Abstract

Objective

Using a community adolescent sample, we aimed to (a) empirically-derive eating disorder (ED) symptom groups, (b) examine the longitudinal stability of those groups over 10 years, and (c) identify risk factors associated with ED group stability and transition through young adulthood.

Method

Young people (N=2,287) from the Project EAT cohort participated at baseline (1998–1999) and at 10-year follow-up (2008–2009). Participants completed anthropometric measures at baseline and self-report surveys on disordered eating symptoms and risk factors at both time points. Latent transition modeling was used to test the first two aims and multinomial logistic regression was used for the third aim.

Results

Three groups emerged and were labeled as: (a) asymptomatic, (b) dieting, (c) disordered eating (e.g., binge eating, compensatory behaviors). Stability of group membership over 10 years was highest for those in the asymptomatic group, while those in the dieting group showed equal likelihood of transitioning to any group. There was a 75% chance that those in the disordered eating group would continue to belong to a symptomatic group 10 years later. We found that these transitions could be predicted by baseline risk factors. For example, adolescents with one standard deviation higher depressive symptoms than their peers had 53% higher odds (OR = 1.53, 95% CI 1.09–2.16) of transitioning from the asymptomatic group to the disordered eating group.

Discussion

Transition among ED groups is relatively common during adolescence and early adulthood. By targeting risk factors such as self-esteem and familial factors in early adolescence, prevention efforts may be improved.

Eating disorder (ED) symptoms often begin in adolescence with prevalence increasing over development. For example, rates of binge eating in adolescent girls increase 14% to 25% from mid to late adolescence (1–4), with the peak age of ED onset between 16 to 20 years old (5). Although engaging in early disordered eating is predictive of engaging in the same behaviors years later (6), there is evidence that individuals engaging in such behaviors may (a) transition to different forms of disordered eating (e.g., binge eating to restricting) or (b) transition to be asymptomatic over time (e.g., 7–9). However, to date, the majority of stability and transition studies in community samples have examined ED symptoms (e.g., 10) or pre-determined ED diagnostic groups (e.g., 8,11). Thus, little is known about how ED behaviors and symptoms empirically group together in early adolescence and how individuals shift among the groups over time. In particular, few studies have investigated the longer-term stability and transition of ED symptom groups from adolescence to adulthood and the associated risk factors. This is important because the heterogeneity of ED symptoms and behaviors in community samples cannot be captured by diagnostic groups as at-risk individuals are typically missed. Furthermore, empirical classifications tend to perform better than single symptoms or even diagnostic categories (12). Thus, it is critical to identify representative, empirically-derived ED groups and to examine how and why individuals transition between groups from adolescence to adulthood. This would have important implications for identifying at-risk teens and improving prevention and intervention efforts for certain groups of individuals.

Few studies have investigated the longitudinal stability and transition of empirically-derived ED symptom groups in community samples of adolescents (13,14). Some studies have used college-aged individuals (e.g., 15,16) and have thus missed out on the peak time of symptom onset and transition. One study by Kansi and colleagues (13) found evidence of both stability and transition in adolescents. The authors followed 623 Norwegian girls aged 13–14 for seven years and focused on stability of groups over time. They empirically identified eight clusters: (a) a mixed symptoms group, (b) a mild bulimic and dieting group, (c) a pronounced bulimic and dieting group, (d) a restrictive group, (e) a dieting-only group, (f) a mild bulimic symptom group, and (g) two asymptomatic groups. Most groups were stable over time, though some girls in the mild bulimic group, the pronounced bulimic group, and the mixed symptoms group tended to change membership over time. In terms of associated risk factors, they did not find support for their hypothesis that low self-esteem and high unstable self-perceptions (e.g., unstable identity) were risk factors for later disordered eating (13).

Another study with a British community sample empirically identified three ED groups at age 14: (a) an asymptomatic group, (b) an overweight group who endorsed overeating and binge eating as well as weight-control behaviors, and (c) a group that resembled bulimia nervosa (BN) with normal weight, and high probability of engaging in weight control behaviors and binge eating (14). They found that most girls in the symptomatic groups at age 14 stayed in a symptomatic group at ages 16 and 18, though transitioned between them, and that fewer girls transitioned to the asymptomatic group from the BN group by age 18. Overall, the authors concluded that adolescence is a transitory time with ED groups showing little stability over four years.

These studies have advanced our understanding of how ED behaviors group together and how adolescents may transition between them over a period of four and seven years (13,14); however, there were two primary limitations of those studies. First, the two studies we identified that examined transitions over time using empirical classifications (13,14) did not capture the full transition into adulthood. That is, we do not know how individuals would transition between groups from adolescence to independent adulthood (e.g., the age after which individuals are typically out of college). Second, these studies did not examine or identify any relevant risk factors. In order to expand on this literature and address these limitations and those mentioned in the first paragraph of the introduction, we aimed to (a) use advanced statistical modeling, latent transition analysis (LTA), to empirically identify groups of ED symptoms and examine the longitudinal stability of the identified groups during a 10-year critical developmental time period from adolescence to adulthood in a large, non-clinical sample; and (b) identify risk factors associated with group transition. Based on ED risk and maintenance literature, we examined the following risk factors: (a) weight risk factors, such as body mass index (BMI), weighing oneself often, and body dissatisfaction (17–20); (b) psychological risk factors, such as depressive symptoms, suicidality, substance use, and low self-esteem (1,9–11,17,18,21,22); and (c) socio-environmental risk factors, such as low parental support, infrequent family meals, and being teased about one’s weight (17,23,24).

