Abstract

We previously reported that the soft coral-derived bioactive substance, sinuleptolide, can inhibit the proliferation of oral cancer cells in association with oxidative stress. The functional role of oxidative stress in the cell-killing effect of sinuleptolide on oral cancer cells was not investigated as yet. To address this question, we introduced the reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenger (N-acetylcysteine [NAC]) in a pretreatment to evaluate the sinuleptolide-induced changes to cell viability, morphology, intracellular ROS, mitochondrial superoxide, apoptosis, and DNA damage of oral cancer cells (Ca9-22). After sinuleptolide treatment, antiproliferation, apoptosis-like morphology, ROS/mitochondrial superoxide generation, annexin V-based apoptosis, and γH2AX-based DNA damage were induced. All these changes were blocked by NAC pretreatment at 4 mM for 1 h. This showed that the cell-killing mechanism of oral cancer cells of sinuleptolide is ROS dependent.

Keywords: soft corals, oral cancer, N-acetylcysteine, oxidative stress, γH2AX

Introduction

Oral cancer is the sixth most prevalent form of cancer worldwide.1,2 Treatment options for oral cancer include surgery and chemotherapy. Several clinically approved drugs such as cisplatin are getting ineffective due to drug resistance in oral cancer therapy.3 Therefore, the discovery of new anti-oral cancer drugs becomes a challenging task.

Marine microbes, flora, and fauna provide promising sources of bioactive natural products, and they are used to develop well-received anticancer drugs.4–6 For example, peptides and roe protein hydrolysates derived from marine fish have been reported to inhibit the proliferation of oral cancer cells.7 The methanolic extract of red alga Gracilaria tenuistipitata was found to inhibit oral cancer cell proliferation.8 Luminacin, a marine microbial extract, was reported to induce autophagy and cell death in head and neck cancer cells.9 Accordingly, marine resources feature abundant natural marine products with potential anticancer effects.

Recently, many soft coral-derived compounds have been reported as having potential applications as anticancer drugs.10,11 Studies have investigated Sinularia lochmodes-derived sinuleptolide for marine natural product identification12 and for use in treating inflammation13 and skin cancer.14 The structure of sinuleptolide was first derived from the soft coral Sinularia sp.15 Alternatively, sinuleptolide was extracted from the soft corals Sinularia leptoclados and S. lochmodes in our laboratory.16,17 However, few studies have investigated the effects of sinuleptolide in the treatment of oral cancer.

In our recent study,18 we reported that oxidative stress was associated with the sinuleptolide-induced killing of oral cancer cells. However, the dependence of oxidative stress in the cell-killing effect of sinuleptolide on oral cancer cells was not investigated. N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a glutathione precursor for replenishing cellular glutathione storage, is a well-known reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenger.19 NAC pretreatment can be used to investigate the role of oxidative stress dependence in drug and natural product-mediated cancer cell death.20–23 Therefore, the purpose of this study is to evaluate the role of oxidative stress in the cell-killing effects of sinuleptolide against oral cancer cells.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures and chemicals

Human oral cancer cells (Ca9-22), purchased from the Health Science Research Resources Bank (HSRRB) (Osaka, Japan), were incubated with DMEM medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and fetal bovine serum.24 Human normal gingival fibroblast cells (HGF-1), purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA), were incubated with DMEM-F12 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA).25 These cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. The structure and preparation of soft corals Sinularia-derived sinuleptolide was isolated from S. lochmodes as described in our previous study.17 It was freshly prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for cell studies. All the DMSO concentrations of sinuleptolide treatments were unified at 0.24%. NAC (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was pretreated with 4 mM for 1 h before sinuleptolide treatment.

Cell viability

CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (MTS) (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) was chosen to measure cell proliferation.24 After plating overnight, Ca9-22 cells were incubated with sinuleptolide for 24 h with or without NAC pretreatment. Finally, the MTS response was measured by an ELISA reader (EZ Read 400 Research Reader; BioChrom, Cambridge, UK).

Intracellular ROS production

Intracellular hydrogen peroxide or other oxidizing ROS can react with 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) and generate fluorescence.26,27 The ROS level can be detected using flow cytometry.8 In brief, after plating overnight, Ca9-22 cells were incubated with sinuleptolide for 3 h with or without NAC pretreatment. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated with 100 nM DCFH-DA in PBS at 37°C for 30 min. After harvesting, cells were resuspended in 1 mL PBS for flow cytometry analysis (BD Accuri™ C6; Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Mean intensity of ROS was collected from 1×104 cell counts.

