Abstract

Background

Understanding how patient–physician communication affects patients’ medication experience would help hypertensive patients maintain their regular long-term medication therapy. This study aimed to examine whether patient–physician communication (information and interpersonal treatment) affects patients’ medication experience directly or indirectly through changing medication adherence for each of the two communication domains.

Methods

A self-administered cross-sectional survey was conducted for older patients who had visited a community senior center as a member. Two communication domains were assessed using two subscales of the Primary Care Assessment Survey. Medication adherence and experience were measured using the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale and a five-point Likert scale, respectively. Mediatory effects were assessed via Baron and Kenny’s procedure and a Sobel test.

Results

Patient–physician communication had a positive prediction on patients’ medication experience (β=0.25, P=0.03), and this was fully mediated by medication adherence (z=3.62, P<0.001). Of the two components of patient–physician communication, only informative communication showed a mediatory effect (z=2.21, P=0.03).

Conclusion

Patient–physician communication, specifically informative communication, had the potential to improve patients’ medication experience via changes in medication adherence. This finding can inform health care stakeholders of the mediatory role of medication adherence in ensuring favorable medication experience for older hypertensive patients by fostering informative patient–physician communication.

Keywords: patient medication experience, medication adherence, patient–physician communication, patient-centered practice, patient-reported outcome, mediation

Introduction

For hypertensive patients who take antihypertensive medication, it is quite a burden to take medication daily for their life. Therefore, it is important for them to have favorable experience while taking the medication, to achieve greater success in blood pressure control. Favorable medication experience definitely results from the medication prescribed according to clinical guidelines. However, it can be also augmented with good patient–physician communication. Extensive research has shown that patient–physician communication, defined as interpersonal exchange of information between patients and physicians, positively affects patients’ health experience,1–6 as it establishes a strong bond of trust,7,8 affects patients’ perceptions of and attitudes toward treatment,9,10 and improves patients’ self-management skills.11–13 Therefore, it is likely that patient–physician communication has the potential to help patients have favorable experience on medication therapy.

With the growing emphasis on patient-centered practice, many researchers have examined the role of patient–physician communication. Earlier studies report that patient–physician communication exerts a positive impact on medication adherence.11,14 However, a study has yet to examine what effect the patient–physician communication would have on patient experience regarding the medication. Given the positive communication’s effect on medication adherence, its effect on patients’ medication experience is likely to occur indirectly through making changes in medication adherence; that is, medication adherence likely mediates the effect of patient–physician communication on patient medication experience. An understanding of the ways in which patient–physician communication improves patient medication experience could enhance the design of effective communication strategies for better medication experience and outcomes.

The current study aimed to examine whether patient–physician communication predicts patients’ medication experience among older hypertensive patients. Specifically, this study aimed to examine whether medication adherence mediates the communication’s effect on patient medication experience for two domains of patient–physician communication (informative communication and interpersonal treatment).

Methods

Study design and procedures

We employed a cross-sectional design and conducted a two-part survey of a convenience sample of 300 individuals who were members of one of seven community centers for seniors in a metropolitan area with one million people or more of a southeastern state of the United States. Three senior centers were located in city while four were in the suburbs. The first part of the survey was to collect views of all seniors, without restricting to those taking antihypertensive medications, on health care applicability of a hypothetical set of patients’ reviews and ratings of medication experience,15 and the second part was to collect actual ratings of patient experience occurring while taking antihypertensive medications. The number of study participants who would complete the second part of the survey was estimated to be at least 180, given that 60% of the older people in the US were taking at least one medication for control of hypertension.16,17 The directors of senior centers were contacted to arrange a date of survey administration on which many seniors were able to visit the centers. The survey was conducted between August and December 2013. During each visit, the director announced the survey to the visitors in order to help recruit volunteers for survey participation. Two research assistants checked volunteers for English communication and explained the purpose of the study and their rights as participants. Those who completed the self-administered survey received a $20 grocery gift card to compensate them for their time and effort. The University of Tennessee Health Science Center Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the survey and this study along with its informed consent. All participants were provided written informed consent before starting the survey, but had an option not to sign (the review board asked for the removal of the requirement to obtain written informed consent from all participants because of the concern that it might reveal their identity).

Measurements and scales

Patient characteristics

We collected data regarding patients’ age, sex, educational level, race, income, residential status, marital status, and comorbidity. Household income was measured via an open-ended question and classified into four groups based on the income criteria for the state of Tennessee.18 We measured comorbidity using the Charlson Comorbidity Index based on a list of conditions for participants to check off if doctors had ever told they had any of the conditions, and classified the patients into three groups according to their scores (0, 1, and ≥2).