Method

Sample

Project EAT (Eating and Activity in Teens and Young Adults) is a longitudinal study of eating-related, anthropometric and psychosocial factors among young people. Participants were male and female middle and high school students in and around Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minnesota assessed in early/middle adolescence (EAT-I; age 11–18 years) from 1998–1999 and 10-years later (EAT-III; age 21–29) in early/middle young adulthood. Middle and high school are obligatory in the United States and thus this sample represents a community-based population. Of the original 4,746 participants at EAT-I, 1,304 (27.5%) participants were lost to follow-up for various reasons, primarily due to missing contact information (n=411) or lack of address at follow-up (n=712). Of the 3,422 surveys sent out, 2,287 participants completed EAT-III, 10 years later. Thus, the sample in the current study is n=2,287. However, to account for loss at follow-up, inverse probability weights were applied to the sample in each model so that inferences could be drawn from the original sample of 4,746 adolescents.1 All study protocols were approved by the University of Minnesota’s Institutional Review Board.

Survey Measures2

ED symptom indicators

To replicate and be consistent with prior Project EAT studies (8,25) and to capture all relevant ED symptoms, the following variables were selected as the indicators of the latent groups. Importantly, these items have previously been mapped onto DSM-IV (26) diagnostic criteria for AN, BN, and BED (8,25). Low weight status was based on Body Mass Index (BMI), which was calculated using measured height and weight at EAT-I and self-reported height and weight at EAT-III (test-retest: r = 0.99). Self-reported and measured BMI were highly correlated (r = 0.86). Respondents were categorized by age and gender specific BMI z-score using cut-points based on Must and colleagues (27) and low weight status was scored as being below the 15th percentile of BMI z-score (25). For trying to lose weight, participants responded yes or no to the item “Are you currently trying to lose weight?” (test-retest EAT-I: r = 0.59; test-retest EAT-III: proportion concordant = 0.92). Fear of weight gain was assessed as answering, “strongly agree,” to the statement, “I am worried about gaining weight” (test-retest EAT-I: r = 0.72; test-retest EAT-III: r = 0.63). Body image distortion (25) was determined by two indicators: BMI and responses to one of two items. Normal weight or slightly underweight respondents between the 15th and 85th percentiles of BMI (i.e., between 18.5 and 25 kg/m2) for their age and gender were classified as having body image distortion if they responded “somewhat overweight” or “very overweight” to the following item: “At this time, do you feel that you are: very underweight, somewhat underweight, about the right weight, somewhat overweight, or very overweight?” (test-retest EAT-I: r = 0.66, test-retest EAT-III: r = 0.83). For low weight participants below the 15th percentile of BMI, (roughly equivalent to or below 18.5 kg/m2), if their response to the item assessing ideal weight, “At what weight do you think you would look best?” was less than their current weight, then they were classified as having body image distortion (test-retest EAT-I: r = 0.24, test-retest EAT-III: r = 0.97). Participants were classified as having binge eating with loss of control if they answered “yes” to both of the questions, “In the past year, have you ever eaten so much food in a short period of time that you would be embarrassed if others saw you?” (test-retest EAT-I: kappa = 0.64, test-retest EAT-III: proportion concordant = 0.92) and, “During the times when you ate this way did you feel you couldn’t stop eating or control what or how much you were eating?” (test-retest EAT-I: kappa = 0.23, test-retest EAT-III: proportion concordant = 0.84). Frequency of binge eating was assessed by asking participants who endorsed binge eating with loss of control, “How often, on average, did you have times when you ate this way?” (test-retest EAT-I: r =0.83, test-retest EAT-III: r = 0.47). Those who answered either “a few times a week” or “nearly every day” to this question were classified as binge eating frequently. Distress about binge eating was assessed by asking respondents who endorsed binge eating, “In general, how upset were you by overeating?” (test-retest EAT-I: r = 0.77, test-retest EAT-III: r = 0.84). Those who answered “some” or “a lot” were classified as having distress about bingeing. Finally, participants who endorsed one or more of the following were classified as engaging in compensatory behaviors: (a) purging (self-induced vomiting) in order to lose weight or keep from gaining weight during the past year (test-retest EAT-I: kappa = 0.58, test-retest EAT-III: proportion concordant = 0.98), or (b) laxative use in order to lose weight or keep from gaining weight during the past year (test-retest EAT-I: kappa = 0.29, test-retest EAT-III: proportion concordant = 0.98).

Predictor Variables at EAT-I of Transitions between ED Symptom Groups3

Weight-related risk factors

BMI was calculated from anthropometric measures of height and weight at EAT-I. Frequency of self-weighing was measured on four-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 4 = Strongly agree) to the item, “How strongly do you agree with the statement ‘I weigh myself often’” (test-retest: r = 0.70). Body satisfaction was measured on a five-point Likert scale to items assessing how satisfied participants were with 10 parts of their body (e.g., hips, height, stomach, etc.). Score was the sum of these 10 items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92, scale ranges from 10 to 50) with higher scores representing more body satisfaction.

