Review on the interaction of matrix components and immune infiltrate in myeloma, a key determinant in immunotherapy.

Keywords: immunotherapy, immunoregulation, microenvironment, macrophages, dendritic cells

Abstract

The last 10–15 years have witnessed a revolution in treating multiple myeloma, an incurable cancer of Ab-producing plasma cells. Advances in myeloma therapy were ushered in by novel agents that remodel the myeloma immune microenvironment. The first generation of novel agents included immunomodulatory drugs (thalidomide analogs) and proteasome inhibitors that target crucial pathways that regulate immunity and inflammation, such as NF-κB. This paradigm continued with the recent regulatory approval of mAbs (elotuzumab, daratumumab) that impact both tumor cells and associated immune cells. Moreover, recent clinical data support checkpoint inhibition immunotherapy in myeloma. With the success of these agents has come the growing realization that the myeloid infiltrate in myeloma lesions—what we collectively call the myeloid-in-myeloma compartment—variably sustains or deters tumor cells by shaping the inflammatory milieu of the myeloma niche and by promoting or antagonizing immune-modulating therapies. The myeloid-in-myeloma compartment includes myeloma-associated macrophages and granulocytes, dendritic cells, and myeloid-derived-suppressor cells. These cell types reflect variable states of differentiation and activation of tumor-infiltrating cells derived from resident myeloid progenitors in the bone marrow—the canonical myeloma niche—or myeloid cells that seed both canonical and extramedullary, noncanonical niches. Myeloma-infiltrating myeloid cells engage in crosstalk with extracellular matrix components, stromal cells, and tumor cells. This complex regulation determines the composition, activation state, and maturation of the myeloid-in-myeloma compartment as well as the balance between immunogenic and tolerogenic inflammation in the niche. Redressing this balance may be a crucial determinant for the success of antimyeloma immunotherapies.

Introduction

Myeloma, a tumor of plasma cells [1], occupies a unique position among the spectrum of hematologic malignancies. First, the widespread numerical and structural chromosomal abnormalities found early in its natural history set it apart from other hematopoietic neoplasms [2–4]. Indeed, myeloma is a hematopoietic malignancy with carcinoma-like (cyto)genetics. Second, myeloma tumors are organized in a spatially and structurally organized manner that is reminiscent of solid tumors [5–9]. Malignant plasma cells are typically dependent on support from their microenvironment—often, but not always, the bone marrow—and do not readily survive outside their physiologic niches. Third, myeloma tumors in the bone marrow are often organized as discrete foci/clusters with interspersed morphologically normal marrow: their orderly dissemination in the marrow space has been hypothesized to bear many parallels to solid tumor metastasis [10].

Normal counterparts of myeloma cells are the long-lived, antigen-experienced, isotype-switched plasma cells that secrete Ab. Mature plasma cells are derived from committed plasmablasts that develop in secondary lymphoid tissues—spleen, lymph nodes—as products of germinal center reactions that generate Ab affinity maturation [4]. Commitment to plasma cell fate is heralded by expression of the transcription factor PRDM1 (Blimp-1) [11]. Following lineage commitment, plasmablasts migrate to the bone marrow via chemokine-driven networks [12] where they mature into nondividing, long-lived, Ab-secreting plasma cells.

The myeloma cell of origin is enigmatic but available evidence allows the formulation of solid hypotheses. Early, perhaps initiating, primary translocations juxtapose cyclin D genes or their upstream regulators [13] with powerful regulatory elements within the IgH locus on chromosome 14q. Primary translocations exhibit breakpoints that are characteristic of isotype-switch recombination, a process that is generally thought to occur in antigen-experienced B centroblasts and/or centrocytes [2, 13] within germinal centers. Whereas primary oncogenic events may occur in cells that are not committed to a plasma cell fate [i.e., before PRDM1 (Blimp-1) induction], it is likely that secondary mutations (e.g., RAS mutations [14]; see below) most commonly occur in plasmacytic lineage-committed cells. Rasmussen et al. [15] examined purified cell populations from RAS-mutant myeloma tumors. They detected products of primary translocations, but not RAS mutations, in flow-sorted memory B cells. RAS mutations were only detected in malignant plasma cells from the same patient.

Comprehensive mutational profiling of myeloma was carried out by Chapman et al. [16] and Lohr et al. [17]. Several consistent themes have emerged from these analyses: myeloma tumors carry recurrent mutations in MAPK pathway genes (KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF); mutations that affect protein translation and its quality control are common (LRRK2, XBP1); other recurrent mutations dysregulate upstream components of the NF-κB pathway (BTRC, CARD11, CYLD, IKBIP, IKBKB, MAP3K1, MAP3K14, RIPK4, TLR4, TNFRSF1A, and TRAF3) and chromatin-modifying enzymes (MLL, MLL2, MLL3, UTX, WHSC1, and WHSC1L1), as well as RNA processing catalysts (DIS3). Of interest, recurrent mutations were identified in the CCND1 locus, which is the target of t(11;14) translocation.

The complex cytogenetic and mutational profile of myeloma tumors likely generates an extensive neoantigenic repertoire that can only be tolerated via induction of profound immune dysfunction [18]. In fact, progressive immune deficiencies, rather than cell-autonomous clonal evolution, can be hypothesized to underlie the progression from asymptomatic MGUS to symptomatic myeloma, given the similarity in genetic composition between MGUS and myeloma. Myeloma has been categorized as a disease of intermediate mutational burden [19]; however, it is likely that genetic high-risk myeloma subsets (e.g., TP53-mutant myeloma [20, 21]) bear significantly higher mutational loads that approximate those of carcinogen-driven tumors, such as melanoma and lung carcinoma. High mutational burden may be associated with T cell inflammation and hallmarks of immune dysfunction, such as activation of inhibitory PD-1–dependent networks [22]. Conversely, immune cells may promote genetic instability in a bidirectional fashion: DCs that infiltrate myeloma lesions may reactivate dormant mechanisms of genetic instability in malignant plasma cells [23]. Immunosuppression accompanies chronic inflammation that provides trophic and survival support to myeloma cells through induction of such pathways as NF-κB, MAPK, and JAK/STAT [24, 25]. Thus, the success of a nascent myeloma lesion requires radical alterations in the local inflammatory and immune milieu. In this review, we shall focus on crosstalk between ECM and immune cells of myeloid origin in the myeloma niche.

MATRIX AND IMMUNOREGULATION IN THE MYELOMA NICHE

Canonical and noncanonical myeloma niches

The general notion of myeloma as a bone marrow–based disease has given rise to the concept of the canonical myeloma niche where bone-specific elements—osteoblasts, osteocytes, and osteoclasts—exert trophic and regulatory support to the myeloma tumor cell [26]. However, extramedullary myeloma and plasmacytoma tumors are not uncommon [27, 28]. In fact, the incidence of extramedullary disease may have increased in the era of novel agents [29, 30]. Extramedullary disease suggests that malignant plasma cells can also thrive in noncanonical niches where bone-specific elements are absent.

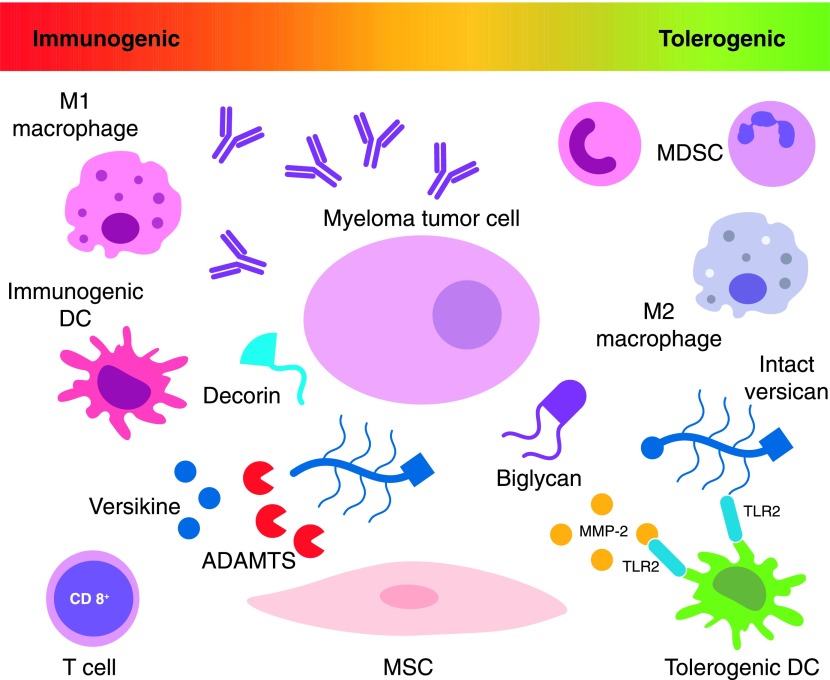

Therefore, the minimum requirements for an operative myeloma niche, in addition to the tumor cell, are stromal-lineage cells and immune regulatory cells as well as blood vessels and matrix (Fig. 1). In this schema, the canonical osteocentric niche may be seen as a variation of the universal niche. We have hypothesized that ECM, stromal fibroblasts, and infiltrating immune cells constitute the common denominator between canonical and noncanonical niches [31]. Thus, interplay between matrix elements and immune-infiltrating cells may be essential to sustain myeloma cells through regulation of tumor-promoting inflammation and immunosurveillance.