Patient–physician communication

Patient–physician communication was measured using the Communication and Interpersonal Treatment subscales of the Primary Care Assessment Survey (PCAS); the PCAS measures characteristics of primary care using 11 subscales, five of which concern the patient–physician relationship. The Communication subscale of six items measures the quality of informative communication exchanged for the relationship, and the Interpersonal Treatment subscale of five items measures the quality of interpersonal treatment in the relationship (Table 1). Responses are provided using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (“very poor” or “always,” depending on the item) to 6 (“excellent” or “never,” depending on the item). Total scores for each subscale (when normalized) ranged from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher levels of informative communication and interpersonal treatment.19 The sum of the two subscale scores represented the overall quality of patient–physician communication. Both the Communication and Interpersonal Treatment subscales combined demonstrated excellent reliability, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.95.

Table 1.

Informative and interpersonal domains of patient–physician communication

| Categories | Questions |

|---|---|

| PCAS – Communication (informative domain) | Thoroughness of your doctor’s questions about your symptoms and how you are feeling |

| Attention your doctor gives to what you have to say | |

| Doctor’s explanations of your health problems or treatments that you need | |

| Doctor’s instructions about symptoms to report and when to seek further care | |

| Doctor’s advice and help in making decisions about your care | |

| How often do you leave your doctor’s office with unanswered questions? | |

| PCAS – Interpersonal Treatment (interpersonal domain) | Amount of time your doctor spends with you |

| Doctor’s patience with your questions or worries | |

| Doctor’s friendliness and warmth toward you | |

| Doctor’s caring and concern for you | |

| Doctor’s respect for you |

Notes: Reproduced from Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR, et al. The Primary Care Assessment Survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Medical Care. 1998;36(5):728–739. © 1998 Lippincott-Raven Publishers. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3767409?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. Promotional and commercial use of the material in print, digital or mobile device format is prohibited without the permission from the publisher Wolters Kluwer. Please contact healthpermissions@wolterskluwer.com for further information.19

Abbreviation: PCAS, Primary Care Assessment Survey.

Medication adherence

Medication adherence was measured using the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale. The scale is a valid self-report questionnaire consisting of eight questions related to patients’ medication adherence. Cronbach’s α was 0.83 for patients diagnosed with essential hypertension, and the scale’s predictive validity has been assessed via association with blood pressure readings, attitude, social support, techniques for coping with stress, knowledge regarding medical conditions and treatment, and patients’ satisfaction with care provided.20,21

Patient medication experience

Medication experience was measured using participants’ ratings for the hypertensive medications that they had been taking. Participants rated their experience with regard to six aspects of medication (effectiveness, side effects, ease of use, food interaction, cost of medication, and overall) using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“poor”) to 5 (“excellent”). Each patient was asked to rate their experience for up to four antihypertensive medications. The mean of the overall ratings for each patient was computed as the measure for the patient’s overall medication experience.

Statistical analysis

Frequency distribution was used to describe the patients’ characteristics. To determine the existence of a mediator, the data were fit to three multiple linear regression models, which were adjusted for patients’ characteristics, as suggested by Baron and Kenny.22 Furthermore, Sobel tests were conducted to examine any mediatory effects.23 All regression coefficients (β) were standardized to compare their unique contributions; that is, regression analyses were carried out after converting all variables to those with mean of 0 and variance of 1. All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Participants’ characteristics

Of the 191 participants, 82% were >65 years of age and 77.5% were female (Table 2). More than a half (59.6%) were Non-Hispanic White and 37.7% were Non-Hispanic Black. Most participants were educated to high school level or higher (96.9%), with middle or lower socioeconomic status (95.8%). Approximately one third of participants had a Charlson Comorbidity Index score or ≥2 (31.4%) and 40% had a score of 0.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics (N=191)

| Participant characteristics | Na | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 190 | ||

| ≤64 | 34 | 18.0 | |

| 65–75 | 93 | 48.7 | |

| ≥76 | 63 | 33.0 | |

| Sex | 191 | ||

| Male | 43 | 22.5 | |

| Female | 148 | 77.5 | |

| Educational level | 189 | ||

| High school or lower | 6 | 3.1 | |

| High school graduate | 63 | 33.0 | |

| Some college | 72 | 37.7 | |

| College graduate or higher | 48 | 25.1 | |

| Race | 191 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 110 | 59.6 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 72 | 37.7 | |