Psychological risk factors

Depressive symptoms were measured as the sum of six items from the Kandel and Davies (28) Depressive Mood Scale. Items were scored on a three-point Likert scale. Higher scores represent greater depressive symptoms (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82). Self-esteem was assessed by six items from the Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale (29). Items were scored on a four-point Likert scale. Higher scores represent greater self-esteem (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74). For substance use, respondents were asked how often during the past 12 months they had used cigarettes, beer, wine or hard liquor or marijuana (test-retest: cigarettes r = 0.78, alcohol r = 0.68, marijuana r = 0.72). If the respondent reported using any substance “a few times” or more frequently, they were classified as having used a substance. Suicidal ideation was measured as a “yes” response to the question, “Have you ever thought about killing yourself?” (test-retest: r = 0.78). Lastly, suicide attempt was measured as a “yes” response to the question, “Have you ever tried to kill yourself?” (test-retest: r = 0.79).

Socio-environmental risk factors

Weight teasing by peers was assessed categorically (yes/no) with the question, “Have you ever been teased or made fun of by other kids because of your weight?” (test-retest: kappa = 0.59). Weight teasing by family was assessed categorically (yes/no) with the question, “Have you ever been teased or made fun of by family members because of your weight?” (test-retest: kappa = 0.78). Family communication/caring (30) was measured using the mean of responses to four items scored on a five-point Likert scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.68), with lower scores indicating lower family communication/caring. The following questions were asked for both mother and father: (a) “How much do you feel you can talk to your mother/father about your problems?” (b) “How much do you feel your mother/father cares about you?” Family meal frequency (31) was measured with the question, “During the past seven days, how many times did all, or most, of your family living in your house eat a meal together?” The six responses, which ranged from never to more than seven times, were converted to a continuous scale (test-retest: r = 0.73).

Demographic variables

Age, gender, race, and household socioeconomic status (SES) were self-reported and used as covariates in the current study (See Table I). Race was categorized into white and non-white, while SES (based primarily on parent education level) was classified as low, middle and high (32).

Table I.

Baseline Demographics for Sample Followed to EAT-III (n = 2287)

| Sex | Percent (n) |

|---|---|

| Male | 45.04% (1030) |

| Female | 54.96% (1257) |

| Race | |

| White | 48.4% (1458) |

| Black or African American | 18.6% (212) |

| Hispanic | 5.9% (89) |

| Asian | 19.6% (373) |

| Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0.49% (8) |

| Native American | 3.3% (65) |

| Mixed | 3.8% (60) |

| SES | |

| 1 (Low) | 11.83% (264) |

| 2 (Lower Middle) | 16.00% (357) |

| 3 (Middle) | 25.77% (575) |

| 4 (Upper Middle) | 28.73% (641) |

| 5 (High) | 17.66% (394) |

| Grade Level at Baseline | |

| 7th | 24.59% (559) |

| 8th | 5.19% (118) |

| 9th | 0.40% (9) |

| 10th | 56.93% (1294) |

| 11th | 9.41% (214) |

| 12th | 3.48% (79) |

NOTE: Percents have been weighted by non-response propensity to reflect the original EAT 1 sample population. N’s are unweighted.

Data Analysis

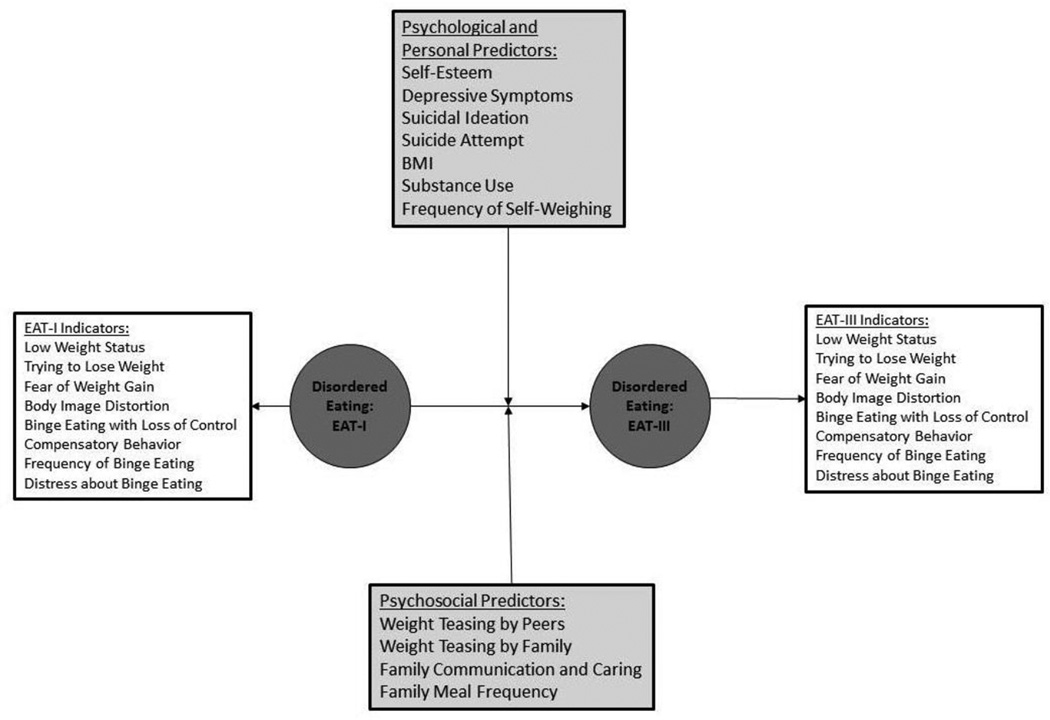

Latent transition analysis (LTA; 33) was used to: (a) identify ED symptom groups underlying eight symptom indicators at EAT-I and EAT-III and (b) estimate transition probabilities between those groups. Figure I outlines the LTA model. Because the number of latent groups underlying the symptoms in this sample was initially unknown, models with two to six groups at each time point were fit to determine the best number of symptom groups in the sample. Relative model fit statistics (Bayesian Information Criteria; BIC and adjusted BIC; aBIC) as well as parsimony and interpretability of the model were used to determine the number of groups. For these exploratory analyses, no constraints were placed to force the item-response probabilities defining the groups to be the same across time, allowing for the possibility of different symptom groups to emerge. Because the item-response probabilities were found to be very similar across time, a final LTA was fit constraining them to be the same. Residual covariances of the indicators within classes were examined. Because of multiple comparisons, residual covariances between indicators were freed in the final model if the covariances were significant at p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