Mitochondrial superoxide production

The mitochondrial superoxide was reacted with MitoSOX™ Red (Molecular Probes; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA) and generated fluorescence.28 MitoSOX Red was also applied to flow cytometry.18 In brief, after plating overnight, Ca9-22 cells were incubated with sinuleptolide for 1 h with or without NAC pretreatment. Subsequently, cells were incubated with 5 µM MitoSOX 37°C for 30 min. After harvesting, cells were resuspended in 1 mL PBS for flow cytometer analysis (BD Accuri C6). Mean intensity of mitochondrial superoxide was collected from 1×104 cell counts.

DNA damage by γH2AX/propidium iodide

γH2AX is the marker of DNA double-strand breaks, and it can be detected by flow cytometry.24 In brief, sinuleptolide-treated cells were fixed in 70% ethanol. After washing with BSA-T-PBS solution (1% bovine serum albumin and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS; Sigma), cells were incubated with p-Histone H2A.X (Ser 139) monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and BSA-T-PBS buffer in 1:50 dilution at 4°C for 1 h. After washing, Alexa Fluor 488-tagged secondary antibody (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) with BSA-T-PBS buffer in a 1:50 dilution was added for 30 min at room temperature. After the addition of 20 µg/mL of propidium iodide (PI), cells were resuspended for flow cytometry analysis (BD Accuri C6). Mean intensity of γH2AX was collected from 1×104 cell counts.

Statistical analysis

Experimental data were analyzed and expressed as mean ± SD. Data were analyzed using two-sample Student’s t-test with Bonferroni correction. The P-values <0.01 (=0.05/5) are considered as statistically significant.

Results

NAC effect on sinuleptolide-induced cell killing

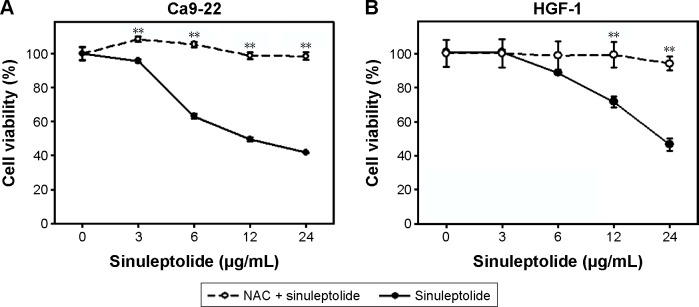

In the MTS assay (Figure 1A and B), sinuleptolide concentration responsively decreased the cell viability (%) of oral cancer cells (Ca9-22) and oral normal cells (HGF-1), but sinuleptolide selectively killed Ca9-22 cells and was less harmful to HGF-1 cells, which was consistent with our previous study.18 The IC50 values of sinuleptolide in Ca9-22 and HGF-1 cells were 11.76 and 22.3 µg/mL, respectively. As NAC is a common ROS scavenger,29,30 this NAC effect was used in the present study to address the dependence of oxidative stress for the sinuleptolide effect on oral cancer compared with normal cells. We found that the sinuleptolide (3–24 µg/mL)-induced cell killing in Ca9-22 and HGF-1 cells was significantly reduced by a pretreatment with NAC (P<0.002) (Figure 1A and B).

Figure 1.

NAC effect on cell viabilities of sinuleptolide-treated oral cancer and normal cells.

Notes: (A) Cell viabilities of oral cancer cells. (B) Cell viabilities of oral normal cells. With or without 4 mM NAC pretreatment for 1 h, oral cancer cells (Ca9-22) or oral normal cells (HGF-1) were incubated with 3, 6, 12, and 24 µg/mL of sinuleptolide for 24 h. Cell viability was measured by the MTS assay. Data, mean ± SD (n=6). **P-value of <0.002 for the significance between data with or without NAC pretreatment.

Abbreviation: NAC, N-acetylcysteine.

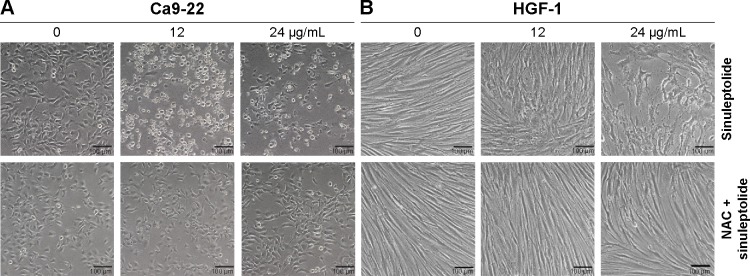

NAC effect on sinuleptolide-induced morphology change

The cell morphology was changed and became more abnormal in sinuleptolide-treated oral cancer cells (Ca9-22) (Figure 2A) than in HGF-1 cells (Figure 2B). At higher concentrations of sinuleptolide (12 and 24 µg/mL), apoptosis-like morphological changes, such as apoptotic bodies and cell shrinkages, were observed in Ca9-22 cells. However, these sinuleptolide-induced apoptosis-like or abnormal morphologies were reduced by NAC pretreatment.

