Abstract

Ion channels have been extensively reported as an effector of carbon monoxide (CO). However, the mechanisms of heme-independent CO action are still missing. Because most of ion channels are heterologously expressed on human embryonic kidney cells which are cultured in Fe3+-containing media, CO may act as a small and strong iron chelator to disrupt a putative iron bridge in ion channels and thus to tune their activity. In this review CFTR and Slo1 BKCa channels are employed to discuss the possible heme-independent interplay between iron and CO. Our recent studies demonstrated a high-affinity Fe3+ site at the interface between the regulatory domain and intracellular loop 3 of CFTR. Because the binding of Fe3+ to CFTR prevents channel opening, the stimulatory effect of CO on the Cl− and HCO3− currents across the apical membrane of rat distal colon may be due to the release of inhibitive Fe3+ by CO. In contrast, CO repeatedly stimulates the human Slo1 BKCa channel opening possibly by binding to an unknown iron site because cyanide prohibits this heme-independent CO stimulation. Here, in silico research on recent structural data of the slo1 BKCa channels indicates two putative binuclear Fe2+-binding motifs in the gating ring in which CO may compete with protein residues to bind to either Fe2+ bowl to disrupt the Fe2+ bridge but not to release Fe2+ from the channel. Thus, these two new regulation models of CO, iron releasing from and retaining in the ion channel, may have significant and extensive implications for other metalloproteins.

Keywords: ion channel, metalloprotein, gating, gas regulation, binuclear Fe bowl

Introduction

Carbon monoxide (CO) is emerging an intriguing role in actively regulating ion channels such as voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ (Cav) channels1–2, background tandem P domain K+ (K2p) channels3, large-conductance, voltage- and Ca2+ -activated K+ (BKCa) channels4, epithelial Na+ channels (ENaC)5–6, P2X receptor7, voltage-gated K+ (Kv) channels8, voltage-gated sodium (Nav 1) channels9, and T-type Ca2+ channels10. These ion channels are generally heterologously expressed on human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells. Their exposure to a CO-releasing molecule (CORM-2), tricarbonyl dichlororuthenium (II) dimer ([Ru(CO3)Cl2]2 2), stimulates or inhibits channel activity11–12. Because the HEK cells are cultured in Fe3+-containing media such as Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and there are some trace amount of Fe2+ or Fe3+ in cells under physiological conditions, Fe2+ or Fe3+ may be involved in these events. However, most of experiments were done by using the whole-cell configuration, CO may act as a signal molecule (cellular messenger) to modulate channel activity via several intracellular signal pathways. For example, the products of heme catalyzed by heme oxygenase (HO) have not only CO but also Fe2+ and biliverdin. Which product specifically acts on ion channels are unknown. In addition, CORM-2 may also directly regulate channel activity and have nothing to do with the CO gas. Until now only Slo1 BKCa channels were studied at detail by using the inside-out membrane patch and the CO gas. Because repeated activation of this Slo1 channel by CO is prohibited not by the removal of heme-binding site but by cyanide4, 13, and the non-bonding lone pair of electrons in carbon can render strong transition metal binding to CO, it is possible that CO may bind to a putative Fe site but not to release the Fe ion from the channel. On the other hand, CORM-2 has been reported to evoke the Cl− and HCO3− currents across the apical membrane of rat distal colon14, CO and the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) anion channel in colon may be involved. Because our recent studies indicated an inhibitive Fe3+ site with a high affinity for CFTR15–16, CO may stimulate the CFTR activity by chelating and releasing Fe3+ from the CFTR. Thus, these two case studies on the potential heme-independent interplay between iron and CO in BKCa and CFTR channels may reveal two new regulation modes of CO which will prompt mechanistic understanding of heme-independent action of CO on other ion channels and metalloproteins.

CFTR channel

CFTR, a unique and important member of ATP binding cassette (ABC) superfamily, serves as not an ATP-driven pump but an ATP-gated anion channel. It regulates fluid and electrolyte across epithelial surface and resultant mucociliary clearance in multiple organs including lung, pancreas, liver, sweat duct, intestines and reproductive tract. Genetic mutation-induced dysfunction of human CFTR at the respiratory epithelium causes cystic fibrosis (CF), the most common monogenic inherited disorder among Caucasines. This genetic disease brings about many adult CF patients to be chronically infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Pa) in the CF lung so that resultant biofilm formation enhances antibiotic resistance of Pa by acquiring iron. For example, the most common CF-causing mutation F508del increases iron release by human airway epithelial cells and thus promotes the exuberant formation of antibiotic-resistant biofilms while Fe3+ chelation with deferoxamine or deferasirox or hypothiocyanite prevents Pa biofilm formation and eliminates established biofilms on CF airway cells overexpressing F508del17–19. Because Corr-4a increases F508del-CFTR-mediated chloride secretion in the plasma membrane and reduces biofilm formation without changing the iron concentration in the apical medium20, limiting iron acquisition and increasing CFTR activity on airways may be an attractive therapeutic strategy to reduce Pa biofilm formation.