Figure 1. Interplay between infiltrating myeloid cells, ECM, stromal cells, and tumor cells shapes the inflammatory milieu of the myeloma niche and regulates the profound immune dysfunction associated with myeloma progression.

Success of immunotherapeutic strategies to control and hopefully eradicate myeloma will necessitate overcoming immunosuppressive barriers and redressing the balance between immunogenic and tolerogenic inflammation in the niche. MSC = mesenchymal stem cell.

Myeloma matrisome

The importance of tumor ECM remodeling in cancer progression and invasion is undisputed [32]. Tumor interstitial matrix consists of collagens, glycoproteins, matrix proteoglycans, and glycosaminoglycans [33]. Together with ECM accessory proteins and remodeling enzymes, they constitute a functional unit that coordinates tumor invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, and immunoregulation [34, 35]. Matrix remodeling has been hypothesized to contribute to disease progression from an asymptomatic MGUS stage to symptomatic myeloma [36]. Slany and colleagues took a systematic discovery proteomic approach to investigate the changes in matrix composition upon myeloma progression [36]. They evaluated ECM proteins, ECM receptors, and ECM-modulating enzymes in cytoplasmic, nuclear, and secreted fractions from fibroblast-like cells that were isolated from normal, MGUS, and myeloma bone marrow aspirates. Hits that were associated with disease progression included secreted components, such as the proteoglycan biglycan, laminin subunit α4, MMP-2, nidogen-2, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (also known as endothelial plasminogen activator inhibitor or serpin E1), and the growth factor periostin. Intracellular proteins that increased upon disease progression included, lysyl-hydroxylase 2, prolyl 4-hydroxylase 1, and basigin. Cell-surface receptors that were identified included integrin α5β5, C-type mannose receptor 2, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β. ECM components that were down-regulated during myeloma progression included secreted proteins, such as chitinase-3-like protein 1, protein-lysine 6-oxidase, and fibulin-2. The latter was completely absent in both MGUS and symptomatic myeloma compared with normal.

Of note, this study focused on stromal cell–derived proteins on the basis of the hypothesis that stromal cells may be the primary producers of ECM components. Understanding of the myeloma matrisome will need to be completed by investigating matrix components that may be produced by infiltrating hematopoietic cells in the myeloma niche and perhaps also by tumor cells.

Matrix proteoglycans and myeloma niche immunoregulation

Slany et al. detected a strong association between biglycan secretion and myeloma progression [36]. Biglycan is an SLRP that is cleaved off the ECM via action of proteases, including bone morphogenetic protein-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-13, and granzyme B [37, 38]. Biglycan is a prototypical ECM-derived DAMP [37]. During inflammatory reactions, liberated biglycan acts as an endogenous ligand of TLR2/4 to trigger downstream inflammatory pathways. Biglycan also acts as an amplifier of inflammation via facilitating NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated IL-1β maturation and release [39]. Another SLRP, decorin, also acts via TLR2/4, but its downstream pathways seem to have evolved in a divergent fashion than those activated by biglycan: decorin may promote immunogenic inflammation through inhibitory actions on TGF-β1 [40]. Indeed, decorin may act as an antagonist to myeloma growth [41]. Consistent with this hypothesis, decorin production is decreased with myeloma progression [41]. Another SLRP, lumican, may act as a facilitator of pathogen-associated molecular patterns, rather than as an autonomous DAMP [42]. Lastly, the proteoglycan serglycin was recently reported to be abundantly produced by myeloma cells and secreted in the extracellular space [43]. Knockdown of serglycin had a significant growth inhibitory effect in tumors growing in immunodeficient mice [44]—its roles in myeloma niche immunoregulation are less clear.

In addition to liberating SLRP, matrix proteases cleave large matrix proteoglycans, such as versican, to generate bioactive fragments [45, 46]. Versican is a chrondroitin-sulfate proteoglycan that belongs to the lectican (or hyalectan) family that also includes aggrecan (abundant in cartilage), brevican, and neurocan (nervous system proteoglycans). Versican accumulates at sites of cancerous and noncancerous inflammation and is thought to act as an inflammation amplifier that promotes recruitment and activation of myeloid-infiltrating cells [47–55]. Of importance, the Cattral group recently demonstrated that, in addition to tumor-sustaining inflammation, versican is immunosuppressive and acts via TLR2 to cause DC dysfunction [56].

We and others have demonstrated that versican accumulates in myeloma tumors where it may activate myeloid cells via TLR2/6 heterodimers [57, 58]. Moreover, we detected evidence of in situ versican proteolysis at sites consistent with active ADAMTS-type metalloproteinases [59]. This observation raised 3 alternative (or complementary) hypotheses: first, versican proteolysis may regulate local versican abundance; second, proteolysis might disrupt versican’s established multimolecular networks (e.g., with hyaluronic acid or tenascin C [60]); and third, versican proteolysis may serve to generate novel bioactive fragments. A bioactive fragment (versikine), generated via proteolytic degradation by ADAMTS proteases at Glu441-Ala442 of the versican V1-isoform was previously implicated in morphogenesis and development [45, 46]. We recently showed that versikine acts as a novel DAMP. Versikine triggers an as yet-incompletely-defined transcriptional program that culminates in IRF8-dependent type-I IFN signatures in myeloid cells and IL-12p40, but not IL-10, induction [59]. These collective actions of versikine are predicted to promote antitumor immunogenicity and thus antagonize the tolerogenic actions of intact versican. The versican-versikine axis may constitute a key component of a tightly regulated network, implicating both large and small matrix proteoglycans in tumor immunosurveillance. On the therapeutic front, matrix-derived DAMPs could gain an important role in modern combinatorial immunotherapy [61], either as novel vaccine adjuvants or, potentially, encoded within (and secreted from) armored engineered effector cells (e.g., armored CAR-T [62]).

Matrix-remodeling proteases: mediators of crosstalk between matrix and immune cells

MMPs have crucial roles in regulating ECM composition and turnover [32]. Their roles in immunoregulation are beginning to be elucidated [35]. Matrix-remodeling proteases from MMP, ADAM, and ADAMTS, as well as cathepsin and elastase families and their inhibitors are produced by infiltrating myeloid cells, stromal cells, and/or tumor cells in a tumor type– and context-specific fashion [32, 63, 64]. TIMP-1, -2, -3, and -4 form 1:1 stochiometric complexes with active MMPs, thus fine-tuning proteolytic activity. Macrophages, MDSCs, tumor-infiltrating neutrophils, and even DCs have been reported to participate in this regulation [64]. The specific cellular source of each protease/inhibitor pair can have profound consequences on their function and activity; for example, neutrophil-derived MMP-9, which lacks bound TIMP-1, is more activatable and potent than MMP-9/TIMP-1 complexes that are naturally produced by monocytic cells and mesenchymal origin cells [65].

In myeloma, metalloproteinases from the MMP and ADAMTS families are dysregulated and contribute to disease progression via both proteolysis-dependent and -independent activities [66]. In an immunocompetent murine myeloma model, broad pharmacologic MMP inhibition led to reduction in tumor burden, decreased neovascularization, and partial protection against bone lytic disease [67].

Several reports have implicated MMP-2 in myeloma progression [68–70]. Myeloma-associated stromal cells expressed pro–MMP-2 that was converted into active MMP-2 enzyme after coculture with myeloma cells [71], and this activity was mediated through MMP-7 that was secreted by myeloma cells [72]. Of importance, the Bhardwaj group recently reported that MMP-2 acts as a TLR2 ligand in DCs, promoting protumorigenic DC polarization and Th2 differentiation [73]. Whether this pathway intersects with the versican-TLR2 pathway is unclear.

Whereas MMP-2 is expressed by stromal cells, myeloma cells themselves express MMP-9 [71]. Decreased MMP-9 was associated with elevated syndecan-1 and with higher marrow plasmacytosis, serum β-2 microglobulin, and paraprotein levels [74]. Both MMP-9 and MMP-2 were induced in myeloma cells via interaction of cell-surface serglycin with collagen I, a major bone matrix component [43]. MMP-9 in myeloma cells was also induced via interaction with endothelial cells [75]. This interaction promoted myeloma cell invasiveness [76].

Another MMP expressed by myeloma cells, MMP-13, promotes osteolysis in a protease-independent manner. In particular, MMP-13 enhances osteoclast multinucleation and bone-resorptive activity by triggering up-regulation of the cell fusogen DC-STAMP [77]. Moreover, as mentioned in the Matrix proteoglygans and myeloma niche immunoregulation section in this article, MMP-13 is a protease that cleaves off biglycan. Thus, MMP-13 may contribute to myeloma progression through both protease-dependent and protease-independent activities.

The Klein group undertook a systematic survey of expression of ADAM and ADAMTS proteases and their endogenous inhibitors in multiple myeloma [78]. ADAMTS9 was aberrantly expressed by primary malignant plasma cells, and ADAM23 expression was associated with inferior prognosis. ADAMTS9 is a versican-degrading enzyme [79]. ADAMTS1 was expressed by bone marrow stromal cells—a result that also corroborated our data [59]. ADAM17 (TACE) regulates TNF-α secretion under the control of TPL2-mediated ERK phosphorylation [80], which suggested that ADAM-type proteases may regulate macrophage polarization in the myeloma niche via additional actions on nonmatrix substrates [81].