Figure 2.

NAC effect on cell morphology of sinuleptolide-treated oral cancer and oral normal cells.

Notes: NAC pretreatment condition was 4 mM for 1 h. No NAC pretreatment was kept in culture medium for 1 h. Cells were incubated with 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 µg/mL of sinuleptolide for 24 h. (A and B) Cell morphology of sinuleptolide-treated oral cancer cells (Ca9-22) and oral normal cells (HGF-1). Cell morphology was observed under 100× magnification (scale bar is 100 µm).

Abbreviation: NAC, N-acetylcysteine.

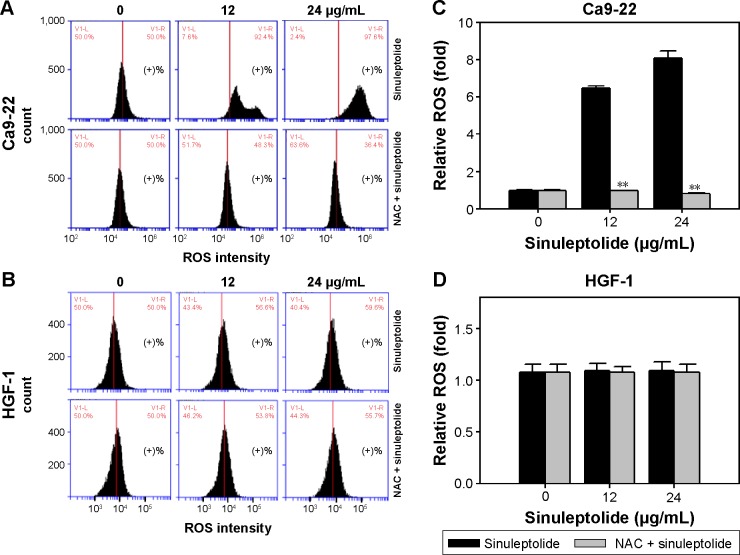

NAC effect on the sinuleptolide-induced ROS generation

Figure 3A and B shows the relative ROS intensity patterns of sinuleptolide-induced ROS generation of Ca9-22 and HGF-1 cells with or without NAC pretreatment. At higher concentrations of sinuleptolide (12 and 24 µg/mL) (Figure 3C), the ROS generation of Ca9-22 cells was upregulated, which was consistent with the results of our previous study.18 After NAC pretreatment, the sinuleptolide-induced ROS generation of Ca9-22 cells was significantly reduced by NAC pretreatment (P<0.002) (Figure 3C). In contrast, the ROS generation of HGF-1 cells was maintained at a basal level with or without NAC pretreatment (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

NAC effect on ROS generation of sinuleptolide-treated oral cancer cells and oral normal cells.

Notes: NAC pretreatment condition was 4 mM for 1 h. No NAC pretreatment was kept in culture medium for 1 h. Oral cancer cells (Ca9-22) were incubated with 0, 12, and 24 µg/mL of sinuleptolide for 6 h. (A and B) Typical ROS patterns of sinuleptolide treated Ca9-22 and HGF-1 cells. The right side of each flow cytometry panel indicates the ROS positive (+%) region. (C and D) Statistics of relative mean intensity of ROS pattern (in A and B). Data, mean ± SD (n=3). **P-value of <0.002 for the significance between data with or without NAC pretreatment.

Abbreviations: NAC, N-acetylcysteine; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