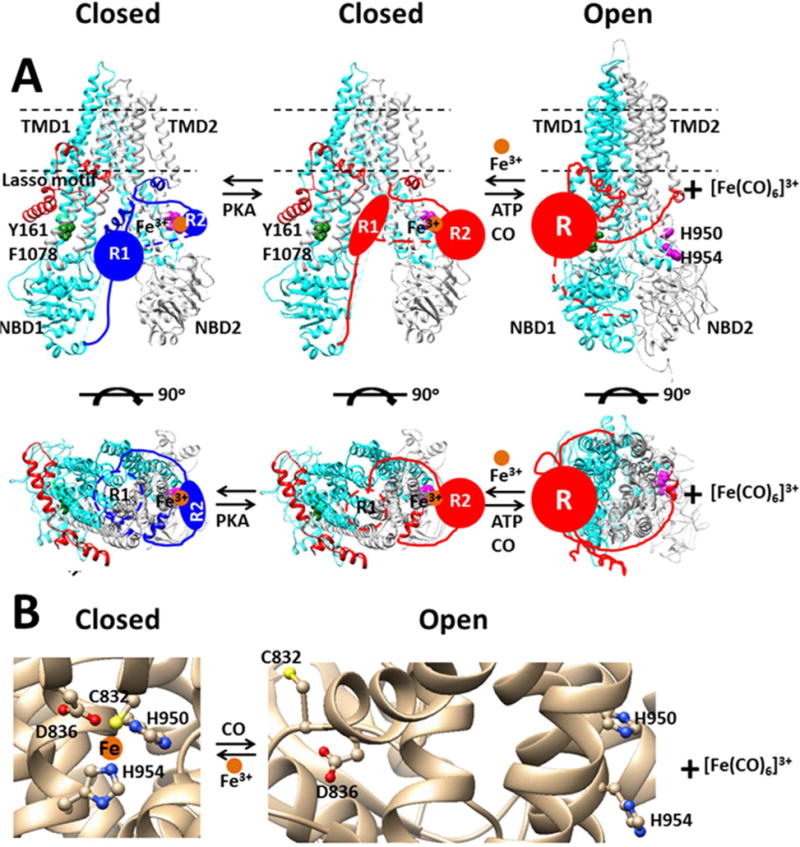

Canonic ABC transporters consist of two copies of a transmembrane domain (TMD) followed by a cytoplasmic nucleotide binding domain (NBD). ATP binding-induced dimerization of two NBDs triggers an inward-to-“outward” gating reorientation of two TMDs to pump a drug out21–22. However, CFTR has a unique unstructured regulatory (R) domain linking NBD1 with TMD2. The early gold-labelled electron microscopy (EM) structure indicated that the R domain is located beside intracellular loops (ICLs) of TMD223. In contrast, recent metal-free cryo-EM structure of human CFTR revealed that the R domain is surrounded by NBD1 and NBD2 and ICLs24. Furthermore, electrophyiological studies showed that the R domain inhibits channel opening not only by preventing the ATP binding-induced NBD1-NBD2 dimerization25–26 but also by interacting with ICL3 via the H-bond, the Fe3+ bridge and the salt bridge15–16, 27–28. Upon phosphorylation by PKA, the R domain promote channel opening by releasing from ICL3 and the NBD1-NBD2 interface for binding to the ICL1-ICL4 interface and the N-terminal of CFTR29, 30–33. Thus, the unphosphorylated R domain may surround TMD2 and NBD2 for channel closure while the phosphorylated R domain may circle both TMDs and NBDs for channel opening (Figure 1). Since there is amount of trace Fe3+ in the cell under the physiological condition, further Fe3+-bound structures of human CFTR are expected. In addition, because Fe3+ inhibits channel opening of CFTR, a Fe3+- chelating potentiator is also helpful to rescue CF mutants. Although curcumin is such a potentiator16, 31, the low bioavailability of curcumin limits its clinical application. On the other hand, although orkambi (lumacaftor 200 mg/ivacaftor 125 mg) has been approved by US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to exploit VX-809 (lumacaftor) to rescue the surface expression of F508del-CFTR in the apical membrane of airway epithelial cells and VX-770 (ivacaftor) to promote channel opening of F508del-CFTR34–35, VX-770 actually diminishes F508del-CFTR cellular stability and the efficacy of VX-80936–37. More importantly, iron-required Pa reduces VX-809-stimulated F508del-CFTR Cl− secretion by airway epithelial cells but VX-770 cannot reverse this reduction38. Because iron chelators such as deferoxamine or deferasirox or hypothiocyanite can prevent Pa biofilm formation while VX-770 cannot17–19, 38, VX-770 may be a weak Fe-chelator and the resultant clinical efficacy of orkambi is weakened. In this regard, more cost-effective Fe-chelating potentiators are necessary to more specifically increase F508del-CFTR chloride secretion by airway epithelial cells and to reduce Pa infection.

Figure 1. The tentative interplay between Fe3+ and CO in the human CFTR channel.

Fe3+ prevents channel opening by bridging the C-terminal part of the R domain (R2) with intracellular loop 3 (ICL3) and allowing the N-terminal part of the R domain (R1) to block the conductance pathway and to prevent the ATP binding-induced NBD1-NBD2 dimerization. In the non-phosphorylated state, the Fe3+ ligands include C832 and D836 in the R2 domain and H954 in ICL3 while the PKA site S768 (not shown) in the R2 domain H-bonds with H950 from ICL3. Upon phosphorylation of the R domain by PKA, phosphorylated S768 (not shown) and H775 (not shown) in the R2 domain and H950 are also bound to Fe3+ at the R2-ICL3 inteface15–16. Once Fe3+ is removed by CO, the phosphorylated R domain can bind to the ICL1/ICL4 interface via a putative cation-π interaction of the R/K in a PKA site of the R domain with Y161 and F1078 for channel opening by ATP (not shown)31. (A), The closed and open states were prepared with on the cryo-electron microscopy structure of human CFTR and the crystal structures of bacterial transporters Sav1866, respectively22, 24. The individual domains or residues are colored uniquely: cyan, TMD1 and NBD1; light gray,TMD2 and NBD2; red, Lasso motif; blue, unphosphorylatyed R1 and R2 domains; red, phosphorylated R1, R2 or R domain; forest green, Y161 and F1078; magenta, H950 and H954; orange, Fe3+. (B), The closed and open states were based on the cryo-electron microscopy structure of human CFTR and the crystal structure of the peptidase-containing ATP-binding cassette transporter (PCAT) 1 from Clostridium thermocellum, respectively24, 33.

Early studies demonstrated that hemin-induced active chloride secretion in basolaterally depolarized epithelia of colonic tumor cell line Caco-2 is inhibited by NPPB, a nonspecific anion blocker. Because short hemin treatment is without effect on Cl− secretion, it may result from CO, a product of heme degration by heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1)39. Later in 2011, CORM-2, a CO donor, was also found to evoke chloride and HCO3− currents across the apical membrane of rat distal colon, which is blocked by another nonspecific anion blocker glibenclamide14. Given that HO-1 is ubiquitously distributed and apical CFTR is present in rat distal colon40–43, endogenous CO might be a physiological modulator of CFTR channel currents. It is interesting to employ CFTR-specific inhibitor CFTRinh172 to examine whether the CO gas increases CFTR activity by releasing inhibitive Fe3+ from the ICL3-R interface and whether the CO effect is repeated and whether CO enhances Cl− secretion of CF-causing mutants by airway epithelial cells (Figure 1)44. Moreover, because recent studies showed that CO can attenuate Pa biofilm formation and the HO-1/CO pathway plays a multitasking role in activating cytoprotective pathway and CFTR expression in airway epithelial cells45–46, increasing intracellular CO levels could be a promising therapy against lung infection and inflammation in patients with CF.

On the other hand, as the inhibitive Fe3+ site in CFTR has been well defined after the channel is expressed in HEK cells which are cultured in the Fe3+-containing medium, an Fe2+ or Fe3+ site may also be involved in other CO-sensitive ion channels such as Slo1 BKCa when expressed in an Fe2+/Fe3+-containing physiological environment.

