Review on MDSC biology and how it may be applied to clinical graft-versus-host disease.

Keywords: GVHD, MDSC, cellular therapy, inflammation, immune suppression

Abstract

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) can be a devastating complication for as many as a third of patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCT). A role for myeloid cells in the amplification of GVHD has been demonstrated; however, less is understood about a potential regulatory role that myeloid cells play or whether such cells may be manipulated and applied therapeutically. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a naturally occurring immune regulatory population that are engaged and expand shortly after many forms of immune distress, including cancer, trauma, and infection. As MDSCs are often associated with chronic disease, inflammation, and even the promotion of tumor growth (regarding angiogenesis/metastasis), they can appear to be predictors of poor outcomes and therefore, vilified; yet, this association doesn’t match with their perceived function of suppressing inflammation. Here, we explore the role of MDSC in GVHD in an attempt to investigate potential synergies that may be promoted, leading to better patient outcomes after allo-HCT.

Introduction

Myeloid-derived cells play a critical role in the initiation and amplification of immune responses. Exquisitely sensitive to changes in their microenvironment, myeloid cells form the first line of defense in the innate immune system and subsequently shape the adaptive immune response. In addition, myeloid cells have the capacity to reshape and dampen ongoing responses dynamically, limiting immune pathology and thereby, protecting the host from devastating inflammatory injury.

MDSCs are broadly described as a diverse collection of immature myeloid-lineage cells with regulatory or suppressive properties [1, 2]. Derived from the BM, MDSCs were originally described as abnormal/null myeloid lineage cells with leukocyte inhibitory capacity [3, 4]. Consistent with a diversity of cancer types, associated MDSCs demonstrate a high degree of heterogeneity, owing to a unique microenvironment and tumor-derived factors [5]. MDSCs expand and associate with tumors, promoting escape from T cell immunity, and are being targeted clinically to promote tumor regression [6, 7]. Recent consensus has defined a few types of MDSCs that can be distinguished by cytology/morphology, as well as the differential expression of cell-surface antigens. In mice, the glycoproteins Ly6G and Ly6C define granulocytic (or PMN) PMN-MDSCs that are CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6Clo and M-MDSCs that are CD11b+Ly6GloLy6Chi [8]. In humans, PMN-MDSCs are CD14−CD11b+, CD15+, or CD66b+, and M-MDSCs are CD14+CD11b+HLA-DRlo/CD15−. A third subpopulation described in humans is the early MDSCs, which are lineage-negative (CD3/14/15/19/56/HLA-DR) CD33+. Critically, MDSCs must also demonstrate functional suppression. In mice, splenic PMN-MDSCs, containing high amounts of reactive oxygen species, were found to require cell–cell contact with activated antigen-specific T cells, whereas M-MDSCs expressing NO and ARG1 had increased potency and suppressed nonspecifically [9]. Antigen specificity has been difficult to demonstrate in humans; however, it has been proposed that MDSCs are licensed by tumors, acting locally to suppress activated T cells [9]. A variety of associated biochemical and molecular parameters include regulation of transcription factors associated with inflammatory and stress-response reactions, as well as cytokines and cell-surface antigens that facilitate anti-inflammatory responses [8]. Common suppressor mechanisms that operate in the context of transplantation responses include inducible NO and iNOS, HO-1, NOX2, IFN-γ, TGF-β, and depletion of essential amino acids, such as l-arginine and cysteine [10], as well as promotion of Tregs.

Whereas the regulatory role for myeloid cells can impede immune therapy efforts against cancer, these immune-suppressive properties may be beneficial as therapy for autoimmunity and allo-HCT. In this review, we will examine the potential therapeutic role of MDSCs in allo-HCT, with a particular emphasis on GVHD and GVL effects.

CORRELATION BETWEEN DONOR GRAFT-DERIVED AND POSTALLO-HCT REPOPULATING MDSCs AND OUTCOME

For >2 decades, mouse and human studies have shown that G-CSF has a wide range of anti-inflammatory immune effects. These include decreased inflammatory cytokines [11], increased production of IL-10 [12], mobilization of Th2-inducing DCs [13], Th2 and NKT cell polarization, and reduced NK cell numbers and function [14–18], which in aggregate, point to a reduction in acute GVHD capacity by donor grafts. Early murine studies with CpG and IFA treatment of donor mice demonstrated increased peripheral blood and splenic CD11b+Gr-1+ cells that efficiently suppressed alloreactivity in vitro and GVHD in vivo [19]. In other murine studies, immature myeloid cells (CD11b+Gr1+) in G-CSF-treated donors were found to suppress acute GVHD via an IDO enzyme-mediated tryptophan catabolism [20]. In a related study examining a synthetic fusion of G-CSF and Flt-3 ligand (progenipoietin-1), MacDonald et al. [21] have shown GVHD suppression via expansion of regulatory myeloid APCs, which in turn, promote class II-dependent, IL-10-producing T cells. In other studies, G-CSF pretreatment was shown to prevent GVHD with retention of GVL responses by suppressor IL-10+ neutrophils through the generation of Tregs [22]. In patients, G-CSF-mobilized PBSCs resulted in hyporesponsive mononuclear cells, with variable effects in CD4+ T cells, and a 50-fold increase in suppressor CD14+ monocytes that contributed to the overall hyporesponsiveness of PBSCs [23]. Despite the shift toward immune-regulatory populations, neither a randomized trial of 172 HLA identical-related G-CSF PBSCs compared with BM grafts [24] nor a retrospective analysis of 331 PBSC and 586 BM recipients [25] showed a significant reduction in acute or chronic GVHD. A reconciliation of these observations could be related to the frequency, type, and potency of donor MDSCs in G-CSF PBSCs. Toward that end, studies have shown that PMN-MDSCs and M-MDSCs are increased in the blood during G-CSF stem-cell mobilization in human donors (Fig. 1A) [26]. An analysis of 60 patients who received unrelated donor G-CSF PBSCs has shown that graft M-MDSC cell content was predictive of acute GVHD risk [27]. Likewise, in an analysis of 62 patients receiving haploidentical G-CSF PBSCs, higher absolute numbers of M-MDSCs and to a significant but lesser extent, PMN-MDSCs correlated with reduced acute GVHD [28].