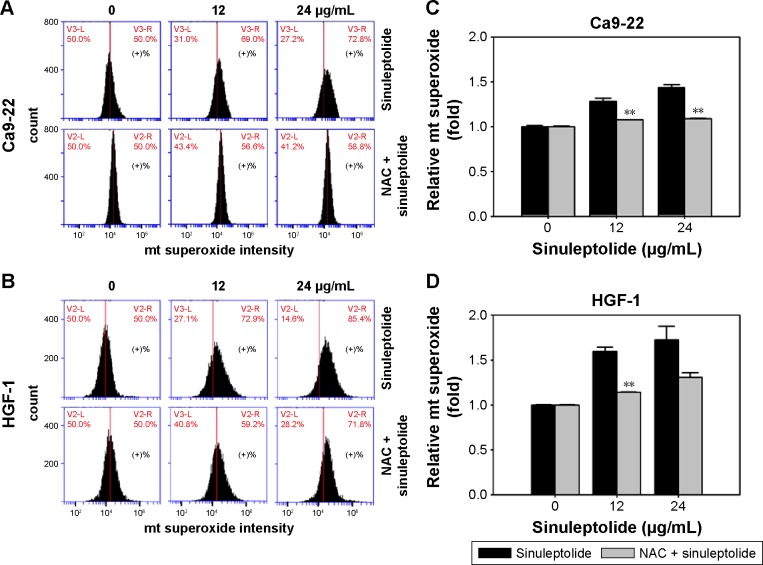

NAC effect on the generation of sinuleptolide-induced mitochondrial superoxide

Mitochondria-specific ROS staining dye (MitoSOX Red) was used to evaluate mitochondrial superoxide by flow cytometry. Figure 4A and B shows the relative mitochondrial superoxide intensity patterns of NAC pretreatment effects against sinuleptolide-treated oral cancer and normal cells. Higher concentrations of sinuleptolide (12 and 24 µg/mL) (Figure 4C and D) induced the mitochondrial superoxide generation of Ca9-22 and HGF-1 cells. NAC pretreatment significantly reduced the sinuleptolide-induced mitochondrial superoxide generation of Ca9-22 and HGF-1 cells (P<0.002).

Figure 4.

NAC effect on mitochondrial (mt) superoxide generation of sinuleptolide-treated oral cancer cells.

Notes: NAC pretreatment condition was 4 mM for 1 h. No NAC pretreatment was kept in culture medium for 1 h. Oral cancer cells (Ca9-22) were incubated with 0, 12, and 24 µg/mL of sinuleptolide for 1 h. (A and B) Typical mt superoxide patterns of sinuleptolide treated Ca9-22 and HGF-1 cells. The right side of each flow cytometry panel indicates the mt superoxide positive (+%) region. (C and D) Statistics of relative mean intensity of mt superoxide pattern (in A and B). Data, mean ± SD (n=3). **P-value of <0.002 for the significance between data with or without NAC pretreatment.

Abbreviation: NAC, N-acetylcysteine.

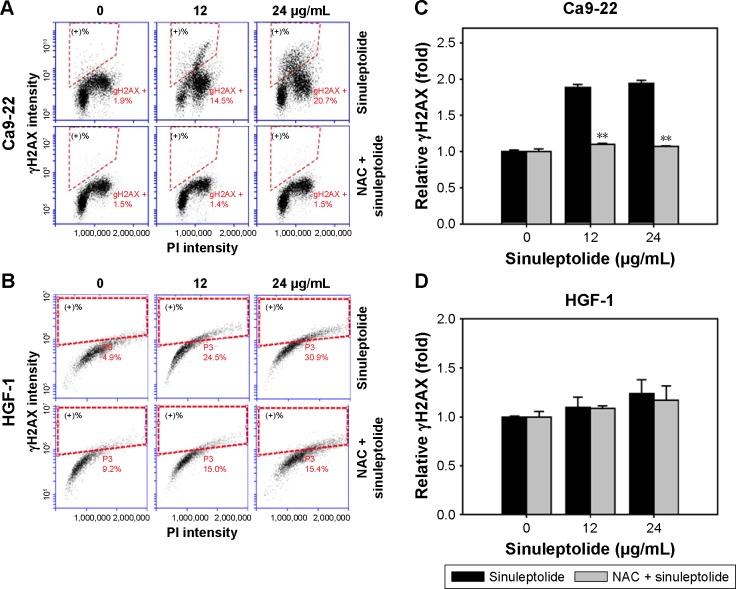

NAC effect on sinuleptolide-induced γH2AX/PI-based DNA damage

Figure 5A and B shows the relative γH2AX intensity patterns of sinuleptolide-induced DNA damage in Ca9-22 and HGF-1 cells with or without NAC pretreatment. The higher concentrations of sinuleptolide (12 and 24 µg/mL) (Figure 5C) dramatically induced the γH2AX expression of Ca9-22 cells, which was consistent with our previous study.18 After NAC pretreatment, the sinuleptolide-induced γH2AX expression in Ca9-22 cells was significantly reduced by NAC pretreatment (P<0.002). In contrast, sinuleptolide-induced γH2AX expression of HGF-1 cells was maintained at a basal level with or without NAC pretreatment (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

NAC effect on γH2AX-based DNA damage in sinuleptolide-treated oral cancer and oral normal cells.