Slo1 BKCa channel

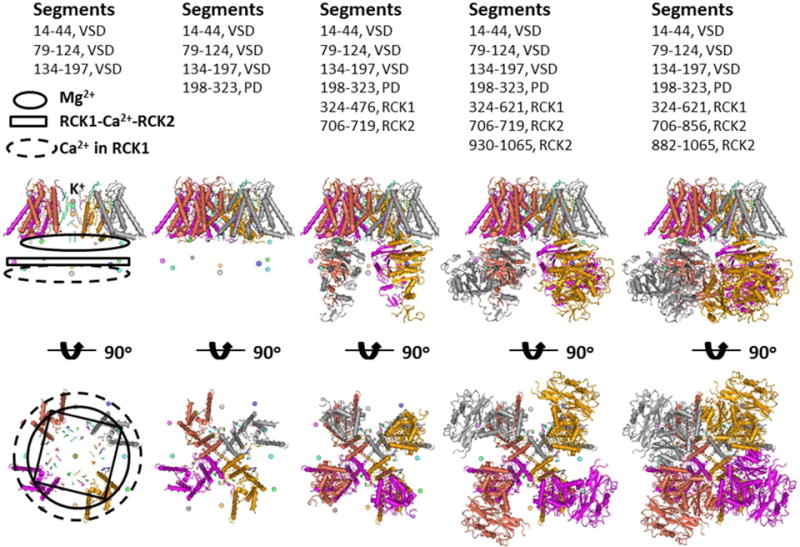

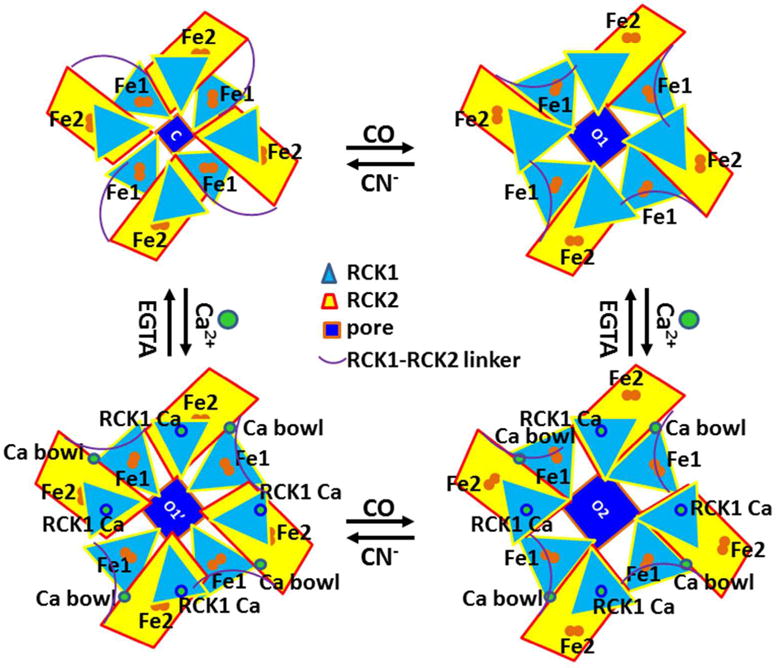

The large-conductance voltage- and calcium-activated human Slo1 BKCa channel is a critical member of the high-conductance Slo family of K+ channel47–49. A coupling of electrical signaling to Ca2+-mediated events allows this channel to regulate muscle contraction, hormone secretion and neuronal excitability50–51. Recent Mg2+/Ca2+-free and Mg2+/Ca2+-bound cryo-EM structures of the full-length Slo1 channel from Aplysia californica demonstrated that the BKCa channel is a tetramer with the transmembrane domain (TMD) on top, the first regulator of K+ conductance (RCK1) domain in the middle and the RCK2 domain at the bottom (Figure 2)52–53. The TMD includes S0 helix, a voltage-sensor domain (VSD) with S1–S4 helices and a pore domain (PD) with S5–S6 helices. Because the VSD of one subunit does not interact with the PD of the other neighboring subunit but the TMD of one subunit interacts with the RCK1 of the other neighboring subunit, the VSD is not domain-swapped with the PD while the TMD is swapped with the RCK1. The homology model of the human Slo1 BKCa channel based on these two structures reveals two Ca2+ -binding sites and an Mg2+ -binding site in the RCK1 and RCK2 domains which form a gating ring. The Ca2+ site consists of D367, R514, G533, E535 and E604 in the RCK1 domain, the Ca2+ bowl site is composed of Q889, D892, D895, D897 from one RCK2 domain and N449 from the other neighboring RCK1 domain, and the Mg2+ site comprises of N172, E339, E374, T396, E399 between the VSD and the RCK1 domain. The Ca2+ bowl has the strongest affinity for Ca2+ while the Mg2+ site has the weakest affinity54. Because R514 in the RCK1 domain forms an ionized H-bond with E902 and a cation-π interaction with Y904 in the RCK2 domain, the two Ca2+ sites may cooperatively interact with each other to activate the Slo1 BKCa channel. In addition, the RCK1 N-lobe, which is shared by both Ca2+ binding sites via N449 or D367, tethers the C terminus of S6 via a polypeptide chain linkage or specifically interfaces with the voltage sensor/S4–S5 linker. Therefore, a rigid body titling of the RCK1 N-lobe may directly or indirectly drive a movement of S6 for channel opening in response to Ca2+ binding to the RCK1 or the RCK2 while the movement of S4 helices in VSD can in turn exert an effect on the gating ring and the apparent Ca2+ binding affinity52–53. Recent electrophysiological measurements also support the notion that the Ca2+-sensitive gating ring facilitates the effective coupling between the VSD and the PD55.

Figure 2. The structural assembly of the Slo1 BKCa channel.

The models were based on the cryo-EM structure of the Slo1 BKCa channel from Aplysia californica53. Four subunits with different colors form a tetramer. The domains with different segments were added from left to right. The voltage sensor domain (VSD) is not swapped with the pore domain (PD) while RCK1 is swapped with TMD (S0+VSD+PD) and RCK2 is swapped with RCK1. The K+ conductance pathway centers in the TMD. From a side view, four Mg2+ form the first metal layer, four Ca2+ at the RC1-RCK2 interface shape the second metal layer and four Ca2+ in RCK1.generate the third metal layer. From a bottom view, the second metal layer has the largest ring while the ring sizes for the first and second metal layers are similar.

The Slo1 BKCa channel has a conserved heme-binding sequence motif 612CXXCH616 in the RCK1-RCK2 linker56. The binding of both heme and hemin to H616, the axial ligand of this human Slo1 channel, increases Po at negative voltages but decreases Po at more positive voltages possibly by disrupting both Ca2+- and voltage-dependent gating via the gating ring57–59. Further studies defined heme-sensitive C612 and C615 as a thiol/disulfide redox switch which controls its affinity for heme and CO and HO-2 and thus tunes channel gating in response to changes in the redox state of the cell under hypoxic and normoxic conditions60. However, Hou and coworkers found that, in the absence of Mg2+ and Ca2+, the channel opening of Slo1 BKCa by CO is inhibited not by the heme-insensitive mutation H616R or C615S/H616R or internal H2O2 or acidification pretreatment but by histidine modifier diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC) or the heme-sensitive mutation H365R or H394R or H365R/H394R or H365A/H394A or D367A in the RCK1 domain. They further observed that the CO sensitivity is prohibited not by Mg2+-insensitive mutation E374A or E399A but by intracellular Ca2+ at the saturating concentration (120 μM)4. Thus, the heme-independent CO stimulation found in the Ca2+-free environment is Ca2+-independent.

On the other hand, Kemp and coworkers reported a different case. Although activation of the Slo1 BKCa channel by CO is partially dependent on [Ca2+]i in the physiological range (0.1–1 μM), in the presence of 2 mM Mg2+ and 300 nM Ca2+ it is not completely prohibited by single or double mutation of H365 and H394 but by 5 mM EGTA or saturating [Ca2+]i (>10 μM) or cyanide or the replacement of the Ca2+ -sensitive S9–S10 module of the C-terminal of hSlo1 with the Ca2+-insensitive S9–S10 module of the C-terminal of mSlo361–62. They also reported that the mutant H365R/H394R in RCK1 domain actually enhances CO sensitivity when [Ca2+]i is in the physiological range. Although CO still potentiates the activity of the heme-bound Slo1 BKCa channel at a higher Ca2+ concentration (10 μM) by binding to heme59–61, CO actually stimulates the hemin-insensitive H616R mutant in the presence of 336 nM Ca2+62. Because of the rapid reversibility of CO and cyanide binding, they proposed that CO activates the Slo1 BKCa channel by binding to a transition metal cluster62. As all these experiments were carried out by using HEK-293 cells which were cultured in the Fe3+-containing medium, and C911G in the RCK2 partially weakens the CO sensitivity62, it is possible that C911 may dynamically bind to an Fe site for channel closure and CO may open the BKCa channel by competing off C911 from the Fe site. Supporting this dynamic binding of C911 to the Fe site, Tang and collaborates found that C911 can be oxidized by H2O2 or MTSEA63. This case is similar to the Zn2+-dependent redox switch at the intracellular dynamic T1-T1 interface of a Kv4.1 channel in which Zn2+ is tightly bound to H104, C131 and C132 in one T1 domain but weakly bound to C110 in the other neighboring T1 domain64. It is interesting that modification of C911 by H2O2 or MTSEA still inhibits the BKCa channel current63. Thus, oxidation C911 by H2O2 or MTSEA may still confer H-bonds to the Fe ligands. More importantly, because the CO effect was still observed in the presence of 11 mM metal chelator EGTA or EDTA and repeated after a washout4, Fe ions may not be released from the high-affinity site by EGTA or EDTA or CN− or CO. In other words, the binding stability constant (logK) of Fe ions for the Slo1 BK1 channel may be more than 35 because logK6 of Fe(II) and Fe(III) for cyanide are 35 and 42, respectively and logK of Fe(II) and Fe(III) for EGTA are 11.8 and 20, respectively65–66. These results are different from those observed in the Kv4.1 channel in which the disulfide bond between C132 and C110 or the H-bond between H104 and oxidized C110 can be formed unless Zn2+ is removed from C131, C132 and H10464. Thus, the putative abnormal heme-independent Fe site in the Slo1 BKCa channel may not be coordinated by canonical protein residues such as cysteine, aspartate or glutamate as found in CFTR but by hydrophobic aromatic residues which may protect Fe ions from releasing by acidification or chelators such as EDTA, EGTA, CO and CN−.