This figure shows the model tested in the LTA. Indicator variables that created the groups are represented by the white boxes and predictor variables that predicted group transition are represented by the gray boxes. Tested Latent Transition Model of Eating Disorder Symptoms

When the best fitting LTA model was identified, we then modeled predictors of the transitions from one ED symptom group at EAT-I to a different symptom group at EAT-III. Multinomial logistic regression was used to test the association of EAT-I predictor variables with transitions between ED symptom groups. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the transitions are reported for all significant predictors. All models were adjusted for age, race, gender and socioeconomic status. Additional models were run to determine if the transition probabilities of the effect of the predictors differed by gender. However, due to small sample sizes in some latent groups, the estimates predictor effects were unreliable, especially for boys, so results are only presented for the main effect of gender. Analyses were done using MPlus7.4.

Results

Number of Latent Groups

The LTA with three groups at each time point showed best fit to the data (Table II) and demonstrated interpretable differences between the groups. Specifically, the three groups that emerged from the LTA were labeled as: (a) asymptomatic, characterized by the low probabilities of endorsing any symptoms; (b) dieting, characterized by high probabilities of endorsing “trying to lose weight” with low probabilities of any overt ED behaviors; and (c) disordered eating, characterized by high probabilities of most ED symptoms, including binge eating and compensatory behaviors. Table III lists the probabilities of responding “yes” to the indicator variables for each group.

Table II.

Goodness of Fit (BIC) for LTA Using Different Numbers of Groups

| Number of Classes* | BIC** | aBIC** |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 23066.86 | 23006.5 |

| 3 | 21845.33 | 21743.66 |

| 4 | 22002.96 | 21751.96 |

| 5 | 22365.07 | 21907.56 |

Unconditional LTAs were run specifying 2 to 5 latent groups

The lowest BIC and aBIC represent the best fit with 3 groups

Table III.

Response Percents to Indicator Items by Group at Each Time Point

| Asymptomatic Latent Group |

Dieting Latent Group |

Disordered Eating Latent Group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group Prevalence at EAT-I: % (n)* |

63% (1441) | 27% (617) | 10% (229) | ||

| Group Prevalence at EAT-III: % (n)* |

48% (1098) | 39% (892) | 13% (297) | ||

| Marginal Probability of Responding ‘Yes’ at EAT-I |

Marginal Probability of Responding ‘Yes’ at EAT-III |

LCA Item Response Probability |

LCA Item Response Probability |

LCA Item Response Probability |

|

| Low Weight Status | 4% | 6% | 8% | 1% | 1% |

| Trying to Lose Weight | 32% | 47% | 5% | 86%** | 75%** |

| Fear of Weight Gain | 21% | 30% | 4% | 51%** | 65%** |

| Body Image Distortion | 16% | 24% | 6% | 35% | 38% |

| Binge Eating with Loss of Control | 7% | 12% | 1% | 0% | 81%** |

| Compensatory Behavior | 19% | 10% | 1% | 7% | 18% |

| Frequency of Binge Eating | 3% | 4% | 0% | 0% | 37% |

| Distress about Binge Eating | 8% | 13% | 1% | 3% | 81%** |

Note. LCA assigns probability of group membership to each individual, so ns are estimated and not exact.

Item response probabilities above 50% are highlighted to show items that are strongly endorsed in each class.

Group Stability and Transition

The probability of transitioning between groups is shown in Table IV. Individuals who belonged to the asymptomatic group and the dieting group at EAT-I were most likely to remain in the same groups 10 years later (62–64% probability for both groups). For those in the dieting group at EAT-I, there was about equal likelihood (19% probability) of worsening symptoms and transitioning to the disordered eating group as there was improving and transitioning to the asymptomatic group (18% probability) 10 years later. Individuals in the disordered eating group at EAT-I, however, seemed to have somewhat similar likelihoods of belonging to a symptomatic group at EAT-III (e.g., the probability of staying in the disordered eating group was 35% and the probability of transitioning to the dieting group was 39%), with a slightly lower likelihood of transition to the asymptomatic group (26%).

Table IV.

Probabilities of Transitioning between Groups over a Ten-Year Period (from EAT-I to EAT-III)*

| EAT-III | ||||

| Asymptomatic | Dieting | Disordered Eating |

||

| EAT-I | Asymptomatic: % (n)**1441 | 64% (922) | 30% (432) | 6% (86) |

| Dieting: % (n)**617 | 18% (111) | 62% (383) | 19% (117) | |

| Disordered Eating: % (n)**229 |

26% (60) | 39% (89) | 35% (80) | |

Note. Percents may not add to 100 due to rounding

LCA assigns probability of group membership to each individual, so ns are estimated and not exact.