Notes: NAC pretreatment condition was 4 mM for 1 h. No NAC pretreatment was kept in culture medium for 1 h. Oral cancer cells (Ca9-22) were incubated with 0, 6, 12, and 24 µg/mL of sinuleptolide for 24 h. (A and B) Typical γH2AX pattern of sinuleptolide-treated Ca9-22 and HGF-1 cells. Dashed lines of each flow cytometry panel indicate the γH2AX positive (+%) regions. (C and D) Statistics of mean intensity of γH2AX-based DNA damage pattern (in A and B). Data, mean ± SD (n=3). **P-value of <0.002 for the significance between data with or without NAC pretreatment.

Abbreviations: NAC, N-acetylcysteine; PI, propidium iodide.

Discussion

We could show here that NAC pretreatment inhibited sinuleptolide-induced cell killing, apoptosis-like morphology, and apoptosis of oral cancer cells. This indicated the role of oxidative stress in the cytotoxicity provided by sinuleptolide for oral cancer cells. Moreover, oxidative stress is involved in early apoptosis31 and mitochondrial dysfunction.32–34 NAC can interact with ROS, such as hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, superoxide, and hypochlorous acid.35 Consistently, we also found that NAC pretreatment inhibited sinuleptolide-induced ROS and the generation of mitochondrial superoxide. However, NAC is known to show other properties as well. For example, NAC also has anti-inflammatory effects.36–38 Since our study lacks experiments to exclude this possibility, sinuleptolide-induced cytotoxicity of oral cancer cells may also include other than an “ROS-dependent” mechanism.

DCFH-DA is used to detect intracellular ROS such as hydrogen peroxide, but does not specifically detect mitochondrial ROS. In contrast, MitoSOX Red dye has been reported to selectively detect superoxide in the mitochondria of live cells rather than other ROS.39 The role of mitochondrial superoxide was first reported as being involved in sinuleptolide-induced cytotoxicity in the present study. However, sinuleptolide induces cell death in both kinds of cells with different IC50 values (Ca9-22=11.76 and HGF-1=22.3 µg/mL). The reason for some differences only observed with ROS and DNA damage in sinuleptolide-treated cells remains unclear as yet. One possibility is that mitochondrial and cytoplasmic ROS have diverse functions. For example, accumulating evidence suggests that mitochondrial ROS are important for normal cell functioning.40 Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic ROS may play opposing effects throughout the life cycle. For Caenorhabditis elegans, the increase of mitochondrial ROS increases the lifespan of this invertebrate, whereas the increase of cytoplasm ROS decreases its lifespan.41 However, the detailed function of mitochondrial and cytoplasmic ROS in sinuleptolide-induced cytotoxicity against cancer cells warrants further investigation.

p53 is reported to highly regulate redox homeostasis and to modulate several ROS-regulating genes.42 In contrast, ROS can modify p53 conformation to adjust the transcription of p53.42 In the current study, ROS was validated to play an important role in sinuleptolide-induced cell death of oral cancer cells. However, the role of p53 in sinuleptolide-treated cells was not investigated in the current study. Furthermore, the status of p53 in Ca9-22 cells is a mutant form,43,44 but it is wild-type (wt) in the HGF-1 cells. Cells with mutant or wt p53 may display different responses. For example, hyperthermia induced apoptosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells (wt p53) and decreased IL-12 expression, but it increased IL-12Rβ1 in OSCC (mutated p53).45 Accordingly, the role of p53 in sinuleptolide-induced antiproliferation and DNA damage effects of oral cancer cells warrants further investigation in the future.

Mitochondria are commonly assumed to have a tubular form in healthy cells, but donut or blob forms increased with mitochondrial superoxide,46 suggesting that mitochondrial shape may change at different conditions of mitochondrial ROS generation. The mitochondrial superoxide intensity increased upon oxidative stress with inhibitors of the mitochondrial complex I (rotenone) and mitochondrial complex II (antimycin).46 NAC pretreatment has been reported to reduce mitochondrial superoxide levels and mitochondrial donut or blob formations.46 This suggests further investigation of sinuleptolide-induced mitochondrial shape change.

Moreover, oxidative stress commonly induces DNA damage,47 but we found that sinuleptolide-induced DNA damage was reduced by NAC pretreatment, suggesting that oxidative stress plays an important role in the DNA damaging effect of sinuleptolide in oral cancer cells. In addition, the sinuleptolide-induced DNA damage effect may have led to apoptosis in our previous study.18 Our preliminary result also found that sinuleptolide-induced apoptosis may be reduced by NAC pretreatment as indicated by the cleaved Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) assay (data not shown).

