et al. Cardiovascular mortality and long-term exposure to particulate air pollution: epidemiological evidence of general pathophysiological pathways of disease. Circulation. 2004;109:71–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000108927.80044.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Ma R, Pope CA, 3rd, Krewski D, Newbold KB, et al. Spatial analysis of air pollution and mortality in Los Angeles. Epidemiology. 2006;16:727–36. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000181630.15826.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pope CA, 3rd, Burnett RT, Turner MC, Cohen A, Krewski D, Jerrett M, et al. Lung cancer and cardiovascular disease mortality associated with ambient air pollution and cigarette smoke: shape of the exposure-response relationships. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:1616–21. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cesaroni G, Badaloni C, Gariazzo C, Stafoggia M, Sozzi R, Davoli M, et al. Long-term exposure to urban air pollution and mortality in a cohort of more than a million adults in Rome. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:324–31. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heinrich J, Thiering E, Rzehak P, Krämer U, Hochadel M, Rauchfuss KM, et al. Long-term exposure to NO2 and PM10 and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a prospective cohort of women. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70:179–86. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2012-100876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krewski D, Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Ma R, Hughes E, Shi Y, et al. Extended follow-up and spatial analysis of the American Cancer Society study linking particulate air pollution and mortality. Res Rep Health Eff Inst. 2009:5–114. discussion 115-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raaschou-Nielsen O, Andersen ZJ, Beelen R, Samoli E, Stafoggia M, Weinmayr G, et al. Air pollution and lung cancer incidence in 17 European cohorts: prospective analyses from the European Study of Cohorts for Air Pollution Effects (ESCAPE) Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:813–22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loomis D, Grosse Y, Lauby-Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, et al. The carcinogenicity of outdoor air pollution. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1262–3. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70487-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Risom L, Møller P, Loft S. Oxidative stress-induced DNA damage by particulate air pollution. Mutat Res. 2005;592:119–37. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–44. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong CM, Lai HK, Tsang H, Thach TQ, Thomas GN, Lam KB, et al. Satellite-Based Estimates of Long-Term Exposure to Fine Particles and Association with Mortality in Elderly Hong Kong Residents. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:1167–72. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schooling CM, Lam TH, Li ZB, Ho SY, Chan WM, Ho KS, et al. Obesity, physical activity, and mortality in a prospective chinese elderly cohort. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1498–504. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.14.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Census and Statistics Department. Hong Kong 2001 population census TAB on CD-ROM. [cited 2014 Feb 27];2002 Available from: http://www.censtatd.gov.hk/major_projects/2001_population_census/

- 17.Census and Statistics Department. Hong Kong 2004 population and household statistics analysed by district council district. [cited 2015 May 28]; Available from: http://www.censtatd.gov.hk/hkstat/sub/sp150.jsp?productCode=B1130301.

- 18.Census and Statistics Department. Thematic household survey Report No. 48. [cited 2015 May 28];2011 Available from: http://www.censtatd.gov.hk/hkstat/sub/sp140.jsp?productCode=B1130201.