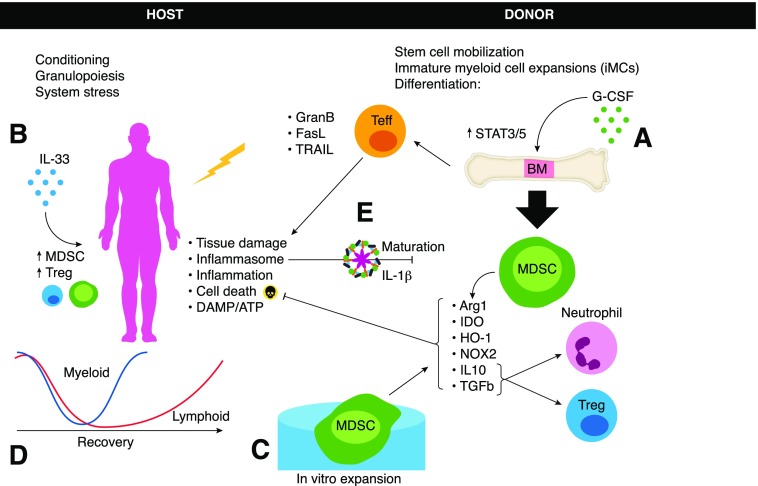

Figure 1. G-CSF has been used to (A) promote stem cell mobilization but also to promote anti-inflammatory effects, including the expansion of MDSCs that can be beneficial for the host in ameliorating GVHD via a variety of suppressive functions.

Alternatively, cytokine priming of the host promoted through IL-33 (B) has been shown to support endogenous regulatory cells also capable of limiting GVHD pathology. Additional options for MDSC-associated therapeutic benefits include in vitro expansion (C) of MDSC that can be tailored for desired subsets or mechanism of action as needed. After conditioning, myeloid cell recovery is known to outpace lymphoid recovery (D); however, suppressive phenotype myeloid cells are likely unable to overcome host-derived APC activation in the early stages, which play a role in GVHD amplification. Finally, conditioning regimens also result in cell death and release of danger signals, including inflammasome-activating signals (E) that promote increased inflammation and act directly on MDSCs to subvert function. Teff, Effector T cell; GranB, Granzyme B; TRAIL, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand; DAMP, damage-associated molecular pattern.

The implication from these studies is that rapid and substantial MDSC repopulation postallo-HCT contributes to acute GVHD amelioration and tolerance induction. In murine recipients of T cell-depleted grafts, delaying donor lymphocyte infusion by 3 wk provided effective GVL control while limiting GVHD. It was shown that CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6C+ myeloid cells expanded during this time, peaking at wk 3 with expression of IFN-γ and NO associated with suppression of alloresponses in vitro [29]. With the use of a tolerogenic protocol based on total lymphoid irradiation (multiple low doses with an in vivo T cell-depleting anti-thymocyte globulin/serum), Strober and colleagues [30] have shown that acute GVHD is markedly inhibited in mice and humans. Mechanistically, this protocol led to an increase in NKT cells [31–33], Tregs [34–36], and ARG1+, IL-4Rα+programmed death-ligand 1+ MDSCs that independently have been shown to have GVHD suppressor capacities [37]. In rodent studies, suppression of GVHD was dependent on MDSCs, as depletion abrogated tolerance, and add back restored tolerance; NKT cell production of IL-4 supported MDSC activation [30]. Moreover, the GVHD-protective effect of adoptively transferred donor NKT cells was dependent on Treg expansion, which itself required MDSCs [33].

Murine MDSCs can also be induced by cytokine pretreatment of the recipient. For example, in vivo administration of exogenous IL-33 has been shown to induce MDSCs and Tregs, resulting in reduced murine cardiac allograft rejection [38]. Pretreatment of recipients with IL-33, beginning before murine allo-HCT, increased MDSCs and Tregs, suppressing GVHD lethality (Fig. 1B) [39]. Conversely, IL-33, a member of the IL-1/IL-1R family, can function as an alarmin and in the presence of proinflammatory cytokines released during the GVHD response, accelerating lethality [40, 41]. Blockade of IL-33/IL-33R binding reduces GVHD, while increasing MDSCs that inhibits immunogenic gut CD103+ DCs [41].