Predictors of the Transitions between Groups

Four EAT-I variables significantly predicted at least one of the possible transitions between latent groups from EAT-I to EAT-III. Three psychological predictors [self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and substance use] significantly predicted at least one transition (see Table V for odds ratios). Adolescents with one standard deviation higher self-esteem than their peers had a 37% lower odds (OR= 0.63, 95% CI 0.44–0.91) of transitioning from the asymptomatic group to the disordered eating group. Those with one standard deviation higher depressive symptoms than their peers had a 57% higher odds (OR = 1.57, 95% CI 1.08–2.27) of transitioning from the asymptomatic group to the disordered eating group and a 44% lower odds (OR=0.56, 95% CI 0.35–0.89) of transitioning from the disordered eating group to the dieting group. Adolescents who endorsed substance use at EAT-I had a 36% greater odds (OR = 1.36, 95% CI 1.05–1.77) of transitioning from the asymptomatic group to the disordered eating group than a participant who did not endorse substance use. One socio-environmental predictor [family communication/caring] significantly predicted at least one transition. While a one standard deviation higher family communication/caring than peers was associated with a 34% lower odds (OR =0.66, 95% CI 0.50–0.87) of transitioning from the asymptomatic group to the disordered eating group, it was also associated with a 41% lower odds (OR = 0.59, 95% CI 0.39–0.88) of transitioning from the dieting group to the asymptomatic group. However, this is a less severe transition with a relatively low prevalence (18%). Family weight teasing approached statistical significance for the transition from asymptomatic to disordered eating. Adolescents with one standard deviation higher family weight teasing than their peers had a 38% higher odds (OR = 1.38, 95% CI 1.00–1.89) of transitioning from the asymptomatic group to the disordered eating group. BMI, frequency of self-weighing, body dissatisfaction, suicide ideation, suicide attempt, family meal frequency, and weight teasing by peers were not significantly associated with any of the transitions between latent groups.

Table V.

Odds Ratios* [95% CI] for Significant Associations between Risk Factors and Transition

| BMI** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Frequency of Self- Weighing |