Some oxidative stress modulating drugs have been reported to modulate the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress provided by oxidative stress.48,49 ROS has also been reported to induce autophagy when exposed to nonmarine drugs and marine drugs.50 Because sinuleptolide-induced killing of oral cancer cells was shown to depend on oxidative stress, the possible responses of ER stress and autophagy in sinuleptolide-treated oral cancer cells warrant further investigation. Moreover, NAC was reported to inactivate c-Jun N-terminal kinase, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, activating protein-1, and nuclear factor kappa B.51 These kinase signaling proteins need to be further investigated in terms of the sinuleptolide mediation in the future.

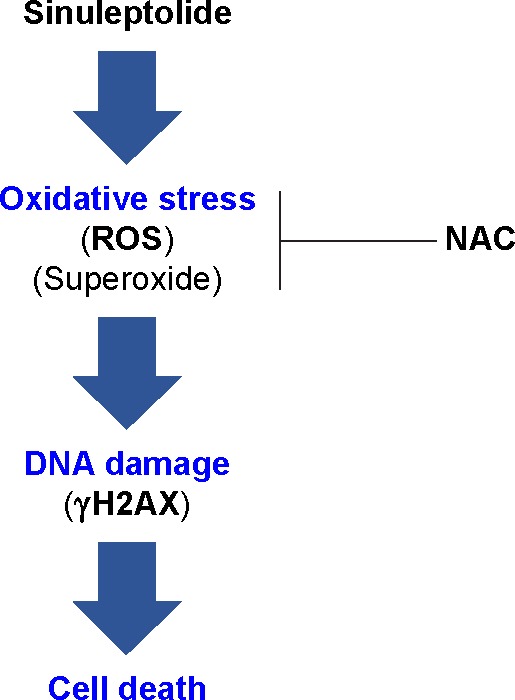

Conclusion

In conclusion, we demonstrated that sinuleptolide induces cell killing, apoptosis, and DNA damage in oral cancer cells by allowing for relatively high cellular ROS levels. This effect was significantly reduced by NAC pretreatment that allows ROS scavengers to reduce the actual ROS content (Figure 6). This suggests that the marine bioactive compound sinuleptolide kills oral cancer cells by mediating oxidative stress.

Figure 6.

Overview of the hypothesized mechanism of sinuleptolide-induced killing of human oral cancer cells (Ca9-22) involving oxidative stress.

Notes: The role of oxidative stress was demonstrated by pretreatment with NAC that scavenges ROS and prevents mitochondrial superoxide generation. NAC consequently inhibits DNA damage and cell death.