Collagen and collagen-derived matrikines

Collagen is a major component of bone tissue and its turnover in myeloma has mainly been studied in the context of osteolysis [82]; however, collagen has immunoregulatory activities. Collagen I exerts an inhibitory effect on immune cells that is likely mediated by its binding with the leukocyte-associated Ig-like receptors, which are expressed at the surface of most immune cells [83]. Bioactive collagen fragments (matrikines) are chemotactic, and their activity may reside in a structural relatedness to CXC chemokines: N-acetyl-Pro-Gly-Pro, most likely derived from collagen breakdown, caused chemotaxis and production of superoxide via CXC receptors [84]. Moreover, distinct collagen fragments can either augment or suppress IL-1β production from human peripheral blood monocytes [85]. Collagen affects immune cell regulation. For example, collagen VI is critical for macrophage migration and polarization during peripheral nerve regeneration [86]. Culture on collagen-coated surfaces modulates macrophage polarization [87]. Exposure to type I collagen induces maturation of mouse liver DC progenitors [88]. Activation of collagen receptor DDR1 can promote macrophage infiltration in atherosclerotic plaques [89].

Matrix glycoproteins in myeloma-related homeostasis and inflammation

Tenascin C, extravascularly deposited fibrinogen, and the MMP-cleaved extra domain A of fibronectin act as DAMPs via TLR4 [37]. Tenascin C aggravates autoimmune myocarditis via DC activation and Th17 cell differentiation [90]. Analogous mechanisms operate in autoimmune arthritis [91]. An earlier study detected strong expression of tenascin C in the myeloma bone marrow [92]. Adhesion of myeloma-cultured cells to tenascin C was weak; however, the immune regulatory properties of tenascin C may be more important than tumor cell adhesion. Adhesion of myeloma cells to fibronectin has been proposed to be induced by RAS mutations and to contribute to chemoresistance [93].

Levels of the matrix glycoprotein SPARC (secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine) are reduced in advanced myeloma [94]. Mice that lack SPARC have an altered distribution of macrophages in tumors [95], which suggests that matrix glycoprotein composition may affect immune cell infiltration in myeloma tumors.

Reelin, another ECM glycoprotein that is highly expressed in myeloma, promoted adhesion of myeloma cells to fibronectin via activation of α5β1 integrin, which resulted in focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation [96]. Recently, focal adhesion kinase inhibition was shown to render pancreatic cancers responsive to checkpoint inhibition immunotherapy [97].

Matrix- and receptor-associated glucosaminoglycans in myeloma

Hyaluronan is a linear high-MW glycosaminoglycan that is widely distributed in the ECM. Hyaluronan binds versican as well as link protein in large multimolecular complexes [46]. Expression of hyaluronan synthases (HAS1, HAS2, and HAS3) is increased in inflammatory conditions and tumors [98]. Full-length and splice variants of HAS1 are prevalent in myeloma [99].

Hyaluronidases that are often produced by tumor cells break down hyaluronan, which results in the release of low-MW soluble fragments that act as DAMPs via TLR4 [37]. Taylor et al. showed that low-MW hyaluronan activates TLR4 signaling via a novel coreceptor complex that involves TLR4, MD-2, and CD44 [100]. Plasma hyaluronidase activity was found to be significantly elevated in patients with monoclonal gammopathy vs. normal controls [101]. Hyaluronan receptors have been implicated in myeloma pathogenesis. Engagement of CD44 by hyaluronic acid promotes dexamethasone and lenalidomide resistance in myeloma cells [102, 103]. Another hyaluronan receptor, RHAMM, is aberrantly expressed in myeloma cells upon disease progression [104].

Free HS is released into the extracellular space through the actions of heparanase enzymes [105]. HS is cleaved off transmembrane receptor glycosaminoglycans, such as syndecans and GPI-anchored glypicans. Free HS can interact with TLR4 and mediate DC maturation [106]. High heparanase correlates with poor prognosis in multiple myeloma and other cancers [107–110]. A major target is the HS proteoglycan syndecan-1 or CD138, which is abundantly expressed on the surface of normal and malignant plasma cells [111]. The Rapraeger group showed that HS trimming by heparanase is followed by MMP-9–mediated shedding of syndecan-1 [112]. This exposes a juxtamembrane site that binds VEGFR2 and VLA-4, which couples VEGFR2 to the integrin. Shed syndecan-1 acts via VEGFR2 activation to promote myeloma cell migration and invasion. Peptides called synstatins that contain only the VLA-4 or VEGFR2 binding sites competitively inhibit invasion by blocking the coupling of receptors [112]. Synstatins have also been designed to block IGFR1 capture by syndecan-1 [113]. This mechanism delivers an antiapoptotic signal to myeloma cells. Thus, IGFR1-targeting synstatins cause myeloma cell demise.

THE MYELOID-IN-MYELOMA COMPARTMENT: REGULATORS OF INFLAMMATION AND ANTITUMOR IMMUNITY

MDSCs in myeloma

Accumulation of immature MDSCs with potent T cell suppressive activity underlies immune dysfunction in several cancers and provides a strategic target for therapeutic intervention [114–118]. In myeloma, increased monocytic CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs were initially reported in peripheral blood mononuclear fractions of human patients at diagnosis [119]. These early data were followed by reports that showed a significant increase in PMN-MDSCs in the blood and bone marrow of human patients with progressive myeloma [120–122]. The Nefedova group dissected relevant mechanisms in in vivo immunocompetent models. S100A9 knockout mice, which are deficient in their ability to accumulate MDSCs in tumor-bearing hosts, demonstrated reduced MDSC accumulation in bone marrow after injection of myeloma cells compared with wild-type mice. Growth of immunogenic myeloma cells was significantly reduced in S100A9 knockout mice [121]. MDSC accumulation was also found to be reflected in the 5TMM myeloma model [123]. Mechanistic work in this model demonstrated the importance of myeloma-induced Mcl-1 for MDSC survival [124]. Stromal cells may also play key roles in educating MDSCs as only myeloma-derived, stromal-educated MDSCs displayed suppressive activities [125]. Education may be mediated via exosome-mediated cell-to-cell communication [126].

MDSCs may promote myeloma via activities that are independent of their immunosuppressive roles. A recent report showed that PMN-MDSCs may promote myeloma through proangiogenic functions [127]. Moreover, PMN-MDSCs were found to protect myeloma cells from chemotherapy-induced damage, thus providing additional rationale for therapeutic targeting [128].

Manipulating the MDSC compartment is generally achieved via depletion or interference with their function. Lenalidomide, a prime antimyeloma agent, impacts MDSC homeostasis and function [129]. The recently approved αCD38 mAb daratumumab likely exerts inhibitory effects on CD38-expressing MDSCs in addition to its binding of CD38-expressing myeloma cells [130]. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition was shown to reverse MDSC-mediated immune dysfunction in experimental animal models and in humans [131, 132]. The observation that addition of the phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor, tadalafil, in a patient with end-stage relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma reduced MDSC function and generated a dramatic and durable antimyeloma immune and clinical response provided the rationale for clinical testing across tumor types [133].

DC dysfunction in myeloma

DC dysfunction confers immunologic privilege to the growing myeloma tumor. Low DC numbers as well as functional impairment contribute to myeloma immunoparesis [119]. The Joshua group showed that human myeloma-derived DCs failed to up-regulate CD80 expression in response to huCD40 ligand, likely under the influence of tumor-derived factors, such as TGF-β1 and IL-10 [134]. IL-6 and VEGF have been also implicated in DC dysfunction [135, 136]. Leone et al. tested the hypothesis that DC dysfunction accounts for disease progression from asymptomatic to overt myeloma, demonstrating dual roles of DCs in presenting tumor antigen while progressively down-regulating proteasome activity in malignant plasma cells, which contributes to immunologic escape [137].

Defects in DC differentiation are also postulated to play a role in myeloma immune dysfunction. Immature DCs induce clonogenic growth of malignant plasma cells while displaying osteoclast-like features, including the ability to resorb bone tissue once cultured with myeloma cells [138].

Murine myeloma-conditioned media caused p38 MAPK-mediated DC dysfunction [139]. This dysfunction manifested as defects in expression of maturation/activation antigens as well as a compromised capacity to activate allospecific T cells. Inhibition of p38 MAPK restored the phenotype, cytokine secretion, and function of conditioned media–impaired DCs [140].

Conversely, agents that provoke immunogenic cell death that are commonly used in myeloma, such as the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, may act to restore DC functionality [141], although certain subsets may be adversely affected [142]. In the study by Spisek et al. [141], engulfment of human myeloma cells by DCs after tumor cell death by bortezomib, but not γ-irradiation or steroids, led to induction of potent antitumor immunity. This effect depended on cell-cell contact between DCs and dying tumor cells and was mediated by bortezomib-induced exposure of hsp90 on the surface of dying cells. Thalidomide analogs also enhance DC maturation and promote antigen cross-presentation [143–145].

pDCs in myeloma have received much less attention than conventional DCs. By using xenograft approaches, the Anderson group reported that pDCs mediated immune deficiency characteristic of myeloma and promoted myeloma cell growth, survival, and drug resistance. Treatment with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides restored pDC immune function and abrogated pDC-induced myeloma cell growth [146].