After many forms of allo-HCT conditioning, lymphocytes that make up the adaptive immune system take months to recover fully, whereas myeloid subsets begin repopulation within days. Many of the factors known to promote MDSC expansion, including G-CSF, GM-CSF, and IL-6, are present during the first month post-BMT, suggesting that MDSC expansion could be anticipated, although proinflammatory factors are also present, and we have yet to grasp fully the interplay and outcomes that result in tipping the balance toward recovery versus pathology. It should also be noted that many commonly used forms of conditioning promote antigen presentation and activation of APCs, which in turn, contribute to GVHD system wide, putting regulatory networks at a temporal disadvantage. In a murine study, MDSC accumulation post-BMT correlated with the number of T cells input and the resulting GVHD pathology. Whereas endogenous MDSCs early post-transplant were evident and accumulated even under syngeneic transplant conditions, as a result of radiation-induced injury, the magnitude and maintenance of the MDSC response were dictated by allogeneic T cell dose and the severity of GVHD [42]. In patients, a recent study analyzing M-MDSC and PMN-MDSC subsets, at 6 time points in the first 3 mo, found that after allo-HCT, MDSC subsets recovered within 2–4 wk, which was positively correlated with B and T cell numbers [43]. Of note, a greater increase in the granulocytic MDSC ratio relative to pretransplant levels was an indicator of lower GVHD scores at 1 mo, suggesting that when MDSCs expand to a greater degree during the post-BMT phase of recovery, they are associated with better outcomes. Furthermore, MDSCs were functional in suppressing third-party CD4+ T cell proliferation and Th1 differentiation while promoting Treg development. In a retrospective study of 51 postallo-HCT patients, the frequency of peripheral blood CD14+HLA-DRlow/neg myeloid cells was significantly increased in acute GVHD patients and shown to be associated with T cell dysfunction [44]. Serum G-CSF and IL-6 levels correlated positively with CD14+HLA-DRlow/neg cells, and compared with healthy controls, MDSCs were low for activated pSTAT1, suppressing in vitro alloresponses via IDO. In a separate study of 30 leukemia patients receiving allo-HCT, peripheral blood MDSC frequencies increased with acute GVHD compared with those without [45]. Notably, elimination or maturation of MDSC, with all-trans-retinoic acid or antibody-mediated depletion, significantly worsens GVHD. This observation helps explain the apparent contradiction that increased MDSCs are associated with increased pathology; the conclusion is that MDSC accumulation is dictated by the degree of inflammation, a reaction by the host to survive or at least temper the destructive process of GVHD [46].

GENERATION AND ADOPTIVE TRANSFER OF MDSCs TO PREVENT GVHD

MDSCs are rare and difficult to isolate from healthy donors. Although abundant in tumor-bearing hosts, repurposing tumor-derived MDSCs for therapeutic purposes would pose a risk. As a result of early studies investigating the ontogeny of MDSC in cancer models, cell culture methods have been developed to generate relatively large numbers of functional MDSCs from a variety of starting sources. Key cytokines and factors defined from the tumor microenvironment (G-CSF, GM-CSF, IL-13, IL-1β or IL-6, TNF-α, PGE2) have since been associated with the in vitro generation and expansion of MDSCs [47, 48]. For example, Zhou et al. [49] demonstrated that embryonic stem cells cultured for 17 d in c-kit ligand, VEGF, Flt3L, and thrombopoietin gave rise to CD11b+Gr1+ cells of either the CD115+Ly6C+ or CD115+Ly6C− subtype and express high iNOS and TGF-β mRNA levels; furthermore, M-CSF augmented these subsets. Moreover, CD115+ MDSCs suppressed acute GVHD lethality when adoptively transferred. Additionally, these investigators demonstrated that Lin− Sca1+ or Sca1− BM cells cultured for 8 d, as above, gave rise to CD115+Ly6C− suppressor cells (60% and 40%, respectively). In a related study, Highfill et al. [37] reported a simple and rapid GMP-compatible MDSC generation protocol using normal donor BM cultured for 4 d with GM-CSF and G-CSF, resulting in MDSCs that were CD11b+Gr1+ and coexpressed F4/80 (∼65%), Ly6C (∼70%), CD115 (∼40%), and IL-4Rα (∼60%). These MDSCs, when activated by the Th2 cytokine IL-13, gave rise to both ARG1 and iNOS-expressing and highly functional MDSC (Fig. 1C). The addition of IL-13 on d 3 did not substantially alter cell-surface antigens but did significantly increase in vitro suppressor cell function. MDSC expression of ARG1 is directly associated with limiting l-ARG bioavailability for responding T cells, resulting in reduced TCRζ expression and concomitant T cell dysfunction. In vivo, investigators have found that high ratios of MDSCs to donor T cells (3:1 or 4:1) are required to suppress GVHD [37, 49]. Such MDSC–IL-13 cells inhibited acute GVHD lethality in a CHOP and ARG1-dependent manner, whereas retained a GVL response to a lymphoma cell line given at the time of allo-HCT. Still others have found that GM-CSF, G-CSF, and IL-6 allowed a rapid generation of MDSCs from mouse and human BM precursors, giving rise to MDSCs with high-tolerogenic activity dependent on CHOP and linked to ARG1 and NOS2 expression [48]. Such cells were potent in suppressing pancreatic islet allograft rejection as well. In a xenogeneic mouse model using human umbilical cord blood, recombinant GM-CSF and G-CSF cytokines expanded myeloid cells with fibrocyte-associated markers, which through direct contact with responding T cells, produced IDO and tolerogenic T cells [50].