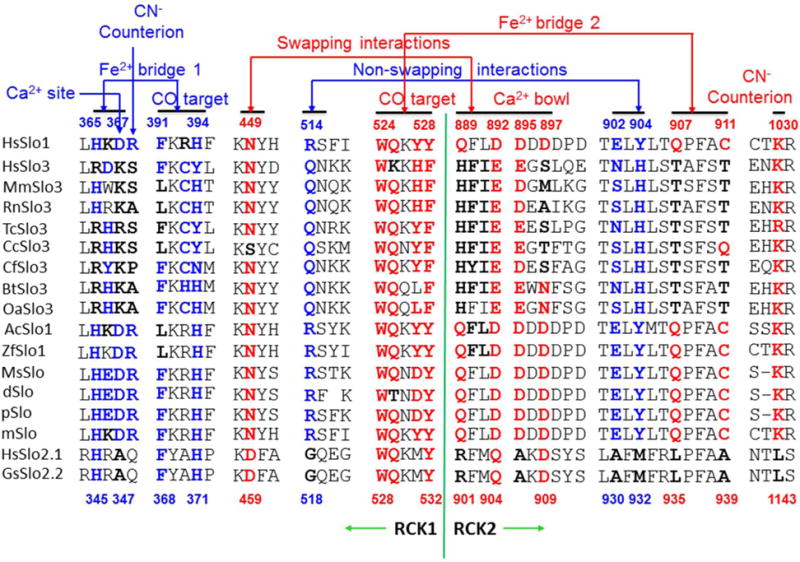

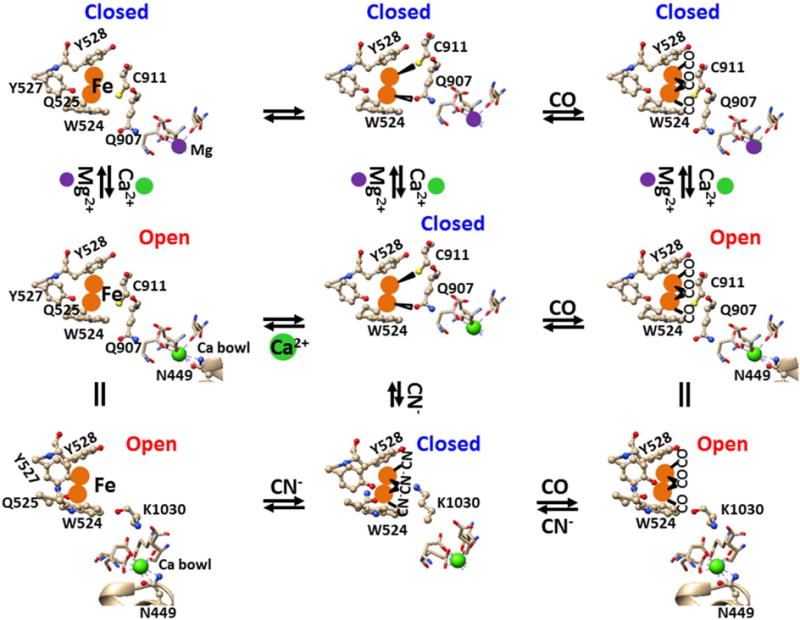

Sequence alignment of Slo BK channels demonstrates a conserved motif 391FXXH/F394 and a highly-conserved motif 524WXXXY/F528 across the species (Figure 3), which may function like water-insoluble cis-cyclopentadienyl iron (II) dicarbonyl dimer to form a binuclear Fe2+ bowl to interact with CO or CN−. Recent structural models of the Slo1 BKCa channels showed that a conserved motif 365HXDR368 is 8 Å distant from the former Fe2+-binding motif and 4.5 Å away from R514/E902/Y904 near the Ca2+ RCK1 site while a conserved motif 907QXXXC911 is 6 Å distant from the latter Fe2+-binding motif and 3.5 Å away from the Ca2+ bowl54–55, 67–68. Thus, two Fe2+ can be sandwiched by F391 and H394 via cation-π interactions to form the first putative binuclear Fe2+ bowl to which H365/D367 or CO or CN− can bind regulating channel gating via the non-swapping interactions of R514 with E902 and Y904 (Figure 4). In the meanwhile, another pair of Fe2+ can be sandwiched by W524 and Y528 via cation-π interactions to produce a second binuclear Fe2+ bowl to which Q907/C911 or CO or CN− can bind modulating channel gating via the swapping interactions of N449 with the Ca2+ bowl (Figure 5).

Figure 3. Sequence alignment of Slo family members.

Residues discussed in the text are bolded and colored. Numbers above and below the sequences refer to the human Slo1 and the chicken Slo2.2, respectively74–75. For the human Slo1 BKCa channel, both the non-swapping interactions of R514 with E902 and Y904 and the swapping interactions of N449 with Q889, D892, D895 and D897 may facilitate a positive RCK1-RCK2 cooperation and channel opening52–53. The former may be coupled to the first putative Fe2+ bridge between H365/D367 and the first putative Fe2+ bowl formed by F391/H394 while the latter may be coupled to the second putative Fe2+ bridge between Q907/C911 and the second putative Fe2+ bowl formed by W524/Y528. CO may target two putative Fe2+ bowls to disrupt two inhibitive Fe2+ bridges while CN− may compete off CO and form a prohibitive salt bridge with counterion R368 or K1030.

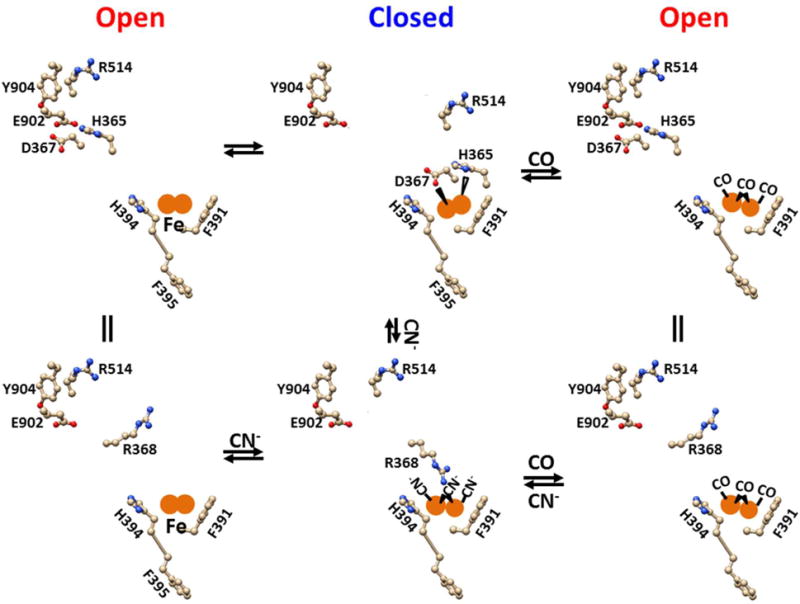

Figure 4. The tentative heme- and Ca2+-independent CO stimulation pathway of the human Slo1 BKCa channel.

The in silico models were based on the crystal structure of the Slo1 BKCa channel from Aplysia californica53. F391 and H394 in the RCK1 may form a high-affinity binuclear Fe2+ bowl via cation-π interactions to prevent a small or large iron chelator to access and to release iron ions. The binding of H365 and D367 to the Fe2+ bowl may disrupt the electrostatic interaction of R514 with E902 and the cation-π interaction of R514 with Y504 and thus promote channel closure. However, CO can compete off H365 and D367 from the Fe2+ bowl and thus reestablish the non-swapping interactions of R514 with E902 and Y904 for channel opening. CN− may compete off CO from the Fe2+ bowl and form an electrostatic attraction with R368 and thus enhance channel closure by disrupting the nonswapping interactions of R514 with E902 and Y904. In any case, the binding of Ca2+ to D367 and R514, G533, E535 and E604 would alleviate the CO or CN− effect by weakening the Fe2+ bridge between H365/D367 and F391/H394.