| Othersb | 9 | 4.7 | |

| Income | 168 | ||

| Low | 80 | 41.9 | |

| Lower middle | 34 | 17.8 | |

| Middle | 46 | 24.1 | |

| High | 8 | 4.2 | |

| Residential status | 191 | ||

| Alone | 83 | 43.5 | |

| With spouse | 72 | 37.7 | |

| Othersc | 36 | 18.6 | |

| Marital status | 191 | ||

| Married or separated | 72 | 37.7 | |

| Divorced | 42 | 22.0 | |

| Widowed | 65 | 34.0 | |

| Never married | 12 | 6.3 | |

| Comorbidity | 191 | ||

| 0 | 76 | 39.8 | |

| 1 | 55 | 28.8 | |

| 2 | 60 | 31.4 |

Notes:

There are missing values because some participants did not answer every question.

Others include Asian, Indian, and Alaskan natives.

Others include living with parents, children, siblings, companions, or pets, and living in a retirement community.

Patient–physician communication, medication adherence, and medication experience

Participants’ mean score for patient–physician communication was 153.64 (standard deviation [SD] =30.80) out of a possible 200. When each PCAS subscale was examined further, mean scores for the Communication and Interpersonal Treatment subscales were 77.07 (SD =16.07) and 76.58 (SD =15.60), respectively. The mean score for medication adherence was 6.94 (SD =1.48) out of a possible 8, and the mean score for medication experience was 4.50 (SD =0.86) out of a possible 5. For all measures, higher scores indicated superior performance (Table 3).

Table 3.

Description of patient–physician communication, medication adherence, and medication experience

| Self-reported measures | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Physician–patient communication | 153.64 (30.80) | 70–200 |

| PCAS – Communication | 77.07 (16.07) | 25–100 |

| PCAS – Interpersonal Treatment | 76.58 (15.60) | 36.67–100 |

| Medication adherence | 6.94 (1.48) | 1.25–8 |

| Medication experience | 4.50 (0.86) | 1–5 |

Abbreviations: PCAS, Primary Care Assessment Survey; SD, standard deviation.

Effect of patient–physician communication on patients’ medication experience

Three regression models were developed using Baron and Kenny’s procedure, to determine whether patient–physician communication predicted patients’ medication experience directly or indirectly via medication adherence. If the prediction occurred indirectly, we could conclude that it was mediated by medication adherence. In the first model, patient–physician communication and patients’ medication experience were entered as the independent and dependent variables, respectively, and the results indicated that patient–physician communication was a significant predictor of patients’ medication experience (β=0.16, P=0.03; Table 4). In the second model, patient–physician communication and patients’ medication adherence were entered as the independent and dependent variables, respectively, and the results indicated that patient–physician communication was a significant predictor of medication adherence (β=0.25, P<0.001). In the third model, patient–physician communication and medication adherence were both entered as independent variables, and medication experience was entered as the dependent variable; the results showed that medication adherence remained a significant predictor of patients’ medication experience (β=0.19, P=0.02), but patient–physician communication did not (β=0.11, P=0.15). The Sobel test also revealed that medication adherence mediated the effect of patient–physician communication on patient medication experience (z=3.62, P<0.001).

Table 4.

Baron and Kenny’s procedure for the mediatory role of medication adherence

| Independent variables | Dependent variables

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient medication experience

|

Patient medication adherence

|

Patient medication experiencec

|

|

| β (P) | β (P) | β (P) | |

| Patient–physician communication | 0.16* (0.03) | 0.25** (<0.00) | 0.11 (0.15) |

| Patient medication adherence | N/A | N/A | 0.19* (0.02) |

| Age (years) | |||

| ≤64 | Reference | ||

| 65–75 | 0.06 (0.58) | 0.14 (0.18) | 0.03 (0.76) |

| ≥76 | −0.04 (0.69) | 0.25* (0.02) | −0.09 (0.42) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | Reference | ||

| Female | 0.07 (0.36) | 0.06 (0.43) | 0.06 (0.43) |

| Education | |||

| High school or lower | Reference | ||

| High school or graduate | 0.30 (0.15) | 0.02 (0.90) | 0.29 (0.15) |

| Some college | 0.27 (0.20) | −0.12 (0.53) | 0.29 (0.16) |

| College graduate or higher | 0.33 (0.09) | −0.03 (0.88) | 0.33 (0.08) |

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | Reference | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | −0.08 (0.35) | −0.14 (0.07) | −0.05 (0.55) |