- 19.Tung S. Radon potential mapping in Hong Kong [dissertation] The University of Hong Kong; Hong Kong: 2010. [cited 2015 Sep 29]. Available from: http://hub.hku.hk/handle/10722/133479. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li CC, Lau AKH, Mao JT, Chu DA. Retrieval, validation, and application of the 1-km aerosol optical depth from MODIS measurements over Hong Kong. IEEE T Geosci Rem. 2005;43:2650–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai HK, Ho SY, Wong CM, Mak KK, Lo WS, Lam TH. Exposure to particulate air pollution at different living locations and respiratory symptoms in Hong Kong -- an application of satellite information. Int J Environ Health Res. 2010;20:219–30. doi: 10.1080/09603120903511119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai HK, Tsang H, Thach TQ, Wong CM. Health impact assessment of exposure to fine particulate matter based on satellite and meteorological information. Environ Sci Process Impacts. 2014;16:239–46. doi: 10.1039/c3em00357d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chapmen PS. The outdoor horizontal and vertical variations of respirable suspended particulate concentrations within a densely urban environment in Hong Kong - application of a box and plume dispersion model (airGIS/OSPM) [dissertation]; Hong Kong. The University of Hong Kong: 2012. [cited 2015 Sep 29]. Available from: http://hub.hku.hk/handle/10722/161544;jsessionid=5ECC34093DFA65E34A57B0E766AD9E38. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beyersmann J, Schumacher M, Allignol A. Competing Risks and Multistate Models with R. New York. NY: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burnett R, Ma R, Jerrett M, Goldberg MS, Cakmak S, Pope CA, III, et al. The spatial association between community air pollution and mortality: A new method of analyzing correlated geographic cohort data. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:375–80. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109s3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma R, Krewski D, Burnett RT. Random effects Cox models: A Poisson modelling approach. Biometrika. 2003;90:157–69. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hung LJ, Chan TF, Wu CH, Chiu HF, Yang CY. Traffic air pollution and risk of death from ovarian cancer in Taiwan: fine particulate matter as a proxy marker. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2012;75:174–82. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2012.641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hung LJ, Tsai SS, Chen PS, Yang YH, Liou SH, Wu TN, et al. Traffic Air Pollution and Risk of Death from Breast Cancer in Taiwan: Fine Particulate Matter as a Proxy Marker. Aerosol and Air Quality Research. 2012;12:275–82. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehta M, Chen LC, Gordon T, Rom W, Tang MS. Particulate matter inhibits DNA repair and enhances mutagenesis. Mutat Res. 2008;657:116–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mills NL, Donaldson K, Hadoke PW, Boon NA, MacNee W, Cassee FR. Adverse cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2009;6:36–44. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beamish LA, Osornio-Vargas AR, Wine E. Air pollution: An environmental factor contributing to intestinal disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:279–86. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sapkota A, Zaridze D, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Mates D, Fabiánová E, Rudnai P. Indoor air pollution from solid fuels and risk of upper aerodigestive tract cancers in central and eastern Europe. Environ Res. 2013;120:90–5. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.García-Pérez J, López-Cima MF, Pérez-Gómez B, Aragonés N, Pollán M, Vidal E, et al. Mortality due to tumours of the digestive system in towns lying in the vicinity of metal production and processing installations. Sci Total Environ. 2010;408:3102–12. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boulyga SF, Loreti V, Bettmer J, Heumann KG. Application of SEC-ICP-MS for comparative analyses of metal-containing species in cancerous and healthy human thyroid samples. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2004;380:198–203. doi: 10.1007/s00216-004-2699-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atkinson RW, Carey IM, Kent AJ, van Staa TP, Anderson HR, Cook DG. Long-term exposure to outdoor air pollution and incidence of cardiovascular diseases. Epidemiology. 2013;24:44–53. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318276ccb8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hart JE, Garshick E, Dockery DW, Smith TJ, Ryan L, Laden F. Long-term ambient multipollutant exposures and mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:73–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1903OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gan WQ, Koehoorn M, Davies HW, Demers PA, Tamburic L, Brauer M. Long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution and the risk of coronary heart disease hospitalization and mortality. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:501–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kloog I, Coull BA, Zanobetti A, Koutrakis P, Schwartz JD. Acute and chronic effects of particles on hospital admissions in New-England. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Beckerman BS, Turner MC, Krewski D, Thurston G, et al. Spatial analysis of air pollution and mortality in California. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:593–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201303-0609OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller KA, Siscovick DS, Sheppard L, Shepherd K, Sullivan JH, Anderson GL, et al. Long-term exposure to air pollution and incidence of cardiovascular events in women. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:447–58. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hong Kong Census 1991, 1996, 2001. Main reports. [cited 2015 Sep 8]; Available from: http://www.censtatd.gov.hk/hkstat/

- 42.Hu H, Dailey AB, Kan H, Xu X. The effect of atmospheric particulate matter on survival of breast cancer among US females. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;139:217–26. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2527-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.