On the therapeutic front, fusion of myeloma cells with DCs results in functional maturation and cross-presentation of a broad antigenic repertoire [147]. Phase II data on myeloma-DC fusion vaccination after autologous transplantation support further enthusiasm for this approach [148]. In this study, 24 patients received serial vaccinations with DC/myeloma fusion cells post-transplant. A second cohort of 12 patients additionally received pretransplant vaccine. Seventy-eight percent of patients achieved a best response of CR plus very good partial response, and 47% achieved a CR/near CR. DCs were generated from adherent mononuclear cells that were cultured with GM-CSF, IL-4, and TNF-α before fusion with autologous bone marrow–derived myeloma cells. Despite the encouraging results, GM-CSF plus IL-4 may not provide the optimal DC-differentiation stimulus compared with flt3L-based approaches.

Tumor-associated macrophages and neutrophils in myeloma

Tumor-associated macrophages in myeloma are a relative latecomer in our understanding of the immunologic make-up of the myeloma niche; however, their importance is paramount because they constitute a significant proportion of myeloma tumor cellularity (5–10% in most cases) [149]. Tumor-associated macrophages in myeloma are a long-standing focus of our laboratory and were recently reviewed by our group [31] and others [150]. We shall focus here on some noteworthy advances with significant prognostic and therapeutic implications that have been reported since we last reviewed the topic in 2013 [31].

An important study corroborated the prognostic importance of macrophage infiltration in human myeloma. Of importance, this study also implicated CD147, an ECM metalloproteinase inducer (EMMPRIN) [151]. Chemokines were shown to play an important role not only in monocytic cell recruitment but also in polarization at the myeloma tumor site: CCL3, CCL14, and CCL2 were recently shown to play key roles in this process [152]. Moreover, myeloma cells were shown to recruit tumor-supportive macrophages via the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis and to promote their polarization toward the M2 phenotype [153].

The Tomasson group undertook an ambitious approach to map the genetic determinants that underlie the propensity of C57KaLwRij mouse strain to develop spontaneous myeloma. Their hits included deletion of Samsn1 and deleterious point mutations in Tnfrsf22 and Tnfrsf23. Samsn1 loss promoted macrophage M2 polarization in a congenic model [154].

The Bogen group and collaborators implicated macrophages in CD4+-dependent myeloma immunosurveillance [155]. Th1 cells that recognize antigen presented by macrophages, in turn, activate the latter’s tumoricidal properties. This effect is likely mediated via CD40L-CD40 interactions. The importance of the CD40 pathway was also shown by our group [156, 157]. Indeed, CD40-activated macrophages exerted tumoricidal activity against myeloma cells in vivo in a T and NK cell–independent manner. The effect was promoted by loss of Tpl2 kinase, which we hypothesized to constitute an innate immune checkpoint.

Guttierez-Gonzalez et al. [158] used a combination of GM-CSF plus the MIF inhibitor 4-IPP to reprogram macrophages toward an M1 profile, which resulted in remarkable antimyeloma tumoricidal effects. Bergsagel and Chesi [159] demonstrated potent clinical activity of LCL161, an IAP antagonist that targets the cellular inhibitor of apoptosis proteins cIAP1 and -2 through enhancement of antimyeloma phagocytic activity and activation of macrophages and DCs. Robust in vivo antimyeloma activity of LCL161 was seen in a transgenic myeloma mouse model and in patients with relapsed-refractory myeloma, where the addition of cyclophosphamide resulted in a median progression-free-survival of 10 mo. Mechanistically, the effect was the result of tumor cell–autonomous type I IFN signaling and a strong inflammatory response. Thus, macrophages exert trophic roles in the niche but can be reprogrammed to kill tumor cells—the latter property may become particularly useful in tumors that have undergone immunoediting to escape antigen-specific adaptive immune surveillance.

Lastly, the concept of neutrophil polarization in the tumor niche has received scrutiny in the last few years [160–162]. Neutrophils have been postulated to display functional plasticity in crosstalk with the tumor microenvironment, mirroring principles that have been established for tumor-associated macrophages [118]. It will be essential to examine how neutrophil polarization and functions interact dynamically with other tumor-associated myeloid cells and ECM in myeloma progression.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

During myeloma evolution, infiltrating myeloid cells and stromal cells remodel ECM, which, in turn, regulates inflammation and immunity in the niche via generation of novel matrikines, spatial regulation of cytokine, and chemokine networks as well as receptor-mediated cellular signaling. This tightly regulated crosstalk harbors paramount therapeutic opportunity as we seek to control, and hopefully soon cure, myeloma through novel immunomodulatory agents and cellular therapies.

AUTHORSHIP

F.A. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. C.H., M.G.J., A.P., K.G., and B.N. reviewed, critiqued, and edited the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work in the authors’ laboratory is supported by the American Cancer Society, the UWCCC Trillium Fund for Multiple Myeloma Research, and the National Institutes of Health Grants P30-CA014520 and T32-HL007899.