| Othersa | −0.07 (0.36) | −0.11 (0.12) | −0.05 (0.52) |

| Income | |||

| Low | Reference | ||

| Lower middle | 0.02 (0.80) | 0.04 (0.59) | 0.01 (0.88) |

| Middle | 0.07 (0.43) | 0.10 (0.23) | 0.05 (0.55) |

| High | −0.03 (0.69) | 0.01 (0.93) | −0.03 (0.68) |

| Residential | |||

| Alone | |||

| With spouse | 0.08 (0.67) | −0.02 (0.90) | 0.08 (0.65) |

| Othersb | −0.10 (0.19) | 0.08 (0.30) | −0.12 (0.13) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married or separated | Reference | ||

| Divorced | 0.06 (0.72) | −0.06 (0.69) | 0.07 (0.66) |

| Widowed | 0.07 (0.68) | 0.07 (0.69) | 0.06 (0.74) |

| Never married | −0.24* (0.03) | −0.17 (0.11) | −0.21 (0.06) |

| Comorbidity class | |||

| 0 | Reference | ||

| 1 | 0.07 (0.37) | −0.03 (0.65) | 0.08 (0.33) |

| 2 | 0.01 (0.86) | 0.00 (0.99) | 0.01 (0.85) |

| R2 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.23 |

Notes:

Others include Asian, Indian, and Alaskan natives.

Others include living with parents, children, siblings, companions, or pets, and living in a retirement community.

The regression model includes the independent variable, patient medication adherence, while the earlier one does not. Variables marked as N/A are indicative of not being included in the regression model.

P<0.05,

P<0.001.

Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable.

Informative communication versus interpersonal treatment

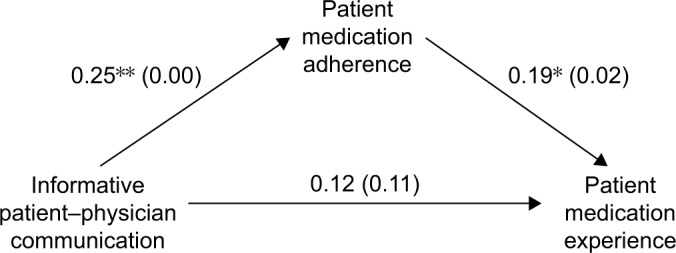

The influence of patient–physician communication on patient medication experience was examined separately for each communication domain, and only informative communication exerted a significant effect on patient medication experience (β=0.17, P=0.02; Table 5). Furthermore, the communication’s effect on patient medication experience was fully mediated by medication adherence, in that the effect of patient–physician communication was no longer significant with the inclusion of medication adherence (β=0.12, P=0.11; Figure 1) in the regression model. The Sobel test confirmed the existence of the mediator (z=2.21, P=0.03).

Table 5.

Baron and Kenny’s procedure for the mediatory role of medication adherence for two communication domains

| Independent variables | Dependent variables

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient medication experience

|

Patient medication experience

|

Patient medication adherence

|

Patient medication experiencec

|

|

| β (P) | β (P) | β (P) | β (P) | |

| Patient–physician communication | ||||

| Interpersonal domain | 0.14 (0.06) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Informative domain | N/A | 0.17* (0.02) | 0.25** (<0.00) | 0.12 (0.11) |

| Patient medication adherence | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.19* (0.02) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤64 | Reference | |||

| 65–75 | 0.06 (0.59) | 0.06 (0.57) | 0.14 (0.17) | 0.03 (0.74) |

| ≥76 | −0.05 (0.63) | −0.03 (0.76) | 0.26 (0.12) | −0.08 (0.46) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | Reference | |||

| Female | 0.07 (0.34) | 0.07 (0.37) | 0.06 (0.43) | 0.06 (0.44) |

| Education | ||||

| High school or lower | Reference | |||

| High school or graduate | 0.30 (0.14) | 0.29 (0.15) | 0.01 (0.95) | 0.28 (0.16) |

| Some college | 0.27 (0.20) | 0.26 (0.20) | −0.13 (0.51) | 0.29 (0.16) |

| College graduate or higher | 0.33 (0.09) | 0.32 (0.09) | −0.03 (0.86) | 0.33 (0.09) |

| Race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Reference | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | −0.08 (0.33) | −0.07 (0.38) | −0.13 (0.09) | −0.05 (0.57) |