||||

| EAT-III | ||||

| EAT-I | Asymptomatic | Dieting | Disordered Eating | |

| Asymptomatic | 1 [Ref] | 0.94 [0.77 to 1.15] | 1.04 [0.78 to 1.39] | |

| Dieters | 1.06 [0.61 to 1.82] | 1 [Ref] | 1.14 [0.88 to 1.48] | |

| Disordered Eating |

1.53 [0.94 to 2.47] | 1 [0.69 to 1.45] | 1 [Ref] | |

| Body Satisfaction | ||||

| EAT-III | ||||

| EAT-I | Asymptomatic | Dieting | Disordered Eating | |

| Asymptomatic | 1 [Ref] | 1.04 [0.82 to 1.31] | 0.9 [0.65 to 1.27] | |

| Dieters | 1.11 [0.49 to 2.51] | 1 [Ref] | 0.85 [0.59 to 1.23] | |

| Disordered Eating |

1.84 [0.41 to 8.26] | 1.31 [0.7 to 2.44] | 1 [Ref] | |

|

Depressive Symptoms |

||||

| EAT-III | ||||

| EAT-I | Asymptomatic | Dieting | Disordered Eating | |

| Asymptomatic | 1 [Ref] | 1.03 [0.83 to 1.27] | 1.57 [1.08 to 2.27]*** |

|

| Dieters | 1.05 [0.71 to 1.55] | 1 [Ref] | 1.13 [0.84 to 1.53] | |

| Disordered Eating |

0.63 [0.35 to 1.11] | 0.56 [0.35 to 0.89]*** |

1 [Ref] | |

| Self Esteem | ||||

| EAT-III | ||||

| EAT-I | Asymptomatic | Dieting | Disordered Eating | |

| Asymptomatic | 1 [Ref] | 1.21 [0.98 to 1.49] | 0.63 [0.44 to 0.91]*** |

|

| Dieters | 0.9 [0.57 to 1.42] | 1 [Ref] | 1.06 [0.73 to 1.54] | |

| Disordered Eating |

1.38 [0.66 to 2.9] | 1.51 [0.94 to 2.41] | 1 [Ref] | |

| Substance Use | ||||

| EAT-III | ||||

| EAT-I | Asymptomatic | Dieting | Disordered Eating | |

| Asymptomatic | 1 [Ref] | 0.84 [0.7 to 1.02] | 1.36 [1.05 to 1.77]*** |

|

| Dieters | 0.7 [0.47 to 1.04] | 1 [Ref] | 0.79 [0.58 to 1.06] | |

| Disordered Eating |

0.79 [0.46 to 1.36] | 0.85 [0.56 to 1.3] | 1 [Ref] | |

| Suicidal Ideation | ||||

| EAT-III | ||||

| EAT-I | Asymptomatic | Dieting | Disordered Eating | |

| Asymptomatic | 1 [Ref] | 1.11 [0.91 to 1.35] | 1.28 [0.97 to 1.68] | |

| Dieters | 1.2 [0.76 to 1.88] | 1 [Ref] | 1.17 [0.91 to 1.51] | |

| Disordered Eating |

1.08 [0.65 to 1.78] | 0.97 [0.65 to 1.45] | 1 [Ref] | |

| Suicide Attempt | ||||

| EAT-III | ||||

| EAT-I | Asymptomatic | Dieting | Disordered Eating | |

| Asymptomatic | 1 [Ref] | 0.99 [0.76 to 1.28] | 1.19 [0.87 to 1.62] | |

| Dieters | 1.09 [0.81 to 1.48] | 1 [Ref] | 0.83 [0.6 to 1.15] | |

| Disordered Eating |

0.87 [0.62 to 1.23] | 0.98 [0.74 to 1.29] | 1 [Ref] | |

|

Weight Teasing by Peers |

||||

| EAT-III | ||||

| EAT-I | Asymptomatic | Dieting | Disordered Eating | |

| Asymptomatic | 1 [Ref] | 0.92 [0.74 to 1.14] | 0.95 [0.68 to 1.32] | |

| Dieters | 0.97 [0.64 to 1.47] | 1 [Ref] | 1.21 [0.94 to 1.56] | |

| Disordered Eating |

0.63 [0.37 to 1.08] | 0.91 [0.63 to 1.3] | 1 [Ref] | |

|

Family Weight Teasing |

||||

| EAT-III | ||||

| EAT-I | Asymptomatic | Dieting | Disordered Eating | |

| Asymptomatic | 1 [Ref] | 0.87 [0.69 to 1.1] | 1.38 [1 to 1.89] | |

| Dieters | 1.1 [0.74 to 1.62] | 1 [Ref] | 1.16 [0.91 to 1.47] | |

| Disordered Eating |

0.63 [0.38 to 1.05] | 1.01 [0.69 to 1.47] | 1 [Ref] | |

|

Family Communication/Car ing |

||||

| EAT-III | ||||

| EAT-I | Asymptomatic | Dieting | Disordered Eating | |

| Asymptomatic | 1 [Ref] | 0.92 [0.76 to 1.11] | 0.66 [0.5 to 0.87]*** |

|

| Dieters | 0.59 [0.39 to 0.88]*** |

1 [Ref] | 1.05 [0.79 to 1.4] | |

| Disordered Eating |

1.05 [0.6 to 1.83] | 0.8 [0.51 to 1.24] | 1 [Ref] | |

|

Family Meal Frequency |

||||

| EAT-III | ||||

| EAT-I | Asymptomatic | Dieting | Disordered Eating | |

| Asymptomatic | 1 [Ref] | 1.2 [0.99 to 1.46] | 0.95 [0.73 to 1.24] | |

| Dieters | 1.04 [0.67 to 1.61] |

1 [Ref] | 0.82 [0.64 to 1.06] | |

| Disordered Eating |

1.03 [0.61 to 1.73] |

0.92 [0.55 to 1.54] | 1 [Ref] | |

| Gender**** | ||||

| EAT-III | ||||

| EAT-I | Asymptomatic | Dieting | Disordered Eating | |

| Asymptomatic | 1 [Ref] | 3.2 [2.16 to 4.61***] |

4.7 [2.57 to 8.67]*** | |

| Dieters | 0.8 [0.28 to 2.32] | 1 [Ref] | 1 [0.46 to 2.2] | |

| Disordered Eating |

0.3 [0.06 to 1.17] | 1.7 [0.41 to 6.7] | 1 [Ref] | |

Unit for all Odds Ratios is 1 standard deviation except for Gender which compares Girls to Boys (Reference Group);

Model for BMI did not converge;

p < 0.05;

Model for gender is adjusted for age, SES and race

Gender was also a significant predictor of the transition between latent groups. Female respondents showed greater odds of transitioning to a more symptomatic group at 10-year follow-up than male respondents: females had (a) a three times greater odds (OR = 3.20, 95% CI 2.16–4.61) of transitioning from the asymptomatic group to the dieting group and (b) a four times greater odds (OR = 4.70, 95% CI 2.57–8.67) of transitioning from the asymptomatic group to the disordered eating group than males.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to empirically derive ED symptom groups and examine both (a) the stability of and transition between those groups within a community adolescent sample over 10 years and (b) the associated risk factors for transition. Three groups of ED symptoms (asymptomatic, dieting, and disordered eating) were identified; further, while there was a high probability of stable ED group membership over 10 years (particularly for those in the asymptomatic and dieting groups), there was also a notable probability of transitioning to a different group. Transitions between groups could be predicted by particular psychological and socio-environmental risk factors present in adolescence.

Many adolescents begin or continue to struggle with disordered eating through early adulthood. There was a 40% chance that individuals, particularly females, who were asymptomatic at baseline would transition to one of the two symptomatic groups by adulthood. This finding is consistent with prior work from Project EAT, which found that one-third of asymptomatic adolescents became symptomatic five years later (8). Findings also suggest that once ED behaviors begin, they are very difficult to stop, which is also consistent with prior work which followed adolescents for four years (14). Unfortunately, we found that there was a 75% chance that those with more severe pathology during adolescence (e.g., disordered eating group) would continue to belong to the disordered eating group or transition to the dieting group over the 10-year follow-up. This finding is striking, highlighting early ED symptoms as risk factors for continued ED behaviors (e.g., 34,35) and the importance of early prevention and intervention effects (36).

Despite adolescence and young adulthood being a significant developmental time period for ED symptom onset and maintenance (34,35), the current findings suggest several positive and promising outcomes. First, consistent with prior studies (13,14) most participants had membership in the asymptomatic group at both time points. Second, if adolescents belonged to the asymptomatic group at baseline, they were most likely to continue to belong to that group 10 years later. Third, if adolescents engaged in severe ED behaviors (e.g., disordered eating group), there appeared about a 25% chance that they would be asymptomatic by young adulthood, suggesting that a notable portion of adolescents with disordered eating do, indeed, get better. It remains unknown, however, whether individuals improved on their own, as a result of treatment, or perhaps a combination of the two.