An important development in clinical translation was made by Lechner et al. [47], using peripheral blood exposed for 1 wk to various cytokines guided by RT-PCR analysis of 17 selected cancer cell lines that induce functionally suppressive CD33+ MDSCs in coculture studies. MDSC-inducing tumor cell lines showed increased expression of cyclooxygenase 2, IL-1β, IL-6, M-CSF, and IDO. The highest CD33+ suppressor cell function was noted with GM-CSF + IL-6 ± VEGF. Additional cytokines to promote MDSC function include, but are not limited to, IL-1β and TNF-α. Cytokine-induced CD33+ MDSCs up-regulated iNOS, TGF-β, and VEGF, contributing to their suppressor function, along with NOX2. Together, these studies point to an approach to generate donor MDSCs with improved function and survival that can be used for adoptive transfer to prevent GVHD. As alluded to, MDSC-mediated suppression has been shown to promote tumor growth, and whereas both granulocytic and monocytic subsets have been described as associated with various tumors, many reports suggest a preferential expansion of the granulocytic subset [51]. Therefore, it may be preferential to develop M-MDSCs for pursuit of therapeutic application, especially for preserving the GVL response. In addition, targeted antigen-specific suppression tailored to protect GVHD target organs, while preserving GVL responses, should be pursued.

Optimal MDSC suppression is desirable in controlling GVHD lethality, but given the variety of inducing factors and resultant heterogeneity, further study has been warranted. In a recent comparative study of BM-derived M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs, M-MDSCs were found to be more potently immune suppressive and in contrast to PMN-MDSCs, independent of the anti-apoptotic mitochrondrial death pathway, myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1. However, M-MDSCs were found to require continuous c-FLIP expression to prevent caspase-8-dependent cell death, indicating that whereas each subset may arise from similar factors, they are maintained independently via unique cell death pathways [52]. This work has implications for selective targeting of MDSC subsets that could be expanded or eliminated as needed for a given application. These and other cell death pathways are engaged during cellular responses to metabolic stress and have innate functions aimed at limiting host distress. For many cell types, this includes retreating to a quiescent state or even apoptosis. However, for cells of the immune system, these stresses can activate gene programs aimed at aiding recovery and limiting immune pathology. Myeloid cells, in particular, have recently been shown to activate autophagy programs and effectively avoid apoptosis in an high-mobility group box 1-dependent fashion [53]. This pathway aids tumor-associated MDSC survival and promotes tumor growth. Additional studies have implicated the death receptor, TNFR2, in support of MDSC survival, again through the induction of c-FLIP and the inhibition of caspase-8 activity [54]. Furthermore, in vivo CHOP expression in MDSCs can be induced by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and the C/EBP-β, leading to decreased IL-6 production and low pSTAT3 expression, suggesting a therapeutic potential for regulating CHOP in MDSCs [55]. MDSC survival was reduced by the endoplasmic reticulum stress response and also linked to caspase-8-mediated apoptosis via up-regulation of the death receptor 5. However, it was noted that MDSC loss was compensated by increased MDSC precursor proliferation, resulting in maintaining the elevated MDSC pool [56]. Accordingly, higher numbers of CD11b+Gr1+ cells with lower levels of caspase-3 are found in CHOP-deficient mice [55]. MDSC apoptosis can also be induced by cytotoxic T cells via Fas–FasL interaction [57]. Additional mediators for a delayed MDSC turnover in tumors include signaling mediated through the IL-4Rα [58] and decreased expression of the IFN-regulatory factor 8 [59].

UNIQUE ASPECTS OF ALLO-HCT RELEVANT TO IN VIVO MDSC SUPPRESSION MECHANISMS

Relative to lymphoid lineage cells, myeloid cells appear to have remarkable plasticity, making them hyper-responsive to environmental changes and difficult to characterize and track over time. Whereas this plasticity is a critical feature that benefits the host in countless ways, it poses a challenge when attempting to apply myeloid cells therapeutically and safely. This is even more pertinent for “immature” MDSCs that may have the potential to reverse course and become proinflammatory [60]. Under inflammatory conditions, lymphocyte development is suppressed, and myeloid development undergoes emergency granulopoiesis (Fig. 1D) [61]. Conditioning regimens, especially for hematologic malignancies, are disruptive/damaging and associated with necrotic cell death, and approaches that limit danger signals may promote/maintain MDSC function. Recently, we reported that in vitro-cultured MDSCs are responsive to the dramatic change in environment that they experience when adoptively transferred to a host undergoing acute GVHD [62]. Early post-transfer MDSCs convert to a DC-like phenotype that is inflammasome activated and associated with a loss of suppressor function (Fig. 1E). With the use of MDSCs genetically incapable of inflammasome activation (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a carboxy-terminal caspase activation and recruitment domain deficient), MDSCs could maintain suppressor function coupled with reduced GVHD-induced lethality. The observed loss of function in as few as 5 d post-transfer is problematic but also shows how important the very earliest interventions to T cell priming can significantly prolong survival. Encouragingly, multiple consecutive doses over the first week postallo-HCT dramatically improved survival, implying that the reintroduction of cultured MDSCs is a way of circumventing myeloid inflammasome conversion, maintaining function, and prolonging survival [62]. Such an approach also may give the endogenous MDSC response a chance to ramp up during the early post-transplant reconstitution phase. Consistent with these data, Ma et al. [63] showed that the differentiation of myeloid cells into proinflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory M2 or MDSC differentiation is regulated by PIR-B, also known as LILRB3. MDSCs genetically ablated for PIR-B underwent a specific transition to M1-like cells when entering the periphery from BM, resulting in decreased suppressive function, whereas activation of TLR STAT1 and NF-κB signaling in Lilrb3-deficient MDSCs promoted the acquisition of M1 phenotype. Thus, a major challenge for application of MDSC therapy will be addressing the inherent plasticity of myeloid lineage cells and ensuring they “do no harm” [64].