Abbreviations: NAC, N-acetylcysteine; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds of the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 104-2320-B-037-013-MY3, MOST 104-2320-B-110-001-MY2, and MOST 105-2314-B-037-036), the National Sun Yat-sen University-KMU Joint Research Project (#NSYSU-KMU 106-p001), the Kaohsiung Municipal Ta-Tung Hospital (KMUH105-5R61), and the Health and welfare surcharge of tobacco products, the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan, Republic of China (MOHW105-TDU-B-212-134007). The authors thank Dr Hans-Uwe Dahms for help with English editing.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(4–5):309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen PE. Oral cancer prevention and control – the approach of the World Health Organization. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(4–5):454–460. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hager S, Ackermann CJ, Joerger M, Gillessen S, Omlin A. Anti-tumour activity of platinum compounds in advanced prostate cancer-a systematic literature review. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(6):975–984. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sithranga Boopathy N, Kathiresan K. Anticancer drugs from marine flora: an overview. J Oncol. 2010;2010:214186. doi: 10.1155/2010/214186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JC, Hou MF, Huang HW, et al. Marine algal natural products with anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer properties. Cancer Cell Int. 2013;13(1):55. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-13-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JK, Kang KA, Piao MJ, et al. Generation of reactive oxygen species and endoplasmic reticulum stress by Dictyopteris undulata extract leads to apoptosis in human melanoma cells. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2015;34(3):191–200. doi: 10.1615/jenvironpatholtoxicoloncol.2015013074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han Y, Cui Z, Li YH, Hsu WH, Lee BH. In vitro and in vivo anticancer activity of pardaxin against proliferation and growth of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Mar Drugs. 2016;14(1):2. doi: 10.3390/md14010002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeh CC, Yang JI, Lee JC, et al. Anti-proliferative effect of methanolic extract of Gracilaria tenuistipitata on oral cancer cells involves apop-tosis, DNA damage, and oxidative stress. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12(1):142. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin YS, Cha HY, Lee BS, et al. Anti-cancer effect of luminacin, a marine microbial extract, in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma progression via autophagic cell death. Cancer Res Treat. 2016;48(2):738–752. doi: 10.4143/crt.2015.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yen WH, Hu LC, Su JH, et al. Norcembranoidal diterpenes from a For-mosan soft coral Sinularia sp. Molecules. 2012;17(12):14058–14066. doi: 10.3390/molecules171214058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin YY, Lin SC, Feng CW, et al. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of the marine-derived compound excavatolide B isolated from the culture-type Formosan Gorgonian Briareum excavatum. Mar Drugs. 2015;13(5):2559–2579. doi: 10.3390/md13052559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.el Sayed KA, Hamann MT. A new norcembranoid dimer from the red sea soft coral Sinularia gardineri. J Nat Prod. 1996;59(7):687–689. doi: 10.1021/np960207z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takaki H, Koganemaru R, Iwakawa Y, Higuchi R, Miyamoto T. Inhibitory effect of norditerpenes on LPS-induced TNF-alpha production from the Okinawan soft coral, Sinularia sp. Biol Pharm Bull. 2003;26(3):380–382. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang CH, Wang GH, Chou TH, et al. 5-epi-Sinuleptolide induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis through tumor necrosis factor/mitochondria-mediated caspase signaling pathway in human skin cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820(7):1149–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shoji N, Umeyama A, Arihara S. A novel norditerpenoid from the Okinawan soft coral Sinularia sp. J Nat Prod. 1993;56(9):1651–1653. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed AF, Shiue RT, Wang GH, Dai CF, Kuo YH, Sheu JH. Five novel norcembranoids from Sinularia leptoclados and S. parva. Tetrahedron. 2003;59(8):7337–7344. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tseng YJ, Ahmed AF, Dai CF, Chiang MY, Sheu JH. Sinulochmodins A-C, three novel terpenoids from the soft coral Sinularia lochmodes. Org Lett. 2005;7(17):3813–3816. doi: 10.1021/ol051513j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang YT, Huang CY, Li KT, et al. Sinuleptolide inhibits proliferation of oral cancer Ca9–22 cells involving apoptosis, oxidative stress, and DNA damage. Arch Oral Biol. 2016;66:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson KR, Neilson IL, Barrett F, et al. Evaluation of the antioxidant properties of N-acetylcysteine in human platelets: prerequisite for bioconversion to glutathione for antioxidant and antiplatelet activity. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2009;54(4):319–326. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181b6e77b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang HS, Tang JY, Yen CY, et al. Antiproliferation of Cryptocarya concinna-derived cryptocaryone against oral cancer cells involving apoptosis, oxidative stress, and DNA damage. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16(1):94. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1073-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen CY, Yen CY, Wang HR, et al. Tenuifolide B from Cinnamomum tenuifolium stem selectively inhibits proliferation of oral cancer cells via apoptosis, ROS generation, mitochondrial depolarization, and DNA damage. Toxins (Basel) 2016;8(11):319. doi: 10.3390/toxins8110319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shu CW, Chang HT, Wu CS, et al. RelA-mediated BECN1 expression is required for reactive oxygen species-induced autophagy in oral cancer cells exposed to low-power laser irradiation. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0160586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu CH, Bai LY, Tsai MH, et al. Pharmacological exploitation of the phenothiazine antipsychotics to develop novel antitumor agents-A drug repurposing strategy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27540. doi: 10.1038/srep27540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiu CC, Haung JW, Chang FR, et al. Golden berry-derived 4beta-hydroxywithanolide E for selectively killing oral cancer cells by generating ROS, DNA damage, and apoptotic pathways. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e64739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yen YH, Farooqi AA, Li KT, et al. Methanolic extracts of Solieria robusta inhibits proliferation of oral cancer Ca9–22 cells via apoptosis and oxidative stress. Molecules. 