Substance use, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms were found to be meaningful predictors of symptom group transition. Contrary to Kansi and colleagues (13), which reported null longitudinal findings, we found that the lower one’s self-esteem in adolescence, the more likely one was to transition to a more severe symptom group over time. In this way, higher self-esteem appears to be a protective factor. Depressive symptoms and substance use, on the other hand, appear to be risk factors for transitioning or remaining in a more severe ED group over time. Similarly, the same was found to be true for the socio-environmental risk factor of family weight teasing, which approached statistical significance. It appears that family weight teasing is more influential and powerful to an adolescent than peer weight teasing, as this was not a significant risk factor. Thus, one possibility is that individuals are at particular risk for disordered eating in early adulthood if family teased them about their weight and they experienced depressive symptoms during adolescence. It may be the case that individuals engage in disordered eating in an effort to cope, or perhaps to improve their mood or alleviate their negative affect (e.g., 37), which may result from weight teasing. Another interpretation is that individuals are at risk to engage in disordered eating if they are already engaging in other risky behaviors, like substance use.

In examining risk factors for transitioning between groups, we found little evidence that any of the variables predicted whether someone remained stable in the disordered eating group or transitioned out to the asymptomatic group. The contradictory findings relating family communication/caring to group transition in both directions provide unclear interpretations. However, we do know that this transition and stability occurs and we recommend that future research aim to identify factors that are associated with stability in a more severe ED group. Moreover, despite the other risk factors having prior evidence in the field, they do not appear to be important for symptom group transition in this longitudinal sample, including body dissatisfaction. This may be a result of assessment methodology or perhaps those factors are more relevant for symptom onset and less relevant for symptom transition. Further research is needed to clarify this.

These findings have important clinical implications. Many individuals endorse ED symptoms during adolescence and continue to throughout the transition into early adulthood. This high prevalence stresses the importance of early detection and intervention for ED symptoms, particularly among young girls. Along these lines, our results also indicate the importance of regular screening for a broader range of psychological and socio-environmental variables. A significant likelihood of transitioning from one symptom group to another was predicted by four key variables (low self-esteem, depressive symptoms, substance use, and family communication/caring), thus underscoring the importance of attending to the individual’s psychological and socio-environmental context as well as multiple risky behaviors. For best care practices, healthcare and school-based professionals should inquire about a broad range of behavioral and emotional concerns. One possibility is that these screenings can lead to referrals for group skills training and/or therapy services to address individuals’ more specific problems. Of course, these interventions are likely to take time.

This study has notable strengths, including its large, diverse community sample, the inclusion of males and females, the longitudinal 10-year design, and the identification of empirically-derived ED symptom groups to build upon prior work to enhance the field’s understanding of the transition of ED symptoms. However, there are also limitations. First, we relied on self-report questionnaires to assess risk factors and behaviors in our sample. Thus, it is not known if we would have found different results by including interviews that may have provided more in-depth information. For example, the item used to assess self-weighing did not assess specific frequencies of self-weighing; thus “I weigh myself often” may have been interpreted differently by individuals. Second, despite the fact that we used the same indicator items as Ackard and colleagues (8), we employed LTA, which empirically identifies groups, and as a result, we identified different groups than those pre-determined by Ackard and colleagues (8). Future work on diagnostic or symptom transitions would benefit from including individuals at early ages such as pre-adolescence, as well as including broader psychological, familial, and environmental factors, to clarify factors contributing to the onset and transition of symptoms over time and by gender. Third, this study utilized two assessment point over a 10-year period and thus cannot determine the timing of symptom onset and transition, including identification of remission and relapse. Future studies may benefit from including multiple data points. Fourth, some of the test-retest scores for EAT-I were low for some ED symptom indicators, which may be of a result of (a) higher impulsivity and thus greater variability in behaviors during adolescence and/or (b) a selection bias for more reliable, consistent respondents by EAT III due to participant drop out over the 10-year follow up.

In conclusion, using LTA, we empirically-derived distinct ED symptom groups in a sample of community adolescents and found that the stability of symptom groups appeared to be more common among the asymptomatic and dieting groups than the disordered eating group. Some of the transitions from one group to another across time could be attributed to one or more of four significant predictors: low self-esteem, depressive symptoms, substance use, family communication/caring.

Acknowledgments

Development of this paper was supported, in part by National Institute of Health grants T32MH082761 and 1R01HL084064-01A2.

Footnotes

Readers are referred to Neumark-Sztainer and colleagues (6) for more information on attrition and weighting.

Survey measures were pilot tested at before administration of both EAT-I and EAT-III. Test-retest reliabilities for items from EAT-I and EAT-III that did not change substantially after pilot testing are reported.

All variables used to predict transition between latent categories were measured at EAT-I.