Figure 5. The tentative heme-independent but Ca2+-dependent CO stimulation pathway of the human Slo1 BKCa channel.

The in silico models were based on the crystal structure of the gating ring of the human Slo1 BKCa channel52. W524, Q525, Y527 and Y528 in the RCK1 may form a high-affinity binuclear Fe2+ bowl to prevent a small or large iron chelator to access and to release iron ions. Two Fe2+ may be sandwiched by W524 and Y528 via cation-π interactions while Q525 may render an additional coordination with two Fe2+ ions to hold the metal in the bowl. Y527 may protect Fe2+ from access of a large chelator. At a lower Ca2+ concentration (<10 μM), the binding of Q907 and C911 in the RCK2 domain to the second Fe2+ bowl in RCK1 domain may disrupt the swapping Ca2+ bridge between N449 and the Ca2+ bowl and thus promote channel closure. CO may bind to Fe2+ to release Q907 and C911 from the second Fe2+ bowl and thus to reestablish the intersubunit Ca2+ bridge for channel opening. CN− may compete off CO from the second Fe2+ bowl and form an electrostatic attraction with K1030 in the RCK2 domain. The resultant disruption of the swapping RCK1-RCK2 Ca2+ bridge may promote channel closure. However, at a higher Ca2+ concentration (>10 μM), Ca2+ bridging N449 with the Ca2+ bowl may pull Q907 and C911 or K1030 away from the second Fe bowl so that no CO or CN− effect would be observed. On the other hand, because Mg2+ is coordinated by 6 oxygen atoms71, the binding of Mg2+ to the Ca2+ bowl may disrupt both the swapping interaction between N449 and the Ca2+ bowl and the non-swapping interactions of R514 with E902/Y904 as a result of the RCK1-RCK2 cooperation52–53, 72. In this case, neither CO nor CN− can regulate channel activity.

In the absence of Ca2+ and Mg2+, N449 and the Ca2+ bowl may be disconnected, the binding of either Q907/C911 or CO or CN− to the second Fe2+ bowl would not alter channel activity. However, the binding of H365/D367 to the first Fe2+ bowl may facilitate channel closure possibly by disrupting the non-swapping interactions of R514 with E902 and Y904. CO may compete off H365/D367 from the first Fe2+ bowl to promote channel opening by rebuilding the non-swapping interactions of R514 with E902 and Y9044. In this case, CN− is expected to reverse the CO stimulation possibly by forming a salt bridge with R368 (Figure 4). The mutation of H365A/R or H394A/R or D367A/R may disrupt the first inhibitive Fe2+ bridge and thus fail to evoke the CO effect4. A mutation of F391A may also be expected to render the channel insensitive to CO in the absence of Ca2+. However, the mutation of Q907A/C911A may not suppress the Ca2+- independent CO stimulation. In addition, acidic activation of the human Slo1 BKCa channel by protonation of H365, D367 or H394 may disrupt the first inhibitive Fe2+ bridge69. Finally, activation of Slo1 BKCa channel by Zn2+ binding to H365/D367/E399 may also result partly from the disconnection of the first inhibitive Fe2+ bridge70.

In the presence of 2 mM Mg2+ and 5 mM EGTA62, the free Mg2+ concentration is about 40 μM (logK of Mg2+ for EGTA is about 566). Because Mg2+ is coordinated with six oxygen atoms71, the binding of Mg2+ to the Ca2+ bowl may leave N449 away from the Ca2+ bowl72. In the meanwhile, the Mg2+-bound Ca2+ bowl may also disrupt the interactions of R514 with E902 and Y904 possibly as a result of a cooperation between two Ca2+ sites52–53. In this case, the release of H365/D367 from the first Fe2+ bowl and the separation of Q907/C911 from the second Fe2+ bowl by CO or CN− would not modulate channel gating (Figure 5)62.

At a low Ca2+concentration (<0.1 μM), the binding of Ca2+ to the Ca2+ bowl may break up both the swapping interaction of N449 with the Ca2+ bowl and the non-swapping interactions of R513 with E902 and Y904 so that the channel is irresponsive to CO or CN−61. In the physiological range of Ca2+ (0.1–1 μM), even if the mutation of H365R/H394R damages the first Fe2+ bridge, CO may still release Q907 and C911 from the second Fe2+ bowl and promote Ca2+ bridging N449 with the Ca2+ bowl for channel opening while CN− may reverse the CO stimulation possibly by forming an inhibitive salt bridge with K1030 and thus disrupting the Ca2+ bridge of N449 with the Ca2+ bowl (Figure 5)62. When C911 is modified by H O 63 2 2 or MTSEA, the introduced adduct may form a putative H-bond with the Fe2+ ligand Y527 or Y528 to prevent the stimulatory Ca2+ bridge between N449 and the Ca2+ bowl. When the RCK2 domain of the human Slo1 channel is replaced with that of mSlo3, this chimeric channel is not activated by Ca2+61. Therefore, even if Ca2+ binds to E880 and E886 at the Ca2+ bowl, N449 is separated from the Ca2+ bowl while R514 may not interact with S893 and H895 possibly as a result of RCK1-RCK2 cooperation52–53. What is more, Q907/C911 have been substituted by T899/T903 in this chimeric channel and thus the second Fe2+ bridge is broken (Figure 3). In this case, even if CO and CN− can compete off H365/D367 from the first Fe2+ bowl, they may not regulate channel gating in either Ca2+ independent or Ca2+-independent manner. At a saturation Ca2+ concentration (>10 μM), the strong binding of Ca2+ to the Ca2+ bowl and the Ca2+ RCK1 site may disconnect both inhibitive Fe2+ bridges and thus the binding of CO or CN− to either Fe2+ bowl would no longer change channel gating4,61. However, CO can still drive channel opening by binding to heme once bound to Slo1 BKCa59.

Miranda and coworkers used patch-clamp fluorometry and observed the 30° rotation of RCK2 against RCK1 with channel activation73, which is not shown in recent structural models of the BK channel52–53, 67–68. Thus, the Ca2+/Mg2+-free Slo1 BK channel may Ca not be fully closed possibly as a result of the absence of two inhibitive Fe2+ bridges53. In the presence of 10 mM Mg2+ or 200 mM Ba2+, the binding of Mg2+ or Ba2+ to the Ca2+ bowl, as required by six coordination oxygen atoms71, may expand the Ca2+ bowl and shrink the RCK1-RCK2 linker but may not disrupt two Fe2+ bridges72. In the presence of 100 μM Cd2+, the possible binding of Cd2+ to H365 and D367 and E399, as Zn2+ does68, may only shrink the RCK1-RCK2 linker and disrupt the first Fe2+ bridge71. However, the binding of Ca2+ to the Ca2+ bowl and the Ca2+ RCK1 site may not only disrupt two Fe2+ bridges but also enhance the swapping interactions of N449 with the Ca2+ bowl and the non-swapping interactions of R514 with E902/Y904 so that the gating ring may be dramatically rearranged (Figure 6)52–53,73. In other words, the Fe2+ bowl may contribute to the large changes in the FRET signal directly or indirectly72–73. In this regard, CO is expected to induce a large conformation change in the gating ring and CN− can reverse it (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The tentative heme-independent gating regulation of the human Slo1 BKCa channel by Ca2+ or CO or CN−.