| Othersa | −0.07 (0.32) | −0.07 (0.38) | −0.11 (0.13) | −0.05 (0.54) |

| Income | ||||

| Low | Reference | |||

| Lower middle | 0.02 (0.78) | 0.02 (0.79) | 0.04 (0.56) | 0.01 (0.88) |

| Middle | 0.07 (0.39) | 0.07 (0.44) | 0.10 (0.23) | 0.05 (0.57) |

| High | −0.03 (0.69) | −0.03 (0.68) | 0.00 (0.95) | −0.03 (0.67) |

| Residential | ||||

| Alone | Reference | |||

| With spouse | 0.07 (0.71) | 0.09 (0.62) | −0.01 (0.97) | 0.09 (0.61) |

| Othersb | −0.10 (0.19) | −0.10 (0.19) | 0.08 (0.30) | −0.12 (0.13) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married or separated | Reference | |||

| Divorced | 0.04 (0.79) | 0.07 (0.65) | −0.04 (0.77) | 0.08 (0.62) |

| Widowed | 0.06 (0.72) | 0.08 (0.65) | 0.07 (0.65) | 0.07 (0.71) |

| Never married | −0.25* (0.03) | −0.23* (0.04) | −0.16 (0.12) | −0.20 (0.07) |

| Comorbidity class | ||||

| 0 | Reference | |||

| 1 | 0.07 (0.40) | 0.08 (0.33) | −0.03 (0.73) | 0.08 (0.31) |

| 2 | 0.01 (0.87) | 0.02 (0.82) | 0.01 (0.92) | 0.02 (0.83) |

| R2 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.23 |

Notes:

Others include Asian, Indian, and Alaskan natives.

Others include living with parents, children, siblings, companions, or pets, and living in a retirement community.

The regression model includes the independent variable, patient medication adherence, while the earlier one does not. Variables marked as N/A are indicative of not being included in the regression model.

P<0.05,

P<0.001.

Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable.

Figure 1.

Mediation effect of patient medication adherence between informative patient–physician communication and patient medication experience.

Notes: *P<0.05, **P<0.001. Values before parentheses are standardized beta coefficients and values within parentheses represent P-values.

In summary, patient–physician communication significantly predicted patients’ medication experience among older patients with hypertension. However, the significant prediction existed through mediation by medication adherence. Furthermore, the mediation occurred only for informative communication, but not for interpersonal treatment.

Discussion

This study found that patient–physician communication positively predicted patient medication experience. A number of studies support this finding.6,24–26 For example, communication that involves attentiveness and empathy27,28 and promotes patient engagement29 has been identified as a positive predictor of patients’ treatment satisfaction. Indeed, good communication is key to establishing trusting, caring relationships with patients and motivating them to follow treatment recommendations.

This study further found that the effect of patient–physician communication on patient medication experience was fully mediated by medication adherence. This finding implies that patient–physician communication can improve patient medication experience, but not without producing a positive change in medication adherence. In other words, patient–physician communication needs to emphasize the importance of medication adherence if it intends to help patients to have a positive experience on medication therapy. Considering the importance of medication adherence in bringing patients to positive medication experience, other means of improving medication adherence such as patient counseling and communication technology should be explored.

As for the two domains (informative and interpersonal treatment) of patient–physician communication, only informative communication exerted a positive effect on medication experience, which was fully mediated by medication adherence. It appears that older hypertensive patients are in need of “information,” rather than “interpersonal treatment,” to correctly take antihypertensive medications, a major treatment tool for hypertension. Hypertensive patients face many challenges in adhering to the required medication therapy. Those challenges include the requirement to take the medication daily without breaks, the inability to feel the benefits of medication treatment, long-term side effects, and a strong likelihood of complex medication regimens and polypharmacy.30 Patients facing these challenges need information regarding both why and how they should take their medication. Under these circumstances, informative communication that helps patients to understand how to improve their medication adherence, rather than interpersonal communication that helps them to build trusting, friendly relationships with their physicians, could be more effective in improving their medication adherence.

Limitations

The study was subject to some limitations. First, the findings are not generalizable to other populations, because convenience sampling was used to recruit participants, who were all from a single metropolitan area in a southeastern state of the United States. However, participants’ demographic characteristics were similar to those of individuals in many southeastern states. Second, the study might have erroneously assumed that patients’ medication experience depends on their medication adherence. In fact, the reverse could be true, given that patients are likely to adhere to their medication regimen if their experience of taking the medication is positive. This study assumed that the former is more likely than the latter. Hypertension is an asymptomatic condition where patients cannot feel whether the medication works or not. Patients can tell it works only when their blood pressure is measured. In other words, patients have to adhere to the medication in order to assess their experience with the medication.