All authors have declared that there are no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Goldschmidt AB, Wall MM, Zhang J, Loth KA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Overeating and binge eating in emerging adulthood: 10-year stability and risk factors. Dev Psychol. 2016;52:475–483. doi: 10.1037/dev0000086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Combs JL, Pearson CM, Zapolski TC, Smith GaT. Preadolescent disordered eating predicts subsequent eating dysfunction. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38:41–49. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Croll J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Ireland M. Prevalence and risk and protective factors related to disordered eating behaviors among adolescents: Relationship to gender and ethnicity. J Adolesc Heath. 2002;31:166–175. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Story M, et al. Dieting and unhealthy weight control behaviors during adolescence: Associations with 10-year changes in body mass index. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med. 2012;50:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stice E, Marti CN, Rohde P. Prevalence, incidence, impairment, and course of the proposed DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses in an 8-year prospective community study of young women. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:445–457. doi: 10.1037/a0030679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Larson NI, Eisenberg ME, Loth K. Dieting and disordered eating behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:1004–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eddy KT, Dorer DJ, Franko DI, Tahilani K, Thompson-Brenner H, Herzog DB. Diagnostic crossover in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: Implications for DSM-V. Am J Psychiat. 2008;165:245–250. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07060951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ackard DM, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Stability of eating disorder diagnostic classifications in adolescents: Five-year longitudinal findings from a population-based study. Eating Disorders. 2011;19:308–322. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2011.584804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldschmidt AB, Wall MM, Loth KA, Bucchianeri MM, Neumark-Sztainer D. The course of binge eating from adolescence to young adulthood. Health Psychol. 2014;33:457–460. doi: 10.1037/a0033508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Dempfle A, Konrad K, Klasen F, Ravens-Sieberer U. Bella study group. Eating disorder symptoms do not just disappear: the implications of adolescent eating-disordered behavior for body weight and mental health in young adulthood. Eur Child Adoles Psy. 2014;24:675–684. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0610-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen KL, Byrne SM, Oddy WH, Crosby RD. Early onset binge eating and purging eating disorders: course and outcome in a population-based study of adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psych. 2013;41:1083–1096. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9747-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wonderlich SA, Joiner TE, Keel PK, Williamson DA, Crosby RD. Eating disorder diagnoses: empirical approaches to classification. Am Psychol. 2007;62:167–180. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kansi J, Wichstrom L, Bergman LR. Eating problems and their risk factors: A 7-year longitudinal study of a population sample of Norwegian adolescent girls. J Youth Adolescence. 2005;34:521–531. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Micali N, Horton NJ, Crosby RD, Swanson SA, Sonneville KR, Solmi F, Calzo JP, Eddy KT, Field AE. Eating disorder behaviours amongst adolescents: investigating classification, persistence and prospective associations with adverse outcomes using latent class models. Eur Child Adoles Psy. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00787-016-0877-7. online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cain AS, Epler AJ, Steinley D, Sher KJ. Concerns related to eating, weight, and shape: Typologies and transitions in men during the college years. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:768–775. doi: 10.1002/eat.20945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cain AS, Epler AJ, STeinley D, Sher KJ. Stability and change in patterns of concerns related to eating, weight, and shape in young adult women: a latent transition analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010;119:255–267. doi: 10.1037/a0018117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobi C, Hayward C, de Zwaan M, et al. Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: Application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:19–65. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stice E. Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2002;128:825–848. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pacanowski CR, Linde JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Self-weighing: Helpful or harmful for psychological well-being? A review of the literature. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4:65–72. doi: 10.1007/s13679-015-0142-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rohde P, Stice E, Marti CN. Development and predictive effects of eating disorder risk factors during adolescence: implications for prevention efforts. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48:187–198. doi: 10.1002/eat.22270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearson CM, Wonderlich SA, Smith GT. A risk and maintenance model for bulimia nervosa: From impulsive action to compulsive behavior. Psychol Rev. 2015;122:516–535. doi: 10.1037/a0039268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bodell LP, Joiner TE, Keel PK. Comorbidity-independent risk for suicidality increases with bulimia nervosa but not with anorexia nervosa. J Psychiat Res. 2013;47:617–621. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haines J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Eisenberg ME, Hannan PJ. Weight teasing and disordered eating behaviors in adolescents: Longitudinal findings from Project EAT (Eating Among Teens) Pediatrics. 2006;117:e209–e215. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neumark-Sztainer D, Eisenberg ME, Fulkerson JA, Story M, Larson NI. Family meals and disordered eating in adolescents: Longitudinal findings from Project EAT. Arch Ped Adol Med. 2008;162:17–22. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ackard DM, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Prevalence and utility of DSM-IV eating disorder diagnostic criteria among youth. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:409–417. doi: 10.1002/eat.20389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders—text revised. 4th. Washington, D. C: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Must A, Dallal GE, Dietz WH. Reference data for obesity: 85th and 95th percentiles of body mass index (wt/ht2)—a correction. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:773. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.4.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kandel DB, Davies M. Epidemiology of depressive mood in adolescents: An empirical study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:1205–1212. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290100065011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Perry C. Parent-child connectedness and behavioral and emotional health among adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Story M, Fulkerson JA. Are family meal patterns associated with disordered eating behaviors among adolescents? J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:350–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sherwood NE, Wall M, Neumark-Sztainer D, et al. Effect of socioeconomic status on weight change patterns in adolescents. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6:A19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis with applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. Hoboken NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Killen JD, Taylor CB, Hayward C, Wilson DM, Haydel F, Hammer LD, et al. Pursuit of thinness and onset of eating disorder symptoms in a community sample of adolescent girls: a three-year prospective analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16:227–238. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199411)16:3<227::aid-eat2260160303>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kotler LA, Cohen P, Davies M, Pine DS, Walsh BT. Longitudinal relationships between childhood adolescent and adult eating disorders. J Am Acad Child Psy. 2001;40:1434–1440. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200112000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker HD, Joyce T, French E, Willan V, Kane RT, Tanner-Smith EE, McCormack J, Dawkins H, Hoiles KJ, Egan SJ. Prevention of eating disorders: A systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. 2016;49:833–862. doi: 10.1002/eat.22577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polivy J, Herman CP. Dieting and bingeing: A causal analysis. Am Psychol. 1985;40:193–201. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.40.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]