The in silico models were based on the crystal structures of the gating ring of the human Slo1 BKCa channel52–53. Two intracellular tandem C-terminal RCK1 and RCK2 from each of four channel subunits form a gating ring. Eight pairs of Fe2+ ions may always be bound to the channel. Either the swapping interactions between N449 and the Ca2+ bowl or the non-swapping interactions between R513 and E902/Y904 near the Ca2+ bowl may be required for channel opening52–53. In the absence of Ca2+, the swapping bridges between N449 and the Ca2+ bowl are broken. The Fe2+ bridge between H365/D367 and F391/H394 in RCK1 may also disrupt the non-swapping interactions of R514 with E902 and Y904 so that the channel is fully closed. CO may disrupt this first Fe2+ bridge at the Ca2+ RCK1 site and thus enhance channel opening while CN− can reverse the CO effect. When Ca2+ (<10 μM) is added, the Ca2+ bridge between N449 and the Ca2+ bowl may further promote channel opening because CO has disrupted the second Fe2+ bridge between Q907/C911 and W524/Y528 near the Ca2+ bowl. On the other hand, if Ca2+ (<10 μM) is first applied, the binding of Ca2+ to N449 at the Ca2+ bowl or D367 at the Ca2+ RCK1 site may weaken both Fe2+ bridges for the stimulatory interactions between N449 and the Ca2+ bowl and between R514 and E902/Y904. CO may completely disrupt both Fe2+ bridges so as to promote maximal channel opening. At saturation concentration of Ca2+ (>10 μM), once Ca2+ bridges N449 with the Ca2+ bowl, the binding of Ca2+ to the Ca2+ RCK1 site may drive a gating rotation of RCK1 against RCK2 and TMD. This rotation may expand both RCK1 and RCK2 but shrink the RCK1-RCK2 linker and finally turn TMDs for maximal channel opening73.

Taken together, the first putative Fe2+ bridge may be coupled to the non-swapping interactions of R514 with E902 and Y904 while the second putative Fe2+ bridge may be coupled to the swapping interactions of N449 with the Ca2+ bowl. Although the disruption of the first and second Fe2+ bridges by CO may stimulate channel opening in both Ca2+-independent and Ca2+-dependent manners, respectively, both non-swapping and swapping interactions may facilitate a positive RCK1-RCK2 cooperation (Figure 6). In addition to the stimulatory swapping Mg2+ binding sites at the TMD-RCK1 interface, the stimulatory Ca2+ RCK1 site, the stimulatory swapping Ca2+ bridge at the RCK1-RCK2 interface and the inhibitory heme site at the RCK1-RCK2 linker, two non-swapping inhibitory Fe2+ sites, one at the RCK1-RCK2 interface and the other in the RCK1 domain, are to be identified for full channel closure and a large movement of the gating ring and gating regulation by CO and CN−.

It is also exciting to examine the heme-independent interplay between Fe2+ and CO in other Slo channels. Figure 3 suggests that most of the Slo1 BKCa channels have a potential of the Ca2+-dependent or independent CO stimulation even if the heme site is removed because they have not only two highly-conserved Fe2+ binding motifs but also two kinds of highly-conserved RCK1-RCK2 interactions. Since the hSlo3 BKCa channel is activated by Ca2+ but the mSlo3 BKCa channel is not74, hSlo3 is expected to retain the first Fe2+ binding site and the Ca2+ RCK1 site and the swapping interactions of N438 with N894 and H896 so that the heme- and Ca2+-independent CO stimulation is expected (Figure 3). However, both hSlo3 and mSlo3 BKCa channels may exhibit a heme-dependent CO stimulation because they maintain the heme-binding motif74. For Slo2 channels, although they may have the first Fe2+ bridging motif, the non-swapping RCK1-RCK2 interactions are absent. On the other hand, although they may have a second Fe2+ bowl, no residue bridges with it. What is more, they have not a heme binding motif75. Accordingly, no CO stimulation would be observed.

Conclusions

Heme-independent activation of the CFTR channel and the Slo1 BKCa channel by CO may represent two different modes of gating regulation of ion channels by CO. In the case of CFTR, Fe3+ is bound to the R-ICL3 interface15–16. This interfacial Fe3+ site is formed by traditional coordination ligands such as H950 and H954 from ICL3 and C832 and D836 from the R domain (Figure 1). This Fe3+ binding motif may be 832CXXXDXnHXXXH954. Once Fe3+ is released by CO, a washout cannot reverse the channel activity so that the CO effect would not be repeated. In the case of the human Slo1 BKCa channel, Fe2+ may be always located in a bowl with a putative motif of 524WXXYY/F528 or 391FXXHF395 no matter whether the channel is opened or closed by a change in voltage or Ca2+ or Mg2+ concentrations. However, the dynamic binding of H365/D367 to the first Fe2+ bowl or the dynamic binding of Q907/C911 to the second one may promote channel closure. Thus, CO may compete off H365/D367 and Q907/C911 from the first and second Fe2+ bowls for channel opening in Ca2+- independent and Ca2+-dependent manners, respectively (Figure 4–6). In this case, a washout followed by the CO stimulation can reverse the channel activity and thereby the CO effect can be repeated. Which regulation mode of heme-independent CO action works in ion channels may depend on whether the CO effect can be repeated or not upon a washout. More experiments by using inside-out membrane patches of HEK cells expressing ion channels may further define these two modes and enrich the interplay between iron and CO in ion channels. In the case of heme-dependent CO regulation of ion channels, if heme can be washed out from ion channels such as ENaC76, the potential CO effect on channel activity cannot be repeated. However, if heme cannot be washed out from ion channels such as Slo1 BK57 Ca, the possible CO effect on channel activity may still be repeated once heme is bound. Therefore, the heme-independent regulation of ion channels by CO should be defined without a heme binding site. Given that both apical CFTR and Slo1 BKCa channels in airway epithelial cells play a critical role in airway hydration and volume homeostasis77–79, their CO stimulation may protect CF patients against lung infection and inflammation. Since CO may target other metalloproteins to which transition metals are bound, these two heme-independent regulation modes of CO may have significant and extensive implications for those metalloproteins.

Acknowledgments

The author’s own studies cited in this article were supported by the American Heart Association Grant (10SDG4120011) and National Institute of Health Research Grants R01 NS032337, P01 N037444, T32 AA07463 and 2R56DK056796-10.