Conclusion

In conclusion, patient–physician communication positively predicted older patients’ experience on antihypertensive medication therapy. However, the positive prediction occurred indirectly via changes in medication adherence. Furthermore, of the two domains of communication (informative and interpersonal), only informative communication exhibited the indirect effect on patients’ medication experience that was fully mediated by medication adherence. These findings can inform health care stakeholders of the mediatory role of medication adherence in ensuring favorable medication experience for older hypertensive patients by fostering informative communication between patients and their doctors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Sunghee Tak for her valuable insights on patients’ medication experience and Dr Yazed Alruthia for assisting in survey administration. This work was supported by the University of Tennessee Health Science Center and the Seoul National University Research Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE. Expanding patient involvement in care: effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102(4):520–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-4-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ong LM, De Haes JC, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor–patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(7):903–918. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00155-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bredart A, Bouleuc C, Dolbeault S. Doctor–patient communication and satisfaction with care in oncology. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17(4):351–354. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000167734.26454.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):e001570. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Street RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician–patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(3):295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein RM, Street RL., Jr . Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2007. NIH Publication 07-6225. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mechanic D, Schlesinger M. The impact of managed care on patients’ trust in medical care and their physicians. JAMA. 1996;275(21):1693–1697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson LA, Dedrick RF. Development of the trust in physician scale: a measure to assess interpersonal trust in patient-physician relationships. Psychol Rep. 1990;67(3f):1091–1100. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1990.67.3f.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman DS, Hahn SR, Gelb L, et al. Doctor–patient communication, health-related beliefs, and adherence in glaucoma: results from the glaucoma adherence and persistency study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(8):1320–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shrank WH, Cadarette SM, Cox E, et al. Is there a relationship between patient beliefs or communication about generic drugs and medication utilization? Med Care. 2009;47(3):319. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818af850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zolnierek KBH, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heisler M, Bouknight RR, Hayward RA, Smith DM, Kerr EA. The relative importance of physician communication, participatory decision making, and patient understanding in diabetes self-management. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(4):243–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heisler M, Cole I, Weir D, Kerr EA, Hayward RA. Does physician communication influence older patients’ diabetes self-management and glycemic control? Results from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(12):1435–1442. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.12.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ratanawongsa N, Karter AJ, Parker MM, et al. Communication and medication refill adherence: the Diabetes Study of Northern California. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(3):210–218. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong SH, Lee W, AlRuthia Y. Health care applicability of a patient-centric web portal for patient’s medication experience. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(7):e202. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Heart Association Inc Statistical Fact Sheet; 2013 Update: High Blood Pressure. 2013. [Last accessed June 29, 2017]. Available from: https://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heart-public/@wcm/@sop/@smd/documents/downloadable/ucm_319587.pdf.

- 17.Gu Q, Burt VL, Dillon CF, Yoon S. Trends in antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control among United States adults with hypertension: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001 to 2010. Circulation. 2012;126(17):2105–2114. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.096156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feinauer J. What it takes to be middle class in each state. Deseret News. 2015 Apr 21; [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR, et al. The Primary Care Assessment Survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Med Care. 1998;36(5):728–739. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199805000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens. 2008;10(5):348–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 21.Morisky DE, DiMatteo MR. Improving the measurement of self-reported medication nonadherence: response to authors. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(3):255. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociol Methodol. 1982;13(1982):290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levinson W, Lesser CS, Epstein RM. Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Aff. 2010;29(7):1310–1318. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson JL. Communication about symptoms in primary care: impact on patient outcomes. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11(Suppl 1):s51–s56. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.s-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart MA. Effective physician–patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152(9):1423. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Del Canale S, Louis DZ, Maio V, et al. The relationship between physician empathy and disease complications: an empirical study of primary care physicians and their diabetic patients in Parma, Italy. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1243–1249. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182628fbf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neumann M, Wirtz M, Bollschweiler E, et al. Determinants and patient-reported long-term outcomes of physician empathy in oncology: a structural equation modelling approach. Patient Educ Counsel. 2007;69(1):63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff. 2013;32(2):207–214. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pasina L, Brucato A, Falcone C, et al. Medication non-adherence among elderly patients newly discharged and receiving polypharmacy. Drugs Aging. 2014;31(4):283–289. doi: 10.1007/s40266-014-0163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]