Glossary

- ADAM

a-disintegrin-and-metalloproteinase

- ADAMTS

a-disintegrin-and-metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motif

- CR

complete response

- DAMP

damage-associated molecular pattern

- DC

dendritic cell

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- HS

heparan sulfate

- MDSC

myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- MGUS

monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- pDC

plasmacytoid dendritic cell

- PMN

polymorphonuclear

- SLRP

small leucine-rich proteoglycan

- TIMP

tissue-inhibitor of metalloproteinase

- VEGFR

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Palumbo A., Anderson K. (2011) Multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 1046–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgan G. J., Walker B. A., Davies F. E. (2012) The genetic architecture of multiple myeloma. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 335–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chesi M., Bergsagel P. L. (2011) Many multiple myelomas: making more of the molecular mayhem. Hematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program) 2011, 344–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuehl W. M., Bergsagel P. L. (2012) Molecular pathogenesis of multiple myeloma and its premalignant precursor. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 3456–3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abe M. (2011) Targeting the interplay between myeloma cells and the bone marrow microenvironment in myeloma. Int. J. Hematol. 94, 334–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitsiades C. S., McMillin D. W., Klippel S., Hideshima T., Chauhan D., Richardson P. G., Munshi N. C., Anderson K. C. (2007) The role of the bone marrow microenvironment in the pathophysiology of myeloma and its significance in the development of more effective therapies. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 21, 1007–1034, vii–viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribatti D., Nico B., Vacca A. (2006) Importance of the bone marrow microenvironment in inducing the angiogenic response in multiple myeloma. Oncogene 25, 4257–4266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roodman G. D. (2010) Targeting the bone microenvironment in multiple myeloma. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 28, 244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawano Y., Moschetta M., Manier S., Glavey S., Görgün G. T., Roccaro A. M., Anderson K. C., Ghobrial I. M. (2015) Targeting the bone marrow microenvironment in multiple myeloma. Immunol. Rev. 263, 160–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghobrial I. M. (2012) Myeloma as a model for the process of metastasis: implications for therapy. Blood 120, 20–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martins G., Calame K. (2008) Regulation and functions of Blimp-1 in T and B lymphocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 26, 133–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wehrli N., Legler D. F., Finke D., Toellner K. M., Loetscher P., Baggiolini M., MacLennan I. C., Acha-Orbea H. (2001) Changing responsiveness to chemokines allows medullary plasmablasts to leave lymph nodes. Eur. J. Immunol. 31, 609–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergsagel P. L., Kuehl W. M. (2001) Chromosome translocations in multiple myeloma. Oncogene 20, 5611–5622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasmussen T., Kuehl M., Lodahl M., Johnsen H. E., Dahl I. M. (2005) Possible roles for activating RAS mutations in the MGUS to MM transition and in the intramedullary to extramedullary transition in some plasma cell tumors. Blood 105, 317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasmussen T., Haaber J., Dahl I. M., Knudsen L. M., Kerndrup G. B., Lodahl M., Johnsen H. E., Kuehl M. (2010) Identification of translocation products but not K-RAS mutations in memory B cells from patients with multiple myeloma. Haematologica 95, 1730–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapman M. A., Lawrence M. S., Keats J. J., Cibulskis K., Sougnez C., Schinzel A. C., Harview C. L., Brunet J. P., Ahmann G. J., Adli M., Anderson K. C., Ardlie K. G., Auclair D., Baker A., Bergsagel P. L., Bernstein B. E., Drier Y., Fonseca R., Gabriel S. B., Hofmeister C. C., Jagannath S., Jakubowiak A. J., Krishnan A., Levy J., Liefeld T., Lonial S., Mahan S., Mfuko B., Monti S., Perkins L. M., Onofrio R., Pugh T. J., Rajkumar S. V., Ramos A. H., Siegel D. S., Sivachenko A., Stewart A. K., Trudel S., Vij R., Voet D., Winckler W., Zimmerman T., Carpten J., Trent J., Hahn W. C., Garraway L. A., Meyerson M., Lander E. S., Getz G., Golub T. R. (2011) Initial genome sequencing and analysis of multiple myeloma. Nature 471, 467–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lohr J. G., Stojanov P., Carter S. L., Cruz-Gordillo P., Lawrence M. S., Auclair D., Sougnez C., Knoechel B., Gould J., Saksena G., Cibulskis K., McKenna A., Chapman M. A., Straussman R., Levy J., Perkins L. M., Keats J. J., Schumacher S. E., Rosenberg M., Getz G., Golub T. R.; Multiple Myeloma Research Consortium (2014) Widespread genetic heterogeneity in multiple myeloma: implications for targeted therapy. Cancer Cell 25, 91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guillerey C., Nakamura K., Vuckovic S., Hill G. R., Smyth M. J. (2016) Immune responses in multiple myeloma: role of the natural immune surveillance and potential of immunotherapies. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 1569–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexandrov L. B., Nik-Zainal S., Wedge D. C., Aparicio S. A., Behjati S., Biankin A. V., Bignell G. R., Bolli N., Borg A., Børresen-Dale A. L., Boyault S., Burkhardt B., Butler A. P., Caldas C., Davies H. R., Desmedt C., Eils R., Eyfjörd J. E., Foekens J. A., Greaves M., Hosoda F., Hutter B., Ilicic T., Imbeaud S., Imielinski M., Jäger N., Jones D. T., Jones D., Knappskog S., Kool M., Lakhani S. R., López-Otín C., Martin S., Munshi N. C., Nakamura H., Northcott P. A., Pajic M., Papaemmanuil E., Paradiso A., Pearson J. V., Puente X. S., Raine K., Ramakrishna M., Richardson A. L., Richter J., Rosenstiel P., Schlesner M., Schumacher T. N., Span P. N., Teague J. W., Totoki Y., Tutt A. N., Valdés-Mas R., van Buuren M. M., van ’t Veer L., Vincent-Salomon A., Waddell N., Yates L. R., Zucman-Rossi J., Futreal P. A., McDermott U., Lichter P., Meyerson M., Grimmond S. M., Siebert R., Campo E., Shibata T., Pfister S. M., Campbell P. J., Stratton M. R.; Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative; ICGC Breast Cancer Consortium; ICGC MMML-Seq Consortium; ICGC PedBrain (2013) Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 500, 415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Usmani S. Z., Rodriguez-Otero P., Bhutani M., Mateos M. V., Miguel J. S. (2015) Defining and treating high-risk multiple myeloma. Leukemia 29, 2119–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta A., Place M., Goldstein S., Sarkar D., Zhou S., Potamousis K., Kim J., Flanagan C., Li Y., Newton M. A., Callander N. S., Hematti P., Bresnick E. H., Ma J., Asimakopoulos F., Schwartz D. C. (2015) Single-molecule analysis reveals widespread structural variation in multiple myeloma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 7689–7694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spranger S., Sivan A., Corrales L., Gajewski T. F. (2016) Tumor and host factors controlling antitumor immunity and efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Adv. Immunol. 130, 75–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koduru S., Wong E., Strowig T., Sundaram R., Zhang L., Strout M. P., Flavell R. A., Schatz D. G., Dhodapkar K. M., Dhodapkar M. V. (2012) Dendritic cell-mediated activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID)-dependent induction of genomic instability in human myeloma. Blood 119, 2302–2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karin M., Greten F. R. (2005) NF-kappaB: linking inflammation and immunity to cancer development and progression. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 749–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuehl W. M., Bergsagel P. L. (2002) Multiple myeloma: evolving genetic events and host interactions. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 175–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roodman G. D. (2009) Pathogenesis of myeloma bone disease. Leukemia 23, 435–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstock M., Ghobrial I. M. (2013) Extramedullary multiple myeloma. Leuk. Lymphoma 54, 1135–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Touzeau C., Moreau P. (2016) How I treat extramedullary myeloma. Blood 127, 971–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papanikolaou X., Repousis P., Tzenou T., Maltezas D., Kotsopoulou M., Megalakaki K., Angelopoulou M., Dimitrakoloulou E., Koulieris E., Bartzis V., Pangalis G., Panayotidis P., Kyrtsonis M.-C. (2013) Incidence, clinical features, laboratory findings and outcome of patients with multiple myeloma presenting with extramedullary relapse. Leuk. Lymphoma 54, 1459–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wirk B., Wingard J. R., Moreb J. S. (2013) Extramedullary disease in plasma cell myeloma: the iceberg phenomenon. Bone Marrow Transplant. 48, 10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asimakopoulos F., Kim J., Denu R. A., Hope C., Jensen J. L., Ollar S. J., Hebron E., Flanagan C., Callander N., Hematti P. (2013) Macrophages in multiple myeloma: emerging concepts and therapeutic implications. Leuk. Lymphoma 54, 2112–2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonnans C., Chou J., Werb Z. (2014) Remodelling the extracellular matrix in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 786–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hynes R. O., Naba A. (2012) Overview of the matrisome--an inventory of extracellular matrix constituents and functions. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a004903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang D., Lim S. Y. (2016) Influence of immune myeloid cells on the extracellular matrix during cancer metastasis. Cancer Microenviron. 9, 45–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khokha R., Murthy A., Weiss A. (2013) Metalloproteinases and their natural inhibitors in inflammation and immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 649–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slany A., Haudek-Prinz V., Meshcheryakova A., Bileck A., Lamm W., Zielinski C., Gerner C., Drach J. (2014) Extracellular matrix remodeling by bone marrow fibroblast-like cells correlates with disease progression in multiple myeloma. J. Proteome Res. 13, 844–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schaefer L. (2014) Complexity of danger: the diverse nature of damage-associated molecular patterns. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 35237–35245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaefer L., Iozzo R. V. (2012) Small leucine-rich proteoglycans, at the crossroad of cancer growth and inflammation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 22, 56–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Babelova A., Moreth K., Tsalastra-Greul W., Zeng-Brouwers J., Eickelberg O., Young M. F., Bruckner P., Pfeilschifter J., Schaefer R. M., Gröne H. J., Schaefer L. (2009) Biglycan, a danger signal that activates the NLRP3 inflammasome via Toll-like and P2X receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 24035–24048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merline R., Moreth K., Beckmann J., Nastase M. V., Zeng-Brouwers J., Tralhão J. G., Lemarchand P., Pfeilschifter J., Schaefer R. M., Iozzo R. V., Schaefer L. (2011) Signaling by the matrix proteoglycan decorin controls inflammation and cancer through PDCD4 and MicroRNA-21. Sci. Signal. 4, ra75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nemani N., Santo L., Eda H., Cirstea D., Mishima Y., Patel C., O’Donnell E., Yee A., Raje N. (2015) Role of decorin in multiple myeloma (MM) bone marrow microenvironment. J. Bone Miner. Res. 30, 465–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu F., Vij N., Roberts L., Lopez-Briones S., Joyce S., Chakravarti S. (2007) A novel role of the lumican core protein in bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced innate immune response. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 26409–26417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skliris A., Labropoulou V. T., Papachristou D. J., Aletras A., Karamanos N. K., Theocharis A. D. (2013) Cell-surface serglycin promotes adhesion of myeloma cells to collagen type I and affects the expression of matrix metalloproteinases. FEBS J. 280, 2342–2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Purushothaman A., Toole B. P. (2014) Serglycin proteoglycan is required for multiple myeloma cell adhesion, in vivo growth, and vascularization. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 5499–5509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCulloch D. R., Nelson C. M., Dixon L. J., Silver D. L., Wylie J. D., Lindner V., Sasaki T., Cooley M. A., Argraves W. S., Apte S. S. (2009) ADAMTS metalloproteases generate active versican fragments that regulate interdigital web regression. Dev. Cell 17, 687–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nandadasa S., Foulcer S., Apte S. S. (2014) The multiple, complex roles of versican and its proteolytic turnover by ADAMTS proteases during embryogenesis. Matrix Biol. 35, 34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Du W. W., Yang W., Yee A. J. (2013) Roles of versican in cancer biology--tumorigenesis, progression and metastasis. Histol. Histopathol. 28, 701–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ricciardelli C., Sakko A. J., Ween M. P., Russell D. L., Horsfall D. J. (2009) The biological role and regulation of versican levels in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 28, 233–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wight T. N., Kang I., Merrilees M. J. (2014) Versican and the control of inflammation. Matrix Biol. 35, 152–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wight T. N., Kinsella M. G., Evanko S. P., Potter-Perigo S., Merrilees M. J. (2014) Versican and the regulation of cell phenotype in disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1840, 2441–2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Z., Miao L., Wang L. (2012) Inflammation amplification by versican: the first mediator. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13, 6873–6882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Said N., Sanchez-Carbayo M., Smith S. C., Theodorescu D. (2012) RhoGDI2 suppresses lung metastasis in mice by reducing tumor versican expression and macrophage infiltration. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 1503–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim S., Karin M. (2011) Role of TLR2-dependent inflammation in metastatic progression. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1217, 191–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim S., Takahashi H., Lin W. W., Descargues P., Grivennikov S., Kim Y., Luo J. L., Karin M. (2009) Carcinoma-produced factors activate myeloid cells through TLR2 to stimulate metastasis. Nature 457, 102–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gao D., Joshi N., Choi H., Ryu S., Hahn M., Catena R., Sadik H., Argani P., Wagner P., Vahdat L. T., Port J. L., Stiles B., Sukumar S., Altorki N. K., Rafii S., Mittal V. (2012) Myeloid progenitor cells in the premetastatic lung promote metastases by inducing mesenchymal to epithelial transition. Cancer Res. 72, 1384–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang M., Diao J., Gu H., Khatri I., Zhao J., Cattral M. S. (2015) Toll-like receptor 2 activation promotes tumor dendritic cell dysfunction by regulating IL-6 and IL-10 receptor signaling. Cell Reports 13, 2851–2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gupta N., Khan R., Kumar R., Kumar L., Sharma A. (2015) Versican and its associated molecules: potential diagnostic markers for multiple myeloma. Clin. Chim. Acta 442, 119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hope C., Ollar S. J., Heninger E., Hebron E., Jensen J. L., Kim J., Maroulakou I., Miyamoto S., Leith C., Yang D. T., Callander N., Hematti P., Chesi M., Bergsagel P. L., Asimakopoulos F. (2014) TPL2 kinase regulates the inflammatory milieu of the myeloma niche. Blood 123, 3305–3315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hope C., Foulcer S., Jagodinsky J., Chen S. X., Jensen J. L., Patel S., Leith C., Maroulakou I., Callander N., Miyamoto S., Hematti P., Apte S. S., Asimakopoulos F. (2016) Immunoregulatory roles of versican proteolysis in the myeloma microenvironment. Blood 128, 680–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu Y. J., La Pierre D. P., Wu J., Yee A. J., Yang B. B. (2005) The interaction of versican with its binding partners. Cell Res. 15, 483–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmitt M. (2016) Versican vs versikine: tolerance vs attack. Blood 128, 612–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yeku O. O., Brentjens R. J. (2016) Armored CAR T-cells: utilizing cytokines and pro-inflammatory ligands to enhance CAR T-cell anti-tumour efficacy. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 44, 412–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Felix K., Gaida M. M. (2016) Neutrophil-derived proteases in the microenvironment of pancreatic cancer--active players in tumor progression. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 12, 302–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kessenbrock K., Plaks V., Werb Z. (2010) Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell 141, 52–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ardi V. C., Kupriyanova T. A., Deryugina E. I., Quigley J. P. (2007) Human neutrophils uniquely release TIMP-free MMP-9 to provide a potent catalytic stimulator of angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 20262–20267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kelly T., Børset M., Abe E., Gaddy-Kurten D., Sanderson R. D. (2000) Matrix metalloproteinases in multiple myeloma. Leuk. Lymphoma 37, 273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Van Valckenborgh E., Croucher P. I., De Raeve H., Carron C., De Leenheer E., Blacher S., Devy L., Noël A., De Bruyne E., Asosingh K., Van Riet I., Van Camp B., Vanderkerken K. (2004) Multifunctional role of matrix metalloproteinases in multiple myeloma: a study in the 5T2MM mouse model. Am. J. Pathol. 165, 869–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vacca A., Ribatti D., Presta M., Minischetti M., Iurlaro M., Ria R., Albini A., Bussolino F., Dammacco F. (1999) Bone marrow neovascularization, plasma cell angiogenic potential, and matrix metalloproteinase-2 secretion parallel progression of human multiple myeloma. Blood 93, 3064–3073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Urbaniak-Kujda D., Kapelko-Slowik K., Prajs I., Dybko J., Wolowiec D., Biernat M., Slowik M., Kuliczkowski K. (2016) Increased expression of metalloproteinase-2 and -9 (MMP-2, MMP-9), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 and -2 (TIMP-1, TIMP-2), and EMMPRIN (CD147) in multiple myeloma. Hematology 21, 26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zdzisińska B., Walter-Croneck A., Kandefer-Szerszeń M. (2008) Matrix metalloproteinases-1 and -2, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 production is abnormal in bone marrow stromal cells of multiple myeloma patients. Leuk. Res. 32, 1763–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barillé S., Akhoundi C., Collette M., Mellerin M. P., Rapp M. J., Harousseau J. L., Bataille R., Amiot M. (1997) Metalloproteinases in multiple myeloma: production of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), activation of proMMP-2, and induction of MMP-1 by myeloma cells. Blood 90, 1649–1655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barillé S., Bataille R., Rapp M. J., Harousseau J. L., Amiot M. (1999) Production of metalloproteinase-7 (matrilysin) by human myeloma cells and its potential involvement in metalloproteinase-2 activation. J. Immunol. 163, 5723–5728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Godefroy E., Gallois A., Idoyaga J., Merad M., Tung N., Monu N., Saenger Y., Fu Y., Ravindran R., Pulendran B., Jotereau F., Trombetta S., Bhardwaj N. (2014) Activation of Toll-like receptor-2 by endogenous matrix metalloproteinase-2 modulates dendritic-cell-mediated inflammatory responses. Cell Reports 9, 1856–1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dhodapkar M. V., Kelly T., Theus A., Athota A. B., Barlogie B., Sanderson R. D. (1997) Elevated levels of shed syndecan-1 correlate with tumour mass and decreased matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity in the serum of patients with multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 99, 368–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Van Valckenborgh E., Bakkus M., Munaut C., Noël A., St Pierre Y., Asosingh K., Van Riet I., Van Camp B., Vanderkerken K. (2002) Upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in murine 5T33 multiple myeloma cells by interaction with bone marrow endothelial cells. Int. J. Cancer 101, 512–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vande Broek I., Asosingh K., Allegaert V., Leleu X., Facon T., Vanderkerken K., Van Camp B., Van Riet I. (2004) Bone marrow endothelial cells increase the invasiveness of human multiple myeloma cells through upregulation of MMP-9: evidence for a role of hepatocyte growth factor. Leukemia 18, 976–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fu J., Li S., Feng R., Ma H., Sabeh F., Roodman G. D., Wang J., Robinson S., Guo X. E., Lund T., Normolle D., Mapara M. Y., Weiss S. J., Lentzsch S. (2016) Multiple myeloma-derived MMP-13 mediates osteoclast fusogenesis and osteolytic disease. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 1759–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bret C., Hose D., Reme T., Kassambara A., Seckinger A., Meissner T., Schved J. F., Kanouni T., Goldschmidt H., Klein B. (2011) Gene expression profile of ADAMs and ADAMTSs metalloproteinases in normal and malignant plasma cells and in the bone marrow environment. Exp. Hematol. 39, 546–557.