A series of papers from the Zeiser group [65–67] has demonstrated the dynamic role of inflammasome-activating components and pathways in enhancing GVHD. Prominent among these are the ATP-activated purinergic receptors P2x7 and P2y2, as well as the inflammasome-component nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich repeats family pyrin domain-containing 3 . These findings strongly implicate danger signals as a result of cell death, specifically, extracellular ATP, in promoting myeloid cell maturation and a cascade of events that feed back to promote inflammation in GVHD and are prime targets for potentially abrogating loss of function in adoptively transferred MDSCs. In that regard, small molecule inhibitors of inflammasome activation being developed for clinical use in several severe inflammatory diseases may be applicable for MDSC resistance to inflammasome activation [68, 69]. There are certainly other inflammatory mediators, as well as additional inflammasome-inciting signals present during the conditioning and development phases of GVHD that require further examination, but as yet, their role in MDSC development is unclear.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Whereas significant improvements have been made in the prevention and treatment of acute GVHD, mortality rates are still high; additionally, chronic GVHD presents another set of challenges that urgently require attention. The findings that G-CSF-induced stem cell mobilization was associated with an expansion of MDSC recruitment opened up the possibility that MDSCs could be promoted further for amelioration of GVHD. Subsequent studies have validated this approach and helped establish MDSC as a critical immune regulatory factor in limiting pathology. Whereas many features of myeloid cells and MDSC, in particular, remain cryptic as a result of their malleable nature, it is clear that they have a role to play. As cellular therapy advances in various forms toward clinical application, the promise of myeloid cell therapy will be an important component in the repertoire of clinicians.

AUTHORSHIP

B.H.K. and B.R.B. researched literature and cowrote the paper.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health Grants R01 HL56067, AI 34495, and HL1181879.

Glossary

- allo-HCT

allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation

- ARG1

arginase 1

- BM

bone marrow

- BMT

bone marrow transplant

- c-FLIP

cellular FLICE-like inhibitory protein

- CHOP

C/EBP-homologous protein

- DC

dendritic cell

- FADD

Fas-associated protein with death domain

- FasL

Fas ligand

- FLICE

FADD-like ICE (also known as Caspase 8)