Abbreviations

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- CO

carbon monoxide

- CORM

CO-releasing molecule

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- EM

electron microscopy

- ENaC

epithelial Na+ channel

- HO

heme oxygenase

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- HEK

Human embryonic kidney

- DEPC

histidine modifier diethyl pyrocarbonate

- ICL

intracellular loop

- MTSEA

2-aminoethyl methanethiosulfonate hydrobromide

- NPPB

5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzoate

- NPPB-AM

5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzamide

- NBD

nucleotide binding domain

- PCAT

peptidase-containing ATP-binding cassette transporter

- PD

pore domain

- PKA

protein kinase A

- Pa

pseudomonas aeruginosa

- R

regulatory

- RCK

regulator of K+ conductance

- K2p

tandem P domain K+

- TMD

transmembrane domain

- VSD

voltage-sensor domain

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Lim I, Gibbons SJ, Lyford GL, Miller SM, Strege PR, Sarr MG, Chatterjee S, Szurszewski JH, Shah VH, Farrugia G. Carbon monoxide activates human intestinal smooth muscle L-type Ca2+ channels through a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288(1):G7–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00205.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scragg JL, Dallas ML, Wilkinson JA, Varadi G, Peers C. Carbon monoxide inhibits L-type Ca2+ channels via redox modulation of key cysteine residues by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(36):24412–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803037200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dallas ML, Scragg JL, Peers C. Modulation of hTREK-1 by carbon monoxide. Neuroreport. 2008;19(3):345–8. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f51045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hou S, Xu R, Heinemann SH, Hoshi T. The RCK1 high-affinity Ca2+ sensor confers carbon monoxide sensitivity to Slo1 BK channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(10):4039–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800304105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Althaus M, Fronius M, Buchäckert Y, Vadász I, Clauss WG, Seeger W, Motterlini R, Morty RE. Carbon monoxide rapidly impairs alveolar fluid clearance by inhibiting epithelial sodium channels. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41(6):639–50. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0458OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang S, Publicover S, Gu Y. An oxygen-sensitive mechanism in regulation of epithelial sodium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(8):2957–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809100106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkinson WJ, Gadeberg HC, Harrison AW, Allen ND, Riccardi D, Kemp PJ. Carbon monoxide is a rapid modulator of recombinant and native P2X(2) ligand- gated ion channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(3):862–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dallas ML, Boyle JP, Milligan CJ, Sayer R, Kerrigan TL, McKinstry C, Lu P, Mankouri J, Harris M, Scragg JL, Pearson HA, Peers C. Carbon monoxide protects against oxidant-induced apoptosis via inhibition of Kv2.1. FASEB J. 2011;25(5):1519–30. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-173450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dallas ML, Yang Z, Boyle JP, Boycott HE, Scragg JL, Milligan CJ, Elies J, Duke A, Thireau J, Reboul C, Richard S, Bernus O, Steele DS, Peers C. Carbon monoxide induces cardiac arrhythmia via induction of the late Na+ current. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(7):648–56. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0688OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boycott HE, Dallas ML, Elies J, Pettinger L, Boyle JP, Scragg JL, Gamper N, Peers C. Carbon monoxide inhibition of Cav3.2 T-type Ca2+ channels reveals tonic modulation by thioredoxin. FASEB J. 2013;27(8):3395–407. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-227249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkinson WJ, Kemp PJ. Carbon monoxide: an emerging regulator of ion channels. J Physiol. 2011;589(Pt 13):3055–62. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.206706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peers C, Boyle JP, Scragg JL, Dallas ML, Al-Owais MM, Hettiarachichi NT, Elies J, Johnson E, Gamper N, Steele DS. Diverse mechanisms underlying the regulation of ion channels by carbon monoxide. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172(6):1546–56. doi: 10.1111/bph.12760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brazier SP, Telezhkin V, Mears R, Müller CT, Riccardi D, Kemp PJ. Cysteine residues in the C-terminal tail of the human BK(Ca)alpha subunit are important for channel sensitivity to carbon monoxide. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;648:49–56. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2259-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steidle J, Diener M. Effects of carbon monoxide on ion transport across rat distal colon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011:G207–16. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00407.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang G. State-dependent regulation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gating by a high affinity Fe3+ bridge between the regulatory domain and cytoplasmic loop 3. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:40438–40447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.161497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang G. Interplay between inhibitory ferric and stimulatory curcumin regulates phosphorylation-dependent human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator and ΔF508 activity. Biochemistry. 2015;54:1558–1566. doi: 10.1021/bi501318h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreau-Marquis S, Bomberger JM, Anderson GG, Swiatecka-Urban A, Ye S, O’Toole GA, Stanton BA. The DeltaF508-CFTR mutation results in increased biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa by increasing iron availability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L25–37. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00391.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moreau-Marquis S, O’Toole GA, Stanton BA. Tobramycin and FDA-approved iron chelators eliminate Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms on cystic fibrosis cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:305–313. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0299OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreau-Marquis S, Coutermarsh B, Stanton BA. Combination of hypothiocyanite and lactoferrin (ALX-109) enhances the ability of tobramycin and aztreonam to eliminate Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms growing on cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. J Antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2015;70(1):160–6. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talebian L, Coutermarsh B, Channon JY, Stanton BA. Corr4A and VRT325 do not reduce the inflammatory response to P. aeruginosa in human cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Cellular physiology and biochemistry: Internat J Exp Cellul Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;23(1–3):199–204. doi: 10.1159/000204108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hohl M, Briand C, Grutter MG, Seeger MA. Crystal structure of a heterodimeric ABC transporter in its inward-facing conformation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:395–402. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawson RJ, Locher KP. Structure of a bacterial multidrug ABC transporter. Nature. 2006;443:180–185. doi: 10.1038/nature05155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L, Aleksandrov LA, Zhao Z, Birtley JR, Riordan JR, Ford RC. Architecture of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein and structural changes associated with phosphorylation and nucleotide binding. J Struct Biol. 2009;167:242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu F, Zhang Z, Csanády L, Gadsby D, Chen J. Molecular Structure of the human CFTR ion channel. Cell. 2017;169:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mense M, Vergani P, White DM, Altberg G, Nairn AC, Gadsby DC. In vivo phosphorylation of CFTR promotes formation of a nucleotide-binding domain heterodimer. EMBO J. 2006;25:4728–4739. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vergani P, Lockless SW, Nairn AC, Gadsby DC. CFTR channel opening by ATP-driven tight dimerization of its nucleotide-binding domains. Nature. 2005;433:876–880. doi: 10.1038/nature03313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang G. The inhibition mechanism of non-phosphorylated Ser768 in the regulatory domain of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:2171–2182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.145540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang G, Duan DD. Regulation of activation and processing of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) by a complex electrostatic interaction between the regulatory domain and cytoplasmic loop 3. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:40484–40492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.360214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naren AP, Cormet-Boyaka E, Fu J, Villain M, Blalock JE, Quick MW, Kirk KL. CFTR chloride channel regulation by an interdomain interaction. Science. 1999;286(5439):544–8. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang W, Wu J, Bernard K, Li G, Wang G, Bevensee M, Kirk KL. ATP- independent CFTR channel gating and allosteric modulation by phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3888–3893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang G. Molecular basis for Fe(III)-dependent curcumin potentiation of cystic fibrosis transmembraneconductance regulator activity. Biochemistry. 2015;54:2828–2840. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang G, Linsley R, Norimatsu Y. External Zn2+ binding to cysteine-substituted cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator constructs regulates channel gating and curcumin potentiation. FEBS J. 2016;283:2458–75. doi: 10.1111/febs.13752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin DY, Huang S, Chen J. Crystal structures of a polypeptide processing and secretion transporter. Nature. 2015;523(7561):425–30. doi: 10.1038/nature14623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, Burton B, Cao D, Neuberger T, Turnbull A, Singh A, Joubran J, Hazlewood A, Zhou J, McCartney J, Arumugam V, Decker C, Yang J, Young C, Olson ER, Wine JJ, Frizzell RA, Ashlock M, Negulescu P. Rescue of CF airway epithelial cell function in vitro by a CFTR potentiator, VX-770. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(44):18825–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904709106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, Burton B, Stack JH, Straley KS, Decker CJ, Miller M, McCartney J, Olson ER, Wine JJ, Frizzell RA, Ashlock M, Negulescu P. Correction of the F508del-CFTR protein processing defect in vitro by the investigational drug VX-809. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(46):18843–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105787108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cholon DM, Quinney NL, Fulcher ML, Esther CR, Jr, Das J, Dokholyyan NV, Randell SH, Boucher RC, Gentzsch M. Potentiator ivacaftor abrogates pharmacological correction of DeltaF508 CFTR in cystic fibrosis. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:246ra96. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Veit G, Avramescu RG, Perdomo D, Phuan PW, Bagdany M, Apaja PM, Borot F, Szollosi D, Wu YS, Finkneiner WE, Hegedus T, Verkman AS, Lukacs GL. Some gating potentiators, including VX-770, diminish ΔF508-CFTR functional expression. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:246ra97. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stanton BA, Coutermarsh B, Barnaby R, Hogan D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Reduces VX-809 Stimulated F508del-CFTR Chloride Secretion by Airway Epithelial Cells. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0127742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uc A, Husted RF, Giriyappa RL, Britigan BE, Stokes JB. Hemin induces active chloride secretion in Caco-2 cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289(2):G202–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00518.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nanda Kumar NS, Singh SK, Rajendran VM. Mucosal potassium efflux mediated via Kcnn4 channels provides the driving force for electrogenic anion secretion in colon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299(3):G707–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00101.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu D, Zhou J, Wang X, Cui B, An R, Shi H, Yuan J, Hu Z. Traditional Chinese formula, lubricating gut pill, stimulates cAMP-dependent CI− secretion across rat distal colonic mucosa. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010b;134(2):406–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sandle GI, Rajendran VM. Cyclic AMP-induced K+ secretion occurs independently of Cl− secretion in rat distal colon. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303(3):C328–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00099.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xue X, Shi Z, Wang W, Yu X, Feng P, Zhang M, Wang X, Xu J. Huqi San- Evoked Rat Colonic Anion Secretion through Increasing CFTR Expression. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:301640. doi: 10.1155/2015/301640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma T, Thiagarajah JR, Yang H, Sonawane ND, Folli C, Galietta LJV, Verkman ASL. Thiazolidinone CFTR inhibitor identified by high-throughput screening blocks cholera toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1651–1658. doi: 10.1172/JCI16112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murray TS, Okegbe C, Gao Y, Kazmierczak BI, Motterlini R, Dietrich LE, Bruscia EM. The carbon monoxide releasing molecule CORM-2 attenuates Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang PX1, Murray TS, Villella VR, Ferrari E, Esposito S, D’Souza A, Raia V, Maiuri L, Krause DS, Egan ME, Bruscia EM. Reduced caveolin-1 promotes hyperinflammation due to abnormal heme oxygenase-1 localization in lipopolysaccharide-challenged macrophages with dysfunctiona cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J Immunol. 2013;190(10):5196–206. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pallotta BS, Magleby KL, Barrett JN. Single channel recordings of Ca2+-activated K+ currents in rat muscle cell culture. Nature. 1981;293(5832):471–4. doi: 10.1038/293471a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marty A. Ca-dependent K cchannels with large unitary conductance in chromaffin cell mmebranes. Nature. 1981;291:497–500. doi: 10.1038/291497a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Latorre R, Vergara C, Hidalgo C. Reconstitution in planar lipid bilayers of a Ca2+ -dependent K+ channel from transverse tubule membranes isolated from rabbit skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:805–809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.3.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barrett JN, Magleby KL, Pallotta BS. Properties of single calcium-activated potassium channels in cultured rat muscle. J Physiol. 1982;331:211–30. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Contreras GF, Castillo K, Enrique N, Carrasquel-Ursulaez W, Castillo JP, Milesi V, Neely A, Alvarez O, Ferreira G, González C, Latorre R. A BK (Slo1) channel journey from molecule to physiology. Channels (Austin) 2013;7(6):442–58. doi: 10.4161/chan.26242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tao X, Hite RK, MacKinnon R. Cryo-EM structure of the open high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Nature. 2017;541(7635):46–51. doi: 10.1038/nature20608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hite RK, Tao X, MacKinnon R. Structural basis for gating the high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Nature. 2017;541(7635):52–57. doi: 10.1038/nature20775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xia XM, Zeng X, Lingle CJ. Multiple regulatory sites in large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature. 2002;418(6900):880–4. doi: 10.1038/nature00956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang G, Geng Y, Jin Y, Shi J, McFarland K, Magleby KL, Salkoff L, Cui J. Deletion of cytosolic gating ring decreases gate and voltage sensor coupling in BK channels. J Gen Physiol. 2017;149(3):373–387. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201611646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wood LS1, Vogeli G. Mutations and deletions within the S8–S9 interdomain region abolish complementation of N- and C-terminal domains of Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;240(3):623–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang XD1, Xu R, Reynolds MF, Garcia ML, Heinemann SH, Hoshi T. Haem can bind to and inhibit mammalian calcium-dependent Slo1 BK channels. Nature. 2003;425(6957):531–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Horrigan FT, Heinemann SH, Hoshi T. Heme regulates allosteric activation of the Slo1 BK channel. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126(1):7–21. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jaggar JH, Li A, Parfenova H, Liu J, Umstot ES, Dopico AM, Leffler CW. Heme is a carbon monoxide receptor for large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Circ Res. 2005;97:805–12. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000186180.47148.7b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yi L1, Morgan JT, Ragsdale SW. Identification of a thiol/disulfide redox switch in the human BK channel that controls its affinity for heme and CO. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(26):20117–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.116483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Williams SE, Brazier SP, Baban N, Telezhkin V, Müller CT, Riccardi D, Kemp PJ. A structural motif in the C-terminal tail of slo1 confers carbon monoxide sensitivity to human BK Ca channels. Pflugers Arch. 2008;456(3):561–72. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0439-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Telezhkin V, Brazier SP, Mears R, Müller CT, Riccardi D, Kemp PJ. Cysteine residue 911 in C-terminal tail of human BK(Ca)α channel subunit is crucial for its activation by carbon monoxide. Pflugers Arch. 2011;461(6):665–75. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-0924-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tang XD, Garcia ML, Heinemann SH, Hoshi T. Reactive oxygen species impair Slo1 BK channel function by altering cysteine-mediated calcium sensing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11(2):171–8. doi: 10.1038/nsmb725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang G, Strang C, Pfaffinger PJ, Covarrubias M. Zn2+-dependent redox switch in the intracellular T1-T1 interface of a Kv channel. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13637–47. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609182200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dean JA. Lange’s Handbook of Chemistry. 11th. McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1973. pp. 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schatten H, Eisentark A. Salmonella: Methods and Protocals. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2007. p. 297. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu Y, Yang Y, Ye S, Jiang Y. Structure of the gating ring from the human large- conductance Ca2+-gated K+ channel. Nature. 2010a;466(7304):393–7. doi: 10.1038/nature09252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yuan P, Leonetti MD, Pico AR, Hsiung Y, MacKinnon R. Structure of the human BK channel Ca2+-activation apparatus at 3.0 A resolution. Science. 2010;329(5988):182–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1190414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hou S, Xu R, Heinemann SH, Hoshi T. Reciprocal regulation of the Ca2+ and H+ sensitivity in the SLO1 BK channel conferred by the RCK1 domain. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15(4):403–10. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hou S, Vigeland LE, Zhang G, Xu R, Li M, Heinemann SH, Hoshi T. Zn2+ activates large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel via an intracellular domain. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(9):6434–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.069211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bock CW, Kaufman A, Glusker JP. Coordination of water to magnesium cations. Inorg Chem. 1994;33:419–427. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Miranda P, Giraldez T, Giraldez T. Interactions of divalent cations with calcium binding sites of BK channels reveal independent motions within the gating ring. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(49):14055–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611415113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miranda P, Contreras JE, Plested AJ, Sigworth FJ, Holmgren M, Giraldez T. State-dependent FRET reports calcium- and voltage-dependent gating-ring motions in BK channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(13):5217–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219611110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brenker C, Zhou Y, Müller A, Echeverry FA, Trötschel C, Poetsch A, Xia XM, Bönigk W, Lingle CJ, Kaupp UB, Strünker T. The Ca2+-activated K+ current of human sperm is mediated by Slo3. Elife. 2014;3:e01438. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hite RK, Yuan P, Li Z, Hsuing Y, Walz T, MacKinnon R. Cry-Em structure of the Slo2.2 Na+-activated K+ channel. Nature. 2015;527(7577):198–203. doi: 10.1038/nature14958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guo D, Liang S, Wang S, Tang C, Yao B, Wan W, Zhang H, Jiang H, Ahmed A, Zhang Z, Gu Y. Role of epithelial Na+ channels in endothelial function. J Cell Sci. 2016;129(2):290–7. doi: 10.1242/jcs.168831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Manzanares D, Gonzalez C, Ivonnet P, Chen RS, Valencia-Gattas M, Conner GE, Larsson HP, Salathe M. Functional apical large conductance, Ca2+- activated, and voltage-dependent K+ channels are required for maintenance of airway surface liquid volume. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(22):19830–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.185074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Manzanares D, Krick S, Baumlin N, Dennis JS, Tyrrell J, Tarran R, Salathe M. Airway Surface Dehydration by Transforming Growth Factor β (TGF-β) in Cystic Fibrosis Is Due to Decreased Function of a Voltage-dependent Potassium Channel and Can Be Rescued by the Drug Pirfenidone. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(42):25710–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.670885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stanton BA. Adverse Effects of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on CFTR Chloride Secretion and the Host Immune Response. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2017 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00373.2016. 00373.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]