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kern C. B., Wessels A., McGarity J., Dixon L. J., Alston E., Argraves W. S., Geeting D., Nelson C. M., Menick D. R., Apte S. S. (2010) Reduced versican cleavage due to Adamts9 haploinsufficiency is associated with cardiac and aortic anomalies. Matrix Biol. 29, 304–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rousseau S., Papoutsopoulou M., Symons A., Cook D., Lucocq J. M., Prescott A. R., O’Garra A., Ley S. C., Cohen P. (2008) TPL2-mediated activation of ERK1 and ERK2 regulates the processing of pre-TNF alpha in LPS-stimulated macrophages. J. Cell Sci. 121, 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hebron E., Hope C., Kim J., Jensen J. L., Flanagan C., Bhatia N., Maroulakou I., Mitsiades C., Miyamoto S., Callander N., Hematti P., Asimakopoulos F. (2013) MAP3K8 kinase regulates myeloma growth by cell-autonomous and non-autonomous mechanisms involving myeloma-associated monocytes/macrophages. Br. J. Haematol. 160, 779–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Terpos E., Dimopoulos M. A., Sezer O., Roodman D., Abildgaard N., Vescio R., Tosi P., Garcia-Sanz R., Davies F., Chanan-Khan A., Palumbo A., Sonneveld P., Drake M. T., Harousseau J. L., Anderson K. C., Durie B. G.; International Myeloma Working Group (2010) The use of biochemical markers of bone remodeling in multiple myeloma: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Leukemia 24, 1700–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Meyaard L. (2008) The inhibitory collagen receptor LAIR-1 (CD305). J. Leukoc. Biol. 83, 799–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Weathington N. M., van Houwelingen A. H., Noerager B. D., Jackson P. L., Kraneveld A. D., Galin F. S., Folkerts G., Nijkamp F. P., Blalock J. E. (2006) A novel peptide CXCR ligand derived from extracellular matrix degradation during airway inflammation. Nat. Med. 12, 317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Thomas A. H., Edelman E. R., Stultz C. M. (2007) Collagen fragments modulate innate immunity. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 232, 406–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen P., Cescon M., Zuccolotto G., Nobbio L., Colombelli C., Filaferro M., Vitale G., Feltri M. L., Bonaldo P. (2015) Collagen VI regulates peripheral nerve regeneration by modulating macrophage recruitment and polarization. Acta Neuropathol. 129, 97–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Franz S., Allenstein F., Kajahn J., Forstreuter I., Hintze V., Möller S., Simon J. C. (2013) Artificial extracellular matrices composed of collagen I and high-sulfated hyaluronan promote phenotypic and functional modulation of human pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages. Acta Biomater. 9, 5621–5629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Drakes M. L., Lu L., McKenna H. J., Thomson A. W. (1997) The influence of collagen, fibronectin, and laminin on the maturation of dendritic cell progenitors propagated from normal or Flt3-ligand-treated mouse liver. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 417, 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Franco C., Britto K., Wong E., Hou G., Zhu S. N., Chen M., Cybulsky M. I., Bendeck M. P. (2009) Discoidin domain receptor 1 on bone marrow-derived cells promotes macrophage accumulation during atherogenesis. Circ. Res. 105, 1141–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Machino-Ohtsuka T., Tajiri K., Kimura T., Sakai S., Sato A., Yoshida T., Hiroe M., Yasutomi Y., Aonuma K., Imanaka-Yoshida K. (2014) Tenascin-C aggravates autoimmune myocarditis via dendritic cell activation and Th17 cell differentiation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 3, e001052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kiyeko G. W., Hatterer E., Herren S., Di Ceglie I., van Lent P. L., Reith W., Kosco-Vilbois M., Ferlin W., Shang L. (2016) Spatiotemporal expression of endogenous TLR4 ligands leads to inflammation and bone erosion in mouse collagen-induced arthritis. Eur. J. Immunol. 46, 2629–2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kibler C., Schermutzki F., Waller H. D., Timpl R., Müller C. A., Klein G. (1998) Adhesive interactions of human multiple myeloma cell lines with different extracellular matrix molecules. Cell Adhes. Commun. 5, 307–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hoang B., Zhu L., Shi Y., Frost P., Yan H., Sharma S., Sharma S., Goodglick L., Dubinett S., Lichtenstein A. (2006) Oncogenic RAS mutations in myeloma cells selectively induce cox-2 expression, which participates in enhanced adhesion to fibronectin and chemoresistance. Blood 107, 4484–4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Turk N., Kusec R., Jaksic B., Turk Z. (2005) Humoral SPARC/osteonectin protein in plasma cell dyscrasias. Ann. Hematol. 84, 304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brekken R. A., Puolakkainen P., Graves D. C., Workman G., Lubkin S. R., Sage E. H. (2003) Enhanced growth of tumors in SPARC null mice is associated with changes in the ECM. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 487–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lin L., Yan F., Zhao D., Lv M., Liang X., Dai H., Qin X., Zhang Y., Hao J., Sun X., Yin Y., Huang X., Zhang J., Lu J., Ge Q. (2016) Reelin promotes the adhesion and drug resistance of multiple myeloma cells via integrin β1 signaling and STAT3. Oncotarget 7, 9844–9858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jiang H., Hegde S., Knolhoff B. L., Zhu Y., Herndon J. M., Meyer M. A., Nywening T. M., Hawkins W. G., Shapiro I. M., Weaver D. T., Pachter J. A., Wang-Gillam A., DeNardo D. G. (2016) Targeting focal adhesion kinase renders pancreatic cancers responsive to checkpoint immunotherapy. Nat. Med. 22, 851–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chanmee T., Ontong P., Itano N. (2016) Hyaluronan: a modulator of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 375, 20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Calabro A., Oken M. M., Hascall V. C., Masellis A. M. (2002) Characterization of hyaluronan synthase expression and hyaluronan synthesis in bone marrow mesenchymal progenitor cells: predominant expression of HAS1 mRNA and up-regulated hyaluronan synthesis in bone marrow cells derived from multiple myeloma patients. Blood 100, 2578–2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Taylor K. R., Yamasaki K., Radek K. A., Di Nardo A., Goodarzi H., Golenbock D., Beutler B., Gallo R. L. (2007) Recognition of hyaluronan released in sterile injury involves a unique receptor complex dependent on Toll-like receptor 4, CD44, and MD-2. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 18265–18275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Laudat A., Guechot J., Lecourbe K., Damade R., Palluel A. M. (2000) Hyaluronidase activity in serum of patients with monoclonal gammapathy. Clin. Chim. Acta 301, 159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ohwada C., Nakaseko C., Koizumi M., Takeuchi M., Ozawa S., Naito M., Tanaka H., Oda K., Cho R., Nishimura M., Saito Y. (2008) CD44 and hyaluronan engagement promotes dexamethasone resistance in human myeloma cells. Eur. J. Haematol. 80, 245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bjorklund C. C., Baladandayuthapani V., Lin H. Y., Jones R. J., Kuiatse I., Wang H., Yang J., Shah J. J., Thomas S. K., Wang M., Weber D. M., Orlowski R. Z. (2014) Evidence of a role for CD44 and cell adhesion in mediating resistance to lenalidomide in multiple myeloma: therapeutic implications. Leukemia 28, 373–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Maxwell C. A., Rasmussen E., Zhan F., Keats J. J., Adamia S., Strachan E., Crainie M., Walker R., Belch A. R., Pilarski L. M., Barlogie B., Shaughnessy J. Jr., Reiman T. (2004) RHAMM expression and isoform balance predict aggressive disease and poor survival in multiple myeloma. Blood 104, 1151–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sanderson R. D., Elkin M., Rapraeger A. C., Ilan N., Vlodavsky I. (2017) Heparanase regulation of cancer, autophagy and inflammation: new mechanisms and targets for therapy. FEBS J. 284, 42–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Termeer C. C., Hennies J., Voith U., Ahrens T., Weiss J. M., Prehm P., Simon J. C. (2000) Oligosaccharides of hyaluronan are potent activators of dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 165, 1863–1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Barash U., Cohen-Kaplan V., Dowek I., Sanderson R. D., Ilan N., Vlodavsky I. (2010) Proteoglycans in health and disease: new concepts for heparanase function in tumor progression and metastasis. FEBS J. 277, 3890–3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kelly T., Miao H. Q., Yang Y., Navarro E., Kussie P., Huang Y., MacLeod V., Casciano J., Joseph L., Zhan F., Zangari M., Barlogie B., Shaughnessy J., Sanderson R. D. (2003) High heparanase activity in multiple myeloma is associated with elevated microvessel density. Cancer Res. 63, 8749–8756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mahtouk K., Hose D., Raynaud P., Hundemer M., Jourdan M., Jourdan E., Pantesco V., Baudard M., De Vos J., Larroque M., Moehler T., Rossi J. F., Rème T., Goldschmidt H., Klein B. (2007) Heparanase influences expression and shedding of syndecan-1, and its expression by the bone marrow environment is a bad prognostic factor in multiple myeloma. Blood 109, 4914–4923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yang Y., MacLeod V., Dai Y., Khotskaya-Sample Y., Shriver Z., Venkataraman G., Sasisekharan R., Naggi A., Torri G., Casu B., Vlodavsky I., Suva L. J., Epstein J., Yaccoby S., Shaughnessy J. D. Jr., Barlogie B., Sanderson R. D. (2007) The syndecan-1 heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a viable target for myeloma therapy. Blood 110, 2041–2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Reijmers R. M., Spaargaren M., Pals S. T. (2013) Heparan sulfate proteoglycans in the control of B cell development and the pathogenesis of multiple myeloma. FEBS J. 280, 2180–2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jung O., Trapp-Stamborski V., Purushothaman A., Jin H., Wang H., Sanderson R. D., Rapraeger A. C. (2016) Heparanase-induced shedding of syndecan-1/CD138 in myeloma and endothelial cells activates VEGFR2 and an invasive phenotype: prevention by novel synstatins. Oncogenesis 5, e202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Beauvais D. M., Jung O., Yang Y., Sanderson R. D., Rapraeger A. C. (2016) Syndecan-1 (CD138) suppresses apoptosis in multiple myeloma by activating IGF1 receptor: prevention by synstatinIGF1R inhibits tumor growth. Cancer Res. 76, 4981–4993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Baniyash M. (2016) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as intruders and targets: clinical implications in cancer therapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 65, 857–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kumar V., Patel S., Tcyganov E., Gabrilovich D. I. (2016) The nature of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 37, 208–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Umansky V., Blattner C., Fleming V., Hu X., Gebhardt C., Altevogt P., Utikal J. (2016) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells and tumor escape from immune surveillance. [E-pub online ahead of print] Semin. Immunopathol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Marvel D., Gabrilovich D. I. (2015) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment: expect the unexpected. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 3356–3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gabrilovich D. I., Ostrand-Rosenberg S., Bronte V. (2012) Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 12, 253–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Brimnes M. K., Vangsted A. J., Knudsen L. M., Gimsing P., Gang A. O., Johnsen H. E., Svane I. M. (2010) Increased level of both CD4+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells and CD14+HLA-DR−/low myeloid-derived suppressor cells and decreased level of dendritic cells in patients with multiple myeloma. Scand. J. Immunol. 72, 540–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Görgün G. T., Whitehill G., Anderson J. L., Hideshima T., Maguire C., Laubach J., Raje N., Munshi N. C., Richardson P. G., Anderson K. C. (2013) Tumor-promoting immune-suppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the multiple myeloma microenvironment in humans. Blood 121, 2975–2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ramachandran I. R., Martner A., Pisklakova A., Condamine T., Chase T., Vogl T., Roth J., Gabrilovich D., Nefedova Y. (2013) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells regulate growth of multiple myeloma by inhibiting T cells in bone marrow. J. Immunol. 190, 3815–3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Favaloro J., Liyadipitiya T., Brown R., Yang S., Suen H., Woodland N., Nassif N., Hart D., Fromm P., Weatherburn C., Gibson J., Ho P. J., Joshua D. (2014) Myeloid derived suppressor cells are numerically, functionally and phenotypically different in patients with multiple myeloma. Leuk. Lymphoma 55, 2893–2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Van Valckenborgh E., Schouppe E., Movahedi K., De Bruyne E., Menu E., De Baetselier P., Vanderkerken K., Van Ginderachter J. A. (2012) Multiple myeloma induces the immunosuppressive capacity of distinct myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations in the bone marrow. Leukemia 26, 2424–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.De Veirman K., Van Ginderachter J. A., Lub S., De Beule N., Thielemans K., Bautmans I., Oyajobi B. O., De Bruyne E., Menu E., Lemaire M., Van Riet I., Vanderkerken K., Van Valckenborgh E. (2015) Multiple myeloma induces Mcl-1 expression and survival of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncotarget 6, 10532–10547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Giallongo C., Tibullo D., Parrinello N. L., La Cava P., Di Rosa M., Bramanti V., Di Raimondo C., Conticello C., Chiarenza A., Palumbo G. A., Avola R., Romano A., Di Raimondo F. (2016) Granulocyte-like myeloid derived suppressor cells (G-MDSC) are increased in multiple myeloma and are driven by dysfunctional mesenchymal stem cells (MSC). Oncotarget 7, 85764–85775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wang J., De Veirman K., De Beule N., Maes K., De Bruyne E., Van Valckenborgh E., Vanderkerken K., Menu E. (2015) The bone marrow microenvironment enhances multiple myeloma progression by exosome-mediated activation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncotarget 6, 43992–44004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Binsfeld M., Muller J., Lamour V., De Veirman K., De Raeve H., Bellahcène A., Van Valckenborgh E., Baron F., Beguin Y., Caers J., Heusschen R. (2016) Granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote angiogenesis in the context of multiple myeloma. Oncotarget 7, 37931–37943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ramachandran I. R., Condamine T., Lin C., Herlihy S. E., Garfall A., Vogl D. T., Gabrilovich D. I., Nefedova Y. (2016) Bone marrow PMN-MDSCs and neutrophils are functionally similar in protection of multiple myeloma from chemotherapy. Cancer Lett. 371, 117–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Görgün G., Samur M. K., Cowens K. B., Paula S., Bianchi G., Anderson J. E., White R. E., Singh A., Ohguchi H., Suzuki R., Kikuchi S., Harada T., Hideshima T., Tai Y. T., Laubach J. P., Raje N., Magrangeas F., Minvielle S., Avet-Loiseau H., Munshi N. C., Dorfman D. M., Richardson P. G., Anderson K. C. (2015) Lenalidomide enhances immune checkpoint blockade-induced immune response in multiple myeloma. Clin. Cancer Res. 21, 4607–4618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Krejcik J., Casneuf T., Nijhof I. S., Verbist B., Bald J., Plesner T., Syed K., Liu K., van de Donk N. W., Weiss B. M., Ahmadi T., Lokhorst H. M., Mutis T., Sasser A. K. (2016) Daratumumab depletes CD38+ immune regulatory cells, promotes T-cell expansion, and skews T-cell repertoire in multiple myeloma. Blood 128, 384–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hoyos V., Borrello I. (2016) The immunotherapy era of myeloma: monoclonal antibodies, vaccines, and adoptive T-cell therapies. Blood 128, 1679–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Noonan K. A., Ghosh N., Rudraraju L., Bui M., Borrello I. (2014) Targeting immune suppression with PDE5 inhibition in end-stage multiple myeloma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2, 725–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Califano J. A., Khan Z., Noonan K. A., Rudraraju L., Zhang Z., Wang H., Goodman S., Gourin C. G., Ha P. K., Fakhry C., Saunders J., Levine M., Tang M., Neuner G., Richmon J. D., Blanco R., Agrawal N., Koch W. M., Marur S., Weed D. T., Serafini P., Borrello I. (2015) Tadalafil augments tumor specific immunity in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 21, 30–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Brown R. D., Pope B., Murray A., Esdale W., Sze D. M., Gibson J., Ho P. J., Hart D., Joshua D. (2001) Dendritic cells from patients with myeloma are numerically normal but functionally defective as they fail to up-regulate CD80 (B7-1) expression after huCD40LT stimulation because of inhibition by transforming growth factor-beta1 and interleukin-10. Blood 98, 2992–2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ratta M., Fagnoni F., Curti A., Vescovini R., Sansoni P., Oliviero B., Fogli M., Ferri E., Della Cuna G. R., Tura S., Baccarani M., Lemoli R. M. (2002) Dendritic cells are functionally defective in multiple myeloma: the role of interleukin-6. Blood 100, 230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Yang D. H., Park J. S., Jin C. J., Kang H. K., Nam J. H., Rhee J. H., Kim Y. K., Chung S. Y., Choi S. J., Kim H. J., Chung I. J., Lee J. J. (2009) The dysfunction and abnormal signaling pathway of dendritic cells loaded by tumor antigen can be overcome by neutralizing VEGF in multiple myeloma. Leuk. Res. 33, 665–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Leone P., Berardi S., Frassanito M. A., Ria R., De Re V., Cicco S., Battaglia S., Ditonno P., Dammacco F., Vacca A., Racanelli V. (2015) Dendritic cells accumulate in the bone marrow of myeloma patients where they protect tumor plasma cells from CD8+ T-cell killing. Blood 126, 1443–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Tucci M., Ciavarella S., Strippoli S., Brunetti O., Dammacco F., Silvestris F. (2011) Immature dendritic cells from patients with multiple myeloma are prone to osteoclast differentiation in vitro. Exp. Hematol. 39, 773–783.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Wang S., Yang J., Qian J., Wezeman M., Kwak L. W., Yi Q. (2006) Tumor evasion of the immune system: inhibiting p38 MAPK signaling restores the function of dendritic cells in multiple myeloma. Blood 107, 2432–2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Lu Y., Zhang M., Wang S., Hong B., Wang Z., Li H., Zheng Y., Yang J., Davis R. E., Qian J., Hou J., Yi Q. (2014) p38 MAPK-inhibited dendritic cells induce superior antitumour immune responses and overcome regulatory T-cell-mediated immunosuppression. Nat. Commun. 5, 4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Spisek R., Charalambous A., Mazumder A., Vesole D. H., Jagannath S., Dhodapkar M. V. (2007) Bortezomib enhances dendritic cell (DC)-mediated induction of immunity to human myeloma via exposure of cell surface heat shock protein 90 on dying tumor cells: therapeutic implications. Blood 109, 4839–4845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Straube C., Wehner R., Wendisch M., Bornhäuser M., Bachmann M., Rieber E. P., Schmitz M. (2007) Bortezomib significantly impairs the immunostimulatory capacity of human myeloid blood dendritic cells. Leukemia 21, 1464–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.De Keersmaecker B., Fostier K., Corthals J., Wilgenhof S., Heirman C., Aerts J. L., Thielemans K., Schots R. (2014) Immunomodulatory drugs improve the immune environment for dendritic cell-based immunotherapy in multiple myeloma patients after autologous stem cell transplantation. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 63, 1023–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Luptakova K., Rosenblatt J., Glotzbecker B., Mills H., Stroopinsky D., Kufe T., Vasir B., Arnason J., Tzachanis D., Zwicker J. I., Joyce R. M., Levine J. D., Anderson K. C., Kufe D., Avigan D. (2013) Lenalidomide enhances anti-myeloma cellular immunity. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 62, 39–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Nguyen-Pham T. N., Jung S. H., Vo M. C., Thanh-Tran H. T., Lee Y. K., Lee H. J., Choi N. R., Hoang M. D., Kim H. J., Lee J. J. (2015) Lenalidomide synergistically enhances the effect of dendritic cell vaccination in a model of murine multiple myeloma. J. Immunother. 38, 330–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Chauhan D., Singh A. V., Brahmandam M., Carrasco R., Bandi M., Hideshima T., Bianchi G., Podar K., Tai Y. T., Mitsiades C., Raje N., Jaye D. L., Kumar S. K., Richardson P., Munshi N., Anderson K. C. (2009) Functional interaction of plasmacytoid dendritic cells with multiple myeloma cells: a therapeutic target. Cancer Cell 16, 309–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Vasir B., Borges V., Wu Z., Grosman D., Rosenblatt J., Irie M., Anderson K., Kufe D., Avigan D. (2005) Fusion of dendritic cells with multiple myeloma cells results in maturation and enhanced antigen presentation. Br. J. Haematol. 129, 687–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Rosenblatt J., Avivi I., Vasir B., Uhl L., Munshi N. C., Katz T., Dey B. R., Somaiya P., Mills H., Campigotto F., Weller E., Joyce R., Levine J. D., Tzachanis D., Richardson P., Laubach J., Raje N., Boussiotis V., Yuan Y. E., Bisharat L., Held V., Rowe J., Anderson K., Kufe D., Avigan D. (2013) Vaccination with dendritic cell/tumor fusions following autologous stem cell transplant induces immunologic and clinical responses in multiple myeloma patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 3640–3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Zheng Y., Cai Z., Wang S., Zhang X., Qian J., Hong S., Li H., Wang M., Yang J., Yi Q. (2009) Macrophages are an abundant component of myeloma microenvironment and protect myeloma cells from chemotherapy drug-induced apoptosis. Blood 114, 3625–3628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Ribatti D., Moschetta M., Vacca A. (2014) Macrophages in multiple myeloma. Immunol. Lett. 161, 241–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Panchabhai S., Kelemen K., Ahmann G., Sebastian S., Mantei J., Fonseca R. (2016) Tumor-associated macrophages and extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer in prognosis of multiple myeloma. Leukemia 30, 951–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]