- GVHD

graft-versus-host disease

- GVL

graft versus leukemia

- HO-1

heme oxygenase 1

- ICE

Interleukin-1 beta-converting enzyme

- LILRB3

leukocyte Ig-like receptor B3

- M-MDSC

monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- MDSC

myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- NOX2

NADPH oxidase

- PBSC

peripheral blood stem cell

- PIR-B

paired Ig-like receptor B

- PMN-MDSC

polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- pSTAT

phosphorylated STAT

- Treg

regulatory T cell

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

DISCLOSURES

B.H.K. and B.R.B. submitted the following U.S. patent: “GVHD-associated, Inflammasome-mediated Loss of Function in Adoptively Transferred Myeloid-derived Suppressor Cells.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Youn J.-I., Gabrilovich D. I. (2010) The biology of myeloid-derived suppressor cells: the blessing and the curse of morphological and functional heterogeneity. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 2969–2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murdoch C., Muthana M., Coffelt S. B., Lewis C. E. (2008) The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 618–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young M. R., Newby M., Wepsic H. T. (1987) Hematopoiesis and suppressor bone marrow cells in mice bearing large metastatic Lewis lung carcinoma tumors. Cancer Res. 47, 100–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seung L. P., Rowley D. A., Dubey P., Schreiber H. (1995) Synergy between T-cell immunity and inhibition of paracrine stimulation causes tumor rejection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 6254–6258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talmadge J. E., Gabrilovich D. I. (2013) History of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 739–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagaraj S., Gupta K., Pisarev V., Kinarsky L., Sherman S., Kang L., Herber D. L., Schneck J., Gabrilovich D. I. (2007) Altered recognition of antigen is a mechanism of CD8+ T cell tolerance in cancer. Nat. Med. 13, 828–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang L., DeBusk L. M., Fukuda K., Fingleton B., Green-Jarvis B., Shyr Y., Matrisian L. M., Carbone D. P., Lin P. C. (2004) Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell 6, 409–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bronte V., Brandau S., Chen S.-H., Colombo M. P., Frey A. B., Greten T. F., Mandruzzato S., Murray P. J., Ochoa A., Ostrand-Rosenberg S., Rodriguez P. C., Sica A., Umansky V., Vonderheide R. H., Gabrilovich D. I. (2016) Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nat. Commun. 7, 12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solito S., Bronte V., Mandruzzato S. (2011) Antigen specificity of immune suppression by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 90, 31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lees J. R., Azimzadeh A. M., Bromberg J. S. (2011) Myeloid derived suppressor cells in transplantation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 23, 692–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartung T. (1998) Anti-inflammatory effects of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 5, 221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mielcarek M., Graf L., Johnson G., Torok-Storb B. (1998) Production of interleukin-10 by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-mobilized blood products: a mechanism for monocyte-mediated suppression of T-cell proliferation. Blood 92, 215–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arpinati M., Green C. L., Heimfeld S., Heuser J. E., Anasetti C. (2000) Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor mobilizes T helper 2-inducing dendritic cells. Blood 95, 2484–2490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan L., Delmonte J. Jr., Jalonen C. K., Ferrara J. L. (1995) Pretreatment of donor mice with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor polarizes donor T lymphocytes toward type-2 cytokine production and reduces severity of experimental graft-versus-host disease. Blood 86, 4422–4429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng D., Dejbakhsh-Jones S., Strober S. (1997) Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor reduces the capacity of blood mononuclear cells to induce graft-versus-host disease: impact on blood progenitor cell transplantation. Blood 90, 453–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sloand E. M., Kim S., Maciejewski J. P., Van Rhee F., Chaudhuri A., Barrett J., Young N. S. (2000) Pharmacologic doses of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor affect cytokine production by lymphocytes in vitro and in vivo. Blood 95, 2269–2274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crough T., Nieda M., Nicol A. J. (2004) Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor modulates alpha-galactosylceramide-responsive human Valpha24+Vbeta11+NKT cells. J. Immunol. 173, 4960–4966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller J. S., Prosper F., McCullar V. (1997) Natural killer (NK) cells are functionally abnormal and NK cell progenitors are diminished in granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-mobilized peripheral blood progenitor cell collections. Blood 90, 3098–3105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morecki S., Gelfand Y., Yacovlev E., Eizik O., Shabat Y., Slavin S. (2008) CpG-induced myeloid CD11b+Gr-1+ cells efficiently suppress T cell-mediated immunoreactivity and graft-versus-host disease in a murine model of allogeneic cell therapy. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 14, 973–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joo Y.-D., Lee S.-M., Lee S.-W., Lee W.-S., Lee S.-M., Park J.-K., Choi I.-W., Park S.-G., Choi I., Seo S.-K. (2009) Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-induced immature myeloid cells inhibit acute graft-versus-host disease lethality through an indoleamine dioxygenase-independent mechanism. Immunology 128 (1 Suppl) e632–e640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacDonald K. P. A., Rowe V., Clouston A. D., Welply J. K., Kuns R. D., Ferrara J. L. M., Thomas R., Hill G. R. (2005) Cytokine expanded myeloid precursors function as regulatory antigen-presenting cells and promote tolerance through IL-10-producing regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 174, 1841–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perobelli S. M., Mercadante A. C. T., Galvani R. G., Gonçalves-Silva T., Alves A. P. G., Pereira-Neves A., Benchimol M., Nóbrega A., Bonomo A. (2016) G-CSF-induced suppressor IL-10+ neutrophils promote regulatory T cells that inhibit graft-versus-host disease in a long-lasting and specific way. J. Immunol. 197, 3725–3734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mielcarek M., Martin P. J., Torok-Storb B. (1997) Suppression of alloantigen-induced T-cell proliferation by CD14+ cells derived from granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-mobilized peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Blood 89, 1629–1634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bensinger W. I., Martin P. J., Storer B., Clift R., Forman S. J., Negrin R., Kashyap A., Flowers M. E., Lilleby K., Chauncey T. R., Storb R., Appelbaum F. R. (2001) Transplantation of bone marrow as compared with peripheral-blood cells from HLA-identical relatives in patients with hematologic cancers. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eapen M., Logan B. R., Confer D. L., Haagenson M., Wagner J. E., Weisdorf D. J., Wingard J. R., Rowley S. D., Stroncek D., Gee A. P., Horowitz M. M., Anasetti C. (2007) Peripheral blood grafts from unrelated donors are associated with increased acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease without improved survival. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 13, 1461–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luyckx A., Schouppe E., Rutgeerts O., Lenaerts C., Fevery S., Devos T., Dierickx D., Waer M., Van Ginderachter J. A., Billiau A. D. (2012) G-CSF stem cell mobilization in human donors induces polymorphonuclear and mononuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Clin. Immunol. 143, 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vendramin A., Gimondi S., Bermema A., Longoni P., Rizzitano S., Corradini P., Carniti C. (2014) Graft monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell content predicts the risk of acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic transplantation of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-mobilized peripheral blood stem cells. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 20, 2049–2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lv M., Zhao X. S., Hu Y., Chang Y. J., Zhao X. Y., Kong Y., Zhang X. H., Xu L. P., Liu K. Y., Huang X. J. (2015) Monocytic and promyelocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells may contribute to G-CSF-induced immune tolerance in haplo-identical allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am. J. Hematol. 90, E9–E16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Billiau A. D., Fevery S., Rutgeerts O., Landuyt W., Waer M. (2003) Transient expansion of Mac1+Ly6-G+Ly6-C+ early myeloid cells with suppressor activity in spleens of murine radiation marrow chimeras: possible implications for the graft-versus-host and graft-versus-leukemia reactivity of donor lymphocyte infusions. Blood 102, 740–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hongo D., Tang X., Baker J., Engleman E. G., Strober S. (2014) Requirement for interactions of natural killer T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells for transplantation tolerance. Am. J. Transplant. 14, 2467–2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lan F., Zeng D., Higuchi M., Higgins J. P., Strober S. (2003) Host conditioning with total lymphoid irradiation and antithymocyte globulin prevents graft-versus-host disease: the role of CD1-reactive natural killer T cells. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 9, 355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowsky R., Takahashi T., Liu Y. P., Dejbakhsh-Jones S., Grumet F. C., Shizuru J. A., Laport G. G., Stockerl-Goldstein K. E., Johnston L. J., Hoppe R. T., Bloch D. A., Blume K. G., Negrin R. S., Strober S. (2005) Protective conditioning for acute graft-versus-host disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 1321–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneidawind D., Baker J., Pierini A., Buechele C., Luong R. H., Meyer E. H., Negrin R. S. (2015) Third-party CD4+ invariant natural killer T cells protect from murine GVHD lethality. Blood 125, 3491–3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor P. A., Lees C. J., Blazar B. R. (2002) The infusion of ex vivo activated and expanded CD4(+)CD25(+) immune regulatory cells inhibits graft-versus-host disease lethality. Blood 99, 3493–3499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoffmann P., Ermann J., Edinger M., Fathman C. G., Strober S. (2002) Donor-type CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells suppress lethal acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J. Exp. Med. 196, 389–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen J. L., Trenado A., Vasey D., Klatzmann D., Salomon B. L. (2002) CD4(+)CD25(+) immunoregulatory T cells: new therapeutics for graft-versus-host disease. J. Exp. Med. 196, 401–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Highfill S. L., Rodriguez P. C., Zhou Q., Goetz C. A., Koehn B. H., Veenstra R., Taylor P. A., Panoskaltsis-Mortari A., Serody J. S., Munn D. H., Tolar J., Ochoa A. C., Blazar B. R. (2010) Bone marrow myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) inhibit graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) via an arginase-1-dependent mechanism that is up-regulated by interleukin-13. Blood 116, 5738–5747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turnquist H. R., Zhao Z., Rosborough B. R., Liu Q., Castellaneta A., Isse K., Wang Z., Lang M., Stolz D. B., Zheng X. X., Demetris A. J., Liew F. Y., Wood K. J., Thomson A. W. (2011) IL-33 expands suppressive CD11b+ Gr-1(int) and regulatory T cells, including ST2L+ Foxp3+ cells, and mediates regulatory T cell-dependent promotion of cardiac allograft survival. J. Immunol. 187, 4598–4610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matta B. M., Reichenbach D. K., Zhang X., Mathews L., Koehn B. H., Dwyer G. K., Lott J. M., Uhl F. M., Pfeifer D., Feser C. J., Smith M. J., Liu Q., Zeiser R., Blazar B. R., Turnquist H. R. (2016) Peri-alloHCT IL-33 administration expands recipient T-regulatory cells that protect mice against acute GVHD. Blood 128, 427–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reichenbach D. K., Schwarze V., Matta B. M., Tkachev V., Lieberknecht E., Liu Q., Koehn B. H., Pfeifer D., Taylor P. A., Prinz G., Dierbach H., Stickel N., Beck Y., Warncke M., Junt T., Schmitt-Graeff A., Nakae S., Follo M., Wertheimer T., Schwab L., Devlin J., Watkins S. C., Duyster J., Ferrara J. L. M., Turnquist H. R., Zeiser R., Blazar B. R. (2015) The IL-33/ST2 axis augments effector T-cell responses during acute GVHD. Blood 125, 3183–3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J., Ramadan A. M., Griesenauer B., Li W., Turner M. J., Liu C., Kapur R., Hanenberg H., Blazar B. R., Tawara I., Paczesny S. (2015) ST2 blockade reduces sST2-producing T cells while maintaining protective mST2-expressing T cells during graft-versus-host disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 308ra160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang D., Yu Y., Haarberg K., Fu J., Kaosaard K., Nagaraj S., Anasetti C., Gabrilovich D., Yu X.-Z. (2013) Dynamic change and impact of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in mice. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 19, 692–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guan Q., Blankstein A. R., Anjos K., Synova O., Tulloch M., Giftakis A., Yang B., Lambert P., Peng Z., Cuvelier G. D. E., Wall D. A. (2015) Functional myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets recover rapidly after allogeneic hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 21, 1205–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mougiakakos D., Jitschin R., von Bahr L., Poschke I., Gary R., Sundberg B., Gerbitz A., Ljungman P., Le Blanc K. (2013) Immunosuppressive CD14+HLA-DRlow/neg IDO+ myeloid cells in patients following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia 27, 377–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yin J., Wang C., Huang M., Mao X., Zhou J., Zhang Y. (2016) Circulating CD14(+) HLA-DR(−/low) myeloid-derived suppressor cells in leukemia patients with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: novel clinical potential strategies for the prevention and cellular therapy of graft-versus-host disease. Cancer Med. 5, 1654–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cuenca A. G., Delano M. J., Kelly-Scumpia K. M., Moreno C., Scumpia P. O., Laface D. M., Heyworth P. G., Efron P. A., Moldawer L. L. (2011) A paradoxical role for myeloid-derived suppressor cells in sepsis and trauma. Mol. Med. 17, 281–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lechner M. G., Liebertz D. J., Epstein A. L. (2010) Characterization of cytokine-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells from normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Immunol. 