2014;19(11):18721–18732. doi: 10.3390/molecules191118721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan WH, Wu HJ, Hsuuw YD. Curcumin inhibits ROS formation and apoptosis in methylglyoxal-treated human hepatoma G2 cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1042:372–378. doi: 10.1196/annals.1338.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carter WO, Narayanan PK, Robinson JP. Intracellular hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion detection in endothelial cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;55(2):253–258. doi: 10.1002/jlb.55.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukhopadhyay P, Rajesh M, Yoshihiro K, Hasko G, Pacher P. Simple quantitative detection of mitochondrial superoxide production in live cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358(1):203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hseu YC, Lee MS, Wu CR, et al. The chalcone flavokawain B induces G2/M cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in human oral carcinoma HSC-3 cells through the intracellular ROS generation and downregulation of the Akt/p38 MAPK signaling pathway. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60(9):2385–2397. doi: 10.1021/jf205053r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shih HC, El-Shazly M, Juan YS, et al. Cracking the cytotoxicity code: apoptotic induction of 10-acetylirciformonin B is mediated through ROS generation and mitochondrial dysfunction. Mar Drugs. 2014;12(5):3072–3090. doi: 10.3390/md12053072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samhan-Arias AK, Martin-Romero FJ, Gutierrez-Merino C. Kaempferol blocks oxidative stress in cerebellar granule cells and reveals a key role for reactive oxygen species production at the plasma membrane in the commitment to apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37(1):48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh SH, Lim SC. A rapid and transient ROS generation by cadmium triggers apoptosis via caspase-dependent pathway in HepG2 cells and this is inhibited through N-acetylcysteine-mediated catalase upregulation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;212(3):212–223. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li JJ, Tang Q, Li Y, et al. Role of oxidative stress in the apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma induced by combination of arsenic trioxide and ascorbic acid. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27(8):1078–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ehlers RA, Hernandez A, Bloemendal LS, Ethridge RT, Farrow B, Evers BM. Mitochondrial DNA damage and altered membrane potential (delta psi) in pancreatic acinar cells induced by reactive oxygen species. Surgery. 1999;126(2):148–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aruoma OI, Halliwell B, Hoey BM, Butler J. The antioxidant action of N-acetylcysteine: its reaction with hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, superoxide, and hypochlorous acid. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;6(6):593–597. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atalay F, Odabasoglu F, Halici M, et al. N-acetyl cysteine has both gastro-protective and anti-inflammatory effects in experimental rat models: its gastro-protective effect is related to its in vivo and in vitro antioxidant properties. J Cell Biochem. 2016;117(2):308–319. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lasram MM, Lamine AJ, Dhouib IB, et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of N-acetylcysteine against malathion-induced liver damages and immunotoxicity in rats. Life Sci. 2014;107(1–2):50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sadowska AM, Manuel YKB, De Backer WA. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory efficacy of NAC in the treatment of COPD: discordant in vitro and in vivo dose-effects: a review. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2007;20(1):9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mukhopadhyay P, Rajesh M, Hasko G, Hawkins BJ, Madesh M, Pacher P. Simultaneous detection of apoptosis and mitochondrial superoxide production in live cells by flow cytometry and confocal microscopy. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(9):2295–2301. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sena LA, Chandel NS. Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell. 2012;48(2):158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaar CE, Dues DJ, Spielbauer KK, et al. Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic ROS have opposing effects on lifespan. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(2):e1004972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He Z, Simon HU. A novel link between p53 and ROS. Cell Cycle. 2013;12(2):201–202. doi: 10.4161/cc.23418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Imai Y, Ohnishi K, Yasumoto J, et al. Glycerol enhances radiosensitivity in a human oral squamous cell carcinoma cell line (Ca9–22) bearing a mutant p53 gene via Bax-mediated induction of apoptosis. Oral Oncol. 2005;41(6):631–636. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaneda Y, Shimamoto H, Matsumura K, et al. Role of caspase 8 as a determinant in chemosensitivity of p53-mutated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. J Med Dent Sci. 2006;53(1):57–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yasumoto J, Kirita T, Takahashi A, et al. Apoptosis-related gene expression after hyperthermia in human tongue squamous cell carcinoma cells harboring wild-type or mutated-type p53. Cancer Lett. 2004;204(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmad T, Aggarwal K, Pattnaik B, et al. Computational classification of mitochondrial shapes reflects stress and redox state. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e461. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Orrenius S. Mechanisms of Oxidative Cell Damage. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhäuser Verlag; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farooqi AA, Li KT, Fayyaz S, et al. Anticancer drugs for the modulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(8):5743–5752. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3797-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim JK, Kang KA, Ryu YS, et al. Induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress via reactive oxygen species mediated by luteolin in melanoma cells. Anticancer Res. 2016;36(5):2281–2289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farooqi AA, Fayyaz S, Hou MF, Li KT, Tang JY, Chang HW. Reactive oxygen species and autophagy modulation in non-marine drugs and marine drugs. Mar Drugs. 2014;12(11):5408–5424. doi: 10.3390/md12115408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zafarullah M, Li WQ, Sylvester J, Ahmad M. Molecular mechanisms of N-acetylcysteine actions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60(1):6–20. doi: 10.1007/s000180300001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]