185, 2273–2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marigo I., Bosio E., Solito S., Mesa C., Fernandez A., Dolcetti L., Ugel S., Sonda N., Bicciato S., Falisi E., Calabrese F., Basso G., Zanovello P., Cozzi E., Mandruzzato S., Bronte V. (2010) Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression depend on the C/EBPbeta transcription factor. Immunity 32, 790–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou Z., French D. L., Ma G., Eisenstein S., Chen Y., Divino C. M., Keller G., Chen S.-H., Pan P.-Y. (2010) Development and function of myeloid-derived suppressor cells generated from mouse embryonic and hematopoietic stem cells. Stem Cells 28, 620–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zoso A., Mazza E. M. C., Bicciato S., Mandruzzato S., Bronte V., Serafini P., Inverardi L. (2014) Human fibrocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells express IDO and promote tolerance via Treg-cell expansion. Eur. J. Immunol. 44, 3307–3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Youn J.-I., Nagaraj S., Collazo M., Gabrilovich D. I. (2008) Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J. Immunol. 181, 5791–5802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haverkamp J. M., Smith A. M., Weinlich R., Dillon C. P., Qualls J. E., Neale G., Koss B., Kim Y., Bronte V., Herold M. J., Green D. R., Opferman J. T., Murray P. J. (2014) Myeloid-derived suppressor activity is mediated by monocytic lineages maintained by continuous inhibition of extrinsic and intrinsic death pathways. Immunity 41, 947–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parker K. H., Horn L. A., Ostrand-Rosenberg S. (2016) High-mobility group box protein 1 promotes the survival of myeloid-derived suppressor cells by inducing autophagy. J. Leukoc. Biol. 100, 463–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao X., Rong L., Zhao X., Li X., Liu X., Deng J., Wu H., Xu X., Erben U., Wu P., Syrbe U., Sieper J., Qin Z. (2012) TNF signaling drives myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 4094–4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thevenot P. T., Sierra R. A., Raber P. L., Al-Khami A. A., Trillo-Tinoco J., Zarreii P., Ochoa A. C., Cui Y., Del Valle L., Rodriguez P. C. (2014) The stress-response sensor chop regulates the function and accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumors. Immunity 41, 389–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Condamine T., Kumar V., Ramachandran I. R., Youn J.-I., Celis E., Finnberg N., El-Deiry W. S., Winograd R., Vonderheide R. H., English N. R., Knight S. C., Yagita H., McCaffrey J. C., Antonia S., Hockstein N., Witt R., Masters G., Bauer T., Gabrilovich D. I. (2014) ER stress regulates myeloid-derived suppressor cell fate through TRAIL-R-mediated apoptosis. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 2626–2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sinha P., Chornoguz O., Clements V. K., Artemenko K. A., Zubarev R. A., Ostrand-Rosenberg S. (2011) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells express the death receptor Fas and apoptose in response to T cell-expressed FasL. Blood 117, 5381–5390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roth F., De La Fuente A. C., Vella J. L., Zoso A., Inverardi L., Serafini P. (2012) Aptamer-mediated blockade of IL4Rα triggers apoptosis of MDSCs and limits tumor progression. Cancer Res. 72, 1373–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Waight J. D., Netherby C., Hensen M. L., Miller A., Hu Q., Liu S., Bogner P. N., Farren M. R., Lee K. P., Liu K., Abrams S. I. (2013) Myeloid-derived suppressor cell development is regulated by a STAT/IRF-8 axis. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 4464–4478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nefedova Y., Fishman M., Sherman S., Wang X., Beg A. A., Gabrilovich D. I. (2007) Mechanism of all-trans retinoic acid effect on tumor-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 67, 11021–11028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kondo M. (2010) Lymphoid and myeloid lineage commitment in multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. Immunol. Rev. 238, 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koehn B. H., Apostolova P., Haverkamp J. M., Miller J. S., McCullar V., Tolar J., Munn D. H., Murphy W. J., Brickey W. J., Serody J. S., Gabrilovich D. I., Bronte V., Murray P. J., Ting J. P.-Y., Zeiser R., Blazar B. R. (2015) GVHD-associated, inflammasome-mediated loss of function in adoptively transferred myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Blood 126, 1621–1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ma G., Pan P.-Y., Eisenstein S., Divino C. M., Lowell C. A., Takai T., Chen S.-H. (2011) Paired immunoglobin-like receptor-B regulates the suppressive function and fate of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Immunity 34, 385–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rathinam V. A. K., Vanaja S. K., Fitzgerald K. A. (2012) Regulation of inflammasome signaling. Nat. Immunol. 13, 333–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jankovic D., Ganesan J., Bscheider M., Stickel N., Weber F. C., Guarda G., Follo M., Pfeifer D., Tardivel A., Ludigs K., Bouazzaoui A., Kerl K., Fischer J. C., Haas T., Schmitt-Gräff A., Manoharan A., Müller L., Finke J., Martin S. F., Gorka O., Peschel C., Ruland J., Idzko M., Duyster J., Holler E., French L. E., Poeck H., Contassot E., Zeiser R. (2013) The Nlrp3 inflammasome regulates acute graft-versus-host disease. J. Exp. Med. 210, 1899–1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilhelm K., Ganesan J., Müller T., Dürr C., Grimm M., Beilhack A., Krempl C. D., Sorichter S., Gerlach U. V., Jüttner E., Zerweck A., Gärtner F., Pellegatti P., Di Virgilio F., Ferrari D., Kambham N., Fisch P., Finke J., Idzko M., Zeiser R. (2010) Graft-versus-host disease is enhanced by extracellular ATP activating P2X7R. Nat. Med. 16, 1434–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Klämbt V., Wohlfeil S. A., Schwab L., Hülsdünker J., Ayata K., Apostolova P., Schmitt-Graeff A., Dierbach H., Prinz G., Follo M., Prinz M., Idzko M., Zeiser R. (2015) A novel function for P2Y2 in myeloid recipient-derived cells during graft-versus-host disease. J. Immunol. 195, 5795–5804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Youm Y.-H., Nguyen K. Y., Grant R. W., Goldberg E. L., Bodogai M., Kim D., D’Agostino D., Planavsky N., Lupfer C., Kanneganti T. D., Kang S., Horvath T. L., Fahmy T. M., Crawford P. A., Biragyn A., Alnemri E., Dixit V. D. (2015) The ketone metabolite β-hydroxybutyrate blocks NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammatory disease. Nat. Med. 21, 263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Coll R. C., Robertson A. A. B., Chae J. J., Higgins S. C., Muñoz-Planillo R., Inserra M. C., Vetter I., Dungan L. S., Monks B. G., Stutz A., Croker D. E., Butler M. S., Haneklaus M., Sutton C. E., Núñez G., Latz E., Kastner D. L., Mills K. H. G., Masters S. L., Schroder K., Cooper M. A., O’Neill L. A. J. (2015) A small-molecule inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Nat. Med. 21, 248–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]